7,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

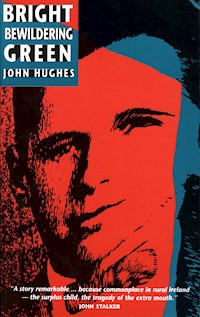

Bright Bewildering Green is a vivid, harrowing tale – told from the emotional security of middle age – of an impoverished childhood in rural Northern Ireland during the 1950s and early '60s. In its detailed evocation of the realities of life for an orphan family on an Armagh hill-farm, the sentimentality of the family pig is bled to death. William vents his frustrations on John, his sensitive youngest brother, and severe beatings lead to the boy's collapse and treatment for epilepsy until he escapes to Coventry. Inherited pluck and fortitude sustain him in a strange city, and from an achieved tranquillity the author allows himself to reflect upon the horrors, and occasional joys, endured as a child and faces them with dispassion. This compelling narrative is the record of a survivor.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 1990

Ähnliche

JOHN HUGHES

BRIGHT BEWILDERING GREEN

WITH A FOREWORD BY JOHN STALKER

THE LILLIPUT PRESS

1991

To Susy Hugheswhose gentle bullying awoke my inner self

I saw the sunlit vale, and the pastoral fairy-tale;

The sweet and bitter scent of the may drifted by;

And never have I seen such a bright bewildering green,

But it looked like a lie,

Like a kindly meant lie.

When gods are in dispute, one a Sidney, one a, brute,

It would seem that human sense might not know, might notspy;

But though nature smile and feign where foul play has stabbedand slain,

There’s a witness, an eye,

Nor will charms blind that eye.

(Edmund Blunden, ‘The Sunlit Vale’)

Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Foreword

Preface

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Copyright

Foreword

I first met John Hughes a dozen or so years ago on a bitterly cold February night. I watched him drive, for no discernible reason, twice round a Coventry roundabout followed too closely by a pair of suspicious policemen whose car skidded on the ice and crashed into his. During the next few minutes I witnessed the art of the gifted salesman as John Hughes persuaded the policemen they were entirely in the wrong but out of respect for them he would take the matter no further. I hold precious the memory of two apologetic policemen loading bits of their patrol car into the back seat and clattering away into the night. It was then I decided John Hughes was an interesting man.

Out of that meeting has grown a friendship based, I suppose, on the attraction of opposites. When it began I was a senior detective officer in a high profile public job, he a retail businessman worrying about interest rates and cash flow. We disagreed about many things; for example his political thoughts are not always mine and his total (and declared) disinterest in my sporting loves of athletics and Manchester United are usually matched by my numb response towards his preferred pastimes of weight-lifting and competitive clay-pigeon shooting. Yet our differences have been the catalyst for our friendship: the antidote to the stresses of our respective jobs. In recent years life for both of us has moved dramatically on: I am no longer a policeman and John Hughes’s restless spirit has turned its energies in other business directions. Much has changed.

But, despite the closeness of our enduring friendship, I have always known I did not really know him. Not that he is a secretive man; indeed with people he likes and trusts he is often vulnerably open, but he was unfailingly uncomfortable with discussions about childhood influences or why people turn out the way they do. Over-curiosity about his early life was deflected by a directness close to rudeness. The John Hughes I have known since 1978 has been a man of here and now and like the rest of his friends I learned to understand that whatever the past contained it belonged to a different John Hughes, the shadow of whom we were unlikely ever to see.

But in this book that shadow becomes substance and at the end of it the child he was holds the hand of the man he became. Like many before him, John Hughes has found that a peaceful mind demands that the demons of the past be faced, and one way of doing it is to fight them with a pen in your hand. He confided in me a year or so ago that he had begun writing and I promised him that I would write a foreword if his efforts were considered good enough for commercial publication.

Bright Bewildering Green is the result. A story remarkable not because it is unusual but because it was – and still is – commonplace in rural Ireland: the story of the surplus child, the tragedy of the extra mouth. He has written a first-hand account of family resentment and cruelty, and of countervailing affection and hope leading him to a successful new life.

