Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Pocket Essentials

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

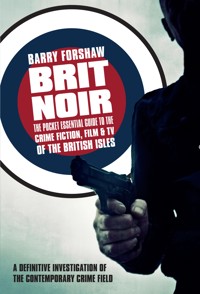

Barry Forshaw is acknowledged as a leading expert on crime fiction from European countries, but his principal area of expertise is in the British crime arena. After the success of earlier entries in the series, Nordic Noir and Euro Noir, he returns to the UK to produce the perfect reader's guide to modern British crime fiction. Every major living British writer is considered, often through a concentration on one or two key books, and exciting new talents are highlighted for the reader. Forshaw's personal acquaintance with writers, editors and publishers is unparalleled, so Brit Noir features interviews with (and quotations from) the writers, editors and publishers themselves.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 376

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Brit Noir

Barry Forshaw is acknowledged as a leading expert on crime fiction and films from European countries, but his principal area of expertise is in the British crime arena, as demonstrated in such books asBritish Crime Writing,The Rough Guide to Crime FictionandBritish Crime Film. After the success of earlier entries in this series,Nordic NoirandEuro Noir, he returns to the UK to produce the perfect reader’s guide to modern British crime fiction (taking in the best from England, Scotland and Wales,and including, for good measure, Ireland). The word ‘noir’ is used in its loosest sense: every major living British writer is considered, often through a concentration on one or two key books, and exciting new talents are highlighted for the reader.

But the crime genre is as much about films and TV as it is about books, andBrit Noiris also a celebration of the former. British television crime drama in particular is enjoying a new golden age (fromSherlocktoBroadchurch), and all of these series are covered here, as well as the most important recent films and TV in the field.

Barry Forshaw’s personal acquaintance with writers, editors and publishers is unparalleled, soBrit Noircontains a host of new insights into the genre and its practitioners.

About the Author

Barry Forshaw is one of the UK’s leading experts on crime fiction and film. His books includeNordic Noir,Sex and FilmandThe Rough Guide to Crime Fiction.Among his other work:Death in a Cold Climate,British Gothic Cinema,Euro Noirand the Keating Award-winningBritish Crime Writing: An Encyclopedia, along with books on Italian cinema and Stieg Larsson. He writes for various national newspapers, editsCrime Time(www.crimetime.co.uk), and is a regular broadcaster and panellist. He has been Vice Chair of the Crime Writers’ Association, and teaches an MA course at City University on the history of crime fiction.

Praise for Barry Forshaw

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOREURO NOIR

‘An informative, interesting, accessible and enjoyable guide as Forshaw guides us through the crime output of a dozen nations’ –The Times

‘An exhilarating tour of Europe viewed through its crime fiction’ –Guardian

‘Exemplary tour of the European crime landscape... supremely readable’ –The Independent

‘This is a book for everyone and will help and expand your reading and viewing’ –We Love This Book

‘Like all the best reference books, it made me want to read virtually every writer mentioned. And, on another note, I love the cover’ –crimepieces.com

‘If I did want to read something so drastically new, I now know where I would begin. With this book’ –Bookwitch

‘Barry Forshaw is the master of the essential guide’ –Shots Mag

‘This enjoyable and authoritative guide provides an invaluable comprehensive resource for anyone wishing to learn more about European Noir, to anticipate the next big success and to explore new avenues of blood-curdling entertainment’ –Good Book Guide

‘Fascinating and well researched… refreshing and accessible’ –The Herald

‘An entertaining guide by a real expert, with a lot of ideas for writers and film/TV to try’ –Promoting Crime Fiction

‘… a fabulous little book that is like a roadmap of Europe crime fiction’ –Crime Squad

‘Fascinated by Scandinavian crime dramas? Go to this handy little guide’– News at Cinema Books

Introduction

The current state of British crime writing

It might be argued that the low esteem in which British crime writing was held for so many years allowed it to slowly cultivate a dark, subversive charge only fitfully evident in more respectable literary fare. And precisely because genre fiction was generally accorded critical indifference (except by such astute highbrow commentators – and fans – as WH Auden), this critical dismissal was consolidated by the fact that readers – while relishing such compelling crime and murder narratives – looked upon the genre as nothing more than harmless entertainment. Since the status of crime writing was subsequently elevated by writers such as PD James, many modern writers now utilise the lingua franca of crime fiction in innovative fashion, with acute psychological insights freighted into the page-turning plots.

Similarly, informing much of the work of contemporary British crime writers – the subject of this study, as opposed to writers of the recent past or the Golden Age, or historical crime fiction – is a cool-eyed critique of modern society. But not all current practitioners are this ambitious in terms of giving texture to their work. For that matter – and let’s be frank here – a great many modern writers are little more than competent journeymen (and women); the genre is still beset by much maladroit or threadbare writing, particularly in an age of self-publishing, where editorial input is painfully conspicuous by its absence.

