Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

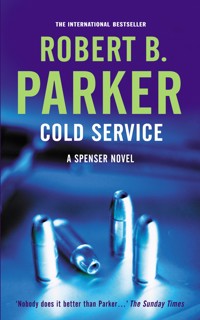

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Spenser Novel

- Sprache: Englisch

When Spenser's closest ally, Hawk, is brutally injured and left for dead while protecting bookie Luther Gillespie, Spenser embarks on an epic journey to rehabilitate his friend in body and soul. Hawk, always proud, has never been dependent on anyone. Now he is forced to make connections: to accept the medical technology that will ensure his physical recovery, and to reinforce the tenuous emotional ties he has to those around him. Spenser quickly learns that the Ukrainian mob is responsible for the hit, but finding a way into their tightly knit circle is not nearly so simple. Their total control of the town of Marshport, from the bodegas to the police force to the mayor's office, isn't just a sign of rampant corruption-it's a form of arrogance that only serves to ignite Hawk's desire to get even. As the body count rises, Spenser is forced to employ some questionable techniques and even more questionable hired guns while redefining his friendship with Hawk in the name of vengeance.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 257

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A Spenser Novel

When Spenser’s closest ally, Hawk, is brutally injured and left for dead while protecting bookie Luther Gillespie, Spenser embarks on an epic journey to rehabilitate his friend in body and soul. Hawk, always proud, has never been dependent on anyone. Now he is forced to make connections: to accept the medical technology that will ensure his physical recovery, and to reinforce the tenuous emotional ties he has to those around him.

Spenser quickly learns that the Ukrainian mob is responsible for the hit, but finding a way into their tightly knit circle is not nearly so simple. Their total control of the town of Marshport, from the bodegas to the police force to the mayor’s office, isn’t just a sign of rampant corruption-it’s a form of arrogance that only serves to ignite Hawk’s desire to get even. As the body count rises, Spenser is forced to employ some questionable techniques and even more questionable hired guns while redefining his friendship with Hawk in the name of vengeance.

Robert B. Parker (1932–2010) has long been acknowledged as the dean of American crime fiction. His novels featuring the wisecracking, street-smart Boston private-eye Spenser earned him a devoted following and reams of critical acclaim, typified by R.W.B. Lewis’ comment, ‘We are witnessing one of the great series in the history of the American detective story’ (The NewYork Times Book Review).

Born and raised in Massachusetts, Parker attended Colby College in Maine, served with the Army in Korea, and then completed a Ph.D. in English at Boston University. He married his wife Joan in 1956; they raised two sons, David and Daniel. Together the Parkers founded Pearl Productions, a Boston-based independent film company named after their short-haired pointer, Pearl, who has also been featured in many of Parker’s novels.

Robert B. Parker died in 2010 at the age of 77.

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR ROBERT B. PARKER

‘Parker writes old-time, stripped-to-the-bone, hard-boiled school of Chandler…His novels are funny, smart and highly entertaining…There’s no writer I’d rather take on an aeroplane’ – Sunday Telegraph

‘Parker packs more meaning into a whispered ‘yeah’ than most writers can pack into a page’ – Sunday Times

‘Why Robert Parker’s not better known in Britain is a mystery. His best series featuring Boston-based PI Spenser is a triumph of style and substance’ – Daily Mirror

‘Robert B. Parker is one of the greats of the American hard-boiled genre’ – Guardian

‘Nobody does it better than Parker…’ – Sunday Times

‘Parker’s sentences flow with as much wit, grace and assurance as ever, and Stone is a complex and consistently interesting new protagonist’ – Newsday

‘If Robert B. Parker doesn’t blow it, in the new series he set up in Night Passage and continues with Trouble in Paradise, he could go places and take the kind of risks that wouldn’t be seemly in his popular Spenser stories’ – Marilyn Stasio, New York Times

THE SPENSER NOVELS

The Godwulf Manuscript

Thin Air

God Save the Child

Small Vices

Mortal Stakes

Sudden Mischief

Promised Land

Hush Money

The Judas Goat

Hugger Mugger

Looking for Rachel Wallace

Potshot

Early Autumn

Widow’s Walk

A Savage Place

Back Story

Ceremony

Bad Business

The Widening Gyre

Cold Service

Valediction

School Days

A Catskill Eagle

Dream Girl (aka Hundred-Dollar

Taming a Sea-Horse

Baby)

