16,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Crowood

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

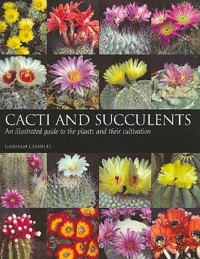

Beautifully illustrated and highly accessible, this essential guide to cacti and other succulents is both a practical manual and a source of reference and inspiration for all enthusiasts. More than 250 different species or genera, and their natural habitats are described. Topics covered include: The unique nature of succulents The natural environment History, classification and nomenclature Watering, feeding, general care and propagation Pests and diseases Profiles of cacti and other succulents

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 341

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Ähnliche

Cacti and Succulents

Graham Charles

First published in 2003 by The Crowood Press Ltd Ramsbury, Marlborough Wiltshire SN8 2HR

www.crowood.com

This e-book first published in 2014

Paperback edition 2006 This impression 2013 © Graham Charles 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84797 786 1

DedicationTo my wonderful wife Elisabeth for her love and understanding. I have so enjoyed sharing our interest in plants ever since the moment we met.

AcknowledgementsSharing with others is a vital part of any activity and so it is with growing cacti and succulents. I am indebted to all the people over the years who have encouraged me and taught me, my companions on the many visits to see the plants in their habitats and the many I have met who have become my friends. I am particularly grateful to everyone who has helped me with this book by allowing me to photograph their plants or by providing pictures. Here I must make special mention of Tom Jenkins, the British Society’s Chairman, who introduced me to the project and gave me support, advice and pictures, particularly of other succulents. Also my good friend Chris Pugh, whose companionship, growing skills and commercial nursery are a constant inspiration. Another excellent grower is Bryan Goody, the owner of Southfields nursery, who allowed me to photograph some of his wonderful plants for this book. Then there are my generous friends who loaned me their photographs: Derek Bowdery, Eddie Cheetham, Eddie Harries, Tom Jenkins, John Pilbeam, Albert and Daphne Pritchard, Chris Rogerson and Bill Weightman – a big thank you to all of them. Finally, a special thank you to my wife Elisabeth for her support and for proof reading the text.

Photographic AcknowledgementsThe names of picture contributors will be found in the captions. All others are by the author.

Frontispiece: Mature plantings of succulents at the Huntingdon Botanical Gardens, California, USA.

Contents

Preface

1. The Unique Nature of Succulents

2. Succulents in their Natural Habitats

3. Cultivation, Propagation and Display

4. Which Species to Choose – Cacti

Astrophytum,

Columnar Cacti,

Cleistocactus,

Pilosocereus,

Coleocephalocereus,

Copiapoa,

Coryphantha,

Discocactus,

Echinocactus,

Echinocereus,

Echinopsis,

Epiphytic Cacti,

Eriosyce,

Gymnocalycium,

Mammillaria,

Matucana,

Melocactus,

Mexican Treasures,

Opuntia,

Parodia,

Rebutia,

Stenocactus,

Thelocactus,

Uebelmannia

5. Which Species to Choose – Succulents

Agavaceae,

Ascepiadaceae,

Crassulaceae,

Euphorbiaceae,

Liliaceae,

Mesembryanthemaceae,

Miscellaneous Succulents

Appendix I: Where to Buy Plants, Seeds and Books

Appendix II: International Societies and Special Interest Groups

Appendix III: Further Reading and Reference

Appendix IV: Glossary of Terms

Index

Preface

It was just over forty years ago when, as a young boy, some friends of my parents gave me my first cacti. My father was a keen gardener and encouraged me to take an interest in plants. It was not long before my expanding collection took over his greenhouse, ousting his tomato plants. As far as I remember he was philosophical about it and continued to support my interest. We saw an advert for the local branch of what was then the National Cactus and Succulent Society, so he took me to the next meeting and we joined that evening. With the encouragement of the other members my interest grew rapidly and I think it has continued to grow ever since, some would say to obsessive proportions! It is certainly true to say that I have derived great pleasure from the hobby, moving my interest from one plant group to another, one aspect of the hobby to another, meeting kind and genuine people, many of whom have become my friends.

