7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Universe

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Dark haired, slight, with deep-set haunted eyes, Herschel Grynszpan is an undocumented Jewish alien living in Paris. He receives a postcard from his parents – recently bundled from their Hanover flat, put on a train and dumped, with 12,000 others on the Polish border. Enraged, Herschel buys a gun and kills a minor German official in the German Embassy. The repercussions trigger Kristalnacht, the nationwide pogrom against the Jews in Germany and Austria, a calamity which some have called the opening act of the Holocaust. Intertwined is the parallel life of the German boxer, Max Schmeling, who as a result of his victory over the then 'invincible' Joe Louis in 1936 became the poster boy of the Nazis. He and his movie-star wife, Anny Ondra, were feted by the regime – tea with Hitler, a passage on the airship Hindenburg – until his brutal two-minute beating in the rematch with Louis less than two years later. His story reaches a climax during Kristalnacht, where the champion performs an act of quiet heroism.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

3

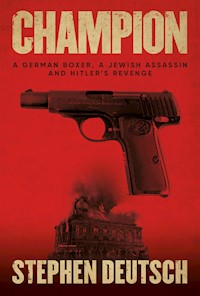

CHAMPION

A GERMAN BOXER, A JEWISH ASSASSIN AND HITLER’S REVENGE

STEPHEN DEUTSCH

5

For A, A and A

CONTENTS

PART ONE

CHAPTER 1

GLASS

9.11.1938

Picture this. Two SA men in tan uniforms, wearing swastika armbands, black riding boots and matching holsters, their faces glowing with artificial warmth, drops of perspiration on their unwrinkled brows. They stand, thumbs in their belts, fixated on the scene before them – pleased with what they see. One of them wears round eyeglasses which reflect the flames raging through the synagogue in front of him. The two men stand in awe of the ferocity of the fire. They have been tasked with ‘protecting’ the synagogue from the organised mob; members of their own SA unit, dressed in mufti, who had earlier ransacked the ornate eighteenth-century building. Laughing, shouting, throwing Torah scrolls onto the pavement, setting them ablaze – smells a bit like roast lamb, don’t you think? – or smearing pig shit on them.

Everywhere, the sound of fire-fractured roof beams crashing, explosions of glass, some of it showering onto the street below. The Berlin fire department hoses down adjacent buildings, but does not direct water at the fire itself, which is now spurting ferociously from every window and doorway. Aside from the hiss and growl of 9the conflagration and the shouts between firemen, there isn’t much noise. Sometimes a fireman’s boot crunches broken glass. Onlookers stare and marvel. Some smile.

SA-man Jürgen Meißner turns to his companion. He tells him an old joke.

‘An old Jewish tailor told me this. For a Jew, he’s a decent enough fellow…’

‘No such thing,’ his companion interjects mechanically, not averting his eyes from the blaze.

‘Well, this was before. And he is a good enough tailor. Anyway, this old Jew tells me this story. It seems that some other old Jew is crossing the street and is hit by a car. The driver gets out, is very sorry and tries to comfort the man, who is groaning on the pavement. He puts a folded-up blanket from the back seat under the man’s head. The victim then opens his eyes and gives a small smile of thanks. The driver asks him, “Are you comfortable?” The old Jew shrugs, “I don’t know about comfortable, but I make a living.” Jews are good at jokes, I think.’

Jürgen’s companion doesn’t share in the laughter.

‘That miserable little Jew-swine spoke the truth, at least. For them, it’s all about money.’

Jürgen nods, continuing to stare at the burning synagogue.

Kristalnacht had begun.

Max was alone, sipping a beer at the counter of the Roxy Bar, known by some as ‘the missing persons’ bureau’. If someone were late coming home, their wife would ring 10the Roxy before contacting the police. Six years ago, before Hitler, almost all of Berlin’s artists, actors, dancers, writers, movie directors and musicians could be found there, perched on stools or lounging within incongruous easy chairs, arguing, laughing, drinking and flirting into the late hours. By now most had disappeared; into exile – to the United States, France, England, even Hungary. Jews mostly, a communist or two. Definitely quieter now – a missing persons’ bureau of a different, darker hue. New faces, with Aryan features and uncontroversial notions had begun to appear, but most of the clientele hadn’t yet lurched with the country to the Nazis, or if they had, managed to cover their party badges before arriving. Anyway, at the Roxy people rarely discussed politics. ‘It makes too much stress. Better to gossip.’

