7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

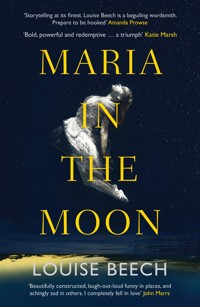

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

A devastating flood reawakens a young woman's buried childhood memories … with life-changing results. A dark, warmly funny and deeply moving novel from the bestselling author of How To Be Brave and The Lion Tamer Who Lost. ***LoveReading Book of the Year*** ***Longlisted for the Not the Booker Prize*** 'Part psychological thriller, part love story and fans of Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine will love it' Red Magazine 'Storytelling at its finest, Louise Beech is a beguiling wordsmith. Prepare to be hooked' Amanda Prowse 'Beautifully constructed, laugh-out-loud funny in places, achingly sad in others, I completely fell in love' John Marrs ______________ 'Like a cold spider, the memory stirred in my head and spun an icy web about my brain. Someone else crawled in. I remembered' Thirty-on-year-old Catherine Hope has a great memory. But she can't remember everything. She can't remember her ninth year. She can't remember when her insomnia started. And she can't remember why everyone stopped calling her Catherine-Maria. With a promiscuous past, and licking her wounds after a painful breakup, Catherine wonders why she resists anything approaching real love. But when she loses her home to the devastating deluge of 2007 and volunteers at Flood Crisis, a devastating memory emerges … and changes everything. Dark, poignant and deeply moving, Maria in the Moon is an examination of the nature of memory and truth, and the defences we build to protect ourselves, when we can no longer hide… ______________ 'Some books seem to fly under the radar and catch you completely by surprise, which is exactly what Louise Beech's Maria in the Moon did. Brilliantly written and incredibly moving, Beech captures the nature of memory and truth with an honest poignancy' CultureFly 'Quirky, darkly comic, but always heartfelt, this original and sad story has wonderful characters and will linger long in your memory' Sunday Mirror 'A powerful and moving story' Madeleine Black 'Heartfelt and wry, this will transport you into a keenly observed world; secrets are hidden, people are flawed, but humanity endures' Ruth Dugdall

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 471

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR LOUISE BEECH

‘Maria in the Moon is storytelling at its finest. Beech is a beguiling wordsmith. Prepare to be hooked’ Amanda Prowse, author of The Art of Hiding

‘Oh, Louise Beech, what have you done to me? Just finished Maria in the Moon and you’ve had me at the brink of tears. Beautifully constructed, laugh-out-loud funny in places, and achingly sad in others. It’s such a beautifully told story of loss and gain. Equal parts Victoria Wood, Alan Bennett and John Irving, all rolled up into an emotive, heart-breaking story. I completely fell in love with it. Thank you’ John Marrs, author of The One

‘Beautiful, poignant, funny, heart-rending, dark – this psychological thriller had me feeling so many different emotions. I was totally enthralled by Catherine and intrigued to find out which memory she had blocked out. This book will stay with me for a very long time. I loved it. Louise Beech is one talented writer!’ Claire Douglas, author of Last Seen Alive

‘In this brave, unsettling book, Louise uses the devastating Hull floods of 2007 as a backdrop to a story of pain and love when horrors from the past rise up. Moving and real’ Vanessa Lafaye, author of At First Light

‘A powerful and moving story about facing buried and difficult memories we would rather forget. Louise Beech is not afraid to tackle challenging but important issues, giving a voice to those stories that are often silenced’ Madeleine Black, author of Unbroken

‘Heartfelt and wry, Maria in the Moon will transport you into a keenly observed world; secrets are hidden, people are flawed, but humanity endures’ Ruth Dugdall, author of My Sister and Other Liars

‘Maria in the Moon is bold, powerful and redemptive. Full of dark humour and poetry, it charts the story of the complex and compelling Catherine, a woman who is constantly helping others in crisis and yet who has no idea how to help herself. The book follows her as she is forced to face up to the truth of something that happened in her childhood – something so traumatic she can’t even remember it. Beech’s skill in depicting human flaws and complexities is evident in every page and the result is a gripping, poetic and beautifully observed story, with the kind of characters I will miss and will still be thinking about in months and years to come. A triumph’ Katie Marsh, author of This Beautiful Life

‘This is a story about how we forget in order to survive, and the price we pay. Catherine is prickly, truculent, and utterly believable. Horrible to her stepmother while yearning for love and approval, stumbling her way through life in a way that’s both too painful to watch and impossible to look away from. It’s not the buried memory that matters so much as the journey of discovery and the impact it has on everyone. This is real life, bruised, torn and coffee-stained, refusing to give up, and finding a way to heal despite all the obstacles. Louise Beech has written a story worth a dozen self-help books; this is showing, not telling’ Su Bristow, author of Sealskin

‘A captivating and haunting exploration of truth, loss and redemption, Maria in the Moon grabbed me from the first page and would not let me go’ Louisa Treger, author of The Lodger

ii‘This is a gorgeous, honest and incredibly moving account of one woman’s journey into a lost and painful past. In prose that’s both raw and lyrical, Louise Beech delicately unpicks her heroine’s tangled history and creates a book I simply couldn’t tear myself away from’ Cassandra Parkin, author of The Winter’s Child

‘In elegant prose, and with a deep affection for her characters, Louise Beech tells a story for our times. Global weather change is the prism – human relations are the focus. Maria and the Moon is in turns tense and affecting … a wonderful piece of storytelling’ Michael J Malone, author of A Suitable Lie

‘Louise Beech effortlessly captures the grind of real life and infuses it with flourishes of subtle poetry to create a wonderful story’ Matt Wesolowski, author of Six Stories

‘Reading a book by Louise is like a visit to the wrong side of the tracks with a friend to hold your hand. As you pick your way through an unfamiliar and unnerving landscape she is forever saying “look – here is beauty; look, there is goodness”’ Richard Littledale, author of The Journey

‘I love the emotional honesty and glorious imagery of Louise Beech’s writing and both are in plentiful supply in this unusual and intriguing story. This is a psychologically complex tale that will provide food for thought long after you finish reading. Highly recommended!’ Gill Paul, author of The Secret Wife

