Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

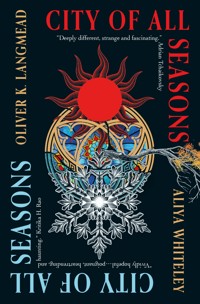

A vibrant and emotional science fantasy about cousins trapped in mirrored worlds – the resplendent and verdant summer city and the ice-carved wastes of the winter city. For fans of Every Heart a Doorway and This is How You Lose the Time War. "A beautifully strange and unique fable." The Guardian's Best SF of 2024 on Aliya Whiteley "A unique and memorable work." The Guardian's Best SF of 2024 on Oliver K. Langmead "An elegantly told meditation on how we can't leave ourselves behind." Esquire's 30 best SF Books of 2024 on Oliver K. Langmead Welcome to Jamie Pike's Fairharbour – a city stuck in perpetual winter, its windows and doorways bricked shut to keep out the freezing cold, its residents striving to survive in the arctic conditions. Welcome to Esther Pike's Fairharbour – a city stuck in constant summer, its walls crumbling in the heat, its oppressive sunlight a relentless presence. Winter and Summer alike, have both fallen under the yoke of oppressive powers, that have taken control after the cataclysm. But both Fairharbours were once a single, united city. And in certain places, at certain times, one side can catch a glimpse of the other. As Jamie and Esther find a way to communicate across the divide, they set out to solve the mystery of what split their city in two, and what, if anything, might repair their fractured worlds.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 428

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Cover

Praise for City of all Seasons

Also from Oliver K. Langmead and Titan Books

Title Page

Leave us a Review

Copyright

City of All Seasons

Jamie

Esther

Jamie

Esther

Jamie

Esther

Jamie

Esther

Jamie

Esther

Jamie

Esther

Jamie

Esther

Jamie

Esther

Acknowledgments

About the Authors

Praise for

CITY OF ALL SEASONS

“Deeply different, strange and fascinating - a study of hope against all odds of environment or society.” — AdrianTchaikovsky

“A moving ode to the power of creativity, and its ability to connect us as humans across space and time. It’s also a cleverly-painted portrait of a family whose creations divide as well as unite. Rich and imaginative, this novel brings together two of the best voices in modern speculative fiction. I loved it.” — LucyHolland

“An excellent read. A strange and atmospheric tale that immerses you so thoroughly you wake up in a different world altogether.” — T.L. Huchu

“Vividly hopeful while set within a frighteningly real post apocalyptic world, a poignant, heartrending, and haunting read of a family’s love and trauma, coloured with a mysterious enduring magic. This is a deeply humane work, a reminder of community and societal repair, that stayed with me long after I put it down.” — KritikaH. Rao

“A lyrical and kaleidoscopic novel reminiscent of both Piranesi and Gormenghast. The mysteries of summer and winter, love and loss, fiction and reality in this evolving landscape pulled me in and wouldn’t let go. As inventive as its cast of characters, City of All Seasons will stay with me for a long time.” — ElizaChan

“A lush and dazzling fantasy. A story full of wonder and magic, about family, hope, and fighting to repair what’s been broken.” — A.C. Wise

“A masterclass in dual worldbuilding … Whatever the season, the warmth of Whiteley’s and Langmead’s characters stand out.” — TimMajor

“Dreamy and tender … The worldbuilding is an endless delight! Perfect for fans of the Letters of Enchantment duology and a Darker Shade of Magic trilogy.” — JuliaVee

“Elegantly woven and alive with fascinating characters … Aliya Whiteley and Oliver K. Langmead have long since earned their reputations for inventive fiction; writing together, they might well be unstoppable.” — M.T. Hill

Also from Oliver K. Langmead

and Titan Books

CALYPSO

BIRDS OF PARADISE

GLITTERATI

Also from Aliya Whiteley

and Titan Books

FROM THE NECK UP AND OTHER STORIES

SKEIN ISLAND

THE ARRIVAL OF MISSIVES

THE BEAUTY

THE LOOSENING SKIN

LEAVE US A REVIEW

We hope you enjoy this book – if you did we would really appreciate it if you can write a short review. Your ratings really make a difference for the authors, helping the books you love reach more people.

You can rate this book, or leave a short review here:

Amazon.com,

Amazon.co.uk,

Goodreads,

Barnes & Noble,

Waterstones,

or your preferred retailer.

City of All Seasons

Print edition ISBN: 9781835411445

E-book edition ISBN: 9781835411452

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Street, London SE1 0UP

www.titanbooks.com

First edition: April 2025

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This is a work of fiction. All of the characters, organizations, and events portrayed in this novel are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

© Oliver K. Langmead & Aliya Whiteley 2025.

Oliver K. Langmead & Aliya Whiteley assert the moral right to be identified as the authors of this work.

Chapter headers and interior illustrations © Darren Kerrigan.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library.

EU RP

eucomply OÜ Pärnu mnt 139b-14 11317

Tallinn, Estonia

+3375690241

Typeset in Joanna MT.

One of my favourite movies is called Moon Voyage. The reel I have is so old that it’s sometimes difficult to see the actors through the artefacts, but I like it that way. The distortion gives the recording more distance, as if the movie really was filmed on the moon.