Pale Kings and Princes

Now & Then

Crimson Joy

Rough Weather

Playmates

The Professional

Stardust

Painted Ladies

Pastime

Sixkill

Double Deuce

Wonderland (by Ace Atkins)

Walking Shadow

Lullaby (by Ace Atkins)

Chance

THE JESSE STONE MYSTERIES

Night Passage

Stranger in Paradise

Trouble in Paradise

Night and Day

Death in Paradise

Split Image

Stone Cold

Fool Me Twice (by Michael Brandman)

Sea Change

Killing the Blues (by Michael Brandman)

High Profile

Damned If You Do (by Michael Brandman)

THE SUNNY RANDALL NOVELS

Family Honor

Melancholy Baby

Perish Twice

Blue Screen

Shrink Rap

Spare Change

ALSO BY ROBERT B. PARKER

Training with Weights

A Year at the Races (with Joan

(with John R. Marsh)

Parker)

Three Weeks in Spring

All Our Yesterdays

(with Joan Parker)

Gunman’s Rhapsody

Wilderness

Double Play

Love and Glory

Appaloosa

Poodle Springs

Resolution

(and Raymond Chandler)

Brimstone

Perchance to Dream

Blue Eyed Devil

Ironhorse (by Robert Knott)

*Available from No Exit Press

For Joanfar together

REVENGE IS A DISH BEST SERVED COLD

1

It started without me.

‘Bookie named Luther Gillespie hired me,’ Hawk said. ‘Ukrainian mob was trying to take over his book.’

‘Ukrainian mob?’ I said.

‘Things tough in the old country,’ Hawk said. ‘They come here yearning to breathe free.’

‘Luther declined?’

‘He did. They gave him twenty-four hours to reconsider. So he hired me to keep him alive.’

A dignified gray-haired nurse in a sort of dressy flowered smock over her nurse suit came into the hospital room and checked one of the monitors tethered to Hawk. Then she nodded, tapped an IV line and nodded again and smiled at Hawk.

‘Is there anything you need?’ she said.

‘Almost everything,’ Hawk said. ‘But not right now.’

The nurse nodded and went out. Through the window I could see the sun in the west reflecting off the mirrored surface of the Hancock Tower.

‘I’m guessing that didn’t go so well,’ I said.

‘We’re on the way to his house, on Seaver Street, somebody from a window across the street shoots me three times in the back with a big rifle. Good shooter, grouped all three shots between my shoulder blades. Missed the spine, missed the heart, plowed up pretty much of the rest.’

‘The heart I’m not surprised,’ I said, ‘being as how it’s so teeny.’

‘Don’t go all mushy on me,’ Hawk said. ‘I wake up, here I am in a big private room and you be sitting in the chair reading a book by Thomas Friedman.’

‘Longitudes and Attitudes,’ I said.

‘Swell,’ Hawk said. ‘How come I got this room?’

‘I know a guy,’ I said.

‘When I go down, they go on after Luther and kill him and his wife and two of his three kids. The youngest one was in day care.’

‘Object lesson,’ I said. ‘For the next guy, they push.’

Hawk nodded again.

‘Where’s the youngest kid?’

‘With his grandmother,’ Hawk said. ‘They tell me I ain’t going to die.’

‘That’s what I heard,’ I said.

There were hard things being discussed, and not all of them aloud.

‘I want to know who they are and where they are,’ Hawk said.

I nodded.

‘And I want to know they did it,’ Hawk said. ‘Not think it, know it.’

‘When are you getting out?’ I said.

‘Maybe next week.’

‘Too soon,’ I said. ‘You won’t be ready even if we know who and where.’

‘Sooner or later,’ Hawk said, ‘I’ll be ready.’

‘Yeah,’ I said. ‘You will.’

‘And I’ll know it when I am.’

‘And when you are,’ I said, ‘we’ll go.’

We were on the twenty-second floor in Phillips House at Mass General. All you could see from where we were was the Hancock Tower gleaming in the setting sun. Hawk looked at it for a while. There was no expression on his face. Nothing in his eyes.

‘Yeah,’ he said. His voice was uninflected. ‘We will.’

