5,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

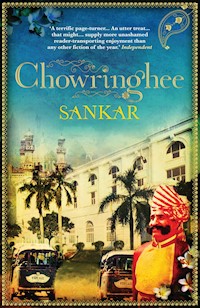

SHORTLISTED FOR INDEPENDENT FOREIGN FICTION PRIZE, 2010 Winner of the Vodafone Crossword Book Award, 2007 'A terrific page-turner... An utter treat... Chowringhee might, to many eyes, supply more unashamed reader-transporting enjoyment than any other fiction of the year.' -- Boyd Tonkin, Independent Welcome to the Shahjahan, one of Calcutta's oldest and most venerable hotels. Meet its newest receptionist and hear of the people who spend their days and nights behind the Shahjahan's grand façade, a world where greed, seduction and death coexist with love, luxury and pride. Chowringhee reveals an irresistible vision of a lost - and loved - metropolis, an homage to an old India of myth and memory. 'Chowringhee is one of those novels you don't want to end. It teems with life, creating an entirely absorbing world.' -- Vikas Swarup, author of Slumdog Millionaire

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2010

Ähnliche

Chowringhee

Sankar — the pen-name of Mani Sankar Mukherji — is one of Bengal’s most widely read modern novelists. Two of his novels, Seemabaddha (Company Limited) and Jana Aranya (The Middleman) were filmed by Satyajit Ray. He lives in Kolkata (Calcutta).

To Sri Shankariprasad Basu, the producer,director and composer of my literary life

____________________________

First published in Bengali as Chowringhee

by Dey’s Publishing in India in 1962.

First published in English

by Penguin Books India in 2007.

First published in Great Britain in hardback in 2009

by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2010 by Atlantic Books.

Copyright © Mani Shankar Mukherji, 1962, 2007

Translation copyright © Dey’s Publishing, 2007

The moral right of Mani Shankar Mukherji to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

The moral right of Arunava Sinha to be identified as the translator of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination and not to be construed as real. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 978 1 84887 762 7

Printed in Great Britain by

Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

Atlantic Books

An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd

Ormond House

26—27 Boswell Street

London WC1N3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

ONE

They call it Esplanade; we call it Chowringhee. And Curzon Park in Chowringhee is where I stopped to rest when my body, weary of the day’s toils, refused to take another step. Bengal has heaped many curses upon Lord Curzon – it seems that the history of our misfortunes began the day the idea of dividing this green, fertile land of ours into two occurred to him. But that was a long time ago, and now, standing in the heart of Calcutta on a sun-battered May afternoon in the twentieth century, I saluted the English lord, much maligned by history. May his soul rest in peace. I also saluted Rai Hariram Goenka Bahadur, KT, CIE, at whose feet were inscribed the words ‘Born June 3, 1862. Died February 28, 1935’.

You might remember me as the wide-eyed adolescent from the small neighbourhood of Kashundia who had, years ago, crossed the Ganga on the steamer Amba from Ramkeshtopur Ghat to gape at the High Court. That teenager had not only secured a job with a British barrister, but had also gained the affection of older colleagues like Chhoka-da. Basking in the love showered upon him by judge, barrister and client alike, he had revelled in the role of the babu, the lawyer’s clerk, soaking up with wonderstruck eyes the beauty of a new world.

In the midst of the desert of poverty and penury that had been my lot till then, the kindness and benevolence of my English employer was like an oasis, helping me to forget the past, leading me to believe that this would last forever. However, with the ever-alert auditor of this world always on the prowl for mistakes, mine, too, were discovered. The Englishman died. For the wretched of the world like us, the slightest storm is enough to destroy the oasis. ‘Move again, onward march!’ was the order from the cruel commander of victorious Providence to the vanquished prisoner. Reluctantly, I hitched my battered and bruised mind to the exhausted wagon of the body and started my journey afresh.

Onward, onward! Don’t look back.

I had only the road behind and in front. It was as if my tired and weary soul had found an unknown inn on Old Post Office Street for the night. With the first light of dawn, it was time to hit the road again. My fellow clerks at the high court shed tears for me. ‘To lose one’s job at such a young and tender age!’ Chhoka-da said. I hadn’t cried, though – not one drop. The bolt from the blue had dried my tears.

Chhoka-da made me sit next to him and treated me to a cup of tea. ‘I understand,’ he said. ‘I understand everything, but this cursed stomach doesn’t. You’d better eat something.’

That was my last cup of tea on Old Post Office Street. Of course, Chhoka-da tried to comfort me, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll get another job, here among us. Which barrister wouldn’t want a babu like you? It’s just that when you already have a wife, getting another one…they all have babus already.’

It isn’t like me to force my way into a conversation, but that day I butted in, ‘I can’t, Chhoka-da. Even if I get a job I can’t stay in this neighbourhood.’

Chhoka-da, Arjun-da, Haru-da – all of them were overwhelmed by my grief. A despondent Chhoka-da said, ‘We couldn’t do it but if anyone can, it’s you. Get out while you can – we’ll have the satisfaction of knowing that at least one of us has managed to escape from this wretched maze.’

*

Bidding them farewell, I slung my bag, complete with lunch box, over my shoulder and set out. The melancholy sun in the western sky set before my eyes that day.

But then…what next? Did I have the slightest notion that life could be so ruthless, the world such a difficult place to live in, its people so cruel?

A job. I needed a job to live like a human being. But where were the jobs?

Matriculation certificate in hand, I looked up people I knew. They were sympathetic, even told me how devastated they were at the news of the sudden disaster, but they blanched at the mention of a job. Times were bad, the company’s financial situation wasn’t very bright. Of course, they’d let me know if there was a vacancy.

I went to another office. Mr Dutta from that company had once turned to me for help when he was in trouble. It was at my request that our firm had taken up his case gratis. But now he refused to see me – the bearer returned with a slip of paper. Mr Dutta was very busy and had scribbled his regret at not being able to see me, adding that, much as he would have liked to, he would be too busy over the next few weeks to enjoy the pleasure of my company. The bearer asked me to write a note. Swallowing my pride, I did. Needless to say, there was no reply.

I sent applications by the dozen. I wrote with details of my qualifications to people known and unknown, even to box numbers. They served no purpose other than increasing the revenue of the post office.