The film is silent, and the astronauts sit quietly in their rocket, communicating using hand signals. When they arrive on the moon they go out and explore in big, bulky suits, and they don’t find much, but that’s not really the point. What makes the movie special is their gentle, meticulous curiosity. They overturn moon rocks, and dig samples, and take pictures of craters. Near the end of the movie, the reel becomes so distorted that the astronauts become shadows; the artefacts are a blizzard that consumes them. We never find out if they make it home again, and sometimes, on clear nights, I study the moon and think about them.

Tonight, the sky is not clear. Tonight, the snow is so thick that I feel as if I too am in an old distorted black-and-white movie. Flakes fall like artefacts, blanketing everything, and I have to stride like a lunar explorer, bundled up in my thickest coat, with old tennis racquets strapped to my feet. Henry is with me, and he is dressed from head to toe in black wools and leathers – the uniform of the city’s authority – making him look like a silhouette against the white of the street. He uses a ski pole to keep himself balanced, and there is a rifle strapped across his back.

To anyone else, I’m sure that Henry would be intimidating. The uniform that he wears is designed to be intimidating. But he’s still my cousin: there is a slip of fair hair, protruding from beneath his hat, and his height makes his movements through the snow awkward, no matter how assured he pretends to be. He keeps having to adjust his rifle, which bumps his shoulder blades.

“You need warmer clothes,” he tells me, his mask muffling his voice.

I am wearing so many layers of tough, worn clothing, but he’s right. The cold is getting in, and I have to keep my hands in my armpits for warmth.

The silence is profound – there is nothing quieter than falling snow – and even the crunch of our slow progress feels distant. Tonight, my cousin and I are astronaut explorers together.

There are not very many working streetlamps left in Fairharbour, and we pause at each one. The drifts are high enough that if I stretch out I can press my gloves against the glass and feel the warmth of the bulb. I keep an eye out for anyone else, but we are alone. Anyone with any sense will be bundled up at home.

The streets are so close together in the cathedral district that there’s a little more cover from the elements, but the going is still slow all the way to our first stop of the night: the Shining Heart Cathedral itself. Tremendous icicles hang from its recesses, and its spire is completely obscured by the low sky. We shelter in the doorway of a crypt and peer up at the shattered stained-glass windows, where there should be colour but there is none.

“What do you need from here?” asks Henry.

“A bit of glass.”

“You can get glass anywhere.”

“You have no imagination.”

Henry’s brought a heavy white-bulb torch, and he lights it as we venture up to the wall of the cathedral.

I dig with my hands where the snow is shallow, and Henry aims his torch to help. The cold stings, even through my gloves, and I think about the gloves of the astronauts in Moon Voyage, which are so thick and insulated that they don’t give the actors much grip. They handle their tools clumsily, but I imagine that their hands must be warm.

Then, suddenly: colour. It’s so vivid that it feels as if I’ve fallen into a different movie. Technicolor, beneath the snow! These are shards of stained glass, fallen from the cathedral’s window – blue and red and yellow – and I gather the smallest pieces with the same reverence I would use for sapphires and rubies. When I have enough, I pack them away, and the world is black-and-white once more.

There’s a bit, later on in Moon Voyage, where one of the astronauts gets separated and wanders the desolate moonscape all by himself, and I think about that scene as we head deeper into the city. I am glad Henry is with me, tonight, even if we don’t talk much anymore.

* * *

I think, to understand Fairharbour – the way Fairharbour is today – you first have to understand the weatherbomb. When the weatherbomb struck, not long after my tenth birthday, it killed nearly everyone in the city.

We were taught about weatherbombs in school, back when they were just used as an agricultural tool. Need rain to water your crops? Need sun to dry the ground? Need a cold snap to help your raspberry bushes grow? Set off a weatherbomb and fix the weather the way you want. There’s an odd history when it comes to using weaponised terms in agriculture – seed bombing, rain guns and the like – but in this case, the name turned out to be a portent.

At school, we were also taught about the wider world, and all the nations in it, quarrelling in the way that nations do. It’s an odd thing, learning about war as a child, because it feels so benign. You learn about war before you really understand what death is, so it feels more like a playground game. I remember playing at war with my cousins: shooting at each other with finger-pistols, and crossing sticks as swords. Henry was always the best at it. Anyway – the point I’m trying to make is that the precise politics of it all never really sunk in for me. I understood that there was a big wide world beyond Fairharbour, where nations warred with each other, but they were never really more than places on the classroom globe. I understood that our island city was part of a bigger country, and that that country was on unfriendly terms with some other countries, but, of course, I had never left Fairharbour. The mainland, and all those other countries, were no more than fictional places I saw on the TV and at the cinema. When the weatherbomb struck, none of those places seemed to matter; they were still unreal. I couldn’t tell you who dropped the weatherbomb on Fairharbour, or why. I only know that it killed most of my family.

It was a winter weatherbomb. The blizzards shattered windows, and buried the city so deep in snow that we mostly live on the upper floors of our homes. It froze the surface of the sea into terrible icy shards, trapping us here. The phone-lines went down, and we could no longer receive any radio signals. We became entombed in our winter city. Even when those first blizzards dissipated, and we emerged into the cold light of the winter sun, we could no longer see the mainland; cut off by a haze of storm clouds that have never lifted.

Sometimes, people leave the island, but nobody ever returns, and nobody from the mainland has ever come to rescue us.

