7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

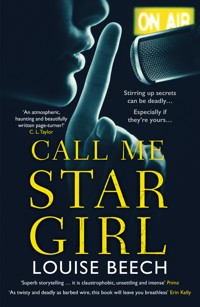

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

A taut, emotive, devastating dark and all-consuming psychological thriller, reminiscent of Play Misty for Me … from the critically acclaimed author of Maria in the Moon and The Lion Tamer Who Lost… ***WINNER of Best magazine's BIG Book of the Year 2019*** ***LONGLISTED for Guardian's NOT THE BOOKER PRIZE*** 'A complex and layered tale that charmed me as a much as it traumatised me. An atmospheric, haunting and beautifully written page turner!' C L Taylor 'Noirish psychological thriller with fascinating, disturbing characters. Compelling, twisty, and seriously addictive. EXCELLENT' Will Dean 'As twisty and deadly as barbed wire, this book will leave you breathless' Erin Kelly _____________ Stirring up secrets can be deadly … especially if they're yours… Pregnant Victoria Valbon was brutally murdered in an alley three weeks ago – and her killer hasn't been caught. Tonight is Stella McKeever's final radio show. The theme is secrets. You tell her yours, and she'll share some of hers. Stella might tell you about Tom, a boyfriend who likes to play games, about the mother who abandoned her, now back after fourteen years. She might tell you about the perfume bottle with the star-shaped stopper, or about her father … What Stella really wants to know is more about the mysterious man calling the station … who says he knows who killed Victoria, and has proof. Tonight is the night for secrets, and Stella wants to know everything… With echoes of the Play Misty for Me, Call Me Star Girl is a taut, emotive and all-consuming psychological thriller that plays on our deepest fears, providing a stark reminder that stirring up dark secrets from the past can be deadly… _______________ 'It's a slow burn at first until it twists and turns at a head-staggering rate to a devastating climax. Original, moody and totally gripping' Claire Allan 'Louise Beech blasts into the world of thriller writing with this moody and tense tale. With secrets, lies and plenty of twisty turns, it's story is dark and it's setting eerie and evocative. Definitely one where you might look over your shoulder more than once while reading!' Fionnuala Kearney 'An original story and beautifully written, so atmospheric … Dark, mesmerising and utterly devastating' SJI Holliday 'Beech has used her unique flair and constructed a crime fiction story that will have you frantically turning the pages until you get to the end' Michael Wood 'It's EXTRAORDINARY – tense, twisted and utterly compelling, written with such raw beauty and unflinching honesty' Miranda Dickinson 'A thriller with heart, passion and twists that will surprise even the most astute readers' John Marrs 'With Call Me Star Girl, Louise proves that she can blow us all away with her writing powers – in whatever genre she chooses' Jack Jordan 'A smart, complex and beautifully written psychological thriller, with a raw intensity at it's heart. Twisty, addictive and completely compelling, this powerful story will keep you hooked and leave you haunted' Best Magazine 'Call Me Star Girl is a unique psychological thriller which is packed with tension and suspense … A dark and atmospheric read which sends shivers down your spine' Irish Independent 'Part psychological thriller, part literary noir and part tragic family drama, its multiple strands slowly merge to reveal a captivating truth' Heat 'MUST READ' Daily Express 'Psychologically unsettling and with a sting in the tail, it's another cracker published by Orenda Books' Russel McLean

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 437

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2019

Ähnliche

Call Me Star Girl

Louise Beech

CONTENTS

This book is dedicated to Granny Kath.When I got pregnant at nineteen you cried because you wanted me to ‘go places’. It took years and years to ‘go someplace’ and get a book deal, but I finally did it.

ALSO

Tyler Benjamin Washbrook-Reynolds12th August 2017–29th August 2017A Star Boy now.

‘Look up at the stars, not down at your feet.’

Stephen Hawking

‘It’s good to have darkness, because when the light comes, it’s that much better.’

Abel Tesfaye (The Weeknd), about his album Starboy

1

STELLA

THEN

Before they found the girl in the alley, I found a book in the foyer at work.

The girl would be found dead, her neck bloody, her body covered with a red coat, and with no obvious clues as to who had left her that way. The book was brand new, unopened, wrapped in brown paper, and had a single clue as to who had left it there.

A note inside the first page:

Stella, this will tell you everything.

After I had picked up the package, unwrapped it carefully and read those words, I looked around the silent radio station, nervous. I’d been about to leave after my show; about to turn off the last light. The nights can be lonely there with just you and the music, and an audience you can’t see. Between songs and commercials, every sound seems to echo along the empty corridors. Every shadow flickers under the cheap fluorescent lights. I don’t scare easily – if anything I love the isolation, the thrill of doing things no one can see – but the book being on that foyer table, where it hadn’t been an hour ago, unnerved me.

Because no one had been in the building since the start of my show.

I looked at the front cover, all smoke greys and silvers; intriguing. The man’s face – half in shadow, half in light – was an interesting one. The eye that was visible was intense – its eyebrow arched, villain-like; and the damp hair was slicked back. The title said Harland: The Man, The Movie, The Madness.

It was Harland Grey. I vaguely remembered the name from news stories. A murderer. Hadn’t he killed a girl on camera, in a movie? Yes. When she disappeared, no one even realised the last scene she filmed had been her death, at the hands of Grey in a cameo as her killer.