This evening was an exception. The conversation had been about Ernst vom Rath, whose death a few hours before was in all the late editions. This harmless looking man, a nondescript bureaucrat in the Paris embassy, had been shot by a seventeen-year-old Jewish boy.

The Roxy’s owner, Willi Bauer, was absently drying a beer glass. He leaned across the bar towards Max. ‘But why would anyone, especially a Jew, do such a thing, Schmeling? For what purpose? It only can bring out worse.’

Max shrugged. ‘At that age people sometimes do crazy things.’

The telephone rang.

‘It’s for you, Max’.

‘Who can it be this late?’ 11

‘He didn’t say, but that it’s urgent.’

It was David Lewin, Max’s tailor.

‘Hallo, Lewin. Are you alright?’

‘Yes, Max, so far we’re fine, but I can tell you, we are very worried. Especially the boys. They’re really frightened.’

‘I’ve been hearing about it. Bad business. Listen, why don’t you send them to me at the Excelsior. They can stay in my suite for a while. I’ll be there in twenty minutes. Use the back streets. They’ll be OK.’

‘Won’t this make trouble for you?’

‘Let me worry about that, Lewin.’

‘Maybe I should send them in a taxi?’

‘It’s not that far, and you’ll never find one at this time of night. Just tell the boys to stay on the back streets and put caps on to cover their hair. They’ll be fine.’

CHAPTER 2

TURNING BACK THE CLOCK

The boy was trying to enjoy a small glass of kosher wine. ‘You only get to have one Bar-Mitzvah, son,’ his father said, ‘so you can live a little. But only a little.’ No one thought to laugh.

He stroked the blue velvet bag. On it a silver hand-stitched star of David, inside a new prayer shawl, yarmulke, and prayer book, as well as leather tefillin in its own smaller velvet bag. The house smelled of cakes, flowers and furniture polish, and there were newly fluffed cushions on the chairs.

He could smell rosewater when his mother leaned over to kiss him. She was wearing her new blue frock; a family present for her last birthday.

‘Use these every single day without fail, Herschel, his mother said, ‘and thank God for your loving family, and especially for your wonderful father who made this for you.’

He put on the shawl, his father straightening it at the back. He then tried the black silk yarmulke.

‘It keeps slipping off. Why won’t this stay on?’

‘That’s because your hair is too long,’ his sister Esther smirked. 13

‘You are beginning to look like a girl with all that hair,’ his brother Mordechai added.

He stuck out his tongue in response. ‘Maybe I can borrow a hairpin, Momme, to keep it on.’

‘Even better, Herschel,’ Mordechai laughed, ‘take some lipstick too.’

He made a move towards Mordechai, but was restrained by his mother.

‘We don’t fight in this house,’ she admonished.

The moment subsided. ‘I’ll love showing off the tallis and yarmulke in shul,’ he announced. ‘It’s the only place I feel at home, I feel safe. Except here, of course.’

Before Hitler came to power, the boy had idolised Max Schmeling and rejoiced when his German compatriot won the heavyweight championship of the entire world in 1930, although he won it on a disqualification.

‘He was beating Sharkey throughout, not so?’

They were standing with him in the corner of the schoolyard unofficially reserved for Jews. There was Wolf Weiss, who would delight his friends by bringing small cakes from his father’s bakery, Schmuel Rapaport, whose mother had been married once before to a man who died on the Somme, and Joseph Rosenstein, who was good with numbers. They formed a circle around the boy.

‘Everyone knew Schmeling was way ahead.’

No one argued with him – though small, his fists had a reputation of their own.

‘And that low blow that stopped the fight, Sharkey did 14this because he knew he couldn’t win.’ His peers nodded sagely.

‘And then after that, didn’t Max beat that Stripling, even knocking him out in the fifteenth round?’

‘Why did he wait so long to finish him? Answer me that, Herschel,’ asked Rosenstein, who was the tallest of the four.

Almost everyone was taller than he was.

‘He was just playing around with him, cat and mouse, to show who is boss. That’s how a proper champion behaves. Everyone knows that, even you, Rosenstein.’

When Schmeling faced Sharkey again in 1932 and lost on points, he shared in the general German outrage.

‘How could they give it to that loser Sharkey??! Our Max was miles ahead. No contest. It’s those biased American judges who cheated us.’

But his brother wasn’t interested. ‘Boxing is for gentiles,’ he said.

