7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

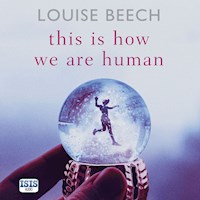

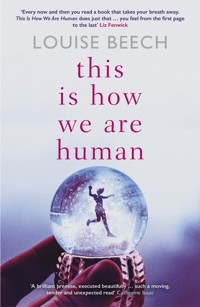

When the mother of an autistic young man hires a call girl to make him happy, three lives collide in unexpected and moving ways … changing everything. A devastatingly beautiful, rich and thought-provoking novel that will warm and break your heart… 'One of the best writers of her generation' John Marrs, author of The One 'A brilliant premise, executed beautifully … such a moving, tender and unexpected read' Catherine Isaac, author of Messy, Wonderful Us 'I guarantee you will not read anything like it this year … you will fall in love with this book' Miranda Dickinson, author of Our Story 'Incredibly moving, gripping, and full of heart … The novel everyone will be talking about this year' Gill Paul, author of The Secret Wife _______________ Sebastian James Murphy is twenty years, six months and two days old. He loves swimming, fried eggs and Billy Ocean. Sebastian is autistic. And lonely. Veronica wants her son Sebastian to be happy … she wants the world to accept him for who he is. She is also thinking about paying a professional to give him what he desperately wants. Violetta is a high-class escort, who steps out into the night thinking only of money. Of her nursing degree. Paying for her dad's care. Getting through the dark. When these three lives collide – intertwine in unexpected ways – everything changes. For everyone. A topical and moving drama about a mother's love for her son, about getting it wrong when we think we know what's best, about the lengths we go to care for family … to survive … This Is How We Are Human is a searching, rich and thought-provoking novel with an emotional core that will warm and break your heart. _______________ 'Every now and then you read a book that takes your breath away. This is How We Are Human does just that … you feel from the first page to the last' Liz Fenwick, author of The River Between Us 'A writer of beautiful sentences, and they are in abundance. This sensitive subject is treated with the utmost care' Nydia Hetherington, author of A Girl Made of Air 'Such a complex and emotive book' Claire King, author of The Night Rainbow 'It had me gripped from the start and changed the way I see the world. Beautiful, bold and compelling – another fearless story from Beech' Katie Marsh, author of Unbreak Your Heart 'A searching, rich and thought-provoking novel with an emotional core' LoveReading 'This book is just what the world needs right now' Fiona Mills, BBC 'Oh, Sebastian, I'll never forget him. Heart is always at the core of Louise's books and this one is no exception' Madeleine Black, author of Unbroken 'What a brave and prejudice busting story this is … brava' S. E. Lynes, author of Can You See Her 'A convincing, bittersweet tale of misplaced kindness, a myriad types of vulnerability, and unexpected consequences … All the stars and more' Carol Lovekin, author of Wild Spinning Girls 'A tender, insightful read' Michael J. Malone, author of A Song of Isolation 'An exceptional book that will make you laugh, cry and feel better for having read it' Audrey Davis, author of Lost in Translation 'The most exquisite and moving story I have read in a very long time' Book Review Café 'I don't know of another writer who portrays characters so true, flaws and all … mesmerising, the characters are beautiful but, more importantly, they're REAL' J. M. Hewitt, author of The Quiet Girls For fans of Maggie O'Farrell, David Nicholls, Ali Smith and JoJo Moyes.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 438

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Sebastian James Murphy is twenty years, six months and two days old. He loves swimming, fried eggs and Billy Ocean. Sebastian is autistic. And lonely. Veronica wants her son Sebastian to be happy … she wants the world to accept him for who he is. She is also thinking about paying a professional to give him what he desperately wants.

Violetta is a high-class escort, who steps out into the night thinking only of money. Of her nursing degree. Paying for her dad’s care. Getting through the dark.

When these three lives collide – intertwine in unexpected ways – everything changes. For everyone.

A topical and moving drama about a mother’s love for her son, about getting it wrong when we think we know what’s best, about the lengths we go to care for family … to survive … This Is How We Are Human is a searching, rich and thought-provoking novel with an emotional core that will warm and break your heart.

This Is How We Are Human

Louise Beech

This book is dedicated to the Mills family, and to Joanne Robertson’s little Sebastian.

‘The need to be together, against all the odds, to stand side by side – whatever the grindstones of life permit – and to feel that the very stars dance in each other’s eyes transcends all; love is solemn simplicity; and is inevitable’

Wolfy O’Hare

CONTENTS

1

SEBASTIAN GETS READY TO SINK

I love it here. I love this river. It’s freezing this morning though. It’s seven-fifteen. Not the right time yet. The water looks colder than I am. It’s bouncy and brown and moody. The sky is too. Clouds rush away from it. Even with my red coat and my leather gloves and my Hull City hat and my Puma trainers on, I shiver. I’m glad I’m not taking them off. Normally I take all my clothes off and just wear trunks and goggles when I swim. Really, it’s like how you get ready to have sex. I’m going to miss sex. And swimming. But I don’t want to swim here.

This morning I have come to sink.

There are two benches here. The left one was my dad’s. We ate sandwiches here like this was our living room with a river going through it. We always took our shoes off too, no matter how cold it was. But today I need them on to help me sink.

It’s seven-twenty now.

Not time yet.

I open my notepad at the How To Sink list. Number one is The Bigger The Water The Easier It Is To Sink. You are less likely to float if the volume of water is greater than the volume of you. Number two is Wear Very Heavy Things. I stand. It’s seven-twenty-five.

Almost time.

