5,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: The Lilliput Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

This 'new journalism' by Irish Times women writers originally appeared on the Women First pages during the 1970s. Together, the pieces reflect the enormous social and political upheaval of the years when, as the first woman's page editor Mary Maher put it, "Irish women were invented". The voices of this exciting anthology, diverse, sparkling, irreverent, record with wit and intelligence an Ireland on the brink of transformation. Changing The Times showcases the best of this writing, by Maeve Binchy, Mary Leland, Gabrielle Williams, Christina Murphy, Geraldine Kennedy, Maev Kennedy, Eileen O'Brien, Caroline Walsh, Theodora FitzGibbon, Nell McCafferty, Renagh Holohan, Elgy Gillespie and others. Issues of the day are articulated and explored: pregnancy, fashion, first loves, sexuality, a burgeoning feminism, an imploding Catholic Church, an exploding North. Nell McCafferty profiles a young Ian Paisley, visits New York and talks to the family of a girl tarred and feathered in Derry; Maeve Binchy interviews Samuel Beckett and Iris Murdoch; Mary Holland follows the North, while Renagh Holohan is caught in its explosions; Elgy Gillespie encounters Muhammed Ali, Tyrone Guthrie and Robert Lowell; while Mary Cummins interviews Bernadette Devlin about having her first baby. As the mirror of a confident young nation, and a window onto one of the most eventful decades in recent Irish history, Changing the Times gives these writings the afterlife they richly deserve.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Preface

Introduction MARY MAHER – ComingofAgewithaVengeance

Chapter 1 – First Times

INTRODUCTION

MAEVE BINCHY – BabyBlue:MyFirstBestDress

NELL MCCAFFERTY – FirstDance

MARY CUMMINS – AllOurEasterdays:NewDresses,Picnics,andaRetreat

MARY LELAND – TwoMarysGototheDance

CHRISTINA MURPHY – FirstLove:TeenageIdol

MAEV KENNEDY – AllWrite:PortraitoftheArtistasaSufferingDaughter

ELGY GILLESPIE – WomenSeekRealQuality

Profiles

NELL MCCAFFERTY – ADayISpentwithPaisley

MARY LELAND – ReturntoBowen’sCourt

ELGY GILLESPIE – FirstInk:VisitingTonyGuthrie

Chapter 2 – End of an Era

INTRODUCTION

MARY MAHER – How’stheMs?

NELL MCCAFFERTY – MyMother’sMoney

MARY MAHER – NightoftheKillerCabbage

THEODORA FITZGIBBON – LiberationIsaStateofMind

MAEVE BINCHY – OurComplimentstotheCook

MARY MAHER – HowMuchMothering?NoelBrowne’sView

MARY CUMMINS – ANurseattheRotunda

MARY MAHER – BabyFactories

GABRIELLE WILLIAMS – What’sinaBag?

NELL MCCAFFERTY – AllOurYesterdays:CoatTales

GABRIELLE WILLIAMS – TheTimelessLittleBlackDress

NELL MCCAFFERTY – WhatWilltheWell-DressedManWearduring1974?

Profiles

ELGY GILLESPIE – MuhammadAli

MARY LELAND – DrLucey: ARockagainstChange

EILEEN O’BRIEN – MosleyForeseesaUnitedIrelandwithintheEuropeanCommunity

Chapter 3 – Out and Proud

INTRODUCTION

MARY CUMMINS – TheChristmasRush:OnceMorewithFeeling

ELGY GILLESPIE – OntheRoadAgain

NELL MCCAFFERTY – Mugged,Raped,andKilled

GERALDINE KENNEDY – FirstEncounterwithaLeper

ELGY GILLESPIE – MidnightCowgirl:NewYorkona J-1Visa

Profiles

CAROLINE WALSH – SeamusHeaney:“Asituationbothgrossanddelicate…”

ELGY GILLESPIE – RobertLowellinKilkenny

Chapter 4 – Our Bodies, Ourselves

INTRODUCTION

MARY LELAND – FatherMarxandAbortion

MARY MAHER – SurveyingtheMarriedWoman

CHRISTINA MURPHY – BachelorGirlorSourSpinster?

