Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

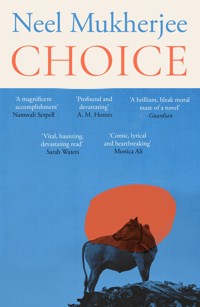

'A brilliant, bleak moral maze of a novel' Guardian 'Dazzling... by turns comic, lyrical and heartbreaking' Monica Ali 'Profound and beautiful' Paul Murray, author of The Bee Sting 'A vital, haunting, devastating read' Sarah Waters A publisher, who is at war with his industry and himself, embarks on a radical experiment in his own life and the lives of those connected to him; an academic exchanges one story for another after an accident brings a stranger into her life; and a family in rural India have their lives destroyed by a gift. These three ingeniously linked but distinct narratives, each of which has devastating unintended consequences, form a breathtaking exploration of freedom, responsibility, and ethics. What happens when market values replace other notions of value and meaning? How do the choices we make affect our work, our relationships, and our place in the world? Neel Mukherjee's new novel exposes the myths of individual choice, and confronts our fundamental assumptions about economics, race, appropriation, and the tangled ethics of contemporary life. Choice is a scathing, compassionate quarrel with the world, a masterful inquiry into how we should live our lives, and how we should tell them. 'A magnificent achievement' Namwali Serpell 'A superb writer... his greatest work yet' Michelle de Kretser

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 476

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Neel Mukherjee

A Life Apart

The Lives of Others

A State of FreedomAvian

First published in hardback in Great Britain in 2024 byAtlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2025 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Neel Mukherjee, 2024

The moral right of Neel Mukherjee to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

Excerpt from ‘Wild Is the Wind’ from Wild Is the Wind: Poems by Carl Phillips. Copyright © 2018 by Carl Phillips. Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux. All rights reserved.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 80546 050 3

Atlantic Books

An Imprint of Atlantic Books LtdOrmond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

Christopher

I

There cannot be a right life in the wrong one.

– Theodor Adorno

2.

Ayush has the less remunerative job, so he takes the children to school; as Luke says, ‘Economics is life, life is economics.’ As always, Ayush tries surreptitiously to scrutinize the faces of passers-by to see if some kind of knowledge imprints their faces, their eyes, when they pass him and the twins, a quantum of a pause, a double take, a second look to pull together a middle-aged South Asian man and two white-ish children into meaning, but no, he is spared today. After drop-off, Ayush takes the Tube to his office near the Embankment. He works for Sennett and Brewer, part of a vast international publishing conglomerate. Sewer, as it’s commonly known, is a self-styled literary imprint, as opposed to an upfront commercial imprint, of which the parent company has several. Self-styled because that’s the window-dressing. Behind the deceitful window, what everyone would really like to publish are celebrity biographies and bestsellers. But the performance of literariness is important and does vital cultural work (i.e. economic work): it pushes the definition of literary towards whatever sells. Ayush knows that the convergence, unlike the Rapture, is going to occur any day now. Maybe it has already happened, but he’s still here, playing the old game because it still has residual value. Soon it won’t. He is an editorial director at Sewer, second in command to the publisher, Anna Mitchell, a woman reputed to have ‘a nose for a winner’; in other words, that nous about how the convergence can be more effectively achieved.

He has never been able to shake off the feeling that he is their diversity box, ticked – the rest of the company is almost entirely white; all extraordinarily well-intentioned, of course, but stably, unchangingly white. The very few people of colour there belong to the junior ranks of IT and HR, none in editorial, apart from Ayush, or in management. The way the system works if they make any diversity hires is to leave them imprisoned in junior positions for so long that they eventually leave. Diversity is a gift in the giving of white people; they pick and choose whom they should elect to that poisoned club. Ayush was marked for the same fate until chance intervened. After four years as a commissioning editor – and, before that, three as the office envelope-stuffer (official title: editorial assistant) – he had got lucky with an author he had acquired for a fifth of Luke’s monthly take-home salary: Rekha Ganesan was shortlisted for the Booker Prize for her debut novel, In Other Colours. Not long after that, he had published, breaking the imprint’s ostensible mould, an upmarket crime-fiction novel set in the Punjabi communities of Birmingham. That had become a runaway bestseller and had scooped up a CWA Dagger and a Costa Novel Award. He heard the words ‘alchemy’ and ‘golden touch’ used of him; he knew that it was not because he was publishing good, maybe even important, work, but because these books were selling. Economics is life, life is economics.

A predictable state of affairs set in after these successes. Until that point, around 30 to 40 per cent of the manuscripts sent to him by agents, he would say, had been by writers of colour. That figure jumped to nearly 90 per cent. Anna complained that she only got books by white women on motherhood, the market for which, both on the supply and demand sides, seemed to be inexhaustible. It was true that she had not used the word ‘white’, but Ayush knew that the word he had silently supplied was accurate and could be easily substantiated by data: white women believed that motherhood was both original and endlessly interesting; a form of cultural narcissism. When he told Luke that his submissions from white writers had tapered off to almost nothing, Luke had said, ‘It depends on what was first coming through the pipeline. What was the proportion of POC and black writers you were getting before?’

