9,59 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Oldcastle Books

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Sprache: Englisch

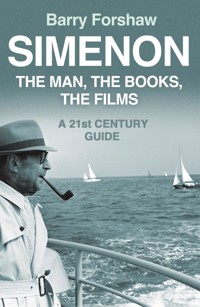

The legendary Georges Simenon was the most successful and influential writer of crime fiction in a language other than English; André Gide called him 'the greatest French novelist of our times'. Celebrated crime fiction expert Barry Forshaw's informed and lively study draws together Simenon's extraordinary life and his work on both page and screen. By the time of Simenon's death in 1989, his French detective Maigret had become an institution, rivalled only by Sherlock Holmes. The pipe-smoking Inspector of Police is a quietly spoken observer of human nature who uses the techniques of psychology on those he encounters (both the guilty and the innocent) - with no rush to moral condemnation. Simenon's non-Maigret standalone books are among the most commanding in the genre, and, as a trenchant picture of French society, his concise novels collectively offer up a fascinating analysis. And his influence on an army of later crime writers is incalculable. Alongside his own considerable insights, Barry Forshaw has interviewed people who worked either with Simenon or on his books: publishers, editors, translators, and other specialist writers. He has created a literary prism through which to appreciate one of the most distinctive achievements in the whole of crime fiction.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 287

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR BARRY FORSHAW

‘Entertaining and informative companion… written by the person who probably knows more than anyone alive about the subject’

TIMES

‘Essential reading for anyone seeking clues’

GUARDIAN

‘Highly accessible guide to this popular genre’

DAILY EXPRESS

‘Exemplary tour of the European crime landscape... Supremely readable’

INDEPENDENT

‘Fascinating and well researched… refreshing and accessible’

HERALD

‘A work to read for pleasure and instruction and then to keep on the reference shelf’

OBSERVER

‘Readers should start with Forshaw’s pocket guide to the genre’

FINANCIAL TIMES

‘If you want to know who or what is the next big thing, get this book’

EVENING STANDARD

FOREWORD

Georges Simenon created a furore worthy of the most bed-hopping of politicians with his declaration that he had had sex with over 10,000 women. He made the claim in January 1977 in a conversation with Fellini in the magazine L’Express to launch Fellini’s film Casanova in France, but the jaw-dropping statement was met with scepticism. How had he written so many novels if his entire time seems to have been spent in carnal abandon? Simenon admirers were alienated by what seemed like boastfulness – but, fortunately, it’s not necessary to approve of all a writer’s statements to admire his work. Leaving such things aside, by the time of his death in 1989, Simenon was the most successful writer of crime fiction in a language other than English in the entire field, and his most iconic creation, the pipe-smoking police inspector Jules Maigret, had become an institution. At the same time, his non-Maigret standalone novels are among the most commanding in the genre (notably The Snow Was Dirty, an unsparing analysis of the mind of a youthful criminal). Simenon created a writing legacy quite as substantial as many more ‘serious’ French literary figures; André Gide’s assessment of him as ‘the greatest French novelist of our times’ may have been hyperbolic, but as a trenchant picture of French society, Simenon’s books collectively forge a fascinating analysis.

But at this point, let’s establish what this book isn’t. It’s not designed as a straightforward biography – I felt that a sort of ‘collage’ approach might fruitfully present a picture from various angles (the author’s life and character, his remarkable literary achievements, and the many adaptations of his work in other media). To that end, apart from my own essays, I have interviewed a variety of people who either worked with him or worked on his books: publishers, editors, translators, and other specialist writers, some of whom I commissioned to write pieces on Simenon in the past for various books and magazines (notably Crime Time, which I have edited in both print and online formats). My hope is that all of this will create a prism through which to appreciate one of the most distinctive achievements in the whole of crime fiction.

Musical Chairs and Titles

At the heart of this study is a bibliography created by the late David Carter, which remains a very well-researched piece of work. Inevitably, of course, some of David’s information reflected the time when it was written (2003), so I have customised a great many things – not least adding newly translated titles for books that have appeared previously under different monikers. A good example might be the first Maigret, originally published in 1931 as Pietr-le-Letton but subsequently appearing as both Maigret and the Enigmatic Lett and The Case of Peter the Lett, and which is now available under the more suitable title of Pietr the Latvian (in a translation by David Bellos). My yardstick in terms of titles has been the impressive Penguin initiative of new translations, which are unlikely to be bettered. I have kept some of David’s plot synopses along with some of his value judgements, although, here again, I have added and subtracted extensively. Finally, though, as a starting point for this book, David’s work has been extremely useful.

