Howell Davies was born in 1896 on a farm at Felingwm near Carmarthen. He joined the Royal Welch Fusiliers on his 18th birthday in 1914 and served throughout the First World War, being wounded twice and commissioned Captain. Educated at the Sorbonne, Oxford and Aberystwyth University, he became a freelance journalist and editor for a wide variety of publications and organizations. He was editor ofThe South American Handbook, from 1923 until 1972. His best-known works are the three novels published by Gollancz just before the outbreak of the Second World War, most notablyMinimum Man(1938), which was widely serialized. This was followed in 1939 byThree Men Make a WorldandCongratulate the Devil. Howell Davies died in 1985.

foreword

‘No, no, I’m Welsh actually’ is always my riposte when accused of being English, partly to avert the cliché of being just one more Englishman living in New York, but mostly as homage to the very Welshness of my grandfather Howell Davies. This notable Welshness was not a question of mere nationality, though he was born on the hills of Felingwm, nor of language, though he indeed spoke and wrote Welsh with pride and accomplishment, but rather of character and attitude, his unique approach to the whole thing of it.

Thus I grew up with the sense, never stated nor defined, that Welshness required verbal wit and linguistic dexterity in whatever tongue it might be expressed, a cunning born of a long history of being the minority, the marginal, maverick even. That to be Welsh was to prefer the amusing or outrageous over the factual and actual, to believe the imagination more vital than any reality and that all liberties taken with the truth were proof of one’s ultimate loyalty to those most important things of all, the story, song, poem.

By the time I knew my grandfather he was more or less retired and though I was aware he had been a writer, I thought of him rather as a reader, talker, pipe-smoker, sage and wit, the one adult who would come up with something scandalous, inappropriate or just funny. So much of my childhood seemed to be spent at that small, bright pink cottage, Number Two Pond Square, right at the top of Highgate Hill, a magical place of narrow stair and tiny rooms with the scent of books, newspapers and literary journals, pipe smoke and coffee.

Here Howell would eat his rice-pudding every day, hand- grind his own beans in the kitchen, read his copy of The Times at the worn-smooth table in the downstairs living- room, always keeping an eye on the square outside, to spot an old friend or spy a new potential one coming by. For Howell always loved to meet new people, preferably young, ideally writers or those involved in the arts, and sometimes to this end he would sit outside on the low brick wall of his front yard, puffing away in his Parisian beret, accosting suitable strangers.

Though he spoke a good deal, Howell had the supreme elegance of never talking about himself, least of all if he felt unwell, and never referring to the years he had suffered in the trenches of the First World War. There was a shiny bronze shell canister used as an umbrella stand in the hallway and down in the basement there was a captured German helmet, as well as his own Tommy’s helmet shockingly pierced with shrapnel from when he had been so seriously wounded, but he said nothing.

He also never spoke of his own life as a writer, nor did he really care about keeping copies of his innumerable articles, short stories, radio scripts, plays and essays; that archival instinct must have seemed pompous or pointless, alien to his inherently anarchic nature. Thus it was only much later that I discovered the few battered books he had bothered to keep on his shelves, as if by chance, and was happily able to appreciate his prolific career as journalist, script-doctor, travel guide editor and science fiction novelist.

Howell, or Hywel as he sometimes spelt it, was born on 3rd September 1896 at Court Farm, Felingwm, near Carmarthen, one of eight children in a respectable if surely far from rich farming family. This rural upbringing was a source of certain nostalgia as well as earthy comedy, and he enjoyed telling tales of farming life, trapping a vicious swan’s neck under the tine of a fork, singing at chapel, playing tricks on his brothers. These siblings went on to successful careers in education, science and medicine, suggesting that Howell perhaps slightly exaggerated the rustic simplicity of their origins.

The war obviously changed everything. Howell volunteered for the Royal Welch Fusiliers on the very day of his eighteenth birthday in the summer of 1914. As a foot soldier Howell must have seen the very worst of the war, the brutal reality recorded in two small wartime field diaries, both later transcribed and donated to the Royal Welch Fusiliers’ Regimental Museum at Caernarfon Castle. One of these is from his first year of active service and the other presumably from 1917 as it mentions the Russian revolution.

During those very long years Howell was not only promoted to Captain but also wounded twice, the second time sufficiently seriously in the head to recuperate back in Wales. It was here that he met Robert Graves, who was to become a permanent off-and-on friend, a professional colleague if not mentor. As Graves puts it in Goodbye to All That: ‘Few officers in the battalion had seen any active service. Among the few was Howell Davies (now literary editor of the Star), who had a bullet through his head and was in as nervous a condition as myself. We became friends, and discussed the war and poetry late at night in the hut; we used to argue furiously, shouting each other down.’