After Hitler became Chancellor, the boundaries of the boy’s world began to close around him, as if on casters. The changes were gradual but relentless. The first official restrictions against Jews seemed inconsequential, perversely beneficial.

Zindel put things into perspective.

‘Is it not actually a blessing for you, Herschel, that Jews are now excluded from military service? This isn’t for you a disappointment, is it?’

As each new regulation slid gradually into place, his father continued to offer optimistic consolations. 15

‘For you, at least, it’s no misfortune that Jews are now prevented from sitting examinations in medicine or dentistry. You hate the sight of blood, not to mention that your mother and I have to keep reminding you to brush your teeth, and when was the last time you passed an examination?’

Home was the boy’s refuge; he was fearful of leaving the house alone, even of walking to school. He tried to stay alert when outdoors, avoiding any groups of young men in the street, hiding from the government lorries which ambled noisily, loudspeakers blaring. Anyone who doesn’t belong in our country, leave! And soon! If you don’t, we’ll make it bad for you.

His thoughts screamed: but I was born here, idiots! But he kept shtumm.

‘It’s so unfair! I have to watch myself every minute when I go outside. Even at school. They all look at me. Always. As if I’m some sort of monster, or some sort of… I don’t even know what. I can feel people’s eyes following me. It’s all so unfair!’

‘But what can we do?’ his father asked. ‘We can’t push back the clock, Herschel. Who knows, perhaps things will change back again. Maybe people will soon see what that man is and kick him out. We must trust in God, Herschel.’

‘But why doesn’t God listen?’

‘We should leave Germany for good, Zindel,’ his mother said. ‘We should all go to Palestine.’

The children agreed.

‘Rivka, you know how hard it is to get in. The British have locked all the doors.’ 16

‘We should keep trying,’ she said.

When the family’s welfare payments, meagre as they were, stopped abruptly, Zindel could offer no consolations.

‘But without a letter, without a warning, just stopped,’ Rivka said.

‘Pointless to enquire,’ Zindel said. No one argued.

The Grynszpans instantly became much poorer.

Over time, new thoughts continued to jab at the boy’s mind, photographs in the newspapers showing his champion at one of those Party Day celebrations. Why is Schmeling so friendly with those Nazi bigwigs? How can he let himself be a Hitler pin-up? Is Max a Jew-hater too?

His support of the German champion waned quickly; his pugilistic allegiance soon shifted to the Californian, Max Baer.

‘This other Max, this better Max, a breath of fresh air,’ he proclaimed to his mother. ‘He’s an antidote, that’s what he is, an antidote. With his curly hair, and always smiling, and very witty, and what a suave boxer! And he’s a Jew! He even wears a large white star-of-David on his boxing shorts!’

But Rivka wasn’t so sure. ‘He’s not even properly Jewish, Herschel. Not by his mother, only by his father. And maybe not even by him. Who can say with gentile women, who they go with? But I agree, it’s nice of him to remember Jews on his boxing trunks.’

CHAPTER 3

CAN YOU SHOOT A GUN?

‘What are we going to do with you, Herschel?’ Zindel asked, during the short walk to the school. The boy didn’t reply. It was a mild spring day, a gentle breeze promising warmth, extravagant birdsong filling the air. But as they walked down the Burgstrasße, the Grynszpans were enveloped in wintry thoughts, as if the spring blessings were denied to them alone.

‘When your mother and I tell you something, you ignore us, just standing there like a statue, biting your nails, looking who knows where.’

He didn’t respond.

‘I know it’s been hard for you, Herschel. This is natural at your age, but you must make a special effort, particularly now, with all this craziness going on. An effort at home, an effort at school…’

‘I’m not staying on at school. I told you before. The others treat me like dirt, they stare at me, they pick on me. I fight back, but always get blamed for everything.’

Dr Berger rose as they entered his office. He offered his fleshy hand to Zindel and Rivka, then pointed to the 18three chairs in front of his desk. All sat, the boy in the centre. On the wall behind the Principal, the ubiquitous portrait of Hitler. Three-quarter view. Unsmiling.

However, Dr Berger did smile.

‘So, Herschel, young man, today a decision, yes?’

‘I have decided, Herr Principal, that I want to leave school now, as I am of the legal age to do this. You know that I have not been happy here. I have been picked on, just for being a Jew, and this has affected everything.’

Dr Berger opened a yellow folder.