Nevertheless, prejudices have been eroded (hallelujah!), and crime fiction on the printed page is now frequently reviewed in the broadsheets by writers such as myself alongside more ‘literary’ genres, but often in crime column ghettos (although solus reviews are not unknown). However, literary editors – in my experience – still favour overly serious writers above those they perceive as ‘entertainers’. So, what’s the state of modern crime writing in the UK today? I’ve attempted to tackle that question in the following pages.

This is not a social history of the British crime novel, though it touches on the more radical notions of the genre; however, the ‘readers’ guide’ format I’ve used (with entries ranging from the expansive to the concise) hopefully allows for a comprehensive celebration of a lively genre – a genre, in fact, that continues to produce highly accomplished, powerfully written novels on an almost daily basis. What’s more, despite the caveats above, Britain – including Scotland (not yet cut away from the rest of the UK, despite the wishes of Ms Sturgeon and Mr Salmond) – and Ireland are enjoying a cornucopia of crime writers who have the absolute measure of the four key elements of crime writing (social comment is a bonus). And those four key elements? They are:

1. strong plotting

2. literate, adroit writing

3. complex characterisation

4. vividly evoked locales.

Murderous secrets and professional problems

Readers have plenty of cause to be thankful, as these crowded pages will demonstrate. But this wasn’t an easy book to write. The range of contemporary crime fiction (as opposed to the historical variety) in the UK is surprisingly broad, given that the geographical parameters of the British Isles and its Celtic neighbours are proscribed compared with the massive canvas of the United States. But the parochial nature of much British crime fiction might be precisely what imbues it with its customary sharpness – when murderous secrets confined in British suburban spaces are set free, the results are explosive. And then there is the perception of the British love of order (although such stereotypes are in flux at present); crime novels are particularly satisfying in that we are invited to relish the chaos unleashed by the crime and criminals before the status quo is re-established. This is a process that has a particular resonance for the British character – more so than for, say, Americans (the barely contained pandemonium of the large American city is never really tamed). Of course, when Charles Dickens and Wilkie Collins introduced several of the key tropes of crime fiction in such classics as Bleak House and The Woman in White, neither author had any thought of creating a genre. It is instructive to remember that their books, while massively popular, lacked the literary gravitas in their day that later scholarship dressed them with; this was the popular fare of the time, dealing in the suspense and delayed revelation that was later to become the sine qua non of the genre. In generic fiction, the inhabitants of 221b Baker Street and their celebrated creator are, of course, the most important factors in terms of generating an army of imitators – notably Agatha Christie’s Hercule Poirot – and Holmes clones continue to surface to this day, dressed in contemporary garb rather than deerstalker and Inverness cape but still demonstrating impressive ratiocination.

In the twenty-first century, apart from the sheer pleasure of reading a meaty crime novel, the ‘added value’ in many of the best examples is the implicit (or sometimes explicit) element of social criticism incorporated by the more challenging writers. Among popular literary genres, only science fiction has rivalled the crime novel in ‘holding the mirror up to nature’ (or society). Best-selling modern writers have kept alive this rigorous tradition, although rarely at the expense of sheer storytelling skill, the area in which the crime field virtually demolishes all its rivals. When, in recent years, crime fiction became quantifiably the most popular of popular genres (comprehensively seeing off such rivals as romance fiction), it was only the inevitable coda to a process that had been long underway, and one that should be celebrated all the more for this added value of societal critique.

Given that the issue of class is still an important one in Britain, it is surprising how little the subject exercises current writers. From the Golden Age onwards, the ability of the detective figure to move unhampered (and in insolent fashion) across social divides has always accorded the genre a range not to be found elsewhere – while this is also reflected in American hard-boiled fiction, money rather than class is the signifier there. Similarly, detectives from a patrician background are rare indeed in contemporary crime; it has taken an American writer setting her books in Britain, Elizabeth George, to keep the Sayers/Wimsey blueblood tradition alive with her aristocratic sleuth Lynley. Most of the slew of coppers who populate the genre are middle- or lower middle-class but sport a bolshiness that suggests working-class resentment – think of Rankin’s Rebus, Billingham’s Thorne et al. The resentment of the (often) male policeman, however, is generally reserved for his superiors (who are constantly attempting to take him off sensitive cases) or the intransigence of the system he is obliged to deal with.