‘Um, I don’t know. Maybe three to four non-white to six or seven white? Probably fewer.’

‘Maybe the success of POC writers leads to agents sending more to editors? Or more POC writers submit work and that doesn’t get ignored or buried. The market decides these things.’ Then Luke had proceeded to give him a lesson on ‘herding’ and ‘information cascades’.

‘You mean stereotyping, when it’s at home?’

‘It’s efficient, if you come to think of it.’

This had, of course, led to one of their usual rows.

Today, from 8:45 a.m. until 10, he has spent the time at his desk sharpening all the seven pencils – always odd numbers – to murderous points, moving them from the right side of the desktop monitor to the left, then back again, nineteen times, to achieve symmetry with the pen-holder – again, seven fountain pens – but the perfect arrangement eludes him, as it does most days, so he sets about clearing the entire desk and hiding the contents in the metal cabinet below. This is easily done as there isn’t much on the desk in the first place. Then he feels the air around Rachel, who sits on his left, and Daisy, on his right, take on that peculiar charge when the young women make a special effort not to look in his direction. On his notepad, he sets down a bullet point and follows it with ‘Which more water, washing single portion of strawberries or cherries, or w/ing entire punnet in one go?’ He makes the mistake of looking at both Animal Clock and Kill Counter on his computer before he heads to the meeting room. His breath races with the rhythm and speed of the numbers ratcheting up, as if his respiration is in competition with it. The list is headed by fish, which is already in the seven figures the very moment he opens that page and advancing five figures, in the tens of thousands, every fraction of one second. What goes up every full second is buffalo, which is number 15 of 17 on the list, arranged in descending order of numbers slaughtered: from wild-caught fish, through pigs and geese and sheep and cattle, to ‘camels and other camelids’. The clock begins the moment the page opens: it says, ‘animals killed for food since opening this page’. Luke would be pleased: he believes in the truth of numbers over the truth of representation. Ayush closes the tabs to stop himself from hyperventilating.

Ayush acquires around ten to twelve books a year; for the last three weeks, he has been pursuing a submission, a debut by an author called M.N. Opie. The agent through whom the work has arrived, Jessica Turner, knew so little about the writer that she seemed surprised not to have an answer to even the most basic question about whether Opie was a man or a woman.

‘I don’t know,’ she had said when he called her. ‘The thought never crossed my mind … I had assumed that he is a he, if you see what I mean. But now I’m not so sure. Let me find out.’

Each story in Opie’s short-story collection is different in subject matter, setting, featured characters and the points in the social spectrum they are lifted from, and, notably and subtly, in style. There is one about Richard Johnson, an elderly Jamaican vegetable-stall owner in Brixton, and the steady, casual, unthinking abandonment he faces from everyone, from the bureaucrats in Lambeth Council and the local Jobcentre Plus to his grown-up son and white daughter-in-law, to his customers who begin to move their business to a fancy organic store a few metres from his shop. Only his ageing, arthritic, halitosis-ridden coal-black dog, Niggah, is faithful to him. Then one day the dog goes missing. On the final two pages of the story, the man walks the length and breadth of Brixton, from Coldharbour Lane to Loughborough Junction, down Railton Road to Brockwell Park, shouting ‘Niggah! Niggah!’ The passers-by take him to be yet another black person with mental-health problems that Brixton is notorious for. The page had blurred for Ayush as he reached the end.

There is a long story about a young Eng. Lit. academic named Emily – an early modernist, no less – in a London university who is in a car accident returning home from a dinner party one night. The driver of the car is not who the app says he is. A combination of inertia, procrastination, and maybe even an inchoate strategy only half-known to herself sends Emily’s life in an unpredictable direction. Everything about the story is unexpected and it is not the plot. It is the inner voice of the protagonist, the representation of her world of work and her mind. Even this is not the most salient thing about it. Ayush tried, and repeatedly failed, to put his finger on the elusive soul of the story. Plot-wise, it seemed simple enough, but the more he thought about the underlying moral questions that propelled it, the more complex and troubling it became. In fact, entirely unwritten in the story was its chief meaning: how no escape was offered by making what one thought was the correct moral choice. That meaning appeared only in the echo of the shutting door after he had left the story’s room. And that room itself: a trap, a claustrophobic chamber of the protagonist’s mind from which there’s no escape. The prose sat at the exact opposite end of the scale from the story of Richard Johnson and his dog Niggah.

