7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

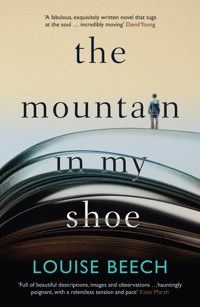

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

After years of abuse, Bernadette makes the decision to leave her husband, only to find that he is missing … along with a little boy she'd befriended years earlier. A tense, dramatic and moving novel from the bestselling author of How To Be Brave and The Lion Tamer Who Lost. 'Full of beautiful descriptions, images and observations … hauntingly poignant, with a relentless tension and pace' Katie Marsh 'Moving, engrossing and richly drawn, this is storytelling in its purest form … mesmerising' Amanda Jennings _______________ A missing boy. A missing book. A missing husband. A woman who must find them all to find herself. On the night Bernadette finally has the courage to tell her domineering husband that she's leaving, he doesn't come home. Neither does Conor, the little boy she's befriended for the past five years. Also missing is his lifebook, the only thing that holds the answers. With the help of Conor's foster mum, Bernadette must face her own past, her husband's secrets and a future she never dared imagine in order to find them all. Exquisitely written and deeply touching, The Mountain in My Shoe is both page-turning psychological suspense and a powerful and emotive examination of the meaning of family … and just how far we're willing to go for the people we love. _______________ 'Deft and full of emotions' Irish Times 'It is a brilliantly creative work of fiction' We Love this Book (The Bookseller) 'A fabulous, exquisitely written novel that tugs at the soul … incredibly moving' David Young 'A moving and powerful book' Jane Lythell 'A rich, psychologically profound novel about overcoming adversity … It's a masterpiece' Gill Paul 'Dark, compelling and highly thought-provoking … a fascinating page-turner that wrenches at your insides' Off-the-Shelf Books 'A wonderful, nuanced book probing the damages wreaked by absence and neglect, while exploring the power of love and hope … and what it means to be truly "home". It made me laugh and cry by turns. I loved it' Melissa Bailey 'An exquisite novel. Darkly compelling emotionally charged. And I LOVED it!' Jane Isaac

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 455

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Ähnliche

The Mountain in My Shoe

Louise Beech

This book is dedicated to my son Conor. Though the character in the story is not you – and not supposed to be you – aspects of you did inspire him, especially you as a child. So I love him the way I do you, and named him after you.

Also to Suzanne, the young girl I befriended while she went through the care system. She came out a survivor, and has a permanent place in my life and heart.

For the late Muhammad Ali.

And Baby P.

‘It isn’t the mountains ahead to climb that wear you out; it’s the pebble in your shoe.’

Muhammad Ali

Contents

1

The Book

10th December 2001

This book is a gift. That’s what it is. A gift because it will one day be your memory. It will soon contain your history. Your pictures. Your life. You. Isn’t it a lovely colour? Softest yellow. Neutral some might say, but I like to think of it as the colour of hope. And I’m hopeful, gosh I am. I hope this book is short because that’s the best kind.

But now – where to begin?

2

Bernadette

The book is missing.

A black gap parts the row of paperbacks, like a breath between thoughts. Bernadette puts two fingers in the space, just to make sure. Only emptiness; no book, and no understanding how it can have vanished when it was there the last time she looked.

The book is a secret. Long ago Bernadette realised that the only way to keep it that way was to put it on a bookshelf. Just as a child tries to blend in with the crowd to escape a school bully, a book spine with no distinct marks will disappear when placed with more colourful ones.

So Bernadette knows absolutely that she put the book in its spot between Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights three days ago, as she has done for the last five years. She peers into the black space and whispers, ‘Not there’, as though the words will make it reappear.

She was waiting by the window when she realised she’d forgotten to pack it; when it occurred to her that the first thing she should have remembered was the last. Bernadette viewed the community of moisture-loving ferns and mosses in the garden below – as she does most nights – and the evergreen leaves had whispered, the book, the book. At the front of the garden, the trees appear to protect the house from the world – or do they protect the world from the house? Bernadette is never sure. She often thinks how sad it is that they must die to become the paperbacks she prefers over electronic reading, and vows then to change her reading habits; but she never does.

She waits in the window every night for her husband, Richard, to return from work. He always arrives at six. He is never late or early; she never needs to reheat his meal or change the time she prepares it. She never has to cover cooling vegetables with an upturned plate or call and ask where he is.

Where on earth is the book?

The thought pulls Bernadette back into the moment. Books don’t get up and jump off shelves; they don’t go into the sunset seeking adventure, with a holdall and passport. It has to be somewhere. It has to be. If she doesn’t find it she can’t leave.

Push away the anxiety and think calm solutions; this is what Bernadette’s mum always says.

Maybe she left it somewhere else. Perhaps the panic of preparing to pack for the first time in ten years had her putting things in the wrong place – a toothbrush in the fridge, milk in the fireplace, her book in the laundry bin. So, just to make sure she hasn’t misplaced it, Bernadette decides to explore the flat.

She starts at the main door. The room closest to it has a fireplace dominating the right wall and this is where she and Richard sleep side by side, him facing the door, her facing the wall his back becomes. Often the distant foghorn sounds on the River Humber, warning of danger in the night. It’s never been replaced by an electronic system and it has Bernadette imagining she’s slipped into some long-gone time when people used candles to walk up the house’s wide stairs. Then she’s happy Richard is at her side; the anxiety his presence often brings is cancelled by her gladness at sharing the vast space of the flat with another person.