The book will surprise many people who know the author. I confess that the quality of the writing surprises me, from a man who cheerfully admits to having read only a couple of books in his life. But when did human talent not have the element of surprise? And since when was the writing of a readable book the preserve of educated men?

Bright Bewildering Green is a simple story told by the man to whom it happened. I am glad to have read it.

John Stalker

Manchester, January 1991

Preface

When I began to write this book I worried constantly about the pain and embarrassment it might cause my family. Gradually my anxieties receded as several powerful reasons to continue took command. First, I had to exorcize the ghost of my childhood which had haunted me for over twenty years. Secondly, I believed the story should be told, if only to try and reach those who suffer as I did. Finally, if I did not tell the story no one else would, and a chance for the voice of an ordinary man to be heard would have been lost yet again. Death strikes early in my family: mother died at forty-five and both father and William, my eldest brother, at forty-eight. So I decided to crack on.

I was unaware of the obliteration that had taken place until I tried to remember basic details of my family history. With the patient help of a London genealogist and my cousin Joseph Hughes, I eventually pieced together a picture of my fragmented background.

In 1984 I sought help from a hypnotherapist because although I had become skilled at clay-pigeon shooting, the winning of championships repeatedly eluded me, often prompting nervous attacks that shattered my confidence.

After weeks of counselling, the therapist asked if I was prepared to talk about my childhood. Reluctantly I agreed when he said that the root of the problem lay in my early life and that he could only help if I talked it through with him. I told him about the violence, my diagnosis of epilepsy at the age of fourteen and the years on medication. He asked me how long I had taken Mysoline tablets for and when I replied that I had given them up after five years although the medical reports had recommended seven, his obvious relief concerned me. He explained that Mysoline was still one of, Britain’s major tranquillizers which could have horrendous long-term effects and that I was lucky to still be in possession of my senses and not reduced to a mindless wanderer. He seemed intrigued by what he called my amazing constitution until I reminded him of why I was there. He told me that my problem was easily diagnosed, that I had a victory phobia. Because I had been told as a youngster that I was hopeless, in moments of extreme pressure I still believed it.

I followed his course of relaxation therapy and in 1985 represented England in the Home Counties International Sporting Clay Pigeon Championship, hosted in Ireland. Being an Irishman going home to shoot for England gave me a strange feeling of revenge that I did not enjoy.

I gave no more thought to my supposed childhood illness until the writing of this book when, in a quest for the truth, I confronted my own doctor. He read out a letter from the doctors in Ireland written twenty-five years earlier, which stated: ‘The results of the EEG are mildly unstable for age. This is not symptomatic with epilepsy but we have decided to treat it as such and suggest that you continue to do so.’

My doctor, who had recently taken over the practice, felt that it was unlikely I was ever an epileptic and added that nowadays the treatment I received would be highly controversial. When I asked him to read out another letter from my file he was perplexed and asked how I knew such a letter existed. I confessed that ten years earlier I had been left alone in the surgery for a moment and stole a look at my file. My furtive reading was short-lived, but I had managed to glean the opening sentence.

‘This poor wee lad who has suffered much trauma and violence …’

The letter was missing. I left the surgery disappointed that I could not pursue the matter and my suspicion that something was wrong grew deeper.

When I discovered that a law passed in 1988 gave me the right to inspect my records my doctor was most helpful and reopened the files. All that existed of the EEG report was a three-line extract stating:

‘There were no epileptic waves found, or focus seen.’

None of the correspondence bore a signature, nor the name of the hospital or consultant concerned. Though my doctor assumed that the reports had been reduced to make filing easier, I found this hard to accept because other bulky reports were still intact. All references to the first doctor I had attended in Coventry, who in 1962 had obtained my files from Ireland, were also missing. Determined to obtain my full medical records, I made a series of phone calls to hospitals in Belfast and eventually my completed file proved that I was not and never had been epileptic.

However, I still wonder why I was prescribed Mysoline for seven years with no supervision or subsequent tests to monitor the effect such a tranquillizer was having. I have recently learned that Mysoline is no longer used except in the treatment of epileptic dogs.