SIMENON: THE MAN

A One-Man Trojan Horse

Crime in translation may have achieved massive breakthroughs in the twenty-first century, but long before this trend, Simenon was a one-man Trojan horse in the field. Georges Joseph Christian Simenon was born in Liège on 13 February 1903; his father worked for an insurance company as a clerk, and his health was not good. Simenon found – like Charles Dickens in England before him – that he was obliged to work off his father’s debts. The young man had to give up the studies he was enjoying, and he toiled in a variety of dispiriting jobs (including, briefly, working in a bakery). A spell in a bookshop was more congenial, as Simenon was already attracted to books, and his first experience of writing was as a local journalist for the Gazette de Liège. It was here that Simenon perfected the economical use of language that was to be a mainstay of his writing style; he never forgot the lessons he acquired in concision. Even before he was out of his teenage years, Simenon had published an apprentice novel and had become a leading figure in an enthusiastic organisation styling itself ‘The Cask’ (La Caque). This motley group of vaguely artistic types included aspiring artists and writers along with assorted hangers-on. A certain nihilistic approach to life was the philosophy of the group, and the transgressive pleasures of alcohol, drugs and sex were actively encouraged, with much discussion of these issues – and, of course, the arts were hotly debated. All of this offered a new excitement for the young writer after his sober teenage years. Simenon had always been attracted to women (and he continued to be enthusiastically so throughout his life) and in the early 1920s he married Régine Renchon, an aspiring young artist from his home town. The marriage, however, was troubled, although it lasted nearly 30 years.

From the City of Lights to the USA

Despite the bohemian delights of the Cask group, it was of course inevitable that Simenon would travel to Paris, which he did in 1922, making a career as a journeyman writer. In these early years, he published many novels and stories under a great variety of noms de plume.

Simenon took to the artistic life of Paris like the proverbial duck to water, submerging himself in all the many artistic delights at a time when the city was at a cultural peak, attracting émigré writers and artists from all over the world. He showed a particular predilection for the popular arts, starting a relationship with the celebrated American dancer Josephine Baker after seeing her many times in her well-known showcase La Revue Nègre. Baker was particularly famous for dancing topless, and this chimed with the note of sensuality that was to run through the writer’s life. As well as sampling the fleshpots, along with more cerebral pursuits, Simenon became an inveterate traveller, and in the late 1920s he made many journeys on the canals of France and Europe. There was an element of real-life adventure in Simenon’s life at this time, when he became an object of attention for the police while in Odessa (where he had made a study of the poor). His notes from this time produced one of his most striking novels, The People Opposite/Les Gens d’en Face (1933), which was bitterly critical of the Soviet regime, which the author saw as corrupt. As the 1930s progressed, Simenon temporarily abandoned the police procedural novels featuring doughty Inspector Maigret (his principal legacy to the literary world), but he did not neglect his world travels, considering that the more experience of other countries he accrued, the better a writer he would be.

Like many people in France, Simenon’s life was to change as the war years approached. In the late 1930s, he became Commissioner for Belgian Refugees at La Rochelle, and when France fell to the Germans, the writer travelled to Fontenay in the Vendée. His wartime experiences have always been a subject of controversy. Under the occupation, he added a new string to his bow when a group of films was produced under the Nazis based on his writing. It was, perhaps, inevitable that he would later be branded a collaborator, and this stain was to stay with him for the rest of his career. In the 1940s, while in Fontenay, Simenon became convinced that he was going to die when a doctor made an incorrect diagnosis based on an X-ray. Pierre Assouline’s biography argues that this mistake was cleared up very quickly, but this erroneous sentence of death affected Simenon deeply and led to the writing of the autobiographical Pedigree about the writer’s youth in Liège. The novel – Simenon’s longest by far – was written between 1941 and 1943 but not published until 1948.