‘Truthfully, Herschel, I think we can say that you were never a good student, even before. Hardly ever doing your homework, arguing all the time, getting into fights. But here it also shows that your grades have actually improved a bit since 1933, which given what you say, is surprising. And since repeating the sixth grade, you have shown some slow progress. But this is not surprising, as you are quite intelligent, a trait shared by many Jews, as my long experience can attest to.’

He smiled knowingly at the Grynszpans.

‘I understand what you say about bullying. I must admit that it occurs. Regrettable. I try to stamp it out. But one can’t be everywhere. It is of course natural that students from your folk community tend to band together, as in fact they have some reason to feel apart from the others, since this is a German school, and you are not German.’

‘I was born German.’

‘Well, it may be true that you were born in Germany, but the definition of German-ness is more complicated, as we now know.’ 19

‘At least the Jews don’t pick on me.’

‘But the teachers, they have all been considerate?’

‘Mostly. Except for that Frau Rausch, who last week made me stand up in front of the whole class, next to that giant imbecile Wolf Martins, so that she could show the differences between a Jew and an Aryan.’

He looked to his silent parents for some sign of support, or even mild outrage, but each stared down, as if they too were being chastised. Dr Berger closed the file.

‘This is all of little importance now, I think, given your decision. I understand that the government is soon planning to restrict German schools only to Germans, so perhaps you have decided to leave at the right time.’

Dr Berger smiled warmly and rose. ‘Let me take this opportunity to wish you and your family all good wishes for the future.’ The three Grynszpans went home.

‘This is not a good situation for you, Herschel. You have no diploma, your Principal’s report says that you are ‘mean-spirited, sullen, taciturn, sly…’

‘They hate all Jews. What can you expect? Do you believe that Nazi?’

‘Maybe you forget that you were even kicked out of the Jewish Day Centre. They asked for you to leave, again for arguing, for fighting. Your mother and I pleaded with them, so they let you stay, but only a few weeks later you were expelled. Because if you came up with any crazy idea, you’d tell everyone, and then if they disagreed, you’d punch them. Even at home I’ve seen this anger in you. 20The veins in your forehead and neck sometimes stand out with rage. Over little things, trifles.

‘So what now to do? No diploma, no skills, you remain argumentative, sullen. In such a situation as this, what are you good for?’

He stood there biting his fingernails until his mother pushed his hand away.

‘Maybe I can be a fighter for Jews. At the Maccabee Sports Club, some of my friends are now applying to emigrate to Palestine. They say that even the Nazis will help them. So maybe that. Maybe the whole family can go.’

‘But you left the Maccabees.’

‘They wanted everything to be so military! Everything organised. Just like the Hitler Youth.’

‘And you’d know all about the Hitler Youth, yes?’ Rivka asked.

The boy glowered.

The following week, the boy and his parents, dressed in their finest High Holiday clothes, arrived at the offices of Hanotea Ltd.

‘Let me straighten your tie,’ his mother said, pushing his hands away. ‘First impressions are very important.’

He scowled. ‘In photographs from Palestine no one wears ties. I should take it off. That will make an even better impression.’

‘In Germany, we still wear ties,’ his father said, ending the discussion. 21

They climbed the stairs, opened the glass panelled door. They were greeted by a stout, middle-aged man, sitting behind a small desk. Behind him stood acres of shelves, rising to the high ceiling, filled with box-files. Noisy traffic could be heard through the window. A small portrait of Theodore Herzl, the founder of Zionism, was fixed to the wall behind. On the desk, two smaller signed photographs, in silver frames, of Haim Weizmann and David Ben-Gurion, current leaders of the Zionist movement.

‘Levy,’ the man announced. He stared at them. ‘You are?’

Zindel introduced himself and his family in Yiddish.

‘Let me stop you there, Grynszpan,’ Levy said, holding out his arm like a traffic policeman. ‘In Palestine, in the Land of Israel, we do not speak Yiddish. Understand? It is the language of the shtetl, a bastardised amalgam of Hebrew and German. In Palestine we are building a new land out of the barren dust and ashes of the old, and so you will understand that Yiddish has no place. We need a new kind of Jew as well; therefore only Hebrew. But as I see from your faces that you don’t speak the language, today we can do our business in German. I assume you are here about emigrating.’

The Grynszpans nodded in synchrony.

‘I am a Jew and I want to help build Palestine.’