Their bedroom enjoys late light from its west-facing window. Richard let Bernadette decorate how she wanted when they moved in and she painted the walls burnt orange to enhance the invading rays.

If she left the book in here it can only be on the bed. Sometimes, when she’s absolutely sure Richard won’t be home, she lies there and reads it. But never has she left it there – and she hasn’t now. It isn’t by the bed or under it or in the bedside table. Searching for it is like when you pretend to show a child there aren’t any monsters in the wardrobe – Bernadette half knows the book won’t be there but she checks anyway.

She goes into the wide corridor of their purpose-built flat. It starts at the main door, ends at the kitchen and tiny bathroom, and looks into three high-ceilinged rooms that their things and her constant attention don’t fill or warm. Last winter’s coldness drove the remaining residents away. Being on a river means the air is damp and the rooms difficult to heat. Low rent attracts people initially. It appealed to Richard. He hates wasting money on unnecessary luxury. It had a roof and walls and doors; it was enough.

Now – with everyone gone – the Victorian mansion called Tower Rise is just theirs. The four other flats are vacant. Their apartment beneath the left tower, with rotting bathroom floorboards and sash windows that rattle when it rains, gives the only light in the building. Cut off from the city and choked dual carriageway by trees and a sloped lawn, soon it will just be Richard’s home.

Tonight Bernadette is leaving.

If she closes her eyes she can picture him parking the car perfectly parallel to the grass and walking without haste into the house. She can see his fine hair bouncing at the slightest movement. Physically Richard is the opposite to his personality; it’s as if he’s wearing the wrong coat. All softness and slowness, pale skin and grey irises and silky hair. With her eyes still shut Bernadette sees him enter the lounge and fold his jacket and put it on the sofa and kiss her cheek without touching it. She imagines her planned words, her bold, foolish, definite words – I’m leaving.

But not without the book.

Bernadette has always been fearful of Richard discovering the one thing she has carefully kept from him for five years. When she got it she knew she would have to hide it from him. Coming home with it that first time on the bus, she wondered how. With its weight numbing her lap, she had noticed a young girl across the aisle; a teen with a brash, don’t-mess-with-me air. A girl in a yellow vest with clear plastic straps designed to support invisibly and make the top look strapless, her breasts pert without help.

It occurred to Bernadette that when you half hide something you draw more attention to it. The straps stood out more than the girl’s pearly eye shadow. The book must go where all books go, Bernadette thought. And so when she got home, that was where it went.

Now she continues her game of prove-the-monster-isn’t-there and looks for it in the second room. She hasn’t been in here for perhaps a month, so what’s the point? It’s empty. The book has never been here. This room she had once hoped would be a nursery and had painted an optimistic daffodil yellow. But children never came. Richard said they had each other. He said that was all they needed.

Bernadette closes the door.

Richard decided the third room should be the lounge. A fraction smaller than the others, it’s easier to heat and the two alcoves are home to his computer desk and Bernadette’s bookshelf. She put their table and chairs by the window so she could look out when they ate. It overlooks the weed-clogged lawn and the gravel drive that leads through arched trees to the river. Over the years, during their evening meal, she has often stared down at the stone cherub collecting water in its grey, cupped hands. A wing broke off years ago and a crack cuts its face in two. Birds gather to drink, their marks staining the grey.

‘We’ll tear that down,’ Richard said when they moved in.

But they never did.

Instead Bernadette filled the lounge with plants in brick-coloured pots, gold candles, dried flowers, homemade cushions, and books. In the window she has read Anna Karenina, and true accounts of survival at sea and travelogues that took her to Brazil and India and Russia.

Still it feels somehow like Richard’s flat. Her choices of wall colour and curtain fabric make little difference because even when he’s not here his presence surrounds her, like when wind rushes down the chimneys sending black dust into rooms and the trees sway together like an army united against some invisible enemy.

Bernadette looks in the desk and under the sofa and through Richard’s magazines. She searches behind the bin and through the cabinet drawers and on the wall shelves. There’s a damp patch near them that no amount of scrubbing will erase. She once said it looked like a streak of blood at a murder scene. Richard shook his head; he always tells her she sees too much in things. She wonders if he will say it tonight when he gets home and finds out she’s leaving. The thought chills her. She’s not brave or brash and doesn’t have a don’t-mess-with-me air. She would never wear see-through straps or pearly eye shadow.

It has taken everything for her to bring herself to leave.

What if Richard doesn’t let her? What if he shuts the door and won’t let her out? What if he talks about locking her away in the dark again? Puts a finger on her lips to shush her? Will he cry when she says she’s going? Will he be sorry? Will he just be angry she ruined his evening?

Bernadette goes back to the bookshelf. She spent a long time this afternoon deciding whether she could carry her many beloved hardbacks and paperbacks out of the door, concluding sadly they were too heavy. She is surprised she didn’t remember to pack the one book that matters most. She can leave the others with Richard, wordy reminders that she once existed – but not the yellow one.

Perhaps if she closes her eyes and opens them again it will appear by magic, like a Christmas gift sneaked into a child’s room while she sleeps. But no, the gap between Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights seems bigger now. She puts fingers between them to check again.

How long has it been gone?

When did she last definitely see it there?

Is it possible she didn’t slide it into its usual spot at all?