Ayush had felt an urgency he had not experienced for a long time. It was a physical feeling, something in his racing blood and in his stomach, in the heat in his hands and feet. He used to be derisive of the passing phases of editors’ rejection letters to agents – for a while, it was ‘I loved it, but I didn’t fall in love with it’, then it was, ‘It did not make the hairs on the back of my neck stand on end’ – but now he understood that, behind the congealed bullshit, there might, once upon a time, have been a real physical sensation. He felt that sensation while reading M.N. Opie’s Yes, The World. He had to publish this book.

Ayush has to get the book through the acquisitions meeting this afternoon and he needs to have all his cards ready. He has shared the manuscript with colleagues already – with Anna, of course, but also the director of the paperback imprint, Juliet Burrows, with the sales director of the division, the marketing people (all men), the publicity team (all young women) – and talked it up, making sure to tick all the necessary boxes instead of actually talking about the literary and, to his mind, quietly explosive qualities of the book. So he had discussed the collection in terms of comparison titles (‘as thunderclap of a debut as White Teeth or Conversations with Friends’; he had really wanted to say Lantern Lecture or Counternarratives but he knew that he had to hit topical, buzzy books that were being talked about right now, for ten or even five years earlier risked blank looks), talked up projected sales figures (‘I think we could be looking at a bestseller like Queenie or You Know You Want This’; the collection was light years away from those reference points in every imaginable way). Later today there would be the usual cavils about short stories, the usual deliberate confusion between what sells and what is a good book.

There are five other books presented at the meeting by other editors before it’s Ayush’s turn. One book, by a ‘mid-list’ American writer, is turned down because ‘there really is no place for yet another quiet, beautifully written literary novel’. An Israeli writer, whose first three books in translation they have published, has his fourth declined because the sales record is poor. Everyone has done his or her homework in the only domain that matters here: sales figures of past books. No mention of reviews, no mention of prizes, which, admittedly, have negligible traction on sales apart from one or two brands, no mention of reputation, the meaning of the work (this would be embarrassing to bring up), or anything that cannot be monetized (Luke would have loved publishing). Two non-fiction debuts are given the green light with almost indecent eagerness – one, a book on new motherhood, another on why the author made the ‘life-choice’ of not becoming a mother. Both by white women, Ayush notes; reproduction is clearly hot. The book on volitional non-motherhood is based on a blog, the commissioning editor says, and its growing popularity among younger millennials, attested by the author’s Twitter following, should assure high sales. There are the usual formulae to talk about books: ‘Come for The Handmaid’s Tale, stay for Bridget Jones by way of Derry Girls’, ‘Kafka meets Fleabag meets anti Female Genital Mutilation social activism’, etc. Some of these references pass over his head – Derry Girls? Fleabag? Such a fever of excitement, such hopes of having caught the zeitgeist by its throat. As he tries to dress the words inside him to demur in a way that would appear seemly at a meeting, someone else, someone junior, has the foolhardiness to murmur something, which Anna cuts short with her tart ‘High-minded books won’t butter any parsnips.’ He feels that she is speaking pointedly to him. Economics is life, life is economics. Several years ago, during the company’s Christmas lunch, Anna, after a couple of glasses of prosecco, had observed, ‘We just throw things at the wall and see what sticks. This isn’t a science.’ She thought she had been making a joke.

When Ayush’s turn comes, he leans forward and speaks of his book as the future of British publishing, the voice of a new demographic, diverse (the buzzy term used to be ‘multicultural’ when he had started out all those years ago), a voice as at ease with hip-hop and Brooklyn drill as with Dickens, a new voice, he repeats, ‘looking back to White Teeth in its vibrancy and to Ghostwritten and Cloud Atlas in the way discrete, disparate narratives come together cleverly to make a unified whole that we call a novel’, ‘a big-L literary work that is also a big-P page-turner’ – in moments of extreme despair, he has always fantasized about selling the last free corners of his soul and joining an ad agency – and it would be a terrible missed opportunity to let this book, ‘so of its moment and so timeless at the same, erm, time’, go to another publisher. If self-loathing had material form, like vomit, he would be an abundant fountain now.

‘Is there other interest? Are there any offers already?’ This from Juliet Burrows, Head of Paperbacks. Of course. No industry is run more by herd behaviour than publishing: we want this book because others want this book, so there must be something in it, but we are not capable of discerning first, we’ll take cues from others. Would Luke have called this a signalling game? Two years ago, a novel Ayush had acquired for a substantial sum, a book everyone had been impressed with, had had its marketing budget reduced to nothing, effectively killing it, when the chief fiction buyer of the biggest bookshop chain had decided not to ‘get behind it’. Whereas before, it was a book everyone had ‘believed in’, or said they had, it became, overnight, something like a leper who had walked in from the gutters and stationed himself in the middle of the office: everyone felt embarrassed, full of pity and aversion, and walked in a wide radius around the leper, refusing to acknowledge his presence.

Ayush is prepared for Juliet’s question. He lies without the barest flicker: ‘I think Jessica said there was strong interest from’ – he reels off three names – ‘but no offers on the table yet. I’d like to try a modest pre-empt.’