Immediately after the armistice Howell took advantage of his veteran status to enrol at the Sorbonne, and though he was not there for long and failed to garner any actual academic qualification, as a handsome young officer he surely fully sampled Parisian café cultural life of the era. Whilst doubtless ‘arguing furiously and shouting down’ a wide variety of other bohemians Howell did manage to meet certain celebrities from this community of exiles, most notably James Joyce. Indeed Howell even owned a first edition of Ulysses, whether signed or not always remained a moot detail, eventually given to one of those ambiguous, ill-defined female ‘friends’ he seemed to easily accumulate. Likewise his impressive ‘Bardic Chair’, supposedly won at some unspecified Eisteddfod, was given to a female friend to decorate her fashion boutique. These friends, often of a strong literary or artistic bent themselves, may well have interfered with more formal scholarly obligations. For, right after the Sorbonne, Howell went up to Oxford only to come down again remarkably rapidly amongst rumours of romance, though he always remained a sworn enemy of Cambridge in their annual boat race.

Howell then continued his education at Aberystwyth, where again he refused matriculation, describing himself as leaving the place ‘degreeless and inconsolable’. This comes from a surprisingly honest essay by Howell in the 1928 anthology College by the Sea, where he admits ‘I learnt at Aberystwyth that it is not life that matters. It is the way you get out of it.’

He also described the effect of all those returning ex- servicemen: ‘We fought for extended bounds. We got them. We wanted to meet the women in cafes, in cinemas. We wanted to walk with them into the country. It was given us, after a most undignified scuffle. We clamoured for booze, for the right to enter public houses. Some of us were drunk with vain glory.’

Howell did, however, successfully edit the college magazine Y Ddraig (The Dragon) during 1920–21 and was proud of the important papers they published, including the inaugural address of his only local hero Alfred Zimmern, who had just been appointed first Woodrow Wilson Chair of International Politics.

Howell concluded: ‘speaking honestly for myself, I remember with joy… only the wooing of my wife.’ For it was at Aberystwyth that he met Enid Margaret Beckett, my mother’s mother, and married her, though not without opposition. For ‘Becky’, as she was known, was from an altogether more solid background, her father Thomas Beckett being Senior Wrangler at Cambridge, with a maths theorem named after him, and longtime head of mathematics at St Paul’s School, whilst her mother, Zoe Stevenson, was a direct cousin of Robert Louis from Edinburgh. By contrast, Howell had no degree and no visible means of support, having happily found occasional employment making Lyons Swiss rolls or selling encyclopaedias door-to-door.

However, by 1923 Howell had not only won a Cassell’s Weekly essay competition on ‘Is There A New Wales?’ he had also found work with Trade & Travel Publications Ltd, a company affiliated with the White Star Shipping Line, which put out a series of compact, hardback guides crammed with information. The most famous of these, still published today, is The South American Handbook, a thoroughly detailed compendium of information on that continent which Howell single-handedly created as its inaugural editor in 1923. Impressively he continued to create this chunky tome every year for the following four decades, being called out of retirement to edit it again in the late sixties, his final volume coming out in 1972, a full fifty years after the first.

Howell naturally had an extensive network of contacts and correspondents throughout those countries and the faintest wisp of clandestine communication if not actual espionage accompanied their activities. Appropriately Graham Greene called it ‘the best travel guide in the world’, Howell also became something of a media pundit on the whole region. Hearing him pontificate on the radio about revolution in Bolivia or inflation in Argentina, only his immediate family were probably aware he had never been anywhere near South America and in fact regularly refused free shipping-line trips there. For Howell was not a great traveller and apart from walking tours of the Black Forest and an early enthusiasm for skiing, or ‘scheeing’ as it was then called, preferred London, if not Highgate itself, and the wider domain of imagination.

Howell also edited The Traveller’s Guide to Great Britain

& Ireland (1930) and an accompanying Spanish version, Anuario de la Gran Bretaña, where we learn that: ‘Gales es un país aparte de Inglaterra, con lengua propria y distinta característica nacional y de rica y variada hermosura. El interior es magnifico e inspirador.’