3

The Book

Begin at the start is what they say. Begin at the birth is what we’re supposed to do. And I will. But first, welcome to your book.

I’m trying to write as neatly as I can because I’m the first, and also so you’ll be able to read my handwriting – it’s just terrible. Everyone tells me I should have been a doctor (they’re renowned for their bad writing, you see), but I’m not clever enough to cure people and I’d rather help them in other ways.

I’ve only written in one or two of these books so forgive me if I get it wrong. I believe the idea for them started in the USA. Whoever thought it up was just great. I’ve seen adults read the words in pages like these, lost for hours, smiling and crying and finally somehow changed. That’s what these books do – give a chronological account; although I’m already meandering, aren’t I? They’re supposed to help you understand the why and the where and the how and the who – that’s how I like to put it.

Gosh, I should introduce myself, shouldn’t I?

4

Bernadette

Outside, the late-September sun drops behind the trees. The clock reaches six-fifteen. Richard is late. Bernadette frowns at the clock like it might have rushed ahead. He has never been late, not in ten years. No, that’s wrong. There was one time – but she won’t think about it now.

He’s so predictable in his punctuality that she can prepare a meal so he walks through the door and is greeted with the aroma of his favourite beef and herb stew at just the right temperature. She can abandon what she’s doing at five-thirty, cover the table with a white cloth and place on top a napkin folded twice, polished silver knife and fork, and glass of chilled water.

Tonight there is no food. Instead of peeling potatoes and preheating the oven, she packed clothes, toiletries and money into two suitcases she has never used. She cleaned the kitchen and bathroom, and changed the bedding, feeling it wasn’t fair to leave the place dirty. Really she was trying to keep busy. Block the thoughts. The why don’t you just stay? The it would be much easier. The he isn’t going to just say, yes, fine, off you go, Bernadette.

Sometimes – mid chopping onions or polishing the mantelpiece – Bernadette stops and pauses to wonder what she feels exactly. Sad? Happy? Tired? Scared? Angry? Have her emotions run off like a bored husband?

When she and Richard first wed she could list every single emotion. There was pride that this strong, sweetly succinct man wanted to be with her. Excitement when he came home after work. Confidence that giving up a career to be a wife and eventual mother would reward Bernadette as much as it had her mother.

Six-nineteen now. Should she call Richard’s work phone? No, she’ll have to pretend everything is normal and isn’t sure she can. Anyway, the rare times she has called it she got his answering service, an accentless woman who says he’s busy. All she needs to know now is that he’s coming home; it doesn’t matter what the delay is, what has messed up his schedule.

Bernadette doesn’t have a mobile phone. What would be the point? Who would call it? She’s rarely anywhere but Tower Rise and there aren’t many friends who might call to arrange a coffee, no colleagues to discuss work. So Richard can’t leave a message explaining his curious lateness.

Just find the book, she thinks, and you’re ready to leave when he turns up.

Maybe she did pack it after all. Maybe she did it without thinking, just took it from the shelf and walked in a daze to the case. Of course – that’s where it is. She goes to the luggage by the door and rummages, imagining she’ll see the buttery cover, neutral like a blanket for a baby not yet born. But it’s not there. Now an emotion: confusion. And another: fear.

The telephone rings. As though startled, birds flee the treetops in a flap of wings and a shrill of squawks. If it’s Richard with his reasons then she doesn’t want to talk. Let the machine answer, though this will infuriate him. At least she’ll know he’s on his way.

Bernadette’s own soft voice fills the room – We’re sorry we can’t take your call but if you leave a message we’ll ring as soon as we return. We. She always speaks in we; not me or I.

It isn’t Richard – it’s Anne. Anne knows not to call when Richard is there because he doesn’t know about their situation, so for her to ring after six means it must be urgent. Bernadette picks up the receiver.

‘He didn’t come home,’ says Anne, tearful.

For a moment Bernadette wonders how she knows. It isn’t possible. Anne has never met Richard. The women have become close recently and despite not being the most forthcoming person, Bernadette opened up once about her marriage worries. She didn’t share any specifics but admitted she felt isolated at Tower Rise. It was good to share with someone – a someone completely separate.

‘Is he there with you?’ asks Anne.

And now Bernadette realises she doesn’t mean Richard.

She’s talking about Conor.

Conor is missing too? Everything is missing. How is it possible? Perhaps they are all in the most obvious place, like books in a library. But where would that be? If everyone were where they’re supposed to be, Richard would be eating his beef and reading the paper, Conor would be with Anne, Anne wouldn’t be on the end of the telephone, and Bernadette would be measuring out Richard’s ice cream so it has a few minutes to melt slightly.

And the book would be in its designated two-inch slot on the shelf.

‘You’re the first one I’ve called,’ says Anne.

Bernadette takes the phone to the bookshelf and pulls everything off to make sure the no-distinctive-markings book isn’t there, just off centre. Perhaps she is off centre. Perhaps this is a dream, one of those she often has where she’s trying to do a jigsaw and every time she adds a piece the picture changes. What was it Conor said last time, about the centre of the universe being everywhere?

The book isn’t there and Bernadette sinks to the floor. She touches the titles she has read over the years to avoid thinking about her own, about the name she once had, the name Richard then gave her, one she might soon discard. She loved signing her new marital name, once upon a time; the S and W permitted her to swirl and curl the pen with flourish. Richard had smiled at the pages and pages of practice signatures, asking, was she expecting to be famous?