I read the blurb, standing alone in the foyer, but it told me little more than I already knew.

What did it mean? Who the hell had left it there?

Why?

Stella, this will tell you everything.

Presenters often receive weird things in the post, but someone had been in the building and delivered this by hand. Tonight. How had they got in? I hadn’t heard the door slam. You need a code to enter the building. Maybe it was just one of the other presenters messing around? But why would they?

The lights buzzed and flickered. I held my breath. Exhaled when they settled. I would not be spooked by a trickster.

Stella, this will tell you everything.

How did they know what I wanted to know?

What was everything?

I opened the main door, book held tight to my hammering chest. The carpark was empty, a weed-logged expanse edged with dying trees. It’s always quiet at this hour of the night. I waited, not sure what I expected to happen – maybe some stranger loitering, hunched over and menacing. They would not scare me.

‘I’m not afraid,’ I said aloud.

Who was I trying to convince?

I set off for home. I usually walk, enjoying the night air after a stuffy studio. I’m not sure why – though now it seems profound – but I paused at the alley that separates the allotment from the Fortune Bingo hall. Bramble bushes tangle there like sweet barbed wire. It’s a long but narrow cut-through that kids ride their bikes too fast along and drunks stagger down when the pub shuts. I rarely walk down there, even though it would make my journey home quicker. The place disturbs me, so I always hurry past, take the long way around, without glancing into the shadows.

I did that night too.

But I looked back. Just once, the strange book pressed against my chest.

It was two weeks before they found the girl there.

Two weeks before I started getting the phone calls.

I didn’t know any of that then. If I had, I might have walked a little faster.

2

STELLA

NOW

People listen to music in their cars, in kitchens, in bed, in the bath, at work, and it takes them somewhere else. A familiar tune might return them to the day they first heard it; to a lover who thrilled them beyond words, to a reunion; to a night when their whole life changed.

I play these songs for people; you could say I play their lives. But tonight is the last time I ever will. It’s my final Stella McKeever Show. I began by telling listeners what they could expect for the next three hours. I didn’t tell them I was leaving though.

Instead I said, ‘Tonight I want to hear your secrets.’

I felt devilish. I felt like having some fun, mixing things up. I imagine that what I said came as a surprise to my listeners. It did to me. My late-night audience usually get a variety of hits from all decades, dull requests and tame discussion.

‘That’s the theme tonight,’ I said, and then I listed all the ways they could contact me. ‘Don’t be shy. I’ll keep it anonymous. But I’d love to talk about all the things we don’t usually mention…’

Now I’m fifteen minutes into the show and I’m restless. No one has been in touch yet. Rihanna’s voice fills the studio. I push my wheeled chair away from the desk, shove the microphone towards the mixer and close my eyes.

My sandwiches have curled already and smell warm; the unappetising odour joins the dusty hum of heat from the equipment. The coffee I bought half an hour ago is so cold its aroma has died.

I’m alone in the WLCR (We Love Community Radio) building. It’s just me until Stephen Sainty arrives before midnight to read the news. I run repeats from his noon bulletin on the hour. Social media means information gets old fast. Community radio can’t compete with up-to-the-minute tweets, though it’s rare our mostly older listeners object to the reheated news. Maybe they like the safety of information that only changes twice a day.

Sometimes I lock the studio door. Most female presenters do on late shifts. They do it to feel safe. I turn the key to put up an impenetrable barrier between the world and me. Gilly Morgan, who does the 3am insomniac slot, said that at least if a killer somehow got in the building he couldn’t get in here because the door is so thick. And by the time he’d figured out a way in, she’d have called the police, her boyfriend, and her mum. Maeve Lynch, the Irish beauty who presents the Late-Night Love Affair between 1 and 3am, said she’d just call the police.

I’d call my boyfriend, Tom.

But tonight, I’ve left the studio door open. What’s supposed to happen will happen. I’m not afraid. If I say it enough, it will be true. I know the girls would say I’m reckless, that there’s a killer out there. They’d say, ‘Think of that poor girl in the alley.’ I am; I have. It’s hard not to when I hear the news every hour, her name every evening. But I’ve always believed that if something’s going to happen it will, lock or no lock.

Someone has been waiting for me after work. For weeks now. Since I found the Harland Grey book but before the girl in the alley was killed. It’s not every night. Usually a Tuesday and a Friday, when I finish just after one. He – it could be a she, I suppose, but it looks like a man – is waiting near the tree in the carpark, hood pulled over head. He pretends to be on his phone, and never looks at me.

The first time, I went back into the building, locked the door and called Tom to come and walk me home. Since then I’ve shouted, ‘I see you there! I’ve got a key that could cut you up a treat!’ Once I cried, ‘Did you get in here, leave me a book?’ But he disappeared.

I’m sure I’ve sensed someone following me home a few times. When I turn there’s no one there. I sometimes think I hear a voice, but strangely it’s soft and not very male-sounding. Stella, it says. Whatare you trying to escape from? Then I refuse to walk faster, to let anyone scare me, even though my feet are itching to run, thrilled that I might be chased.

I shiver.

The cool draught from the open door reminds me of Tom’s breath when he puts an ice cube in his mouth and blows on my skin. I close my eyes, imagine it softly clinking against his teeth, his low curse at the chill, my whispery yes. I run a hand over my neck as though it is his. How easily he wanders into my thoughts. How fast my body responds.