I scrutinized the family details I had compiled, a fumble of documents with beautiful-sounding addresses that concentrated my mind’s eye. It was with these rummagings and a relentless compulsion to face the past that I decided to return home again. The knowledge that my wife was to accompany me on the week’s holiday eased my anxieties. What saddened me most was that it was only because of William’s death that I was able to go.

In 1986, after twenty-three years of self-enforced exile, I had returned to County Armagh to make peace with William on his deathbed. Duty done, I had left immediately, the ghosts of my past still too powerful to withstand.

On the plane I had eaten a small Ulster breakfast as if in preparation for my return to this lovely country now synonymous with death and violence. Anxiety wrapped itself around me like too tight a vest. What would it be like? Would I be accepted? I thought of the area so well known to me in childhood: Markethill, Newry, Portadown, Tandragee, Keady, Crossmaglen and Armagh City. Flashes of TV news depicting devastation darted through my mind, reminding me of events during my long absence. How could it all have happened? How had the lush serene country of my childhood become one of the most dangerous places in the world? Most people associate the present troubles with 1969. However, as I mulled over the pages of my mental photo album, an uneasy dawning provoked questions which until now I had conveniently pushed aside. Were the battle-lines drawn during my childhood, placed there carefully like fillets of cement set to withstand future pressures? In my own town of Markethill I remembered the police with guns and the sandbagged barracks. Within the community, fear of an IRA attack was muted, occasionally changing angrily to the ‘stupid bastards’ when bridges were blown up, blocking lonely country roads.

I remembered the heavily black-clad figure of William, huddled with other B Specials at windy crossroads, when one week after he was transferred from a distant brigade to the convenience of our own townland his old comrades shot dead a man in a car who failed to stop after being signalled to do so. There was my father’s disgust at the RUC having to fight battles against men who shot at them from behind hedges two fields away. And the first few lines of a lengthy poem from a book kept in our hall-stand:

Shall time erase the memory of the ragmen mean andrough,

Who sought to face our special boys at the school ofMulladuff?

I thought of the rural disparities and pressures. Not so evident then, they now seemed as stark as the bloody pictures of Christ nailed to the cross.

Religion was fed to us like hot stews to make us grow, and, commandeered into the Orange Order, we were made to beat triangles, play accordions, and learn the ‘Sash’, the most famous of all Protestant marching songs.

The jealous guarding of lands that had been in families for generations promoted scorn for those who released territory. I reflected too on the long fierce legal battle with William for my share of the farms.

These memories stormed about my head and I countered the rush with comforting thoughts of home and my reasons for being here.

‘Make your peace, say goodbye, and get back on the plane.’

A ginger-haired freckled man, built like a bullock, squeezed himself into the taxi and drove off towards Portadown. The sky was damp, the roads deserted. He didn’t talk much and it suited me. Anxiety had left and fear was encroaching. Why could I not be like father or my brother Joe? They were fearless men. I must have inherited my mother’s genes. She was shy and timid, and momentarily I hated her.

Already I was clinging to the slippery sides of a tunnel that sucked me back to childhood.

‘Come on, come with us, you’re ours again, you didn’t think we would let you get away, did you?’ whispered a voice in my head.

High on a hill, Craigavon Hospital with its glare of windows sat elevated like a half-way heaven. I had spoken to my sister Molly before leaving England so they were expecting me. At reception, a kind-looking woman asked,

‘Are you the brother from England?’

‘Yes, I am.’

Well, it’s a long way up, take the lift and go to the end of the corridor.’

My breathing was erratic. In a room on the right I saw a huddle of people sitting splay-legged on vinyl seats. At the back two stern-faced young men looked uncomfortable wrapped in outsized green clothes. They stood up quickly, hands concealed, when I came in, then sat down again. My cousin John moved forward and shook my hand.

‘How are you, boy?’ he asked.

To his left a middle-aged stocky man with thinning black hair and a surprised look nodded and made to stand up.