‘Is he there with you?’ repeats Anne, more urgently.

‘No,’ says Bernadette, and Anne’s sobs confirm that she knew this would be the case. ‘What do you mean he didn’t come home?’

Conor is part of the reason Bernadette has finally decided to leave a marriage she has done everything to nourish for a decade. Now he’s missing too. Richard and the book barely matter anymore.

‘You’re stronger than you think,’ Anne said, the time Bernadette opened up. They were in Anne’s kitchen; it was a few months ago but it feels like a lifetime now. They drank tea and waited for Conor, and Bernadette admitted she didn’t know if she loved her husband anymore. Said she wasn’t even sure what love was, but that the thought of anything or anyone else was alien.

I’m not strong, Bernadette thinks now.

That she’s planning to leave her marriage after ten years might make her so. Memoirs about men surviving months adrift at sea define them as strong. People who cope with losing children are definitely strong. But she is just a woman walking away from a man who isn’t what she hoped for. A year ago if anyone had said she’d do it, she’d have said never. A year ago during a phone call home, Bernadette’s mother had asked how things were and she paused a moment, didn’t answer with her customary, ‘Yes, everything’s good.’

Instead she asked her mum, ‘What if everything isn’t good?’

Silence on the other end of the line, and then her mum said, ‘Well, you make the best of it, don’t you? No marriage is perfect and too many people give up these days. My friend Jean from aqua aerobics just left her husband Jim after twenty-five years. She was bored and he’d had a fling. But you work at it, you talk, you do what it takes.’

A year ago Bernadette would have done what it took. Now her belongings are packed in two bags and the flat is as clean as a show home. But without the book or Richard and with Conor now gone, she’s trapped in the house where no one else lives. She can’t play her game of prove-the-monster-isn’t-there anymore.

‘He didn’t turn up,’ says Anne now. ‘And you know that isn’t like him.’

Bernadette pictures Conor last Saturday, closing the door as she departed, the autumn sun bouncing off the glass as though to cut them in two. She had grit in her shoes from the foreshore and he said that when she took them off at home she’d make a mess ‘all over the joint’ and remember him. He said other words she can’t think of now or she’ll cry; ones about mountains and pebbles and Muhammad Ali.

No, Bernadette is not strong. But he is.

‘Can you come?’ asks Anne. ‘If anyone knows Conor, you do.’

The words come out despite Bernadette’s fears. ‘Yes, of course.’

She is afraid that if she opens the front door to leave, all the monsters will jump out.

But she’s going to have to.

5

The Book

So my name is Jim Rogers and I’m your social worker. You might have other social workers through your life. (It all depends how things turn out.) No one can know what will happen when a baby is born in circumstances like yours. By the time you read this you’ll probably know what a social worker is, but I’ll write it in here anyway.

Very simply, social work is about people. Social workers help children and families who are having difficulties. It can be any kind of difficulty – illness, death, emotional problems, circumstances, or other people. We try to do what’s best for all concerned. (Sadly this doesn’t always work.) Occasionally families have to be split up. Usually it’s for a short time but sometimes it can be for much longer. And sadly there are times when it is for always.

I helped decide what was best for you. You were made what is called the subject of a care order, where the local authority has responsibility for you. (I have printed out some information about that and will stick it in your book after this.) We had to decide quickly what would happen and where you would go.

Your mum, Frances, was ill when you were born. She had been ill for a long time. She has an illness that is hard to explain because it’s her head that is poorly not her body. It’s much harder to fix heads. (Sometimes it’s impossible – even for the best doctors.)

Your mum agreed to let you go – not because she doesn’t love you but because she does. That’s what I think, anyway. It often makes it easier for us to help if this happens. She had to let your older brother Sam go too last year. A lovely family took him in and he’s still living there.

We felt you would also be better off living with another family until your mum is well. She couldn’t hold or dress you when you were born because she was too sad. She couldn’t even take you home, even for a short while, so she let someone else take you.

We usually try and put a child with a relative or family friend if we can but in your case it wasn’t possible. You have an Uncle Andrew who wanted to have you, but he has some complicated problems that meant he wasn’t able to.

The next option was short-term care while your mum got help.

Gosh, I must tell you, while I think of it, that she chose your name. I thought you’d like to know that, because names are important aren’t they? Your name means dog lover. It’s nice because your mum said she named you after someone special. I don’t know who it is but I doubt there can be any better name than that.

I can’t tell you anything about your father, sadly. I don’t even know his name. For whatever reason, your mum hasn’t told us who he is. (Maybe she’ll share it with you one day herself. Or maybe later in this book we’ll be able to tell you.) I realise it is hard having only half of the picture, and I’m sorry about that.

So for now you’re staying with a lovely couple called Maureen and Michael. They have looked after lots of babies, sometimes more than one at a time. They have a bedroom where there are four cots, just in case. At the moment two are being used. You sleep in one and a baby called Cheryl Rae sleeps in another.

Maureen and Michael keep pictures of every baby they’ve looked after in a scrapbook. You are the newest. I gave them the first picture of you after you were born. (I’ve also stuck a copy of it at the bottom of this page.)

I was supposed to start with your birth, wasn’t I? Oh well, here goes now. There were no blue or pink blankets on the ward the day you were born so you’re wrapped in lemon in this photo. You were the only splash of yellow next to rows of pink and blue. So we knew who you were right away.