In terms of gender, while the middle-aged, dyspeptic (and frequently alcoholic) male copper still holds sway, eternally finding it difficult to relate to his alienated family, the female equivalent is the woman who has achieved a position of authority but who is constantly obliged to prove her worth – and not necessarily in terms of tackling male sexism, although that issue persists as a useful shorthand. The influential figure of Lynda La Plante’s Jane Tennison has to some extent been replaced by women who simply get on with the job – and their professional problems are predicated by the fact that they are simply better at solving crime than their superiors: in other words, a mirror image of the male detective. This hard-to-avoid uniformity inevitably makes it difficult for writers to differentiate their bloody-minded female protagonists from the herd, but ingenuity is paramount here – one female detective in the current crop, for instance (MJ Arlidge’s DI Helen Grace), differs from her fellow policewomen in having an inconvenient taste for rough sex and S&M.

About the book

Looking at mainstream crime fiction in the modern age (and leaving aside the legacy of the past), it is clear that the field is in ruder health than it has ever been. In fact, such is the range of trenchant and galvanic work today that an argument could be made that we are living in a second Golden Age.

The remit of this study has been as wide as possible: every genre that is subsumed under the heading of ‘noir’ crime fiction is here, from the novel of detection to the blockbuster thriller to the occasional novel of espionage (though they are the exception). But – please! – don’t tell me that some of the authors here are not really ‘noir’; let’s not get locked into a discussion of nomenclature. ‘Noir’ here means ‘crime’ – the distinctly non-noir Alexander McCall Smith may not want to be included, but he is. My aim here was – simply – to maximise inclusivity regarding contemporary British crime writing (historical crime apart – that’s another book), whether from bloody noir territory to the sunnier, less confrontational end of the spectrum.

I offer preliminary apologies to any writers from the Republic of Ireland, who may be fervent nationalists and object to appearing in a book called Brit Noir; their inclusion is all part of my agenda of celebrating as many interesting and talented writers as I can. Although it’s not quite the same, sometime before the last Scottish referendum, I asked both Val McDermid and Ian Rankin if they would still want to be included in a study of British crime writers if the vote were ‘yes’ to cutting loose from the UK, or if they ought to be dropped as they were now foreigners. Both opted for the former option.

It should be noted that Brit Noir is principally designed to be used as a reference book to contemporary crime – i.e. (mostly) current writers – as opposed to a text to be read straight through. But if you want to do the latter, how can I stop you? And you’ll note that I’ve erred on the side of generosity throughout, avoiding hatchet jobs; in a readers’ guide such as this, I feel that should be the modus operandi.

A note on locating authors in Brit Noir

One problem presented itself to me when writing this study (well, a host of problems, but let’s just stick with one). If the layout of the book were to be geographical – i.e. placing the work of the various authors in the regions where they have their detectives operating – that would be fine with, say, Ian Rankin, who largely keeps Rebus in Edinburgh. But what about his fellow Scot Val McDermid? Her Tony Hill/Carol Jordan books are set mostly in the North of England – and, what’s more, in the fictitious city of Bradfield. Should I have a section for ‘Bradfield’ with just one author entry? And what about those authors who set their work in unspecified towns? You see my problem, I hope – but that wasn’t all. What about the writers with different series of books set in different places, such as Ann Cleeves? Or Brits who place their coppers in foreign cities? I briefly considered elaborate cross-referencing, but decided I’d rather use my energies in other areas. So here’s the solution: if you want to find a particular author, don’t bother trying to remember the setting of their books and thumbing fruitlessly through the Midlands or the North West. Simply turn to the index at the back of the book, which will tell you precisely where to find everyone.

Section One: The novels and the writers

England and Wales

London

Success was something of a double-edged sword for MO HAYDER with her début novel Birdman: the book enjoyed astonishing sales, but called down a fearsome wrath on the author for unflinchingly entering the blood-boltered territory of Thomas Harris’s Hannibal Lecter books. Part of the fuss was clearly to do with the fact that a woman writer had handled scenes of horror and violence so authoritatively, and there was little surprise when the subsequent The Treatment provoked a similar furore. Actually, it’s a remarkably vivid and meticulously detailed shocker: less grimly compelling than its predecessor, perhaps, but still a world away from the cosy reassurance of much current crime fiction. In a shady south London residential street, a husband and wife are found tied up, the man near death. Both have been beaten and are suffering from acute dehydration. DI Jack Caffery of the Met’s murder squad AMIP is told to investigate the disappearance of the couple’s son, and, as he uncovers a series of dark parallels with his own life, he finds it more and more difficult to make the tough decisions necessary to crack a scarifying case. As in Birdman, Caffery is characterised with particular skill, and Hayder is able (for the most part) to make us forget the very familiar cloth he’s cut from. The personal involvement of a cop in a grim case is an over-familiar theme, but it’s rarely been dispatched with the panache and vividness on display here.