After the war, Simenon decided to relocate to Canada, with a subsequent move to Arizona. The USA had become his home when he began a relationship with Denyse Ouimet, and his affair with this vivacious French Canadian was to be highly significant for him, inspiring the novel Three Bedrooms in Manhattan/Trois Chambres à Manhattan (1946). The couple married, and Simenon moved yet again, this time to Connecticut. This was a particularly productive period for him as a writer, and he created several works set in the USA, notably the powerful Red Lights in 1955, which, in its scabrous picture of the destructive relationship between a husband and wife, echoed the tough pulp fiction of James M. Cain. He also tackled organised crime in The Brothers Rico/Les Frères Rico in 1952 (subsequently filmed). However, always attracted by the prospect of a new relationship, Simenon began to neglect his wife and started an affair with a servant, Teresa Sburelin, with whom he set up house. (His wife Denyse spent some time in psychiatric clinics but outlived her husband by six years. She was a published author, and even practised as a psychiatrist for a time.)

In the 1950s, Simenon and his family returned to Europe, finally settling in a villa in Lausanne. Here, behind closed doors, he would enter an almost trancelike state, would write compulsively, usually completing an entire book in a week or two.

Simenon and Maigret

It quickly became clear that Simenon was the most successful writer of crime fiction (in a language other than English) in the entire genre, and his character Maigret had become as much of an institution as the author. The Simenon novels that can be described as standalones (i.e. books with no recurring detective figure) are among the most powerful in the genre, but there is absolutely no debate as to which of his creations is most fondly remembered: the pipe-smoking French Inspector of Police, Jules Maigret. The detective first appeared in the novel Pietr the Latvian/Pietr-le-Letton in 1931, and the author stated that he utilised characteristics that he had observed in his own great-grandfather. Almost immediately, all the elements that made the character so beloved were polished by the author: Commissaire in the Paris police headquarters at the Quai des Orfèvres, Maigret is a much more human figure than such great analytical detectives as Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes, and his approach to solving crimes is usually more dogged and painstaking than the inspired theatrics of other literary detectives. What Simenon introduced that was new in the field of detective fiction was to make his protagonist a quietly spoken observer of human nature, in which the techniques of psychology are focused on the various individuals he encounters – both the guilty and the innocent. Simenon gave his protagonist an almost therapeutic function, in which his job was to make people’s lives better – although that usually involved the tracking down and (sometimes) the punishment of a criminal. Along with this concept of doing some good in society, Simenon decided that Maigret had initially wished to become a doctor but could not afford the necessary fees to achieve this goal. He also had Maigret working early in his career in the vice squad, but with little of the moral disapproval that was the establishment view of prostitution at the time (Madame de Gaulle famously sought – in vain – to have all the brothels in Paris closed down). Maigret, with his eternal sympathy for the victim, saw these women in that light and remained sympathetic, even in the face of dislike and distrust from the girls themselves. In The Cellars of the Majestic/Les Caves du Majestic, the detective has to deal with a prostitute who meets his attempts at understanding with scorn and insults. Whereas modern coppers such as Ian Rankin’s Inspector Rebus are rebellious mavericks, eternally at odds with their superiors and battling such indulgences as alcoholism, Maigret is a classic example of the French bourgeoisie, ensconced in a contented relationship with his wife and less ostentatiously rebellious with authority – although he maintains a maverick sensibility. There is no alcoholism, but rather an appreciation of fine wines – and, of course, a cancer-defying relationship with a pipe (the sizeable pipe collection on his desk rivals Holmes’s violin as a well-known detective accoutrement).

André Gide’s famous encomium mentioned earlier (‘the greatest French novelist of our times’) may overstate the case, but the Maigret books provide us with a detailed picture of French society. There’s social criticism here too – Maigret is always searching for the reasons behind crime, and sympathy is as much one of his qualities as his determination to see justice done.

Guilt and Innocence

Simenon inspired many writers of psychological crime, such as Patricia Highsmith; she once told me at a publisher’s launch party in London that Simenon’s name brightened her mood, whereas my mention of Hitchcock’s film of her first book, Strangers on a Train, definitely did not. Simenon’s early thrillers featured psychological portrayals of loneliness, guilt and innocence that were at once acute and unsettling. The Strangers in the House/Les Inconnus dans la Maison (1940) depicts a recluse whose isolation is shattered by the discovery one night of a dead man in his house. The subsequent investigation draws this former lawyer back into humanity, to take on the case of the murderer himself. The Man Who Watched the Trains Go By/L’Homme qui Regardait Passer les Trains (1938) shows a normal family man, who, when the firm where he works collapses, becomes paranoid and capable of murder. He rushes towards his own extinction, determined for the world to appreciate his criminal genius.

