1,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Thrilling

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

It’s hell to be told 37 is too old to fly the void when you know where a great treasure lies. The Captain Future saga follows the super-science pulp hero Curt Newton, along with his companions, The Futuremen: Grag the giant robot, Otho the android, and Simon Wright the living brain in a box. Together, they travel the solar system in series of classic pulp adventures, many of which written by the author of The Legion of Super-Heroes, Edmond Hamilton.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

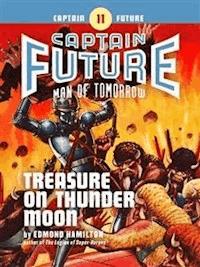

Treasure on Thunder Moon

Captain Future book #11

by

Edmond Hamilton

It’s hell to be told 37 is too old to fly the void when you know where a great treasure lies!

Thrilling

Copyright Information

“Treasure on Thunder Moon” was originally published in 1942. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Chapter I

The Company

“MAYBE there’s a chance,” John North thought desperately. “If they just don’t think I’m too old—”

North’s small, compact figure, shabby in a frayed black synthe-wool suit, threaded between the docks of towering space liners and through hurrying officials, swaggering young spacemen, and sweating porters, until he reached the impressive offices of the Company.

The operations office of the Interplanetary Metal and Minerals Company, that giant corporation known everywhere as simply “the Company,” was a massive block of glittering chrom-aloy. Beyond it lay the towering warehouses and docks and cranes that handled the cargoes from other worlds.

John North paused outside the entrance to inspect his reflection in the polished metal wall, earnestly smoothing his worn jacket. His heart sank as he looked at his own image. His dark hair was faintly thin at the temples, his black eyes had tired lines around them, his tanned face looked thin and pinched and old.

“Thirty-seven isn’t old!” he told himself fiercely. “Even for a spaceman, it’s not old. I’ve got to look young, feel young!”

But it wasn’t easy to feel young, with the hunger he had felt all afternoon gnawing at him, with foreboding of failure gripping him, with his shoulders sagging from twenty years of toil and hardship and heartbreak.

“Straighten up—that’s it,” North muttered. “Look spruce, alert, efficient. And smile.”

Yet he couldn’t keep the mechanical smile on his drawn, old-young face as he made his way through busy chrommium corridors to the office of the new operations manager. He waited there for what seemed an eternity, fighting the hunger-born dizziness that threatened him. At last he was admitted.

Harker, the new manager, was a gimlet-eyed, tight-mouthed man of forty who sat behind a big desk reading off a materials list to a respectful young secretary. He looked up impatiently when North nervously cleared his throat.

“John North, sir, applying for a berth,” North stated, trying to look the picture of a clean-cut efficient spaceman. “I’m a licensed S.O.”

“Space Officer, eh?” said Harker. “Well, we can use a few good pilots now on the Jupiter run. Let’s see your certificate.”

It was the moment North had dreaded. Slowly he handed over the frayed, folded document. His shoulders sagged slightly as he waited.

The manager turned the frayed certificate over, his gimlet eyes starting to read the service-record on its back. He looked up suddenly.

“Thirty-seven years old!” he snapped. He tossed the document onto the desk. “What did you come in here for? Don’t you know that the Company never hires a man over twenty-five?”

John North tried hard to keep his mechanical smile. “I could be valuable to the Company, sir. I’ve had twenty years space experience.”

“That’s fifteen years too much,” answered the manager brutally. “A spaceman’s washed out at thirty. He doesn’t have the coordination, quickness of reaction or alertness of a younger man. We don’t trust our ships to worn-out, middle-aged men who can’t meet emergencies.”

John North felt his faint hope expire. This new operations manager had the same viewpoint that all the others had had.

The young secretary was looking curiously at North. “You went to space twenty years ago? Why, that was in the earliest days of space travel. Half the planets hadn’t even been visited, then.”

North nodded dully. “My first voyage was with Mark Carew on his third expedition, in ’98.”

“And I suppose you think you’re entitled to a big job because you were a hero twenty years ago?” demanded Harker hostilely. “That’s the trouble with all you older spacemen. You think because you happened to be on the first exploring expeditions, because you got a lot of publicity and hero-worship then, that you all rate captain’s comets now.”

“But I don’t ask for a captain’s berth,” North protested. “It needn’t even be an officer’s post. I’ll take any job—a cyc-man, a tube-man, even a deck-hand.”

He added in strained appeal, “I need this job, a lot. And space-sailing’s the only trade I ever learned.”

The manager snorted. “Too bad for you, that you didn’t learn another trade. Anyway, even if you were young enough, the Company wouldn’t want you. The old careless ways of you early spacemen are out, these days. Ships are operated scientifically now, with none of the hell-raising hit-or-miss tactics of you old timers. Things have changed.”