Howell also worked for a long a time for the BBC, but always as a fiercely independent freelancer refusing any staff contract whilst pounding out the widest possible variety of material, much of it describing particularly British topics, whether Dr Barnardo’s or the bowler, for the Overseas Service. He much enjoyed that BBC Broadcasting House social culture of the period, and was an habitué of the neighbouring pubs of Fitzrovia and Soho as well as the Café Royal. With his flair for friendship Howell maintained a generous roster of higher acquaintances, whether poets such as Dylan Thomas, Robin Leanse and Dannie Abse, science fiction writer John Wyndham, Alison Waley or Laurence Gilliam, head of BBC Features. Another poet-friend was Alun Lewis, whose biography by John Pikoulis grants some sense of Howell’s lure: ‘Alun was equally pleased to meet a conversationalist of the greatest vivacity, purveyor of the higher gossip, literary and political.’ Howell, he thought, had ‘said many sharp and illuminating things as well as helped me to find a general sense of purpose and direction.’

But Howell wrote as much as he talked; such as ‘The Five Eggs’ included in Welsh Short Stories: A Collection of Best Stories by Famous Authors (Faber 1937) or a full- length play The Mayor, staged by The Repertory Players for one-night, 6 May 1951, at Wyndhams Theatre, with its cast including the young Alec McCowen.

And then there are the novels, a trio of science fiction/ fantasy books published by Victor Gollancz between 1938 and 1939, books Howell himself never mentioned and which, due to the strange nom de plume ‘Andrew Marvell’, forced upon him by his publisher, few realised were his own work. Of these, the first, Minimum Man, was the most successful, a veritable bestseller, serialised in the evening paper, republished by the Science Fiction Book Club in 1953, and in August 1947 issued in an unauthorized version by American pulp magazine Famous Fantastic Mysteries, with striking cover-art by illustrator Virgil Finlay. Certainly the book is included in most of the reference works and web sites devoted to the fantasy genre and its theme, of the next stage of human evolution being a new race of tiny beings attempting to push us aside, struck some acute public nerve of the era.

The following novel, Three Men Make a World, might seem the most topical as it concerns the deliberate sowing of a chemical bacterium that contaminates all petroleum, jams every form of oil-based consumption, and brings contemporary transportation and existence as we know it to an end.

The book is overtly anti-capitalist if not ‘green’, and is clearly ahead of its time in an almost beatnik attitude, featuring a central character from a wealthy background who rejects it all in the quest for an existential freedom from consumer goods and society’s mores. ‘He wanted, in a way, to sing, to have flowers in his hair. That was it. You could sum up the general temper of his desires by saying that he wanted flowers in his hair, to trip it through life, gay, happy, unoppressed by material considerations…’ Even Seán O’Faoláin gave ‘Three asterisks for this yarn, which combines excitement and uplift in a melange not too high- or low-brow for any common reader.’

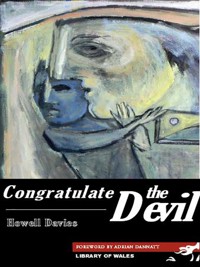

Congratulate the Devil is the third, last, least known and hardest to find, probably due to the outbreak of war just after it was published in 1939. It is as fantastical as the others and in its casual discussion of mescaline-based hallucinogens also has something of an avant-tang of the later counter-culture. But I do not want to give anything away regarding this book’s truly bizarre plot, a narrative that whilst highly improbable does obey its own odd logic. It is stylistically very much of its time, the late and fevered 1930s, darting forth out of its quick-fire patter and rapid scene-cutting; dated of course, but on the whole more amusingly than annoyingly, with a certain durability to aphorisms such as ‘Every Man has a book and a crime in him, and many people commit both, once.’ There is also the rather disconcerting effect of having what is now London’s revered Serpentine Gallery for contemporary art blown sky high by artillery shells. It is the most Welsh of all Howell’s books, beginning and ending in Wales and featuring a most amiable Welsh ‘wandering minstrel’, naturally an unemployed one, as a central character; and it is packed with Howell’s remarks

regarding his nation and its apparently curious ways.

‘For that was the worst of being Welsh, once you got into the spirit of a thing, and though you began by acting, in a moment, quick as anything, you were serious and inside the skin of the song, mournful as midnight and feeling a black sort of ecstasy.’

My grandfather wrote, too, of ‘The Welsh being very Welsh, with memories as long as donkey’s ears’, and it is true that sometimes my own memory seems improbably long, irreconcilable with the Manhattan of 2008 where I reside. Every year it seems more impossible, illogical, that I should really have known, and known well, someone who fought in the First World War, who was actually born in 1896, born before even the motor car we both despise. And I bless that Welsh memory, as long as donkey’s ears, without any trace of English embarrassment, I bless it for ever.