Is there anyone else in the crime genre currently writing anything as quirky and idiosyncratic as CHRISTOPHER FOWLER’s Bryant and May series? (And let’s disabuse readers of the mistaken notion that this is a historical series, as many seem to think – it wouldn’t be in this book if it were.) Fowler eschews all recognisable genres, though the cases for his detective duo have resonances of the darker corners of British Golden Age fiction. In Bryant & May and the Bleeding Heart, the Peculiar Crimes Unit is handed a typically outlandish case in which two teenagers have seen a corpse apparently stepping out of its grave – with one of them subsequently dying in a hit-and-run accident. Arthur Bryant is stimulated by the bizarreness of the case but is tasked with finding out who has made away with the ravens from the Tower of London. (Not an insignificant crime, as it is well known that when the ravens leave the Tower, Britain itself will fall.) The usual smorgasbord of grotesque incident and stygian humour is on offer, and if you aren’t already an aficionado, I suggest you find out what the fuss is about before the forthcoming television series clinically removes Fowler’s individual tone of voice.

It is both a virtue and a curse when one doesn’t require a great deal of sleep. Sometimes – when I’m wide awake in the wee small hours with only the sound of urban foxes outside my window suggesting something else is alive – I feel that I’d prefer to be like ordinary people who need eight hours’ shuteye. But here’s the virtue of this unusual state: it gives one ample time to catch up with all the writers one wants to read; sometimes they are old favourites, sometimes new discoveries. And – a real pleasure – sometimes in these nocturnal explorations I encounter the work of a writer who (while moving in familiar waters) demonstrates an innovative and quirky imagination, transforming narratives with whose accoutrements we’re familiar. Debut writer SARAH HILARY was most decidedly in that category, and even though her character DI Marnie Rome may initially appear to owe something to other female coppers (Lynda La Plante’s Tennison, for example), Marnie turns out to be very much her own woman – as is Hilary herself, with her crisp and direct style.

In Someone Else’s Skin, DI Rome is dispatched to a woman’s shelter with her partner DS Noah Jake. Lying stabbed on the floor is the husband of one of the women from the shelter. Rome finds herself opening the proverbial can of worms, and a slew of dark secrets will be exposed before a final violent confrontation in a kitchen. As well as functioning as a well-honed police procedural, this is very much a novel of character – DI Rome in particular is strikingly well realised, and even such issues as domestic abuse are responsibly incorporated into the fabric of the novel. Someone Else’s Skin is a book that hits the ground running, and readers will be keen to see more of the tenacious Marnie Rome.

With SJ WATSON’s Before I Go To Sleep, British publishing saw something of a phenomenon. Watson may have borrowed the book’s central premise from Christopher Nolan’s film Memento (memory-deprived protagonist struggling to make sense of their life), but the assurance with which he finessed his narrative belied his inexperience and rivalled that of such old hands as Robert Harris. Watson’s follow-up novel in 2015 was Second Life.

The refreshingly forthright STELLA DUFFY has made a success of several careers: in the theatre, in broadcasting and as the creator of a variety of books in different genres (including the historical field). As with the earlier work of Val McDermid, Duffy’s protagonist is a lesbian, the private investigator Saz Martin, who has been put through her paces in such tautly written, quirky novels as Fresh Flesh. There is a social agenda behind the books, but never at the expense of the exigencies of strong, persuasive storytelling.

For some time now, MARK BILLINGHAM’s lean and gritty urban thrillers featuring DI Tom Thorne have been massive commercial successes. And such books as In the Dark, a standalone novel in which Thorne makes only a cameo appearance, demonstrate that Billingham can make trenchant comments about British society while never neglecting his ironclad narrative skills. Billingham, who has a background in stand-up comedy, has quoted some interesting statistical findings in his talks to book groups: many women would rather spend time reading a thriller than having sex. Billingham appears to be bemused by this statistic, but (if the truth were told) the author himself is part of the problem: his crime novels are undoubtedly a source of pure enjoyment (without the bother of having to take off one’s clothes), although thrillers such as Lifeless are journeys into the most disturbing aspects of the human psyche. It’s interesting that Billingham’s books have a reputation for extreme violence, because they deal more in atmosphere – a real sense of dread is quietly conveyed to the reader.

In Buried, ex-DCI Mullen, a retired police officer, is distressed when his son disappears. Is he the victim of a kidnapping? Tom Thorne begins his inquiry by seeking everyone who might have a score to settle with the boy’s father. And he discovers something intriguing: Mullen has not mentioned the person who would appear to be the prime suspect – a man who had once made threats against Mullen and his family and who, moreover, is under suspicion for another killing. Billingham always does considerable research for his books to ensure the authenticity of his police detail, but he was obliged to make up some of the procedural aspects here as the Met is particularly secretive on the issue of kidnapping. Billingham avoids the obvious set pieces that can instantly pique the reader’s attention, and ensures that Thorne’s encounter with evil is handled in a dispassionate fashion, even though Thorne himself is less strongly characterised than usual in this, his sixth outing. The recent Time of Death (the thirteenth Thorne) is Billingham on top form.