‘Good lad,’ Levy said, while writing their names in the large book. He then looked benevolently in their direction. He leaned back in his padded armchair.

‘The official name of this company is Hanotea, which 22means ‘the planters’. It is actually a citrus fruit company now importing German agricultural goods into Palestine. But it is also aligned with the Jewish Agency, which is where I come into the picture.’

His visitors nodded politely.

‘Emigrating is definitely a good idea, especially now. So to the whole world’s surprise, we have managed to make a deal with both the Nazis and the British. The deal is called Ha’avarah. This is how it works. First, you put your money into a blocked account – it is frozen until you arrive in Palestine. Then, when you arrive, the Jewish Agency takes about a third of it, in order to help more people emigrate and settle. The German government also gets a third. The rest of the money you can keep, but only in the form of German goods which are sent to Palestine and bought by Hanotea, then sold on. You get the proceeds.’

Their silence surprised Levy.

‘So something is better than nothing, yes? And let me tell you, that when you get off the ship, probably they will first put you in a nice apartment in Tel-Aviv, maybe Haifa. Forget about a kibbutz – we don’t send German Jews there, mainly Americans. And then you’re safe, you’re finally free, and then you can start a new life.’

Zindel asked, ‘What about the British? I thought they were strict about anyone coming to Palestine.’

‘That’s the beauty part of the agreement. The funds are managed by the Anglo-Palestine Bank. It’s all completely kosher. Now, tell me, how much money can you put into the account? Once the money is deposited, the British Government will issue you an entry permit and the 23German Government will let you out. So tell me, how much money are we talking about? The normal amount is at least £1,000.’

The Grynszpans exhaled in unison.

Zindel said, ‘We could maybe find a tenth of that, with help from relatives, but we have very little money ourselves. And the government has even stopped our welfare payments. No reasons, just stopped.’

Levy closed his book.

The boy rose, his fists clenched. ‘But I want to fight for Jews. I want to fight the Arabs and the British anti-Semites. I can work, I can do whatever is required. Don’t you ever take Jews with no money?’

‘Rarely. We are not organised for such purposes. We’re a business. It is true that sometimes we help organise passage for orphan children, sometimes young people with exceptional skills, but it’s difficult. Do you speak Hebrew?’

‘I have attended Hebrew school in the afternoons, and regularly go to the synagogue, three times on the Sabbath!’

‘That doesn’t count. Synagogue Hebrew is not the modern, living Hebrew, no comparison. Can you shoot a gun?’

‘I’ve never tried.’

‘Well, it might have been possible if you had some useful practical skills, or some kind of agrarian training, but as it stands…’

‘I was a member of the Maccabees, but I left…’

Zindel and Rivka had already risen. ‘Thank you for your time, Herr Levy,’ Zindel said. 24

‘Don’t mention it.’

The Grynszpans closed the door quietly as they descended into the bright spring day.

CHAPTER 4

WATCHING A FILM

They were sitting on a green leather sofa, staring at a screen. June sunlight was held in check by heavy red curtains, through which only a single brilliant shaft sliced into the room. Blue-grey smoke danced upwards, illuminated by the projector. Joe Jacobs puffed on his cigar. People usually called this little man Yussel – Yussel the Muscle.

The film finished, clackering on its spool. Yussel leant forward, turned off the projector and stared at the much larger man sitting next to him.

‘You see that, Max?’

‘I see what I saw at ringside. He punches harder than anyone I ever saw before, maybe even harder than Dempsey.’

‘Yes. Goes without saying. Louis really gave that big wop lunk Carnera a shellacking. But he still has a lot to learn, and you can teach him, Max. They all think you’re a bum, Max, winning the championship on a foul, then losing it on points by not finishing Sharkey off. You were miles ahead on points, of course, but they stole it, the bastards.’

Max grinned. ‘You were a picture, Joe. Running around the ring, waving your arms like a windmill, shouting, 26“We wuz robbed! We wuz robbed!” over and over.’

‘I shouted till I was blue in the gills, but of course they wouldn’t listen. Now they think you’re washed up. They’re underestimating you, Max, so that’s good for us.’

Yussel re-spooled the film and switched the projector back on. They stared again at the black-and-white images, ignoring the projector’s noise; the silent scene of a bleached-out ring, where two men, one black, the other scared, circled each other jerkily.

‘Do you see now, Max?’ Joe bit heavily on his sodden cigar.