CHRISTINA MURPHY – TheContraceptiveDebate:EndingorBeginning?

ROSINE AUBERTING & CHRISTINA MURPHY – TheFortyFootCampaign:TwoViews

MARY LELAND – InDefenceofEroticism

ELGY GILLESPIE – WillUnmarriedFathersPleaseStandUp?

MARY CUMMINS – SuitableforMotherhood?

CHRISTINA MURPHY – MySo-Called“Condition”

Profiles

CAROLINE WALSH – TheCriticsandEdnaO’Brien:Envy,Envy,Envy

CHRISTINA MURPHY – Here’sToYou!SenatorRobinson

MAEVE BINCHY – ShyMissMurdochFacestheBallyHoo

Chapter 5 – The North Erupts

INTRODUCTION

MARY CUMMINS – BernadetteDevlinExpectingBabyinAutumn

ELGY GILLESPIE – NoSurrender:SoFar,SoTribal

ANON. – SecondGirlEngagedtoSoldierIsTarredinBogside

NELL MCCAFFERTY – We’reAllTerroristsNow:“JesusChristHimselfCouldn’tStickIt”

NELL MCCAFFERTY – ThreeMenDieonBarricade:TroopsConductDescribed

NELL MCCAFFERTY – DerryNumbedandRestlessinAftermathofKillings

MARY CUMMINS – VisitortoLongKesh

RENAGH HOLOHAN – ExplosionWrecksBelfastStation:NightoftheBigBangs

MARY HOLLAND – AcesthatWhitelawCanPlayinDirectRule

MARY HOLLAND – SecondThoughtsonSunningdale

ELGY GILLESPIE – GospelofTwoUnionJacksonHigh

Profiles

ROSE DOYLE – Gerry“Bloomsday“Davis:“I’llShowThem!”

RENAGH HOLOHAN – TheToughestNotOnlySurvivebutWin

MAEVE BINCHY – BeckettFinallyGetsDowntoWorkastheActorsTakeaBreak

Biographies

About the Author

Copyright

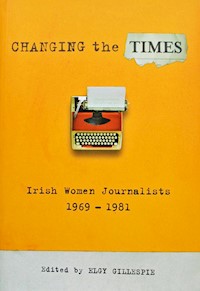

Women of the Irish Times (clockwise from above): Gabrielle Williams, Maeve Donelan (sub-editor), Mary Cummins, Caroline Walsh, Geraldine Kennedy, Mary Maher, Renagh Holohan, Christina Murphy.

Preface

How Irish Women Journalists Changed the Seventies

It all began with Douglas Gageby’s news editor. When the founder of the EveningPress moved from Burgh Quay to D’Olier Street early in the sixties, he hired Donal Foley, who had worked for the IrishTimes in London.

Donal was the son of a national schoolteacher in Ring and a native Irish speaker whose loyalty to his culture was matched by his determination to hire diversely, and that included women. To paraphrase Walt Whitman, he sang the Body Eclectic. Gageby had unleashed an unpredictable, intuitive and wholly original intelligence inside the newsroom that resulted in a feminist army of sorts. Yet it was a seemingly random process.

Foley was tolerant and open, interested in the North and in the Language as well as in women. He was interested in everywhere and everyone. Together, Gageby and Foley initiated changes that began with bylines, foreign coverage, investigative reports by Michael Viney, and bringing the ungrateful Northerners a Belfast edition—radical steps now taken for granted. But the most exciting change came in the form of the Women First page, and the women writers who filled it; led by Mary Maher and Maeve Binchy, they penned the ripping reads of the day—first-person entertainments exposing shame, scandal, fear, misery, and abuse. The New Journalism had arrived, and we put ourselves in every story.