2

I stopped by pretty much every day to visit Hawk. One day when I arrived, I saw Junior and Ty Bop lingering in the hallway outside his room. Both were black. Junior took up most of the corridor. Fortunately, Ty Bop weighed maybe one hundred thirty pounds, so there was room to get by. I smiled at them cordially. Junior nodded. Ty Bop paid me no attention. He had eyes like a coral snake. Neither meanness nor interest nor affection nor recognition showed in them. Nor humanity. Even standing still, he seemed jittery and bouncy. Nobody on the floor or at the nursing station ventured near either of them.

‘Tony inside?’ I said to Junior.

He nodded and I went in. Tony Marcus was standing by the bed, talking to Hawk. Tony’s suit must have cost more than my car. And he was good-looking, in a soft sort of way. But that was illusory. There was nothing soft about Tony. He pretty much ran all the black crime in eastern Massachusetts, and soft people didn’t do that. Tony looked up when I came in.

‘Well, hell, Hawk,’ Tony said. ‘No wonder people shooting your ass. You got him for a friend.’

I said, ‘Hello, Tony.’

He said, ‘Spenser.’

‘Tony and me been talking ’bout the Ukrainian threat,’ Hawk said.

‘They come to this country,’ Tony said, ‘and they look to get a foothold and they see that nobody in America much care what happen to black folks, so they move on us.’

‘Got any names?’ I said.

‘Not yet,’ Tony said. ‘But I’m planning to defend my people.’

‘Tony bein’ Al Sharpton today,’ Hawk said.

‘Don’t you have no racial pride, Hawk?’ Tony said.

Hawk looked at Tony without speaking. He had three gunshot wounds and still could barely stand, but the force of his look made Tony Marcus flinch.

‘I’m sorry, man,’ Tony said. ‘I take that back.’

Hawk said, ‘Yeah.’

‘I tellin’ Hawk he ought to let me put a couple people in here, protect him. Until he’s on his feet again.’

‘Nobody got any reason to follow up,’ Hawk said. ‘They done what they set out to do.’

‘I think that’s right,’ I said.

Tony shrugged.

‘’Sides,’ Hawk said. ‘Vinnie’s been in and out. Susan’s been here. Lee Farrell. Quirk and Belson, for chrissake. There’s been a steady parade of good-looking women worrying where I’d been hit. Plus, I got a phone call from that Chicano shooter in L.A.’

‘Chollo?’ I said.

‘Yeah. He say I need a hand he’ll come east.’

‘See that,’ I said. ‘I told you that warm and sunny charm would pay off in friendship and popularity.’

‘Must be,’ Hawk said.

‘Well,’ Tony Marcus said, ‘I got a vast criminal enterprise to oversee. I’ll be off. You need something, Hawk, you give me a shout.’

Hawk nodded.

‘Say so long to Ty Bop for me,’ I said.

‘He try to bite you when you came in?’ Tony said.

‘No.’

‘See that,’ Tony said. ‘He like you.’

After Tony left, I sat with Hawk for about an hour. We talked a little. But a lot of the time we were quiet. Neither of us had any problem with quiet. I looked at the Hancock Tower; Hawk lay back with his eyes closed. I had known Hawk all my adult life, and this was the first time, even in repose, that he didn’t look dangerous. As I looked at him now, he just looked still. When it was time to go, I stood.

‘Hawk,’ I said softly.

He didn’t open his eyes.

‘Yeah?’ he said.

‘Got to go.’

‘Do me a favor,’ he said with his eyes closed.

‘Yeah.’

‘Have a drink for me,’ he said.

‘Maybe two,’ I said.

Hawk nodded slightly without opening his eyes.

I put my hand on his shoulder for a moment, took it away, and left.

3

I was in my office having a cup of coffee and looking up Ukraine on the Internet. Like most of the things I looked up on the Internet, there was less there than met the eye. But I did learn that Ukraine was a former republic of the Soviet Union, now independent. And that kartoplia was Ukrainian for potato. I knew if I kept at it I could find a Ukrainian porn site. But I was spared by the arrival of Martin Quirk in my office, carrying a paper bag.

‘Did you know that kartoplia means potato in Ukrainian?’ I said.

‘I didn’t,’ Quirk said. ‘And I don’t want to.’

I pointed at my Mr Coffee on top of the file cabinet.

‘Fresh made yesterday,’ I said. ‘Help yourself.’

Quirk poured some coffee.

‘You got donuts in the bag?’ I said.

‘Oatmeal-maple scones,’ Quirk said.

‘Scones?’

‘Yep.’

‘No donuts?’

‘I’m a captain,’ Quirk said. ‘Now and then I like to upgrade.’

