Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Lebensstil

- Sprache: Englisch

By 1966 the steam locomotive was entering its death throes: withdrawals were being carried out at a frenetic pace, with the slightest defect sending engines straight to the cutter's torch. In an attempt to capture the British steam scene before it was no more, teenage enthusiast Keith Widdowson made it his mission to travel the length and breadth of the country to obtain runs behind as many locomotives as possible. Armed with a Southern Region season ticket and enjoying the camaraderie of fellow devotees, Keith quickly amassed many catches and great mileage, but countless overnight and lengthy expeditions to the north of England and Scotland throughout the summer of 1966 were needed to complete the picture. With a multitude of photographs, maps and notebook extracts, Chasing Steam in 1966 is a window into a bygone age. Join Keith on his 47,000-mile journey that takes in the demise of the Somerset & Dorset and ex-Great Central lines, and showcases the hunt for the handful of remaining Jubilees, capturing all the joys and frustrations of a great steam chase.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 152

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

When travelling out of Marylebone on the 14.38 Nottingham Victoria train on a Monday to Friday, one could observe, here at Rugby Central, the locomotive working that day’s 17.20 Nottingham starter. If she was, as in this case on Monday, 13 June, a ‘requirement’ (as Banbury’s 44860 was) I alighted there to catch it.

Every effort has been made to check and acknowledge the contribution of any copyright holders. In the event of any omission, please contact the author, care of the publishers.

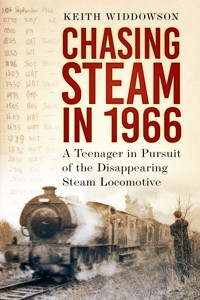

Cover illustrations: Front: A run-past featuring 0-6-0ST WD196 Errol Lonsdale; Back: Jinty 47202 fitted with condensation equipment for tunnel working in London.

First published 2024

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

© Keith Widdowson, 2024

The right of Keith Widdowson to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 520 5

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

About the Author

Introduction

January

A Cold Commute: Waterloo, Woking & Wessex

February

The Somerset & Dorset Dies: Fawley, Bath & Brighton

March

March Madness: Shrewsbury, Exeter & Carlisle

April

Pastures New: Windermere, Manchester & Longmoor

May

Tangerine Travels: Yorkshire, Leicester & Birkenhead

June

The Alnwick Adventure: Northumberland, Carlisle & Blackpool

July

Jubilee Joy: Barnsley, Bridlington & Aberdeen

August

Brit Bashing: Crewe, Preston & Edinburgh

September

Wavy Line Wanderings: Stranraer, Llandudno & Dorset

October

Autumn Outings: Lymington, Goole & Bradford

November

Rail Tours Galore: Stratford, Bacup & Weymouth

December

The Southern Sojourn: Shanklin, Kensington & Hampshire

Appendix

Glossary of Abbreviations

Sources

Acknowledgements

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Keith Widdowson was born at St Mary Cray, Kent, and having attended the nearby schools of Poverest and Charterhouse commenced his forty-five-year career with British Railways in June 1962. Including locations such as Waterloo, Cannon Street, Wimbledon, Crewe, Euston, Blackfriars, Paddington and Croydon, most of it was spent diagramming locomotive and train crews.

After spending several years in London, Crewe and Sittingbourne, he returned to his roots in 1985, where he met Joan, with whom he had a daughter, Victoria – and he recently became a grandfather to Darcey. Having had several books published on his travels in both the UK and Europe, he spends time gardening, writing articles for railway magazines and is a member of both the local residents’ association and the Sittingbourne & Kemsley Light Railway.

INTRODUCTION

The year 1966 was dominated by the lead-up to the winning and celebrations after England’s triumph over West Germany in football’s World Cup. While I’m not denying it was a historic event in MY world, a matter of greater importance was taking place – the demise of the steam locomotive. For over 100 years, the dominant power on Britain’s railways was being discarded in favour of a more innovative, less labour-intensive diesel or electric-powered substitute.

