Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

Professional Storyteller Wendy Shearer has gathered together stories from many Caribbean islands and countries, drawing on oral history and written texts to bring these folk tales to life. Many stories are of West African origin, kept alive through rhythm and song. These tales and their languages were blended with European and East Indian folklore, with royalty, heroes and spirits exacting revenge. Alongside the stories are newly collected reminiscences of migration to Britain from Caribbean countries during the Windrush years. These first-hand accounts mirror the themes found in the folk tales with love and loss, magic and mystery, caution and justice. Cric! Crac! Prepare to be enchanted by La Diablesse from Haiti, outsmarted by the trickster Anansi, or terrified by the shapeshifting Old Higue in Guyana.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 233

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2022

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Wendy Shearer, 2022

Illustrations © Markio Aruga

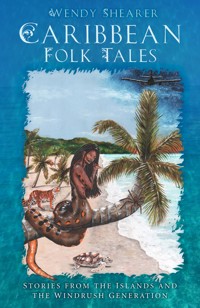

Front cover illustration © Jenna Catton

Text and photograph of the Bearded Fig tree by Wendy Shearer

Sketch of Mary Seacole © Crimean war artist William Simpson c. 1855

The right of Wendy Shearer to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 8039 9077 4

Typesetting and origination by The History Press.

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword

Acknowledgements

Introduction

GRACE HALLWORTH, TRINIDAD

EULINE STEWART, GUYANA

SPIRITS & SHAPESHIFTERS

La Diablesse (Martinique)

The Shapeshifting Hog (Trinidad)

The Old Higue (Trinidad)

All That Glitters (Guyana)

The Curse of Mama D’leau (Trinidad)

WINSTON NZINGA, JAMAICA

ELMA HOLDIP, BARBADOS

MUSIC & SONG

The Singing Bones (Haiti)

When the Paths Vanished (Cuba)

The Guitar Player (Grenada)

The Singing Sack (Guyana)

Dance, Granny, Dance (Antigua)

PATSY KING, JAMAICA

TONY LIVERPOOL, DOMINICA

TRICKSTER TALES

How Turtle Fooled Rat (Guyana)

Anansi and Mongoose (Jamaica)

Fowl & Hyena (Jamaica)

Anansi, Tiger & the Magic Stools (Jamaica)

Nangato the Cat (Puerto Rico)

Anansi and Fire (Jamaica)

ROSAMUND GRANT, GUYANA

BARBARA GAREL, JAMAICA

LOVE & LOSS

The Legend of the Giant Water Lily (Guyana)

The Fairymaid’s Lover (Trinidad)

The Poisoned Roti (Trinidad)

The Legend of the Hummingbird (Puerto Rico)

ALMA CLARKE, BARBADOS

TALES OF CAUTION & JUSTICE

You Reap What You Sow (Trinidad)

The Three Figs (Barbados)

No Justice for the Devil (Suriname)

Mary Seacole

Bibliography

FOREWORD

Whether it is the suspense aroused by watching an unsuspecting young male being lured away by the hypnotic powers of the legendary La Diablesse or the feeling of victory experienced with the discovery of the deceptive plan of ‘the shapeshifting hog’ who attempts to trick a young girl from a small village into marrying him, this collection of stories by Wendy Shearer will produce nostalgic moments of humour, reflection, and cultural connection for Caribbean readers across the globe. Caribbean Folk Tales: Stories from the islands and the Windrush Generation is a stimulating and thought-provoking creative collection which introduces readers to the rich, diverse culture and heritage of the Caribbean region.

The distinctive value of this collection lies in its ability to fuse together past and present worlds, unite different generations of readers, and celebrate the strong influence of Afro-Caribbean spirituality in the lives of Caribbean people. The collection offers an energized sense of continuity through the thematic placement of the different stories and through the sustained presence of orality established across each storytelling episode, showcasing the similarities which unite those from the Caribbean and the differences which cause each island to be unique. Through the invocation of a distinctly creolized set of voices and narrative style, Shearer artfully articulates stories involving legends, magical realism, songs, and proverbs which pull us back into a past lined with a rich Caribbean oral tradition, and place lessons at our fingertips, which we can readily access and appropriate to navigate our present-day realities. This Caribbean flavour is further enhanced by the presence of universal themes, such as the struggle of good versus evil, the plight of love, appearances versus reality, and the fight for freedom, which can be appreciated and enjoyed by readers across diverse cultures and ethnicities.