I climb over the rocks to get to the water. There are gaps that try and trap me. It’s a good job I must keep my shoes on. I’m out of puff when I reach the small beach. The waves lap at my Puma trainers while I catch my breath. They’re ruined, which is a shame because they cost fifteen pounds fifty.

I read the rest of my How To Sink note. Number three is Take A2Vertical Position In The Water With Your Feet Pointing Down. I’ll do that when I get to the middle. Number four is Get Into A Tucked Position. This is because objects sink in water if they take up less space. I know the rest. Just do the opposite of everything I normally do to try and float.

It’s seven-thirty now. It’s the right time.

It used to be my favourite time when I was with HoneyBee. Now it’s my last time. So here I go.

To sink.

2

VERONICA GOES TO THE SEXUAL HEALTH CLINIC

Veronica is monstrously overdressed.

The pink silk scarf and delicate diamond drop earrings that she chose carefully this morning now only accentuate how different she is to the other women in the Rowan House waiting room. Most of them are less than half her age and look as though they’re attending a gym or social club. A fug of cigarette smoke and celebrity perfume emanates from their young pores. Veronica muses that Sebastian, who’s making himself comfortable in the corner by some books, looks far more suited to the place in his baggy grey joggers, Superman hoodie, and brand-new Puma trainers that he only wears on special days.

Perhaps it’s a good sign; perhaps he is in the right place; perhaps they are in the right place. Perhaps someone here can help her.

Abandoning a pamphlet about sexually transmitted diseases, Sebastian returns to Veronica.

‘Mum,’ he says. ‘That woman with big, zazzy hair looked at me like she might want to have sex with me.’ His swimming goggles are wrapped around his wrist, and he still has a trace of egg yolk on his softly stubbled chin. Veronica wipes at it with the edge of her lace sleeve.

‘Fucking pervert,’ says the woman in question under her breath.

‘Really,’ sighs Veronica. ‘There’s no need for that. He’s jus—’

‘He just needs telling,’ she says, her purple-mascaraed eyes glaring.

Veronica stands and strides purposefully to where the woman sits, grateful now of her armour, of her dusky Valentino coat, of her favourite scarf. Fear lights the woman’s eyes, just a flicker, then it’s gone. Then she scowls. 4

‘Sebastian is autistic,’ Veronica says in a low voice. ‘Only stupid sees stupid. Only pervert sees pervert. I’ll thank you to mind your language.’

‘Me mind my language? He’s the one who fu—’

‘Cheryl Cooper,’ calls the receptionist. ‘Room three please.’

The zazzy-haired woman stands, squares up to Veronica for a second, and then tuts and heads down the corridor. Veronica returns to her son. Sebastian is flicking through Sex Health magazine now, his wild, wavy hair lifting at the turn of each page. How beautiful he is to her; perfect. She can behold him for hours. That’s the best word to describe it – behold. Curled lashes that would make a model jealous, eyes the colour of ripe acorns, chubby lips perfect for kissing, cheeks she can never resist pinching.

‘I thought it would be more like Love Island, Mum,’ he says.

‘It’s a clinic, darling. We talked about it last night.’

‘You said it was a sex house.’

‘No, a clinic, where people talk about sexual issues.’

‘But I don’t want to talk about sex. I want to have it.’

‘I know that, bu—’

‘Can we go to KFC after this?’

‘We’ll see.’

‘Veronica Murphy,’ calls the receptionist. ‘Room four please.’

‘Can I take this?’ asks Sebastian, holding up the magazine. ‘There’s a picture of a tiger on a woman’s bottom on page thirty-four.’

‘What?’ Veronica flicks to the page. The image is of a roaring tiger tattoo on a semi-clad woman’s left buttock. ‘No, I think we’ll leave this here, darling.’

They head along the corridor, past rooms one, two and three. Veronica knocks softly on door four and a sharp voice calls, ‘Come in!’

Sebastian pushes in first, keen as always to investigate the room, to see where the books are, if there are any fish, and to pick the best seat. In the main chair at the desk sits a woman who looks like she hasn’t eaten meat for a good few years. A green polo neck is one 5size too big and sags at her pale neck; wooden beads scream I love all things natural and I’ll judge your plastic shoes.

‘Please, take a seat.’ She gestures to the chairs by the window. ‘I’m Mel.’

Sebastian sits on the chair next to Mel’s and says, ‘I’m Sebastian James Murphy and I’m twenty years and six months and two days old.’

‘Oh. Hello.’ Mel seems uncomfortable having him sit so close that their knees touch. Veronica sees in her eyes the things she has seen in so many eyes over the years. Flashes of discomfort, sparks of mild repulsion, flickers of why does he have to bother me?

‘Sebastian, remember about boundaries.’ Veronica pats a seat next to her, by the window. ‘Maybe you should sit with me.’

Joining his mum, he says, ‘She doesn’t have any fish.’

‘Not everyone does.’

‘Mine are called Flip and Scorpion. They’re bright gold.’

Mel opens her mouth to speak but is interrupted by a soft tapping on the door. She responds in the same sharp tone she used earlier. A girl bursts into the room, out of breath, damp hair the colour of spring daffodils stuck to her forehead. Girl is the word that comes to Veronica, though she is perhaps almost thirty. The gust of air sends papers tumbling from the desk; she picks them up, apologising profusely, her white uniform with blue lapels gaping as she bends, revealing a hot-pink bra. The sexiness of the garment contrasts with the girl’s youthful appearance so sharply that Veronica exhales – and realises she is staring.

‘This is Isabelle,’ says Mel.

‘So sorry, my car was be—’

‘Isabelle is a student nurse in her final year, and if you don’t object, she’ll be sitting in today.’ Mel doesn’t look at the girl, but her narrowed eyes make clear how unimpressed she is by her lack of punctuality.