LAURA WILSON’s work bristles with some of the best crime writing in the UK – she is one of the country’s most searching psychological novelists working in the genre. There are also ghosts of one of Wilson’s favourite novelists, Patrick Hamilton, in the luminous and richly detailed conjuring of the London of various eras in her books. Wilson has never been happy staying within the parameters of the conventional crime novel, and in My Best Friend she deploys a device whereby the novel is narrated by three strongly delineated protagonists. Her most recent work features her sympathetic copper Ted Stratton, while one of her most accomplished books is 2015’s contemporary (non-Stratton) The Wrong Girl.

Many well-heeled TV presenters face a variety of pitfalls that could sabotage their comfortable lives: a messy divorce, inconvenient revelations about their private life. But Gaby Mortimer, heroine of SABINE DURRANT’s Under Your Skin, finds something more sinister to threaten her equilibrium. When running on the common near her London house, she discovers the body of a woman lying in the brambles, the victim of a savage strangling. But what Gaby is not expecting is the fact that she is to become the principal suspect for the crime. (The murder victim was wearing Gaby’s T-shirt, and ever more damning evidence begins to point in her direction.) The police appear to be convinced of Gaby’s guilt, but despite this, she tries to keep her life on track. But as many a TV personality (and politician) has found, it’s virtually impossible to carry on with the day job when you are under scrutiny by reporters, and all around people regard you with suspicion. Things can only get worse – and they do, to the extent that Gaby begins to doubt her own sanity. But then an attractive journalist called Jack appears, apparently believing in Gaby’s innocence and ready to help. Gaby’s troubles, however, are only just beginning. Durrant has written for teenage girls, but there is absolutely nothing adolescent about this strikingly constructed and economically written thriller, a book that steadily draws the reader into the plight of its besieged heroine and springs a variety of surprises – surprises we are unable to second-guess. And both male and female readers find it easy to identify with Gaby, with the underpinnings of her life relentlessly pulled away. In fact, she is the kind of woman in extreme situations that Nicci French used to write about before turning to a series character, and Under Your Skin has all the authority of the best novels by French. Durrant’s treatment of the characters’ psychology is, admittedly, straightforward rather than nuanced, but that strategy ensures that the inexorable grip never slackens. Let’s hope that she continues to spend her time writing for adults: we need thriller writers who can reinvigorate the genre – and it looks like Durrant may be able to do just that.

The amazing – and immediate – success of MARTINA COLE’s crime novels must be a source of despair to those writers who have struggled for years. Right from the start, she has enjoyed reader approval for her distinctive, gritty fiction. Even the workaday TV adaptations of Dangerous Lady and The Jump merely brought more kudos her way (she’s been less lucky than Colin Dexter in her transfer to the screen – but with her sales, she should worry). In Broken, a child is abandoned in a deserted stretch of woodland and another on the top of a derelict building. DI Kate Burrows makes the inevitable connections, and when one child dies, she finds herself up against a killer utterly without scruples. Her lover Patrick offers support in this troubling case, but he is under pressure himself. A body is found in his Soho club, and Patrick is on the line as a suspect. And Kate begins to doubt him… In prose that is always trenchant, Cole delivers the goods throughout this lengthy and ambitious narrative. Kate is an exuberantly characterised heroine, and the sardonic Patrick enjoys equally persuasive handling from the author. The Good Life – which Cole has certainly earned the right to enjoy – continued her run of bestsellers (as did, most recently, Get Even).

Speaking to MICK HERRON, I learned about his adept use of London locations. ‘I rarely choose locations: research averse, I’ve found that my novels tend to be set in the areas I frequently inhabit. Silicon Roundabout is a whirling dervish of a road junction that comes into its own on winter afternoons, when dark arrives early, and the advertising hoardings scream out their video messages above the red and white kaleidoscope made by furious traffic. Few things are as irresistibly noir as neon. It’s like glitter laid on grime; a cheap makeover that only looks good as long as the light is bad. So it’s round here that I have Tom Bettany wander in Nobody Walks: unkempt and haggard, carrying his dead son’s ashes in a bag, he circles the streets looking for drug dealers among those who haunt the bars and bop the night away. What he finds isn’t quite what he thought he was looking for, but that too is an aspect of noir – that you can’t avoid the fate that awaits you, whichever streets you choose to wander down.’ Herron’s 2016 novel Real Tigers has received enthusiastic early notices.