‘You mean after the jab?’

‘Now you got it! He drops his left after every jab. He’s just asking for a right cross.’ Yussel mimicked the moves.

‘Maybe someone else thought of that before.’

‘Well if they did, they didn’t last long enough to try it out. He’s just too fast for them. And anyway, they were mostly kids, or clowns, or has-beens, or no-hopers. Bums with glass jaws.’

‘But Louis can take a punch. Do you really think I can beat him, Joe?’

‘Certainly, or I wouldn’t be sitting here looking at this cockamamie silent movie on such a nice day. Listen’, he took another long pull at his stogie, ‘Louis makes amateurish mistakes which he can’t afford to make against you. But he’ll keep making them anyway, since everyone is telling him he’s so great and that no one can beat him.’

‘So if I just keep moving to my left and wait for the arm to fall, I can get him?’

‘It’s simple ring intelligence. That’s the most important 27thing, a good right and an even better brain. Just keep into your crouch and make him reach out for you, make him find you, then spring up with your big right. That’s all you need. We’ll train for that. Anyway, the crowd will be right behind you, even in New York. They’re only hoping that some white man will knock the bejesus out of that schwartzer. They still haven’t forgotten Jack Johnson, and how he spoiled things for all their white hopefuls, and how he ran around with white women, and teased all them palookas in the ring before flattening them. OK, Louis is more polite, but he’s still a nigger, isn’t he? So they’ll be behind you even though you’re a German, because they’re desperate for Louis to lose. Of course, in Harlem people will root for their own, but only on the radio, since they can’t afford to come to Yankee Stadium, can they?’

‘Joe Louis is a good fighter, though.’

‘Not a good fighter, Max, a great fighter. Strong and young. Smooth and fast. But inexperienced. And maybe a little bit stupid. That will change, but not yet. The main thing is, he’s black. And you’re not. Let’s look at the film again.’

CHAPTER 5

THE YESHIVA

‘Let us look at the facts,’ Zindel said. ‘The facts are as follows. You have no qualifications. You have no job. Or any prospect of one. Your thoughtful brother Mordechai has already asked his employer if you could come and join him as a plumber’s apprentice, even though he already knew what the answer would be. “One Jew, even a decent one like you, is enough, I think.” That’s what Herr Dollman told him. And now Mordechai is worrying about his own job.

‘More facts. We don’t have enough money. The welfare is gone. My few tailoring jobs are flowing away like rainwater in the gutter. So you’ll need to find something to do to help us. But what?’

‘I’ve been thinking about this, Poppe. I’ve been thinking about what I could do to help the family, to help us emigrate to Palestine. But how? Especially after our meeting at Hanotea. So, I’ve been thinking that perhaps they don’t only need muscles in Palestine, but maybe they need rabbis, too. After all, with all those Jews living together, in a new place. And also, you know that I have always been very observant. I go to shul every day, I celebrate all the holidays and observances, and I think I could be a good 29rabbi. So maybe I could train to be a rabbi and emigrate that way. Afterwards the whole family can come.’

‘You mean to go to a Yeshiva?’

‘I guess so, if some way could be found to send me.’

Zindel and Rivka regarded him silently. Then Rivka rose and walked to the kitchen. ‘Tea is good when decisions need to be made.’

‘Better schnapps,’ Zindel said.

‘We can’t afford it, and anyway, he has enough time to be a drunkard on his own. We don’t need to help him.’

Zindel turned to his son, offered him a half-smile. ‘This might not be such a stupid idea. In any event, it would keep you somewhere more-or-less secure instead of roaming the streets of Hanover, so easy for them to pick you up and send you who knows where. But this also involves expense, this Yeshiva.’

Rivka returned with three glasses of lemon tea, but without any lemon. ‘Lemons are too expensive nowadays,’ she announced, as if this were news.

The boy became more animated. ‘I was talking to Michael Solomons the other day. You know him. His father was the other kosher butcher, the one on the Johanstraße, the one that was just closed down. He said that the Jewish Community Centre is willing to support someone who wants to go to a Yeshiva. And they’d pay. And there’s a particular Yeshiva in Frankfurt, not the big famous one, but a small one in the old ghetto, that might be a good place. And I could live and study there, and you wouldn’t have to give me any money.’

‘They would do that? Even with things as they are?’ 30

‘Absolutely,’ he guessed.

He sent letters.

He almost tore the letter in his haste to open the envelope.