The world is very different for young people today. There are so many exciting things to do that you might think that cultivating something as slow growing as a cactus would not appeal any more, but in fact children still find them fascinating and are a major proportion of the buyers at garden centres. Gardening in general is ever more popular; and conservatories, which are becoming more common than previously, make an ideal environment for many succulents. They fit in with a hectic lifestyle, since they have no objection to being left without water for a while and they don’t grow too quickly, so you can spend time with them when it suits you. When I had a demanding career, I used to find the time in the glasshouse a perfect opportunity to relax – after all, nothing happens quickly in a succulent collection!

My aim in writing this book is to give any reader an insight into what the hobby is really like today. I have tried to explain what makes it so much fun and how satisfying it can be. There are no long, wordy descriptions of the plants, just the features that make each one special and what you need to know to get the best out of them. The illustrations are more informative than any description ever can be. The Latin plant names may be a bit daunting but people soon get used to them. Unfortunately, botanists tend to change the names, so I have used the latest ones and referred to older ones you may still encounter. The advice and recommendations are based on my own experiences and may not always agree with what was written years ago and copied ever since. If you are new to the hobby, then I hope you will find all you need in these pages to get started. If you already have an interest in cacti and succulents, then there will be further stimulus for you here. I have given references to other books and sources of information to enable you to develop your hobby further.

Good growing!

Graham Charles

Stamford, UK 2003

1 The Unique Nature of Succulents

Evolution and Adaptation

What are succulents and how do they differ from other plants? There is no absolute definition of a succulent, it is a case of degree – some plants are extremely succulent and others only slightly. Not everyone agrees and succulent collections often contain plants that are only marginally succulent. It is not just a case of storing water; to be a succulent a plant must have evolved ways to conserve its reserves. Some plants, such as begonias, have stems full of water but they are not succulent since they soon wilt and die in a prolonged drought. Succulence takes a number of forms depending on where the water is stored; for instance, there is leaf succulence where the leaves are enlarged with waterstoring tissues such as is seen in echeveria and mesembryanthemums. These leaves can exhibit modifications to reduce transpirational loss of water such as a covering of hair or a waxy bloom.

Stem succulents have thick stems where the water is stored and this is the strategy of most cacti and euphorbias. Stem succulents such as pachypodiums and some euphorbias have normal leaves that grow when water is available and shed in times of drought. Other succulents store water underground in swollen roots, an effective strategy in extremely arid places. In fact, the big swollen subterranean or surface storage may not be roots at all but an adapted part of the stem, for which the term caudex is often used. By combining different types of succulence a plant can be particularly effective at storing water during periods of prolonged aridity.

Lithops otzeniana, a leaf succulent that mimics the stones amongst which it lives.

Obvious examples of stem succulents are cacti, euphorbias and stapeliads, which usually have green stems because they have taken over the function of photosynthesis from the leaves, which are often absent or greatly reduced. In some cacti such as epiphyllums and schlumbergeras, the stem has become flattened and looks like a leaf. Where true leaves are present, they are shed at times of drought. The stems are usually ribbed or tuberculate to allow for expansion and contraction without damage as water is absorbed or lost. In cultivation, splitting can still occur due to excess water being given, particularly after a long dry period. Spherical or cylindrical stems are the best shapes to minimize surface area for a given volume.

Some leaf succulents like this Haworthia maughanii have evolved windows in the tops of the leaves to allow photosynthesis within.

The caudex of this Euphorbia stellata would be underground in habitat. Photo: Tom Jenkins