Donal really enjoyed our company over those three-to-four hour lunches and drinks in the Harp, and on through those legendary evenings at the Pearl—as we also enjoyed his great explosive laugh and bonhomie, sometimes until it was time for us all to jam into the elderly Fleet Street elevator, swaying together towards the deadline din of galloping Facits as we sang “The Rose of Tralee”. Or totter home on the bus, still singing “The Rose of Tralee”.

We had our talented counterparts in the IrishPress and the Independent, most famously Mary Kenny, but we knew we had something that they envied and could never have: absolute press freedom with Douglas Gageby and Donal Foley’s support. Donal sometimes shook his head at our youthful idiocies, and he had no interest in the cooking or clothes columns that were expected of women’s pages back then.

We drove him crazy. We drove Gageby crazier. I segued to Arts where I drove Fergus Linehan and Brian Fallon crazy too—until the new editor Fergus Pyle invented a history series to spare them. Let’s face it, we drove the entire island crazy, especially Mrs Maureen Ahern of Corbally and the Dean of Killala who wrote to the Editor daily. On our gravestones let it be engraved: “We drove them all crazy, especially the ones in Corbally.”

Way back in kinder and gentler 1971, everybody had apparently landed there through meandering, Alice-in-Wonderland sequences, as though they’d fallen through a series of upside-down holes into that forgiving, warm, indescribably dusty Dickensian burrow, born backwards from the cruel world outside. Donal also hired men, in a fortuitous but logical way—Lionel Fleming, Denis Coghlan, John Armstrong, Joe Joyce, Andy Hamilton, Jack Fagan, Nigel Brown, Michael Heaney, Godfrey Fitzsimons: equally diverse. But to the consternation of the other editors in D’Olier Street, his women just seemed to wander in off the street.

How on earth did the IrishTimes find the high-hearted schoolteacher Maeve Binchy, the fine-featured Chicago-born idealist Mary Maher, the effortlessly organized and kind Renagh Holohan, the principled Gaelophile Eileen O’Brien, the bandbox-elegant and bright Gabrielle Williams, the epicurean Theodora FitzGibbon, the rhapsodic nurse from Ballybunion Mary Cummins, the fearless civil-rights activist Nell McCafferty, the tasty Leeside wordsmith Mary Leland, and later on myself, Christina Murphy, Geraldine Kennedy, Maev Kennedy, Ella Shanahan, Caroline Walsh, and more?

How had we all come to be hired by County Waterford’s gift to the Street of Shame, Donal Foley?

Or to rephrase the question: how did Irish women journalists come to change the seventies? To revisit seventies journo-speak, this book is looking for answers and means to find them.

Elgy Gillespie

31 July 2003

Introduction

Coming of Age with a Vengeance Mary Maher

It began, as so many things do, in a pub. On that particular day we were arguing about women journalists, women’s journalism, and whether or not a newspaper should have a “women’s page”. I was vehemently opposed. From the time when I ran for opera tickets and takeaway coffee for the society editor of a Chicago daily, I was conscious of the fact real reporters regarded the field with contempt.

My definition of a real reporter was unclear. At seventeen, I greatly favoured the crime reporter with the dangling cigarette. By twenty-two, when I was officially incarcerated on the society desk, bashing out wedding descriptions and correctly spelling the names of those who were there to be seen, he had been replaced in my esteem by the political correspondent, whose face was thrillingly cynical.

I was more certain than ever that my own colleagues who womanned the society, fashion and club desks of the almighty ChicagoTribune were without journalistic merit. Silly twits and dolly-birds, we gushed out a pastiche of florid adjectives, coy advice and moronic euphemisms on cooking, clothes, homes, housework, shopping and other dull subjects. I finally begged my way into the real newsroom to write solemnly about fires and police reports, and took for granted the fact that I’d learned to spell names correctly, to write under a deadline to the required length, to place facts in the first paragraph, and when in doubt to leave out: all precepts of the trade passed on by silly twits.

