6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

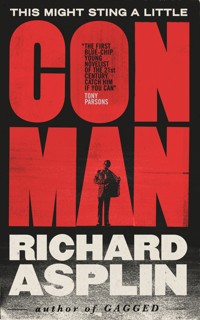

Conman is the story of Neil Martin, a kindly family man. Geeky and nerdy, if you met him, you would assume he runs a failing comic memorabilia store in London's Soho. Which he does. In order to bail himself out of a stock-ruining flood, he needs to claim on his insurance. Which he would do - if he'd remembered to pay for it. Terrified of losing everything - his wife, his daughter, his business and his home, Neil reluctantly agrees to let Christopher - a passing hustler - use his premises for a big sting. So the con is on and the trap is set. Neil meets Christopher's crew and, as he introduces them to the world of vintage comic collectables, he is introduced to the life of the grifter: swaps, swindles and switcheroos, the colourful patter of marks, mitt fitters, cacklebladders and cold pokes. But things are never as they seem in the twilight world of the confidence man. And when Christopher's real target is revealed, Neil finds himself plotting, switching, swapping and scamming for revenge, for redemption, and for his life. Somewhere in the shadows, where High Fidelity meets The Usual Suspects, where David Mamet meets Ben Elton, Conman will keep you laughing, guessing and up all night until the last page is turned and the breathtaking truth is revealed.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2009

Ähnliche

www.noexit.co.uk/conman

For Neal, who’ll enjoy this one and Luthfa, without whom nobody would be reading this. Love to you both.

Contents

Title PageDedicationpart onenowthenonetwothreefourfivesixseveneightnineteneleventwelvethirteenpart twofourteenfifteensixteenseventeeneighteennineteentwentytwenty-onetwenty-twotwenty-threetwenty-fourpart threetwenty-fivetwenty-sixtwenty-seventwenty-eighttwenty-ninethirtynowACKNOWLEDGMENTOTHER TITLES BY THE SAME AUTHORCopyright

part one

now

“Wait, is this a con? Is that what this is? Are you … are you trying the old switcheroo with me? Trying to pull wool over my leg? … You swear? Because let me tell you right now Mr Cheng, I’ve had exactly my legal limit of swindlers, marks, mitt fitters, cacklebladders and cold pokes. Up to the brim, you understand? Enough to last my family and me a long time. To last us the twenty years I’m going to have to spend in prison if I don’t get the thing back, in fact … Yes, prison Mr Cheng. Big grey building? Nestling among ten acres of beautiful rolling concrete? Conveniently situated for group showers and buggery, ideal for the first time offender … ? Well it’s where they put husbands like me. Idiot husbands who … Look, look forget it, just give me a price to have it back. A proper price. And don’t try and jerk the fleece behind my back. How much?”

Look, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to come back in here disturbing you. It’s just the police said … and it’s a bad line and it’s … Sheesh, bad day, bad line. Bad from the beginning. From forever. I won’t be long. I’ll get out of your hair. You get back to your drink. Ignore me. Really, I’m sorry.

“What? But you only paid … No way? Redford and Newman? Nobody gets Newman. The guy’s a hundred and sixty years old, wired up to an intravenous bottle of spaghetti sauce in Beverly Hills … Swear? … Lord. Okay okay, but c’mon Mr Cheng, please. You gotta do me a better price. My daughter … there’ll be lawyers. Lawyers. They’ll say I … God. C’mon, it’s me, Mr Cheng. Please?”

Woahh, sorry, sorry. Oh look, I spilt your drink all over – let me – barman? – let me get you another. Sorry. It’s just this guy on the phone, he’s got my life in his hands and the police told me to … oh it’s too complicated to explain. Barman? Whatever my friend here is having.