I had joined British Railways (BR) in the June of 1962 and, I have to admit, I knew very little of the political machinations involved in attempting to turn around the heavy losses being incurred by this nationalised industry. My mother, God bless her, had picked up on my interest in timetable reading and wrote to BR asking if there was a job for me – my daily commute to school involved a bus journey and the need to understand the relevant schedules in order to arrive on time. As an aside, this fascination with timetables led to many outings with my younger brother, utilising either the Green or Red Rover tickets, which allowed unlimited travel on London Transport routes at weekends – essential planning was needed, especially on the country routes, to avoid being stranded for hours. At this point, although I was never a trainspotter, I must confess to being the equivalent regarding London Transport buses.

Having passed the medical and clerical exams, I was allocated a position in the fourth-floor offices at Waterloo, in effect as the office gofer. This was, retrospectively, a wonderful initiation into the world of work. For sure, I made the tea, but I also ran errands for all and sundry all over the vast station. A perfect illustration of life back then is John Schlesinger’s 1961 British Transport documentary film Terminus – depicting twenty-four hours in the everyday (and night) activities to be found under the cavernous roof.

I witnessed it all. From the West Indians arriving via Southampton as part of the Windrush generation; the shoe shine boys; the down and outs using the seats as overnight accommodation; the lengthy, winding queues under the triangular signs suspended from the roof for the Summer Saturday trains to holiday destinations, and the alcoholic aroma emanating from the Leake Street vaults, to visits to the station-announcer’s panoramic periscope-like viewpoint just under the roof and making numerous trips to obtain as many ‘freebies’ as possible whenever a promotion (usually food orientated) stall was on the concourse; and finally, queuing, at the manager’s behest, for first-day issues of postage stamps at the post office.

I was to be seen sunbathing during my lunch break next to the beehives on the roof – avoiding falling from the edge (without any guard rails) onto the extensive glass roof covering the concourse. I also made visits to the Bill Office, which was in the arches adjacent to Waterloo Road, to collect leaflets for excursions or cheap day offers. The manager there often gave me a copy of station posters depicting the latest tranche of closures – examples being Hurstbourne, New Romney and the Cowes and Ventnor sections of the Isle of Wight system.

Having sometime during 1964 been moved to a different office, I was ‘awarded the honour’ of setting up a tea urn on the ‘Camping Coach’. This was to be positioned during off-peak hours at one of Waterloo’s twenty-one platforms to promote the use of them to prospective customers – they were mainly located at several New Forest stations. ‘So what?’ you might say. Now, here’s the thing. The coach was located in the North Sidings and was to be shunted via West Crossings to a platform. Having walked over to it before the move, I managed to obtain footplate rides from the friendly crews on a couple of Standard 3MT tanks and a West Country (WC) smooth-cased Calstock.

It may surprise readers to know that I was one of the rare species within the clerical grades who had joined the railways unaware of the associated travel perks. I was surrounded by clerks and managers, the majority of whom had specially joined BR to further their hobby utilising the free passes and reduced fares to travel the country taking photographs of closing lines and the disappearing steam locomotives.

Slowly but surely, the addiction began to take hold. Initially visiting lines threatened under the 1963 Beeching axe, the majority of which were still steam operated, I began, from the March of 1964, to document my travels. Following each outing, I transferred information that I had gleaned and scribbled down in my accompanying travel-worn notebooks into an A4-sized diary. Without this foresight, books such as this could never have been compiled, the minutiae of each journey being far too great to be drawn out of my memory bank.

A regular stroll around Waterloo Station, having had lunch in the staff canteen adjacent to Platform 15, included a visit to the country end of the lengthy Platform 11, to admire the preparations involved for the usually Merchant Navy (MN)-powered 13.30 Weymouth departure. The steam locomotive, I came to appreciate over the years, is a temperamental animal. She must be treated with respect for the crew to obtain the best out of her. Often in a worn-out and rundown condition, and covered in grease and oil, these unpredictable beasts required multi-skilled crews whose talents still, to this day, amaze me. The intoxicating aroma associated with these iron horses still sends shivers down my spine and, on the rare occasions these days of obtaining a run with one that I’ve never travelled with, the orgasmic euphoria stays with me for days afterwards.