We were taught that most weatherbombs dissipate after a week at most, but it has been eight years and Fairharbour remains resolutely wintery; the temperature has never risen, and the frozen sea has never melted. Some of the island city’s brightest remaining minds occasionally scribble down sums and shake their heads at the yield of the weapon that must have been deployed. They cast their eyes to the sky, in search of a spring that never comes.

The rest of us grieve, each in our own way, for those we lost.

* * *

One of the people I miss the most is my grandmother, who was a famous film director.

Grandma Pike’s first Technicolor movie was a short film called Lavender. It’s one of my favourite movies because it was filmed a couple of decades before I was born, when Technicolor was first being introduced, and there is something indulgent about the way it focused on colour. There isn’t really a plot to Lavender – it feels more like my grandmother taking the time to experiment with the Technicolor format before doing anything more ambitious with it – but it is certainly a love letter to its subject matter: Fairharbour’s very own Lavender Theatre.

The film opens with a shot of Magnolia Court, just outside the box office. It’s spring, and the magnolia trees are in bloom. There are close-ups of petals and flowers, and the branches move gently, jostled in the wind. Voices gradually become apparent, and the camera shifts from the trees to the people gathered beneath them. They are a diverse selection – young couples, elderly folk, and parents with their children, all queueing for tickets. The fashion at the time is floral, and everybody is illuminated by the sunshine.

Today, in my winter Fairharbour, almost forty years later, Magnolia Court is empty. The trees are all gone – cut down for fuel – and their stumps are buried beneath the snow. Henry scans the entrance with his torch. The city’s authority – the people who employ Henry – bricked the Lavender’s doors up years ago. If a building is no longer finding use, they seal it shut. They tell us that they are bricking shut the city to protect it from scavengers and the weather, ready for when spring arrives, but spring never arrives, and so much of the city has been sealed that I find myself crawling through more windows than doors these days.

We call them Doormen, the people Henry works for. It was a joke, to start with, but it seems to have stuck.

“Are you sure you want to go inside?” asks Henry. And this is the reason why he has come with me, tonight. The front entrance may be bricked shut, but there is a back way in, and he has the key. A Doorman always has keys.

“There’s something I need.”

Henry shivers. “You can go by yourself, then.”

“You don’t fancy it?”

“It looks like a tomb,” he says, and I think he’s right. These days, the Lavender Theatre is an opulent, windowless tomb. “I’ll let you take my torch, if you like.”

“Thanks, Henry.”

He shrugs and gives me the torch, along with the key. “Don’t be too long. I need to get that key back before anyone notices it’s gone.”

The truth is, I’m not sure why Henry is helping me. He’s meant to be keeping scavengers away from all the sealed up buildings or finding new sources of food and heat to hoard. The Doormen live well while the rest of us freeze. I eye up the rifle he carries, and wonder if he’s ever shot anyone for a tin of beans. Maybe it’s our family that makes tonight’s uneasy alliance possible. We are still Pikes, after all: Jamie Pike and Henry Pike, grandchildren of the great Carmen Pike herself.

In Grandma Pike’s film, the Lavender Theatre’s box office is busy. The vividly red carpet makes everyone look as if they are queueing up for a premiere. The staff are dressed formally, wearing white shirts and red waistcoats. Children carry pink whirls of candyfloss, and adults pluck from boxes of popcorn. There is a bar, and behind the bar are bottles of liquor in every colour. The camera idles on a couple sat at the counter, so focused on each other that they feel to us like the eye of the Technicolor storm.

Today, the box office is dark. The bar and confection stands were picked clean years ago, and the wallpaper hangs in ribbons from the walls. It’s warm in here. I remove my mask, hoping to catch a sweet scent on the air, but all I get is a stale mustiness. I cast Henry’s torch over the bar stools and try to figure out where the couple from the film were sat.

Over beside Screen One is a poster for Carmen Pike: A Retrospective. There is a list of her films on it, and I trace them with a finger. Her experimental early years; her big break, with her notorious musical; her heady blockbuster years, adapting famous novels into visual masterpieces; her return to Fairharbour, and final few local features. I think I’ve seen most of them, except for the last: the autobiography, Swimming Pikes!. I was deemed too young to attend the premiere.

In the film Lavender, Screen One is spectacular. The camera spends a while trained on the chandelier and its glittering crystals. The stalls are made from an ornately carved wood – part of the Lavender Theatre’s legacy as a live theatre, before it became a cinema – and we are treated to close-up shots of grotesques and gilded railings. The camera pans around, showing us the circle, the balcony, and the boxes, before coming to a halt above the orchestral pit. There is an enormous organ in the pit, and a member of staff sits at it, playing something jaunty for the audience as they filter in. Finally, when everyone is seated, the stage curtains part, and there is the screen itself: an enormous, empty white oblong.

Today, the screen is not white. There is a spray of blood across it.

The blood is old: eight years old. And it belongs to Carmen Pike. Because it was here, in her beloved Lavender Theatre, that she was murdered.

I keep Henry’s torch focused on the blood and consider it. I think about the relentless blizzards during the first days after the weatherbomb struck, keeping us all indoors. It was during one of those blizzards – or maybe just before them – that my grandmother was killed. We only found out about it weeks after the fact, once the city began to move from surviving to counting its dead, and the authorities – what few of them remained – could give us very little information. Her murder remains a mystery.