There is talk of upper limits and caps. The sales director tweaks the P&L to make it work. Just; Ayush will have to buy it cheap.

Ayush runs out of the meeting to go to the toilets, shuts himself in a cubicle, and throws up. Afterwards, he spends twelve minutes scrupulously wiping, first, the top-edge of the toilet bowl, the seat, the seat cover, then, worrying that some of that acidy toast-mulch must have sploshed outside, the floor, in circles of increasing radius around the squat stand of the toilet bowl. Then he thinks of the Edgar Allan Poe story, with the murderer wiping every surface at the scene of crime until the police break down the doors in the morning to find that everything has been polished to a gleaming high sheen, and stops.

3.

All night, he lies awake. At 3 a.m., he gets out of bed and puts the tube-squeezers that arrived in the post yesterday on their three-quarters-finished tube of toothpaste and on the children’s strawberry-flavoured one. Then he has an idea and clamps one on to the tube of tomato purée in the fridge and feels a tiny squiggle of satisfaction run through him, over before it can be savoured. Then he has another idea. He takes the largest mixing bowl (4.8 litres), puts it under the shower, and turns on the timer on his phone and the shower simultaneously. While the bowl is filling, he runs down to the kitchen to fetch a pencil and a small pad. He notes down the time it takes to fill the bowl and turns off the shower. Now he has a problem – what to do with the 4.8 litres of water? Tipping it down the plug hole of the bath is unthinkable. The cistern is full (although less full than it would normally be because he has put bricks, wrapped in the plastic bag that Thames Water had sent, in each cistern in the house). Wait, he knows. He comes downstairs with the full mixing bowl, careful not to spill, and goes into the kitchen. Spencer has followed him; he looks up at Ayush curiously, wondering at this change in routine, wondering if there’s a nice surprise in store – an unexpected exploration of the night garden or something culminating in a chase and a treat. Ayush says, ‘Shhh, we’re not going out. You stay here, OK? Stay. Sit.’ Spencer obeys. Ayush sets down the bowl on the countertop, unlocks the garden door, turns back, lifts the bowl, takes it outside, empties it into one of the two water butts, and returns to the kitchen, very quietly shutting the door behind him but not locking it this time. Spencer is consumed by curiosity – the smells of the outside have flowed in – but also content to sit where he has been told. Something is afoot; he’ll find out in time.

Ayush repeats all his actions, from the collecting and timing of water to disposing of it in the garden. His pad fills up with figures in two columns: time and volume. He lets Spencer out for a wee, then worries that this one-off toilet break will confuse him. ‘Come in, now, come in,’ he whispers, ‘back to bed, sweetheart. Bed. Come on.’

Then he goes to his study and begins the calculations and research.

By the time Jessica reports back, four months have passed, Ayush has formally acquired the book, and even the contract has been executed, not something that happens quickly. ‘I emailed to ask Opie for a phone number,’ she says. ‘He wrote back a very polite but firm note to say that he’d like all communication to be via email. I even asked about preferred pronouns, but that point was not addressed. I don’t know how to put this, but there was a wall somewhere in the email – it gives off a thus-far-no-farther vibe. I’ll forward it to you now.’ Ayush knows exactly why she is treading a fine line between feeling troubled and trying to appear to be breezy and unconcerned.

‘But what about publicity, when the time comes?’ Ayush almost wails. ‘I might get into trouble if I agree to this now. We aren’t getting ourselves into a JT LeRoy kind of thing, are we? Although, if this is a Ferrante kind of situation, we may get lucky.’ He finds himself walking her fine balance too and hates himself for letting This could be a gift, a new kind of publicity flit through his head.

‘What’s his or her name?’ he asks instead, tamping down his polluted thoughts.

‘Oh. M.N. In fact, another thing he made very clear in his email was that he preferred to be called M.N.’

‘But what do M and N stand for?’

‘He didn’t clarify. He signed off “M.N.”’

Ayush had already looked online, muttering, MNOpie, MNOpie, MNOpie. Nothing. A Catherine Opie in the US. Did you mean Julian Opie? The search results show … etc. Then he had laughed. Of course. He doesn’t mention any of this to Jessica now. Let it be his sort-of secret.

4.

It’s a Wednesday, so Luke’s turn to cook supper. Ayush always returns home early on Wednesdays to do the task of what he thinks of as pre-emptive damage control. He has had calculated by an amateur science blogger the difference in energy consumption between boiling water for pasta in a big pot on the hob and boiling several kettles for the same amount of water: kettle is greener. Ayush has measured out the pasta in a bowl and the exact amount of water to be boiled, the first of four batches, in the kettle. Left to his own devices, Luke would have set their biggest pot of water to boil, drained it all after the children’s pasta was cooked, then repeated the same actions for his and Ayush’s meal later – a scenario that keeps Ayush awake at night. Luke gives them sausages, diced into bite-size portions, and plain pasta with a curl of butter on top, and some petits pois (boiled in the same water after the pasta has been lifted out with a large-slotted spoon, not drained, since that water will be reused for the adults’ pasta). In Sasha’s case, the peas, sausages, and pasta are all served on separate plates since he does not like different foods to touch each other.