I imagine you want to know what kind of baby you were, don’t you?

Well, the nurse said you were born last thing at night and it had been stormy but then it got very quiet when you arrived. You took so long to cry that the staff thought you were very happy to arrive in the world but then you screamed so loudly they thought you had changed your mind. You were actually due on Bonfire Night but came five days late. But there were still a few fireworks going off somewhere far away.

There’s a copy of your birth certificate over the page so you can see your birthdate, which of course you’ll already know when you read this. But also on there is the name of the hospital you were born in, when and where you were registered, and your mum’s full name.

Your hair was dark and spiky (I stuck some of it in here too, at the top) and your eyes were blue. Most babies have blue eyes at the start. Then, after about six weeks, they can change to brown or green, and the baby’s hair can fall out too. So we will see how you look in a few more months.

Maureen and Michael say you’re always hungry and you sleep well. You like it best when they put your pram under the trees at the end of the garden. The wind in the leaves seems to soothe you.

You’re a good baby, they say. No bother, they say.

They write a small three-page Baby Book for each baby they have. They’re going to photocopy some of yours and I will stick it on another page. So everyone is writing about you.

I’ll be checking on you a lot in these first few months. I’ll visit every week and write all sorts of dull but necessary reports. We have to constantly monitor your life and investigate anything that needs checking and then present whatever we find to the courts. This could last until you’re eighteen, or it might end when your mum is well and you’re living with her again. (We’ll visit her too.)

But this entry in your book is the most important thing I’ll have written this week – much more interesting and special than my other reports.

So, gosh, I suppose it doesn’t really matter what the handwriting is like (as long as you can read it!) or if any of us spell things wrong. It just matters that you have a little piece of your history. When other kids have forgotten their childhoods or been told by their parents that they can’t quite recall those early days you will have it here in black and white, in this book.

And I’m proud to be the first to write in it.

Jim Rogers

6

Bernadette

Bernadette opens the apartment door to leave Tower Rise. Despite repaints, its wood peels as though sunburnt. Fingers on the handle, she realises how similar this feels to when she first entered the place with Richard ten years ago. Her right hand forces the knob roughly anticlockwise – the only way to free the latch – and the other hand dangles by her thigh with two fingers crossed.

What is Bernadette hoping for?

What did she hope for back then?

Richard didn’t follow the tradition of lifting her over the threshold; he carried their luggage instead, letting her be the first to enter their new home. They arrived even before the furniture and Bernadette opened the doors to every room, her icy breath the only thing that filled them. She sniffed the air the way she used to when she was a child and she went somewhere new.

Richard dumped the bags in the corridor, grumbled about the lateness and inefficiency of the removal company, and set about calling them. Bernadette knew he’d soon have the place full of the things family had donated, along with his belongings and her books. She knew he’d make it right; he had so far. So she rubbed her goose-pimpled arms and listened to her new husband’s soft voice telling someone he hadn’t expected not even to have a kettle yet, and she knew she’d soon be warm, because he’d see to that too.

Back then she had expected Richard would always find the kettle; now she knows it’s up to her to find it.

The door hinge squeaks. Bernadette’s fingers are still crossed. A draught from the hall below tickles her ankles. Conor is missing and that’s the main concern. Anne needs her too. For now she can put aside Richard’s rare tardiness and the book’s disappearance, but the thought of Conor not being where he should be is too much. She can either stay here – imprisoned by her old routine – or she can go and help Anne.

Bernadette glances back at her two bags by the lounge door, just like their luggage ten years ago. She’ll return for them. This isn’t the departure she planned yesterday. How can you leave a man who isn’t there? Abandon a ghost that follows wherever you go?

Bernadette closes the door.

Dark stairs lead down to a large hall that she knows was once grand; a local history book she read described polished tiles and ornate double doors, and black-and-white photographs showed fresh flowers on a glass table and family paintings the size of windows. Now an economy bulb barely lights the sparse, dusty area; it flickers like a lighthouse warning boats about rocks.

Outside the taxi Bernadette called has arrived. Bob Fracklehurst – the driver who often takes her to meet Conor – finishes a cigarette and stubs it out in a takeaway coffee cup. He never throws his tab end on her drive, yet she’s seen him do it in other places.

It’s twilight now. The gravel crunches underfoot like spilt crisps. The trees are a black mass, in which Bernadette imagines ghosts and monsters. She gets into the passenger seat, enjoying the blast of warm air-conditioning. Taxis have always taken her to places where more than two buses would otherwise be required. Richard never saw the point in her learning to drive and she agreed that it made no sense; it was costly, and they’d only ever be able to afford one car anyway. While waiting for the children that never arrived Bernadette simply stayed at home, never using her Health and Social Care Diploma to help other families, never travelling to St Petersburg as she’d dreamed of since the age of six, never learning to swim.

‘Usual place?’ asks Bob.

‘Usual place,’ she says.

But tonight it isn’t usual at all.

Having used Top Taxis for five years Bernadette has met most of their drivers. Some she talks to a little, in her shy and agreeable way – most she doesn’t. A driver called Graham is kind and embarrassed about his size and asks thoughtful questions rather than talking over her few words with opinionated ones. Bob lets her daydream. He hums softly and doesn’t badger her with demands for weather talk or a discussion of the local news, chatting only if she begins a conversation.