Perhaps because of a reaction against what detractors called the laddish fiction of TONY PARSONS (although he clearly had complex strategies in play in his examination of sex and relationships), the writer has recently taken a new direction, reinventing himself in The Murder Bag as a pugnacious crime writer – although even in this new venture he has encountered resistance. If you are shell-shocked from the army of novels featuring tough maverick cops – and are convinced that nothing new can invigorate the genre – perhaps you should pick up The Murder Bag. Yes, we’ve met detectives at loggerheads with their daughters (as here) before, from Wallander to Rebus. But there are two things that instantly lift this one out of the rut: parenting is a speciality of the author’s work and it’s treated with a nuance largely absent elsewhere in crime fiction. And Parsons, a quintessential London writer, evokes his city with pungency. Bolshie DC Max Wolfe is investigating a homicide in which a banker’s throat has been cut; a second victim is a homeless heroin addict. The connection: an upscale private school. This first crime novel was followed by The Slaughter Man.

LYNDA LA PLANTE – the creator of Prime Suspect – is a woman of conviction. Many things clearly make her blood boil – not least the way in which she perceives this country’s justice system as being heavily weighted on the side of the criminal rather than the victim, and the ease with which violent sexual offenders can work the system and be back on the streets in a derisorily short time. Authors frequently remind us that the views of their characters are not necessarily their own, but after reading a typical La Plante novel there can be little doubt that it’s the author’s persuasive (and often incendiary) views that leap off the page – not least because they are espoused in the book not just by the unsympathetic misogynist coppers, but also by the driven DCI James Langton and even La Plante’s vulnerable but tough heroine DI Anna Travis.

In Clean Cut, Langton is in pursuit of a truly nasty group of illegal immigrants who have murdered a young prostitute. Then Langton himself is viciously slashed in the chest and leg with a machete and hospitalised – with the prospect of his police career coming to an end. Langton is conducting a clandestine affair with another detective, DI Anna Travis, who has a similarly daunting load on her shoulders: a fierce commitment to the job, battles with boneheaded colleagues, and a readiness to place herself in highly dangerous situations. But her biggest problem is her fractious relationship with the withholding Langton – difficult enough in his selfishness and lack of commitment before he is brutally wounded, but almost insufferable as he concentrates his frustration on Anna whenever she visits his nursing home. She is working on another, related case in which the body of a woman has been found sexually assaulted and mutilated – and soon Travis and Langton are up against something far more sinister than squalid people trafficking (involving voodoo, torture and a truly monstrous villain).

There are various factors that ensure Clean Cut is a visceral read: the assured plotting, the pithy heroine (we’re always on Anna’s side, even though we are irritated by her desperate reliance on a man who treats her so badly), and the poisonous secret that the heroine is left with at the end of the book. But it’s La Plante’s passionate conviction (burnt into the pages) that society has become the hostage of criminals that really gives the book its charge. In 2015, we were given a glimpse into the early professional life of La Plante’s signature character with Tennison, tied into a new TV adaptation.

The inaugural novel in a new series of London-set thrillers by a then-new (now established) British writer had all the hallmarks of staying power. SIMON KERNICK’s The Business of Dying showed that the author meant business; and the plotting is as cogent as you’ll find this side of the Atlantic. DS Dennis Milne is a maverick copper with a speciality sideline in killing drug-dealing criminals. But everything goes wrong for him when (acting on some bad advice) he kills two straight customs officers and an accountant. At the same time, he is investigating the brutal murder of an 18-year-old working girl, found with her throat ripped open by Regent’s Canal, and his probing leads him towards other police officers. Soon, it’s up for grabs as to whether Milne will go down for his own illegal dealings before he cracks a case that is steeped in blood and corruption. Since this debut, Kernick has rarely failed to deliver tough and authentic storytelling in book after book. Another theme of that first novel was the transitoriness of so much that we hold dear in life (ironically, even before the novel was published, two of the three Kings Cross gas rings that adorned the hardback jacket were swept away by Eurostar… nothing is permanent, as Kernick’s rugged novel argued).

The unvarnished writing of DAVID LAWRENCE gleaned much praise; both The Dead Sit Round in a Ring and Nothing Like the Night demonstrated that a gritty talent had appeared on the crime genre. Initial success, of course, can be a double-edged sword, but Lawrence showed no sign of faltering, and Cold Kill had the same steely assurance as its predecessors. When a woman’s body is found in a London park, DS Stella Mooney finds herself involved. Robert Kimber confesses to the murder; his flat appears to reveal all the apparatus of a killer, with its photos of young women and grim text written about each of them. Other murders, equally savage, seem to be down to him, but Stella is not convinced. Is someone else manipulating the disturbed Kimber? All of this is handled with the forcefulness we have come to expect from Lawrence, with Stella Mooney as fully rounded a protagonist as ever. And if revelations in the plotting owe something to Thomas Harris, Lawrence is hardly alone in drawing water from that particular much-visited well. Nevertheless, he remains his own man, and Cold Kill is authoritatively gripping. Early success, however, was not followed up.