I open my eyes and check emails to distract myself. My heart mimics the drumbeat of the song that’s playing. My hand waits; it knows instinctively where to go when the song dies. I think I’d be able to do my show in the dark. I’d be able to play the reheated news on the hour.

I remember the headlines the night my show first started. A new factory meant hundreds of jobs. Football fans celebrated a big win. Nightclub shut after massive blaze. Police questioned teacher about missing schoolboy. And there were no new leads on the dead girl. It’s been three weeks since they found her in that alley, and still mostly speculation.

I check my phone for messages.

Nothing.

Then I play ‘A Whiter Shade of Pale’ for Buddy because it’s Friday. Buddy is a sixty-two-year-old man who rings every week and requests the song for his wife, Elma. She died six years ago. During one call, he told me they slow-danced for the first time to this song; that he held her so tightly she coughed for five minutes after. They were married thirty-five years.

How do people manage it? What’s their secret? Do they still tear one another’s clothes off?

I slide the microphone fader up and tell the world this one’s for Buddy and his beloved wife. Then I stare at the wall. It’s pale green, chipped where old posters were once tacked, with faded, picture-shaped squares. On a board are photos of Christmas nights out, our trips to the races, interviews with Z-list local celebrities and politicians. I’ve looked at them so many times that our smiles look tired.

I stand, stretch, my socked feet sinking into the carpet. Radio studios need low noise levels and a high standard of acoustic isolation, so the carpet is fat, the walls thick and the ceiling corked. We’re small, can’t afford the best, but we make do; we improvise. A tiny window allows light in during the day, something I rarely see on my shift.

Instead, I’ve only the stars.

Suddenly, the phone illuminates the studio with supernatural sparks. They don’t ring aloud here; they flash blue like tiny immobile police cars. This is in case a listener calls while a presenter is talking live. They ring so infrequently now, once or twice during my three-hour show, that I wonder why anyone bothers muting them at all.

I sit back down and answer the phone. It’s a woman called Chloe. I know her; not in a relationship sense of knowing, but because I spoke to her twice this month and once the previous month. Each time she couldn’t sleep and wanted ‘that song about Van Gogh’. I have six minutes to speak with her before the record and following batch of commercials finish and I must talk to our listeners again.

Tonight she says, ‘I keep thinking about the girl they found in the alley.’

I wonder if she’s going to request a song for her.

‘I suppose people get nervous when things like that happen so close to where they live,’ I say.

‘Maybe.’ Chloe pauses. ‘Makes you scared to go out alone. It was three weeks ago, wasn’t it, but you still wonder if the killer will strike again. Is he biding his time? I carry an alarm with me now and always let my husband know where I’m going.’

‘Understandable,’ I say.

‘They said in the paper that it was personal. How did they know that? Because of stuff we don’t know? And surely murder is always personal? Even a serial killer has feelings about what he does.’

‘Maybe.’

‘I don’t know why your newsreader, that Stephen Thingy, reports the details so coldly,’ she snaps suddenly. ‘He sounds like he’s just talking about the weather or what’s coming up later.’

As well as reading the news, Stephen Sainty runs the station, and he does it closely, often messaging during our shows to tell us what is or isn’t working.

‘I don’t think it’s that he doesn’t care,’ I say. ‘He reads things like that every day. In large doses tragedy is mundane.’ I suppose I sound cold too, but the things we say are not always what we feel. The mouth doesn’t always follow the heart. ‘If he gets too upset he won’t be able to do his job. He won’t be able to be objective and give us the news fairly.’

‘I suppose.’ She doesn’t sound convinced.

‘Did you want me to tell him?’

‘What?’

‘That his tone is cold.’

‘Oh, no, don’t do that. I was only thinking aloud.’

‘“Vincent”?’ I ask her.

‘Sorry?’

‘The song. About Van Gogh. Should I play it?’

‘Yes, please,’ she says. ‘Tonight, play it for the poor girl in the alley. Say you’re playing it for Vicky, because no one says her name like that. They either say her full name or call her thegirl.’

‘And how about your secret?’ I ask.

She pauses.

‘Weren’t you listening earlier?’

She hangs up. I line up her song for later.

I’m not a big talker. Friends ask why I work in radio, and I tell them it’s about listening a lot of the time; listening for the beats, to the tunes, to the in-betweens, with the people, in the dark. Listening to the backing vocals in a song to find clues in those blended words. Listening to and counting the chorus repeats, timing the end of one song and the start of another. Talking on the radio isn’t the same as chatting with friends, family or a boyfriend. Even though I’m entertaining listeners, I’m talking to myself.

Tonight, I imagine locking the studio door and saying aloud all the things that never normally leave my mouth. Tell them, Stella. These words come to me and I’m not even sure they’re mine. I frown. Then I picture shocking our sleepy audience, inciting a barrage of complaints, then someone unplugging the power because I won’t stop. I feel anxious, as if I just might do that. I’ve been anxious for weeks.

So much has happened.

And it’s my last show; they can’t sack me.

There’s too much time during the songs to think. I slide the microphone fader up and tell listeners they can expect the weather sponsored by Graham’s Haemorrhoid Cream in five minutes, followed by a classic from The Beatles, then ‘Vincent’, and that Maeve Lynch will be here later with some songs for all the lovers out there. And in the meantime, if they have anything at all they want to reveal, they can call the usual number.