I was exhausted. I’d never saved for a rainy day, and whatever I had was nearly spent. Starvation stared me in the face. O God! Is this what was ordained for the last babu of the last English barrister of Calcutta High Court?

Eventually, I got a job – as a peddler. Or, to put it more elegantly, a salesman’s job. I would have to go from office to office selling wastepaper baskets. The company’s name, Magpil & Clerk, had echoes of Burmah Shell, Jardin Henderson or Andrew Yule. But the man at the helm of it all, Mr M.G. Pillai, a young fellow from Madras, had nothing besides two pairs of trousers and a tie – a grubby one at that. One dingy room in Chhatawala Lane served as his factory, office, showroom, kitchen and bedroom. M.G. Pillai had metamorphosed into Magpil. And Mr Clerk? None other than Magpil’s clerk!

The baskets were to be sold to various companies and I would get four annas as commission for each one sold. It sounded like heaven!

But I couldn’t sell even those. Baskets in hand, I did the rounds of various offices, peering beneath the babus’ tables. Many of them asked suspiciously, ‘What are you looking at?’

‘Your wastepaper basket, sir,’ I’d reply.

How elated I was if it looked shabby. I’d say, ‘Your basket’s in a bad way, sir, why don’t you get a new one? Look, excellent product – guaranteed to last ten years.’

One day, the head clerk in an office glanced at the basket under his table and said, ‘Seems fine to me. It’ll last another year easily.’

I looked at him mournfully, but he couldn’t read my thoughts. I felt like screaming, ‘Maybe the basket will last another year but what about me? I won’t last another day!’ But in this strange city of Job Charnock, you can’t say something just because you want to. So I left silently.

I even met Westernized Bengalis in suits and ties. Tapping his elegantly shod foot, one of them said, ‘Very good. It’s very heartening that young Bengalis are going into business.’

‘Shall I give you a few, sir?’ I asked.

Pat came the reply, ‘Six, but don’t forget my share.’

Selling six baskets meant a commission of one-and-a-half rupees. Clutching the sales proceeds in my hand, I said, ‘This is what I make from six baskets, take whatever you think fit.’

Puffing at his cigarette, he said, ‘I could have easily got thirty per cent from someone else, but since you’re a Bengali, I’ll settle for twenty-five,’ and then proceeded to take the entire amount, after which he mourned the fact that our race possessed no semblance of honesty. ‘You’ve become quite a pro, claiming you don’t make more than one-and-a-half rupees from six baskets. Think we’re wet behind the ears?’

Too nonplussed to say anything, I left silently, wondering again at this strange world.

Amazing! Wasn’t it the same world where I had once discovered beauty, respected people, even believed that God is to be found in man? Now I felt like an ass. Not even life’s blows had bestowed wisdom upon me – would I never learn? This wouldn’t do. I had to become cannier. And I did. I raised the price of a basket from one rupee to one-and-a-quarter, and unhesitatingly gave away one anna to any buyer who demanded his cut. I would even keep a straight face as I said, ‘I make nothing out of it, sir, it’s a very competitive market. I’m selling without a margin to survive.’

I felt no qualms about the fact that I lied. All I knew was that I was alone in this self-seeking world and the only way I could make my way here was through ingenuity and cunning. I knew I would never be an honoured guest in any of life’s joyous festivals. So I had to gatecrash. It was then that I visited this office in Dalhousie Square.

It was the month of May. Even the asphalt on the streets seemed to be melting. The afternoon thoroughfares, as deserted as at midnight, shimmered in the light of a raging sun. Only a few unfortunate souls like me were on the move. They couldn’t afford to stop – they had to keep moving, hoping to run into luck somewhere.

My shirt was drenched with perspiration, as though I’d just taken a dip at Laldighi, and I was parched. There were arrangements by the roadside for even horses to drink water, but not for us. Oh well, the Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals was not responsible for preventing cruelty to the unemployed, so they could hardly be blamed.

Spotting a large building, I walked in. There was a lift inside. I stepped in, panting. No sooner had the liftman shut the gates than he noticed two wastepaper baskets in my hand. One look at my face told the experienced fellow who I was. He threw the shutters open and contemptuously pointed to the stairs, informing me for good measure, ‘This lift is only for officers and clerks. The company doesn’t pay me to service nawab-bahadurs like you.’

Indeed, why should there be lifts for humble hawkers like us? For us there was the spiral staircase. So climb my way up I did, without complaining – not even to fate. This was the way the world worked. Not everyone gets a lift to move up.

It had been a bad day. I hadn’t sold a thing, but had spent three annas already: one on tram fare, another on a plate of alu-kabli, and then, no longer able to resist the temptation, in utter recklessness, one on phuchka. I knew I had done something grievously wrong, squandering one anna on a moment’s weakness.

Entering the office, I peered beneath the tables and spotted baskets under each of them. A middle-aged lady seated at a desk near the door asked in an irritated tone, ‘What is it?’

‘Wastepaper baskets,’ I said in English. ‘Very good madam, very strong, and very, very durable.’

But the sales pitch didn’t help. She waved me away and I stumbled out of the room on my tired feet.

On a bench near the entrance sat a doorman with a huge moustache and an enormous turban, chewing tobacco. He was dressed in a white uniform, the company’s name glittering on a breastplate.

He stopped me and asked how much I made from every basket I sold.

I realized he was interested. ‘Four annas,’ I replied.

He asked how much a basket cost. I wasn’t a fool any more. I answered without batting an eyelid, ‘A rupee and a quarter.’

As he examined the basket closely, I spotted an opening and said, ‘Very good stuff, buy one and you can relax for ten years.’

Basket in hand, he walked into the office. The lady looked up, ‘I said we don’t want any.’ But the doorman wouldn’t take no for an answer. ‘Mr Ghosh doesn’t have one,’ he told her, ‘and Mr Mitra’s is broken, and the manager’s basket too is coming apart. We need to keep a few in stock.’

Eventually, the lady relented. I got an order for six baskets at one go.

I practically flew back to Chhatawala Lane. Tying six baskets together, I returned to the office. The doorman smiled at me.

Sending the baskets to the storeroom, the lady said, ‘Can’t pay you today. Have to draw up a bill.’

On my way out, the doorman grabbed me. ‘Got paid?’