Were they all as bored with the limitations imposed on them as the readers must have been? Of course. Could they have done anything about it then? No. The women’s pages were designed by male editors with the advertising department, for housewives whom they imagined had only one interest: to buy things to bring home. Female readers who didn’t conform could always turn to the rest of the paper (the “men’s pages”). When Betty Friedan published TheFeminineMystique, with its painstaking and painful analysis of how women’s journalism had reinforced the kitchen and nursery subjugation of American women, I thought the final word had been said, and the only answer was abolition.

So four years later, on a rainy afternoon in Dublin, I found myself battling an illogical but rather attractive hypothetical question from Donal Foley. Why not a women’s page with serious articles, scathing social attacks and biting satire, and all that? Why not? Why not combine the real reporter bit with a concentrated focus on the wrongs suffered by women, plus useful factual information for the women whose work happened to be running a home? No point, I said, in creating a ghetto cut off from the real world of face powder, luncheons and marmalade recipes.

I became the women’s editor. Renagh Holohan and I, and a handful of contributors, had a whole half page to flail away with every day, and flail we frequently did. Mostly we tried to do more straightforward reporting on the traditional topics: inquiring into the market price of fish and its retail mark-up, and dourly pointing out fraud in the Annual Sales!

There were articles on censorship, slum property, the housing shortage, the class bias of education, exploitation of factory girls, corporal punishment, and a few initial attempts to raise the matter of equality along the order of “Women Drive Better than Men” and “When Will the Unions Fight for Equal Pay?” It was a beginning. Contraception, unmarried mothers, deserted wives, family law, children’s courts, prison conditions—all the issues that didn’t exist out loud in 1967—were to follow, faster than we perhaps imagined.

Eighteen months later I was exuberant with relief to turn the running over to Maeve Binchy and venture back into the newsroom. The best to be said about that initial period was that a somewhat different women’s page did get established. The other national dailies followed suit within months of the inauguration of Women First with their own pages. When the Women’s Liberation Movement burst upon us in 1969, Irish women’s pages became a forum. Whether what they’ve said has been totally worthwhile may be debated; but at least it was controversial, and that was a women’s page first.

So controversial were they that they have phased themselves out, like the fellow who kept the wheel turning until he’d worked himself out of a job. When the women’s pages came of age, they did it with a vengeance; and I think with satisfaction of how shaken up all those real reporters must have been. Served them right, the silly twits.

26 October 1974

Chapter 1

First Times

Introduction

What Irish girlhood meant in the old days, bad or good, and what it was like for a Dalkey teenager, a budding Derry activist, a Ballybunion schoolgirl, the nubile young women of Cork and Kerry, a Mayo convent girl, a Rathmines Edna O’B-to-be, a London-Irish student at Trinity College, an Irish-American cub reporter, and more.

Maeve Binchy

Baby Blue: My First Best Dress

My first evening dress was baby blue and it had a great panel of blue velvet down the front, because my cousin who actually owned the dress was six inches thinner everywhere than I was. It had two short puff sleeves, and a belt that it was decided I should not wear. It was made from some kind of taffeta, and it had in its original condition what was known as a good cut.

It was borrowed and altered in great haste, because a precocious classmate had decided to have a formal party. A formal party meant that the entire class turned up looking idiotic and she had to provide twenty-three idiotic men as well.

I was so excited when the blue evening dress arrived back from the dressmaker. It didn’t matter, we all agreed, that the baby blue inset was a totally different colour from the baby blue dress. It gave it contrast and eye-appeal, a kind next-door neighbour said, and we were delighted with it. I telephoned the mother of the cousin, and said it was going to be a great success. She was enormously gratified.

I got my hair permed on the day of the formal party, which now, many years later, I can agree was a mistake. It would have been wiser to have had the perm six months previously and to allow it to grow out. However, there is nothing like the Aborigine look to give you confidence if you were once a girl with straight hair, and my younger sister, who hadn’t recognized me when I came to the door, said that I looked forty, and that was good too. It would have been terrible to look sixteen, which is what we all were.