Adrian Dannatt

CONGRATULATE THE DEVIL

In seven days I shall be killed, but I don’t know yet how it is going to happen. I cannot make up my mind whether to do it myself or to let those soldiers and policemen who surround this village do it for me. I shall probably toss up in the end and leave it to chance – if there is such a thing as chance. I don’t think about it much, but death takes a good deal of not thinking about. I try to forget, but now and then I find that I am pressing the artery at the wrist with my fingers, the way doctors do. The blood goes flip, flip, flip, like minnows rippling along. Then I lift my fingers and there is no flip. You are dead now, my boy, I say. The blood is still. So many flips for seven days and then no more.

That is as near as I can get to realising what death is. I doubt whether you will ever know how it happened. I shall tell you later whether it is to be by their lead or my steel (meaning the safety razor). The man who is in charge out there will wrap up these sheets and send them by special courier to the Home Secretary. He will hand them to the Prime Minister, who will pass them on to his wife, who wears the trousers. She will read them in bed for her amusement and talk them over, very discreetly, with Those who Count. There will be a small Cabinet committee with a very large blue pencil. If I decide on the razor blade, well and good; if on the bullet, my style is not so individual but that a line here and there cannot be rewritten.

You will have gathered by now that I am to die for reasons of state.

How did Stavisky die? The inner circle knows, but we don’t. Not so long ago, in a café-bar in Paris, I met a shabby down and out and gave him a drink. He begged for another. When that was finished he asked for another and we tossed up whether I should give it him. He won. He suggested yet another, but I said No, I was an Englishman, but not a fool. One more drink, he begged, and I will tell you something. I didn’t know what he meant, but I wasn’t going to miss anything by being mean over one drink. Perhaps he would tell me what to make out of life. I didn’t think he would, but you never know. I thought he was going to tell me about the girls in the quarter. That is information, too. Anyway, I gave him the drink.

When he had finished it I said: Well? He took me by the arm and we walked to the door. There he glanced around before putting his mouth to my ear. I shot Stavisky, he whispered, and ran. I asked the barmaid who he was. A bad character, she said, but he used to be a gendarme. And that is all I shall ever know. He didn’t ask for another drink, so I think he may have shot Stavisky. On the other hand, he took me to the door first, whispered it in my ear, and bolted. Perhaps he expected a boot in his bottom. If that was so, he didn’t shoot Stavisky. It matters little, but some day you may be handing out drinks at a London bar to a shabby ex-soldier, and wondering if what he tells you is true.

Why do I set myself this weary task? Partly it is because it will take my mind away from what is coming to me, but that is a small part of the reason. I write about this miracle of our days and the mess we made of it because I want you to see it from our point of view. You believe now that it was a dirty mixture of crime and hocus-pocus. That is what the newspapers have told you, not because they have been misleading you, but because they have known no better themselves. There was crime; there was hocus-pocus, but nevertheless this affair has not been what you have been told it was. See for yourselves, and judge.

I sit in this dusty upstairs room of the ‘Red Lion’ in a lonely Welsh village, writing and writing. It will go on for seven days and then I shall be dead, as dead as the noble browed man whose large sized photograph stares at me from over the mantelpiece. Who is he? I asked the round barrelled landlord. Thomas Charles of Bala, he replied, a very saintly man. Is he dead? I asked. Oh yes, a long time, but he was very saintly. I am not very saintly, but soon I shall have a great deal in common with him.

It began as a laughing matter, and those who have not lost their sense of humour over dogs (there are still a few) will be glad to know that it was a dog started it.

Mrs Marsham went to Vienna and parked her dog on my uncle, Colonel Starling, who had a ground floor flat in a big block at Hampstead. On an August afternoon Dobbs, the Colonel’s personal servant, took the dog for a walk up the High Street. Dobbs was middle aged, fat, and walked with a slow, waddling movement, like a duck at evening. It was a very hot day, and he had undone the three bottom buttons of his waistcoat. He wanted to get to the water at the top of the hill. It would be cooler up there.