The chandelier has fallen, and I have to climb around it. I lower myself into the orchestral pit and appraise the organ, glad to see that it has been well preserved. The lead is slightly tarnished, but a bit of polish and it will gleam again. I take a wrench and remove some of the tubes. Then, I pause, and turn my torch back to the stage, in search of answers.

There are no answers to find, here. My grandmother’s body was removed shortly after she was found – only her blood remains.

In her film, Lavender, we never see what movie is showing in Screen One. The camera cuts away to the projection room. It is dark, and there are stacks of reels beside the bulky projector. The camera focuses on the light beaming from its lens, lingering, before cutting to black.

There are no credits at the end of Grandma Pike’s movie.

I stop in the projection room before I leave the Lavender, and sift through the reels that remain. Most of them are labelled, but a few are blank where a name should be, and I have to hold them up to the light so that I can see what’s on them. I find a couple of blockbusters, and one of my grandmother’s movies that I haven’t seen in years, and I put them away in my pack to enjoy later.

Outside, the snow is still falling, and Henry is exactly where I left him. He dusts the snow from his shoulders, and I return his torch and key.

“Find what you were looking for?”

“Yes and no.”

“Time to go, then.”

Henry turns his back on the Lavender, and so do I. We leave it together, in silence.

If you look carefully, there’s a shot about halfway through Lavender, in the box office, where the camera is visible in a mirror. Sometimes, I will pause the reel and see my grandmother there. She looks young, and she holds the camera with confidence, and I miss her with such an intensity that I can’t leave the film paused for very long. And sometimes, when I see her, I think about Esther, too. Our cousin Esther, who didn’t survive the weatherbomb. I wonder if she would have grown up to look like my grandmother. I wonder if she would been tall, and stern, and brilliant too.

* * *

I’ve only ever met one person completely unimpressed by the work of Carmen Pike, and that was Pawel. I first met Pawel the day that Aunt Fi’s radio broke.

Once a week, before the weatherbomb, I would be deposited with my cousin Esther and her mother, Aunt Fi. On rainy days we would bake together in Aunt Fi’s tiny kitchen – mixing and kneading and pouring, all while listening to her antique radio. The radio was made of wood, and had a big brass dial, and sometimes we had to spend a while delicately positioning and repositioning the aerials until it picked up a signal. Esther and I would dance to the latest hits, and Aunt Fi would hum along to the classics, and we’d all listen to the news solemnly together, all the way up until the day that the radio failed to pick up any signals at all. No matter how much we manoeuvred the aerials, all we got was static, and it was clear: the radio was broken.

Aunt Fi put her radio in a big plastic bag, and we put on our raincoats. We went out together into Fairharbour in search of repair. The first place we tried was the sleek modern radio and TV shop in the cathedral district. The man behind the counter tinkered while Esther and I ogled the colour televisions, mesmerised by the new technology. But eventually he shook his head: the radio was just too old, and he didn’t have the parts to fix it.

Next, we went to the record store, and the girl at the desk took a screwdriver to the radio while Esther and I flicked through the latest releases, delighted to see some of the songs we’d heard in Aunt Fi’s kitchen. No luck, though: the record store girl didn’t know what to do with it either. But she did recommend a shop a couple of streets over, called Radio City.

Radio City was fairly unassuming from the outside. It only had a small window, and it was at the end of a cobbled alleyway. It was starting to rain more heavily outside, so we all trooped in and dripped on the welcome mat, confronted by shelves upon shelves of wireless sets in various states of disrepair. Among them sat a broad-shouldered man with a thick beard, who spoke with a heavy accent and introduced himself as Pawel.

There was nothing to distract Esther and me, so we stood quietly and watched as this strange man, who we could barely understand, took apart Aunt Fi’s radio with a dexterity that defied his thick fingers. His tools were weathered, just like his hands, and he whistled a jaunty tune while he worked, and when he noticed us watching he turned the radio around and slowed down, revealing all the parts on the inside and explaining them to us one by one, showing us what was broken and how he was going to fix it.

We returned to Aunt Fi’s house in a daze, and went through the motions of baking some biscuits and listening to the radio. But when my father came to pick me up I was distracted. Part of me, I think, was still in Radio City, watching Pawel’s repairs.

Next week, Aunt Fi was delighted to report that the radio was broken again, and we three returned to the shop. Pawel was surprised, but got right down to work. Again, he showed us exactly how it needed to be repaired, and this time he let us use some of his tools, and we fixed it together. When, next week, the radio was broken for a third time, Pawel was less surprised. The week after that we brought him some biscuits, and Aunt Fi wore one of her nicest dresses, and a perfume so strong that it made my eyes water.

As weeks turned into months, we slowly learned more about him.

Pawel came to Fairharbour as a refugee midway through his life. He never told us much about the place he came from, but I’m pretty sure it had a lot of evergreen trees. There are very few evergreen trees in Fairharbour, and those few that remain were planted by Pawel, who arrived in the city with no more than his clothes and a bag full of pinecones. The first thing he did after he was given a small apartment in the shadow of Cherry Mount was to plant those seeds wherever he could find space – at the edges of parks, up among the hills, and even in his neighbour’s gardens. In the years that followed he took odd jobs and worked with borrowed tools, patiently nurturing his saplings until the trees grew tall enough that he could take branches from them without killing them. And with those branches, stripped of their firs, he whittled tools of his very own – the tools of his trade.