North bit his lips and looked out of the window to repress his feelings. His tired eyes fixed on the soaring metal shaft that rose in the sunlight beyond the square bulk of the Company’s warehouses.

It was the Monument to the Space Pioneers, that marked the spot where Gorham Johnson had returned from the first epochal space voyage years before. North’s mind went back to the day when he himself had come back with Carew and landed there, the madly cheering throngs, the sententious speeches.

“Yes,” North said dully. “You’re right. Things have changed.”

HE went out of the building blindly, clutching his useless certificate. Out in the sunlight and bustle of the spaceport, North paused.

The Venus liner whose big cigar-like bulk towered from its dock nearby was making ready for take-off. He could hear the staccato thunder of its tubes being tested. Passengers and porters and gray-jacketed Company officers were hurrying toward the ship. A few bewildered Venusians, white-skinned, handsome men, and one or two solemn native red Martians were in the throng. A band was beginning to play a gay, lilting tune.

North could remember when this had all been a bare field, twenty years ago. There had been nothing here then but the ramshackle hangar in which a score of eager young men had worked with crippled, indomitable Mark Carew to prepare an absurdly small and clumsy ship for the great voyage that was to add Saturn and Uranus and Neptune to the list of visited planets.

That was his trouble, North thought bitterly. He was always living in the past, the times twenty years ago when the world was young and the sun was bright, and all Earth was cheering him and his friends to new pioneering exploits.

“I’ve got to forget all that,” he told himself heavily. “I’ve got to quit brooding on the past. But what am I going to do?”

He hated to go back to the shabby rooming house over on Killiston Avenue. Old Peters and Whitey and the others were hoping so fervently that he’d be able to get a berth today. They all needed the money so badly.

He shrugged wearily. They’d have to learn the bad news some time. He plodded off the spaceport, his slight, shabby figure unnoticed amid the excited, gay throng that had gathered to witness the take-off of the liner.

Killiston Avenue was one of the ruck of shabby streets around the spaceport. Its drab spacemen’s lodging houses, drinking joints and cheap restaurants huddled like disreputable dwarfs under the shadow of the Company warehouses. North turned in at his own lodging house and tiredly climbed the dark stairs to the dusty garret which he and his comrades had shared for six months.

North found some of the others already there. Old Peters was there, of course, sitting in his makeshift wheel-chair and peering across the huddled roofs at the thunderous take-off of the Venus liner. He turned his white head.

“That you, Johnny?” he shrilled, his faded eyes peering. “I was just watchin’ that liner blast off. Sloppiest take-off I ever saw!”

The old man quavered on. “Cursed if these young spacemen don’t get worse every day. You ought to have seen the landin’ the Mars mail-boat made this mornin’. Why, when I was rocketin’, anyone who made a landin’ like that would have been kicked off the spaceport.”

North assented absently. He was used to old Peters. The old man had not been in a ship for fifteen years, but still never tired of dwelling interminably on the old days.

“We wouldn’t have stood for such spacemanship,” he grumbled on.

North turned. Steenie was coming up to him. Steenie was forty three, but he had the smooth face and bright blue eyes of a boy of fourteen.

“Do we take off again tomorrow, John?” he asked North eagerly.

“Not tomorrow, Steenie,” North answered gently. “Maybe the next day.”

And Steenie went back to his chair in the corner and sat smiling vacantly at them. He had smiled that way for years, ever since he had come home from Wenzi’s last voyage, a space-struck mental wreck.

JAN DORAK came up to North. A dark, heavy, stolid ex-spaceman, he looked inquiringly at North’s drawn face.

“Any luck, Johnny? The new Company manager—”

“Is like all the rest,” North answered wearily. “I’m too old.”

The others were drifting in—Hansen and Connor and big Whitey Jones. They had heard his words.

“Never mind, they’ll have to call us in someday soon,” muttered stocky Lara Hansen confidently. “They’ll find out they need us old-timers.”

“And anyway, I got a little job today and we’ll eat tonight,” declared Mike Connor. “Look, fellows—grub and synthebeer for everybody.”

Connor’s battered, merry red face was carefree as always as he showed his packages. Connor never had worried about anything, not even as Carew’s third officer on that disaster-ridden second voyage long ago.

But big Whitey Jones, a shock-headed blond giant of forty, slapped North’s back sympathetically with his left arm. Whitey’s right sleeve hung empty and had hung that way since a tube-explosion years ago on Wenzi’s ship.

“Too damned bad about the new operations manager, Johnny,” he rumbled. “I was hoping he’d give you a break.”