I had bought new underwear in case the taxi crashed on the way to the formal party and I ended up on the operating table; and I became very angry with another young sister who said I looked better in my blue knickers than I did in the dress. Cheap jealousy, I thought, and with all that puppy fat and navy school knickers, plus an awful school-belted tunic as her only covering, how could she be expected to have any judgment at all?

Against everyone’s advice I invested in a pair of diamanté earrings that cost one shilling and threepence in old money in Woolworth’s. They had an inset of baby blue also, and I though this was the last word in co-ordination. I wore them for three days before the event, and ignored the fact that great ulcerous sores were forming on my ear lobes. Practice, I thought, would solve that.

The formal party started at 9 p.m. I was ready at six and looked so beautiful that I thought it would be unfair to the rest of the girls. How could they compete?

The riot of baby blue had descended to the shoes as well, and in those days shoe dyeing wasn’t all it is now. By 7 p.m. my legs had turned blue up to the knee. It didn’t matter, said my father kindly, unless of course they do the Can-Can these days. Panic set in, and I removed shoes, stockings, and scrubbed my legs to their original purple and the shoes to their off-white. To hell with co-ordination, I wasn’t going to let people think I had painted myself with woad.

By 8 p.m. I pitied my drab parents and my pathetic family who were not all glitter and Stardust as I was. They were tolerant to the degree of not commenting on my swollen ears, which now couldn’t take the diamanté clips and luxuriated in sticking plasters painted blue. They told me that I looked lovely, and that I would be the belle of the ball. I knew it already, but it was nice to have it confirmed.

(***)

There is no use in dwelling on the formal party. Nobody danced with me at all except in the Paul Jones, and nobody said I looked well. Everyone else had blouses and long skirts, which cost a fraction of what the alterations on my cousin’s evening dress had set me back. Everyone else looked normal. I looked like a mad blue balloon.

I decided I would burn the dress in a bonfire in the garden that night when I got home. Then I thought that would wake my parents and make them distressed that I hadn’t been the belle of the ball after all, so I set off down the road to burn it on the railway bank of Dalkey station. Then I remembered the bye-laws, and having to walk home in my underwear, which the baby sister had rightly said looked better than the dress, so I decided to hell with it all. I would just tear it up tomorrow at dawn.

But the next day, didn’t a boy, a real live boy who had danced with me during one of the Paul Joneses, ring up and say that he was giving a formal party next week and would I come? The social whirl was beginning, I thought, and in the grey light of morning the dress didn’t look too bad on the back of a chair. And there wasn’t time to get a skirt and blouse and look normal like everyone else, and I checked around and not everybody had been invited to his formal party: in fact, only three of us had.

So I rang the mother of the cousin again, and she was embarrassingly gratified this time, and I decided to allow my ears to cure and not wear any earrings, and to let the perm grow out and to avoid dyed shoes. And a whole winter of idiotic parties began, at which I formally decided I was the belle of the ball even though I hardly got danced with at all, and I know I am a stupid cow, but I still have the dress, and I’m never going to give it away, set fire to it on the railway bank, or use it as a duster.

12 December 1971

Nell McCafferty

First Dance

The most humiliating years of my life were those in which I tried to be beautiful. An attractive dame I was not. That my childhood was not ruined by the fact that I had (and have) bandy legs, short stature, yellow bilious pimples and no waist at all is due entirely to my father. He called me “Curly Wee”, carried a picture of me everywhere, and used to read my school essays to his workmates.

I had a very attractive older sister who wore clothes like a model, could jive like Elvis Presley and had callers at the door. When they did call and I remained behind, my father would engage me in intellectual discussions about greyhounds and odds-on favourites and the amount of fuel required to fill the ships of the Royal Navy, in which exercise he was daily engaged.

When my brother and I went to our first céilí dance at the age of fourteen, my mother took my brother aside and reminded him to treat all women as if they were the Virgin Mary. My father took my brother aside and reminded him to treat me as he would treat all women, and thus I was always sure of at least one dance. If my brother did not dance with me, I went home and told my father, who took suitable punitive action.