Notions of guilt and innocence are central to the writer’s world view, but rarely in a simple binary sense. Simenon sees the vagaries of human behaviour as complex: he is always ready to condemn egregious examples of malign behaviour, but he is equally ready to demonstrate flexibility when culpable actions can be viewed through a variety of prisms.

Simenon and the Leopard Woman

I was particularly pleased to speak to the much respected publisher and editor Christopher Sinclair-Stevenson, who was something of a triple threat where Simenon was concerned: he had published him, translated him, and visited him in France (as well as hosting his visits to the UK). Christopher was – characteristically – frank regarding his memories of the author.

‘When I was at Hamish Hamilton,’ he told me, ‘the decision was made to republish Georges Simenon. It was, in fact, the writer Piers Paul Read’s father who had made the suggestion. There had been some translations in the UK, but they had not been published with any enthusiasm or care. I was pleased to take up the cudgels, and I was largely left to my own devices – in fact, I was given no instructions at all! I’d read modern languages at Cambridge, and that was clearly qualification enough to publish this prolific Belgian author.

‘Editing and publishing the books should not, theoretically, have been a major task – except that there were so damned many of them. Simenon kept up that amazing flow of work right until the end of his life, but the sheer volume was only part of my problem. There was a certain requirement that was put in place which became known as the “Simenon Rules”. These were not generated by Simenon himself, but by his formidable wife Denyse. She Who Must Be Obeyed made it clear to us – in no uncertain terms – that the translations had to be rendered in English that was exactly the equivalent of the French originals. If I suggested that such a thing was not possible – as any translator will tell you, so much of the job is simply a judgement call as to what is the best approximation in another language – it was met with a frosty response, and this became a major challenge of rendering Simenon into English. We quickly learned that there was no profit in arguing with her, and she was known in our offices as the Leopard Woman, principally because she cultivated these long scarlet nails. Of course, it’s not unusual for an author to hand the difficult jobs of dealing with a publisher to their spouse, who will then make all the draconian complaints, but I’m not sure whether it was him or her that generated these strict edicts.’

I asked Christopher if his impressions of the author were favourable when meeting him. ‘Well,’ he replied, ‘I can’t say that I was greatly enamoured of him in our various encounters. An immensely talented man, of course, but not what I’d call a nice man. My colleague Richard Cobb and I always referred to him as “Le Maître”. But we knew we had to tread carefully regarding such issues as translations, as I mentioned earlier. Retrospectively, I suppose it was surprising that I opted to translate Simenon myself – specifically his novel The Neighbours (Le Déménagement), which was a very bleak piece. But I always admired his non-Maigret novels such as The Man Who Watched the Trains Go By (which was, of course, very successfully filmed). I suppose I got to know him personally best when I visited him in Switzerland. There was a ritual dinner which one had to undergo – largely enjoyable, but with its negative side. There were things I would have to put up with… whether I wanted to or not…’

Christopher hesitated, but I insisted that – after this tempting morsel – he had to expand. He laughed and continued. ‘All right, it was the women. I had to listen at length to the latest in the continuing series of conquests. My job? Simple… listen and nod admiringly at intervals. As the evening wore on and the Calvados flowed freely, he became even franker and I also had to hear the various prejudices that exercised him – everything you would expect, including homophobia. Happily, though, I didn’t have to listen to the usual author complaints about how he was being published in Britain; he was happy with that side of things – happier than his wife, it seemed. Although, interestingly enough, the sales were never strong, although they bubbled over. I think the problem was that he was so damned prolific – I know there were people who assiduously collected every book, but casual readers were never quite sure whether they’d bought a particular Maigret or not. The sales, however, spiked with the television adaptations, which raised the profile of the books.