‘William’s in there, John,’ said my cousin, pointing to an open door.

The room was untidily packed with people I didn’t know apart from Violet, the sister I had missed so much. Her black wavy hair had been cut short to her ears. Her small hands were red and chapped.

‘John, hello, this is terrible, isn’t it?’

I nodded.

‘It’s good of you to come,’ she said.

William lay hunched on a table. He was much bigger than I expected.

‘He took a turn yesterday,’ whispered Violet. They brought him here and now he has gone into a coma – the doctor says it’s a tumour on the brain.’

Beneath the window three brow-furrowed women, arms folded, sat on guard. None of them fitted my faint memory of William’s slim wife. Scanning them, I asked, ‘Which one of you is Sally?’

‘I am,’ said a sad-faced plump woman.

‘Molly not here, Violet?’ I asked in a rough voice.

‘No, she’ll be along later, but have you seen Joe?’ she asked, rescuing me from an awkward silence.

Back in the waiting-room I was embarrassed at not recognizing the black-haired man who had earlier made to stand up. It was my other brother.

‘Hello, Joe, I thought it was you,’ I said shakily.

‘Well, I would have known yourself anywhere, John,’ and he offered me his seat. After some nervous exchanges, I asked him to introduce me to the bulky green-clad men.

‘Ah sure, these boys are not with us, they’re just waiting,’ he said with surprise.

I later learned that they were armed police guarding an RUC officer who had been shot that morning and was lying in the room next to William.

After lunch I walked aimlessly around the corridors with Violet. My other sister Molly still had not arrived. When Violet left I made my way back to the ward. William’s shoulder felt cold and clammy as I whispered ‘I forgive you.’ He shuddered and snorted, and I felt the words had reached him. Now with his life slowly slipping away, he too forgave. Peace had touched us both, but why did it have to be like this? A current of emotion shook my body – the childhood I had sentenced to dark imprisonment burst back into my brain but my resolve stiffened and I waved a sweeping goodbye to the sea of faces.

Next morning, on the way to the airport, I stopped at the parish church, its squat granite walls as imposing as ever. I walked quietly along a stone path to the graveyard and found the identification plate that had leaned there since 1959. The number 44 barely visible through the rust projected a force so strong it seemed to engulf me. The anonymity of my parents’ grave wounded me. Here in a beautiful holy acre of Ireland I saw and felt ugliness.

Two years later, I planned my second return. What would I tell them? They must have known that I parted company earlier with Uncle Joe and lived briefly with Aunt Minnie, father’s sister. I would tell them about the lonely years spent in miserable flats, the hunger, the search for security and identity, and the craving for love and affection. I would tell them about my desire to be alone at Christmas despite the occasional invitation to join a family. Of course I would tell them about the struggle for work, my yearning to be accepted as part of society and to achieve total financial independence. I would explain how at twenty I fought off a nervous breakdown, that my wish to become a boxer was halted by the result of another EEG. I would tell them that as I grew older I found opportunities which rewarded my efforts with recognition and stability. I would tell them about my lovely home.

When the time came I said none of these things, my preparatory thoughts were washed away with the warmest welcome I had ever received. Of the seven days spent, five were taken up visiting relatives and friends. They offered us their best chairs, stuffed us with food and begged us to come back. My brother and sisters regarded me with mannerly interest while I scanned them for signs of semblance. Sadly I saw none. I do not think the passage of time had altered them significantly. It was I who had changed, so much so that as I reflected on the lad of Seaboughan Lane, driving home the cows, it was like seeing a mirage.

I found it strange that most people did not mention William other than to say that he had gone home early. I asked my family why, in their opinion, he had beaten me. They didn’t seem to know and in quiet moments apologized for what had happened, stressing that they had been unaware it was so serious. For many years I had harboured bitterness towards William for the violence he had inflicted but now I could see it differently. He beat me because of his own frustrations, for a youth lost, plundered by pressure and a responsibility he was unable to bear.

At Glassdrummond Church I gazed at the headstone I had had erected over my parents’ grave before filing into the pew to listen to a service that had not changed in twenty-five years.