Spencer is under the table, as always, hoping for scraps. The children have refused to heed their parents’ repeated pleas and threats not to feed him. It’s a war that Ayush and Luke have lost, not with many misgivings.

Sasha pushes his plate of sausages away, taking great care not to make his fork touch the meat. ‘I’m not hungry,’ he announces.

Masha chimes in, imitating her brother, as she does in all things. ‘I don’t want this, I’m not hungry,’ she declares.

‘What’s up?’ Luke says. ‘You love sausages. Do you want ketchup on it?’

They shake their heads in unison, toy with their pasta, then begin to exhibit the usual crankiness that comes with exhaustion. Later, Ayush will think that he was not paying any attention to what was really passing between them, so he is shocked, more by the speed at which the act is executed than by the act itself, when Sasha lifts the plate of diced sausages and tips it under the table. Spencer wolfs it down snufflingly before Luke and Ayush can react. When Ayush looks under the table, Spencer is looking up at the children’s feet, his tongue out, gratitude and greed melting his eyes.

Luke, who never gets angry with the children, is puzzled first, at the swiftness with which things have happened, then irritated with the way he’s been taken in. ‘Why did you do that? Tell me, why?’ He’s trying to work himself up into a fury.

‘He is canny-vor-es, he eats meat because he doesn’t have a choice,’ Masha says, looking unblinkingly at Ayush’s face.

Ayush turns away, pours himself a glass of the mouthpuckeringly sour wine that Luke calls ‘bone dry’ and seems to like so much, and returns to washing broccoli, chopping garlic and chillies.

Luke still doesn’t understand what’s going on – he is like an actor who has been thrust onto the stage without having been allowed to see the script. ‘How many times have I told you that you’re not to feed Spencer? How many times? Do you understand that it’s bad for him? Would you like him to get heart disease and die? Would you like him to get fat and ill and suffer and die? Would you? Answer me.’

The children look as if they’re paying careful attention to each of his questions, which he delivers in a tone of calm reason, not anger.

‘Fine, you’ll go to bed without supper in that case,’ Luke says, failing to enter into anger and inhabiting, by his characteristic default, especially with the twins, a reasoned gentleness instead. Ayush marvels silently.

‘Bath time now,’ Luke says, and chivvies them up to the bathroom.

By the time Luke comes downstairs into the kitchen, his bath-time and bedtime-reading duties behind him, he looks like a cartoon depiction of bafflement, his brows furrowed, his normally clear blue eyes clouded. ‘What did you do with them?’ he asks. ‘They refuse to continue with Charlotte’s Web.’

‘What do you mean?’ Ayush grates generous amounts of pecorino onto their bowls of steaming pasta with white-hot attentiveness so that not a single wisp of cheese falls on to the table. Let there be a hundred more years of a better, a healing world, if the tabletop remains untouched by a single particle of cheese. He will go blind with concentrating.

‘They don’t want to hear a story about a pig who will be made into sausage. I couldn’t convince them that he is saved.’

Ayush makes some vague, non-committal tsks. He can tell that the children haven’t said anything of consequence to Luke, but he knows that it’s going to come in slow degrees. Now, Luke makes half a joke out of it: ‘If the kids turn vegetarian, you are dealing with their meals.’

Ayush says nothing. In the space of that silence, Luke works something out. ‘Wait,’ he says, ‘are you behind all this?’

‘What do you mean?’ Ayush repeats.

‘Are you indoctrinating the kids?’

Ayush takes a deep breath; if it has to be done, why not begin now. ‘I wouldn’t call it indoctrination. I think we should teach them about choices and their consequences. Certainly about things that don’t appear to be choices, things that are given to us as natural, things we fall into with such ease, such as what we eat, what we are trained to eat. I’d like them to question the so-called naturalness of that.’

Luke is silent for a while, assimilating. Then he says, ‘Sure. But it can’t become costly for us.’

In their twenty-odd years of being together, Ayush knows ‘costly’ is the econ-speak for not just the literal meaning of the word, but also for anything that is inconvenient. According to Luke, people simply won’t do things, or at least not in any sustained way that would make a difference, if you make it difficult or inconvenient, i.e. costly, for them.

‘There are more important things than convenience. If we all thought a little bit less about convenience, not a whole lot, god knows, I’m not asking for much, if we gave up just a tiny bit of our convenience, then maybe we wouldn’t be in the state that we’re in now.’

‘Whoa, whoa,’ begins Luke.

Thank god, he hadn’t said, What state are we in? Ayush thinks. ‘Most of us can agree on something,’ he says, ‘– the badness of eating meat or Facebook – but why are we unwilling to pay the private cost of giving those up? Why has the responsibility for action been shifted to the never-arriving public policy or, in your thinking, market solutions to make that large change? Where has the idea of individual agency gone?’