‘I do have one strange memory of what I think was my final visit to the house in Lausanne. We drank, we talked, and all was companionable – but I was particularly aware that the house seemed ever more like a clinic rather than a comfortable residence. And that, in fact, was what it was. His wife Denyse had begun to show – shall we say – peculiarities? And the house was being prepared for when more medically oriented facilities would be required. It was all very strange – in fact, it was more like a subject for a Simenon novel… A house turning into a sinister clinic. It would have to be sinister in a novel, wouldn’t it?’

MAIGRET’S PARIS

Simenon places Maigret’s office at 36 Quai des Orfèvres, the headquarters of the Parisian judicial police at the Grande Maison, on the banks of the Seine on the Île de la Cité – a place of pilgrimage for the Simenon enthusiast. Venturing inside the building, it is still possible to see the famous 148 steps that Maigret ascended to his office. The cast iron stove and worn linoleum that Simenon described are not to be found, but looking through the windows one can see the boats that Maigret gazed upon, still moving slowly down the Seine.

Rue de Douai to Les Gobelins

The Man Who Watched the Trains Go By/L’Homme qui Regardait Passer les Trains (1938) is virtually a travelogue of Paris, as the protagonist wanders aimlessly around from district to district, sleeping with (but not having sex with) a variety of prostitutes. The novel contains an evocative – and very Parisian – image of an elderly woman selling flowers in the Rue de Douai (an image not impossible to conjure up in modern-day Paris), but it also features a vividly rendered trip to a neighbourhood at the opposite end of town – Les Gobelins – which Maigret finds one of the ‘saddest sections of Paris’, with wide avenues of depressing flats laid out like army barracks and cafés crowded with ‘mediocre people’ who are neither rich nor poor.

Pigalle’s Prostitutes and the Gare de l’Est

Maigret,in 1934, was originally planned as the last Maigret novel; by this point Simenon had written six novels in a more ‘literary’ style. In many books, the Pigalle district is where Maigret encounters denizens of the underworld, drug addicts, pimps and prostitutes; and, as described by Simenon, this is a sleazy but curiously attractive area – in fact, it might be said to have been a better class of sleaze in that era, as more downmarket and more sordid distractions have replaced those that Simenon wrote about. Prostitutes still haunt the red light bars, but they seem very unlike those described in the Maigret novels. Similarly, Rue Saint-Denis is much more a tourist hotspot in the twenty-first century than the exotic and atmospheric locale described by Simenon.

Simenon was not above being playful with the conventions of the detective novel – and the identity of the author. In Maigret’s Memoirs/Les Mémoires de Maigret (1950), Maigret talks about meeting a strange young man called ‘Georges Sim’ – not hard to guess who this is – who arrives to study him and his working methods, reproducing them Watson-like, with embellishments, in a series of books. Like Holmes, Maigret ruefully remarks on these embellishments and laments their inaccuracy.

The book features the Gare de l’Est, a location familiar to many visitors and one that always evokes scenes of mobilisation for war for the detective. In contrast, Maigret notes, the Gare de Lyon and the Gare Montparnasse always make him think of people going away on holiday – while the Gare du Nord, the gateway to the industrial and mining regions, prompts thoughts of the harsh struggle people once had for their daily bread.

Maigret in Montmartre and the Bois de Boulogne

Maigret at Picratt’s/Maigret au Picratt’s featured the detective reminiscing about a striptease in Picratt’s nightspot in Montmartre. He remembers the stripper wriggling out of her dress with nothing underneath and standing there ‘as naked as a worm’ – and, as in the American burlesque, ‘the moment she has nothing left on all the lights go out’. The sort of discreet strip act that Simenon described here seems quaintly historical now. One has to travel to Montmartre at very specific times of the day to avoid its tourist trap atmosphere today, but it is not impossible to mentally recapture the world Simenon evokes.

Simenon aficionados should be particularly pleased with Maigret and the Lazy Burglar/Maigret et le Voleur Paresseux (1961), in which Maigret must disobey orders in order to investigate the murder of an unlikely gang member, whose battered corpse is found in the Bois de Boulogne. The novel is a classic example of Simenon’s skill at devising ingenious plots and situations. It features the Palais de Justice (the law court), which is next to the Conciergerie on Île de la Cité at the south corner of Pont au Change. The Conciergerie, which is now a museum, was used as a prison during the French Revolution and was much feared. Prisoners here included Thomas Paine and Mary Antoinette.