Reunion with Patsy Goodfellow, my closest childhood friend, was a celebration of a bond of love which time had not eroded. We embraced each other and with my cousin John Hunter spent many hours laughing and reliving a way of life now vanished.

Our farmhouse at Lisnagat lay derelict, a grey ghostly aura shrouding the disfigured main dwelling. A faded curtain flapped through a broken window. The few out-buildings that had not crumbled into heaps of stone were now owned by a neighbouring farmer. The people I spoke to were upset that the fields had gradually been sold off thus landlocking the house, but as I walked through its chilly atmosphere I felt it was what the house wanted. To be left alone forever.

One

I was born on 18 May 1947, the youngest of five children. Our home was near Markethill in County Armagh, a town built not so much on a hill as on a slope. At the bottom of its wide street lay J. D. Hunter’s, a general store selling everything from groceries to animal food. Father dealt here, paying the bill on an agreed once-a-year basis. The livestock sales yard next door was a favourite haunt of my brother Joe, who wanted to become an auctioneer. I am sure he would have been suited to the exciting rich language they used to whip up interest in a cow with the worse dose of skitter ever seen.

Opposite the yard, the chemist’s roman numeral clock above the door made it the most looked-at shop in the town. Our favourite shop, Boyce’s, was in Newry Street, a short walk from the main thoroughfare. Santa must have bought all his sweets there. Gob-stoppers, lollipops, toffees and large untouchable jars crammed with temptation floated colourfully before us through the small window. Old Mrs Boyce used to scrape the bottom of the jars with bony fingers.

‘And I’ll have a pennyworth of these and twopence worth of those. How much are these ones? No, I’ll have them ones.’

‘Now, you’re having these, John Hughes, and that’s it. You’ve been here for ten minutes,’ she’d say.

Back in Main Street the two public houses opposite each other were owned by the Robinson brothers, Louis and Tommy. Years earlier they had quarrelled and still did not speak. Louis was also the local undertaker and word had it that he knew his customers so well that rarely did he have to measure them for their last journey.

At the top of the street, opposite the ever-popular Morgan’s Bar, was Jimmy Dixon’s barber’s shop with its red and white pole outside. If Jimmy was not in his salon we would just wait at the door knowing that he would soon spot us. He’d come tearing across from Morgan’s Bar, push his brown horn-rimmed glasses high up on the bridge of his nose, button the white coat and explain, ‘Right, boy, I’ve just been to see a man about a dog. Usual style, is it?’

The question was irrelevant. Jimmy was inflicted with scissoritis so there was only one style – fast and furious. If he’d been to see too many men about too many dogs then it was just furious. As with all the traders in town he liked my father and sometimes slipped me a drop of Silvikrin hair oil. I hated having my hair cut.

‘It’s too cold for a haircut, Da,’ I’d moan.

‘You’re having a clip or I’ll graze you with the sheep. Come on,’ and grabbing my elbow he’d steer me in. Hunched like a frightened rabbit I’d endure twenty minutes of incessant snipping. Though Jimmy might pause to greet a customer, the scissors would continue their rhythm around my ears.

‘Who’s a good-looking lad, then?’ father would say when the job was complete.

‘He is that, Willie, but keep him covered up for a few days, he might be catchin’ cold without all that wool around his ears!’

On the Keady Road out of Markethill lay a small cottage surrounded by black painted sheds and a lovely garden. George Gardner the postman lived here. My father claimed that he was the result of a visit by the Black and Tans to our area and insisted he would look better in a Glengarry than in the old black cap he always wore. Leaning from side to side, with a big brown sack on his back, George’s lumbering legs generated just enough power on his ancient bicycle to propel him to the farmhouses along his delivery route.

‘Cuckoo – cuckoo – cuckoo.’

The sound echoed for miles and everyone knew that George, the man with a hundred clocks in his house, was on his way.