‘Catherine-Maria Hope is a woman with many faces. A face reflected in a cracked mirror creating myriad versions: Catherine, Katrina, Pure Mary, Catherine-Maria; a woman on the edge, in a ripped red dress, circling her past (and the locked-up memory of her ninth year) like an inebriated woman on a dodgy night out. Catherine has been on a few of those. Her memory is pretty good for such occasions and she has the art of self-sabotage honed to within an inch of its life. It is only the year she was nine she can’t remember. From the beginning, this new book from the immaculate Louise Beech has a far darker edge. The air of expectancy is freighted with an undercurrent of something unpleasant and deeply disturbing. Catherine’s voice is fierce and weighted with words she can only half recall. Maria in the Moon is spot on in so many ways. It’s a psychological thriller and a sideways love story. It is impossible not to love Catherine-Maria Hope. In the moon or feet on the ground, being sick in a sink or dancing in a red dress in the rain, she will catch you unawares. After you turn the last page you will still sense her, and the echo of yet another woman’s story: a story of loss and courage and hope. A million stars to enhance the moon’ Carol Lovekin, author of Ghostbird

‘Catherine Hope, the heroine of Louise Beech’s third novel, is a conundrum … Truculent and defensive, yet desperate to be loved, her personality is as inconstant as the names she has taken over the years … But who is Catherine really? She, more than anyone, wants to find the answer to this question, to come to terms with what has been long buried. A dark, wonderful novel of self-discovery, of the things we hide inside ourselves and the bravery it takes to face them’ Melissa Bailey, author of Beyond the Sea

‘Maria in the Moon is the third novel from Louise Beech and by far the best yet. A novel that will test your senses through to the very last page. A dark psychological thriller with complex and damaged characters. So beautifully written, this is a novel that will linger long after you have finished reading’ The Last Word Review

iii‘Louise Beech’s writing is so very powerful, she evokes every emotion in her readers. Yet, despite the heartbreak and damage that Catherine and her family suffer, this author injects her own style of true Northern grit and humour, which is subtly and cleverly interwoven throughout the story. Catherine is not a whimsical, fanciful character; she’s modern, down-to-earth and, as we say here in the North, a bit of a mardy mare. Her relationship and interactions with her mother are a joy to read; strangely familiar to me, and I guess, to many others. Maria in the Moon deals with dark issues that are uncomfortable but necessary. This is superb writing; a story that will stay with me for a long time and is extraordinarily written and presented. There are moments of unexpected beauty from richly complicated characters. It really is quite spellbinding’ Random Things through My Letterbox

‘I wanted to read this book slowly, to savour every moment, yet found myself racing ahead, just to see what had happened to Catherine in the past and what was going to happen to her next. The book is filled with surprises – some good, some bad and some that turned me into a total wreck. All of Louise Beech’s books are different in subject and plot, yet they evoke the same emotions – or rather, all the emotions. I defy anyone to read her books without at least a tear in their eye, although it’s more likely to be a trickle or maybe even a flood’ Off the Shelf Books

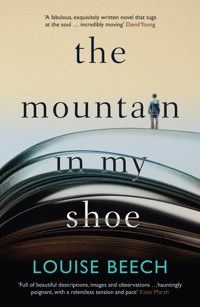

‘Wow! The Mountain in My Shoe has a gentle start but my goodness it packs a punch. I was in tears at the end … a moving and powerful book’ Jane Lythell, author of Woman of the Hour

‘Louise Beech proves with this incredibly moving story that the success of her debut How To Be Brave – a 2015 Guardian Readers’ Pick – was no flash in the pan … A fabulous, exquisitely written novel which will stay with you for a long time after you turn the final page’ David Young, author of Stasi Child

‘This gripping story is the kind of book to put your life on hold for … I was in floods of tears by the end and know that the characters will stay with me for a very long time. A worthy successor to the brilliant How To Be Brave’ Katie Marsh, author of A Life Without You

‘An exquisite novel. Darkly compelling, emotionally charged. And I LOVED it!’ Jane Isaac, author of the DI Will Jackman Series

‘With great compassion for all her characters, Louise Beech deftly creates a story of the survival of life’s sorrows which, with a little help, can lead ultimately to joy’ The Irish Times

‘Beech employs a touch of magic … [How To Be Brave is] … a gentle book, full of emotion, suitable for young readers, and it’s similar in tone to The Book Thief, a book that Rose reads with a torch under the bedclothes’ The Irish Times

‘The Mountain in My Shoe is cleverly laced with a chilling and gripping storyline about a controlling, possibly psychotic husband. I couldn’t put it down. Louise Beech is an author who writers with her heart on her sleeve’ Fleur Smithwick, author of One Little Mistake

‘A fascinating page-turner that wrenches at your insides. It’s dark, compelling and highly thought-provoking and left me with tears rolling down my cheeks’ Off-the-Shelf Books, selecting The Mountain in My Shoe as one of the Top 15 Books of 2016

‘It is a brilliantly creative work of fiction, and a beautiful thank-you letter to the magic of stories and storytelling’ Anna James, We Love this Book

iv‘With lilting, rhythmic prose that never falters How To Be Brave held me from its opening lines … Wonderful’ Amanda Jennings, author of In Her Wake

‘One of the books that has really struck a chord with us this year is How to be Brave by Louise Beech. It is truly 5*, uplifting and compelling. This is a haunting, beautifully written, tenderly told story’ Trip Fiction

‘A wholly engrossing read, How To Be Brave balances its two storylines with a delicate precision. … Bravo!’ Sarah Jasmon, author of The Summer of Secrets

‘A beautiful story full of love, courage and spirit … Louise Beech has cleverly interwoven past and present to produce a brilliant debut novel … I was captivated from the very beginning’ Katy Hogan, author of Out of the Darkness

‘Two family stories of loss and redemption intertwine in a painfully beautiful narrative. This book grabbed me right around my heart and didn’t let go’ Cassandra Parkin

‘An amazing story of hope and survival … a love letter to the power of books and stories’ Nick Quantrill

‘Louise Beech is a natural born storyteller and this is a wonderful story’ Russ Litten

‘This is a yellow brick road of a novel that when it delivers you home will have you seeing all the people you care about anew, in glorious Technicolor’ Live Many Lives