The radio business was what paid the bills, but the truth was that Pawel could repair just about anything. I saw him fix a bicycle that looked bent out of all proportion, revive an ancient, rusted lawnmower, and repair an outboard motor so tangled with seaweed that Radio City stank of the sea for days afterwards. He would even make some things from scratch. His speciality was tools – hammers, and saws, and screwdrivers – but every so often I saw him turn his creativity to something more precious, like a kite or a compass. And sometimes, on rare occasions, Pawel’s creativity gave an object an unexpected property. The bicycle he repaired was completely silent – it never rattled at all – and the kite would fly even when there was no wind, and I once saw him make a hammer that could strike the stone from a cherry with a single tap.

One of the best days of my life was when Aunt Fi and Pawel got married. Sunlight blazed in through the windows of the Shining Heart Cathedral, and after the vows had been exchanged we all went outside and threw handfuls of rice over the new couple, following them through the streets in a procession to the base of Cherry Mount.

Instead of taking the gondola, Pawel lifted Aunt Fi in his arms and carried her, one shaking step at a time, all the way to the summit. It was a tradition, he told me, breathless at the top: where I come from, a new groom must carry his bride all the way to the peak of the nearest mountain.

They are all gone, now. The weatherbomb took Pawel, and Esther, and Aunt Fi, and nearly all of my eccentric, feuding, beloved family from me. But I still have a workshop. And I still make things.

* * *

My own workshop is in the ruins of the Fairharbour Patent Office.

When I was eight, I dreamed about robbing the Patent Office. I was going through a phase of watching every wild west movie I could find, and I’d practice, with a handkerchief over my mouth and my fingers as guns, holding up saloons and banks. I thought that the Patent Office was the most bank-like building in Fairharbour, and every time I passed it by I’d imagine riding a horse in through the big double doors and firing a pistol into the air, forcing the bank manager to open the vault, or maybe blowing it open with a stick of dynamite. Then my horse and I would ride down the steps and away into the city, to hide from the sheriff and await the final showdown.

As it turns out, I was almost right about the Patent Office. It was a kind of bank, a bank to which people from all over the world would send their inventions to keep them safe. Today, it juts from the snow, an enormous, half-collapsed ruin of a building, and even though the big double doors have been bricked shut it’s easy to get inside because there are so many gaps in the masonry. Some of the windows are still intact, secured with reinforced glass and metal bars, but there’s no keeping me out.

I pause with Henry at a gap in the wall.

“Does anyone know I’m living here?” I ask him.

“I do.” I can’t figure out the tone of his response.

“Well.” I never know how to say goodbye to him. I should invite him inside, but I won’t, because I’m a bandit outlaw and he’s a sheriff’s deputy. “Thanks, Henry. For your help.”

He nods, and I can’t read his expression behind his mask. “Take care, Jamie. Give my best to Bea.” And with that, he vanishes into the snow, becoming a silhouette.

I wonder where he goes. He’s never invited me over to his home, which must be a cosy house. All the Doormen have cosy houses. I imagine a living room with ticking radiators, and a kitchen stocked with groceries, and maybe even a cat, demanding food. The Doormen have generators for when the city’s electricity goes down – as it regularly does – and I imagine them burning fuel to run VCR machines, lounging on sofas and sipping at hot chocolate. I imagine the coat stand by the front door, where Henry keeps his rifle.

I linger a few moments longer outside, feeling the cold. Then, I head in.

I think eight-year-old me would have been delighted to learn that I live in the vault.

The vault door features both an enormous wheel and gigantic metal bolts. We mostly just leave it ajar, and today is no exception. I slip through to the interior security office where we have our living room set up. The two-bar heater is on, which means that Bea is home, and I warm my hands on it before going to find her.

Bea tells me that the Fairharbour Patent Office is the only Patent Office in the world that has a vault. Usually, they’re a lot more stuffy – locked cabinets, and rows of numbered scroll-tubes. Fairharbour’s Patent Office vault was the result of a maverick architect insisting on literalising the idea that patents need to be protected. It was one of the reasons Bea moved to Fairharbour – to be in a place so full of creative minds that it could produce a place as peculiar as its bank-like Patent Office.

First, I knock on the door of Bea’s office. There’s no answer, which means she might be absorbed in something. Bea is the last of Fairharbour’s patent engineers, which makes her simultaneously one of the smartest people left in the city, and one of the most distractible. Her engineering expertise is so broad that she is not only able to understand most of the patents we share the vault with, but she is also one of the few people able to help when the power station goes down. That is, when she can be persuaded to leave her office.

I check a few other places anyway. She’s not in the archives, where thousands of scrolled-up patent blueprints are stored in little alcoves. She’s not in the cafeteria, where I find half a tin of peaches that I quickly finish off. And she’s not in our little cinema, either. I’m taken by surprise when I find Bea in my workshop. She’s hunched over a workbench, furiously scrubbing at something.

“What are you doing?”

Bea’s face is bright red. She is a small woman, and has heightened a stool to work at my bench. I have always loved the way that there is usually a smudge of something somewhere on Bea’s face. Before the weatherbomb, it would be a bit of eyeliner, or a fallen eyelash, but these days it is more likely to be ink. Right now, there is a smudge of grease on Bea’s chin. “You wanted wingmirrors, didn’t you?” She huffs. Wiping away at her work, she shows me a bright, mirrored surface. “There. Good as new.”