‘How do you upgrade from donuts?’ I said.

Quirk put the bag on the desk between us. I shrugged and took a scone.

‘Got to keep my strength up,’ I said.

Quirk put his feet up on the edge of my desk and munched on his scone and drank some coffee.

‘Two days ago,’ Quirk said, ‘couple of vice cops are working a tavern in Roxbury, having reason to believe it was a distribution point for dope and/or whores.’

The maple-oatmeal scone wasn’t bad, for a non-donut. Outside my window, what I could see of the Back Bay had an authentic gray November look with a strong suggestion of rain not yet fallen.

‘So the vice guys are sipping a beer,’ Quirk said. ‘And keeping an eye out, and two white guys come in and head for the back room. There’s something hinky about these guys, aside from being the only white men in the room, and one of the vice guys gets up and goes to the men’s room, which is right next to the back room.’

Quirk was not here for a chat. He had something to tell me and he’d get to it. I ate some more scone. The oatmeal part was probably very healthy.

‘The guy in the men’s room hears some sounds that don’t sound good, and he comes out and yells to his partner, and in they go to the back room with their badges showing and guns out,’ Quirk said. ‘The tavern owner’s had his throat cut. The two white guys are heading out. One of them makes it, but the vice guys get hold of the other one and keep him.’

‘Tavern owner?’ I said.

‘Dead before they got there; his head was almost off.’

‘And the guy you nabbed?’

‘Cold,’ Quirk said. ‘The dumb fuck is still carrying the knife, covered with the vic’s blood, on his belt. Big, like a bowie knife, expensive, I guess he didn’t want to leave it. And the vic’s blood is all over his shirt. ME says they tend to gush when they get cut like that. So we bring him in and we sweat him. He speaks English pretty good. His lawyer’s there, and a couple of Suffolk AD’s are in with us, and after a while he sees the difficulty of his position. He says if we can make a deal he can give us his partner, and if the deal’s good enough he can give us the people shot that family over by Seaver Street.’

I was suddenly aware of my breath going in and out.

‘Do tell,’ I said.

‘I was in there at the time and I said “family named Gillespie?” He said he didn’t know their names but it was over by Seaver Street and it was the end of October. Which is right, of course. And I said, “How about the rifle man that shot the bodyguard.” And he said, “No sweat.”’

‘He Ukrainian?’ I said.

‘Says so.’

‘What’s his name?’

‘Bohdan something or other,’ Quirk said. ‘I got it written down, but I can’t pronounce it anyway.’

‘Did he give you the others?’

‘Yes. His lawyer fought him all the way. But Bohdan isn’t going down for this alone, and he does it even though his lawyer’s trying to stop him.’

‘Think the lawyer was looking out for him?’ I said.

‘Not him,’ Quirk said.

‘Bohdan’s a mob guy,’ I said.

‘Seems like,’ Quirk said.

‘And his lawyer’s probably a mob lawyer.’

‘Seems like,’ Quirk said.

‘And you got the others?’

Quirk smiled.

‘Five in all,’ he said.

‘Including Bohdan?’

‘Including him,’ Quirk said.

‘They all Ukrainian?’ I said.

‘I guess so. Except for Bohdan, they all swear they don’t understand English, and Ukrainian translators are hard to come by. We had to get some professor from Harvard to read them their rights.’

‘Maybe you should keep him on,’ I said.

‘Too busy,’ Quirk said. ‘He’s finishing a book on …’ Quirk took out a small notebook, opened it, and read from it. ‘… the evolution of Cyrillic language folk narratives.’

I nodded.

‘That’s busy,’ I said. ‘Can I have another scone?’

Quirk pushed the bag toward me.

‘You think it’ll make Hawk happy?’

‘Not sure,’ I said.

‘You think he’d rather have done it himself?’

‘Not sure of that either,’ I said. ‘Hawk is sometimes difficult to predict.’

‘No shit,’ Quirk said.

4

In the afternoon on Thursday, late enough to be dark, with the rain coming hard, I walked down Boylston Street to have a drink with Cecile in the bar at the Four Seasons. We sat by the window looking out at Boylston Street with the Public Gardens on the other side. Cecile was wearing a red wool suit with a short skirt and looked nearly as good as Susan would have in the same outfit. A lot of people looked at us.

‘Hawk asked me to talk with you,’ I said.

She nodded.

‘You know his situation?’