‘I am happy she is here,’ says Sebastian.

‘It’s fine by me,’ agrees Veronica.

Gratitude colours Isabelle’s eyes. She sits next to Mel, moving 6 the chair away slightly as she does. Veronica stifles a smile at this subtle assertion of autonomy. Isabelle crosses her legs and pulls down her skirt. Sebastian has not taken his eyes off her; she smiles at him with the warmth of a late summer evening.

‘What brings you here today, Mrs Murphy?’ asks Mel, all business.

‘I’m here about my son.’

‘That’s me,’ says Sebastian.

‘And what seems to be the trouble?’

Veronica composes herself, makes sure her scarf is perfectly smooth. She has been here before. Been to see doctors and social workers. Been to various autism support groups. She has told her tale many times in the past few months and had it fall on unsympathetic, unhelpful, unsure, and unable-to-do-anything ears. This time, no decorating it with gentle words or holding back. She has worn her softest colours, her most elegant earrings, but she will talk hard.

‘Sebastian thinks about sex all the time,’ she says.

‘Stop talking about me,’ he interrupts. ‘Why are you talking about me? I’m right here.’

‘I know, darling. But this is something I have to say here, OK? If I say anything that isn’t true you can tell me, can’t you? Remember, I said this morning that I would be talking about you, but you’d be here, and you can comment anytime?’

‘I’m just going to look at Isabelle.’

She smiles.

Veronica returns her attention to Mel. ‘You see, Sebastian’s sex drive is on fire. He’s obsessed with it. And that would be fine if he were able to just go out and meet someone like other young men his age and, you know’ – Veronica coughs, embarrassed – ‘do the sowing the wild oats thing that they do, but he can’t, can he? He’s autistic, as I imagine you’ve realised, so this limits his ability to mix with and meet girls.’

‘I see. Well, these urges are very natural in a man of twenty, no matter what special needs he has.’

‘Twenty years and six months and two days,’ corrects Sebastian. 7

‘Yes, they are,’ says Veronica. ‘But he’s a young man who has no means of … well, of satisfying his needs. You understand that? His needs are just a joke to most.’

‘Not to me.’ Mel is a picture of professionalism.

‘Maybe. But to most people he’s the stuff of The Undateables.’

‘Not here,’ insists Mel.

Veronica looks Mel firmly in the eye. ‘I saw how you responded when Sebastian sat so close to you earlier.’

Flustered, Mel insists she would have been the same if anyone had insisted on sitting so close, so suddenly.

Veronica catches Isabelle’s eye. She gets it, thinks Veronica. She didn’t see Mel recoil from Sebastian, but she believes me.

‘This room would be better with fish,’ says Sebastian, unwrapping his goggles from around his wrist and putting them on his forehead, flattening his wild curls and making it look like he has four eyes.

‘He can’t meet people easily the way any of us can,’ Veronica says to Mel.

‘I can, they’re just not able to see me properly.’

Veronica nods. ‘Sometimes it’s hard for you to understand what young women’s facial gestures mean, isn’t it, darling?’ To Mel, she says, ‘Everyone thinks autistic people can’t read faces, but there’s no proof. Sebastian is an individual. Autism isn’t one size fits all. He generally knows my expressions. But young girls? That’s tricky.’

‘Have you tried talking about it with him?’

‘Of course I have. We talk about everything, don’t we, darling?’

Sebastian shrugs.

‘Sex is everywhere. In music videos and soap operas. He loves watching Love Island, and of course on there they swap beds in a matter of days. So he probably thinks it’s something you can have, whenever and wherever and with whomever you want.’

‘Which of course you can’t,’ says Mel, her tone even.

‘I know that! For God’s sake, he’s not a pervert.’

‘What’s a pervert?’ asks Sebastian. ‘The zazzy-haired woman said I was one.’ 8

‘Which zazzy-haired wo—’ starts Mel.

‘Look,’ snaps Veronica, ‘I just need someone to talk with him. Guide him. I can’t find the right help. He’s not a pervert; he’s my only child. His father died when he was seven and it’s been just us ever since. I don’t know what to do. I’m exhausted. He doesn’t have any close friends his own age, you know, to maybe talk to. There’s just … me.’

Sebastian grabs a leaflet on Sexual Health, Asylum Seekers and Refugees, pulls his goggles over his eyes, and flicks through it without pausing to read a line. He then hands it wordlessly to Isabelle, who smiles, dons some tortoiseshell glasses she finds on Mel’s desk, and does exactly the same. When she is done, she shrugs. He shrugs back.

‘Does Sebastian have a support worker?’ asks Mel.

‘No, I never felt I needed anyone … until now. I’ve been to see various people about this. My doctor told me to come to a clinic like this, since you specialise in sexual matters.’

‘Look, before we go on, let me ask a few questions about Sebastian so I can ascertain exactly what help we might be able to give.’

‘I like eggs,’ he says. ‘I like swimming. I like tigers. I like Billy Ocean. And I know I would like sex if I could get it. Have you had sex, Isabelle?’

‘Yes,’ she says.

‘Is it good?’

‘It’s best with someone you love.’

‘OK,’ says Veronica to Mel. ‘Ask whatever you need to.’

‘How old was Sebastian when he was diagnosed, and what led to it?’

‘I suppose I always knew. A mother just does. Then he went to nursery at three and I noticed his lack of interaction. While the other kids were mixing, Sebastian was running in circles around the room, flapping his arms like a little bird. The nursery nurse suggested I talk to someone. A doctor referred us to the children’s centre, and they assessed him. Said he had Autistic Spectrum Disorder.’ 9

Veronica feels her throat tighten. She will not cry; she will not. Isabelle’s face softens, and she leans a little further forward in her chair. Sebastian has twisted his goggles around to the back of his head so that the elastic cuts through his closed eyes.