Then, between, for a smoker, curiously melodic hums, he occasionally enquires about Tower Rise’s history and her husband’s job and her love of reading. Bernadette always relaxes because he reminds her of her father, a gentle man who never raises his voice or hand.

‘This isn’t your normal time,’ Bob says now, and after a thought, ‘or day.’

No, it isn’t. None of this is normal.

Since getting married Bernadette has never been alone in a taxi after six. She has never had anywhere to go at that time that didn’t involve Richard. But for the last five years – two Saturdays a month – she has gone in one from the door of Tower Rise to meet Conor. Saturday is his convenient day and fortunately Richard works six days as a computer engineer so Bernadette can sneak out. The word sneak makes her feel guilty; she does not sneak, she escapes. Just for a few hours.

‘Bob,’ says Bernadette. And then she can’t think of anything.

‘Everything okay?’ he asks her.

‘Not really,’ she admits.

‘Shall I sing and let you be?’

‘I really don’t know,’ says Bernadette.

‘Shall we go?’

Yes, they should. Every minute that passes is one more that Conor might be in some sort of trouble. And what if Richard turns up now? She won’t be able to leave. He’ll demand to know what’s going on and all her planned words for why she’s going have changed now. Now there are only three – Conor is missing – and Richard doesn’t know about him.

‘Please, yes,’ Bernadette says, and the car pulls away.

They drive under an umbrella of trees, where leaves and bark are gloomy faces watching them escape. What if Richard’s headlights now illuminate the evening? Will she tell Bob to put his foot down? Will she open the window and tell Richard she’ll explain everything later? What would infuriate him more – her leaving without telling him, or her telling him she’s leaving?

She won’t wait and find out.

7

The Book

28th November 2002

My name is Maureen and I’ve been looking after you for a full year.

Jim Rogers said I could write a letter that you’ll one day be able to read and I was so very pleased because I never get to talk to any of the babies after they are gone. Not all our babies have a book like yours because most are going back to live with their mummies. Their mummies just need a break and yours did too, but she still does and so you’ll go and live with a foster carer now.

I saw the first part of your care plan and it made me so very sad. There were different options for your future and just one had to be ticked. Someone had ticked the box that said Eventual Return to Birth Family (Within Unspecified Months). At least it wasn’t the other box, Permanent Placement with Foster Carer until Eighteen.

So you may go and live with your mummy again in the future.

I really do hope so.

We were very sad when you had to leave us, but you see we only take babies up to a year old. Sometimes I think I’m too emotional to keep saying goodbye to babies but I love it so much when they arrive. Every time one of you leaves we wish we could have you for longer. I try and imagine how you’ll turn out. They have those really clever computers nowadays that can age you, like when kids go missing and they need to show what they might look like when they’re older. I wish we could do that with all the photos of our babies. All we have is a book of pictures of them when they’re small.

I think you will be a very curious child. By that I mean I think you’ll be into everything. I don’t mean you’ll be odd and weird! Though maybe you’ll be that too in a so very unique way.

You were walking at ten months, which is early, and we just couldn’t keep up! You got into the plants and the washing machine and even into the street a few times. My neighbour Charmaine brought you back one day when you’d got out the cat flap, so we have to keep it locked now. I could never turn my back for a minute.

But your smile lit up the house. I’ll so miss that toothy grin and how you ran away every time I tried to catch you. You were rough with the other babies sometimes. I don’t think you meant to be. You were just hugging them. Like you were grabbing onto them so they couldn’t get away.

I’ve sent your favourite dungarees with you. I loved you in those. They were the only clothes sturdy enough to last for all your adventures! And I also sent the stuffed black cat you like so much. It came with a baby called Ben. He never seemed bothered about it, but you were. You walked around with its nose clamped between your teeth!

You’re so very brave. You didn’t even cry when they took you from us, but I did. I always cry a bit when the babies go but I try and wait until they’ve left. I cried as you stared out of the car window and your blue eyes seemed to forgive me. As if you knew I’d have kept you in a flash if I could. I would. God I would. But it doesn’t work like that.

I hope you’re happy wherever you are. I hope they treat you well and warm your milk to room temperature. It upsets you when it’s too cold. I hope Jim passes all that stuff on to whoever has you and I hope he tells them loud, sudden noises scare you and that you like that TV advert for home insurance with the singing phone.

I miss you so very much already.

I’ll never wash your gooey red handprint off my wall.

Love

Maureen xxx

PS – Here’s a page I’ve copied from the Baby Book we did for you. The rest got ruined, I’m afraid, when milk got spilt on it.

MY BABY – A record of your baby’s milestones

Early Developments

Recognises mother at – Not applicable

Recognises father at – Not applicable

Turns head to one side – Birth

Eyes follow moving object – 3 weeks

First smile – 5 weeks

Laughs out loud – 6 weeks

Plays with hands – 10 weeks

Sleeps all night – 3 months

Eats solid food – 4 months

Notices strangers – 2 months

Sits unsupported – 6 months

Crawls – 7 months (like lightning!)

Stands unsupported – 9 months

Walks at – 10 months

Runs at – 11 months

First word – 12 months – said Mo for Maureen and B for Bye.

8

Bernadette

Bernadette glances back at Tower Rise as though she might never see it again, but her view is denied. No residents, so no lights. The building is a shadow. Not like her first sight of it a decade ago when snow brightened every windowsill, tile and archway. An urgent need for work was disguised by December’s white. Christmas lights and tinsel eventually cheered its melancholy corners, until spring revealed the truth – that nothing could save the long-unloved house.