There are four wingmirrors in total, and they are hardly scratched at all.

“Where did you find these?”

“I went for a walk to the factory district. Still a few trucks parked up out there.”

“But they’re pristine!”

“They’re pristine because I’ve been polishing them all evening.” Bea wipes her hands on a rag. “How was the theatre?”

“Spooky. I got us some new films, though. Want to watch one later?”

“That sounds lovely. Did you find the parts you need?”

“I did.” I show her the shards of stained glass and the brass tubes.

“Well. Don’t let me stop you.” Bea shuffles out.

“Bea?”

“Yes, love?”

“Thank you!”

Bea is almost family, in an official sense. She dated my father for years, and there were so many times when I thought he would propose to her, but he never did. She seemed to keep him in a state of permanent uncertainty – so absorbed in her work at the Patent Office that he was never quite sure how serious their relationship was.

These days, official or not, she’s the best family I have left. I go to the hallway and watch her return to her office, humming a half-remembered theme tune from one of our favourite movies. We watch a lot of movies together. Or, rather, Bea sleeps while I watch them.

I shut the door to my workshop, take a deep breath, and get to work.

All of my tools are my own. A few years after the weatherbomb struck I returned to Radio City to see if I could salvage any of Pawel’s, but the place had been scavenged so thoroughly that there was nothing left. So, I did what he did. I went and found his evergreens, and cut down the branches they could spare, and whittled them into shape, one tool at a time, until I had enough to work with. I could have raided the hardware stores with everyone else, but it wouldn’t have been the same. I needed the right smells – the same as Pawel’s workshop.

Usually, I make trinkets and devices by following diagrams, so that I can trade them for food. In fact, I have been collecting parts for one particular patent, which Bea found for me a few days ago. When I open one of Pawel’s old pine oil mixtures, and the scent of it hits me, I am reminded of the days I spent in his workshop, learning how to make things with Esther, and I find that I don’t need the blueprint anymore. The device comes together so easily, a thing made of memories, and instinct, as much as craft.

By the time I am finished, Bea is asleep. Slumped over in the chair beside the two-bar heater, she looks her age: greying at the temples, crow’s feet at the corners of her eyes. Her old blue boiler suit is getting threadbare, too; I make a mental note to patch it at the elbows, before she wears right through them. I gently wake her and show her what I made with the stained glass, and brass tubes, and the wingmirrors she salvaged for me.

She holds it so delicately. “Is it a telescope?”

“It’s a kaleidoscope.”

None of its components are ideal. The tubes are not quite flush, letting in flickers of light, and the mirrors are uneven. The pieces of stained glass are still sharp, limiting its lifespan because they scratch the interior with each tumble, blurring it into gradual uselessness. But Bea holds it up to her eye, and turns the tubes, and cries out in delight at what she sees. “The colours!”

When she lowers it, she smiles warmly at me. “You make wonderful things, Jamie.”

“Should get us a few tins of food.”

Beatrice nods. “Someone will love this.”

I take it from her and wrap it carefully in cloth. “Want to watch a movie?”

“What time is it?”

“A few hours before dawn.”

“That sounds good.”

I help her to her feet, and we wander through to the vault’s own little cinema. A long time ago, when the vault was designed, its architect was thoughtful enough to install plush, comfortable sofas for those poor engineers forced to watch hours of dull technical patent footage on the cinema’s projector, and Bea settles into one while I sort out the movie. In the end, I decide to watch the one by Carmen Pike. From what I remember, it’s a silent ethnography of a small island nation that no longer exists, filmed during her earlier, experimental years, and though it is lengthy and meticulous there is something haunting about it. I must have last seen it when I was six – entranced by the idea that it was of my own famous grandmother’s making – but I still remember the smiles of the children in the footage, each entranced in turn by the camera being pointed at them.

By the time the reel starts spinning and the titles appear up on the screen, Bea has already fallen back to sleep. I shuffle into the comfortable chair beside her.

I watch my grandmother’s movie and consider her murder. It’s been so long that I doubt I will ever find out what happened. But I’ve always wondered if a member of my family might have been involved. For all the happy memories of weddings and parties, I have just as many of bitter, heated arguments.

The clicking of the projector is a comforting lull, and as I watch silent conversations exchanged between distant peoples long dead, I, too, drift away.

* * *

At dawn, I set off for Fairbright Fountain. It’s not far from the Patent Office – the centrepiece of a broad plaza. With sunrise, the snow has stopped falling and the air is calm enough that I can raise my goggles to see the blue sky properly, without the wind stinging my eyes.

This is where I go when I want to remember what summer was like.

The fountain is frozen. From the open mouths of its gargoyles and the urns of its cherubs spike jagged icicles, and the depths of its pool are white with snow. Once upon a time it was painted with gold leaf, and the remnants of that leaf still cling to the edges beneath the silvery ice, making the whole thing glimmer.