‘They’ve accepted me! Momme, Poppe, they write that I can come right after Rosh Hashanah. And last week, the JCC said that if I was accepted, they would send 15RM a month for support.’

‘We must prepare for this,’ Rivka said. ‘Zindel, maybe make him a new suit? He’ll need a new coat too, by the way.’

They took an early train to Frankfurt, and the brisk morning walk from the station to Ostendstraße filled him with wonder. It’s so big! So many theatres, cinemas and cafes! As usual, most had signs stating: ‘Jews are unwelcome here’. The same Nazi flags and banners, and the same SA thugs walking in pairs.

‘Remember, Herschel, as we walk, never look anyone in the face, and get into the gutter if any SA or police come along. And move quickly, like you’re going somewhere official.’

‘I know this, father. It’s the same at home.’

‘It doesn’t hurt to remind ourselves.’

It was an old building in an even older street. They were greeted at the door by Rabbi Lippmann Rachow, the headmaster.

He looks so old, with a genuine rabbi beard. A kindly face, though, through all those whiskers. 31

Reb Rachow smiled warmly at them, took the boy’s small suitcase and ushered them into his office.

It was a small, austere space. Four straight-backed chairs and an old wooden table, piled with papers and open books, filled most of the room. All available wall space was covered with shelves, on which heavy volumes groaned, their spines written in Hebrew, in German, a few in Russian.

Reb Rachow spoke to the Grynszpans in Yiddish.

Not like that fat Levy at Hanoteah, the boy thought.

‘It’s wonderful that you have brought to us your son to begin his studies,’ he said. ‘Nowadays, not so many young people are interested, and as a result, we don’t have that many scholars with us. Still, we have just enough.’ He looked at the boy and smiled with his eyes.

‘Herschel, I tell this to all the boys, so why not you, eh? The word “Yeshiva” comes from the root of the Hebrew verb lashevet, which means “to sit”, sitzen. And sitting in the classroom, or at your desk in the dormitory, studying the wonderful holy books, that is what you will do most of the time. And you will enjoy it so much, that you won’t even notice the time going by! But to do this you will need to develop the bottom-flesh, sitzfleisch, so that you can concentrate all your attention on your learning. It goes without saying that we also have other activities; young men need to get exercise, to stretch out and smell the air.’

Rachow paused to gauge his response. The boy smiled.

‘Let me show you the classroom and your dormitory.’

The Rabbi led them down a musty corridor to the 32classroom, a teaching space which doubled as a small synagogue.

‘You’ll sit here.’ He pointed to a place on one of the wooden benches set up as school-desks, in three rows, facing the ark where Torah was kept.

Maybe there are cushions, the boy wondered.

‘This is where you will develop your sitzfleisch. After a year or so, you will sometimes sit in another room, around a large table, where you young scholars can discuss the things you have learned, especially the book of laws, the Mishna, and the fascinating commentaries that great scholars have made upon those laws. This is called the Gemara.’

I know about these things already, so I can make a good start.

The three then walked over to the dormitory, once a capacious room, now cramped. It smelled of old shoes, books and tears. He first noticed the four triple bunks, constructed of rough wood on which rested horse-hair mattresses covered with striped sheets. There were four wardrobes and four sets of drawers, constructed from the same wood as the bunks. Along the length of the far wall, a long table, over which shelves of books loomed. A small black stove on a flagstone plinth occupied the centre of the room. Four small windows threw sunless light onto the floor.

‘Soon, the other boys will come and show you around, and they will make space for your clothes in the wardrobes.’

Zindel left soon afterwards, satisfied about the accommodation, and pleased by the Rabbi’s affable gravitas. He looked forward to telling Rivka, Mordechai and Esther all about the place, about the relief of speaking 33Yiddish, and how at home Herschel seemed, even on his first day. He was just able to catch the early afternoon train back to Hanover.

Alone in the dormitory, he sat on a bottom bunk, his suitcase at his feet, as if he were waiting for a train. For the first time in months, he felt optimistic.

Such a relief. I’m sure I will fit in here. Maybe even make some friends. And I’m really looking forward to my studies. Who knows, in five years, I might become a rabbi! And then we can all go to Palestine.

His first visit home was to be a joyous occasion. The family had been planning it for days.

‘But why, Rivka, do we have to get our meat at Mendel’s? So expensive.’