‘Come on,’ I say, ‘you can tell me anything. You don’t have to give me your name. And just to be fair, I’ll share something no one knows about me every half hour.’ I pause. ‘How about this?’ I pause again. ‘Tonight’s my final show.’ I wait to feel sad about it, but it doesn’t happen. ‘Yes, my very last one; so how about calling in and making it extra special…’

Then I play the music.

I nibble on my warm sandwich but can’t finish it. I should make fresh coffee; there’s time, but I never drink it all. I’ll make a pot before Maeve arrives for the Late-Night Love Affair. I often wonder why love songs are given precedence in a late-night slot. Is romance only for the hard of sleeping, the owls? What if someone is frisky at breakfast? Sentimental at lunch?

I think of Tom again.

He’s never far from my thoughts, like he’s standing behind an open door in my head, ready to leap on me every time I close my eyes. Once, when neither of us could sleep, he asked what I was doing in 1991. I reminded him that I was hardly born, that for some of the year I resided in my mother’s womb, lying crossways, according to her grumble about my stretching her in all the wrong places. Tom lit a cigarette as we talked, and I took a long drag and asked what he was doing in 1991. Why was he interested in that year, since he’d only been two then?

He didn’t answer that question; instead he said he preferred the years with odd endings, like 2007 and 2017. ‘Those seem to be the years that have meant the most,’ he said. ‘When I left home and came here and started university. When I met you.’

I thought about it. ‘Maybe,’ I said. ‘My mum left in 2003. I met her again this year – 2017. A month before I met you.’

‘Odd years, odd stuff,’ he said. ‘Good odd.’

I can listen to Tom talk forever; it means I don’t have to. It means I can lean back, and all my thoughts go to sleep. I’m at peace. If he ever bored me, I don’t know what I’d do. I’m not tired of him yet, but he does scare me sometimes. Is that the thrill of being with him? But how much fear is too much?

The radio never used to bore me. Every shift was different. The commercials were repetitive, like a heartbeat between songs, and they sustained the show. But the music varied; the beats changed. Recently it’s begun to feel samey. Like I’ve run out of words. People have been saying that radio is dying for years, but it’s only the way that people listen that has changed. Thanks to apps and streaming we’re actually more accessible.

Accessible: the thought of that depresses me. I like difficult to reach. Challenging.

The music ends, and I talk about what’s happening on the local roads, about the schedule for tomorrow, and say the next song will be ‘Love Yourself’ by Justin Bieber because no one has asked for it. I could talk about the murdered girl. I could say her name, unlike the tweeters, where she’s #thegirlinthealley. It’s late enough for dark musings, just as it’s late enough for romance.

No one has responded to my open invitation yet, but I know one person will. Because he has called every Friday for the last three weeks, and one random Tuesday.

To tell me he knows who killed Victoria Valbon.

That’s her name.

He might call and tell me everything tonight. His name. How he knows. And who he thinks it was.

For now, I play music I hardly hear because I keep thinking about Tom; about when we first talked about playing dead.

3

STELLA

THEN

My mum once told me I began wrong.

When I was eleven, she lit a cigarette with a jewelled lighter and said I grew transverse in her womb, an elbow nudging her cervix as though to escape early. She said that, when my feet emerged before my head, covered in mucus and blood, she knew I’d be an awkward girl.

When I was twelve she left me with the woman next door. The only thing I had to remember her by was an antique, cut-glass perfume bottle with a star-shaped stopper, and enough perfume inside to let me smell her now and again. She was floral, sweet, gone.

When I was twenty-six she came back.

Eight months ago, we met again.

She was waiting at her window for me, as though she’d been standing there for the last fourteen years, and I simply hadn’t known. Where her hair had lost some of its colour, her eyes remained bright; they flashed blue, like the phones at the studio. The way they always had when I was small. I felt that if I went away for another fourteen years and came back, she would still be standing there, still waiting, and that I’d feel again the buzz of our reunion.

I’ve tried to retain that high since we first met again. I’ve tried to let it carry me. Tried to let it thaw my heart. Replace her perfume.

I did still sometimes carry my mum’s antique bottle with me after we’d met again. I used to unplug the star-shaped stopper when I was alone and let the floral scent fill the air. I wanted to keep her sweet like it was. I wanted to flush away the many questions she hadn’t – and still hasn’t – answered. Ones I haven’t asked because I don’t want to ruin anything.

‘Oh, you still have it,’ she said, when she saw it in my bag during our reunion. ‘All this time, I wondered if you’d keep it.’

She held it in front of her face, the thick glass decorating her cheeks with flecks of rainbow. Her eyes dimmed with an emotion I couldn’t decipher – because I didn’t know her well enough.

‘I thought I’d never see it again.’ She looked at me, perhaps realising she had lost much more than the bottle the day she left. ‘You looked after it all this time?’

‘Have it,’ I whispered.

‘Oh, no, you should keep it.’

I shook my head and said she should take it back.

‘No, it’s yours.’ She touched the intricate stopper.

I shook my head again, more insistent. I had carried it around with me all through school. Some kids had laughed when they found it, threatened to pour it away. I could hear them still, their voices shrill. I was prepared to surrender it now though, now she was back.

‘I want you to keep it,’ she said again. ‘Because…’

‘What?’

‘Nothing,’ she said softly.

We both looked at the bottle.

‘Anyway, in a way I don’t need it … You’re my star girl now.’

‘Am I?’