He probably thought I was about to make off without giving him his cut. ‘Not today,’ I said.

‘Why?’ Rising again, he went straight to the lady’s table. His words revealed years of experience. ‘He’s a poor man, madam, has to do the rounds of many offices.’

A little later I was summoned. ‘Your payment’s been cleared,’ he told me triumphantly and, pushing a voucher across, asked if I could sign – if not, a thumb impression would do.

Seeing my signature, he laughed, ‘My god, you actually signed in English!’

Money in hand, I came out. I knew enough of such doormen – I would now have to share the commission, but this time I had already taken that into account.

When he looked at me, I was ready, and held out one-and-a-half rupees. ‘This is my commission. Whatever you want…’

I hadn’t bargained for his reaction. He paled visibly, as if all the blood had drained from his face. I still remember how his tall upright figure shook, and the genial expression was wiped off his face. I thought perhaps he was not satisfied with the share. I was about to add, ‘I swear I don’t make more than one-and-a-half rupees on six baskets.’ But I was wrong. I had misunderstood him completely.

Before I could respond he thundered, ‘How dare you? I felt bad for you…you think I got them to buy your baskets so I could make something out of it! Ram Ram!’

I could not control my tears that day. All was not lost yet. The world was not devoid of all goodness, after all. Men like him still existed.

He made me sit down for a cup of tea. As we sipped our tea, he put his hand on my shoulder and said, ‘Don’t be disheartened, son. Have you heard of Sir Hariram Goenka, whose bronze statue stands before the governor’s house? He too had to struggle to survive. I can see the same fire in your eyes. One day you’ll be as great as he is.’

I looked at him, unable to hold back my tears.

Before I left, he said, ‘Remember that the one above always watches over us – stay honest and keep Him happy, don’t cheat Him.’

The memory of that day overwhelms me even now. On this long road of life I’ve seen much wealth and an endless parade of splendour. Fame, status, influence, happiness, property, affluence – these are no longer beyond my reach. I’ve even had the opportunity of coming in close contact with those who are revered by society, those who create history, those who strive to better humanity through education, science, art, literature. But the unknown doorman in that unknown office in Clive Building is still the guiding star in my firmament, an indelible part of my memory.

Bidding him goodbye, it occurred to me that though he had trusted me, I was nothing better than a liar and a thief. I had charged four annas extra for each basket. I had betrayed his trust. From Dalhousie I walked straight to Curzon Park in Chowringhee. Whether it is people without offices to go to but anxious to get there, or people without a refuge but most in need of it, everyone stops for a few moments’ rest at Curzon Park. Time seems to stop there – no hustle-bustle, no hurrying around, no anxiety; just a sense of calm. On the verdant grass, many vagrants slept peacefully under the shade of trees, while a pair of crows perched silently on Sir Hariram Goenka’s shoulder.

I silently thanked all those people whose generous donations had made Curzon Park possible, including Lord Curzon. And Sir Hariram Goenka? It seemed he was unhappy with me and had turned his face away. As I sat at his feet, my lips trembled. With folded hands I said respectfully, ‘Sir Hariram, forgive me, I am innocent. That foolish doorman saw shades of you in me, but believe me, I have no intention of insulting you.’

I have no idea how long I sat there. Suddenly, I realized that like a young clerk playing truant, even the sun had taken a look at the clock, shut his files, and gone home. I was the only soul sitting there.

What else could I do? I had nowhere to go.

‘Hello, sir!’ A voice startled me out of my reverie.

A man in trousers and a jacket, briefcase in hand, stood before me. The briefcase was unmistakable – it was Byron. If his sudden appearance had surprised me, he was just as astonished to see me dozing in the park. After all, he had always seen me in Old Post Office Street. ‘Babu!’ he exclaimed.

I haven’t yet forgotten our first meeting. I had been sitting in my chamber, typing away, when a man with a briefcase entered. His skin was the colour of mahogany, but it had a sheen – just like shoes after they have received the four-anna treatment from the shoeshine boys at Dharmatala.

‘Good morning,’ he had said, and promptly sat down without waiting for my permission, as though we were old friends. The first thing he did was to draw out of his pocket a pack of cigarettes, a brand which, even in those hard times, sold for seven paise a packet.

‘Try one,’ he said.

When I refused, he had laughed loudly. ‘Don’t like this brand, eh? Very faithful, can’t leave someone you’ve loved once!’

At first I had thought he was a salesman for that cigarette company, but just as I was about to tell him it was no use offering such pleasures to an ascetic, he spoke again. ‘Got a case?’

Case? It was we who accepted cases. Before I could reply, he said, ‘I’m available for any investigation, family or personal.’ After a pause, he added, ‘Any case, however complicated and mysterious, will be made as clear as daylight, as transparent as water.’

I shook my head. ‘I’m afraid we don’t have anything right now.’

He put on his hat and got up. ‘That’s all right, that’s all right. But no one can say when or where I might be needed. If not by you, perhaps by people you know.’

He handed me a card. It said: B.BYRON, YOUR FRIEND IN NEED. TELEPHONE:

There was no number. Just a blank space after the word TELEPHONE. ‘I don’t have a telephone as yet,’ he said. ‘But I’m bound to in the future, so I’ve left space for the number. I’ll get it. Eventually, I’ll get it all. Not just a telephone, but also a car and a house and a large office. You have no idea what a private detective can do if he puts his mind to it. He can earn more than the chief justice.’

Private detective! I’d only read about them. I must have devoured a thousand detective stories ever since I laid my eyes on the printed word. Had I applied the same sincerity and devotion to Jadab Chakraborty, K.P. Bose and Nesfield’s textbooks as I had to Byomkesh, Jayanta–Manik, Subrata–Kiriti, Blake–Smith and other famous detectives, I wouldn’t have been in such dire straits. But these detectives existed only in my fantasies. Never for a moment had I imagined that they could be physically present, roaming around in this mortal world – that too in this city of Calcutta.

With great awe and reverence I had requested Byron to sit, and enquired whether he would like some tea. He agreed readily, and drained his cup in a minute. As he stood up to leave, he said, ‘Don’t forget me.’