ANDREW MARTIN (a man who does not hesitate to say exactly what he means on any occasion) may be well known for his award-winning historical crime series featuring railway detective Jim Stringer, but he had hankered to write a novel about the super-rich, partly in the hope (he noted) that it might make him at least slightly rich. And while people are fascinated by the moneyed, he hadn’t noticed many crime novels on the subject. It might be asked: why would the super-rich resort to crime? They would need a very good reason. And Martin set himself other challenges. The super-rich of London are mainly foreign, and he has succeeded in getting those voices – specifically Russian ones – right. Martin’s approach to multiculturalism, which he decided to take on after spending many years imaginatively inhabiting the mono-cultural world of Edwardian Britain, is provocative. The Yellow Diamond concerns an imaginary unit of the Metropolitan Police set up to monitor the super-rich of London. It’s based in dowdy Down Street, at the ‘wrong’ end of Mayfair. A principal character is a woman in her fifties, Victoria Clifford, who was the waspish personal assistant to the senior detective who set up the unit. However, he was rendered comatose by a bullet soon afterwards, and Clifford must find out why he was attacked.

Many of us have had friends who seem relentlessly bound on self-destruction – and not just by the time-honoured route of drink or drug abuse. The loss of their job is the inevitable corollary – but how do we save those friends, when anything we say sounds hollow or sanctimonious? The trick of NICCI FRENCH’s highly persuasive Catch Me When I Fall is to embody such notions in the reckless protagonist, Holly, who risks her happy marriage and successful career by venturing into dangerous terra incognita: alcohol-fuelled semi-orgies, where she risks brutal beatings, and wakes up from her stupor to find she’s been having sex with some highly unsuitable partners – one of whom breaks out of the confines of her alternative existence and threatens her fragile everyday life. But there’s an intriguing sleight of hand at work here: while the reader might be tempted to metaphorically shake Holly by the shoulders and suggest she gets her act together, French makes such a comfortable distancing impossible by involving us in Holly’s increasingly nightmarish life. We’re forced to lose our objectivity, and we find ourselves taking on Holly’s guilty actions as part of our own response to the book. The ‘transference of guilt’ theme was a speciality of Alfred Hitchcock, but nothing that the director made could match the positive riot of guilt transference that decorates the pages of Catch Me When I Fall: Holly’s best friend/business partner Meg is ineluctably drawn into the chaos of her life, as are Holly’s husband and various other characters in the novel, including a sympathetic male, Stuart, who unwisely confides to her his problems with premature ejaculation. And, finally, there’s the guilt dumped on the reader, obliged to take on the consequences of Holly’s actions, whether we want to or not. The novel, like so much of French’s work, hardly makes for a comfortable read. ‘Nicci French’ is, of course, the personally engaging husband-and-wife team of Nicci Gerrard and Sean French, and this book, more than most of their work, poses some intriguing gender-related questions about the duo’s division of labour: a female protagonist, as ever, but initially the lack of balanced male figures is worrying. In fact, the preponderance of brutal, weak or drippily complaisant males suggests another author named French – Marilyn – and The Women’s Room (with its simple antithesis of female=good, male=bad), but Nicci French is much too sophisticated a writer for that, and some of the men – even those with less-than-honourable motives – are shown to be victims as much as Holly. Is this Sean French putting in tuppence for the male sex? We’ll never know, as the couple rigorously avoid telling who does what. And who cares when the results are as dexterous and edgy as this?

More recent work involves a series protagonist, therapist Dr Frieda Klein, who first appeared in Blue Monday. In Tuesday’s Gone, a social worker, Maggie, calls on the disturbed Michelle Doyce, a ‘care in the community’ patient. Maggie is struck by the smell and the squalor – hardly new experiences for her – but she is not prepared for the man sitting in a back room, whose blue marbled appearance is that of a corpse. Frieda Klein is dragooned into the case by her colleague DCI Karlsson, and the dead man is identified as confidence trickster Robert Poole. Klein and Karlsson soon encounter an army of the dead man’s unlucky ‘marks’ – and Frieda discovers that whoever is responsible for the death of Poole has her in their sights. Solid, assured work, if less distinctive than their memorable standalones.

ALI KNIGHT’s artfully constructed crime novels are set in London, with the recent Until Death a persuasive entry; it is a domestic noir thriller set mainly in the penthouse on top of St Pancras station. From every window of this gothic architectural masterpiece, the dynamism, bustle and freedom of London can always be seen, contrasting chillingly with the claustrophobia and secrets of the family who live there.

It took some time, but FRANCES FYFIELD has now acquired something close to the literary gravitas of the two late British Queens of Crime (and habitués of the House of Lords), Mesdames Ruth Rendell and PD James. Fyfield is now regularly identified as one of the heirs of a great tradition, and books such as Staring at the Light have mined the same vein of psychological acuity and dark menace as those of her fellow authors. Fyfield said to me that the ideal locale for a story is a small community where everyone thinks they know everything about one another, while really they miss the obvious. This is a key notion in all her books: nothing is quite what it seems. And – like all the best crime writers – her books aren’t just about keeping us glued to the chair while our cocoa goes cold; they often have something pertinent to say about the human condition (though never in any po-faced fashion).

