Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Poetry

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

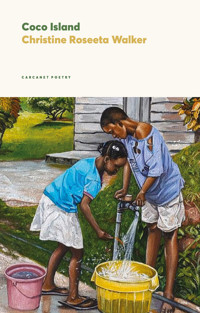

Shortlisted for the OCM Bocas Poetry Prize for Caribbean Literature 2025 Shortlisted for the John Pollard Foundation International Poetry Prize 2025 Christine Roseeta Walker's first book is set entirely in Negril, Jamaica. Coco Island presents a compelling cycle of poems, attentive to the undertow and hidden forces that shape a place and its people. In narrative poems, in songs, in fables, in comic scenes, ghost stories and vivid character sketches – especially of girls and women – Walker artfully lays bare how economic necessity, religious belief, illness and addiction reach far into the structures of family life and community. Piecing together the isolated lives of those left behind as the island modernises, her fearless, memorable poems chart the devastation of a world.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 71

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

3

Coco Island

Christine Roseeta Walker

CARCANET POETRY

Contents

9

For Winston Washington Walker10

COCO ISLAND

ONE

14

Coco Island

From behind the bottle tree, a red sun rises,

shifting colours of pink, orange, and yellow

onto the sand and out into the sea.

From daybreak to nightfall, the Island waits.

Sea-bound, knee-deep in waters too vast

to allow bridges to form between cays.

Each day, glass-bottom boats part waves

to unload the weight of them that come

to dine and dance beneath the bottle tree.

From zinc pits, the scent of meat burning

rises above easy reggae music and euphoric voices

as idle waves lap at the golden sands.

Beneath the bottle tree, they fall in love

with the blue sea and the blue sky blurring,

while the sun turns the evening blood-orange.

But the Island is listening, observing every

gesticulation and conduct until It identifies

them by their attentiveness.

When the Island had hosted them beneath

the bottle tree, they climbed back onto the boats,

delighted to have come to Coco Island.

But often, on the journey back, a sacrifice

must be made — a human offering must be given,

for the Island, too, must feed to survive.

16This is the law of paradise: something taken

for something given. It is Coco Island’s nature —

a muted transaction since its creation.

So, if you should come to Coco Island,

never dance beneath the bottle tree or behave

inattentively: The Island is watching.

Black Sheep

Dusk was near, but not nearby enough

for you to miss your way

onto our verandah.

White dress and hair cut like a man’s,

you sat with your legs wide

squinting into the fading light.

Two strangers we were, each one pretending

to know the other — mother, daughter —

daughter, mother, yet unfamiliar.

The black frock you brought was a funeral dress

puffing out at the hems with layers and layers

of black web… webbing

black with mesh netting to wrap

me in… to haul me away in that giant black bag

nesting at your restless heel.

I look at you without thought

like I did on the last Sabbath day I saw you stumbling

down that slippery slope.

When my father stood with me at the front door,

he said that I was the black sheep —

the black sheep… in your eyes.

And now, on this verandah with the black night

crawling in, all thought escapes me as I gaze

into your blue eyes — who are you?

18What were your excuses, then? Ends meet —

you had left to make ends meet, and now you have returned

holding the ends of a severed circle.

You carried the empty bag to my bedroom in silence,

ate quietly at my brother’s table and listened

as I read from a pile of textbooks.

The small double bed sinking under our weight

as we slip the thin cotton sheet over our feet.

You never talked of those lost years

or said why you had come or why you had with you

that empty bag. At daylight, when the rooster crowed thrice

I awoke from my sleep, you were gone.

A dead-ended telephone number fell off the pillow

onto the floor. I perceive the scourge

in me that had driven you away once more.

Years after my father had died, I saw you again.

But you had gotten smaller. Your blue

eyes were even bluer, still unfamiliar.

At dusk, I listened to you talk on the hotel balcony

and waited quietly for something visceral to happen —

for some pull to guide me.

It was on that night when the light from the moon

had flooded the mango tree that I saw a black shape

sitting in your seat.

The House

It’s the daylight darkness he remembers the most,

the windowless rooms and the rays of grey beams fighting

to float through the twisted stick walls.

He could never find anything in that black house.

But each time he thinks of the darkness, he sees his father

pulling at the end of the galvanised chain holding him to the wall.

The chains were secured in the mornings; his metal mother

chiding him with sharp clinking to stop him straying,

and were removed at night while he watched for empathy.

One morning, he searched the darkness and found the key

to freedom. After work, his worn father caught him

with the neighbours’ kids. The key disappeared for good.

Then, it was just the darkness, the weight of metal

scarfing his neck and the solemn vows to himself

of leaving once he was old enough to depart.

Years later, as he watched his only son playing

with the neighbours’ children, he thought of his father,

trying to understand his lasting cruelty.

At times, he finds himself drawn to the darkness

inside his scarred mind, and to resist, he paints

giant windows on his walls to let the light in.

Like Buffalos

That sweltering June day on the bridge

above the molasses waters of the Negril River

we saw him half-naked and vulnerable.

Passers-by had stopped to watch him

convulse involuntarily towards the riverbank

while hazarding a guess to his ailment.

Spasming, rolling, frothing at the mouth

and moving closer to the water’s pebbled edge,

he had no control of his defeated limbs.

We watched his body fall, rise, fall

thinking of a hundred ways to help, but knowing

we were too weak, too small to pull him back.

The adults looked numbed, petrified,

saying he might grab hold of them if they try

to stop him falling into the glossy marsh.

Our uncle signalled it was time to go

before the stranger rolled down the riverbank,

and plunged into the moving current.

We walked away, trying not to look back,

hearing our uncle’s guttural voice explaining

how quick it takes a human to drown.

21If only people were like buffalos,

it would take him hours before his lungs failed

and enough time to get help, he said.

The stranger had vanished behind

the crowd as we crossed the road to the market,

hoping the murky waters would revive him.22

TWO

24

Totems

Drunk Chaperone

We walked towards the party under a sky of stars

trying not to sway beyond a straight line

like he was. Our uncle, tour guide, tipsy chaperone

swore to show us, children, how to navigate

the night town.

We followed him, three girls, up a hill until we reached

the celebration, confetti floating in the hotel pool.

They served us soda and told us to sit wherever we wanted

while our guide drank rum and coke and quarrelled

with the host.

Minutes later, we followed the curving concrete wall

until we came to the town centre, the sea air raw

on our deflated faces as we climbed the local cinema steps.

Our uncle cajoled the man at the door until he let us in

free of charge.

As we sat down in the dark and crowded picture room,

he stood up, pointed at the screen and shouted,