I felt rather depressed. Surely detectives didn’t have to go from door-to-door looking for cases! As far as I knew, it happened differently: The detective chats with his assistant over toast, omelette and a cup of tea in his south Calcutta residence, when the telephone starts ringing. A trifle irritated, he rises from his sofa to take the call. A voice, perhaps the daughter or widow of the slain raja-bahadur pleads with him, ‘You must take up the Shibgarh murder case. Don’t worry about fees, we’ll pay whatever you want.’

Or, on a rain-soaked June evening, when a deluge descends on Calcutta, when trams and buses stop plying, when there’s no way of stepping out, a stranger clad in a dripping black raincoat bursts into the detective’s drawing room. Placing a fat cheque on the table, he starts recounting the thrilling tale of his mysterious past. Unruffled, the detective emits a cloud of smoke from his Burma cigar and says, ‘You should have gone to the police.’ Whereupon the stranger jumps up, grabs the sleuth’s hand and begs him, ‘Don’t disappoint me, please.’

And look at Byron here. He was out himself, case-hunting!

With many unusual people frequenting the legal offices of Old Post Office Street, I had thought I’d be able to help him – and taking up a case on my request, Byron would solve the mystery and earn nationwide fame. ‘Keep in touch,’ I had said to him.

Byron did present his varnished countenance again at Temple Chambers. This time he was carrying some life insurance papers. I was worried at first, for, despite the short time I had been here, I’d been accosted by at least two dozen agents already. Looking at those papers out of the corner of my eye, I began planning a way out. He seemed to read my mind, though, for he sat down and said, ‘Don’t worry, I won’t try to sell you a policy.’

My face reddened in embarrassment. Without giving me a chance to answer, he said, ‘A detective has to be a chameleon. One of my disguises is as an insurance agent.’

I had ordered a cup of tea for him, which he’d drained, and left.

I’d felt rather sorry for him – I really would have loved to be of use. If only wishes were horses…But I couldn’t get hold of anything for him. I told Chhoka-da, ‘If you have an enquiry to be conducted, why don’t you give it to Byron?’

Chhoka-da said, ‘You don’t seem to be up to any good, young lad. Why are you rooting for that Anglo? Be very careful. Many a young man has gone to ruin under the influence of these Eliot Road types.’

I did not heed his advice. To Byron I’d said, ‘I feel bad. You take the trouble to visit me but I can’t find an assignment for you.’

He was an optimist, though, and had said, laughing, ‘You never can tell who can help whom – at least, not in our line of work.’

It was on the strength of this brief acquaintance that Byron stared at my tired form in Curzon Park. ‘Babu, what’s the matter?’

I kept looking at Sir Hariram’s statue without replying, but he didn’t give up. He took my hands instead, probably guessing what the problem was, and muttered, ‘This is very bad, very bad,’ he said.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Be a soldier. Everyone has to fight to survive in this unfriendly world. Fight to the finish.’

Finally, I looked at him closely. His fortunes seemed to have changed for the better. He was wearing a clean shirt and a pair of brightly polished shoes. He went on with a homily on the value of life. Maybe he thought I was contemplating suicide.

Now, unsolicited advice is something I have never been able to stomach. I retorted somewhat bitterly, ‘I am aware, Mr Byron, that on the branches of that tree overhanging the stone-hearted Hariram Goenka, KT, CIE, many a troubled soul has attained eternal peace. You must have seen it in the papers. But don’t worry, I’m not going to do anything like that.’

Paying no attention to my philosophical reply, he carried on, ‘Cheer up, it could have been much worse. We could have been much worse off.’

A hawker came by selling tea. Cutting short my protests, Byron asked for two cups, then pulling out his diary, he said, ‘That’s one cup repaid. Forty-two to go.’

Sipping his tea, he asked, ‘Do you have a clean suit?’

‘At home,’ I said.

He jumped with joy. ‘Then there’s nothing to worry about. It’s all God’s will – why else would I have run into you today?’

I had no idea what he was talking about. ‘You will,’ he said. ‘All in good time. Do you suppose that I had that woman from Shahjahan Hotel figured out right away?’ He stopped talking and looked at his watch. ‘How long will it take – for you to go home, put on your suit and come back here?’

‘Where do I have to go?’

‘All in good time. For now, just come back here, below Sir Hariram Goenka’s statue, in an hour. Ask questions later, hurry up now. Quick!’

Even now I marvel at how I got back from Chowringhee to Chowdhury Bagan that day. In my hurry I stepped on several toes in the bus. The passengers protested, but I was oblivious – I was even prepared to put up with a few blows and kicks.

By the time I had shaved, donned my one and only suit and returned to Curzon Park, it was 7.30. Night in Chowringhee had taken on the form of a temptress. In the blinding glare of neon lights, Curzon Park looked an altogether different place – unrecognizable from the Curzon Park of mid-afternoon. It was as though a perennially unemployed young man had suddenly got a thousand-rupee job and had taken his girlfriend out on a date.

I am not particularly fond of poetry, but some lines I’d read long ago came rushing back. It was the same Curzon Park that had inspired Samar Sen to write:

After ages of snowbound silence

The mountain desires to be May’s missing clouds.

So at spring in Curzon Park,

Silent like rain-drenched animals sit

Groups of arch-bodied heroes

Razor-sharp dreams in melting melancholy are dreamed

By groups of men in the Maidan from wasted homes

At the invitation of French cinema, at the hint of a phaeton

Clouds bloodied in a mining fire, sunset comes

I could feel that in my fresh suit I no longer looked like an unemployed wretch. As if to prove me right, a masseur came up to me and asked, ‘Massage, sir?’

When I said no and moved on, he sidled up even closer and muttered, ‘Girlfriend, sir? College girl, Punjabi, Bengali, Anglo-Indian…’ The list might have become longer, but by now I was running hastily to meet Byron. Maybe he had got tired of waiting and left, maybe I had lost a golden opportunity forever.

But no, he hadn’t gone away. He was sitting quietly at Sir Hariram’s feet, his dark frame merging into the night so that his white trousers and shirt seemed to be draped over a phantom.

Spotting me, he rose and said, ‘I must have smoked at least ten cigarettes since you left. And with each puff I couldn’t help thinking that all of this has turned out for the best – for you as well as for me.’

Leaving Curzon Park, we passed the statue of Sir Ashutosh to our left and walked along Central Avenue towards Shahjahan Hotel.