Connected to Dobbs’ wrist by what looked like a very long thin brown snake was the dog, That There, a miserable specimen of his kind. Dobbs held that he was mentally deficient, and put it down to the fact that he had lived his life amongst women. ‘Like a brat.’ He was extraordinarily woolly-minded, mean-hearted, and contrary. ‘Can’t make up ’is mind fer two minutes together,’ said Dobbs. This afternoon he was going through the whole rich gamut of his deficiencies, stiffening his forelegs out in front of him, bunching back in an alarming manner and skidding along the pavement, his head twisted painfully to one side as if he were on a gibbet; giving that up and trotting with a whimpering docility at his master’s heels, nose unnaturally low, stricken with sin and unworthiness; and when he grew tired of that, which was often, getting himself into the gibbet position again and trying desperately hard to commit suicide. ‘Now ’e thinks ’isself a tug of war,’ swore Dobbs. ‘Does

’e ever think ’es a dawg? Does ’e ’ell. An’ is ’e right? ’E is.’ They came, by and by, to the Pond, the water, the sails, the children, and a breeze. Dobbs stood there for a time absorbing coolness. The Dog, being the kind of dog he was, turned his back mournfully and flattened his ears as the cars whizzed past.

Dobbs crossed the road towards the Heath, and stood for a moment at the pavement’s edge, looking with a townsman’s surprise at such foreign bodies as trees and green grass and blue skies. Then, with a little sigh (he had his duty to do by the dog) he stepped off the familiar asphalt into alien nature.

But the dog objected: fiercely. He had been brought up in ladies’ laps and drawing-rooms, fondled and dandled and kissed on the nose, and he hated all this tugging and hauling. He sat down with such a jerk that it looked as if he had finally succeeded in hanging himself. Dobbs swore and tugged so impetuously that the lead slipped off his wrist and snapped back at the dog’s nose. He jumped a clear foot into the air, and set off at a wild gallop over the grass.

‘Hi, you,’ shouted Dobbs, following at what speed he could and lifting his arms to the sky like a prophet. ‘Thinks ’es got an electric ’are in front of ’im nah,’ he panted. ‘Thinks ’es at the dawgs, no doubt. Stop ’im,’ he yelled to a group of children, but they only stared at the beast as it swung past, and even more eagerly at the fat man. Dobbs shook his fist at them. The dog, vanishing over a hillock, stopped, wagged his tail uproariously and set off again. The insulted Dobbs panted to the top of the mound to see his quarry doing a long tireless lope in the middle distance. ‘Hi,’ he shouted again, but half heartedly. ‘You wait till I get yer,’ he mumbled. ‘You wait.’

He undid the other buttons of his waistcoat and waddled off in the wake.

But the dog was not consecutive. He could keep nothing up for long. Dobbs was still a good two hundred yards behind when the dog stopped short in his flight and turned, crawling oddly, towards a man in brown sitting on the grass. ‘’Old ’im, Sir, ’old the devil,’ shouted Dobbs. Then slowly, getting his breath, buttoning up his waistcoat and mopping his brow, he waddled towards them.

‘Sits there easy as a statoo,’ he grumbled. ‘Sits like a peach on a plate, like he ’ad no legs to gallop on. Let ’im wait!’

The man in brown patted the dog’s flanks. ‘I’ve got him,’ he said.

‘Thank you, Sir,’ said Dobbs. ‘An’ as for you,’ turning to the dog, ‘I’ll see to you in the privacy of the ’ome.’

He sat on the grass and cooled himself by flapping his bowler fanwise in the air.

The man in brown offered him a cigarette. The old soldier touched the rim of his bowler in a military salute. ‘Name of Dobbs, Sir, and thank you,’ he said. ‘Name of Roper,’ grinned the stranger. They lit up. Dobbs rolled gently on to his back, tilted his hat over his eyes, and smoked into the air.

He fell asleep.

That is what Dobbs thought he did. That is what he told me he did when I talked to him about it. He must have fallen asleep, but there were dreams. He couldn’t remember the dreams but he knew they were uncomfortable. ‘Lying on me back in the sun. Nightmares,’ he mumbled to me. But he couldn’t remember a thing. If he could remember he’d tell me, honest, he would. He wasn’t hiding anything. There had been dreams, bad ones. But he could only sort of ... sort of ... it was like trying to remember in the morning what had happened when you had been very, very screwed the night before. It came at you and then went away before you could get your hand round it and hold it. ‘Now look, Dobbs,’ I said, ‘something funny happened then. You know something happened. I don’t believe you were asleep. And you don’t believe it yourself. Try and

remember.’

‘I can’t, Sir. Not a thing.’

‘He did something to the dog.’ ‘You think so, Sir?’

‘Look at what happened afterwards. Of course he did something to that dog.’

‘I didn’t see ’im do anything.’

‘Dobbs, you’re not the sort of man who falls asleep if you’ve got somebody to talk to. About this man. What was he like?’

‘’E ’ad a brown suit on, but no ’at. ’E was ugly as sin.

That’s all I can tell you.’

‘What do you mean, ugly as sin?’ Dobbs pondered.