Before the weatherbomb, Aunt Fi would sometimes take me and Esther to the fountain to play. It was a strange choice given the city’s quay and beaches, but I think Fi liked the city noise: the calling of the pigeons; the footfalls of all the people passing through; the endless jugglers, and fire-eaters, and entertainers that would play for the crowds. And there, just beyond the plaza, was the Cathedral of the Shining Heart itself, visible from a bench she coveted. She would arrive early to get that bench and sit there with a novel while Esther and I chased the birds, watching as we splashed in the gold-leaf fountain. There were so many coins in the fountain – I remember the way they felt beneath my toes – but it was bad luck to take any because each was a wish.

It has been so long since the last summer in Fairharbour. Sometimes, spring shows up in the margins of the city, but it never lasts long: daisies beneath a post-box, or ripe pears at the base of a barren tree, or sharp, melting rain that washes a street free of ice for a day or two.

I have come to Fairbright Fountain to test my kaleidoscope, but I am filled with thoughts of distant summers – of a city that was green instead of white.

I raise the kaleidoscope to my eye. The tubes slide, and the stained-glass shards tumble, and the effect is everything I hoped it would be. I hear my own laughter as I make the fountain turn, reflected in all the mirrors of the mechanism, and like a vision, as if I have conjured it there, I see something alive and green in the depths.

I blink, trying to clear the memory from my vision, but what I am seeing remains. The edge of a vividly emerald leaf. The curl of a crisp stem. I lower the kaleidoscope and study the plaza, but there is nothing green for it to reflect, and there are no green pieces of stained glass inside it.

I turn in place with the device to my eye, sliding the tubes and aiming it in a wide arc. There is white and white and white, but sometimes, at the edge of the mirrors, is something green again. The more I turn, the more glimpses I am given until, at last, I see what I think might be a person. I only catch the very edge of a sleeve, a small patch of heavily tanned skin, but it’s unmistakable – the kaleidoscope has shown me someone wearing a ragged T-shirt.

I spend the better part of an hour turning the mechanism and building up a picture from the snatches I am given. I was wrong to think I was glimpsing a memory. The city I can see in the kaleidoscope is overgrown in a way that the city I knew from before the weatherbomb never was, and only Fairbright Fountain itself is familiar. There is shimmering water, and it remains vividly, vibrantly gold, reflecting the fierce fiery glow of a hot sun. I train the kaleidoscope on the cathedral and its spire, which here has been rendered crooked by years of snowfall, and in the mirrors it has a tree growing from it. A tall, robust growth in the full bloom of a season I barely remember.

The kaleidoscope is showing me Fairharbour, but not my Fairharbour.

It is showing me a summer version of my city.

* * *

There are plenty of mysteries in Fairharbour. There always have been.

Around about a decade before I was born, a new mayor was sworn in, who changed the very fabric of the city. Fairharbour was always a place where creative people gathered – there was, maybe, something about its relative remoteness, and peculiar history, that inspired strange ideas in its inhabitants – but when the last mayor of Fairharbour took office, he made sweeping strides towards turning the city into a vibrant creative nexus. A few tax allowances here, a few new creative bursaries there, and suddenly so many bizarre and brilliant new pieces of architecture were being erected; internationally-renowned photographers and composers were moving in; gorgeous new mosaics and fountains were being installed. And all these wonderful, brilliant new artists made new mysteries in the city, overlaying all the old ones.

We still trade tales about the mysterious Smiling Knight, and wonder about some of the more knotted lanes in Silverside, but these days we have mysteries upon mysteries in our winter city: who keeps clearing the snow covering the mosaic of the giant squid in Firmament Square? Why has the Maritime Museum been quarantined since the weatherbomb struck? And – most importantly to me – why do ripe pears keep appearing in Cavalier Heights?

The pears I keep finding at Cavalier Heights have been bothering me for years, and I go there now, striding through the city with such burning purpose that the snow feels as if it melts beneath my boots. The pears might be an answer to a question I didn’t know how to ask until now.

The tower blocks of Cavalier Heights loom taller than the highest spires of any of Fairharbour’s churches. They were one of the last pieces of extraordinary architecture to go up in the city before the weatherbomb struck, a design meant to bring us into the future, where whole communities might live together in awesome, sky-scraping, concrete wonders. Though all their doors have been bricked up, the chill winds have cracked and smashed their windows, and now those very winds whistle through the gaps they have made, making a music that has rendered the apartments unliveable.

This is one of my favourite places in the city. The music of the towers tends to keep most people away, making it a good place to be alone, and there is a sheltered courtyard at the very centre of the blocks where there is a shaded stillness.

I used to live here, on the sixteenth floor of Gallant House with my father, back when the towers were new. The best bit was the roof. The fire escape was never locked, and on clear nights my father would take me up and we would study the planets through his telescopes. My father was an astrologer, and though there was never very much money in it, I feel privileged to have grown up being cared for by someone doing what they love, watching the planets whirl around above and interpreting their influences.

At the centre of the courtyard is an old pear tree, surrounded by an octagon of benches. It’s a wonder that it ever grew before the weatherbomb because it only received slivers of sunshine, and it’s even more impressive that it still seems to be alive today. Most of the time, when I come here, the tree is leafless and inert. But sometimes, on warmer days, there will be tiny green buds in the branches, and ripe pears among its roots.

There are buds in the branches today and there, in the snow, a single ripe pear. I remove my gloves to pick it up, feeling its rough skin. It’s warm, warmer than it should be. I take my kaleidoscope and aim it at the tree. Among the tumbling reflections of its bare branches are glimpses of another pear tree in another city, heavy with leaves and fruit.