As this book deals specially with the year 1966, I will now bring the reader up to speed as to where I was within the BR employment hierarchy. I was unsure as to which way my career was heading. Having been bored senseless by attending an evening class dedicated to progression within the ticket offices, I switched to a Rules & Signalling evening class, which was held in the Mutual Improvement Class (MIC) room above Clapham Junction Station.

Regrettably failing to comprehend the importance of understanding block sections and semaphore signals – and citing the fact that the future lay in coloured light signals – the lure of a Tuesday night trip on the ‘Kenny Belle’ (a sobriquet bestowed on this unadvertised service by enthusiasts) to get me there from my Cannon Street office morphed into diverting to Waterloo for the 18.00 and 18.09 steam departures. At least the Cannon Street job, involving journal marking, performance statistics and analysis of train running, gave me an increased income, thus allowing me to travel on numerous rail tours that year.

That November, having obtained further promotion within the clerical grades with a position at Wimbledon, I was to finally achieve job satisfaction: that of locomotive and train crew diagramming, which was to see me through most of my career within the railway industry. By 1966, I had morphed from a track-basher, racing around the country to travel over as many doomed lines as possible, to a haulage-basher intent on catching runs with as many steam locomotives as possible.

To those who have purchased this book without realising what terminology such as the frequently used ‘required’ means, let me explain. While any run behind a steam locomotive was welcomed, the addictive obsession of obtaining a run with a locomotive that I had never travelled with before (and therefore was ‘required’) was a haulage-basher’s objective – the capture being euphorically red-lined in whatever dog-eared Ian Allan Locoshed book was the current issue.

To this end, as can be read within the first couple of paragraphs of this tome, the Southern Region allocation was homed in on. Following that completion, I spread my wings throughout the UK mainland, coming across many like-minded devotees from many parts of the country. Upon such meet-ups, information (don’t forget, it was in pre-Internet days where any publishable information was not seen until months after the event) was readily exchanged as to which trains remained steam-hauled, which had succumbed to diesel, what sheds were closing, etc. This was where the camaraderie came to the fore. We came from all walks of life, not all being railwaymen and therefore not all enjoying the travel perks such as mine. There again, with no automatic barriers and less-frequent ticket checks, who cared?

I had missed the King and Castle classes out of Paddington; I had missed the School classes out of Charing Cross; I had missed the Brits out of Liverpool Street; I had missed the Duchesses out of Euston; I had missed the Gresley Pacifics out of King’s Cross; I had missed the Scots and Jubilees out of St Pancras and so I was left with the scraps. Hitler’s forces had incarcerated my father in a prisoner-of-war camp for many years, otherwise I would have perhaps been born earlier, but it is what it is. I made, albeit belatedly, the best of it and here is the result.

It was sad to see the steam locomotive in its death throes but, somewhat selfishly, I’m glad I witnessed it. It was a slightly ghoulish hobby, being in at the end of the giants of the Industrial Revolution; after all, we teenagers were never going to get old – we were going to live forever and getting old was a lifetime away. Well, here it is now.

Ironically, courtesy of people such as Dai Woodham, the steam locomotive will outlive us all. The burgeoning number of preservation societies with their dedicated bunch of volunteers have saved over 300 examples for future generations to enjoy. Well done them!

Another plus over recent years is the acceptance of trainspotting as an eccentricity not to be ashamed of – TV programmes featuring Chris Tarrant, Michael Portillo and Dan Snow have furthered the cause. Then again, with The Flying Scotsman centenary celebrations in 2023, she was never out of the news.

A concerted effort was made by this teenaged author in love with steam to obtain runs behind as many of them as the monies (of a junior clerk) would permit. With financial responsibilities such as mortgages/debts and the distraction of the opposite sex yet to kick in, the world, as I saw it, was my oyster. All corners of the BR network that still retained passenger trains hauled by the fast-diminishing iron horse were visited. The last runs of disappearing classes on closing railway lines – all were in the mix.