Then there was acne. No amount of soap and water could cure it. I had pimples, blackheads, flaking skin, the lot. I was miserable. Nothing, I realize now, could cure it. It was one of those teenage things. But when we queued up every week for our threepence pocket money to be spent on gobstoppers, everlasting toffee bars and marbles, my father drew me quietly aside and slipped me the extra for a tube of Valderma, designed to give me skin like Marilyn Monroe. It never did, of course, but someone at least was backing me.

Brassières and breasts were always a problem. I once tucked my school blouse alluringly into my tennis shorts, and in the middle of the senior tennis championships when I was two points ahead, the Reverend Mother blew her whistle, summonsed me off court, and informed me that certain appendages stuck out which Our Lady would prefer to remain hidden. I lost all my points including the championship.

Hair, too, was a problem. When pony-tails were in, the best I could manage was long ringlets. Backcombing arrived and I went round like an unemployed Niagara Falls. As for hair on the legs and under the arms! The muffled whine of my father’s electric razor used to bring my mother roaring up the stairs, and I was always left with half a hairy leg and one bare underarm. I resorted to the quieter manual razor and used to go to dances cut to ribbons.

It’s not that I have anything against beauty treatments, or beautiful people. It’s very nice to see pretty people around the world, and I like to look at pictures of the Taj Mahal and the Acropolis, and Sophia Loren and Paul Newman. But the best I can manage is to wash my hair regularly, to stop biting my nails, and concentrate on my eyes, which are a rather nice shade of blue.

Otherwise, the hell with it. If I saved up the money I’m advised to spend on beauty treatment and went abroad I could get a great suntan which would offset my eyes. Also, I could go swimming, which is better than beating myself about the breast every morning.

So there.

14 October 1971

Mary Cummins

All Our Easterdays: New Dresses, Picnics, and a Retreat

With purplish-black ink greasing up my calloused fingertips, I’ll be working all over the weekend. My soul soaked in nostalgia and the might-have-been-if-I-had-used-my-loaf. Dutifully, and with a mournful face, I will remind one and all that I am an Easter martyr.

I will remember, teardrops from my craw, changing into summer dresses and the new one for Sundays coming in a brown box from Clerys. A clean church and unfamiliar, eerie statues under purple. A white altar with stark, majestic lilies, white and pure at midnight Mass.

Remember, incongruously, a dancing teacher coming in a big car the day we got holidays. She took the money we were sent home to get for lessons and was never seen again. Remember, remember, fast days and two collations and a mound of saved sweets grown under sweaty, longing glances: gifties, and dandys and cough-no-mores.

Remember Spy Wednesday, a sinister day and sloes on bushes. The silence at three on Good Friday, and the clack, clack of the wooden clappers at the Consecration instead of bells. That morning, the first day for picking periwinkles, patches of people on the strand from early morning with buckets. Concentration. Bending and straightening and putting stones in to heat the others. The swelling smell as they boiled their lives away in a big pot that evening; the sandy scum at the top of the grey, murderous water. We watched and waited with needles poised.

Smell of grass, luxuriant and fresh, and a picnic on Easter Sunday afternoon back in the sand hills. The girl who didn’t get any Sunday money taking a tin of peaches so that she could come. Following the courting couples to work off the layers of sugared bread. Forgetting the time in the first burst of summer evening.

A retreat at school the week after Easter and long holy days getting longer and holier, with heaven and hell and the lives of saints and of mysteries sordider-than-thou tunnelling home to confuse further. And long walks on the cliffs wrestling with a vocation, unable to disbelieve those who said you’d never be happy if you turned it down.

One Easter egg for the five of us and the envy of the friend who had one to herself. Easter is a resurrection, a stone rolled away from a tomb, and a God-man steps out. Easter is a stuffy room and a glimpse of freedom, a long empty beach, boiled eggs for tea, a restful sea in the blue sky above the chimneys on the way to the bus.