“Company rules don’t change, it seems,” North muttered. “A man over twenty-five hasn’t a chance to be signed on.”

“Hell take the Company!” growled Whitey. “As if you weren’t a better spaceman than the half-baked kids they’ve got running their tubs.”

North made no answer. What was the use of going over all that again? The others were blind to the changes that had taken place. They still thought of themselves as the pioneering young spacemen who had sailed with Johnson and Carew and Wenzi and the other great first explorers who had opened up the spaceways in their epochal first voyages to other planets.

But all that had been a generation ago. Everything had changed, since then. Interplanetary navigation had mushroomed from that precarious beginning into a vast, profitable trade. The rush of ambitious Earthmen to other worlds, the scramble for valuable metals and minerals on foreign planets, had caused space-shipping to expand with incredible rapidity.

And in that explosive expansion the early space pioneers had been forgotten. They had been famous for a short while—but fame was ephemeral in these swift-moving times. And very many of them had died from the hardships of the early voyages in unsafe, ill-equipped, primitive ships. The great Gorham Johnson, the first space-voyager of all, had died in his third voyage off Jupiter. Mark Carew, his famous successor, had gone two voyages later. Wenzi hadn’t long survived his pioneering trip to Pluto. From ray-burns or internal injuries or weakened hearts, the space pioneers had dwindled away.

And those who survived were nearly all in straitened circumstances. That had been more or less inevitable. They had been spacemen, their only interest the pioneering of space travel. They therefore reaped no riches from the worlds they opened up. It had been the prospectors, and speculators and promoters who came after them, who eagerly staked claims to every valuable metal deposit on the planets, who reaped the reward. And the richest reward of all went finally to the astute Earth financiers who formed the giant Interplanetary Metals and Minerals Company, which bought or otherwise absorbed its smaller competitors until it dominated all interplanetary shipping and sucked profits from mines on every world.

Aging, poverty-stricken, deemed unfit now for the space-sailing that was their only trade, this dwindling remnant of the space pioneers had clung together. By pooling their scanty earnings at odd jobs, they had kept alive and hoped for a chance to get to space again. But now the last hope of John North and his comrades seemed definitely ended.

“It’s a damned shame, for the Company to keep you earthbound,” Whitey Jones repeated. “Just because you’re a few years older than a boy.”

“They’ll be asking us to come back some day,” affirmed Hansen dogmatically. “They’ll find they can’t do without the old-timers.”

“What’s keeping that crazy Connor?” demanded old Peters querulously in his shrill voice. “I’m hungry and I want my supper.”

“Keep your shirt on, you old rascal,” came Connor’s blithe voice. The battered ex-officer was putting cracked dishes on the table. “Come on!”

They ate hungrily in silence, and then opened the synthetic beer. A faint glow lighted the shabby company as they sat over the glasses, and talked the latest space-gossip, of ships reported missing, of a record run from Mercury, of the Company’s latest financial piracy on Jupiter.

THE talk shifted inevitably back to the old days, as it always did. “I remember when—” “Say, do you remember that time when—” Old names of a generation ago passed freely back and forth. Old Peters crushed down all opposition to his shrill, authoritative pronouncements.

John North listened tonight with a sense of gray futility. He knew that they were all just trying to convince themselves that they were still of importance, trying somehow to recapture a little of that lost glory of the past, of youth. But tonight he could not fall in with it.

Whitey turned from a hot argument with Connor to ask him, “Johnny, this crazy Irishman says that Carew could have made Pluto if he’d pushed on in that third voyage. I say he’s cuckoo. What do you think?”

North answered bitterly. “I think we’re all ghosts, arguing over shadows.”

They stared at him amazedly. But the bitterness that North had felt all afternoon was now breaking its bounds.

“What good does all this talk about the past do us? What difference does it make what we did twenty years ago? The world’s forgotten all that. And we’d better forget it. We’d better forget all about space-sailing, and try something else!”

Whitey answered bewilderedly. “But we don’t know anything else but space-sailing.”

“We can be gardeners, laborers, anything,” North flared, getting to his feet. “It’d be better than always living in a forgotten past.”

Then he felt swift contrition as he saw Peters’ blinking stare, the faint distress in Steenie’s vacant eyes, the heartsickness in the faces of Whitey and the others.

“I’m sorry, boys,” North muttered, turning away. “Just blew my tubes, I guess. I’m going out for a breath of fresh air.”

He flung open the door, then stopped short. Outside the door stood a girl in a smart white synthe-silk dress, who had just been about to knock on their door.

She uttered a little breathless exclamation of surprise. “You startled me—”

North eyed her. She was young, tall but with a faint awkwardness of immaturity that somehow had a charm. He got an impression of dark hair, candid brown eyes and parted red lips.