‘’E ’ad knobs on ’is forehead. An’ a mouth, that wide.’ ‘Anything else? Old? Young?’

‘Youngish.’

‘You’ve got to remember, Dobbs. You probably talked about the Colonel. You’re always talking about the Colonel. You were talking about the Colonel when I was a boy. What about that little speech of yours: “A m I a Indian servant? I am not. Is it what the Colonel would like me ter be? Ah! Ah! An’ will I ever be one? Never, not whilst I’m Dobbs. ‘’Im with one foot in the grave, too!”’

Dobbs looked uncomfortable, but he shook his head dumbly.

‘“He expects you to salaam and touch yer forred and do the old kow tow,”’ I went on relentlessly. ‘ “An’ all fer twenty-five bloomin’ bob a week. But do I do it? Do I?” this is where you spit, Dobbs. “Catch me wiv a loin cloth round me little bottom.” You must have said that.’

Dobbs’ eyes wavered. He, too, knew his speeches off by heart.

‘The first thing I knows,’ said Dobbs, ‘is I was ...’

The first thing Dobbs knew was that he was running, the sweat cruising down his face, and that he had the dog clasped in his arms. He was a good two hundred yards away from the man in brown, and he couldn’t remember how he had got up and come that distance, how the dog had got into his arms, why he was running, or what his terror meant. He was trembling all over, and he couldn’t remember why. He had not the vaguest idea why. ‘I must a been asleep,’ he thought. Sleep walking. But even in his sleep he couldn’t think how he had come to pick up that piece of leprosy, That There, the dog. He promptly threw him to the ground, and walked rapidly towards the streets.

Funny he had fallen asleep, like that!

But everything was all right again, except, of course, for That There. That There was acting according to his nature. There was no way of knowing in advance what That There would do. Twice, during the short walk back to the flat, he had stood stock still in his tracks, which was usual enough, but he had then sat up like a beggar on his haunches, looking extremely miserable, and had rattled his teeth, scraping at them with a paw. It was something new even for him. But Dobbs wasn’t standing any nonsense from a dog, and on both occasions got him on the march again, double quick.

They were back at the flat about ten minutes to four, a ground floor flat. Dobbs slipped the dog loose in the drawing-room, and was busy for several minutes laying the Colonel’s tea on a low occasional table near the french window. He plugged in the electric kettle in the kitchen and cut a few thin slices of bread ready for the toaster. Then he went back to the drawing-room to wait for the Colonel. It was a minute or two to four, and the Colonel had said he would be back by four, prompt.

He waited, holding his head in his hands, elbows on the mantelpiece, wondering what had happened to him in the park. To wake up with That There in his arms! He lifted his head to see where the dog was now. It was crouched in the corner. Dobbs felt unaccountably miserable, closed his eyes and held his head in his hands. Four o’clock tinkled from the clock. The Colonel was going to be late. But he was too miserable to take advantage of it. He felt ... humble, and Dobbs, to whom humility was a new sensation, suspected that he was a bit off colour. ‘I ain’t feeling very well, seemingly,’ he mumbled, rubbing the back of his hand against his forehead. ‘Liver,’ he thought, remembering the Colonel’s diagnosis of all human ills. This must be liver.

Things were beginning to sideslip. He grasped the edge of the mantelpiece, but did not feel very secure even with the cold wood between the ball of his thumb and the fingers. There was a funny swaying feeling about his legs, like water-cress in a current....

‘It’s like as if ... as if ...’ he began thinking. ‘It’s like having one’s senses stole.’ His knees were wobbly as a jelly. There was no strength in them. If he didn’t look out he’d be measuring his length on the floor, going wallop. Sure thing, going wallop. Having your senses stole, that was it. He remembered a fellow in a loincloth in the bazaar who had done that to him in India, and he grew very suspicious. ‘I been got at,’ he said aloud. He was sure of that. He was having his senses stole. Something outside himself was doing things to him, getting at him, making water out of his thighs and knees and ankles and fair flooding his boots. He was clinging now to the mantelpiece, with both hands. The free born Briton in him rose in terrific protest. ‘Ah, would you now?’ he muttered. ‘Would you now?’ and he glared round the room. Old That There was still in his corner, but sitting upon his haunches, eyes bulging and glowing, his red slip of tongue hanging out of his mouth, all a grin from ear to ear. The moment he saw the dog’s eyes there was a tremendous increase in the wateriness about his knees. Jesus, he was awash, fair awash! It was That There was doing it. It was the dog was getting at him. Old That There....