The ancestral practice of storytelling is presented throughout this collection as an act and process which restores, heals, and nurtures. The collection balances fiction with non-fiction through both the morals embedded in the folktales in each chapter, and the presentation of autobiographical narratives from members of the Windrush generation through their personal and historical accounts of migration, memories of their homeland, and their participation in specific cultural practices. The folkloric frame used to characterize the tales in each chapter removes this genre of orality from the marginal places it tends to occupy in Western literary culture and emancipates the dominant historical narratives of some of the Caribbean mythical figures often defined in past European literary traditions as barbaric and soulless. Shearer’s stories reposition these characters, so that their representation in this collection, now present them as heroes, heroines, or the figures who ‘will disturb their neighbours’, to use Bob Marley’s description of referring to a personal act of activism which will emerge from an inner awakening and affect the entire community. The stories in this collection can be seen as significant artifacts which represent, affirm, and celebrate Caribbean identity and consciousness, especially in the face of racism, sexism, and issues of cultural prejudice in diasporic spaces. Additionally, the stories also subtly address patriarchal and stereotypical notions of identity and behaviour, subverting and challenging dominant ideologies that may have tainted some of the earlier accounts of these original, oral folktales.

Shearer’s stories bring Caribbean legends and myths to life through the creative construction of different versions of these oral folktales adapted and retold in ways that provide valuable information about the histories, identities, and traditional practices of Caribbean people. By reshaping many of these well-known Caribbean myths, Shearer promotes the view that these tales are not to be characterized as mere superstition but instead to be hailed as coming through a storytelling pathway deeply embedded in the realm of the supernatural.

The collection fuses together an older, traditional folktale style with a more modern representation of voice and context where certain stories come to us through the rare use of the second person narrative voice which beckons the reader to be a part of the tale and to explore the magical worlds of the characters and settings present, establishing the call and response technique indicative of Afro-Caribbean culture. Shearer creates an authentic experience for her readers through the detailed depictions of the many and varied Caribbean tales that have been such a significant part of the lives of Caribbean people over centuries, In the chapter Music and Songs, for example, we are softened by the presence of tragedy in stories like The Guitar Player, where a disheartened guitar player’s ghost exacts revenge for the disregard he experiences at the hands of his community, while simultaneously we are moved when our sensibilities are awakened to the beauty of the musical rhythms and moments of dance.

Readers of this collection will be emboldened and inspired through stories of courage and bravery where the silenced or downtrodden right wrongs and disrupt acts of exploitation through skilful tactics and shrewd mindsets. Each of the stories presented in this collection sensitizes readers to the ways identity is deeply intertwined in the historical process of each Caribbean region and immediately connects readers with the full details of mythical characters, snippets of stories, and imagined worlds they are likely to have heard about through their parents, grandparents and/or great grandparents. Some of the fairy tales and legends remind us of virtues like patience, tolerance, and trust, while the cautionary tales encourage the celebration of a spirit of resilience and strength in the face of hardships and injustice.

The representation of Caribbean folklore and the unique presentation of Caribbean voices from the Windrush generation as part of the overall presentation of the stories in this collection, offer both young and old the opportunity to engage in a more personalized and sustained way with various aspects of Caribbean folklore and history. The stories here invite us to witness and participate in the enchanting and unforgettable worlds and encounters which have helped to shape Caribbean culture and experience. Open your minds and get ready to experience how something old can also become something new!

Dr Aisha T. Spencer, Phd

Senior Lecturer, Language and Literature Education, University of the West Indies, Mona

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A huge thank you to all the people from various Caribbean associations and friends who shared their personal stories and folklore with me, especially Rosamund Grant, Grace Hallworth, Winston Nzinga and Baden Prince.

Thanks also to Dr Philip Abraham, Caribbean collections expert within the Eccles Centre for American Studies at The British Library and Dr Aisha Spencer from The University of the West Indies.

Friends and family: Mum (Euline Stewart), Nan (Cleo Taitt), Uncle Maurice Taitt, Naomi Conroy-House, Gary Baron, Gary Bailey, Giles Abbott, Pippa Reid and especially my husband Matt Shearer, for their support, memories and introductions to their friends and family.

And thanks to illustrators Jenna Catton for the front cover and Mariko Aruga for the black and white illustrations throughout the book.

INTRODUCTION

Here you’ll find a collection of folk tales and legends from a variety of Caribbean islands and mainland countries of Guyana and Suriname. The tales include stories of characters unique to each island, historical figures like Mary Seacole and legends of indigenous people – the Caribs and Tainos, who lived on the islands before European conquests. I’ve adapted these stories, and set them in the landscape of each island’s history and culture where the wildlife and plants feature as important characters in their own right. Some stories are old and some are new, and most have been carried to the islands by enslaved Africans and blended with European and East Indian folklore. They’ve grown and transformed with each telling, reflecting cultural rituals that I’ve been introduced to by my Guyanese parents and grandparents.