She had never given me an affectionate name when I was a child. Never called me sweetheart or angel. I wanted to cling to this new name, to bask in her attention. And I also wanted to smash the bottle on the floor.

I laughed instead. ‘Sounds like one of those novels that has “girl” or “wife” or “sister” in the title,’ I said. ‘We just need a killer twist and a cliffhanger ending, and we could have a bestseller called Star Girl.’

‘I didn’t even realise,’ my mum said after a moment.

‘Realise what?’

‘That’s what your name means: star. I read it in some magazine a few months ago. I didn’t know that when I picked it after you were born.’

I knew this already. But I didn’t ruin her words by saying so. I let her talk. I let her in. I try every day now to remember all we said to each other at that reunion. Then I’ll be prepared if she leaves me again.

Floral, sweet, gone.

4

STELLA

WITH TOM

Tom brought up playing dead three weeks ago, the day they found Victoria Valbon in the alley.

The news of her death broke at lunchtime. I was in the garden with the laundry, wondering why the yellow washing line bounced too high for my fingers. Damp clothes hung heavily over my arm – Tom’s underwear, my blouse, our sheets. Hot vapours filled the air, like steam from post-shower-sex bodies. There was something erotic about washing Tom’s clothes, even after ten weeks of living together. Even now I bury my face in his T-shirt when he’s not there, inhale the scent of work and car and sleep and man.

When I was ten, I told my mum I’d never wash a man’s socks; I was adamant I’d be subservient to no one. She said if I loved someone, one day I’d do anything for them. No, I insisted. No, I won’t. But I’ve learned with Tom that if he’ll wash mine, I’ll do anything he asks.

I jumped again to reach the washing line, like a child trying to catch a butterfly. It was like the world had dropped, leaving the line beyond my touch. I loved its distance; the challenge. Finally, I got a chair. Our clothes flapped on the line like those flag markers at a CSI crime scene.

Stephen Sainty’s familiar voice drifted from the kitchen.

Despite what my caller, Chloe, said, I find his tone rich and warm; he delivers misery with beauty. He looks nothing like his voice; most of our presenters don’t. I can’t count the times a listener has come to the studio and said with disappointment that Stephen isn’t what they expected. He sounds like a large furry bear, but he looks like a bulge-eyed frog, his spindly arms as white as new sheets, his hair loose stitching. His voice filled the garden. I always play the radio at home. Antisocial shifts mean daytimes alone. I like my own company, but I need background noise to drown my thoughts.

Stephen said a young woman had been found in a local alley. His voice didn’t waver as he said looks like a savage murder and unidentified and motive not clear. I felt sick when I thought of there being relatives; a family without their girl, not yet knowing they didn’t have her anymore. That gets me every time. It was what every newsreader said on every station and all the TV shows for the rest of the day – a family are going to be utterly bereft.

I know all about families without their girl.

I’ve been that girl.

I went inside, holding the peg bag. On the radio, brutal and policeare baffled and mindless continued. I ran to the sink and threw up green stuff that swirled into the plughole like venom. At least she wouldn’t have to have to pay bills or worry now. She would never be sick.

I waited for more vomit. A knock on the door interrupted my pause. I wiped my mouth and went to answer it. It was our builder wanting payment for some recent roof repairs; he admitted that some tiles had fallen on the washing line and snapped it, so he’d retightened it. Wild ginger hair sprang from a weathered face covered in red freckles.

‘Ah, that’s why.’ I was disappointed at the mundane explanation for my elevated washing line.

‘Why what?’

‘I can’t reach to hang out my clothes.’

He shrugged. There was egg in his ginger beard. I handed him three hundred pounds in twenties. He scribbled a receipt on a headed notepad covered in soil and gave it to me with fat fingers.

‘What am I supposed to do?’ I asked. ‘Get a chair every time I needed to hang laundry?’

He put my money in his back pocket and said, ‘A local girl died, I just heard it in the van – and you’re worried about a length of bloody washing line?’

‘You don’t know me,’ I snapped, and shut the door.

I leaned on it and closed my eyes. He was right. I always worry more about the small stuff, about too-high washing lines, about broken toasters, and getting to appointments late. Life’s greater tragedies – bereavement, childhood abandonment, loss – seem to make my body produce endorphins that blunt its response. Blunt might be the wrong verb. Cushion. Disguise. Protect.

But I always throw up.

I walked around the house, looking, as I had so many times, at our things. Tom is messy; I’m tidy. But we compromise. He leaves the chopping board wildly diagonal, covered in jam and crumbs, a knuckle’s distance from the worktop edge. I prefer it further back so the crumbs don’t fall on the floor – unattainability intrigues me, but I like my inanimate objects within easy reach. Tom and I meet halfway: the chopping board sits a fisted hand’s distance from the edge. But I wash it and put it back straight, while he leaves it crumby. It’s our game. Each of us is briefly right when the chopping board goes our way. Neither of us complains at the other; we each just quietly put it our own way.

It’s the same in all the rooms.

The blood-red sofa in the living room sags where we sit, Tom always on the left, me on the right with my head in his lap. If he’s not here, the four grey cushions sit in a row like prisoners queuing to be executed. If he’s home, they’re on the floor. I love his mess. That he can sit without worrying about disarrayed soft furnishings or wonky picture frames.

It might rub off on me, eventually.