I don’t know what it means. I know what it could mean – that there is another version of Fairharbour somewhere out there, maybe next to ours, or below ours. It could mean that, couldn’t it? The small patches of growth that break the snow from time to time aren’t promises of spring, but places where my winter city and their summer city intersect. Places where pears might fall through.

But it might not mean that at all. These thoughts, these wild ideas, might be little more than my imagination, conjuring images in a device I’ve made. Bea always tells me that I have enough imagination for ten people, and that all the movies we watch only fuel it. It would be easy to imagine another place, just beyond the boundaries of the cold, grey familiar, where a person might be warm and well-fed, because that is what I want more than anything in the world to be true.

Only the pear holds me back from complete self-doubt. It is warm, and when I bite into it, it is juicy and delicious and real.

I should tell someone, get a second opinion. But the truth is that I don’t want to. I don’t want Bea, or Henry, to look through my kaleidoscope and tell me that I’m mistaken. I don’t want to be wrong. Some days, I feel as if we are all as bitter as the endless winter.

No, what I want is for my dream to be real. I want there to be a summer Fairharbour. I want the visions through the kaleidoscope to be showing me a warm place that I might go to, or at least reach out to. I want…

I want this to be like a movie.

I finish the pear, savouring every morsel, and imagine what I would do if this was a movie. My next step would be to get in touch with the summer city. So that’s what I decide to do. And I think I know how. It’s obvious, when you think about it in Technicolor.

I find a place among the pear tree’s branches to wedge the kaleidoscope, where it won’t fall. I’m not sure if what I’m doing will have any effect at all. I fully expect to return later and find the device exactly where I am leaving it. But if a pear can pass from a mysterious summer version of Fairharbour into mine, then there is a chance, the smallest chance, that I might be able to send something back.

Satisfied that the kaleidoscope is safely wedged, I turn and make my way over to the tin market, to trade for food.

* * *

Here, then, are the remnants of Fairharbour.

There are tents set up in the gardens of what was once the city newspaper’s offices, the renowned Fairharbour Report. At school, I was taught that the Report began life as a means of distributing the week’s weather to the city’s fishing population. Slowly, articles were added – about the city and beyond it – until the weather was little more than a small column, consigned to the back pages. We were taken on a school trip there, and got to see the reporters in action, converting scribbled notes into typed-up articles, scrutinised by teams of editors. The printing presses in the great halls beneath the offices were so loud that we had to wear ear-guards. I remember being fascinated by the streams of paper, running like rivers from machine to machine, accumulating texts and images as the sheets hurtled through. These days, the Report is empty, and its machines are still.

The tents in the gardens are bustling, however.

Every year, there are fewer people at the tin market. There are plenty of survivors still, huddling in the depths of their houses through the cold, dark nights, but Fairharbour’s artist population were never meant to weather such weather. When the tin market was first raised, it covered half the district – a busy network of tarpaulin tents with enough of a population that it kept a fair amount of warmth; enough to melt the snows all the way down to the hard ground. These days it reaches the edge of the newspaper’s gardens and no further.

There is a heavy Doorman presence.

They check my bag as I enter. There is something about them that makes them feel taller than they actually are – their dark, well-kept uniforms, and warm black masks making them avatars of the city’s authority. A few years ago, the checks were routine and careless – anybody could smuggle anything into the market – but nowadays the Doormen rummage thoroughly, turning over every morsel, and weighing its potential use. They take a fuse from me, and I let it go, passing by with my head bowed. If I put up any fuss, they will accuse me of scavenging and take everything I have. That is the paradox of the market – scavengers are prohibited in the city, but we are all scavengers.

I am glad that I never brought any of the Cavalier Heights pears here. The Doormen would have uprooted the whole tree and taken it back to one of their greenhouses, I’m sure.

I trade the rest of my fuses for a handful of anonymous tins, once I’m inside. I shake each one, but I’ve never been very good at guessing contents, and I am distracted anyway. There are children playing along the aisles, and the smell of hot peaches in the air, and though the faces at the stalls, and the faces that I pass, are grim, it is always warmer at the market.

I am quick with my trades. I can always return with the kaleidoscope and flip it for some more food – oddities are very welcome among the city’s artist scavengers – but I am daring to hope that it might be gone. If it is gone, then my dream can live on for just a little bit longer.

* * *

By the time I return to Cavalier Heights, night is starting to fall.

The winds have started to pick up, and the towers are singing. By the last remnants of daylight I make my way back over to the pear tree, only to find it completely frozen. Winter has reclaimed it. But there is no sign of the kaleidoscope, and there are no boot-prints here except for mine. Nobody has come to take it. The kaleidoscope has vanished.

I spend a while longer checking and double-checking, but it’s nowhere to be found.

Strapping my pack tighter to my back, I begin to make my way home, feeling light of step. Without the kaleidoscope to trade, Bea and I will have to eat sparingly for a few days, but we have always eaten sparingly.

Maybe someone light-of-foot took my kaleidoscope. Maybe it rolled away, in the wind. Maybe it was buried beneath the snow. Or maybe – just maybe – there is another place beyond my city, where there is warmth, and light, and my kaleidoscope is there.

In the twilight I see a figure among the snowdrifts of the main