A remarkable difference between most succulents and other plants is in the photosynthetic process they use to manufacture sugars. Normal plants have green leaves that contain chlorophyll and this is where photosynthesis takes place. Salts and water from the roots are combined by light energy from the sun with carbon dioxide from the air to make sugars. For this to happen, the carbon dioxide must be able to enter the leaf through pores in the surface called stomata that open during the day. Oxygen, which is produced as a by-product of the process, subsequently escapes through these open stomata. Evaporation of water also takes place through the open stomata, which is no problem to a normal plant since it can be replaced from the roots, but for a succulent this loss would reduce its ability to withstand drought. The solution adopted by most succulents is to open their stomata at night when the evaporation loss will be greatly reduced in the cool night air of their natural habitats. They achieve this by fixing the carbon dioxide taken in at night with organic acids that then break down into carbon dioxide and water during the hours of light to be available for photosynthesis. This adaptation was first observed in a member of the Crassulaceae family and is therefore known as Crassulacean Acid Metabolism (CAM). It is for this reason that greenhouse vents should be left open at night in summer to allow the temperature to drop enough for this process to work effectively, and why many cacti do not grow well when planted in tropical places where the night temperature regularly exceeds 20°C (68°F).

Stem succulents from Africa in the genus euphorbia (centre and left) look a lot like the New World cacti (right), but they do not have areoles, which are only found on cacti.

Many cactus-like euphorbias such as this E. ingens have leaves that are lost during the first dry spell.

The most common confusion is between true cacti and other succulents. What is the difference and how can you tell them apart? It is clear from the above that cacti are one example of succulent plants. The strategy of evolving succulence as a way of coping with long dry periods can be found in many plant families. In some, only a few genera or even a few species are succulent; while in others, all the genera are succulent. The cactus family (Cactaceae) is one of the latter; every cactus is a succulent. So how do you decide if a plant belongs to the cactus family? There is no simple way since plants from other plant families have evolved to cope with the same environmental conditions in the same way as cacti and hence look very like them. In fact, they look so alike that experts can sometimes be fooled so there is no need to be concerned if you have difficulty differentiating them. However, there are a few characteristics that, if taken together, can confirm that a plant belongs to the family Cactaceae. They all have spines, even though in some species they are greatly reduced and difficult to see; and they all have areoles, the structures from which the spines grow. These look rather like pincushions but can be very small and difficult to see in many species.

All cacti are from North and South America although they have been introduced to other continents where they have become naturalized so that they look like they belong there. The reason they are only found naturally in the New World is that they evolved after the landmass that became South America drifted away from Africa (part of Gondwanaland). Later, when South America moved northwards it came close enough to North America to allow cacti to migrate and evolve into the wealth of species found today in Mexico and the USA. Of course if you see plants in cultivation you will not know where they grow naturally so you depend on characteristics you can see. Cacti are most easily confused with the succulent euphorbias from Africa, which through parallel evolution have grown to look very like cacti. Look closely and you will see that euphorbias do not have areoles. Another obvious difference is in the flowers, which are small and usually insignificant in euphorbias but larger in cacti. With practice, the differences become more obvious but there are a few genera of cacti that look very different from the classic image. For instance, the primitive cactus genus pereskia has large leaves, thin stems and flowers that are quite reminiscent of roses, hardly what you would expect for a cactus, but they still have areoles. The various pictures in this book should provide the beginnings of an understanding of this dilemma and experience of cultivating plants will eventually make you wonder why you ever confused them.

Pereskia grandifolia, a true cactus, has large leaves and flowers that look like a rose.

Some cacti like this opuntia have leaves that only appear on the new growth. Note the areoles.

Cacti often have large bright flowers like this Thelocactus heterochromus, which also has prominent areoles from which the spines and flowers grow.

Seedlings of cacti (two trays in foreground) are very like those of other succulents – euphorbia (back left) and hoodia (back right).

Flowering

There is a commonly held perception that cacti do not flower, or that they do so only every seven years. The correct treatment of cacti is widely misunderstood, which might explain why well-grown plants are so rarely seen anywhere other than in specialist collections. All cacti and succulents are flowering plants – as long as their requirements are satisfied then they will flower, sometimes spectacularly, but always beautifully. Other than the correct cultural treatment, the only other criterion for flowering is maturity. Once a plant flowers for the first time it is mature and will flower every year thereafter, so long as the environmental conditions are right. Even in the natural habitat conditions may be unfavourable, for instance, a plant may miss a year with its flowering if there has been no rain. Not all individuals of the same species will flower at the same age; there are slight genetic differences that mean some will reach maturity before others. Rarely, a particular specimen may grow perfectly well, but for some reason will not flower, even though it is older and larger then others of the species that do so reliably. There are a few species that just will not flower in cultivation in northern Europe, either because of insufficient sunlight, or because they need to be extremely large before they are mature. However, they can still be valued for their architectural appearance.