Tom would be home soon; he’d taken a rare afternoon off. I couldn’t wait. I hadn’t yet lost the thrill of his return. Hadn’t yet let him see me looking untidy or undesirable.

We’ve known each other seven months. ‘Known each other’ is an odd set of words. Do people know each other after seven months? After seven years? Seven decades? I hope not; that they might makes me want to sell up and go and live on an island. I don’t want to know Tom. I want there always to be something still to learn.

But I realise one day I’ll know everything, just as he will know everything about me.

Will we cope with it?

When we moved in together I had a special key made for each of us. One of the maintenance men at work was making them, mostly to sell as gifts for people turning twenty-one, but they weren’t selling very well. People had complained they were too sharp, like the edges hadn’t been finished properly. Someone even told me they had slashed their finger open on one. But I felt sorry for him, so I bought two. They’re not the kind of key that opens a door, but a larger version in sterling silver. I had our two initials engraved into them: S and T.

Tom hardly spoke when I gave him his unusual gift. He studied it quietly, his eyes appraising the silver with great seriousness.

‘Thank you,’ he said softly. ‘I love it.’

He attached it to his keyring with all the other keys.

‘I love you,’ he said. ‘I know we’ve only been together nearly four months, but ours isn’t just any four months. Ours is the kind of four months that people write books about.’

The phone rang, disturbing my reverie. I should have known it was my mum. Even though we’d only recently met again, I still felt I knew her; maybe because all the things we’d done separately in between somehow fused us, smoothed out the flaws, allowed space for acceptance. This didn’t mean it was easy – it still doesn’t, even now.

After we got together again she somehow seemed to know when I was thinking of her. I’d look at a picture of us on the computer and she’d text me; or I’d wonder if I should ring her for a change; and then she’d call. This time though I’d been thinking of Tom.

‘I hope you don’t mind,’ she said, like she always does, eternally apologising for being here again after so long away.

‘Why would I mind?’ I switched the kettle on and straightened the chopping board.

‘I’m never sure you’ll be there,’ she said.

‘I am.’ I’m not the one who left, I can’t help but think.

‘I’m going to the shops in a bit. Do you want anything?’

She asks this every time we speak. It touches me deeply because I secretly long for her to take care of me; and it annoys me thoroughly because she should have asked this when I was a kid. Even if I don’t need anything, I tell her that I do. I let her take care of me, so she won’t feel so bad for not having done so since I was twelve. I can’t handle that I might cause her any sadness; it’s hard enough dealing with your own.

‘Get me some eggs if you like,’ I said. ‘I broke mine.’

‘A dozen?’ she asked.

‘Whatever you think.’ A pause then, which I quickly tried to fill. ‘I’m at work tonight. I leave at nine.’

‘Oh, I’ll listen,’ she said, excited as ever about my being ‘famous’.

The radio was how she found me again. She moved back to the area at the beginning of the year. She said she hoped to see me again, somewhere, somehow. And then, one night, she turned on the radio to try to help her sleep.

‘There you were,’ she told me when we met. ‘I knew it was you, even before you said your name. Even after all this time. I was dead proud because you sounded so elegant. So confident. And I knew I was wrong – about what I said when you were small. You aren’t awkward or wilful; you’re strong. You came feet first, so you’d be able to stand on them without me.’

‘Great,’ I said, that afternoon when Victoria Valbon had died.

‘Great.’ Realising she’d mimicked me, she added, ‘Um, okay. I’ll give you the eggs when I see you later this week.’ She paused. ‘I could drop them at yours?’

She has never been to my house. Even though we had been seeing each other again for seven months, I’d never invited her over.

‘It’s okay,’ I said quickly. ‘I’ll get them off you. Tell you what, I’ll pop by in a bit. Yes?’

‘Yes. Did you hear the news? Isn’t it terrible about that poor girl. The one they found in that alley.’

‘I know,’ I said softly.

‘I wonder who she is.’

‘They probably won’t announce it until her family are found.’

‘No. That’s understandable. Well, I should go.’

She hung up.

I wondered for a moment if all relationships could do with a period of separation. They say sex is better after estrangement, too. Tom and I discovered it, of course. Sex. That’s what he said anyway when we first moved in, even though he had a fiancé before we met. I guess every generation of experimental twenty-somethings thinks they discover it; each couple smiles and thinks it was theirs first. But I can’t imagine anyone else ever had a boyfriend suggest something called ‘playing dead’ and didn’t tell him to go to hell.

It was later that day, when Tom had been home for an hour and we’d been in bed a while. His black hair was damp from the shower and his jeans were only part fastened, as though he’d changed his mind halfway. He said, ‘What would it be like if we played a game where you were dead?’

I was thinking that I’d have to get up soon and get ready for work. We’d come upstairs early for sex, and now I had to leave. That’s the only downside to evening work; when others are switching off I must turn on. Tom’s hours are unsociable, too; as a hospital porter, he works all hours, but at least he gets to do days occasionally.

‘What do you mean?’ I asked.

My heart stilled. A game of being dead? We had played many games, ones far sexier than the one with the chopping board. Games of domination with scarves as our handcuffs. Games of pretend where I dressed as a school teacher.

But playing dead?

It felt wrong with a girl just found dead in the alley.

When I was seven I almost drowned. I don’t remember being scared until afterwards, when I scrambled up the slimy river’s edge and was on the shore, dripping toxic liquid into my shit-brown shoes. My mum had reprimanded me for being reckless and began the practicalities of drying a stubborn child who has just escaped death and is trembling with exertion and exhilaration.