But thirty-five years ago I cared for nothing, beyond the maze of white gravelled roads that led me past farms and cottages, up hills and through peaceful countryside, where cud-chewing Friesians in rolled-back fields clambered up green clumped banks to gaze at me. In blustery showers I would shelter under trees or walk tight against thick hedgerows, shielding my face with a rain-soaked leather satchel. Our home farm in Lisnagat, a rambling old place formerly known as Lisnagat House, had about fifty acres of arable and grazing land. It was approached through a long bumpy lane skirted with hedges and ferns. The house overlooked a bedded stone yard with steps leading down to a sunken terrace and a whitewashed scullery beyond. Cool and airy in the height of summer, it stored our foodstuffs.

Being three miles from Markethill, the farm had no gas or electricity, but the pale moonstone light of the tilley-lamp glowed with a special beauty. It was an art to keep hurricane-lamps alight as we scurried across the windy yard to comfort a calving cow.

There was no indoor lavatory, and if one of the two chamber-pots could not be found, then groping our way down the stairs, along the hallway, and out into the cold rat-infested yard, taught effective bladder control at night.

We grew oats, barley and hay, with potatoes, turnips and other vegetables for our own consumption. The six-hundred-odd poultry, hundred pigs, sixteen sows, herd of white Herefords and seventeen milking cows depleted the food-stocks and kept us hard at it.

My father was both clever and resourceful, building the byres, piggeries, dairy-house and huge hayshed himself. He could mend and make all manner of farm implements and had, as a young man, built a milk cart for his father. He devised a drinking system for the cows by erecting a tall concrete structure around the well. A ladder led to a wooden platform supporting a large tank at the top. From the dark hole the water was pumped up by a diesel generator, through pipes to the cows’ drinking bowls. The cows soon learned to activate the supply by pressing their noses against the flanges. None of these skills had been taught. My father studied the problem, decided on a solution, then set about making it work, and it usually did.

Our second farm, called McCune’s after its previous owner, was two miles away. Wild overgrown hedges and trees shaded the lonely entrance where the wind was always in conflict with itself, and only the occasional rasp of a corncrake invaded its seclusion. Cattle were sometimes grazed here, and a rusting corrugated metal lean-to provided shelter on rainy days and some protection from tortuous clegs in blistering heat. A five-bar gate opened onto a part-cobbled yard that even sure-footed bullocks were wary of crossing. The house was a grey crumbling ruin flecked with whitewash. The only habitable room served as my grandparents’ home. I remember seeing the old woman dressed in black, stick in one hand and a bucket in the other, negotiate her way to the tiny well at the end of the yard. I had visited them once with my father, leaping down from the tractor to chase a three-legged rat. Then, peering into their room, I saw a few sticks of furniture, a mattress on the floor, some bales of hay and bread and jam on a well-scrubbed rough-hewn table.

One day the old lady hobbled the two miles to our house. She said she felt tired, so father told her to go upstairs and lie down. She lay for a week until she died, and I cried every night because she was in my bed. Grandad, who considered himself something of a lay preacher, visited us every month afterwards. ‘Don’t lose it,’ he would say, pressing bright shillings into our hands. I was sad when he died but pleased with the day off school.

Except for a few early Christmases when father was alive, festive occasions passed us by. One day my sisters announced that I would be six tomorrow and that was enough for me. I stood in the front field surrounded by a rush of buttercups, a gende breeze rocking the sally trees and the apple blossom in the orchard all fluffed up in powdery pinkness. I did not expect presents, but to my surprise Violet gave me a bagful of soft toffees. She rubbed my hair and told me I was a big boy now.

Chewing my last toffee, I watched the cows meander in after milking to graze the long grass. Father had warned me not to trust old Nancy, but I liked her and watched her waddling towards me; slowly at first, then suddenly breaking into a trot, she lowered her head, put her horns down and charged. I panicked and fled. ‘Roll, John, roll,’ I heard as I tripped and fell. I rolled and thudded into father’s feet. There was a sharp crack and Nancy halted, stunned by the blow from his pitchfork. For a few seconds she snorted in defiance, then eyes rolling, tail swishing, she tramped angrily away swinging her head.

‘I told you to mind her,’ growled father.