31 March 1972

Mary Leland

Two Marys Go to the Dance

The last bus to Blackrock, Cork, gets crowded on a Saturday night. The girls and boys upstairs sing in competition with the girls and boys downstairs, and to the alarmed senior citizens it sometimes seems as if the bus is swinging in rhythm.

The singing upstairs is invariably begun by a group of five or six undersized and possibly undernourished girls, lively and in happy unison. Whatever about anyone else, they are heading for a dancehall. They sing all the way from the Statue, joined at Ballintemple by the rejects from Constitution and outsinging them too. They swear tunefully that they’ll never fall in love again, they beg not to forget to remember them, and not to say goodnight, midnight.

Old ladies with queasy poodles avoid the robust eyes of elderly men, normally sedately sober, but who at some time after eleven on a Saturday night are amorously drunk. Girls in their college scarves get off gratefully at Beaumont and the bus conductor asks them, “Would you like to be going dancing with that crowd?”

The singing girls—little, thin, deliberately eyebrow-less, and still wearing cotton dresses and light nylon raincoats in December—clatter off up the road. The boys stand with hunched shoulders among those who have just left the pub. Inside the hall, in the lights and the warmth and the excitement, the girls sit together in the corner nearest the bandstand, smoking and listening. They never dance unless weaving around their corner with one another. Otherwise they sit drinking in the music and the songs, until it’s time to go home. Then linking arms they walk back to the city, spread out across the width of the Marina, singing through its blackness by the river’s edge: “Good Morning Starshine…”

I used to love that bus. But one night the girls screamed and bolted down the stairs in an attempt to make the driver stop. There was a fight. There was a knife. There in the back of the upper deck struggled a heaving, shouting mass of young bodies. Conductor and driver raced up and seemed to be sucked viciously into the melée. The noise, curses and the sounds of blows combined in a terrorizing, sickening nightmare; the bus became a double-decker coffin full of hate and curses and savagery. Some of us got off, rang the gardaí and from outside watched with dry mouths and shivering hearts the heads being knocked against seats, wild arms reaching to clutch. Somehow the busmen, struggling up from between the seats, pushed enough of one faction away with them, down the stairs and out onto the road to be able to close the doors against them. A boy leapt against the glass, swinging his chain. The girls moved back upstairs, the singing began again and the bus moved off. And I walked the rest of the way home.

(***)

The Stardust Club: public dancehall on the Grand Parade, admission usually around eight shillings, except for Sunday afternoon “teen” dances when it’s three shillings and sixpence. I went to the Students’ Dance on Friday night, with Tina and the Mexicans providing the music. The dances are well managed and organized, with scrupulous officials scrutinizing the queues for signs of drinking or drunkenness. It must be one of the most comfortable dancehalls in Munster, with recent conversions providing an armchaired lounge and balcony, where everybody watched the Rowan and Martin laugh-in on television for half an hour or so. From the balcony, the hall below—dimly lighted and tight-packed—presented a picture of an immobile throng. The slow dances here are very definitely slow, and during some of these it is hard to believe that anyone is moving at all.

In a slow dance of this kind the boy and girl, or man and woman (girls from sixteen to twenty-five, boys in the same range with some up to and over thirty) stand as close as physically possible, with the girl’s arms around the boy’s shoulders and his arms around her waist. The shoulder grip keeps both heads within kissing range, a position taken obvious advantage of, while the waist grip keeps the bodily pressure on. Thus held together, they move over a few square inches of floor, to break apart at the end of the dance and take up the same positions with someone else for the next one.

Nobody pretends any more not to know what “close dancing” is all about. It’s impossible to avoid its physical significance, and from what I could see no effort is made to do so by anyone. It’s just an accepted alternative to the fast dances, and sex, of course, has nothing to do with it.

The rule of “no pass out” avoids the quick court in the car and then back to the dance for another girl, but the philosophy persists. And the bright little faces of the girls telling one another that they’re fixed up for a lift home reflect not just self-congratulation at a successful night but a kind of permissive anxiety.