The stories are usually told outside in the evenings on the islands, when old and young people gather together, always with rhythm and song. In this way, they continue the role of the African Griots who, for centuries, have been known to be the travelling storytellers and oral historians, preserving history and traditions.

I have arranged these folk tales into themes that reflect Caribbean culture, history and spirituality: Spirits & Shapeshifters; Music & Song; Tricksters; Love & Loss; and Caution & Justice. Many versions of these stories exist across different islands. You will meet the ‘jumbie’ spirit from Guyana, known as a ‘duppy’ in Jamaica, and the ‘ol Higue’ from Trinidad, known as the soucouyant in Haiti, who sheds her skin at night and transforms into a ball of fire, seeking out her victims. You’ll also meet the renowned trickster Anansi, who began his journey with the Ashanti people of West Africa, considered to be the spirit of all knowledge and the keeper of the stories. In Caribbean folk tales he wilfully sneaks into situations, entering into the animal and human worlds where there are no boundaries; finding himself in trouble that he can often overcome.

Before each chapter I have included personal accounts from people who I have interviewed to capture their recollections of storytelling while growing up in the Caribbean, and their memories of leaving their island countries and arriving in the UK as a child. They migrated to England from these islands during the Windrush years and came to join their parents who were already in the UK working as nurses, bus drivers, engineers and construction workers. Many of them came to carve out a future for their families or to answer the request from the government to help rebuild Britain after the Second World War.

These oral histories are filled with bitter-sweet memories of leaving their Caribbean homes and embarking on a new life. Some of their childhood memories link to the themes of the folk tales where they were imagining smog-filled London crawling with spirits, loving the adventure of a new country, sad at leaving their old home or experiencing racial injustice in their new one. I spent many hours listening, documenting and travelling back in time with them. I feel incredibly privileged that they were happy to share their thoughts with me. The process itself of capturing their words was cathartic for those who had not shared these anecdotes before. Everyone recalled how oral storytelling was an integral part of their family life in the Caribbean.

The spirit and culture of black people are carried in the stories and songs, travelling across the islands and to the UK – wherever anyone goes. Despite the displacement of black people across countries, the stories are still passed down by generations, reflecting society and carrying wisdom.

Wherever we go, the stories go too.

GRACE HALLWORTH, TRINIDAD

Grace Hallworth was a storyteller, librarian and author from Trinidad who published eighteen children’s books. She appeared at many international festivals, on radio and on television, and served on a number of children’s literature award panels. Her many books include Down by the River, illustrated by Caroline Binch, which was a runner-up for the Kate Greenaway Medal in 1996. Grace had been the first Chair and long-standing patron of the Society for Storytelling. Sadly, she died in August 2021. She was a marvellous inspiration to children and adults who had the pleasure of hearing her vibrant voice bringing stories to life or reading her wonderful Caribbean folk tales and songs. When gathering stories for this book, I contacted Grace and she welcomed me into her home. We sipped ginger and apple juice, and in between tales, she shared memories of how she came to be in the UK.

My storytelling journey began when I received a scholarship for Boys and Girls House in Canada. They empower young people and help develop their skills. I was 22 years old. It was in Canada that I found out, they were noted for storytelling. Eileen Colwell, who pioneered the children’s library, and later founded the Association of Children’s Librarians, was there too. They all fell in love with her because they had not seen anybody so involved and passionate about storytelling. I was lucky to end up at Boys and Girls House. I discovered the power of storytelling and stories there. I always enjoyed storytelling at home in Trinidad but there I found out what a powerful medium of communication it is.

Every Monday at Boys and Girls House, you had to present any book that you found interesting. I also told stories and they encouraged me to do that. That’s how I began to take it seriously. In Trinidad, we told stories all the time, but no one really took me seriously. I was just ‘Grace telling stories’. In Canada, they thought of it as having a serious power. Canada was the real start of my storytelling journey. During that time, I came over to Leeds in England to visit my friends and tell stories. It was my first visit to the UK. I liked it and enjoyed being here. I received a warm welcome from people and they wanted me to stay, but I was still in the middle of my scholarship and had to return to Trinidad for a short while.

Soon afterward, I was invited to Hertfordshire in England to develop children’s literature and storytelling in libraries. They were very keen for me to come. Everything in the UK was moving in the direction that I wanted to go. I was also doing a lot of work with primary and secondary schools. I started as a Children’s librarian and then I was promoted to Divisional Schools librarian. Soon my work expanded to other places, including general adult libraries and hospitals. Once they heard that I was telling stories, they wanted me too. The momentum was building.