When their furniture finally arrived that first day, and Bernadette and Richard put desks into alcoves and beds into corners, he suggested she bring it to life with her keen eye for colour and charming way of pairing things. She loved his faith in her; yes, she would bring Tower Rise to life for them. She would furnish it with items that hid the damp and enhanced the high ceilings and tall windows.

And one day she would bring it to life the way she really wanted to; with a child.

‘Might take longer,’ says Bob.

‘Sorry – longer?’ Bernadette thinks she must have missed a previous conversation.

‘Longer to get to east Hull. With rush-hour traffic and all.’

Of course – they have only ever travelled when it’s quiet. Conor and Anne live eight miles away. It usually takes twenty minutes to get across town. The first two miles are along the river. Lights twinkle on the opposite shore as though things are so much better there. Bernadette imagines this every time. What lies over the water? What do people in the little villages that line those banks do?

‘I’m concerned about you,’ says Bob, and it touches her. ‘I don’t mean to intrude but we’ve known each other, how long now? A few years. I get a feel for people. You do in this business, with regulars. Barbara in the office said you sounded upset when you called. Not like yourself.’

‘I’m okay,’ says Bernadette. ‘I will be.’ She pauses. ‘Do you think coincidence is more than mere chance?’

The day’s strange occurrences feel linked; two people and one book missing, within hours. She supposes how she met Richard was such a twist of fate, as the tired cliché goes.

Bob chuckles. ‘I don’t know, but my wife would have plenty to say about it. She always says – what is it now – oh, yes: coincidence is the universe’s way of giving you clues that you’re on the right track. Quite spiritual is my Trish.’

Clues. Did Bernadette miss any? Were there signs that Richard wouldn’t come home? She thinks back to that morning. It was just like any other; he couldn’t have guessed from her actions that she planned to leave. If he was aware he didn’t show it as he went about his morning ritual – shower, shave, shirt.

While he was in the half-tiled corner bathroom, added to the flat as an afterthought, Bernadette ironed his white shirt and considered leaving while he was at work. She paused with the iron mid-air as she thought of it. She could write a note and simply go. Leave it on the table where he’d look for his dinner. Steal down the stairs like a refugee, get Bob Fracklehurst to drop her at the train station. Richard would come home and have to vent his frustration at an empty room as she travelled out of his life for good.

Common sense urged her to do the easier thing. But what Conor had said the previous Saturday still rang in her head: it meant she had to tell her husband the truth. Didn’t Richard deserve to hear why she couldn’t stay any longer? Bernadette continued ironing. She would leave with honesty.

Richard had walked back into the living room then, bare-chested and cleanly shaven. ‘Is my shirt ready?’

She studied him, wondering if she would forget him in such detail. No desire stirred now, despite his good skin and a chest covered in golden hair. The physique that once excited her now left her cold; the opaque eyes that only coloured in rage were dim. He was handsome and would probably age well. But she wouldn’t be there to see it. The thought was odd. Picturing a future without him was difficult, if only because she’d always expected him to be there. If Bernadette thought of how he used to bring home a single flower in their early days, she could remember how it felt. How she warmed.

Now, nothing.

Richard was looking at her. ‘Can I have my shirt then?’

‘Yes.’

She stood the iron upright and handed him the crisp garment. He liked it done well, the pleats ironed with precision, the collar stiff. Not displeased, he fastened it before the mirror. He smoothed down his hair in the way she knew he would. Despite the softness of the strands, there was a part that always refused to flatten and today was the same. He wet and combed it in vain.

‘Here, let me,’ she said.

Grunting, he did. She knew he was in an obliging mood as she applied mousse to the rebellious strands and made them respond to her wishes.

‘How do you do it?’ he demanded, talkative for once.

Don’t be nice, she thought. Don’t remind me of the man you can be – just sometimes – because I’ve fallen out of love with the one you mostly are.

‘I can never manage. A woman’s touch, I suppose.’ He went to the computer desk and gathered his things. ‘I’ll be on time tonight,’ he said, unnecessarily.

Was that a clue? Did he state the obvious? In drawing attention to his usual prompt homecoming was he trying to deceive, like a secret book among the others?

‘What will you do today?’ he asked.

Bernadette paused while folding the ironing board. Did he know her intention? He never asked what she did all day.

Then she saw him packing his laptop without a glance her way and knew he hadn’t expected an answer – he was merely making conversation, was not genuinely interested. She didn’t suppose it mattered much to him what she did all day, as long as she was here to greet him on his return. At the start of their marriage she’d done it because she wanted to. Now she did it because it was easier.

Today I will be leaving you, she thought as she watched him search for some elusive item in a drawer. Today I’ll wander this flat for the last time, counting the minutes until you come home, and I tell you that I don’t feel anything anymore. Today I’m going to pack the few things I brought into this marriage. I’m going to wash the pots and do the cleaning and the clothes. I’m going—

‘See you this evening,’ Richard broke into her thoughts.

When he paused before walking to the door and looked into her eyes in a curiously sad way she thought for a strange second he would kiss her mouth. He hasn’t kissed her like a lover for a long time. But he turned and left, his sweet odour lingering on the air afterwards. Relieved, she watched him open the door with hands that could be as cruel as they were graceful. The clink concluding his exit was the last thing to mark that he’d ever been there. It echoed inside her head for some time. She stood with the ironing board at her side for ten minutes.