Fyfield’s novels featuring Crown Prosecutor Helen West and DCS Geoffrey Bailey have built up a steady following, but more recent books take Fyfield’s customary delving into the darker aspects of the human psyche to a new level of intensity – and that’s very much the case with The Art of Drowning. Dedicated male readers of the author (and they are many – Fyfield’s fiefdom is by no means an exclusively female one) have been a little unsettled by her recurring theme of male violence against women, and some of the men in The Art of Drowning are as distasteful a group of males as she has created. Such as Rachel Doe’s lover, whom she discovers to be both a thief and a liar. Looking at her life (and not liking what she sees), Rachel tries a new tack: an art class, where she falls under the spell of ex-model Ivy Wiseman. Ivy is good company, having survived drug addiction, the death of her child and the loss of her home, and, like Rachel, she’s a casualty of the sex war. When the women visit Ivy’s parents, who have an idyllic, slightly rundown place near the sea, she begins to find true peace again with her new friends. Then she is told of the death of Ivy’s daughter, who died by drowning. And she hears about the unpleasant Carl, Ivy’s ex-husband (a lawyer), who her parents want to track down. Rachel decides to help them find him – but when she meets the sinister Carl, everything she had expected proves to be subtly off-kilter. She finds herself desperately out of her depth, and soon discovers that a savage internecine war within a family is not a good place to be. As ever with Fyfield, the characters here are indelibly etched – everyone from the vulnerable Rachel to the ambiguous people under whose spell she falls is drawn with tremendous vividness. And the plotting! If you feel that your unwritten novel will take the world by storm, don’t pick up The Art of Drowning; you may be discouraged from setting fingers to keyboard.

In Hunted, EMLYN REES has produced a novel that will have you holding your breath throughout – possibly to the detriment of your health. Danny Shanklin comes to consciousness in a London hotel room he’s unfamiliar with. He’s dressed in a balaclava and a red tracksuit. On the floor is a faceless corpse – and Shanklin has a high-powered rifle strapped to his hands. Hearing the sound of sirens, he looks out of the window and sees a burning car and more bodies littering the street. This is the powerful opening to a truly kinetic piece of crime/thriller fiction, in which the stakes are always set at the highest level.

You’re a highly successful writer of children’s books featuring a kind of junior James Bond. Does this have you chafing at the bit, keen to cram an adult book with all the sex and violence you can’t put into your books for a youthful audience? ANTHONY HOROWITZ’s first novel for adults, The Killing Joke, gave older readers a chance to see whether the author had less sanitised entertainment up his sleeve.

Horowitz grew up tended by servants in his family’s London mansion, the scion of a well-heeled Jewish family. As he has remarked, his childhood was deeply unhappy – and it’s an upbringing he brought to scarifying life in such autobiographical books as Granny. He made a mark as a children’s author with his Alex Rider novels; the adventures of Horowitz’s youthful spy have sold over a million copies in this country alone. But this is only one string to his bow: his screenplay The Gathering has been filmed, and his TV scriptwriting includes the BAFTA-winning Foyle’s War.

The auguries were good for The Killing Joke, his first un-child-friendly novel. This is a scorchingly funny black comedy thriller in which none-too-successful actor Guy Fletcher overhears a sick joke about his estranged mother, a well-known actress, in a Finsbury Park pub. He ill-advisedly objects to the joke-teller – a brutal cockney builder – and is floored by a headbutt for his objections. This starts Guy on a bizarre odyssey to discover where all jokes originate – and, yes, there is one source, which Guy discovers – while putting his life in considerable danger. There is a real sense here of an author stretching his wings after the constraints of writing for children – the humour is very dark. Not that such territory is off limits for kids these days; a sex scene in a fairground, however, is another matter. Guy and his companion Sally force their way into a closed funhouse and enjoy each other on a carpet of plastic balls, while distorting mirrors reflect a grotesque (and very funny) version of the erotic cavortings. The humour in The Killing Joke is laugh-out-loud stuff, and Guy is a sympathetic hero; if what he finds at the end of his quest for the source of jokes is something of a let-down after the brilliantly sustained, tortuous plotting that precedes it, most readers will feel they’ve had more than their money’s worth. Moving away from humour, recent work has been in the area of Conan Doyle and Ian Fleming pastiches.

ERIN KELLY has written a variety of novels of psychological suspense, of which The Burning Air is perhaps the most disturbing – and also the one that lays out most clearly the corrosive areas she moves in. Her first two books, The Sick Rose and The Poison Tree, borrowed titles from William Blake, but The Burning Air takes on most tellingly Blake’s line about a destructive and dark secret love.