‘Because individual actions are low yield. Policing how much loo roll you use, going on marches, these things achieve nothing. The change needs to be on a different scale.’

‘You think American Civil Rights protests, for example, were low yield? Market solutions brought about the end of that discrimination, at least on paper?’

Luke hesitates. Ayush notices the gap and rushes to fill it in: ‘We are all so willing to follow the “no pain, no gain” dictum when it comes to improving our bodies, looking good, about all things feeding our general narcissism. What about “no pain, no gain” for the weightier matters?’

You must change your life.

‘The end of that line of thinking is good old socialism – everyone should have enough; if you have more, we’ll take it away and give it to others who have less.’

‘You’ve made several leaps, but I cannot see a moral argument against that principle.’

‘But a scientific argument there certainly is – there is no evidence to support your system.’

Again, Ayush has learned, over time, that this is a gussied-up way of saying that the arc of human nature bends towards capitalism and its foundational principle of ‘everybody wants to have more’. But ‘human nature’ is a term that’s unsalvageable, and in any case too fuzzy, too humanities-inflected, for economists, so they hide behind the more sciencey-sounding ‘evidence’. Evidence from where? What experiments or data or observation? How many people? How many experiments over time? In every country in the world or just the USA, the one country that has become the standard, especially in Luke’s discipline, from which everything about human nature is extrapolated? What is evidence? Isn’t it always already selective? They have clashed on these matters numberless times, and every single time Luke has pointed to socialism’s bloody history to clinch his argument, or rather, the argument he thinks Ayush will understand. It’s straying there again, the conflict of economic systems, the insistence that capitalism is science, not an ideology with its own very special, and unfolding, history of blood. Ayush, too tired to retread those paths, just says, ‘But greed isn’t turning out to have such a great history, is it? Besides, resources are finite – how long are we going to sleepwalk through life like this? Where has all your tribe’s fetishization of growth got us? And anyway, who’s talking about socialism?’

‘Not again, Ayush, not bloody again. Bleeding. Heart. Liberalism. May I remind you that the foundation of our discipline is to work out the allocation of resources, which we know to be finite.’

‘May I remind you who used the word “costly” a few minutes ago? I have to take Spencer out.’

That whooshing silence in his ears again. Ayush does not remember its origins, nor whether it began with the sound, as he hears it now, or with the accompanying image, which crosses his mind’s eye when the sound begins. A spherical cosmic body on fire, hurtling through the blackness of space, like a burning coal thrown against a pitch-dark background. The soundtrack, perhaps simultaneous with the image, is a simulation of what that ignited hurtle might sound like, what Ayush imagines it might sound like – like a whispering, a low susurration, a sighing of breeze, with the barest hint of a crackling here and there, almost imperceptible. Is that really what burning sounds like or is it an imagined stylization of the real thing? An approximation which is touched up and tweaked to seem real? Everything is approximation. This is the silence he hears in his ears, so different from the real silence of the world, which is not the absence of sound at all, but just a momentary stilling of the foreground while planes, buses, cars, people, pigeons, sparrows, dogs, children, construction, all with their specific sounds, carry on in the background.

Outside, in Crocus Park, Spencer and Ayush walk the perimeter of the pond, then Ayush begins to feel confined, and they head towards Herne Hill. The traffic is minimal on Half Moon Lane at this time of night: only one number 37, with its overlit interior. Spencer is surprised and overjoyed; this is going to be a real walk, longer than his usual final toilet break, a curtailed, half-hearted thing, whereas now he can smell the night and its creatures, almost present, shimmering and immediate, behind the undergrowth, not their dying traces in the daytime. Ayush too thinks of the flowers working at night, smelling different, more intense, more liberated, more obscene, somehow, than their polite, corseted daytime selves. There’s the enormous spreading pillar of the jasmine adjacent to the front door of number 41, which it seems to want to devour. The little bells in the small but spreading colony of lilies-of-the-valley near the steps leading to the door are now brown and over. The honeysuckle is out on the low front wall of number 43. Like Spencer, he wants to push his head into everything – even the foxgloves and geraniums and cistuses seem to smell, or want to smell, if he could only just shake off his human form and lower his head and nose into them. In the last available light, the sky is a shade of the ink his father used to call royal blue. Ayush can make out the briefest flitter of a bat across the jagged-edged canvas of that blue strung out between the dipped roofline and the fractals of treetops before it disappears into the orange flare of the streetlamp. The flowers are working to summon their friends, the big hairy moths and other insects of the night. A whole secret world, invisible to him, to other humans, thank god, a world awake with spinning, weaving, rustling, hiding, killing, devouring, fucking, spitting, marking, secreting, eating, a wild, violent world where, to put on Lukey’s hat for a moment, self-interest and unintended benefits and costs are inseparable, suffered or enjoyed asymmetrically, by different parties. Spencer can hear and smell the night’s dominion. There he goes, sniffing that low mound of fleabane growing out of a crevice in the boundary wall between 51 and the garage with great, slow intent, then raising his leg and sprinkling it with his piss. What would the moth coming to visit it think? What would it think, what would it think? Pay attention, pay attention, pay attention. How funny, that the verb for the only agency we have, the only thing left to us, the act of noticing, should be one of cost, as if you’re buying something in exchange. Lukey would be privately smug about it. If Ayush can step on every alternate slab on the footpath and get to the junction of Half Moon Lane with Milkwood, Norwood, and Dulwich Roads and Herne Hill without one false or extra step or break in his stride, then. If he can get to number 153 without a single vehicle going up or coming down the road, then. His breathing ratchets up. For here there is no place that does not see you. You must change your life. If the traffic lights ahead stay green until he hits the front door of the pharmacy, if Spencer doesn’t mark the lamp post whose base he’s sniffing, if, then, if then. Many years ago, before, before … before what? Anyway, many years ago, Lukey had once tried to explain to him how economists modelled the world, and Ayush still remembers the bit about how any proposition opened up a palette of possibilities – not Lukey’s phrasing – and then economists went down a series of if this, then thats, proving or disproving them one by one.