So what were the clues? His good mood? Letting her tame his hair? The almost kiss? He thought of kissing her, she’s sure. He studied her longer than usual. Why? And where the hell is he tonight?

‘I don’t know if I believe in it though,’ says Bob.

‘In what?’ Bernadette jumps.

‘The universe and all that. Signs.’

They are in the city centre now. Late-night shopping has the pavements still busy. Some stores are already advertising Christmas bargains. It’s not even been Hull Fair yet – the annual travelling fairground that visits the city for a week in October – but already displays of Santa and elves warn shoppers of their imminence. The world seems to want to get everywhere faster.

‘Is it trouble at home?’ Bob asks. ‘Tell me if I’m being nosy. Tell me to bugger off. I’ll hum and you can daydream.’

He never asks much about her marriage. He knows how long they’ve been together and he said once that he thought he knew Richard, asked was he Richard Shaw from Simpletek Solutions? Bernadette said yes. Bob said he’d built a computer system for the taxi firm years ago. Good system – never let them down. He’d left his card and a few of the lads had used him again, for home computers and such. Bob said he was a bit of a brusque so-and-so but who cares if the work is good?

‘I’m leaving him,’ says Bernadette suddenly. The words jump out like they’re escaping a burning house. She regrets the statement and is glad she said it at the same time.

‘Tonight?’ asks Bob kindly. ‘Without anything?’

‘I had bags ready. But something happened. It’s complicated.’

‘Did he hurt you?’

‘Oh no,’ says Bernadette. ‘Not tonight. I mean – not in the way you mean. No, he’s not violent. I mean, not all the time. Hardly. Only once really.’

‘Once is enough,’ says Bob, gently.

‘I know,’ says Bernadette. ‘But that isn’t…’

‘My daughter had a chap once,’ says Bob. ‘He hit her a few times – it was her fault, she said. She antagonised him, she said. But there’s never an excuse.’ Bob pauses. ‘Sorry. Perhaps I shouldn’t go on. Are you okay?’

Bernadette nods.

‘I only saw him last week,’ says Bob.

‘You did?’ This surprises Bernadette. ‘Richard?’

‘Saturday it was. Did a bit of a guvvy job for me. My lad’s laptop was stuck on this stupid screen. Clicked and clicked but nowt happened. Anyway I called the number on the card Richard left us and he said he wasn’t working and he could pop over there and then because he happened to be in the area.’

‘Which area?’ Bernadette is confused. Richard works on a Saturday, always has. He leaves a little later than on a weekday, just after nine-thirty, but otherwise his routine never wavers.

‘Greatfield Estate,’ says Bob.

This is nowhere near Richard’s office. Perhaps he went at lunchtime. Perhaps he’d gone with colleagues for lunch in a different part of town than usual and so when Bob called he was in the area.

‘Was it lunchtime?’ asks Bernadette.

‘No, early. I was off to football, so he came at ten-thirty. Seemed glad of the cash. Brought his sister.’ Bob slows to allow a gang of kids to cross the road; they jeer and wave beer cans at him. They are only five minutes away from Anne’s house now.

Richard doesn’t have a sister. The city’s shops and theatres and pubs have morphed into council estate houses and Boozebuster off-licences and working men’s clubs. Richard doesn’t have a sister.

‘Are you sure?’ Bernadette asks.

‘About what?’

‘The sister.’

Bob looks like he realises he’s said something not quite right. He sucks in his lips and frowns. Then he opens the window and rummages for a cigarette. ‘I’m sure that’s what he said. Sorry if I’ve put my foot in it. He said she was staying for the weekend. I did think they looked nothing like each other. It’s odd, but you look more like him than she did.’

It was a common observance. Richard said when they met that Bernadette reminded him of his mother. Most women would likely find this an insult – and Richard’s mother was certainly not ideal – but Richard meant physically. He said Bernadette’s coppery hair and white-unless-embarrassed skin were just like his mum’s – girlish, innocent and fresh.

‘He doesn’t have a sister, does he?’ says Bob softly.

Bernadette doesn’t speak.

They are near Anne’s street. Teens gather at the chip shop on the corner. What on earth was Richard doing with another woman? Who is she? A colleague? It’s confusion not jealousy that fuels the questions. Does this woman have something to do with his not coming home? Does Bernadette feel better or worse for this new information? Might it be easier if he loves someone else?

Smoke from Bob’s cigarette snakes through the half-open car window.

‘Maybe I do believe in coincidence,’ he says. ‘Tonight’s shift is cover, I wasn’t even meant to be working. Wife’s not happy, says I’m never home, but I’m glad I agreed to do it. Glad I was here tonight. It’s like I should be. Hope everything works out for you.’ He pauses. ‘You’d have got bloody Brad tonight if he wasn’t ill.’

Bernadette smiles at Bob; Brad is a bulbous-nosed ex-drinker who swears at everyone on the road and drives like he’s in a tank.

They are at Anne’s house. Bernadette has never seen it in darkness. The curtains are closed like sleeping eyelids, and the red and yellow and purple border flowers appear grey. Anne opens the door, her face not visible because she’s backlit by the hallway lamp. Yvonne is behind her with a file. Often Conor waits in the window but of course tonight he isn’t in. Bernadette has almost forgotten why she’s here, but now it all comes back.