But he rose into his right senses for a moment again. ‘I’m slippin’,’ he shouted or thought he shouted, and held on grimly to the mantelpiece. The wall was rolling in front of his eyes. He mustn’t let go. He must hold on. He mustn’t slip into the waters rising about him. He gave one wild last look at the dog, and the struggle was over. He let go. He wanted to. His hands opened, he turned round slowly, and dived headlong to the floor.

The Colonel was five minutes late, hurrying home through the heat, and he didn’t like being late. The army had given him the secret of time. You conquered it by sticking to it. Tea, he had told Dobbs, would be at four, and now it was five past four. As likely as not that very difficult man had served it up at four, prompt, to spite him, and now the tea would be cold, and the thin crisp slices of Austrian toast would be cold, and Dobbs would be looking at him as much as to say: Serve you right. If you say tea is at four tea is at four.

By the time he was letting himself into the hall of the flat there was quite a skirl of rising winds about the Colonel’s heart. Dobbs was impossible. He would order him at once to make fresh tea, fresh toast. Dobbs! he shouted from the hall. Dobbs! There was no answer. (A troop of Indian servants padded softly along the corridors of his brain, running, and that did not help matters.) It was Dobbs’ duty to be in the hall, to help him divest his coat, to take his hat and his gloves, to open the drawing-room door for him; and above all, to make him feel that he was being welcomed, attended to, fussed over. Not that Dobbs ever did that. But if the Colonel could not command love in his own home country (there had never been any difficulty about it in India) he could at least enforce the strict letter of the law. Dobbs! Dobbs!

There was no answer.

He must be gone. He had not only made the tea at four but gone out!

Was that a noise? Did that come from the flat?

Good God, this was going too far. Was Dobbs in there pretending he hadn’t heard?

Dobbs!

The Colonel took off his coat in a fluster, temper rising, threw it over a chair, flung his hat and gloves after it, opened the door briskly, and stepped in.

Ah, the dog. It must have been the dog he had heard. There was no one else there. Dobbs was either gone out or was hiding in one of the other rooms. The dog came bounding towards him, and he bent over to pat it on the head. But before the dog had quite come up to him the arm chair near the tea table was pushed to one side and a strange creature came galumphing across the floor. Dobbs! on his hands and knees, bounding and leaping in the most brazen, unhuman way possible! His tongue was hanging out; his eyes were liquid with joy and devotion, and he was shaking his bottom from side to side like a ... like a cinder sifter. And now he was making small piping noises in his throat like an animal, giving vent, indeed, to the same extravagant motions and whimperings that a dog does when it welcomes its master. Mixed with his shocked surprise there was a momentary triumph in the Colonel’s mind. This, after all, was the Dobbs he had always wanted; and this, the welcome home.

For about as long as it takes to count ten the Colonel felt and fought the emotions his batman had known by the mantelpiece; but he was stricken more quickly, so that at no time did he realise clearly what was happening to him. At one moment, there was the dog in front of him, wagging its tail; and there was Dobbs, going through the same parade in his clumsy, caricaturing human way. Then there was a rift of time filled with turbulent emotions, and the next instant he also had collapsed on his hands and knees and his own square-built rump had begun that self-same cinder-sifting motion.

But with a difference, naturally, the difference, even in this outlandish experience, between the well-bred and the vulgar, between Colonel and batman. Dobbs was behaving like an undisciplined mongrel, with zest and exuberance (he was now trying to scratch behind his right ear with his boot and not doing it very well). But the Colonel sank to earth as impressively as anything at the Dog Show, with a stiff, creaking dignity. He yawned a little and stretched out his hands on the carpet, laid his chin upon them, and closed one eye, keeping the other steadfastly on Dobbs, who was getting more and more heated over that right ear. The day was hot. The Colonel put out his tongue occasionally, and licked his chops before reverting to his Argus-eyed stance. It was very like Landseer’s Dignity and Impudence.

As for Impudence, it was impudence with a vengeance. There was that fellow Dobbs (who never had known his place), letting himself go, giving free vent to his abounding spirits, pretending to bite Dignity’s paws, launching himself at him in mock attacks, romping round him in circles, sitting up on his haunches, panting, tongue out, and never keeping still a moment. Jumping over Dignity’s back and stumbling at it, too. Now he was trotting over to the tea table, taking a piece of cake and eating it off the carpet. Now he was putting a playful paw on the Colonel’s head, rubbing against him and once more trying to clear his back. The Colonel had to snarl back at him and show his false fangs. The ridiculous Dobbs yapped about this, at a safe distance, for some time. The Colonel creaked on all fours over to the bookcase and subsided there with a slight clatter. Even Dobbs in time grew quieter and crouched down near the armchair, facing That There and gazing steadily into its eyes, only an occasional quiver and shake of the rump to show that he was ready for a game any time.