I was filled with gratitude for Byron. I hadn’t been able to help him at all during my days at Old Post Office Street; it suddenly struck me that I hadn’t even tried hard enough. I knew so many attorneys, after all – they would have found it difficult to turn down a request from the English barrister’s babu. But to keep my self-respect intact, I hadn’t asked anyone for a favour. And today Byron had become my benefactor.

‘That’s Shahjahan Hotel,’ he pointed out from a distance. ‘Your job’s guaranteed. Their manager can’t refuse me.’

I looked at the most famous of Calcutta’s hotels. Around twenty-five cars were parked in front of the gate, and there were more coming. Flaunting nine or ten decorations on his chest, the doorman stood proudly, occasionally advancing to the portico to open a car door. A lady in an evening dress stepped out daintily, a gentleman in a bow tie behind her. Contorting her painted lips like she was about to burp, she said, ‘Thank you.’ Her companion had materialized in front of her by now. He held out his hand and, taking it, she walked in. The doorman took the opportunity to click his boots and salute in military fashion. The couple’s heads also moved a little, like clockwork dolls, in response. Then the doorman spotted Byron and, with utmost humility, offered a double-sized salute.

Even to this day, I never cease to be amazed at the thoughts that went through my mind as I crossed the hallowed portals of that awe-inspiring hotel. Thanks to my previous employer, I had had the opportunity of seeing many a pleasure garden, a few hotels too. But Shahjahan Hotel – it was a class apart. It was incomparable. It wasn’t so much a building as a mini township. The width of the corridors would put many roads, streets and even avenues to shame.

I followed Byron into the lift, and then out of it, with not a little trepidation. The May evening seemed to have a touch of December about it. I no longer remember how many corners we turned, but I am certain I would never have found my way out of the labyrinth alone. Eventually, he stopped before a door.

The liveried bearer standing outside said, ‘Sir got back a short while ago from kitchen inspection, he’s had his bath and is resting now.’

Byron wasn’t put off. Running his fingers through his curly hair he smiled at me and told the bearer, ‘Tell him it’s Mr Byron.’

It worked like a charm. The bearer came out in no time and said, bowing low, ‘Come in, please.’

I wasn’t at all prepared to see the all-in-all of Shahjahan Hotel, Marco Polo, in the state he was in: a sleeveless vest and tiny red briefs tried in vain to cover the essentials of his manly body. Not that he was bothered by the lack of clothing – he looked as though he was lounging by the poolside.

Spotting me, though, he jumped out of the bed in alarm and, muttering ‘Excuse me, excuse me’, ran towards the wardrobe. He quickly took out a pair of shorts, put them on, slipped on a pair of sandals and turned towards me. There was a thick gold chain round his neck. It had a black locket with something inscribed on it. His left arm sported a huge tattoo and so did his hairy chest, part of it peering out from behind the vest.

I’d expected Byron to open the conversation, but it was the manager who spoke first. Pushing a tin of cigarettes towards us, he asked, ‘Any luck?’

Byron shook his head. ‘Not yet.’ He paused and added, ‘Calcutta’s a mysterious city, Mr Marco Polo. Much bigger than we think.’

The light in Marco Polo’s eyes died out. He said, ‘Not yet? Then when? When?’

Some other time, I’d have smelt something fishy in this exchange and become curious. But now I wasn’t interested. Even if all of Calcutta went to hell, I wouldn’t care – as long as it meant a job for me.

Byron read my mind and broached the subject. Introducing me, he said to Marco Polo, ‘You have to give him a job in your hotel, he’ll be very useful.’

Marco Polo gestured helplessly. ‘Impossible. I have rooms to let in my hotel but not one job – we’re overstaffed.’

I was prepared for this answer – I’d heard it many times before, and would have been surprised not to hear it once more.

But Byron didn’t give up. Twirling his keys around his finger, he said, ‘But I know you have a vacancy.’

‘Impossible,’ shouted the manager.

‘Nothing is impossible – there is an opening, you’ll hear about it tomorrow.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘I mean advance news – we get a lot of information beforehand. Your secretary Rosie…’

The manager was startled. ‘Rosie? But she’s upstairs.’

With the solemnity of all the detectives I had read about, Byron said, ‘Why don’t you find out? Check with your bearer whether the lady was in her room last night or not.’

Marco Polo still refused to believe Byron. ‘Impossible,’ he said, and shouted for bearer number 73.

Number 73 had been on duty the previous night, and was on again that evening. He had barely perched himself on his stool when the manager’s summons came. Certain that he had committed some blunder he came in, quaking in terror.

The manager asked in Hindi whether he had stayed up all of the previous night.

Number 73 said, ‘God is my witness, sahib, I was awake all night, didn’t shut my eyes even once.’

In reply to Marco Polo’s query, he admitted that room number 362 had been locked from the outside all night – he had seen the key on the board.

With a faint smile Byron said, ‘At precisely the same time last night, room number seventy-two of another hotel in Chowringhee was locked on the inside.’

‘What do you mean?’ asked Marco Polo apprehensively.

‘I mean that it wasn’t just Rosie who was in the room but someone else as well. And I know him rather well – a client’s husband. Of course, I am not supposed to know all this, but Mrs Banerjee hired me for a fee. I submitted my report today on how far he has gone. No hope, I told her. This evening your assistant and Banerjee have made off by train. The bird has flown. So you might just as well install this young man into that empty cage.’

The manager and I were both thunderstruck. Byron laughed loudly. ‘I was on my way to you with the news,’ he said, addressing Marco Polo, ‘when I met my friend here.’

After this Marco Polo couldn’t say no. But all the same he warned, ‘Rosie hasn’t quit; if she returns in a couple of days…’

‘Get rid of him then if you like,’ said Byron on my behalf.

The manager of Shahjahan Hotel agreed. And I got the job. It must have been written thus by the gods in the ledger of my fate.

TWO

I was reborn. The last clerk of the last English barrister of the Calcutta High Court was lost forever. He would no longer spend time chatting with other babus on Old Post Office Street, no longer listen to the tales of his clients’ joys and sorrows in his chamber. His relationship with the law had ended for good. And yet it gave him a sense of great relief. The cyclone-battered ship was returning from the violent seas to the safety of the harbour.