‘…brave, true and utterly compelling, a cliff ’s edge read where you are waiting for that moment then realise that the whole darn thing is THAT moment’ Liz Loves Books

‘Exquisitely written with storytelling of pure beauty … How To Be Brave is a truly unforgettable novel’ Reviewed the Book

‘You’ll instantly connect with the main protagonists and it will leave you feeling completely overwhelmed by how much it has affected you’ Segnalibro

‘Even if you have to beg, steal or borrow, read [How to be Brave] – it is truly spectacular’ Louise Wykes

‘Ms Beech has written an amazing story … of unconditional love, the best cure for every pain and disease’ Chick Cat Library Cat

‘The writing is simply beautiful – quite effortless prose, full of emotion, totally engrossing whichever strand of the story you may be immersed in … Quite wonderful’ Being Anne Reading

‘Prepare for tissues. You would never think that a story of illness merged with a story of sailors abandoned at sea would work, but this does and more. Remarkable.’ The Booktrail

‘Exquisitely written and deeply touching, The Mountain in My Shoe is both a gripping psychological thriller and a powerful and emotive examination of the meaning of family’ The Prime Writers

‘The Mountain in My Shoe is a class act! Highly recommended’ Northern Crime

v‘It was the two beautifully developed characters that drew me in – I felt real warmth and affection for them’ The Very Pink Notebook

‘Louise Beech has the ability to make you care about characters you’ve only known for a few pages, or even paragraphs … Don’t miss this book’ The Misstery

‘Such a captivating book which had me completely involved in the characters’ lives’ Portobello Book Blog

‘The whole book is perfect. A delicately dictated story which intertwines several threads … I highly recommend that you get this bought and read as soon as possible!’ Emma the Little Book Worm

‘Louise Beech writes with such a grace and elegance … It is hard not to be enchanted by her work’ Reflections of a Reader

‘The Mountain in My Shoe … is poignant, profound and perfectly crafted … an absolute must read.’ Bloomin Brilliant Books

‘Beech’s writing is … deeply readable, the kind of book that changes the reader’ Blue Book Balloon

‘In places I could not hold back the tears yet the strength found by the characters to move forward make this an uplifting read’ Never Imitate

‘The Mountain in My Shoe is a beautiful and emotive novel that will leave you wanting more’ The Welsh Librarian

‘The Mountain in My Shoe is just a truly wonderful novel that will melt any heart … I literally could not tear myself away from the story’ By The Letter Book Reviews

‘An astonishing yet humbling book written with a sensitivity that cannot, and will not, fail to move you’ Little Bookness Lane

‘This is a beautifully written, imaginative and profound book … Louise Beech has perfected the art of showing and not telling the reader what is happening’ Short Book and Scribes

‘Louise’s work seems more like tapestry than fiction. Her characters stand out from the page … Every word-stitch has made them more vivid, believable and engaging’ The Preacher’s Blog

‘The Mountain in My Shoe … was heartbreaking and tragic, but also beautiful. Beech writes of this emotive subject with a steady hand … A must read’ The Bandwagon

‘This book is as close to perfection as you’ll ever get … definitely worthy of a 5* rating’ The Book Magnet

‘The author’s writing and narration of Conor’s story is elegant, delicately put across and I found it hauntingly beautiful’ 27 Book Street

‘For me this is a 5* book because of the brilliant way author Louise Beech has of taking the reader right into the heart of the main characters’ Emma B Books

vi‘The Mountain in My Shoe is beautifully told from the outset, the author’s grip of language and hauntingly original metaphor immediately drawing the reader in’ Humanity Hallows

‘Louise Beech writes with an emotional honesty and bravery that elevates her work from the crowd … very highly recommended’ Mumbling About

‘A very cleverly written book’ Needing Escapism, selecting The Mountain in My Shoe as a Top 2016 read

‘The author has an incredible skill of bringing the characters to life and ensuring the reader is truly captivated in every chapter’ Compulsive Readers

‘Simply beautiful. A moving and hopeful 5 stars’ Jen Med’s Book Reviews

‘This book is going to be with me a long time coming!’ Chapter in my Life

‘A story that held drama, some mystery, suspense at the right times, and so much depth of emotions’ Its Book Talk

‘The Mountain in My Shoe is the type of book to bring many different readers together to connect over something so wonderful and magical’ The Suspense is Thrilling Me

‘The Mountain In My Shoe deserves all its hype and much more … I will be recommending this book to everyone’ The Book Review Café

‘A stunning book. I found it incredibly refreshing to read something so beautifully written and emotive’ The Book Whisperer

‘Heart-wrenching at parts, makes you think you know what was going on, but has that twist to show you that you REALLY didn’t know what was coming’ Nutty Reads Reviews

‘The Mountain in My Shoe explores who and what shapes us as people, it’s a story about love in whatever form that may take. A beautiful book’ Woman Reads Books

‘Louise Beech is a fabulous storyteller with a real talent’ If Only I Could Read Faster

‘I cried, I smiled, I laughed, I was frightened, I felt sorry. I lived this story’ Chocolate N Waffles

‘There were twists and heartbreak but also friendship and love in another fantastic and heartwarming novel from Louise Beech’ Steph’s Book Blog

‘If you wish to be moved deeply and taken on a gripping and beautiful exploration of love, loss and the power of emotional connection then I can suggest nothing better’ Shaz’s Book Blog

‘It truly tugged at my heartstrings but all the while balancing that emotion with a promise of hope … This stunning book will stay with me’ My Chestnut Tree Reading

‘Louise is such an emotive writer, you can’t help but get wrapped up in the characters and their lives’ Bibliophile Book Club

‘It is intriguing, deftly crafted and captivating … I have a feeling that I have not read this book for the last time’ Richard Littledale, author of The Littlest Star

‘An absolute joy to read … Louise is a natural storyteller’ My Reading Corner

vii

Maria in the Moon

Louise Beech

ix

This is dedicated to Grace, Claire and Colin. I wrote this one first; and I loved you all first.

x

‘Your memory is a monster; you forget – it doesn’t. It simply files things away. It keeps things for you, or hides things from you – and summons them to your recall with a will of its own. You think you have a memory; but it has you.’

John Irving

‘And love was a forgotten word. Remember?’