‘Because there’s nowhere else. I told you before. They closed down Solomon’s shop. And when I asked Mendel why his meat is so expensive, do you know what he said?’ She tried to imitate butcher Mendel’s sing-song voice. Do you think, Mrs Grynszpan, that it’s easy to get kosher meat nowadays? Now that kosher slaughtering is banned in Germany? And by the time I get the meat from Denmark, and it meets the approval of the rabbis, for how long do you think it keeps? If only people bought more kosher meat, the price would go down, but so many are now eating mostly fish, even God forbid, vegetables.’

Zindel relaxed. ‘Well, I suppose for such a special occasion, a bit of flanken is not such an extravagance. So long as there’s plenty of potatoes and vegetables.’ 34

‘Thank God,’ Rivka said, ‘the outdoor vegetable market is still Jew-blind.

From the soup course onwards, the boy couldn’t stop talking, his napkin tucked into his shirt-front.

‘I didn’t think I’d like it at first, but getting up early and praying three times every day I now find very satisfying. The regularity of it all, the daily study in the morning and afternoons, all this routine calms me.

‘And I’ve definitely learned something about sitting, that’s for certain. But it’s easy because the studies are wonderful. You know how I love the Torah, all those stories about Abraham, Moses, Joshua, Kings Saul, David and Solomon, back in the days when the Israelites were heroes and warriors. We have also started on the Mishna, the book of laws derived from the Torah.’

Mordechai looked across at his younger brother. ‘We all know what the Mishna is, little pischer. You’re telling us something new?’

He ignored Mordechai. ‘The Mishna is now my favourite study. In it, an observant Jew can find all he needs to know about everything. Everything has a law; everything has a place. Eating, working, property, marrying – everything is covered. With these laws, we are no longer rudderless, and when we have our own land, we can put them into practice!’

‘This may take some time, Herschel,’ his father said.

‘I asked Reb Rachow how can we fight against what the Nazis are doing to us. He answered, “We must have 35faith, Herschel. And we must be patient. He alone has the power to save us. As He has done before, in the Sinai, by parting the sea, and giving us manna for food, and when He acted through Esther against the murderous Haman. He will save us again.” I told him, I’m young, I can wait. And when I am a rabbi in Palestine, I can help build a home for our people.’

His next visit was at Chanukah.

As the meal began, his sister, Esther, asked, ‘So, Herschel, how are the studies going? Have you developed more sitzfleisch? Turn around and let me see.’

Mordechai tittered.

He ignored them. ‘I am still enjoying my studies and have even made a few friends. Minshkin is my best friend; he shares my desk. He’s from Berlin, by the way. We sometimes go out for walks together – don’t worry, we are very careful – and even sometimes we have some tea in the Jewish Café not far from the Yeshiva.’ He looked down at his plate, a solitary dumpling floating amongst thin noodles and a lone carrot in a pale-yellow liquid.

‘But, I have to admit that I’m having trouble with the Gemara, the books of commentaries on the laws. In the Mishna everything is clear, the laws are straightforward, and everyone knows how he should behave in order to be a good Jew. But the Gemara, that’s another matter. There are too many different opinions. We read that Rabbi Elazar says one thing, Rabbi Yehoshua says another, and Rabbi Gamaliel another thing entirely. For example, we 36spent four entire days discussing what should happen if a farmer’s bull strays into a neighbouring field and gores a pregnant cow to death. Does the farmer pay damages just for the cow, or for both the cow and the calf? For four whole days we discussed this, reading all the opinions from those old scholars, who all lived in Babylon hundreds of years ago. And at the end I was no wiser. I got into trouble for suggesting that maybe the story was there to tell us to build better fences. So I don’t really know what to think.’

But what were you expecting, Herschel?’ his father asked. ‘It’s a Yeshiva. In a Yeshiva you study such things.’

‘I know, but I thought that they would be also teaching me all about how to be a good rabbi, how to help other Jews out with their problems. Not to be a lawyer. But maybe I’ll see the point of the Gemara later.’

He came home again in April, in time for Passover. He had always loved this festival, especially the Seder meals, the glasses of wine, the reading of the story of the Israelites escape from Egypt, not to mention the food, now somewhat less copious than in previous years – all this followed by wonderful songs. However, on this visit he was more subdued. He took part in the ritual, but went to bed immediately after the Seder. The next day, he handed his parents a letter from Reb Rachow. 37

My Dear Mr and Mrs Grynszpan