Euphorbias often have small and insignificant flowers. Some species such as E. obesa are dioecious: the female plant is on the left, the male on the right.

Flowers of most cacti are short-lived, sometimes just a few hours, depending on the weather and the species. They are produced from the areoles of the cactus and in species such as some rhipsalis and eriosyce, a single areole can produce a number of flowers, either simultaneously or in succession. The plants lose significantly more water when flowering than they do normally, and sometimes you can see the plant has shrivelled after its blooms have been open on a hot day. Some have evolved the ability to set seeds without actually opening their flowers, a phenomenon called cleistogamy. Frailea, for instance, are small plants that can ill-afford to lose moisture so they will only open their flowers when they are well watered and turgid, otherwise they rely on cleistogamy. This is less of a problem for the many night-flowering cacti whose flowers lose less water in the cool of the night. Healthy plants that are growing well flower the most but there is an interesting exception. If a specimen loses its roots and dehydrates it sometimes produces more flowers than normal, presumably in a last effort to reproduce. A similar effect can be observed when a cutting that is dehydrating before it has rooted unexpectedly flowers, sometimes even when the plant it was cut from has never obliged.

A remarkable phenomenon that you can observe in your glasshouse is the ability of plants of the same species to flower simultaneously. Even if the plants have been obtained from different sources, a large proportion will flower on the same day. Whatever the mechanism for this behaviour, it is remarkably accurate. It can often be observed in habitat as well.

The flower diversity in other succulents is even greater than in cacti, reflecting the floral characteristics of the many plant families to which they belong. These are discussed in Chapter 5.

Many species of matucana have flowers evolved for pollination by humming-birds.

The flowers of Grusonia invicta open in the day for pollination by flying insects such as bees.

Weberbauerocereus longicomus has large white flowers that open at night and smell musty to appeal to bats that pollinate them.

Pollination

Many cacti are self-compatible or self-fertile, which means that a single plant is capable of setting seed, either without any help from a pollinator or by the transfer of its own pollen from stamens to stigma. However, most species are self-incompatible, so the pollen needs to be transferred by an insect, bird or animal from the stamens of a flower on one plant to the stigma of a flower on a different individual of the same species. Some flowers are unselective and are pollinated by a range of creatures, but there are also interesting flowers that have evolved to appeal to specific pollinators. The pollination syndrome was once used to separate genera but in today’s classification a single genus may contain species which have unselective flowers as well as those adapted for a specific pollinator. For instance, mammillaria has a few species, once called cochemiea, which have humming bird flowers and a similar situation occurs in eriosyce.

Discocactus have sweet-smelling, nocturnal flowers with a long narrow tube for pollination by moths.

Flowers that are rotate and open in the day can be pollinated by flying insects, notably bees, flies, wasps or even beetles. The other group of day flowers has evolved to appeal to hummingbirds; and these are usually red, sometimes yellow or green, and unscented. The flowers can be bell-shaped, like some echinocereus and lobivia; tubular, like some cleistocactus and melocactus; or zygomorphic, like schlumbergera.

Night-blooming flowers depend principally on pollination by bats or moths, but the flowers often stay open for some time the following morning, so giving other creatures a chance to contribute to effective pollination. Flowers pollinated by bats are bell- or funnel-shaped, usually pale-coloured inside, with thick fleshy petals to enable the bat to cling on. They have large numbers of stamens with copious pollen, and usually smell unpleasant to humans. The genera with this sort of flower are the large arborescent cerei such as carnegiea, pachycereus and weberbauerocereus. Finally, moth-pollinated flowers are smaller with copious nectar at the base of a very long, thin flower tube into which the moth can extend its proboscis, sometimes to more than 20cm (8in). They have white inner petals, a strong sweet perfume, and can be found in diverse genera such as epiphyllum, pymaeocereus and discocactus.