Early next morning, I bathed, put on my last pair of clean trousers and shirt, and left home. I could see the majestic yellow building of Shahjahan Hotel from afar. ‘Building’ isn’t the right word, ‘palace’ is more like it. And that too not one for small-time rulers. The Nizam or the Maharaja of Baroda could unhesitatingly take up residence here – their glory and grandeur would not be compromised in any way.

Even at that early hour, several cars were parked outside the hotel. Their number plates made it clear that their owners weren’t permanent residents of Calcutta. Many a car of many a make, built in various factories in England, Germany, Italy and America, represented cities as distant as Madras, Bombay and Delhi and also the states of Mayurbhanj and Dhenkanal. One could spend hours watching these cars. A close observation would reveal that the caste system operated even in the automobile society, with the doorman tailoring his salute to the lineage of the car. Resplendent in his well-starched military uniform with its array of medals glittering on his chest; his impressive moustache and the way he occasionally bowed to usher in a guest, the gatekeeper uncannily resembled the world-famous Maharaja of Air India. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone told me that this man was the inspiration for the artist who designed the logo.

From the gatekeeper’s salute as I approached the entrance I realized that he had mistaken me for a patron. My first sensation on setting foot inside the hotel was of walking on butter. It felt like I was sinking under my weight on a soft satin bed and was then being gently raised aloft by a loving, kind-hearted fairy. With the next step I sank again, and the fairy, without the slightest show of irritation, lifted me up again. It was as though two invisible but beautiful fairies were playing ping-pong with my body on a carpeted table. Unaware that the best carpets in the world had this quality, I was disconcerted for a moment or two.

I literally waltzed my way across to the other side of the carpet – to the area marked ‘Reception’. The gentleman standing behind the counter showed all the signs of fatigue resulting from a sleepless night. But as I approached, he snapped alert and, conjuring up a smile, wished me good morning.

I was a little flustered. Without returning the greeting, I introduced myself. ‘I’ve got a job here, I met the manager Mr Marco Polo last night. He asked me to report today. Can I meet him now?’

His expression changed in a trice. The formal politeness gave way to a warm, friendly smile. ‘Welcome! Welcome!’ he said. ‘The Orient’s oldest hotel welcomes its youngest staff member.’

I was tongue-tied with nervousness. He extended his right hand and said, ‘My name is Satyasundar Bose – at least, that’s what my father christened me. As luck would have it, I have now become Sata Bose.’

I must have been staring blankly at him for some time, for with an affectionate nudge he said, ‘You will tire of this accursed face soon. In the long run it may even nauseate you. You may even throw up every time you see it. Come round behind the counter, so that I can complete the coronation formalities of Shahjahan Hotel’s young prince.’

I said, ‘I should meet Mr Marco Polo and…’

‘No need,’ said Bose, ‘he briefed me last night. It’s time to rev up.’

‘Meaning?’

‘You know how cars refuel and rev up their engines, don’t you? You must do the same.’ I smiled at his manner of speech. He continued, ‘Have you heard of the AAB?

‘Automobile Association of Bengal?’

‘That’s right. They have two competitions – a speed test to see how fast one can drive and an endurance test to see how long one can drive. We have a combination of the two here – a speed-cum-endurance test. The management of Shahjahan wants to find out how quickly you can do how much work.’

The telephone next to him rang. He picked up the receiver and in an artificial Anglo-Indian accent said, ‘Good morning, Shahjahan Hotel reception. Just a minute, Mr and Mrs Satarawalla, yes, room number two thirty-two, you’re welcome…’

I couldn’t comprehend a word. Bose smiled at me and said, ‘For now, concentrate on listening, you’ll get the hang of it eventually. Just don’t let your memory rust…electroplate it and keep it shining. The rest will come to you automatically. Take room numbers, for example…it helps a lot to know every guest’s room number.’

I looked at the reception counter carefully. There were three chairs behind it, but it was the done thing to keep standing. The table behind it had a typewriter and, next to it, a few thick ledgers: the hotel registers. The pendulum of an old, large clock oscillated lazily on the wall, as though it had just woken up from a long slumber and was ruminating.

‘Come around inside,’ said Bose again.

My thoughts must have shown on my face, which was probably why he asked, ‘Unnerved already?’

Embarrassed, I shook my head. ‘No, of course not.’

He laughed, looked around warily and said in a conspiratorial whisper, ‘Wait till the hotel wakes up – you’ll be amazed.’

I went behind the counter. As the telephone rang again, Bose picked up the receiver with practiced ease and spoke in a soft and stylish voice, ‘Shahjahan reception.’ Hearing the speaker at the other end he laughed and said, ‘Yes, Sata here.’ The two perhaps exchanged some joke, as Bose guffawed loudly. He put the receiver down and said, ‘The steward will be here any minute. Try to “butter” him up a little and keep him in good humour.’

In a few minutes, I saw a huge figure approaching the reception, a veritable Mount Vesuvius. But despite his girth, the man’s gait reminded me of a feather drifting in the breeze. His complexion was a dark shade of burnt copper, his eyes a pair of flaming wicks. He charged at me like a bull. ‘So, you’re the chap who got rid of Rosie!’

Without giving me a chance to reply, he thrust his left wrist under my nose. Drawing my attention to his watch he said that breakfast would be ready in fifteen minutes, and since the breakfast cards hadn’t been prepared the previous night they had to be done immed iately. It was obvious from the way he spoke that he wasn’t an Englishman. In halting, European English he said, ‘Take down, take down quickly.’

Bose pushed a shorthand pad across and said softly, ‘Write it down.’

Without further ado the steward barked out a list of items. Strange words, some of which I had never heard before, assailed my ears: chilled pineapple juice, rice crisps, eggs – boiled, fried, poached, scrambled. The man stopped a while, gulped, and then continued yelling in the manner of reciting a multiplication table: omelette – prawn, cheese, tomato…and so on. Words came tumbling out of his mouth like gunfire as he came to a halt with ‘coffee’.

‘Jaldi, jaldi mangta,’ he said, without even looking at me, and disappeared without giving me a chance to ask anything.

I was nearly in tears, never having heard the names of all those strange dishes before. I hadn’t been able to take down even half of what he’d said.

‘Fifty breakfast cards have to be prepared immediately,’ said Bose.