Marilyn Monroe

‘Everyone in Hull has a story about that day.’

Suzanne Finn – Hull City of Culture volunteer

Contents

1

Pure Mary

Long ago my beloved Nanny Eve chose my name.

When she called me it in her sing-song voice, I felt as lovely as the shimmering Virgin Mary statue on the bureau in her hallway. When I went for Sunday lunch, I’d sneak away from the table while everyone ate lemon meringue pie and I’d stroke Mary’s vibrant blue dress. Then, listening for adults approaching the door, I’d kiss her peeking-out feet – very carefully so that I didn’t knock her over.

I didn’t want to break her. Not because I knew my mother would send me to bed without supper. Not because I knew I’d be reminded of my clumsiness for weeks after. But because Nanny Eve was given Virgin Mary by her own mother, and she loved it dearly. She would whisper to me that ‘virgin’ meant ‘pure’. Pure Mary. Some of the letters in Mary were like those in my middle name.

But that was all we shared.

She was perfect, whereas I was always in bother. I’d try to imagine how nice it would be to shine so brightly and to not have fingers that got smacked for messing up clean windows. I’d hiss in Pure Mary’s ear that when I got older I’d have a statue in my house and polish her with a special cloth, just like Nanny Eve polished all her special ornaments.

After the Sunday lunch pots had been washed, I’d slip into the living room and sit at Nanny Eve’s feet. She’d always hum the same tune, and I’d know that meant I made her happy. Patting my head, she would say my long, sing-song name, and then she’d get on with her knitting – hats for relatives and coats for my small dolls, and while she did it, she’d tell me about her friends and church and the poor. And then she’d sing 2again, and the sun would break through her lattice window and land on our two curly heads.

But one day she stopped singing.

She stopped calling me the long, pretty name she’d chosen when I arrived.

I try now to remember why, but I just can’t.

I think it was winter; I think the sun no longer had the strength to kiss our heads.

I know I’d accidentally smashed the Virgin Mary.

Utterly unfixable, she had been replaced with a pink plastic lady whose long, spiky eyelashes and crimson lips didn’t call to me. Nanny Eve never polished her.

But there was something else; something I couldn’t remember. Something as black as feverish, temperature-fuelled nightmares. Something that couldn’t be fixed or replaced. Something that stopped all the singing in our house for a long time. But when I try to think of it, all I can see are the shattered porcelain pieces of Pure Mary spread across the floor.

Now I’m the one who chooses the names. I give people longer, different and more quirky ones. Whatever they’re really called doesn’t matter to me. I’ll shorten them, or lengthen them, sometimes switch the letters around, or add a Y. Change them altogether.

Anything that means I’ve taken the word apart and made it whole again. Anything that might help me remember why my name got smashed up with Pure Mary all those years ago.

2

An i causes chaos

‘So which name will you choose?’ he asked.

‘Katrina,’ I said.

‘Katrina?’

I pointed at a faded newspaper on the coffee table – at the headline that read ‘Hurricane Katrina Hits’ and the picture of the devastation it had caused: black, white and grey chaos. The column alongside had a colour picture of Paris Hilton emerging from a car, her silver dress blinking in the flashlights and visible crotch discoloured by a ring of coffee.

‘Good choice,’ said Norman, his eyes still on the stain. ‘Memorable. We’re off to a great start, Katrina.’

In this airless room of telephones, notepads and mismatched chairs, Norman would decide if I could stay; if I could be a volunteer. I imagined other interviewees might feel possessive about their names, might argue that they couldn’t answer to anything else. Our first names are the one constant in our lives, travelling with us wherever we go, stamped in black on our passports and credit cards and driving licences. But I liked the idea of choosing who I could be; of starting anew.

‘We change them so we’re unique,’ Norman said. ‘So we’re easily identified for an urgent call.’

‘Suits me,’ I said, and wanted to add: I rarely call people by their given name.

I’d only known Norman’s for fifteen minutes and wondered why he’d chosen one that evoked a psychotic serial killer. Perhaps his real 4name was in honour of a long-dead relative. He wore a red T-shirt with Sesame Street’s Bert and Ernie on the front; their faces creased when he reached for the file bearing the name everyone calls me. A photo of my sullen face was stapled to the top by my furrowed forehead.

‘I’m the only Norman here so I got to keep my name,’ he said.

So he hadn’t picked it – his parents had, many years before.

‘Some volunteers choose a relative or family pet’s name. Some opt for a film star; although callers might not take a Joaquin too seriously.’

‘Especially if they’re speaking to a female,’ I said.

‘Quite.’ He stirred his coffee and tapped the spoon on the rim of his mug before placing it on the desk, parallel to my folder. ‘We don’t want names to eclipse why we’re here. Take you, Catherine. We already have a Cathryn but she doesn’t have an i in her name. On paper we could differentiate between you, but on the phone – well, imagine the confusion!’ Norman held his hands in the air to animate the chaos my name with its i might cause.

Behind him was a sash window, with one shutter hanging perilously by a single hinge and the other fastened across the glass, giving a half-view of the street: overgrown gardens dusted with snow; fat hedges and fir trees.

‘We also have a Jane who’s the only one,’ he said. ‘Chris number two we call Christopher. Sam is really Sam, but Paul is Al because we had another Paul who left after his leg never healed. You see?’

‘Um, maybe,’ I mumbled.

‘Flood Crisis is about sacrifice,’ he said. ‘And it starts with our names.’

The area behind us looked popular: colourful chairs and beanbags surrounded a centrally placed, stubby Formica table. Much-thumbed magazines covered its scratched surface, and on top a Barbara Cartland novel lay face down, as though she was burying her head in shame at a bad review.

‘So, were you flooded?’ Norman asked. It was the question we all asked one another. It had replaced enquiring after health or families.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Is that why you volunteered?’

5‘No.’

It wasn’t, not really. It was because of a flyer; and a child’s slipper. I’d been buying wine in a supermarket and found a tiny silver shoe in my trolley, utterly at odds with my other items. When I went to hand it in at the customer service desk, the Flood Crisis flyer fluttered into my trolley, landing next to the slipper. The young girl on the desk said, ‘There’s a sign from above if ever I saw one.’