‘Sebastian calls it “autism spectrum perception”,’ says Veronica, sadly.

‘Yep,’ he says.

‘Has he ever taken medication?’ asks Mel.

‘No, never. It was offered to us all the time, especially when he didn’t sleep. But I never wanted my boy all drugged up.’

‘Just to help me in how we deal with your current issue … I can see that Sebastian is physically twenty years old, but how old is he emotionally would you say? Mentally?’

‘Mentally, he’s very intelligent. He reads a lot. Has opinions on everything. He’s like a sponge. Emotionally, that’s the tricky one. You can’t give an age to something like that. If I told you he was a sixteen-year-old at times, you’d say he was a child. But he isn’t. He goes to college three days a week and—’

‘An everyday college, not a specialist one?’ asks Mel.

‘An everyday one.’ Veronica resists verbalising her outrage. ‘He’s doing his level two in bricklaying – he passed level one – and he’ll eventually get a level-three diploma. Last month, for example, I was ill one day and couldn’t move. Our housekeeper, Tilly, was away that week. After giving me a stern chat about taking things easy, Sebastian put a wash on and changed the bedding, and went to a local shop with a list and got everything on it.’

‘She still didn’t take it easy,’ says Sebastian.

‘He can physically live an everyday life.

‘Yep.’

‘But he’s vulnerable to … suggestion. He’ll take what you suggest literally. Change scares him. If he got off the college bus at the wrong stop he’d panic because he’s out of his comfort zone. But he would know to ask someone for help.’ Veronica shrugs. ‘You can see how tough this is. A sexually mature body demanding what it needs, belonging to a … well, a vulnerable adult.’ 10

Mel nods. ‘Do you just need me to talk to him, one on one, do you think?’

‘I don’t know,’ says Veronica at the same time as Sebastian says, ‘No, thanks.’

‘OK,’ says Mel. ‘Tell me, on a day-to-day basis, what it’s like with Sebastian. Is his high sex drive the only problem?’

‘Yes,’ says Veronica. ‘No. Look, he doesn’t understand boundaries, not like you and I do. He needs someone to explain consent better than I can. I’ve tried. I showed him that Tea and Consent thing where if you can understand when it is and isn’t OK to serve tea, then you understand consent. It was on social media. I think Thames Valley Police came up with it. But all Sebastian said was “I don’t like tea”.’

‘I don’t,’ he says. ‘It isn’t hot chocolate.’

Veronica kisses his cheek. He wipes it off and smears it on the wall. She still hasn’t been as frank as she needs to be. The words are choking her. The room feels small.

‘He asked me the other night why he is twenty and hasn’t—’ starts Veronica softly.

‘Twenty years and six months and two days old,’ corrects Sebastian.

‘Younger men than him have had lots of experience by now.’ Veronica pauses. ‘I worry that he might…’

‘What?’ asks Mel.

‘Look, he knows that women have to be eighteen. I know it’s sixteen, but I felt telling him eighteen was better.’ Sebastian frowns at her, opens his mouth to speak, but she quickly continues. ‘He can be very … well, forward. He is happy to tell you his thoughts. I worry…’

Veronica glances at Isabelle. She’s wearing the tortoiseshell glasses upside down, mirroring how Sebastian has now positioned his goggles.

‘Do you think he would ever force anyone?’

‘God, no. There isn’t a violent bone in his body.’

‘There are two hundred and six bones in the body,’ says Sebastian. ‘Mine are all good bones.’ 11

‘But he could end up in trouble, yes?’ Mel’s brow furrows with exaggerated concern. ‘If he said the wrong thing to a young girl. Remember, she doesn’t know he has autism. And neither do her parents.’

‘This is why I need help,’ admits Veronica.

‘Did the doctor suggest some sort of medication to supress the sex drive?’

‘Yes, but I already told you, I don’t want him drugged. I don’t want him to think his sexuality is wrong. It isn’t. It’s entirely natural. I want him to know he’s not strange or bad or wrong.’

‘Have you suggested that he try and meet someone similar to him?’ asks Mel.

‘You can ask me, you know,’ says Sebastian. ‘I’m still here. I haven’t disappeared into skinny air.’

‘Do you want to tell them about the university dance then, darling?’ asks Veronica.

‘Nope.’

Veronica turns to Mel. ‘I suggested going to the weekly special-needs dance, and he just said, “Will I get a girlfriend?” I said possibly. And he said, “But I don’t want her to have autism. I want to breed it out of the family.” Those were his exact words. But everyday girls aren’t interested in him. Occasionally I see them looking at him. I know he’s lovely on the eye, and they see that. But the minute they talk to him…’

Mel nods. ‘Look, I can certainly refer him for something one-to-one. Would you want him on his own in a room with anyone?’

‘He won’t understand. I’ll have to be there too.’

‘I honestly don’t know what else we can do then.’

Veronica imagines walking out of this stifling room, away from Mel’s clunky wooden beads and fake-concern nods, away from the young student nurse who is clearly taken with Sebastian enough to give him all her attention, away from her beautiful boy, and not coming back. No. No. How can she want such a thing? The guilt at thinking, even for a second, that she can abandon him strangles her. She undoes her scarf and puts it on her knee. Tries not to sob. 12

‘Isabelle,’ she says, ‘I wonder can you take Sebastian outside for a few minutes? I need to say something in private to Mel.’

‘Are we going to have sex?’ Sebastian asks, eyes shining.

‘No, but I do know where there are some fish,’ says Isabelle, standing.

‘Where?’