When Spencer and Ayush return home, Luke is in the bathroom, cleaning his teeth before getting into bed. He has left the tap running: Ayush can tell because he can hear the boiler in the kitchen humming. He whips out his phone and sets the timer – he’ll have to add a handicap, or whatever the term is, for the lost minutes before he entered the kitchen and before the idea to time the hot water struck him, say an extra minute or two – and starts cleaning the kitchen table to take him away, however feebly, from the threshing inside his chest. He wipes down the placemats with a damp dishcloth, sets them against the backs of the chairs to dry, each mat assigned to its own chair, then wipes the kitchen table in great sweeping arcs, equal number of arcs for each quadrant. He waits for the table to dry, then repeats the wiping exactly, the same number of sweeps, which he has counted (seven), for each quadrant. The boiler stops its music. He leaps to his phone: 2 minutes 38 seconds. Plus two (handicap or reverse-handicap?): 4 minutes 38 seconds.

Luke calls out, ‘Oh, I didn’t hear you come back’ – to which Ayush wants to say, to scream, to bellow with all the power in his lungs, ‘Because you’ve had the fucking tap running for nearly five minutes’, but concentrates on arranging the table – as he comes into the kitchen to find Ayush measuring the distance between each placemat with a plastic ruler so that they are equidistant from each other and in perfect symmetry.

‘Are the children asleep?’ Ayush asks in his calmest voice.

Instead of answering, Luke turns back to go upstairs, then thinks twice before re-entering the kitchen. He comes very close to Ayush, reaches out his right hand, and very gently brings it to rest on Ayush’s hand that is holding the ruler. Ayush can smell Luke’s toothpaste.

‘Please,’ Luke whispers. ‘Please. Can I help you stop this? It’s easy to get help for this, you know.’

Ayush feels too tired to fight back.

‘I’ve read up about it. It’s one of the things you can actually make better. Trust me. Tell me what I can do.’

Ayush is afraid of uttering a single word.

‘And,’ here Luke pauses, ‘and if there’s something underlying, and this is just the expression of that, it’s best to find out.’

That ‘underlying’ brings Ayush out of his enclosedness. Inside, his bitterness wells up into a very brief laugh, almost a snort. Something underlying, yes. He hears Luke saying, ‘If you’re unhappy at work, you can look for some other job. I want to help you. Please tell me how I can help you.’

The only way Ayush can stop Luke going on is to lean into him and let himself be enfolded.

5.