She nodded again. The waiter came for our order. Cecile had a cosmopolitan. I asked for Johnnie Walker Blue and soda.

‘Tall glass,’ I said. ‘Lot of ice.’

The waiter was thrilled to get our order and delighted to comply. There was considerable traffic on Boylston, backing up at the Charles Street light. There were fewer pedestrians. But enough to be interesting, collars up, hats pulled down, shoulders hunched, umbrellas deployed.

‘I know his surgeon,’ Cecile said. ‘We were at Harvard Med together.’

‘And he’s filled you in?’

‘Well,’ Cecile said with a faint smile. ‘He respects patient confidentiality, of course … but I am reasonably abreast of things.’

‘Hawk wants me to explain to you,’ I said.

‘Explain what?’ she said.

‘Him,’ I said.

‘Hawk wants you to explain him to me?’

‘Yes.’

Cecile sat back with her hands resting on the table and stared at me. The waiter came with the drinks and set them down happily, and went away. Cecile took a sip of her drink and put it back down and smiled.

‘Well,’ she said, ‘I guess I’m flattered that he cares enough to ask you … I think.’

‘That would be the right reaction,’ I said.

‘I could have considered it possible that I knew him well, and perhaps even in ways that you don’t,’ Cecile said. ‘For God’s sake, you’re white.’

‘That would be another possible reaction,’ I said.

Cecile drank some more cosmopolitan. I had some scotch.

‘How long have you known Hawk?’ she said.

‘All my adult life.’

‘How old were you when you met him?’

‘Seventeen.’

‘Good God,’ Cecile said. ‘It’s hard to imagine either of you being anything but what you are right now.’

‘Hawk wants you to understand why he doesn’t want you to visit.’

‘He doesn’t need to explain,’ Cecile said.

‘He doesn’t want you to see him when he isn’t … when he is, ah, anything but what he has always been.’

Cecile nodded. She was looking at her drink, turning the stem of the glass slowly in her fingers.

‘I am a thoracic surgeon,’ she said. ‘I am a black, female thoracic surgeon. Do you have any guess how many of us there are?’

‘You’re the only black female surgeon I know,’ I said.

‘Surgery is still mostly for the boys. If you’re a woman and want to be a surgeon, you need to be tough. If you are a black woman and want to do surgery …’

She drank a little more.

‘I do not,’ she said, ‘need a man to protect me. I don’t need one who can’t be hurt.’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I think Hawk knows that.’

She raised her eyebrows.

‘But he needs to be that,’ I said. ‘Not for you. For him.’

‘That’s childish,’ Cecile said.

‘He knows that,’ I said.

‘He could change,’ Cecile said.

‘He doesn’t want to. That’s the center of him. He is what he wants to be. It’s how he’s handled the world.’

‘The world being a euphemism for racism?’

‘For racism, for cruelty, for loneliness, for despair … for the world.’

‘Does that mean he can’t love?’

‘I don’t know. He doesn’t seem to hate.’

‘It’s a high price,’ she said.

‘It is,’ I said.

‘I’m black.’

‘That doesn’t make you just like Hawk,’ I said.

‘I don’t have to pay that kind of price.’

‘You’re not just like Hawk.’

‘Neither are you,’ she said.

‘No,’ I said, ‘neither am I.’

‘So what are you saying?’

‘I’m saying he can’t see you until he’s Hawk again. His Hawk. And he cares enough about you to want me to explain it.’

‘I’m not sure you have,’ Cecile said.

‘No. I’m not sure I have, either,’ I said.

‘Have you ever been hurt like this?’ Cecile said.

‘Yes.’

‘Did you want to be alone?’

‘Susan and Hawk were with me. But the circumstance was different.’

The waiter drifted solicitously by. I nodded. He paused. I ordered two more drinks. Cecile looked out the window for a while.

‘You love her,’ Cecile said.

‘I do.’

‘Is there a circumstance in which you would not want her with you?’

‘No.’

Cecile smiled again.

‘How about if you’re cheating on her?’ she said.

‘I wouldn’t do that,’ I said.

‘Have you ever?’

‘Yes.’

‘But you won’t again.’

‘No.’

‘She ever cheat on you?’

‘She has.’

‘But she won’t again.’

‘No.’

Cecile smiled without any real humor.

‘Isn’t that what they all say?’

‘It is,’ I said.

I sipped some scotch. Rain ran down the window, the streets gleamed. The scotch was excellent.