‘Come on, I’ll show you.’

As Isabelle is closing the door she gives Veronica a comforting, I’ll take care of him smile.

3

VERONICA SPITS IT OUT

Mel looks expectantly at Veronica. Veronica realises it is time to say it. To spit it out. The thing she thought of the other night – alone, in tears, in her dark kitchen – but fears saying aloud.

‘They hurt him,’ she says first.

‘Who?’ asks Mel.

‘Some kids on the bus. The other week. They weren’t from his college or I’d have had them expelled.’ Veronica closes her eyes and recalls the moment Sebastian walked through the door, jacket ripped and cheek bruised, still singing a Billy Ocean song. She tried to touch his face, tearful, demanding what on earth had happened. Sebastian shrugged and said he was OK. ‘They played a pornographic video on a phone and got him all wound up and then they laughed because he was aroused … and beat him up.’

‘That’s terrible,’ says Mel kindly.

‘He wouldn’t tell me who they were.’

‘They need reprimanding.’

‘It isn’t the only time. Some of the boys on his course, they tease him. They know he hasn’t had sex. I only know because his tutor told me. Sebastian didn’t. But he…’ Veronica’s voice wavers. ‘He denied it when I talked to him. The other night he said that if he doesn’t meet a girl, he might die.’ Veronica has to breathe deeply not to cry.

Now spit it out, she thinks.

‘I’ve been thinking,’ she says, ‘that there is an answer. A way. I could just pack and we go to Amsterdam and I take him to a … well, a professional person. You know – a woman of the night. Someone who can meet his needs.’ 14

‘How old is he again?’

‘Twenty.’

‘No, I mean emotionally.’ Mel fiddles with her beads. ‘You said he’s more like a teenager, so I have to advise that this would be highly inappropriate.’

‘No.’ Veronica controls her voice. ‘He is not a child.’

‘But still, you’re talking about going to Amsterdam and taking a vulnerable adult with special needs for a night in the red-light district?’

‘It wouldn’t be like that,’ snaps Veronica.

‘What would it be like?’

Veronica regrets sharing her idea. Faced with Sebastian’s bruised face, it came to her, a seemingly simple solution. She hasn’t really thought about the how. She hasn’t made actual plans. Now she feels ashamed. ‘I’m only thinking about it.’

‘I don’t think legally that I can advise or recommend something like that.’

‘You don’t understand. I feel helpless. I can’t bear his distress. He hasn’t shown it here, today, but I see it. Every day, asking when will he have sex. Asking why doesn’t anyone like him. Can you imagine how that makes me feel? If I could just … make him happy. I’ve always been able to do that. But this … how can I?’

‘Maybe go back to your doctor – the answer might be medication.’

‘I’m not going back there,’ cries Veronica. ‘Why do I need to calm him down?’

‘Maybe he’s not emotionally ready to be having sex.’

‘How the hell do you know what he’s emotionally ready for? I’m his mother and I know exactly what he’s ready for.’

‘Perhaps if he was emotionally ready, he would have found somebody.’

Veronica is momentarily wordless. She imagines taking hold of Mel’s wooden beads and wrapping them tightly about her throat until she passes out and the patronising look on her face dies.

‘Have you any idea how to deal with human people, never mind 15autistic people?’ she asks softly. ‘Or is everything you know something you’ve read in a book?’

‘I could refer you to somebody,’ says Mel, coolly.

‘Right, I think we’re done here.’

Veronica stands, flicks her scarf back around her neck, and gathers her bag from the floor.

‘I have to tell you,’ says Mel, ‘that if you do take him to a prostitute, then I’m obliged to inform the social-services team. I have to safeguard a vulnerable adult.’

‘Then I’m telling you nothing!’

Veronica strides from the room, head high, and draws on all her strength to close the door quietly. She leans against it, clutching her lapels with trembling hands. Laughter from nearby. Sebastian and Isabelle are at the opposite end of the corridor, by a large tank full of luminous tropical fish. He has the tortoiseshell glasses on upside down and she wears his goggles. He flaps his hands, not in panic, but to mimic a large rainbow fish that swims in circles.

As Veronica approaches them, she hears him say, ‘I’ve got two fish. In their tank, fish can see all of us and hear all of us, but they’re separate.’

‘We have to go now, darling,’ says Veronica, gently.

‘I don’t want to leave, Mum.’ Sebastian shakes his head. ‘I like Isabelle. She likes me. We look at things with the same eyes. Look – we swapped and tried each other’s on.’

‘Isabelle has to work now. You said you wanted to go to KFC.’

‘Yes, yes, KFC.’

Sebastian takes his goggles carefully from Isabelle’s head and puts the glasses on her, then goes back towards the waiting room.

‘I might just be a student,’ says Isabelle, watching him tidy his hair in the reflection of a large-framed poster, ‘and I don’t know what I would say in your difficult circumstances, but I wouldn’t say some of the things Mel did.’

‘Thank you.’ Veronica is moved by this young creature with skin like ivory soap and sad, sad eyes. ‘You’ll make a very special nurse. How long have you got until you graduate?’ 16

‘Six months.’

‘Are you specialising?’

‘My degree is in learning disability.’

‘Wonderful,’ smiles Veronica. ‘Do you know what area you want to go into?’

‘I’m not entirely sure yet. I think I’d like to work with children or young adults.’

‘Will you look for work around here?’

‘I’m not sure yet.’ Isabelle isn’t guarded, rather she seems unable to say the many things that flit across her face.

‘I hope so,’ says Veronica. ‘We could do with more nurses like you.’ Sebastian has disappeared around the corner. ‘Look, I have to go. But thank you. And good luck in your career, wherever you go.’