In the cloakroom, teasing their hair to new heights, they hurl information to one another—what’s he like, is he “alright”, did she know what to do, what happened last week? And in a welter of giggles they scramble out to take their chances. The crowd is mixed—the college cachet seems to mean very little. The band is electronically identical with all the others, even to the three-deep row of worshippers who never move from the footlights. Tina fingers her Apache headband like a tired nun and the music bellows its echoes of love and longing to all the young people who have nowhere else to go.

It isn’t all fun. At the ’Dust, at the “Con” (Constitution Rugby Football Club), just as at the Boatclub, the Shandon, the Arc, the Island, the Majorca, the Orchid, the Lilac, the Majestic and the Industrial Hall in Clonakilty, the girls stand patiently in line and the boys take their pick. Of course a girl can refuse the grip on her elbow, the muttered suggestion, the toss of the young male head. I saw quite a few doing so. But there is still the element of the slave or the cattle market. For a short while one night I remembered just what it felt like, felt the ache of the smile on my face. “It’s better to look dejected,” a friend said. “They seem to take pity on you then.”

But it’s a bruising, unfunny experience. The girls stand patiently in line and the boys take their pick. Most girls have no option. They don’t pretend not to be there to find a boyfriend. Because they’re there, they have to let themselves be picked up or discarded in a mass submission to masculine will. Only a few couples continue to go dancing once the partner is found. Some girls rejoice in the competition, in the challenge and in the trophies. Others retire from the field, congratulating themselves on having escaped a back-seat pregnancy, bitter at their chosen isolation from a throbbing vivacious contact with other young people, but unwilling to take any more chances.

They are bewildered that their worth hasn’t been recognized. It takes years to lose the innocent enjoyment and hope, and I can’t help continuing to believe that dancehalls should be gay and happy places. Perhaps they are; perhaps they only seem sad to me, with ten years between my contentment and their strife.

14 January 1970

Christina Murphy

First Love: Teenage Idol

I was pushing my bicycle up Chapel Hill after school, exchanging gossip with my best friend, when somehow we found ourselves confiding in each other who we wanted to marry. We must have been about fourteen, and we had been well and properly drilled by the nuns in such matters. We didn’t say we had a crush on him, we didn’t say we fancied him or that we’d like to have a court with him. To a convent-educated girl, men meant one thing—marriage. So when we fell in love, even at long distance, we automatically assumed that it meant wedding bells.

I had worshipped him from afar for some months, and I still remember vividly the relief of discovering that my best friend was in the same predicament. The joy of actually being able to mention his name, and in connection with myself, was almost unbearable after all those months of silent suffering. After a long chat about the relative merits of the two candidates and our possible prospects, we went home glowing with the cosy feeling of a shared secret and I think we thought ourselves half engaged already.

There followed a period of passing little notes to one another in class, composing poems in which the loved one featured surreptitiously, and toying with various combinations of the spelling of his name on the back of our Latin grammar.

She fared a bit better than I did. Hers actually danced with her on a few occasions—and I think he even kissed her on the cheek once at a Christmas party. I was doomed to engage in unrequited love for what seemed like years. He was undoubtedly good-looking, tall, thin and athletic with a great shock of black hair. But he was aloof and more interested in tennis and football than in girls.

I proceeded to adopt the most extraordinary tactics. I cycled home from school by twenty different routes vainly trying to get a glimpse of him. I began to take a loving interest in his little brat of a sister and gave her rides on my bike and bought her ice cream. I bewildered my family by suddenly becoming a religious maniac.

I went to eight o’clock Mass and communion every morning for two reasons: to pray to God to make him fall in love with me, and to position myself strategically near the top of the left-hand aisle, from whence I could watch him praying with bowed head and get a good look at him coming reverently back from the rails. I even toyed with the idea that he might be thinking of the priesthood and I was sure that if he did I would never marry anyone else.

(***)