There was a restaurant attached to the block of flats. The Colonel took his meals there when he was not lunching or dining out. Because he was pernickety over his food the manager used to send one of the waitresses up to his flat to find out from Dobbs what his master fancied that day. The girl now rang the front door bell, but there was no answer. Knowing, however, that Dobbs sometimes left a note on the kitchen table, she let herself into the hall with a master key. The door of the drawing-room was ajar. Thinking that Dobbs might be there, or perhaps not thinking at all but following her pretty nose, the girl pushed the door wide and peeped through.

She was not a nervous young woman. She had served her apprenticeship in a boarding house and seen (for so young a creature) many strange sights, and what she hadn’t seen there she had seen on the films. But what met her eyes now was very much outside her experience, and when the Colonel lifted a regal head and licked at his moustaches, when both the real dog and that underdog, Dobbs, began bounding towards her, she let off a fine, piercing shriek and sprang back as if she were on the stage. But the next instant she too was down on all fours and advancing shyly into the room, looking extraordinarily graceful and young and attractive, blushing prettily, and moving with a kind of easy, sideways cavort. She was, in fact, so delicately reticent that Dobbs was only able to come up with her by pushing over a chair and doubling several times in his tracks. Being the kind of dog he was, he licked her nose half a dozen times and seemingly quite overcome by emotion, leapt into the air and went for a quick gallop round the room. Even the old Colonel paid his tribute to her youth and beauty by stalking in a finely courteous but non-committal manner across the floor, and after collapsing again, regarding her with grave approval from between his paws. It was as if one of the lions had come down from Nelson’s plinth and taken a solemn small walk.

There was electricity in the air, as the novelists say. And Dobbs was a good conductor. One does not know what might not have happened if the spell had remained unbroken. But broken it was. The waitress, fortunately for herself, perhaps, had left both the drawing-room door and the hall door open. The dog, frightened by the antics of these humans, scuttled off at a brisk pace towards freedom. At the very moment when it disappeared Dobbs was beginning a second and even more dashing series of licks. Suddenly he stopped, looked at the maid with surprise, looked at the Colonel, and scrambled to his feet. They gazed at one another, first with alarm, and then as the memory of their deeds crowded into their minds, with dismay. The girl looked reproachfully at Dobbs, burst into tears, and ran from the room. The Colonel rose slowly, stiff in every joint, and brushed the knees of his trousers. Then he caught his man’s eye, frowned automatically, mumbled something about tea, and with a cry asked for the dog.

Dobbs ran out into the hall, and came back again to say that it was not there. From the sitting-room window the Colonel looked up and down the street. ‘There he is,’ he said. Dobbs went to the window too, and looked out. The dog was stationed very deliberately at a lamp post across the road. Already, in both their minds, some vague perception of the dog’s responsibility had taken shape. Now, after looking at the dog, and looking at the lamp post, they looked at one another, and away again hastily.

There were things which had been spared them. ‘Shall I fetch it?’ asked Dobbs.

‘Not on your life,’ said the Colonel. ‘Get tea.’

Dobbs went at once, forgot even to remind him he was late. The kettle was boiling its head off. Nothing was said during tea time. The Colonel drank his tea and munched his toast without a word, glancing occasionally at the place he had occupied on the floor, and occasionally at the ceiling, which had stretched so high above his head and was now so low. It was not until Dobbs had lit his cigarette for him that he disposed of the matter, oracularly, once and for all.

‘That dog,’ said the Colonel, ‘was bewitched.’ ‘Yes, Sir,’ said Dobbs.

The last witch was burnt in England two hundred years ago. Neither Dobbs nor the Colonel believed in witchcraft.

The Colonel did not know in the least what he meant by saying that the dog was bewitched. Nor did Dobbs. But both of them found it an absolutely satisfactory explanation. It accounted for everything.

‘What happened to the girl?’ I asked Dobbs. ‘She gave notice, Sir.’

‘What, she’s gone?’

‘Well, Sir, I explained to her as ’ow the dog was bewitched, so that was all right. She’s still ’ere if you’d like to speak to ’er.’

‘And the dog? Did it get home?’

‘No Sir. It was run over rahnd the corner.’

And that, somehow, seemed proof positive that the dog had been bewitched.

I am very fond of England and the English people. I like them. I have travelled all round the world and never come across anything like them. We are Unique.