Soon after that, Ben Haggarty and I got together and we formed a society for storytelling. We were extremely keen to do this and knew that we needed to invite storytellers from other places, festivals, theatres, and all kinds of events. This was a new chapter in my storytelling journey. You might say that I was fortunate in that everything worked in my favour.

EULINE STEWART, GUYANA

Education and Mediation Consultant

I came to England in 1964 with two of my younger brothers. I was 12 years old and we flew on the British Overseas Airways Corporation flight, better known as BOAC. Our neighbour was also travelling to England on the same flight with her two daughters and she had agreed to be the guardian for my youngest brother, who was 4 years old at the time.

We never came to England together as a family. No families did at that time. My dad came first, arriving in 1962, and then once he had managed to find a decently sized house for us, he sent for my mum, who came in 1963. The rest of us remained living in Guyana with our grandparents, while my parents were working in England. Before emigrating to London, we had all lived together as a family in one big house in West Ruimveldt Housing Scheme and so it didn’t feel unusual when our parents left to travel and live abroad because we were still with my grandparents. However, we were separated as a family for a total of two years.

I was so excited about coming to England, because as children we were told the streets were paved with gold and that there was no mud! I was expecting it to be so sunny and clean, just like it was in Guyana. I arrived on 31 October 1964 (late into the evening) and it was extremely cold, dark, foggy and snowing. I remember the street lamps had a yellow glow and looked very dim, which made me feel very unhappy. This was the first time I had seen snow. The fog was so intense that I could hardly see anything in front of me. We’d never seen that before and we definitely didn’t see any gold on the streets! London seemed very weird to me as a child. When we were walking on the pavement, we’d see people walking out of their basement house in the midst of the fog as if they were rising like jumbies (ghosts) from the street. I thought this was a bizarre sight to see at the time and quickly hastened my steps and walked as fast as I could.

After a few days of living in London, I wanted to go back to Guyana, because the weather was very cold and I wasn’t used to it. We had to wear gloves (or mittens) on our hands and boots on our feet. Sometimes you couldn’t feel your toes! Your nose and ears would get extremely cold and I began to suffer from nosebleeds a lot! My father told me that ‘I’ll get used to the weather’.

Just before I left Guyana, I had passed my 11+ to go to Bishop’s Girls’ High School. This was the only top girls’ school in Georgetown and I was sad that I wasn’t able to join my friends to attend the school because I was coming to England to join my parents instead. We lived in south London and my dad enrolled me at Westwood Girls’ High School. The teachers immediately placed me in the bottom sets, because they assumed that as I had not been educated in England that I must be backward (a label I later discovered was given to West Indian children as being educationally subnormal). The standard of teaching in Guyana was extremely high when I was living there. My dad insisted that I be tested on the first day of school and I was tested vigorously in what they termed spoken English and maths, which included algebra, fractions, logarithms, measuring various types of angles, etc. I sailed through the tests and was placed in the middle B sets for maths and English. The headteacher was amazed that I had such knowledge in mathematics for my age. After six months, I was moved mid-year up to the ‘A’ stream and remained there until what we now call Year 11. I was the first and only black student in that top set at school.

I enjoyed school and had no problems. My brothers were at the local boys’ school. I remember that the joy of living in London was not hearing the singing sound of mosquitoes or even being bitten by them! They were and still are Guyana’s most common flying insect. I hated them, because when they bit you, the typical reactions to the bite are itching and swelling, which can cause a serious illness such as malaria. Education has remained a really important part of my life. After achieving my M.A. in Education, I have been a mentor for young black and ethnic minority youths, an inclusion officer to prevent exclusions in primary schools and now I am an education and mediation consultant, helping people to resolve conflicts when communication links have broken down.

I did miss gathering together as a family to hear stories when we were in Guyana. Storytelling and folk music was a part of our lives in Guyana. Our grandmother would tell us stories of jumbies and shapeshifters to frighten us as a child at night and stories of Anansi the wise trickster. If any of us told a fib, my gran would say, that’s ‘nancy story you telling me’.

Many Caribbean folk tales are filled with ghosts and magical creatures, reflecting a history of African spirituality and the afterlife. The stories share warnings or moral teachings about life on the islands and these are my versions of a few familiar tales that are told in different ways throughout the islands. Some people believe these events happened or may have partially happened. I’ll let you decide.

LA DIABLESSE

Martinique

Long, long ago, on the Caribbean island of Martinique, the French still ruled and Creole was the spoken word. It emerged from the rich medley of French and African languages, created by the enslaved Africans. On this picturesque island, the mountains would erupt and lava would flow freely into valleys, burying everything in its wake. Hurricanes would rampage through villages, wiping out factories and ripping up trees. With all of these violent horrors lurking among the villagers, it might surprise you to know who they feared most. La Diablesse.