“Look Cheng, haven’t you been listening? I don’t have that kind of money … Well, I-I’m suggesting you lend the thing to me. Just for a day or so. An hour even. The police said I needed … Yes, the police. Where do think I’ve been for the last … Well when’s your buyer coming? … Oh for Chrissakes, three hours? … No, I keep telling you, I can’t, I don’t have it. Look I beg you, promise me you won’t sell it … Earl’s Court, I’m in Earl’s Court. A pub. The World or The Map or something …”

Huh? Atlas? Oh, oh thanks. Thanks my friend. How’s your drink? Look, I’m sorry about the yelling. It’s just … well as you can see from the suit, it’s been quite a day. This? I dunno. Corn syrup I think. I know, I know, it stinks. Hell, I didn’t get any on your … ? Okay. Again, I apologise.

“Cheng? My friend here says it’s The Atlas. Earl’s Court … No, round the corner from there. Look, give me three hours. I’ll come up with something. I have to. Jane’s dad is saying she’ll … God, just promise me you’ll stall your … Fine. Three hours.”

God. What am I going to do? Three hours. So that’s …

Right. Of course. Great.

Excuse me? Hi, sorry to bother you again. My watch is … well it’s … long story. Do you know what time it is?

Already?

Okay okay. Right. Calm. Don’t panic. That gives me …

Christ.

Do you know if there’s a bank or anything around here? Pawn shop maybe? Somewhere I can sell … I don’t know, a lung or something? What’s a lung worth? You want to buy a lung? A kidney? How are you for kidneys?

Hn? Sorry, I know, I’m in a bit of a … I’ve had a …

Oh no, no I couldn’t, I don’t want to intrude on your –

Oh that’s kind, you’re very kind, thank you. You don’t have a tissue, do you? My nose is beginning to …

Thanks.

Man. What time did you say – ?

God. Where’s that phone. Let me … let me try her again. Sorry. I’ll just be … I need to make a …

“Hello Jane, I – ? Edward please. I need to talk to … Because I’m her husband and I love her and I need to explain. We’re a family, I would never … I can, I can prove I didn’t … well no, but – in a few hours. I’m trying to … Please Edward, tell her …”

Christ.

“Tell her she … she is everything to me. Everything. You understand? She’s why I get up in the morning. She’s the whole point. Her and Lana. They’re the whole point. They’re all I have. Forget the rest. Forget the shop. That’s not who I am. They are who I am. My family is who I am. You take them away from me and I have nothing. Nothing. And … and tell her if she goes and she takes our daughter I might as well be guilty of everything they say I’ve done because then I’m in prison for life anyway. You tell her that. Edward? Edward, are you – ? Edward?”

Great.

I’m sorry. You don’t have to –

Well thank you. Thank you, that’s very kind.

God look at my shirt, this syrup’s getting all over the place. I’m gonna take my jacket off, put it on the … oh God it’s everywhere. Gaah, my lighter’s all sticky. My cigarettes. All my pockets … God it’s all over the letters, damn. Sorry, can you hold … thanks.

How? Oh you don’t want to know. No really, enjoy your drink. I’ll just …

Man. Man oh man.

And look at this place. Look at it. It’s like nothing ever happened. The bar, the tables. Like they were never here.

Hell, maybe they were never here? Maybe it’s me? Maybe I’m losing –

Letters? Oh. You’re still … Thanks, sorry, my mind’s all …

From? What these? Ha. From indeed. Her name’s … God she was right, they even smell like her. Go on, sniff the … see? Clever touch. And look, even the postmarks – oh you can’t see, they’re covered in this damned syrup. God it’s everywhere. My matches, my notebook … Anyway, trust me. Postmarks. Six months ago. Four months ago. Here, this one? Three weeks ago? Clever clever clever.

In fact, you want clever? Let me read you … No I insist, here we go, you listen to this. You won’t believe it.

“… and the more I think about your words Neil …”

Oh, that’s me. Neil Martin. How do you … oh, sorry. It’s just syrup, it’ll scrub off. Sorry.

Anyway –

“… the more I think about your words Neil, the more I feel the same. Just thinking of you gives me a sick ache inside. A painful teenage ache. Because that’s how it feels when we’re apart, Neil. Painful because I imagine you with her and I know I have to wait so long until I can see you again …”

And so it goes on. Pages and pages.

Oh you don’t want to know. Just hope you never meet her. Don’t meet her or anyone like her. And don’t … don’t lie to the only person you ever truly loved, either. Don’t ever do that.