Seeing my face, he tried to console me. ‘Never mind Jimmy – the fellow always behaves that way – grunts like an old boar all the time.’

‘I haven’t been able to write down the breakfast list,’ I told him piteously.

‘Don’t worry about that. I know Jimmy’s list by heart. I’ll call out the names and you can type them out slowly. Ever since I came to this hotel I’ve been seeing the same menu, and he still wants new cards every day. At first I used to feel scared too, but now it makes me laugh – so many exotic names and pronunciations. In a couple of days you’ll be able to tell from the steward’s face what the menu will be – the moment he says Salad Italienne, you will know that our Italian steward wants consommé froid en tasse and potage albion.’

A novice, I made a lot of spelling errors in typing out the menu that day. Eventually, Bose took over the task himself, while I walked out from behind the counter and looked around the building. Things were very quiet at this hour of the morning – Shahjahan Hotel was not fully awake yet. The kitchen and pantry, however, hummed with a suppressed excitement. The bearers were pouring milk into pots, arranging cups and saucers, polishing the cutlery.

Returning to the reception counter I found Bose typing furiously. Had we waited for me to type the cards, breakfast would not have been served before lunch. But Bose’s practised fingers waltzed through the French words with speed and dexterity. How old was he? I wondered. Not more than thirty-two, thirty-three surely. He had an athletic build – not an ounce of excess fat anywhere on his body. His well-ironed jacket and trousers and matching tie set off his figure very well.

‘You know French?’ I asked.

‘French!’ He made a face. ‘You couldn’t get a word of French out of me at gunpoint. Of course, I know the names of the dishes – but then, even our head cook, who can’t sign his name, knows those names by heart.’ Arranging the cards, he continued, ‘The English, so clever in so many ways, don’t know to cook – you won’t find the name of a single decent preparation in John Bull’s dictionary.’

My knowledge of occidental cooking was limited to ‘Keshto Café’, situated next to Ripon College. The chop and the cutlet – gastronomic delights in my student days – were almost synonymous with British civilization. I was also acquainted with another rare English dish – the mamlette. I now discovered that the English had no hand in the invention of the chop or the cutlet, and that the mamlette was really an omelette, for which there were so many recipes in continental cuisine that a thick tome titled The Dictionary of Omelettes had been published in English.

Earlier, every time I ate out with my old employer, I always attacked the food without worrying about its name. It was he who had told me about the honest and inquisitive gentleman who had vowed never to eat anything without knowing its ‘background story’, and had added in a grave tone that, as a result, the poor man had eventually died of starvation.

Dispatching the cards to the dining room, Bose said, ‘You must have heard of Henry VIII. His fat bearded face in the history textbook made me so angry that I cut out his picture with a blade and threw it away. Had I known then that he had dug our graves for us, I wouldn’t have stopped there. I’d have burnt it as well.’

‘Why?’ I asked, astonished.

‘Henry VIII was as fond of eating as he was of getting married,’ said Bose. ‘He once went to a duke’s house for dinner. The other guests at the table noticed that he kept glancing at a piece of paper on the table every now and then before going back to the food. The assembled lords and counts, earls and dukes were at a loss – it must be a very important document, they thought, for His Majesty to have to read it even during dinner. After the meal, though, the king left the piece of paper on the table and retired to the drawing room. The attendants crowded around the table – but alas, it carried no state secret, only the names of a few dishes – the ones they had just had. The host had put them down on a piece of paper and given it to the king. Everyone said, “What a wonderful idea! This way you don’t have to stuff yourself with the boring items and then regret it when something lip-smacking turns up. If you know in advance you can decide what to eat and what to avoid, which ones to take more of and which ones less.”’

Bose smiled and continued, ‘That was the beginning of the menu card. What was intended as a convenience for a king has become a source of endless trouble for us hotel employees. Type the breakfast, lunch and dinner menu cards every day, arrange for them to be displayed at every table, and after the meals send the cards back to the storeroom where they gather dust for about a year. Then, one day, the Salvation Army is sent for, and they lift all the old papers and carry them off in a lorry.’

Glancing at the clock, he said, ‘Here, at Shahjahan, we have divided time in a different way. We start our day here with bed tea. Then comes breakfast time. What the world calls noon is lunchtime for us. Afternoon teatime and dinnertime follow – and no, it doesn’t end there. The date on the calendar might change; we don’t, as you will see.’

The workload at the hotel counter increases right from breakfast. It leaves one with no time for idle chitchat. Some of the guests leave the comfort of their cosy rooms around this time and come down to relax in the lounge. As they file past the counter in ones and twos, there is a mechanical exchange of good mornings – a guest serves a perfunctory ‘good morning’ which Bose volleys back with the expertise of a professional tennis player: ‘Good morning, Mr Claybar!’ ‘Good Morning, madam, hope you slept well.’

‘Madam’ was an elderly American lady. Bose had obviously touched upon a raw nerve.

‘Sleep? My dear boy, I haven’t known sleep for eight years. At first I took pills, then injections – but nothing works now. That’s why I’ve come to the Orient. One has heard so much about miracle healing in this country.’

Bose was appropriately sympathetic. ‘That’s sad! With so many rogues and scoundrels in the world, why does God have to be so cruel to someone as good as you? But don’t worry, this illness is easily cured.’

The lady sighed. ‘I don’t believe I’ll be able to sleep again in this lifetime.’

‘God forbid! My aunt had the same problem, but she recovered.’

‘Really! What medicine did she take?’ The lady practically threw herself over the counter.

‘No medicines…simply prayers. My aunt used to say: There is no power greater than prayer. Prayer can move even mountains.’

The lady was impressed. Putting down her vanity bag and camera on the counter and adjusting the scarf on her head, she asked, ‘Does she have supernatural powers?’

Before Bose could reply, another gentleman came along and stood across the counter – a foreigner, good-looking, six feet tall, impressively built as if moulded in Dorman Long steel. Bose leaned towards him and said, ‘Good morning, doctor.’

Looking sharply from behind his glasses, the doctor returned the greeting and said gravely, ‘May I have ten rupees?’

‘Of course.’ Bose opened the cash box to his right, took out ten one-rupee notes and gave them to the doctor, who scribbled his signature with his left hand on a printed voucher form and left.