Veronica heads back to the waiting area, sure she feels Isabelle’s eyes following her. But when she looks back, Isabelle has gone, and the large rainbow fish is still the only one swimming in a circle. Veronica can’t help but wonder if she’s imagined the young nurse, and that if she were to call the clinic tomorrow, they would ask her, ‘Isabelle who? We don’t have anyone called Isabelle here.’

When she finds Sebastian studying a book about the Aztecs, she is back in the world where only they exist.

4

ISABELLE WRITES A NOTE TO THE NIGHT

Dear Night,

I dream of strangling Dr Cassanby to death with his black silk tie. All the time. He makes me choke him with it until he almost passes out sometimes, but I want to do it until he’s dead.

It’s weird – he looks a bit like my dad did ten years ago. He’s not as heavy in the face and stomach, and he’s taller, but the determined way he walks is my dad. And that only makes me hate Cassanby more because it makes me miss my dad. The old one, anyway. The one I don’t have anymore.

He takes me to the Westwood Restaurant for dinner and afterwards he sucks on a cigar, which he only smokes after red wine, he says, then chews some gum. I have to smile through clenched teeth. Then he drives us back to his house (which is beautiful in a way that rarely used homes are) and asks me to unfasten that wretched shiny tie, wrap it around his limp wrists and tug on it until the skin chafes…

Isabelle puts down her pen. She shakes one of her snow globes and sets it down on the desk. While the spiralling storm within settles into calm, she closes her book, marking the page bearing the half-written note with a perfume sniffer stick. She writes her notes to the night because it’s the only way of getting through the dark. They remind her of the letters she wrote to her dad when he used to go away, so it comforts.

Standing, she unclips her buttery hair. She then unfastens her white-and-blue student nurse uniform and stands, letting it fall to the floor with a whisper. It’s time to discard not only her clothes 18and her tidy hairstyle, but her inhibitions, her pride, and her self-respect.

Within the glass dome, the flakes settle on the plastic gold-and-black New York skyline like white ash after a fire. It’s her favourite snow globe. It was the first one her dad bought her. She was eight when he came home from that city with it. She clapped her hands so happily that afterwards he found her one in every city he visited. They line the desk and windowsill and bookshelves. Glancing at them now, at the silent cities, it occurs to Isabelle that right now her dad is also trapped in a bubble.

But no matter how hard she shakes him he never opens his eyes.

Isabelle takes her black stockings from the bed How she hates them. They would be as effective a strangulation device as Cassanby’s tie. Instead, she must roll one up each leg, clip them on to matching suspenders, and go and tend to the doctor for two hours, for which she’ll be paid four hundred pounds in crisp notes – perhaps an extra fifty tip if he climaxes twice – and a box of chocolate liqueurs that she will give to her dad’s main nurse, Jean.

After a long day Isabelle is not in the mood.

Is there any day that would have her in the mood?

No.

But choice has never been an option when it comes to her night work; when it comes to the creature she transforms into as darkness falls. Who on earth would choose to spend hours studying Managing Complexity in Learning Disability during the day and then leave the house at seven o’clock to work all evening? Who would choose to end up so exhausted they fall asleep in lectures and have to work twice as hard to catch up? Who would choose to constantly fear the moment someone at university or in everyday life recognises them as the escort they paid to slap them with a shoe last night?

Isabelle knows something has to give – somewhere, somehow – but being a nurse is her dream, and the escorting is a necessity, because everything is different now.

‘We’re not what we do, we’re what we dream of doing,’ her dad 19told her once. ‘Never give up on your dreams, lass They’re not meant to happen easily. If they were, why would we reach for them? They’d simply drop into our laps.’

Isabelle dreams of finishing university in six months and starting work as a nurse, helping youngsters with special needs. She dreams of the changes she might make to other families. Most of all, she dreams of the day her dad comes back to her.

Sliding a black stocking through her fingers, it’s all she can do to not rip it apart and fall on the bed crying. What would her dad say if he knew this was what she was doing? But there’s no other way to keep him in the place he loves, the place he worked so hard to get, the place he’s now oblivious to. He need never know, Isabelle decides. When he returns to her, she’ll come up with some story to explain how she took care of him; she just can’t think of it now.

Now she must go out into the night.

She must put on her armour; she must paint her mouth fire-engine red and outline her eyes in smoke grey. She must step into her spike heels and spray on Chanel No 5 and go out into the cold January night and tend to Dr Cassanby.

How did it come to this?

5

ISABELLE LOOKS BACK ON HOW IT CAME TO THIS

Isabelle’s dad owns three casinos in the region. He has always worked in the entertainment industry, previously running clubs, managing cabaret acts. Privately, she thought that casinos just cash in on the desperate, but she couldn’t help but love seeing her dad so passionate about what he saw as his other three babies, so she kept her thoughts to herself.

One evening, about seven months ago, Nick – the manager of the biggest casino – came into the kitchen, where Isabelle was studying. He was there to see her dad, who had just this minute left for work, calling from the hallway that he’d see her in the morning. Nick is like an uncle to Isabelle. Many find him intimidating, with his surly attitude, shaved head, and crisp grey suits, but she knows the soft layers beneath.

‘I’m worried about Charles,’ he said.

‘What do you mean?’ Isabelle’s chest felt tight.

Nick started out of the room, shaking his head. ‘Sorry, I shouldn’t ha—’

‘You can’t not tell me now.’ Isabelle stood, spilling coffee across the laptop keyboard. ‘Damn it.’ She grabbed some kitchen roll. ‘Nick, is he OK?’

Nick sighed and returned to the table. ‘I just … He seems extra tired, don’t you think?’