‘You’re not going to argue with me?’

‘About what they all say?’

‘Yes.’

‘No,’ I said.

Cecile studied me for a time.

‘You’re more like him than I thought,’ she said.

‘Hawk?’

She nodded.

‘I have never heard him defend himself or explain himself,’ she said. ‘He’s just fucking in there, inside himself, entirely fucking sufficient.’

There was nothing much to say to that. Cecile drank the rest of her cosmopolitan.

‘And except for being white, I think you are just goddamned fucking like him,’ she said.

‘No,’ I said. ‘I’m not.’

She was studying my face like it was the Rosetta Stone.

‘Susan,’ she said. ‘You need Susan.’

‘I do.’

‘Well, he doesn’t need me.’

‘I don’t know if he does or not,’ I said. ‘But not wanting to see you now doesn’t prove it either way.’

‘If he doesn’t need me now, when will he?’

‘Maybe need is not requisite to love.’

‘It seems to be for you,’ she said.

‘Maybe that would be my weakness,’ I said.

‘Maybe it’s not a weakness,’ she said.

‘Maybe an infinite number of angels,’ I said, ‘can balance on the point of a needle.’

She nodded. The waiter brought her another drink.

‘We are getting a little abstract,’ she said.

‘I don’t know if he loves you,’ I said. ‘And I don’t know if you love him. And I don’t know if you’ll stroll into the sunset together, or should or want to. But as long as you know Hawk, he will be what he is. He’s what he is now, except hurt.’

‘And being hurt is not part of what he is?’ she said.

I grinned.

‘It is, at least, an aberration,’ I said.

‘So if I’m to be with him, I have to take him for what he is?’

‘Yes.’

‘He won’t change.’

‘No.’

‘And just what is he?’ Cecile said.

I grinned again.

‘Hawk,’ I said.

Cecile took a sip of her drink and closed her eyes and tilted her head back and swallowed slowly. She sat for a moment like that, with her eyes closed and her head back. Then she sat up and opened her eyes.

‘I give up,’ she said.

She raised her glass toward me. I touched the rim of her glass with the rim of mine. It made a satisfying clink. We both smiled.

‘Thank you,’ she said.

‘I’m not sure I helped.’

‘Maybe you did,’ she said.

5

Hawk and I went to a meeting with an assistant prosecutor in the Suffolk County DA’s office in back of Bowdoin Square. It wasn’t much of a walk from the hydrant I parked on One Bullfinch Place, but Hawk had to stop halfway and catch his breath.

‘Be glad when my blood count get back up there.’

‘Me too,’ I said. ‘I’m sick of waiting for you all the time.’

He looked bad. He’d lost some weight, and since he didn’t have any to lose, his muscle mass was depleted. He still seemed to walk slightly bent forward, as if to protect the places where the bullets had roamed. And he looked smaller.

The meeting room was on the second floor – in front, with three windows, so you could look at the back of the old Bowdoin Square telephone building. Quirk was already there, at the table, with a Suffolk County ADA, a fiftyish woman named Margie Collins, whom I had met once before.

‘Hawk,’ Quirk said. ‘You look worse than I do.’

‘Yeah, but I is going to improve,’ Hawk said.

Quirk smiled and introduced Margie, who didn’t seem to remember that she’d met me once before. Since Margie was still quite good-looking, in a full-bodied, still-in-shape, blond-haired kind of way, her forgetfulness was mildly distressing.

‘Our eyewitness shit the bed,’ Margie said when we sat down.

‘Stood up in court and said he had been coerced by the police,’ Quirk said. ‘Didn’t know the defendants. Didn’t know anything about any crimes they’d committed. He was our case. Judge directed an acquittal.’

Hawk was quiet. For all you could tell, he hadn’t heard what was said.

‘How’d they get to him?’ I said.

‘We had him in the Queen’s Inn,’ Quirk said. ‘In Brighton. Two detectives with him all the time. Nobody in. Nobody out.’

‘Except his lawyers,’ Margie said.

‘Bingo,’ I said.

‘Yeah. Can’t prove it. But when we flipped him in the first place, his lawyer was fighting us all the way.’

‘Did I hear you say lawyers?’ I said.

‘Yes,’ Margie said. ‘The second one was in fact an attorney. We checked. But I’m sure he was the one carried the message.’

‘What does whatsisname get for bailing on his deal.’