I wondered if playing some game of being dead with Tom would prompt the same feelings.

He was watching for my response. He always does when he sets me a challenge. No matter how I feel, I have to play. I love him.

‘It could be me, I suppose,’ he said, as though he hadn’t considered it.

‘You what?’

‘Me who … played dead.’

‘Dead?’ I frowned, still not understanding.

He sat on the bed, mistaking my frown for reluctance, for being afraid and wanting out before we’d begun. ‘I read it in that weird book of yours.’

I followed his gaze to the Harland Grey book on the bedside table. I’d had it two weeks now. I’d shown Tom the curious note inside the cover – whispered the words Stella, this will tell you everything to him – and asked if he had left it at the radio station, even though the handwriting was nothing like his. He had shaken his head, suggested maybe I had a stalker.

I didn’t have much time to read, but I was a few chapters into it then, hoping for clues as to why it had been left for me. Grey had strangled twenty-one-year-old Rebecca March on camera. The moment – in close-up – had featured in the film In Her Eyes and was almost released in the UK. Then he was caught and imprisoned.

I still had no idea why anyone would leave me such a book.

Or what the note meant.

And now, with a girl having been found in an alley dead, I wasn’t sure I would read any more. It was downright creepy to have received it just two weeks before this shocking murder.

‘You’ve been reading it?’ I asked Tom.

‘You seemed so caught up in it – I had to look myself.’

I ran my fingers over his dark, stubbled chin as though to sharpen my senses. ‘Are you sure you didn’t leave it there just so you could suggest weird stuff to me?’ I said evenly, though my heart fluttered inside my chest. ‘And do I need to worry about what you’re doing with those dead bodies at work?’

Tom smiled, shook his head. ‘You know what I love about you, Stella? How brave I can be with you.’

He looked vulnerable then. Sad even. I sometimes think he’s more afraid of his light than his darkness – that he has to keep up the bravado of being adventurous when really he would like to be tender with me.

‘I’d never hurt you,’ he said, ‘but that scene in the book made me think that you being totally out of it during sex would be hot. I don’t know if it’s even a thing. But when I think of you … lying there, as helpless as anyone can be…’ He squeezed my arm. ‘I’m not even saying we should try it, I’m just saying it excites me.’

I didn’t say anything. I loved the thought of exciting him. Keeping him that way. Keeping him. It surpassed any fear of a game called playing dead.

‘How do you think we could play it?’ Tom asked.

He wanted me to answer, so I didn’t. This was how I took over the game.

‘Shall I make us something to eat?’ I suggested.

I hoped he would go on talking. I love Tom’s voice. He can say the ugliest thing and it sounds like something from the Bible or a great poem. When he said play dead it was like he had suggested we eat some exotic food. His mouth follows his heart more than anyone I know.

‘Now I know you’re interested,’ said Tom.

‘And how do you know that?’

‘Because you’re changing the subject.’

‘No,’ I said, getting up. ‘I have to go to work soon and I’m hungry.’

We ate together and listened to the radio and talked about the roof tiles. The reheated news came on at eight and Tom said very softly that the family of the girl in the alley must surely be wondering where she was now, twenty-four hours later.

‘Maybe they’ve been told about the murder now.’ The words caught in my throat. ‘That was just a repeat of the news at noon.’

‘Maybe.’ He paused. I waited. Watched him. ‘I’d know,’ he said.

‘Know what?’ I asked.

‘Know if something had happened to you.’

‘You didn’t know when that weirdo was hanging about near the radio and I had to call you to walk me home.’

‘That just looked like some kid in a hoodie,’ he laughed. ‘You could probably take him.’

‘And what would you do if someone had killed me in an alley?’ I asked softly.

‘Kill them,’ Tom said, without pause.

He held my gaze. His eyes misted. He got up and stood behind me and held me to him until I could barely breathe. I loved it. The intensity of his need. The feeling that he would never, ever abandon me.

Neither of us talked about playing dead again that evening.

Then I went to work and played people’s lives.

5

ELIZABETH

THEN

I was hurting when I had Stella. Not just the way all labouring mothers hurt. Not just because of the contractions and the tearing and stretching. I hurt in my heart. I was angry that I was doing it alone. That the man I loved wasn’t at my side, holding my hand, telling me to breathe slowly and promising me it would all be okay. Even if I’d told him I was pregnant, he wouldn’t have been at the birth. He wasn’t father material.

I wasn’t really mother material either.

And then Stella arrived, all wrong.

The scans had told me she was lying transverse in my womb, but the midwife said I was young, and that I could still deliver normally. Breech deliveries were tricky but possible, she said. Stella’s feet emerged first, so that the worst pain came at the end of her expulsion, not at the beginning, like for most mothers. I screamed as her head completed the journey.

I screamed at the unfairness of it.

Then the midwife put her in my arms and told me she was a girl. I said I already knew. I hadn’t found out her sex, I’d just known. All along. Just as I knew she would change my life. Disrupt it, inconvenience it, bless it. She was a fighter; little red fists pushed open the blanket. She screamed the way I had giving birth to her.

One of my first feelings was disappointment: she was covered in mucus and blood, nothing like the clean, pink babies in films and soap operas.