I’d buried it at the bottom of my bag beneath tissues and tampons. But the image of the slipper had kept me awake and had somehow become intertwined with the flyer. Was some child crying for her favourite star-coloured shoe; was she in a strange bedroom after her family home had flooded? Did she wander the new place, one foot cold and bare? Only when I called the number on the Flood Crisis flyer and asked for an interview did I sleep properly again.

Now here I was, ready to volunteer, despite it being only months since I’d walked out of a similar crisis centre. I felt destined to be here; not because I’d been flooded or because I’d done similar work before, and not because of the slipper either; but because of the name-changing.

Norman stopped playing with my folder and put it on top of the others. His fingers tapped the desk. Hands fascinate me; his were as slender as an anorexic woman’s. I looked at my own red-raw fingers and resisted scratching them.

‘Tell me about when you were flooded.’

‘It was crap.’

‘Crap?’ Norman stared at my chest a moment before snapping back to my face.

I should have offered more. I was going to be taking calls from those who’d endured the same downpour, but ‘crap’ was all I had.

None of us had expected the rain. One weather report called it a freak event. Some said it was biblical. Climate change. Punishment. Atonement. Whatever had caused it, at the end of June 2007 it rained for two days. Relentless, like someone had left the taps on full. Water filled gardens, cars and houses. Hull had been labelled the forgotten city. It received the least government help and featured in few 6headlines. But our people came together. We carried one another’s sofas upstairs and shared sandbags, towels and stories.

‘Crap’ was an apt word.

‘Shall I tell you more about us, then?’ Norman asked.

‘Yes, do,’ I said.

I uncrossed my legs and put my bag under the plastic chair. Interviews always make me fidget. The movement knocked off a shoe and it landed near Norman’s foot with a rude clomp. I’d borrowed some too-big red wedges from my flat-mate, Fern. I fumbled it back on.

‘We started two months after the flood,’ he explained. ‘We were six volunteers, now we’re thirty-odd. Not many compared with the big places, but we put the time in. Other helplines were swamped after the rain, so something devoted entirely to flood victims was urgently needed.’

I nodded at Norman several times and wondered if the walls were painted school-PE-shorts-blue to create calm. The shade was at odds with the paisley sofa, velvet chairs and orange cushions. Norman’s voice droned on, as irritating as a wasp in a bedroom.

‘The rain caused all sorts of problems.’ He slurped his coffee. ‘People clearing out their ruined belongings remembered things long buried: affairs, given-up babies, secret abortions. We hear these stories every day.’

The Flood Crisis sign above the window seemed unnecessary. Someone had agreed with me – they’d made an O into a lake and drawn a headless, drowning stickman. Next to his body they’d written, ‘I’ve eaten my own head.’

‘It’s like the water stripped the victims of their inhibitions,’ Norman went on. ‘The floodgates have opened and everything is being washed out.’

‘Like my drawer,’ I said.

‘Your drawer?’

‘There are two drawers in my kitchen,’ I explained, moving my hand as though opening one. ‘They meet at a corner. When one is open, I can’t open the other. They can never both be open. No, wait, that’s the 7opposite of the flood bringing old hurts to the surface. Sorry. It was a stupid metaphor.’

Norman stared at me until I looked down at the black skirt I’d thought suitable for a crisis-line interview and the streaky fake tan I’d hastily applied because my only tights were laddered.

‘We’re here to do the clean-up,’ said Norman.

A steam trains calendar hung above his desk. November belonged to a burgundy one with gold lettering. It would be Jane’s birthday in two weeks, the day after mine. Then Ed would celebrate forty, but, judging by the sad face drawn there, he wasn’t excited about it.

Dates stay in my head, stuck like superglued post-it notes. I’ve a curious knack for remembering birthdays. Friends tell me theirs just once and I remember long after they’ve departed my life. I wake in a morning and look at the date and think of Barry or Anna or Rebecca.

‘How did you feel when your home was destroyed?’ Norman asked.

I returned my attention to him. ‘Pissed off,’ I said. ‘I’d just had Marilyn Monroe’s face painted on my living-room wall. Looks like Billy Idol now.’

Norman ran his skinny fingers through his hair. ‘You really think this is the place for you?’

‘I used to love volunteering.’

‘You did?’

I knew I didn’t appear the best applicant for a role that involved compassion. My mother regularly begged me to stop scowling, especially since I was nearly thirty-one and time was apparently no longer on my side. ‘Wrinkles love frowners,’ she often said, ‘but men don’t.’

‘Yes,’ I offered, more gently. ‘I loved Crisis Care more than anything I’ve ever done. I was there five months.’ I picked at the eczema between my fingers. ‘I never missed a shift, never arrived late. I covered for other people, turned up when I was ill.’

Norman opened my folder. ‘Can I ask why you left?’

He could ask, but I wasn’t sure of the answer. It was easier asking questions. It occurred to me that that might be the attraction. Why 8I was here again, hoping to answer the phones. Perhaps listening to others struggling with their issues meant I could ignore my own.

Norman’s phone flashed, saving me. ‘I’ll let the machine get it,’ he said. ‘We’re not open for twenty minutes. But Jane and Christopher will be here soon so we’d best crack on. Where was I?’

‘Telling me about Flood Crisis,’ I said.

He drained his coffee. ‘We need people who’ve already worked on a crisis line. We don’t have the funding for weeks of training and we don’t know how long we’ll be here.’

‘And what do you offer callers?’ I asked.

‘Some of them call to talk about the rain. Others tell us things they’d never dream of sharing with Crisis Care; I think they find it easier because we’re not officially a depression helpline.’

I glanced at the corner where two glass and plywood booths with pink inner walls looked like wombs; placenta wires snaked along the desks to black telephones that waited for life. I’d answered such phones before. I’d filled notepads with doodles and exclamation marks and words I’d never say to anyone else.

‘Which days can you do?’

‘Monday and Wednesday,’ I said.

‘We’re open five days. Sex Addicts R Us use the place on Monday, and there are two Slim & Trim sessions on Friday. Would you be interested?’

‘No thanks,’ I said. ‘Throwing up is easier.’

Norman scribbled something in my folder.

‘I was joking,’ I said.

‘So you can do Wednesday?’ he asked without looking up.