With more and more routes having just overnight mail trains powered by steam, fifty-seven nights that year were spent away from the comfort of a warm bed. Here, the reader will find the results of that frenzied time. The disappointments caused by unanticipated diesel locomotives (DLs) turning up; the euphoria of an unexpected catch; and the comradeship (and rivalry) among like-minded colleagues. Statistically, my achievements that year are contained in the appendices.

For readers who were not around during that pivotal year, here’s what you missed. For those who were there, enjoy your own special memories.

JANUARY

A COLD COMMUTE

WATERLOO, WOKING & WESSEX

London’s Waterloo Station was opened by the London & South Western Railway (L&SWR) in 1848, replacing the original terminus of the line from Southampton at Nine Elms, a less than convenient location for customers requiring central London. Initially named Waterloo Bridge, in the never-to-be-realised hope of an extension further into London, the somewhat piecemeal disorder of buildings that had developed over the intermediate years were extensively rebuilt, with the Victory Arch to commemorate the fallen of the First World War being encompassed in 1922.

Woking (originally Common until 1843) was opened in 1838 as a station on the Nine Elms to Winchfield line, with the tracks being quadrupled in 1904 and electrified in 1937. Basingstoke was opened in 1840 upon completion of the route between London and Southampton – Great Western Railway’s (GWR) broad-gauge arrived in 1848, with L&SWR’s route to Salisbury completing the scene in 1857.

As mentioned within the Introduction, during the previous year I had raced around the country visiting closing lines and chasing classes of steam locomotives destined for the cutter’s torch. Under my nose, however, on my home patch of the Southern Region (SR), the gradual rundown of the steam fleet was gathering pace. To this end, to travel with as many SR-allocated steam locomotives as possible before their annihilation, I began to catch runs out of Waterloo on the plethora of steam-worked departures during the evening rush hour.

The choice, at the beginning of 1966, was fantastic. Stopping services to Basingstoke/Salisbury departed at 17.09, 17.41, 18.09 and 18.54. As for the main line, although the 17.00 and 19.00 West of England departures had gone Warship-operated, the truncated 18.00 service at Salisbury retained steam – nearly always a sparkling clean 70E locomotive. Then there were the Bournemouth/Weymouth trains of 17.23 (FO), 17.30, 18.22 (FO) and 18.30 completing the scene. Returning trains were the 18.39 arrival (15.08 ex-Bournemouth Central), the 20.25 arrival (15.50 ex-Weymouth) and the 20.29 arrival (18.35 ex-Salisbury).

With no Total Operations Processing System (TOPS) available to us back then, on most evenings an assemblage of diehard haulage-bashers (I include myself among them) turned up at Waterloo and travelled out on whatever train sated their needs – i.e., something new for haulage or for mileage-accumulation purposes. There was always a friendly rivalry among us in being the first to obtain the ‘magic’ 1,000 miles behind as many different Bulleids as possible.

A review of one of my previous books highlighted that some steam-age reminiscence-orientated publications are overwhelmed with locomotive numbers, but that mine do not suffer from this. I will, therefore, use the numbers only when necessary, e.g. when caught for the very first occasion.

During the previous year, according to notes I made at the time, the 18.39 arrival into Waterloo was diagrammed for the Merchant Navy (MN) class, having gone down on the 08.30 that morning. I learnt, however, from a fellow gricer just before setting off on the 17.09 ex-Waterloo on Friday 7th, that it was now an Eastleigh duty and, sure enough, a grimy ‘Flat’, namely 34086 219 Squadron, turned up at Woking on it.

Never judge a book by its cover springs to mind here. She attained a respectable 74mph through Hersham with her eleven-coach, one-van train. With rumours circulating (subsequently proving false) that the MNs were to be replaced by Duchesses or Britannias, and personally still requiring six MNs, I would have somewhat selfishly preferred one of them that cold, frosty evening.

The following Monday (10th) saw me catch 35003 Royal Mail on the 17.30 departure – the returning trains from Basingstoke were noted as coming in covered in snow and ice. History shows that Royal Mail was to throw off the unkind sobriquet of ‘Royal Snail’ that had been given to it by us enthusiasts in the final weeks of SR steam – with several runs exceeding 100mph.