Some people said she was a she-devil. A jumbie with a disfigured foot that resembles a hoof. Others said that she was a witch, roaming the highways alone, waiting to cast her vengeful spells on unsuspecting men. Everyone said to watch out, beware and be on your guard for strangers in your village.

The story goes that on one typically blazing hot day, people were stretched out on their verandas, sighing in the shade. Watching nothing. Imagine a day so hot that even the air is languid, where each breath you take is a slow, dragging movement. Two young men, Kabenla and Ekoux, were sitting outside of their boarding house. They’d stopped for lunch after working all morning at the sugar factory and sat staring into the distance, watching nothing in particular. The sweet scent of mango hung in the air from trees dotted around the houses. Goats ambled across the paths, nibbling at leaves and long grass.

‘Kabenla, you notice how quiet it is today?’ Ekoux nudged his friend. Even though it was the middle of the day, with sunlight exposing every living thing, Ekoux felt a darkness creeping up around them. He glanced around. He had a sense that something was not quite right. Houses seemed hushed into silence with their shutters closed up. Trees appeared monstrous behind him, terror swaying with each branch.

‘Kabenla, did you hear me?’ Ekoux asked his friend again.

‘Ease me Ekoux, can’t you see I’m busy?’

Ekoux followed Kabenla’s gaze. Seemingly out of nowhere in the brilliant light of day, a tall, slender woman was striding through the village. Her pace was at odds with the sluggish heat of the day. Her long arms swayed back and forth, driving her body forward. Her colourful clothes draped unnaturally around her body, stiff and lifeless. She wore a short-sleeved blouse and a long madras skirt that fell rigid to the ground. Glimpses of her white ruffled petticoat could be seen as she glided along. Her face was partially hidden by a wide-brimmed straw hat. She was dark, serene, and heading their way.

‘Look how her hips are swaying. You see her eyes?’ Kabenla said, in a daze. It’s true, she did have the most exquisite-looking eyes but they were not welcoming. They were cold and glassy. Set deep into her face like obsidian rock. She went past the boarding house.

‘Bonjou mesye, hello sir,’ she nodded firmly, without stopping.

‘Bonjou madanm, hello madam,’ Kabenla replied. He jumped up from his seat and quickly fell into step with her.

‘Eh, eh, you look as sweet as molasses,’ he said with a wide grin. She did not reply or even look at him.

And so it begins again. She sighed to herself. She was used to getting unwanted attention from men. At first, she felt flattered by it, as she travelled from village to village, seeking a new home after the loss of her own. Men would compliment her, offer her work on their land, even appear to befriend her. She had been naive but now she could exact her revenge. She carried on striding while Kabenla carried on talking.

‘I’ve never seen you here before. Ki kote ou soti? Where are you from?’

‘Affairs of the chicken are not affairs of the goat,’ she replied, keeping her dark eyes facing straight ahead. She thought Kabenla was the same as all the other men before him. The ones who would look right through her clothes to her dark naked skin. The ones who would undress her in their mind as they followed her every move.

‘Why so serious?’ Kabenla wanted to know.

‘I’m in mourning. I died long ago.’ Perhaps she was just joking or trying to shock. Either way, Kabenla took no notice.

‘Would you like some company?’ he offered, puffing up his chest.

She stopped and stared at him for the first time. ‘Before climbing up a tree, make sure you can climb down.’ Her tone was not unfriendly and yet not quite inviting. Under the brim of her hat, he saw his reflection in her eyes. Those dark eyes.

‘I’m walking up high, where the cinnamon spices grow and the rainfall is plenty,’ her voice seemed to soar right into the mountains when she spoke. Kabenla knew that she was heading far away from his village. He’d never make it back in time for his afternoon shift at the factory. He turned back to look at his friend. Ekoux was shaking his head and waving his arms, signalling for Kabenla to return. For some reason unknown to him, Kabenla felt compelled to go with this woman. He was captivated by her. Instead of heading back to his friend and the boarding house, he followed her right out of the village.

They walked along the road from Balata, a path that twisted and turned with the barks of the trees. Iguanas were lazing across the branches and manicous sniffed the grass with their long snouts. No other living person was around. They were completely alone. She marched on and kept a steady pace, without looking back. Kabenla struggled to keep up with her.

Sweat dripped from his brow and his white shirt clung to his chest. He was used to this moist heat but it seemed as if they had been walking for hours. He tried again to spark up conversation.

‘Kijan ou rele? What is your name?’

‘