It was true. A normally vibrant man, he hadn’t seemed himself in recent weeks. But she realised that Nick wasn’t being completely honest. ‘That isn’t just it, is it?’ she said.

‘No. It’s…’ Nick shook his head. ‘He’ll never tell you because he wants to protect you.’ 21

‘Nick, I’m twenty-nine not nine. Tell me.’

‘I didn’t know whether to tell you, but, yes, you do deserve to know.’ He paused. ‘Financially … things aren’t going well. Clientele is on the decline.’ He sighed, annoyed. ‘Online gambling has a lot to answer for. It’s so much easier to keep a habit secret on your smartphone than to visit a venue. But Charles insists it’s just a slump. I think we’re in trouble though … But, well, he’s a proud man. He’s always made sure you’re OK…’

Guilt squeezed Isabelle’s heart with a hot, sticky hand. When she started her degree, Dad insisted he would pay, not wanting her to end up with a huge student loan. He bought her a car too.

‘You think I should help out more,’ she said. It was a statement, something she knew to be true. But work placements on hospital wards for up to three months at a time made it impossible to find even a part-time job.

‘I worry that he’ll make risky business decisions.’ Nick was clearly trying to be honest without being unkind. Isabelle’s mum was a quiet ghost present in the room – her death when Isabelle was small was the reason Charles was extra-protective of his daughter. ‘If you … I don’t know … told him you wanted to take care of yourself from now on…’

Isabelle felt a surge of outrage – but it was only guilt. Nick was right. She was lucky that her dad had made it possible for her to do her nursing degree without financial worry. Not many students had that privilege. She felt guilty now that she had waited so long, not enrolling at university until she was twenty-six. Having a dad who kept her, who gave her ‘odd jobs’ so she felt she was ‘contributing’, had made her lazy. Money makes life easy. It means freedom. Now, she works hard for her degree, trying to prove to herself that she deserves to be doing it.

When Nick had gone, Isabelle blinked back tears. She should do more. But what? And how could she fit it around her studies and work placements?

At university the next day, she couldn’t concentrate. The lecturer went on and on and on, but the words Isabelle heard were not 22about co-ordinating care with confidence, they were Nick’s words last night. Take care of yourself from now on. How did the other student nurses manage? Allie, another mature student, said her debts were piling up because there simply wasn’t a part-time job that paid enough and fit around the long hours she had to do in the hospital as part of the degree. Isabelle knew two girls who worked in a lap-dancing club. One of them, Erica, said she only had to work two nights to make over four hundred pounds.

Could Isabelle do that?

No. She was too shy to go on a stage. And she couldn’t dance.

As she tried to take notes, and the lecturer went on and on and on, Isabelle recalled a conversation she’d overheard in the university café. She hadn’t known the girls; one was telling the other about her work as an escort. ‘You don’t have to have sex,’ she was insisting, clearly trying either to persuade her friend to do it too, or perhaps to justify her own choice. ‘Many of the men just want company. It’s easy money, and a free night out, really. I mean, think of the men we date who we wish we hadn’t. With escorting, you choose – and you’re getting paid for it.’

At the time, Isabelle had wondered if she was prudish for feeling repulsed at the idea of taking money for being with someone like that. Then she felt unkind, judging a woman she didn’t even know. How dare she, in her lucky position of not needing to do it? Back in the lecture hall, she thought could she do something like that to take the pressure off her dad?

No. No.

In the weeks following Nick’s disclosure, life seemed to continue as normal. Isabelle’s dad was more like his usual self. Nick never again brought up the matter of money. How easy it was to let herself believe that all was OK, that the casinos were doing well again, that the dad who had always taken care of her still could, for now, until she qualified.

Then, three months later, came the fall.

Then, three months later, came the moment Isabelle really had to step up.

6

ISABELLE GETS HERSELF A NIGHT OFF

Now, Isabelle picks up a stocking, ready to go and visit Dr Cassanby.

They are more expensive than the ones she wore when she started escorting. Not only because she can afford better now, but because in finer clothes she gets a better class of clientele, and therefore meets more of the cost of her dad’s care.

Slipping the sheer silk over flesh, forming a darker skin, she begins the real transition from student nurse to escort. She would far rather finish writing her note or go and talk to her dad for a while, but longing is fruitless. If she doesn’t work, she won’t be able to keep him at home.

As Isabelle takes the second stocking from the bed – it’s snagged, too torn for last-minute disguise with clear nail polish – the phone buzzes and she answers, hoping for the hundredth time that Dr Cassanby is dead.

It’s Gina, the owner of Angels Escort Services.

‘Hey, girl,’ she says in her always-chirpy manner. ‘You’ve got yourself a night off.’

‘Really?’ Isabelle clutches the torn stocking to her chest. ‘How?’

‘You may be happy to hear that Dr Cassanby has explosive diarrhoea.’

Isabelle laughs. ‘He said that?’

‘Haha. No, not exactly like that. He said he has a terrible tummy bug. But that’s what he meant.’

Isabelle likes that calls go through the agency; bookings are always made via Gina. It’s a way to keep things professional, stops new clients harassing the girls directly, and to end things more easily if needed. 24

‘While I’ve got you, I have a new client who’ll be perfect for you,’ says Gina. ‘He’s called Simon and he’s a little shy, poor lad. Has quite a stammer.’ Isabelle is often selected for the insecure clients; she has a reputation for being sensitive to their needs. ‘He inherited a fortune from his uncle, who’s big in the local cleaning industry, so he has plenty of cash, girl. I’d give him the GFE.’

GFE is the Girlfriend Experience; the client wants sex where both the escort and the customer engage in reciprocal sexual pleasure, where there’s emotional intimacy. Isabelle has been surprised by how many men want this – even more surprised by how many believe it to be real affection, despite paying for it.