The Cephalium

An interesting feature of some cacti when they reach flowering maturity is the formation of a special growth used only for flowering. This highly adapted structure is called a cephalium and it takes many different forms. It is mainly the columnar-growing cerei that have cephalia, which appear as a woolly or bristly growth, usually down one side of the stem, and originating from the apex. These sometimes sit in a deep groove and can distort the shape of the stem. A good example of this form is espostoa in which the cephalium can extend for more than 2m (6.5ft) down the stem. Nocturnal flowers appear from the cephalium, followed by the fruits, which are expelled from the cephalium when ripe. Another form, only seen in arrojadoa and stephanocereus, is where the cephalium grows as a clump of bristles in the growing point, and then a normal vegetative shoot grows through it, leaving it behind like a collar. Flowers are then produced from these old cephalia for many years (seepage 73). Finally, there are the terminal cephalia that appear in the growing point of the plant when it matures. Once this begins, the production of normal vegetative areoles ceases, so that only the cephalium grows, as in the genus melocactus.

The cephalium on espostoa can extend from the growing point for more than 2m (6.5ft) down the stem and flowers can be produced anywhere along its length.

Classification and Nomenclature

Unlike many other popular plants, most cacti in cultivation are true species rather than hybrids. The only cacti that have been hybridized to any great extent are epiphyllums (the so-called ‘orchid cacti’), echinopsis and astrophytums. Because of this, plants are usually known by their botanical names rather than a common or cultivar name. This can be daunting for beginners but it is surprising how soon the Latin names become familiar. The Cactaceae family has been divided into around 100 genera, and it is the genus that forms the first name of the plant. Each genus has a number of species belonging to it, and it is the species that forms the second name. Some species have been further divided into sub-species (or varieties, which used to be the preferred division). Perhaps because cacti have little commercial value, their classification was mainly the province of amateurs during the twentieth century when most of the species were discovered and named. This resulted in many minor variants being given their own species name (the so-called ‘splitter’s approach’) to a much greater degree than would be the case in other plant families.

Many Brazilian cerei have cephalia like this Micranthocereus dolichospermaticus, which only grows on isolated rock outcrops.

When the cephalium starts to grow on a melocactus, like this M. bellavistensis, the green part of the body never gets any bigger although the cephalium grows ever taller.

There have been many notable attempts to classify the cactus family over the years, either as a whole or by individual genera. At the end of the nineteenth century, cactus exploration and writing was dominated by Germans, the most famous contemporary publication being Schumann’s monograph Gesamtbeschreibung der Kakteen. The first major work in English, The Cactaceae by Britton and Rose, was published between 1919 and 1923 and remains a landmark in cactus literature, the first edition being beautifully illustrated with colour plates. The most extensive and influential work of the century was Die Cactaceae by Curt Backeberg. Published between 1958 and 1962, Backeberg’s ‘splitter’s’ view became the popular approach for thirty years. This was reinforced by the appearance of his lexicon in 1966 that summarized the contents of Backeberg’s monograph and was translated into English with additions in 1977. This remains the most complete treatment on cacti to this day even though many of the plants that Backeberg accepted are now considered to be synonyms of others.

More recently, botanists have endeavoured to reduce the number of recognized species by combining a number of those originally described into broader concepts of species. This has also happened with genera, which has resulted in the disappearance of familiar and much-loved names such as notocactus, neoporteria and lobivia. The new consensus was arrived at through consultation with specialists around the world, and the results of their deliberations were published in 1999 in the second edition of the Cactaceae Checklist. This process of rationalization, which is still evolving, will culminate in a new English-language cactus lexicon, scheduled for publication in 2004.

Schumann; Britton and Rose; Backeberg and Ritter – authors of the major cactus works of the twentieth century.

It has to be said that this has not been popular with hobbyists who like to have a name for every variant in their collections. A specialist collector could now find that his extensive collection of a genus, which represents dozens of wild populations with corresponding names, is now combined into just two or three species. Similarly, the new genera that are botanically defined now encompass plants that are very different from a collector’s point of view, perhaps including tree-sized species and true miniatures.