‘Maybe an occasional Sunday.’ I almost added ‘unless I get any better offers’ but played with the frayed stitching on my bag instead. The silver nail polish Fern had applied three days ago was chipped.

‘There’s no training?’ I asked.

‘We brush up on skills and active listening. Why do you do it?’

I wondered for a moment if Norman was referring to my picking at the seam on the bag.

9‘Why helplines?’ He stopped writing. ‘There are easier ways to help others. Standing behind the counter in a charity shop or filling an envelope with your loose change. Handing out leaflets dressed up as a teddy bear…’

‘Teddy bear suits make me itch,’ I said.

Norman studied me. His eyes were grey, like ash.

I searched for answers. ‘These are real people. It’s not like watching a TV show. The callers’ troubles make mine less, somehow.’

‘And how do you handle yours?’ Norman put his pen into a red cup with a host of others and swivelled the chair to face me, his knee only inches from mine.

‘I don’t have any,’ I said.

A bit of rubbish blew against the windowpane and stuck there for a moment. Someone’s letter. Only the words ‘FINAL CHANCE’ were visible; then it blew away.

‘We all have problems,’ said Norman softly. ‘They must have asked you about them in your Crisis Care interview – I needed a stiff drink after mine, I can tell you. We all cope in some way.’

‘I have sex with strangers,’ I said, immediately regretting it.

‘You make jokes,’ said Norman. ‘It’s a common coping mechanism.’

An ambulance wailed in the distance. Like an echo. Then the doorbell chimed.

‘That’ll be the next shift.’ Norman stretched. ‘Christopher and Jane are here until ten.’ He pressed a buzzer and on the TV monitor above the door I saw a tall man push a bike into the hallway. ‘We buzz each other in if we’re here. Otherwise there’s a door code, so remind me in case I let you go without it.”

On the black-and-white screen, I watched the tall man shove his bike into a gap between the stairs and the wall, remove a rucksack from the basket, hang his jacket up and head for our door. He looked just as two-coloured when he walked into the full-colour reality of the room, his black hair cut short at the sides, but with a longer, floppy fringe, grey T-shirt and dark jeans.

‘Hi Christopher,’ said Norman. ‘Must’ve been bloody cold on your bike.’

10‘Never noticed,’ he said. ‘Music.’ A wire and earpiece still dangled around his neck like a miniature noose.

‘This is Katrina. She’ll be starting soon.’

For a second I wondered whom he was referring to. And then I remembered my new name; Katrina. I smiled. Wanted to whisper it aloud, test it.

‘Hey Katrina.’ Christopher plonked the rucksack by Norman’s desk and untangled his wire.

‘You’re the Christopher Chris then,’ I said.

He smiled and his face changed, like he’d taken Prozac and it had just kicked in. No longer black and white, his blue eyes crinkled with the laugh. ‘Only my mum calls me Christopher; actually she calls everyone Christopher.’

I wondered if he had a middle name that no one called him.

‘Katrina,’ he said. ‘Like the hurricane.’

The buzzer sounded again and a dainty woman came in, perhaps late thirties, with two carrier bags, a box of biscuits and a packet of crisps. Her hair had been cut into a sharp red bob that clashed with her green eye shadow; her hands were like porcelain. I eyed them with envy.

‘You staying for the week?’ Christopher asked her.

She hung her tasselled jacket on a chair. ‘Another bus route cancelled. Travellers should be informed before they leave home, via that Twitter thing or text. This is the modern age after all.’

‘This is Jane.’ Christopher rolled up his headphone wire.

‘You must be Jane who’s really Jane,’ I said.

She didn’t look at me; she loaded the food onto the coffee table shelf, her many bracelets jangling like coins. I would call her Jangly Jane. Not to her face. Jangly Jane – to help me remember her name.

‘We’ll get out of your way.’ Norman pushed his chair under the desk. ‘It was a busy night shift – it’s all in the logbook. The sleet unnerved people; they were worried it’d melt and cause floods again.’ Norman picked up a case and locked a drawer. ‘Shall I turn the phones on?’

‘Go for it,’ said Christopher.

11They began ringing immediately, out of sync, urgent. It seemed like only yesterday that I’d heard the sound. Christopher and Jangly Jane went straight into the cubicles. Jane hunched over the desk and spoke softly. Christopher said, ‘Hello, Flood Crisis, can I help?’ and stretched until almost reclined.

I followed Norman into the hallway and got my coat and scarf. I’d been too nervous earlier to notice more than the stench of damp clothes and old paper. Now I saw a mustard-tiled kitchen, the fire exit and an open toilet door. All crisis places were the same; their cheerless walls oozed depression and addiction.

Norman fiddled with the main door’s latch. ‘I’ll call you about our brushing-up-on-skills day. Warn whomever you live with that I’ll call you Katrina. You can imagine the chaos it causes when we ring with a new name!’ He threw his emaciated hands in the air again.

I fastened my coat. ‘So that’s it – I’m Katrina now?’

‘Whenever you’re here.’

He opened the door and the outside light blinded me. The temperature had plummeted since I’d entered the building an hour before. Having been cocooned in its airless confines I now shivered. Everything was white, like sleep. I took my time going down the steps; my borrowed shoes were as hazardous as the ice.

‘You’re Catherine again now,’ Norman called after me. ‘But only until you come back.’

The words ‘Catherine’ and ‘come back’ followed me down the path, along the street and onto the bus. They haunted me until I slept that night, after tossing and turning for five hours.

3

Everything can be replaced

Teatime traffic meant a long bus ride home. Though long past now, the floods continued their disruption; a circus of caravans and makeshift canopies lined the streets and slowed commuters, driveways packed with cement bags and industrial machines the sideshows. Snow fell on it all like glitter dust on a final act. In front of me a girl breathed on the glass and drew a clown in her mist.

‘Can’t believe they’ve changed the route again,’ said the woman beside me, jabbing her finger at the window. ‘That skip could be moved into a garden. Blocking a main bus route like that – should be ashamed.’

I guessed she hadn’t been flooded; one of the lucky few.

‘I need my kitchen doing,’ she continued, to a bald man across the aisle, ‘and I can’t get a bloody builder for love or money. They’re all doing flood houses, so I’ll be stuck with shit worktops till next year.’