‘Bohdan,’ Quirk said.

‘He does life,’ Margie said.

‘Which is apparently a better prospect than the one they offered him,’ I said.

‘Apparently,’ Margie said.

She looked at Hawk.

‘I’m sorry,’ she said. ‘We can’t shake him.’

Hawk smiled gently.

‘Don’t matter,’ he said.

‘At least the man who shot you will do his time.’

‘Maybe,’ Hawk said.

‘I promise you,’ Margie said.

‘He ain’t going to do much time,’ Hawk said.

Quirk was looking out the window, studying the back of the building as if it was interesting.

‘They gonna kill him in prison,’ Hawk said. ‘If he gets there. He rolled on them once. They won’t take the chance.’

Margie looked at Quirk. Quirk nodded.

‘Be my guess,’ Quirk said.

Margie looked at me.

‘And what is your role in all of this?’ she said.

‘Comic relief.’

‘Besides that.’

‘My friend dodders,’ I said. ‘I have to hold his arm.’

‘Don’t I know you from someplace?’ Margie said.

‘I swept you off your feet about fifteen years ago, insurance fraud case, with a shooting?’

‘Ah,’ Margie said. ‘That’s when. You remember that as sweeping me off my feet?’

‘I like to be positive,’ I said.

Margie nodded slowly. Then she looked at Hawk.

‘I’ve heard about you,’ she said. ‘You may want to deal with this problem on your own.’

Hawk smiled.

‘And I can’t say that I’d blame you,’ she said. ‘But if you do, and we catch you, I will be sympathetic, and I will do everything I can to put you away.’

‘Everybody do,’ Hawk said.

‘Meanwhile, we’ll stay on this thing,’ Margie said. ‘It’s a horrific crime. But honestly, I’m not optimistic. What we had was the witness.’

‘And now you don’t,’ Hawk said.

‘And now we don’t,’ Margie said.

‘And they been acquitted.’

‘Yes.’

‘And double jeopardy apply.’

‘Yes.’

Hawk stood slowly. I stood with him.

‘When they kill him,’ Hawk said. ‘Maybe you can get them for that.’

‘We’ll try to prevent that,’ Margie said.

‘No chance,’ Hawk said.

He turned slowly toward the door, one hand holding the back of his chair.

‘We’ll catch them sooner or later for something,’ Margie said. ‘These are habitual criminals. They aren’t likely to change.’

‘Thanks for your time,’ Hawk said.

‘I’ll have coffee with you,’ Quirk said. ‘Margie, we’ll talk.’

She nodded, and the three of us went out. Slowly.

6

We walked slowly to a coffee shop on Cambridge Street. If Quirk noticed that Hawk was shuffling more than he was walking, he didn’t comment.

All he said was, ‘You back in the gym yet?’

‘Nope,’ Hawk said. ‘But ah has started to brush my own teeth.’

‘Step at a time,’ Quirk said.

We got coffee. Quirk took a thick manila envelope out of his briefcase and put it on the table.

‘If I go before you do and forget this, and leave it lying here on the table, I want you to return it to me immediately. I only got two other copies. And under no circumstances do I want you to open the envelope and read its contents.’

‘Where my man, Bohdan?’ Hawk said.

‘In jail awaiting trial,’ Quirk said.

‘Suffolk County?’ Hawk said.

‘Yep.’

‘Think he’ll last till his trial?’ Hawk said.

‘He thinks so,’ Quirk said. ‘He thinks everything’s hunky-dory with the other Ukrainians.’

‘You keeping him separate?’ I said.

‘Yep.’

Hawk made a soft, derisive sound.

‘Never going to make trial,’ Hawk said.

Quirk shrugged.

‘And ain’t that a shame,’ Quirk said.

‘What have you got on the rest of them?’ I said.

‘The details are, of course, confidential police business, which is why I have them sealed up safe in this envelope. We been talking to the organized-crime guys, the FBI, immigration. We know it’s a Ukrainian mob. Which means we are dealing with some very bad people. Even the Russians are afraid of the Ukrainians.’

‘They straight from the old country?’ I said.

Quirk shook his head.

‘We think from Brooklyn. They’ve set up around here in Marshport, up on the North Shore, which has got a small Ukrainian population.’

I nodded.

‘They come in, start small. Take over a book here and horse parlor there. Usually small-time black crime. The assumption being that the blacks have the least power.’

Quirk grinned at Hawk.