The story of the nomenclature and classification of other succulents is similar to that of cacti with most being discovered and described in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The task of producing a comprehensive book about succulents fell to Hermann Jacobsen, curator of Kiel Botanic Gardens in Germany, and author of Handbuch der Sukkulenten Pflanzen published in 1954, followed in 1960 by the Handbook of Succulent Plants, an English-language edition. A lexicon appeared some years later, first in German then in English translation. This summarized and updated the contents of the Handbook, and remains a useful publication today. Published in 2001-3, the six volumes of The Illustrated Handbook of Succulent Plants are a comprehensive and up-to-date treatment covering 9,000 taxa, the only problem being the high cost.

History

Succulents from southern Africa first came to Europe at the beginning of the seventeenth century following the colonization of the region. During the eighteenth century, explorations of the interior yielded a steady stream of new discoveries that reached a peak around the end of the century when large numbers of mesembryanthemums were introduced. The names of the explorers will be familiar to succulent enthusiasts because of the plants they found and those named after them. Francis Masson, working for Kew Gardens, introduced the most living plants of any collector. He wrote and beautifully illustrated Stapeliae Novae. William Burchell spent four years travelling in South Africa during which time he amassed 50,000 botanical specimens. The first reference to lithops may be found in his book Travels in the interior of Southern Africa

Cacti were probably first brought back to Europe from the New World at the beginning of the sixteenth century and they gradually started to appear in accounts and illustrations. They caused much interest because of their peculiar appearance, but unfortunately these early specimens came from the West Indies and were much more difficult to cultivate than those that would be found later. It was not until the end of the seventeenth century that there were enough known species to start to differentiate genera, the first four being cereus, opuntia, pereskia and melocactus. In the middle of the eighteenth century, Linnaeus introduced the idea of plant binomials and applied them to the twenty-two species of cacti he recognized. From the early nineteenth century onwards the number of species in cultivation increased rapidly. This was partly because of the explorations of plant hunters, often working for the European botanical gardens, and also as a result of the development of proper glasshouses.

If the historical aspects of succulents fascinate you, a wonderful and well-illustrated book entitled A History of Succulents by Gordon Rowley provides a comprehensive and entertaining account of all aspects of the subject

Uses

Although the indigenous populations of the natural habitats of cacti and succulents have found many uses for them, there have not been any applications that could be said to make them economically important. There were attempts to use the sap of euphorbia to make rubber and the manufacture of sisal rope from agave leaves is quite a big business, but none of the diverse uses of succulents have ever been important enough to attract much attention from professional botanists. Those that have been involved have worked on them through a personal interest in the plants.

Cacti are represented in ancient pottery, such as that from the early Peruvian civilizations, where alkaloids found in the sap of the San Pedro cactus were of great ritualistic importance. The ceremonial use of peyote in Mexico is also of ancient origin – the collectors removing just the heads so that the plant can regenerate from its tuberous roots. Agave sap has long been used to make pulque, an alcoholic drink that was consumed with peyote in ceremonies. The sap of some agaves can also be fermented to make tequila, a fashionable drink available worldwide.

An early engraving of cacti and succulents published in the Florilegia of De Bry in 1612.

Beneficial drugs have been made from succulents, such as a heart stimulant obtained from the flowers of Selenicereus grandiflorus, and the steroid diosgenin extracted from the caudex of dioscorea for the manufacture of cortisone. Perhaps the best-known aloe is Aloe vera, for which many medicinal properties have been claimed, the sap being an additive to many health products. The sap of other aloes also has medicinal applications such as that of A. arborescens, which can be used to treat burns. The sap of some euphorbias has been used as an ointment.

Cacti and some succulents are used by farmers to make hedges or fences. Cuttings of columnar cacti are placed in a line and when they root they make a very effective fence. Opuntias and agaves are used in a similar way but can become a pest if they spread into the surrounding countryside. The dried stems of some large columnar cacti are suitable for building material. Echinopsis pasacana is used in this way in northern Argentina since there are no trees for the local people to use for making roofs and furniture. The resin from the bark of the dragon tree, Draecena draco, is used in cosmetics and varnishes.

Church doors made from the wood of Echinopsis pasacana in northern Argentina.