The man shoved his newspaper under her nose and said, ‘They’ve landed on their feet and all they do is complain.’ He pointed out an article squashed between Fern Fielding’s ‘Wholly Matrimony’ column and a picture of John Prescott with a super-sized marrow. ‘Chap here got fifty grand from his insurance company. He’ll be in Majorca by next Tuesday, mark my words.’

A conversation about a woman who’d claimed for a conservatory she never had, using pictures of the neighbour’s lean-to, drifted my way. When the bus stopped and they all got off by the cemetery I was glad.

The little girl in front wiped her clown off the glass and stuck her tongue out at me.

13‘Don’t be rude,’ hissed her mother.

I got off by the street where I’d lived until the rain came; near the house I’d seen ruined that long, wet day. I wanted to walk away, to return when it was rebuilt, when there were walls again, new carpets, doors that weren’t black with mould and a toilet that wasn’t blocked.

But my feet always made the decision and led me there.

Number two was empty; they’d gone to live by the coast. Number four was staying with relatives. A caravan sat on number six’s drive, anchored by piles of bricks. Number eight was mine.

I closed my eyes. Remembered. Snow landed on my cheeks now as rain had that day. That Day. We all called it ‘That Day’. That Day I’d opened the gate, causing a small wave. That Day I’d paused when brown, thigh-high water wet my underwear. That Day waves had lapped at the windowsill, splashed tears against glass. It spilled into airbricks, entered through every hole and crack, uninvited, intrusive. It ruined all that I’d built, all that I had.

That Day.

Now I unlocked the door, forced it open with my foot and stepped inside. No matter how I tried to prepare, the rotten smell always made me nauseous. Wires poked out between the ripped-up floorboards like weeds.

At least the great, alien-like dryers had gone now they’d done their job; my official certificate had come from the drying company a week ago. Dry certificates were the must-have item, like a new games console on Christmas Day. Neighbours called from one caravan to another when they got one. It meant the rebuild could begin. The flood had not won.

Letters fell from the flap when I closed the door: what I’d come for. Still, I couldn’t leave without looking the place over. In the kitchen and living room the lower walls were stripped to brick. The garden beyond the patio doors was overgrown with damp rubbish. Birds pecked for discarded scraps.

I hated to look at the Marilyn Monroe wall, her face dissolved, chin and hair faded. Soon she’d be ripped out and replaced too.

14Upstairs, the furniture I’d managed to save was stacked like boxed cadavers awaiting inspection. Sally-next-door had helped me carry stuff up and I’d done the same for her. We’d removed our shoes and walked barefoot through the water. Dog shit and leaves had swirled into our hallways. Those ruined shoes still hung in the cupboard under the stairs, streaked with salt stains. My mother had said I should claim for them. They were from Clarks and cost fifty quid, she’d said. Fifty quid is fifty quid, she said. Everything can be replaced, she said.

Time to leave.

On my way to the flat I bought a supermarket meal for one, a bottle of half-price wine and the local paper. By the time I climbed the rusting metal stairs at the back of the Happy House takeaway my gloveless fingers were blue.

A mostly naked Fern greeted me. ‘Can’t decide what to wear.’ She took a bottle of vodka out of the freezer.

‘I wish you would.’ I plonked my bag on the tiny granite surface that our landlord, and the Happy House owner, Victor, called a kitchen worktop. The only other storage was a noisy fridge covered in rusting magnets, a double cupboard with no handles and the two drawers that couldn’t be opened at the same time.

‘I’m meeting Greg,’ said Fern.

‘Like that?’

‘He’s taking me to that new Thai place on Chants Ave.’

I put my wine in the fridge.

She poured vodka into a tumbler and added ice. ‘He looks a bit like Princess Diana, but what the hell. Why’d you buy those crappy microwave meals when Victor will give you chicken madras for a quid?’ She poked my frozen meal with a carefully painted red nail.

‘Victor gives you cheap food because you flirt with him,’ I said. ‘For God’s sake put some clothes on, woman, I want to eat.’

‘You got a newspaper?’ Fern headed to the bedroom.

‘What’s it about this week?’ I called.

‘DIY,’ she said, and slammed the door.

Fern had written the ‘Wholly Matrimony’ column for our local 15paper for two years. She hadn’t got around to telling her editor she was no longer actually married. Now separated from Sean for four months, she put as much effort into single life as she did her chatty marital column. Sean often threatened to tell her editor it was a sham. I’d suggested she offer them a singleton column, but apparently Mick Mars wrote one on a Thursday.

I found Fern on page ten. A grainy picture painted her as wifely: hair smooth, a shy smile and an egg whisk in hand; ‘Wholly Matrimony – Dilemmas and Delights of Modern Marriage, with Fern Fielding’.

I put my curry in the microwave and read a few lines:

‘After a calamitous weekend of lawnmower shopping, cake making and DIY, Sean and I found ourselves needing a frothy bubble bath and champagne on Sunday evening. He always sits near the taps, tells me I look lovely in candlelight and massages my thigh with his soapy foot. What more can a woman ask?’

‘How do you think it up?’ I opened the wine and poured a generous amount into a pink plastic cup. ‘Will you still write it when you’re officially divorced?’

Fern opened the bedroom door a crack and said, ‘I’m just deciding between the red take-me-now dress and the silver I-have-class blouse.’

Her separation from Sean had come at a convenient time for me. After the flood, I’d needed refuge, and Fern was looking for somewhere to stay while they sold the house and split the money. Rental property was limited. There weren’t enough places for all those the disaster had left temporarily homeless. Still, most families had turned down our tiny flat overlooking a urine-soaked yard. We’d snapped it up, however; it was close to everywhere, and it was cheap. Fern won the coin toss for the one bedroom, so I slept on the lounge sofa, my clothes stuffed in suitcases under her bed. She might as well have a comfortable bed – I rarely slept for more than five hours a night.

I took my meal to the sofa and turned on the TV. Simon Cowell was telling a man he sounded like a choirboy. While I’d done little to make the place home, Fern had marked her territory with clothes, hair accoutrements and lipstick, spreading all of it over the floor. I hated the 16mess she created. At home my things had been stored in alphabetical order: books, DVDs, even food. I moved Fern’s pyjamas, put my feet on the coffee table and picked at the chicken and rice.