From the Bastille to Place des Vosges

The Boulevard Richard-Lenoirfigures in Maigret’s Dead Man/Maigret et Son Mort (1948), in which the detective speculates on the reason for the area’s bad reputation. He talks about its unfortunate proximity to the Bastille (hardly a disincentive for the Parisian visitor these days, of course) and, he continues, the area is surrounded by ‘miserable slummy little streets’. Again, this is not quite as true of the district in the twenty-first century. Maigret notes, however, the friendly atmosphere and the fact that those who live here grow to love it.

Much of Simenon’s Paris has changed since his day, but the beautiful Place des Vosges, however, where Simenon lived, is still very much the area that Simenon evoked, in terms of both its elegant atmosphere and its beauty. At one time, Simenon located his detective’s own home here, although Maigret is more often described as living in the Boulevard Richard-Lenoir. The upmarket art galleries and haute cuisine restaurants still nestle under the historic arches, and – more than in many Parisian locations – it is possible to imagine oneself retracing the footsteps of the author’s pipe-smoking copper. In addition to Maigret and his prolific creator, famous inhabitants of the square have included Victor Hugo and Théophile Gautier.

One striking memory of Simenon may be found at a watering hole close to the Quai des Orfèvres, the Taverne Henri IV (13 Place du Pont Neuf); the owner was, in fact, a friend of the author, and various photographs on the wall show Simenon enjoying himself at this very location.

Throughout the Maigret novels, the visual aspects of the scene are conveyed impeccably, especially the locations. Simenon’s sharp eye for detail is also clearly apparent in his photographic work – as is evidenced by the recent publication of his photographs in The Years with a Leica (with a perceptive introduction by the author William Boyd).

More Maigret’s Paris

I’m not the only traveller who has savoured the City of Lights with Maigret in mind. The writer Andrew Martin, creator of the evocative Jim Stringer Railway Detective novels (and much else), is a fellow flâneur.

‘Paris was always my favourite city,’ Andrew says. ‘But I couldn’t put my finger on why. Then I started to read the Maigret novels of Georges Simenon, and found encapsulated the dreamy, wintry not-trying-too-hard Paris that I loved: zinc-topped bars, blue-jawed toughs drinking from dainty wine glasses, Pont Neuf in the rain, that pre-dinner hour when the lights come on, when everyone is mellow yet galvanised.

‘Simenon hated the word “literature”, but his psychological understanding and sense of place ensured he was rated by many highbrows. The English traveller aiming to “do” Maigret in a day can begin their appreciation by arriving at the Gare du Nord, described in Maigret’s Memoirs/Les Mémoires de Maigret as “the coldest, draftiest and busiest” of Paris’s stations. “In the morning, the first night trains from Belgium and Germany generally contain a few smugglers, a few traffickers, their faces as hard as the daylight seen through the windows.”

‘Taking a metro to the heart of Maigret country, you find the police headquarters at 36 Quai des Orfèvres on the Île de la Cité. This is alongside the now-damaged Notre Dame cathedral, but the true Maigret aficionado would be more interested in the nearby restaurants. In Maigret and the Informer/Maigret et l’Indicateur (among others), Maigret lunches at the Brasserie Dauphine, supposedly on the Rue de Harlay, where he favoured the corner table commanding a view of the river.

‘The Brasserie Dauphine is thought to have been based on a real-life restaurant in the same spot called the Trois Marches, but in a rare lapse by the planners of central Paris, it has been knocked down and replaced by a bank resembling a Barratt home.

‘I visited a restaurant at 13 Place du Pont Neuf, the Taverne Henri IV, where the proprietor, a M. Cointepas, told me that he had been to visit his old customer Simenon in Switzerland shortly before he died in 1989. “He was in a wheelchair, and he couldn’t speak… But he was drinking a beer and smoking a pipe,” he added. M. Cointepas told me that he often retraces the steps taken by Maigret in his investigations, and at home prepares the dishes described in the books as being favoured by the detective, especially blanquette de veau – approximately veal stew. At the time I visited, many senior law enforcers still came into the Taverne at lunchtime – they stood at the bar while the judges sat at the tables. But French detectives no longer drink alcohol during the working day.