Many cactus fruits may be eaten, in fact the fruits of hylocereus can even be found in European supermarkets. Opuntias also produce edible fruits so long as you remove the spines. Other uses for opuntias include cattle fodder, a spineless hybrid having been produced for this purpose; and as a host for the cochineal insect, a sort of scale, which is the source of the dyestuff cochineal, used as a red dye for centuries and in recent years for the manufacture of lipstick.

Choosing Species to Grow

Chapters 4 and 5 describe and illustrate a selection of cacti and succulents which are well suited to cultivation under glass even if some will eventually get too large. The total number of species known exceeds 10,000, so it is not possible to cover such a large range comprehensively in a book like this. The plants included have been chosen either because they are the most attractive of their kind and are currently popular with growers, or they are reasonably easy to obtain either as seed or young plants. Some of the more difficult to cultivate species are included because the challenge of growing them well is part of their attraction. Such a small selection is bound to omit plants which are well worth growing, so there are references to specialist literature, which should be consulted to find information on a wider range of species in the various genera. For full details of this further reading, see Appendix III.

The cacti are organised by the classification published in the 2nd edition of the ‘CITES Cactaceae Checklist’, the most recent attempt to reach an international consensus on the nomenclature of the Cactaceae. Nomenclature from older books may not use the same plant names and some of these old names are still in regular use, so a plant may be found with a different name from that used here. To help avoid confusion, commonly used alternative names are mentioned in the text. A New Cactus Lexicon, based on the same nomenclature as this book, and illustrating most of the 2000 accepted species and subspecies is in preparation and will be published in 2004. It is expected to become the comprehensive reference for identification but will not include other aspects of the hobby such as cultivation. The nomenclature used for the succulents is based on that from the most recent books published on the various families.

Cacti

The cactus pages are organised alphabetically by generic name, except for ‘Columnar Cacti’ which is a selection of popular tall-growing plants from various genera, and ‘Mexican Treasures’ where you will find a collection of choice slow-growing plants.

Other Succulents

The succulent pages are organized by alphabetical order of plant families so that similar plants will be found together, except for ‘Miscellaneous Succulents’, which is a selection of plants from other families.

2 Succulents in their Natural Habitats

All the continents of the world have arid areas and, except those that are completely dry, all have plants adapted to live there. Succulence has evolved in many plant families as a strategy to cope with periods of drought, so succulents can be found in many of these dry places but those of most interest to the collector are from North America, South America and Africa. It is a common belief that these plants are only found in deserts, which are technically places that receive an annual rainfall of less than 25.5cm (10in). Of course, many do live in these places, but succulents can also be found in a range of different types of habitat such as grasslands, forests and high-altitude plains. The annual rainfall of an area is not the only thing that determines whether succulents will flourish. The important thing is when the rainfall occurs and hence how long the dry periods last. If there is regularly no rain for months then plants must adopt a strategy to cope with this, therefore succulents from such places have evolved to store large reserves of water. Those from regions with shorter droughts will need less storage and are therefore often less succulent.

The Sonoran desert near Tucson, Arizona, one of the easiest places to view cacti in habitat.

The climate also determines what other plants grow in a locality. Succulents are not capable of surviving competition from leafy plants that overgrow them, so in an area receiving regular rainfall, these other plants will generally predominate. However, even in these places, succulents can find niches where the competition is less, such as rock outcrops or where the soil is too shallow for the other plants to grow. Examples of this can be found in Brazil where various cacti are found on rock outcrops in the forest, some even adapted to only grow on one type of rock.

Neobuxbaumia make spectacular forests in Mexico. Photo: Derek Bowdery

A particularly interesting habitat adaptation has evolved in cacti that live as epiphytes such as rhipsalis, epiphyllum and schlumbergera. These live on the branches of trees or sometimes rocks in the same way as many orchids. Their roots grow in the leaf litter that accumulates on the branches, simply using the tree as a perch to get nearer the light in dense woodland where the canopy of trees makes the forest floor too dark. Since the cacti that inhabit this ecological niche have no leaves, many species have developed flat leaf-like stems to increase their surface area for photosynthesis in their shady environment. This is particularly apparent in epiphyllum, which means ‘upon a leaf’, referring to the flowers that appear to grow out of leaves.