‘Who is he?’ whispered the lady.

‘Dr Sutherland,’ replied Bose. ‘He’s here representing the World Health Organization.’

The lady seemed upset. She said disapprovingly, ‘You people are mad, you make no effort whatsoever to rediscover your ancient medical sciences. These foreign doctors whom you worship like demigods and spend millions of dollars on can’t even make an ordinary American sleep. While the naked fakirs of this country can stay asleep a couple of hundred years if they want to.’

Caught in a bind, Bose opted for silence.

The lady continued, ‘I’m not interested in your Sutherland, I’m interested in your aunt. I want to meet the great lady; if necessary I’ll arrange for her to go on television. You have no idea how much the United States needs your aunt.’

Bose’s eyes misted over. He pulled out a handkerchief and wiped them.

The lady asked in consternation, ‘What is it? Have I said something to upset you?’

Still wiping his eyes, Bose answered, ‘No, no, it’s not your fault. How could you have known that I lost my aunt just two months ago?’

‘Please forgive me, Mr Bose, I’m awfully sorry – may your aunt’s soul rest in peace,’ said the mortified lady and left hurriedly in search of a taxi.

Bose’s sudden outburst had caught me unawares, too. I tried to console him, ‘No one lives forever, Mr Bose. My father used to say that all of us have to learn to live alone in this world.’

Bose began laughing, leaving me utterly bewildered. ‘I have no aunt,’ he said. ‘I made it all up. If I hadn’t killed my aunt quickly, that woman would have wasted another hour of my time, and there’s a lot of work piled up.’

I was speechless for a while. ‘You know the High Court on Old Post Office Street, near St John’s Church? That’s the right place for you,’ I told him when I had recovered. ‘With this sort of presence of mind you would have owned a car and a house by now.’

Bose seemed lost in thought. ‘House? Car?’ he mused almost to himself. ‘Never mind, you’re new, so we’ll leave you out if it.’ He might have said more, but a bearer came and informed him that the manager was downstairs on kitchen inspection.

Bose turned towards me. ‘Go and have a darshan of Mr Marco Polo’s beautiful face. You’ll have to set up home with him.’

‘What’s he like?’ I asked apprehensively.

‘What do you think?’

‘It’s a romantic name. I had no idea such names were still in vogue.’

‘Romantic indeed,’ said Bose. ‘His more famous namesake spent his last days in jail, let’s see where this one goes.’

‘Is that a possibility?’ I asked.

‘Oh no, I merely said that in passing. He’s very efficient, a perfect manager. You know what Omar Khayyam said, don’t you? “It’s difficult for a country to get a good prime minister, but it’s even more difficult to get a good hotel manager.” They are born, not made. Countries have been known to survive bad ministers but no hotel can survive a bad manager,’ Bose said, laughing.

‘He was the manager of the biggest hotel in Rangoon,’ he continued. ‘Used to earn twice as much as here. But some whim brought him to Calcutta. At first we thought he may have been running away from some trouble he had got into, but the steward of that hotel, who stayed with us for two days on his way back to France, said that the Rangoon hotel was still sending requests to Marco Polo to go back.’

‘Why hasn’t the floor been cleaned? Even a pigsty is cleaner than this,’ screamed the manager, standing in the middle of the kitchen.

The head cook and an assistant were scurrying about the room, while Marco Polo scoured the corners for grime. He raised his head on hearing my footsteps. ‘Hello, so you’re here.’

I bade him good morning.

‘Learning the ropes, I hope?’ he asked.

The inquisition of the head cook was called to a halt, as the manager set off with me towards his office.

It was a small room, sparsely furnished. Three chairs were arranged around a table. On one side of the table was a pile of files, on another a typewriter. Two steel cupboards stood in a corner. There was a door in the wall to the right, which probably connected the office to Marco Polo’s bedroom.

He sat down and lit a cigar – a tall, manly figure, a trifle overweight for his age. He was balding a little as well, but because his hair was close-cropped, the bald patch didn’t show too much. The cigar made the grave face look even more so – he could have easily played Churchill onstage.

Preparing to dictate letters, he looked at me and said sadly, ‘Such a good girl – I’ll never find another Rosie. I had nothing to worry about in the office thanks to her. She typed my letters whenever I asked her to – even at midnight. There are some letters we get that can’t be left unanswered, they have to be replied to immediately.’

He went on to dictate a couple of letters. The language wasn’t very polished, but humility dripped from every line. It was obvious he kept detailed tabs on what wines were available. Having imported some liquor recently, he proudly dictated a circular: ‘We’re the only ones in India to import this world-famous liquor.’

Dictation over, Marco Polo left. Evidently he had a lot of other work pending. It is easier to rule over a small kingdom than manage a large hotel. Two hundred guests could give rise to two hundred problems a minute. The manager has to solve them all personally.

Typing letters was not something I was unused to, so it didn’t take much time. Sending them to the manager’s room for him to sign, I started sorting the papers. Though I owed my job to her departure, Rosie had left me in the lurch by running away suddenly – I had no idea where things were. I couldn’t even find a list. Trusting only my eyes and hands I started rearranging the mountains of files.

Opening the left-hand drawer of the table, I discovered some of Rosie’s personal effects – a bottle of nail polish, new blades and a small mirror. I felt depressed. Why was I even bothering to set things in order here? The much-loved young lady might reappear tomorrow, and then I would have to go back to Curzon Park. What was the use of putting down roots for just a couple of days?

Immersed in my work, I did not realize how the day wore away – I didn’t even realize that the hands of the clock had crossed the breakfast and lunch hours and were approaching teatime.

‘You’ve been working all day, sir, don’t you want a cup of tea?’

I raised my head and saw the manager’s bearer. He smiled pleasantly at me. He was getting on in years, his hair had turned grey, but he looked in good shape. ‘My name is Mathura Singh,’ he said.

‘Pleased to make your acquaintance, Mathura Singh.’

‘Shall I get some tea for you, sir?’ he asked.

‘Tea? Where will you get it from?’

‘Leave that to me, sir. They haven’t issued a slip for you yet, but once they do, you’ll have no problems about your meals.’

He brought the tea to the office, poured it, handed me the cup and said, ‘So this is where you’ve ended up, sir.’

‘You know who I am, Mathura?’ I asked, surprised.