‘Walking from the Taverne, I arrived at the Place des Vosges in the Fourth Arrondissement. It is surrounded on all four sides by the seventeenth-century buildings that once formed the palace. Incredibly, these fairy-tale premises served – in the 1930s and 1940s – as apartments for the not very well off, including the young Simenon, who set The Shadow Puppet/L’Ombre Chinoise here, invoking a world of pinched, disappointed people inhabiting gaslit labyrinths. The building now houses apartments for the wealthy, or baronial antique shops, and Ma Bourgogne at 19 Place des Vosges, depicted in Madame Maigret’s Friend/L’Amie de Madame Maigret as a dowdy tabac, had become a sumptuous café/restaurant where steak frites were particularly pricey.

‘As dusk fell on my Maigret odyssey, I headed for Montmartre, especially the compellingly sleazy vicinity of Boulevard de Clichy. In Maigret’s Memoirs/Les Mémoires de Maigret, Simenon wrote “the prostitute on Boulevard de Clichy and the inspector watching her both have bad shoes and aching feet after walking up and down kilometres of pavement”. In The Shadow Puppet/L’Ombre Chinoise, a girl works as a nude dancer at the Moulin Bleu, which is of course based on the Moulin Rouge, the world’s most famous strip joint, on Boulevard de Clichy. Simenon once described its wide, dark entrance patrolled by tough-looking men in overcoats, as like “the open maw of a monster”.

‘There is much red light activity in the Maigret novels, and to sample (or perhaps, we should say, observe) the real-life equivalent, one could walk down the Rue Fontaine and peak at the half-clothed women in the small cave-like bars. This street is the haunt of the murdered pimp, Maurice Marcia, in Maigret and the Informer/Maigret et l’Indicateur.

‘And to complete my expedition, there was only one option: La Coupole at 102 Boulevard du Montparnasse – not so much because of Maigret, but because of his creator Simenon, who frequented the place in his earlier years, when he was starting work at four in the morning and conducting an affair in the evenings with that exotic temptress and cabaret star Josephine Baker, whom he described as having “the most famous bottom in the world”.’

WRITERS ON SIMENON

A Critic’s View

One of my happiest associations as a freelance writer for hire was with the then literary editor of the Independent newspaper, Boyd Tonkin. It was an association I particularly enjoyed, as Boyd appeared to trust me and very rarely tweaked my reviews before they appeared in the paper. And as – without trying – I had become something of a specialist in crime in translation, I’d put myself in the firing line where Boyd was concerned, as that was very much his area – and remains so. He reminded me recently that he had written about Simenon for The Times, and told me, ‘Simenon’s also in my 100 Best Novels in Translation book – after much deliberation, I chose The Snow Was Dirty, though several others would have done as well.’

‘Inspector Maigret’s last case, Maigret and Monsieur Charles/Maigret et Monsieur Charles (recently translated by Ros Schwartz), ends not with guilt and remorse but with a murderer who “appeared to be very much at ease”. And why not? For the woman who slew a philandering high-society lawyer has finally had the privilege of encountering the clumsy provincial detective who looks into the souls of the wrongdoers he hunts and grants them a kind of absolution. Maigret and Monsieur Charles, which Georges Simenon finished in February 1972, bookends the series of 75 Maigret novels that began, in 1931, with Pietr the Latvian/Pietr-le-Letton. Simenon, though, had no deep-laid plans to do away with his fictional chief of the Paris crime squad. On 18 September 1972, he sat down to plan a new non-Maigret novel – Victor – with his usual ritual of sketching outlines on a manila envelope. Nothing came. He abandoned the idea, and then his phenomenal career in fiction. “I no longer needed to put myself in the skin of everyone I met,” his memoirs record. “I was free at last.”

‘The Liège-born Simenon never went in for half-measures. The 75 Maigret mysteries (although Simenon’s hawk-eyed biographer Patrick Marnham tallies them at 76) stand alongside 117 “serious” novels, mostly psychological thrillers in the deepest shades of noir, and the 200-odd pulp potboilers of his torrentially productive youth. Then, of course, there are the 10,000 women he once claimed (in an interview with his chum Federico Fellini) to have slept with [as mentioned earlier]; his second wife later revised the estimate down to 1,200. Beyond dispute, his books had sold over 500 million copies by his death in 1989.

‘Maigret was born in 1929, in the Dutch port of Delfzijl, on Simenon’s boat the Ostrogoth