Yucca brevifolia and ferocactus in the Mojave desert, USA.

Altiplano is the name given to extensive areas of high-altitude plains, located mainly in the tropical regions of the Andes. Approximately 4,000m (13,000ft) above sea level, the altiplano is home to many cacti. Resembling European moorland with no trees, just low bushes, it is extremely cold during winter nights. In this unlikely habitat the cacti keep near to the ground, many developing thickened roots for water storage, whilst others form low hummocks in a similar way to many alpine plants. This strategy enables the plant to enjoy the microclimate near the ground, avoiding the bitter winds that frequently blow over this harsh landscape. Further south, away from the tropics, a comparable habitat can be found at lower altitudes in Patagonia where the plants have made similar adaptations. In some places these plants can be covered with snow for months, hardly what you would expect for cacti, but then there can be long periods of drought when their succulence ensures their survival.

The massive Stenocereus weberi in Oaxaco, Mexico. Photo: Derek Bowdery

Aloe africana and Euphorbia polygona on Robin’s Hill, South Africa. Photo: Daphne Pritchard

The greatest concentration of succulents is found in Africa, particularly southern Africa. Most of the huge number of mesembryanthemums may be found here, including lithops, the famous ‘stone plants’ that look like the rocks among which they grow. Most of the popular euphorbias, aloes, crassulas, stapeliads and other choice genera also come from this region, which may be divided into a number of rainfall zones, both in terms of quantity and season of occurrence, each with its endemic species. In many places succulents are the predominant vegetation although many species are very small and so not immediately obvious, particularly those that have evolved to mimic their surroundings.

Visiting the Plants in their Natural Environments

For the enthusiast, the chance to see these plants in their natural environment is hard to resist. But bear in mind that once you have been, you will never feel quite the same way about your plants in pots again, nor are you likely to be satisfied to go only once. There is always another hill to explore or another plant to find! If you get the opportunity, the easiest regions to visit are the USA, mainly for cacti, and South Africa for succulents. If you go to the right places you are guaranteed to see spectacular succulent landscapes.

Conophytum meyeri on a quartz hill near Uitspanpoort, South Africa. Photo: Chris Rodgerson

Spectacular large clusters of Copiapoa dealbata near the coast in northern Chile.

Echinopsis korethroides, growing at high altitude in northern Argentina, makes large clumps of stems.

In the USA, there are many national parks where the plants have been protected and can be seen in their natural state. Outside the parks, pressure of human activity, particularly ranching, has restricted the plants to a few undisturbed places and the private fenced land should not be visited without permission. Particularly recommended for seeing cacti are Anza Borrego Desert State Park, California; Saguaro National Monument, Tucson, Arizona and Big Bend National Park, Texas. There is plenty to see in these and many other national parks in the south-west USA and there are usually local guide books available to help you identify the plants you see, so for a first experience this a safe and easy way to enjoy a succulent habitat. Another way is to go on a trip organized by a tour company or one of the cactus societies. These are usually quite expensive, but everything is organized for you, so there is no need to worry about car hire, where to stay or where to go to see the plants. This is a particular advantage if you don’t speak the local language.

They look just like saguaros in the Sonoran desert, but these are Echinopsis pasacana growing in northern Argentina.

South Africa is also a comfortable place to visit with good roads and hotels. Much of the land there is privately owned and fenced so you should obtain permission from the owner before entering. Although plenty of books will tell you about good places to look, part of the fun is to search likely places and see what you find. After some practice you get to know what sort of terrain is worth a look, for instance white quartzite areas are often rich in succulents. Even so, plants can be unpredictable and can turn up in unlikely places. Intrepid enthusiasts are still finding new locations for known plants and completely new species. Since so many of the plants from this region are tiny, it is likely that there are more still to find.

For the more adventurous traveller, the country with the greatest concentration of cactus species is Mexico. Here you can find spectacular hillsides covered with forests of huge columnar cacti as well as many of the choicest, most desirable cactus species growing in the wild (see page 115