‘This look OK?’

Fern wore a white dress with thin straps. She’d moisturised her shoulders; they shimmered in the soft lamplight.

‘Not the red take-me-now, then?’ I said.

‘No, I’m starving and want to eat first.’

‘You look pretty,’ I said. ‘He’s not coming back here, is he?’

‘You think he’ll want to?’

‘Unfortunately, yes.’ I washed down the tasteless curry with wine. ‘I don’t need to hear what you get up to.’

‘You’ve listened to worse stuff on those crisis lines.’

‘I could hang up when they did that.’

‘Why are you doing it again?’ Fern looked into the broken mirror above the oven, fluffing her hair and blending her lipstick. She stopped, a finger still on her lip like a cheap glamour model, and looked at me. ‘You left last time. The calls made you depressed for days.’

‘Someone has to do it,’ I said.

‘Doesn’t have to be you.’

‘I want to.’ No longer hungry, I dumped the half-empty carton of food on the coffee table. On TV, a man in purple leggings sang Celine Dion.

‘Did the interview go OK?’ Fern asked.

I wasn’t sure. ‘If they ring they’ll ask for Katrina,’ I said in reply. ‘I had to change my name. There’s already a Cathryn but without an i – or a personality by the sound of it.’

‘Nearly forgot. Billy … sorry, Will rang.’

The radiator clunked noisily into action. Fern rambled on about me listening to people whining about the flood, how I’d get sick of it and leave. Water chugged into the radiator pipes. How I hated the sound of it now. I turned to ask what Will had wanted but Fern was already gone, bills and receipts flying from the kitchen worktop in her wake.

17I put them in the drawer that only opened when the other was shut. Outside a gang of kids ate takeaway food near the phone box and mocked an old woman who’d dropped her bags. On TV, the audience cheered a guy who looked like Rod Stewart. The phone rang.

‘It’s me,’ said Will.

I knew the Manchester accent. I remembered the gentle tone he’d used with me when I hadn’t irritated him. But, right now, I couldn’t think of a thing to say. I could only think of the things we had said. The words we’d shared when we were Crisis Care volunteers together. The words we’d listened to on the phones and made into our foreplay.

‘I saw Fern,’ he said after a pause. ‘She gave me this number. Said you’re volunteering again, you had an interview. I was concerned.’

‘Don’t be,’ I said.

‘Why are you being like this?’

I emptied the rest of the wine into my glass. I was sorry for being abrupt but I didn’t say it.

‘I’m just surprised,’ he went on.

‘It’s a flood-crisis line. I was flooded. It makes sense.’

‘I know,’ he said softly. ‘I remember.’

He’d offered me his place when mine went under. I could have moved into his spacious, city-centre apartment rent free, for as long as I needed it; forever he’d said. But since I’d left Crisis Care, a few months before the flood, I had been working up the courage to leave Will, too. We broke up shortly after I rejected his offer of sanctuary.

‘Haven’t seen you in ages,’ he said. ‘How are you?’

‘Great. We love it here.’ I didn’t tell him I was restless, my eczema had flared up again, and I often had insomnia. ‘Why are you ringing?’

‘I didn’t want you to hear from anyone else…’

‘Hear what?’

Two women in gold cat suits sang the theme song to Beauty and the Beast. Simon Cowell put his head in his hands.

‘I’m getting married,’ said Will.

Everything can be replaced, my mother had said of shoes.

‘Congratulations.’ I swigged my wine. ‘Is she pregnant?’

18‘No. We’ve been together three months, and it’s good. She’s a great girl: reliable, kind. She doesn’t mess me around.’

‘So does she have a name?’

‘Miranda,’ he said.

Everything could be replaced, I thought again. ‘I’m happy for you,’ I said, and I was. I just wasn’t sure why I needed to know about it, though. ‘I bet your mum’s glad. She never liked me, which is understandable – if I had a son I wouldn’t want him dating me.’

Will laughed. ‘Remember the time she took us to that place in Cottingham and the waiter heard you saying he looked like a rent boy and you were embarrassed and my mother wanted to know what you’d said and the waiter told her?’ I could tell he was smiling. ‘You always made me laugh, Catherine.’

I watched a guy in an advert hold up a wipe with all the dirt he’d cleaned out of his pores.

‘Do you remember that caller at Crisis Care?’ he asked. ‘That guy who cut bits out of himself with a razor. Frank. Had a lisp. Said that by removing those chunks he could disappear. That when he was invisible he might have the power to confront his mother. She’d locked him under the stairs, tied him up, burnt him and bit him.’

‘I remember.’ I pressed my glass to my cheek.

‘He still calls,’ said Will. ‘He took his mother to Home Farm and told her while she ate a prawn cocktail starter that she’d hurt him. He doesn’t cut anymore.’

‘That’s good,’ I whispered.

‘Why did you leave?’

‘I couldn’t do anything for those people,’ I said.

‘I meant why did you leave me?’

I shifted the receiver from one ear to the other. It was a habit formed in my days at Crisis Care. It sometimes helped at two in the morning when I’d been on the phone for hours and my ear throbbed and my neck ached and my heart hurt.

‘I know why you left Crisis Care,’ said Will. ‘But why did you leave me? Didn’t I put up with more than anyone normal would?’

19‘Will…’ I said, gently.

‘You’re still calling me that?’ He paused and I thought he’d hung up. ‘No one calls me Will.’

‘It’s just a name,’ I said.

‘Bullshit. All that crap about you calling me Will to make me feel special. It’s to make you feel special.’

A car alarm shrieked outside; I jumped and knocked the wine glass over. ‘Dammit.’ I tried to catch the liquid as it dripped from the coffee table.

‘What do you mean dammit? It’s true.’

‘Not you,’ I said. ‘I spilt my wine.’

‘Enjoy it, Catherine,’ he said.

‘Enjoy your girlfriend.’ I slammed the phone down.

Oh, the times I’d wanted to do that at Crisis Care. The times I’d listened to a teenage girl crying because she was on a bridge, staring at the water and thinking of jumping. The times I’d wondered why my face was wet when a middle-aged guy confessed to fantasising about his fourteen-year-old nephew. The times I could have walked out. And yet I’d lasted.

Until the nightmares began.