The day starts with a spreadsheet called ‘Daily Figs’: not the fruit, but numbers, figures. Economics is life, life is economics. A meeting to review Q2 sales figures, then straight to a meeting about metadata. Half an hour in between meetings to look at 231 emails. A meeting about sales-rep streamlining in spotty markets. Emails (this time about half of them between colleagues two desks, or one floor, or eight desks four metres two right angles away). Divisional targeted ads rationalization meeting. He thinks he has perfected clenched-jaw-shut-mouthflared-nostrils yawns to a degree that no one will notice that he’s suppressing them. (During the Zoom Era, he had caught himself stifling a yawn on his square of the screen, and it had looked so obvious that he set himself daily practice sessions to perfect it.) Emails (including from two authors asking for their sales figs, which they could find on the company website’s ‘Author Portal’ it had taken seven meetings within four hierarchies to design, and yet, now, Ayush needs to send a memo to ask this to be raised at the next Editorial & Publicity meeting to decide to inform all authors upfront so that it doesn’t eat into Editorial’s time). Meeting with the Production Manager to go through the coming year’s books. Jacket meeting to discuss new cover briefs with the team; Ayush never stays for other editors’ books, running out as soon as he has finished presenting his own. Meeting to discuss comparative digital revenue advantage over scaled-time sectors. Wow, someone from Editorial asks a question. The answer is a succession of PowerPoint slides with blue, green, pink histograms. A joke about data visualization; everyone laughs in a way that the only salient thing is the sound’s lack of energy and sincerity. Emails. Meeting for discounts for volume sales in online distributions. Meeting for distribution optimization in the bookstore chain. Recently, unconscious bias meetings, at which everyone looks at the floor, their inner selves caught up in a frenzy of eye-rolling, and Ayush feels a strange sensation, both superiority and a kind of low-stakes paranoia, as he imagines all his white colleagues hating him for the temporary edge his brown skin gives him at these meetings. Publicity meeting about emerging social media platform targeting. A different stripe of herd behaviour obtains here. Publicists work hard for authors who are already successful, well known; in fact, the more famous an author is, the more publicists work for them, the more attention these writers get, the more famous they become, in a nice, cosy circular feedback loop. Ayush had once dared to ask, in the years when his star was in the ascendant at Sewer, whether it wouldn’t be more equitable to redistribute publicity budgets. While everyone had instantly and in unison, as if directed by a choreographer’s cue, looked at their papers on the table, trying to find the meaning of life in them, Anna had declared, staring at the whiteboard with a kind of truculent energy, ‘We are talking about taking things to another level, not throwing good money after bad.’

Another level – that has stayed with Ayush. His work life has been an education in a recalcitrant knowledge: that publishers and authors are separated by an insuperable line. How can butchers and pigs be on the same side? As Lukey would have put it, ‘The interests of the two groups are not aligned.’ Many people loathe the jobs they have. Some go through with it thinking of the paycheque at the end of the month and all that they stand to lose without the money. Some go a step farther and delude themselves by learning to love the job, or certainly to perform a kind of love, becoming zealously supportive of the industry they are in, giving no sign or murmur of dissent or criticism, certainly not to those on the outside. Then there’s him, at war with wherever or in whatever he finds himself, never settling, or settling down, with what is given. Shouldn’t existence be a quarrel with all that could be better but isn’t? But what does it mean to not belong to your own side, to be at perpetual war with them, to remain perpetually on the outside? For him, it’s the only way to be, and the costs, as Lukey would put it, are enormous.

Meeting to discuss meetings about meetings. The real work, the work that Ayush had thought, years ago, he was getting into, the work of reading and editing, the work of ideas, of conversation – that work is no longer within work hours; it is part of his non-work life, which old-school Marxists, with what looks now like touching naïveté, used to call ‘leisure’.

Ayush is getting the children ready for school. Nothing is straightforward, least of all time.

He has put Cheerios into their bowls and two mugs of chocolate milk on the side before they’ve sat down at the table. Sasha tries to pour milk into his bowl, misses, and sploshes a generous amount on the table. It creeps and begins to drip down to the floor. He tries to move his bowl and spills half his cereal in the process, some of which lands in the milk on the table. Ayush goes down on his knees to wipe up the spill on the floor but Spencer takes care of it.

‘May I have sugar on my Cheerios, please, Baba?’ Masha asks.

‘Try it without, you like it,’ Ayush says.

‘I want sugar,’ she says.

‘I want sugar on mine too,’ Sasha follows.

‘What about a banana, sliced into rings? So you’ll have the big banana rings, fewer in number, attacking the army of small Cheerios, which are greater in number. Then you can decide who will win.’

‘How?’

‘Whichever gets eaten first wins,’ Ayush extemporizes.

They nod but lose interest after the first couple of mouthfuls.

‘Can I have sugar on mine, please?’ Sasha says.

‘No. Finish it without the sugar.’

‘May I have toast then?’ Masha demands.

‘Finish your cereal first.’

‘I don’t want cereal, I want toast.’ Sasha instantly piggybacks on the demand.

Ayush takes in the half-eaten banana, its peel already blackening, the blue bowls, with a painted yellow hedgehog, now drowned under milk and soggy cereal, in their centre, the small off-white puddle on the table, and suddenly remembers that his tea has been steeping for nearly fifteen minutes now. He removes the infuser, pours the tea from the pot into a mug so that it is half-full, tops it up with water from the kettle, then microwaves it for thirty seconds, watching the timer-clock count down from 00:30 to 00:00. There are five beeps. He takes it out, stirs, pours in a splash of milk, stirs briefly again, then says, very slowly and clearly, ‘What would you like your toast with?’

‘Egg, egg,’ says Masha. ‘I want toast soldiers to dip into the yellow of the egg.’

‘Jam,’ says the boy.

Ayush waits for one of them to change her or his mind. ‘Are you sure, both of you?’

They nod.

‘I’ll give you two more minutes in case you want to change your mind, OK?’ His breathing is even.