‘I know you’ll be nice to him,’ says Gina.

Isabelle prefers clients who want their hearts massaging more than their bodies. Sometimes she wonders about setting up an agency of her own, one that’s for the lonely, for the men – and occasionally women – who need a shoulder to cry on. But the Samaritans are there for that, and they’re free. Who would pay hundreds of pounds to be consoled? One of Isabelle’s clients – Jim, who knows she’s a student – often says that she’ll make a wonderful nurse.

Suddenly the young man from the clinic earlier pops into Isabelle’s head.

A beautiful face. Mass of curled hair. Goggles. What was his name again?

Sebastian.

That was it. Sebastian who lent her his goggles so she could see the world through his eyes. Sebastian aged twenty years and six months and two days, as he proudly reminded them. Sebastian who asked if they were going to have sex when they went to see the fish while his mother spoke privately to Mel Cleary, the sexual-health worker.

Currently on placement for two weeks at Rowan House, Isabelle has been shadowing Mel, who she frequently thinks is in entirely the wrong job. It occurs to her now that in such a situation escorts, really, are in the best position to share advice. 25

She had wanted to tell Sebastian that sex wasn’t all that. Sex was simply a physical action. A putting of one thing into another thing. A coming together for relief. And that she, despite her multiple experiences, was yet to have an orgasm. Was yet to feel something more than just flesh. Was yet to know the mystical experience that those who love someone with all their heart experience. She’s had the odd boyfriend – one, Steve, for almost six months – but she ended things each time because she simply hadn’t felt anything close to love.

‘Are you free to meet Simon next Wednesday evening?’ asks Gina.

‘Simon?’ Isabelle tries to remember their conversation.

‘The guy with the stammer.’

‘Oh. Yes.’

Isabelle looks in her diary. She really could do with revising that night. Her university coursework is getting intense now she’s in the final year. But she can’t turn down the money.

‘What time?’

‘Seven. I’ll email the details over. Enjoy your night off.’

‘I will.’

Isabelle hangs up and flops on the bed, one stocking on and the other in her hand, topless and exhausted, which she muses is odd when there isn’t a client fastening his trousers nearby. Though she feels sick at losing four hundred pounds, she decides she can work extra next weekend to make it up.

How quickly she went from judgement to acceptance – from thinking she could never do something like this to realising that it was the only option. Was it fast? Not really. A month perhaps between the fall and her first client. A month in which she learned just how much it would cost to take care of her dad. A month that began with breaking down in tears while speaking to fellow student Erica about what lap dancing was like (exhausting) and ended in Gina’s Angels Escorts Services office, for an interview.

It was the first time she’d ever had one in a room with leather wallpaper and boxes of dildos on an expensive-looking black desk. 26Gina was Erica’s aunt, and shared her forthright manner and warm smile. She wore a tailored black suit, and had smooth hair, which surprised Isabelle. What had she expected? Brassy? Brash?

‘I don’t even know if…’ Isabelle had stammered, looking at the door, just wanting to go home.

‘If you want to?’ Gina spoke kindly. ‘But you need to, yes?’

Isabelle nodded.

‘Most of our clients are just lonely,’ said Gina. ‘It isn’t always about sex – many just want someone to listen to them, and you’ll make the same money lending an ear as you will doing anything else.’ She insisted that enjoyment of sex was not a prerequisite for the job – nor was being good at it, though that did help – because an escort sells her time, attention and entertainment. She explained that this role was not prostitution, where only sex is given for money, but far more, and many of the women were proud of what they provided. A client might just want a dinner date or a travel companion, nothing more. ‘My girls put as much passion into conversation – into listening and being there – as anything else.’

Isabelle could do that couldn’t she?

Lend an ear? Listen?

Yes. She would have to.

And she did. That was all she had to do with her first two clients, a seventy-year-old man who craved company and talked of his days in the army, and a younger man who needed her to accompany him to an office event, and who merely thanked her when it was over.

By the time she met her third client, Dr Cassanby, Isabelle had seen the money. She had been able to pay some of her dad’s care bill. She had been able to take care of him the way he had always taken care of her. And there was no going back from that.

7

MEET ISABELLE’S THIRD CLIENT – DR CASSANBY

The doctor was Isabelle’s third client and had been the most demanding so far, despite having specified that he required only companionship, intelligent conversation and the occasional evening out.

One October evening three months ago, he opened the doors of his five-bedroom, Grade II listed home in Kirk Ella and invited Isabelle into an imposing hallway and then the lounge. Despite the simple requirements he’d given, she half expected to see cameras or chains dangling from walls, and was relieved that there were just three cream sofas and a coffee table supporting neat rows of Capital Doctor magazines.

Cassanby was in his late fifties or early sixties, and well groomed, with distinguished black-and-grey hair, snarled eyebrows above steely blue eyes, and the air of a man who got whatever he wanted. He certainly wasn’t unattractive, and Isabelle often wondered why he needed to pay anyone. Was it the thrill? The control? Was it that he was guaranteed to get exactly what he desired?

A distinct absence of family photographs or abandoned shoes in the hallway suggested that this barren but beautiful house was occupied only by Dr Cassanby. Isabelle wondered briefly if he was divorced or just a loner. A man of his obvious wealth certainly wouldn’t find it hard to pick up a gold-digging wife.

‘Can I take your coat?’ he asked in a husky voice that she assumed was an attempt to be seductive. This confused her. He didn’t need to persuade her; he was paying. ‘What’s your name?’

Observing Gina’s advice that it separated the escorting from everyday life, Isabelle had chosen another name, Violetta. She said 28