I called her Stella. I had no names ready. But the next day, in the visitors’ waiting room, a black-and-white movie called Stella Dallas was on the TV. And that was that.

I took Stella home. Part of me wanted to leave her at the hospital. I was sure they would take better care of her than I could. I was young. Alone. This wasn’t what I’d expected my life to be. Only a year ago I’d been nineteen, cutting hair by day and partying at night, with the pick of the men. I’d only wanted one though. I only wanted him. The one who changed everything. The one I could never see again. Stella’s father.

None of my friends came to see me in those early, lonely weeks. They loved me when I was up for clubbing every night, when I styled their hair into glamorous waves before we went out. When I shared the phone numbers of the all men I knew. Once I had a screaming kid, no babysitter and no money, they disappeared. My only companion was frumpy Sandra from next door. She was a retired foster mum who made time to call around when she’d made pies, who fussed over Stella, who could quieten my screechy daughter with just a whisper.

Fuck them, I thought, when my friends didn’t ring.

I washed bottles, changed nappies and tried to smile at my newborn. Tried to meet her never-ending demands. Tried to hide my frustration and sadness. I decided there and then that the best thing I could teach Stella was to be self-sufficient. I could hardly do it by example, but I’d do it the hard way.

As soon as she was a toddler and didn’t need night feeds, I found a part-time hairdressing job, got frumpy Sandra to babysit for nothing, and started going out once more. Alone. To bars. I was stunning. My figure had sprung back, my hair was golden from days in the garden with Stella, and I wore the same skin-tight dresses I had before my pregnancy, with a slash of my favourite fire-engine-red lipstick.

Men flocked around me again. The simmering resentment at being alone dissolved. I could live on this. It would get me through motherhood. The warmth of this attention helped me get up in a morning to a noisy child who asked questions all day. It helped me do all the things that bored me: the cooking, the washing, the story-reading.

But it didn’t erase the face of the only man I had ever loved.

Stella’s father.

Who she would never know.

I would not share his attention with anyone, not even our child.

She first asked me who he was when she was five and the kids at school had been talking about their daddies. Wanted to know why she didn’t have one. We all have them, I said. Some just don’t stick around. Some don’t need to know they have a child. Some aren’t good men, I thought, even if you love them so much that nothing tastes right and sleep evades you, and sometimes, just for a moment, you think your heart has stopped.

Stella asked again when she was seven. And then eight. Each time, I said that she had a dad; he just was the kind that was better out of her life.

I was that kind of mother too. But here I was anyway. Trying to be something that didn’t come naturally to me. Trying to love a needy child when all I craved was the oblivion of nights with men who showered me with compliments, affection, and gifts.

New man Dave bought me perfume.

He said I never wore any. Asked me why. I said I couldn’t afford it. I didn’t tell him about my favourite scent, hidden away in the drawer. The beautiful cut-glass bottle with a star-shaped stopper that I opened every now and again, just to smell. I wore Dave’s cheap, sickly eau de toilette until I got rid of him for being dull. After that I demanded perfume from every man I dated. Most of the fragrances lasted longer than they did. I hoped that each would drown out the smell of my star perfume, wash away the memories that bottle held.

Stella’s childhood flew by. It was a blur of late nights and late mornings, when I’d wake to find that Stella had made her own breakfast and taken herself to school. The haze was punctuated with occasional shared moments, when I’d style Stella’s hair, paint her nails, give her advice. Frumpy Sandra was a blessing, taking her in when I worked late at the hairdressing salon, and always remembering a treat on her birthday. She sometimes went to Stella’s parents’ evenings when I didn’t and helped pay for school trips when I couldn’t.

Sometimes I felt I hardly knew Stella at all. I’d look into her intense eyes and wonder what went on in her head. Other times I wanted to squash her to me and apologise for all my flaws. But mostly I got by on the wave of love men gave me at night, letting that carry me through the dirty dishes and school reports and head lice and ironing.

Sometimes she looked like him. It wasn’t so much her appearance as something she did. A way she’d move. A turn of the head. And my heart would contract.

I loved Stella.

I did.

I just loved her father more.

6

STELLA

NOW

Sometimes, when I’m in the WLCR studio alone, and I’m off air, I undo my shirt to the waist.

We’re not required to wear a uniform, but I like to dress for my show just as I might for any other job. I have five blouses in various pastel shades. Tonight, I selected pink. No particular reason, other than it was the closest to hand. When I lean back in the chair and unfasten my buttons, slowly, one after the other, it’s not because it’s warm in here – though it can be, with all the equipment – but because it feels bad.

There’s a chance I might be caught in this state of semi-undress.

It makes me smile.

I know Stephen Sainty won’t be here until eleven-thirty, and Maeve won’t be in for the Late-Night Love Affair until just before twelve, but there’s still a chance of being seen by someone. Cleaners turn up at random times, maintenance men come, and presenters sometimes arrive early for their shifts. I imagine them seeing me before I can cover up. There’s something about shocking people that I love.

But that need is missing tonight. Even though I’ve left the studio door open. I don’t care if Stephen arrives early and bursts in, gasping at the sight of my bare chest.

I suddenly want to go home and cry.

Five years of the show and I’m tired. It’s partly why I handed in my notice. But, unless he was listening earlier when I shared this information, Tom doesn’t know. He’s at home, so he may have tuned in. I think he’ll be surprised, which is always good. He has surprised me a lot recently, so maybe it’s my turn.