I’m rambling. I know, I’m sorry. I’m a bit … Jus

t tell them the truth. I mean it. Tell them everything. Tell them you love them. Show them you love them. Every day. Don’t let it … don’t let it in. Don’t let it start. Do the right thing. Do the good thing.

Oh, and balance your chequebook every month.

I know, I know, it sounds …

But I mean it. Every month. Cheques and balances. Keep on top of it. And plumbing too. Hell, don’t neglect your plumbing.

That’s how it can start.

Or at least, that’s how it all started for me.

All … all this.

Plumbing. And a cheque. Writing a very small cheque.

Or rather, wishing I had.

God, I really wish I had.

then

one

With a deep breath, I flipped back through the stubs, reading out loud to the room like a teacher at registration.

“Okay okay. Let’s not … let’s not panic. C’mon now. Visa bill. Next bill. Road Tax …”

Dionne Warwick warbled from the stereo, goading me to take it easy on myself. Fat chance.

“… vet bill, Mastercard, Jane’s Visa. If you have not yet received a new cheque book …”

I flapped it shut and a little more panic squirted into my stomach.

It wasn’t there.

Not that I really expected it to be there. It wasn’t the chequebook for the business account and it hadn’t been there the first six times I’d checked it. But it was my last hope. A clutched straw at the bottom of an over-scraped barrel on the beach at Last Resort.

Throat tight, I chewed the inside of my cheek, trying to keep my gaze from the corner of the desk. From catching the eyes of the two beautiful female faces smiling from behind the glass of a silver photo frame.

Shit, I thought.

The cat wandered into the lounge idly across the Easiklip flooring and sat on the rug, looking up at me. I swivelled around in my creaky chair to look at him straight.

“Did you pay it?” I asked. “Please. Tell me you paid it?”

Streaky remained silent, but his look said he would have paid it if he’d been asked to. Because he wasn’t the sort of forgetful cretin who’d put his whole family and future at risk. He started washing his bottom.

Trying to keep a lid on the fear, I swallowed hard, turned the photo-frame face down and began to wade purposefully through the paperwork on the desk for the hundredth time. Letters from the bank, from solicitors, trade fairs. It would be here. I must have paid. I must have. I’m not an idiot.

But what started as a purposeful wade collapsed quickly into a despairing yowl as an unquestionable fact arrived, dropped two leaden suitcases and took up permanent residence in my bowels.

I was an idiot. I hadn’t paid it.

I got up itchily and clicked off Dionne because I don’t know about you, but I like to choose a CD to fit a mood, and Bacharach just isn’t panicking sort of music. I let the small flat sit in a brooding silence for a long while. Of course, the cat might have called it a peaceful silence, or a tranquil silence.

But then the cat didn’t know what I knew.

Loose knees shaky, I wobbled into the kitchen to distract myself with tea. Blu-tacked to the kettle’s smudgy surface was a small pink cardboard star with ‘£2’ printed on it. I blinked and it vanished.

Easy there, Neil. Easy.

I jumped at the sound of the phone in the lounge. Our nice phone. White bakelite. Heavy, with a proper circular dial and a real ringgggg to it.

I stood listening to the real ringgggg for a moment. Hating it. I’d gone off the phone recently. I preferred letters. Letters I could ignore more easily.

Ringgggg.

I moved back into the lounge, past the couch that had a blue cardboard star on its arm, proclaiming “£50 o.n.o.” and hauled up the receiver.

Bedlam. A party. Laughter. Music.

“Hello?” I said. More music and laughter. Some people clearly not doing their accounts. Or at least, not doing mine. “Hello?”

“Heyyy, is Franny there? Francesca?” Laugh, shout, thud.

“No. No there’s no-one here of that name. I think you have the wrong –”

“Is that Mike?” Thuddy guffaw shout.

“No. There’s no Mike and no Francesca. You have the wrong –”

He hung up, so I did too.

I blinked a few times. The small ‘£5’ sticker on the telephone dial didn’t move. I blinked harder. That got it.

I sat on the £50 couch and dragged worried eyes about the lounge.

This mental car-boot pricing, working out what I was going to end up selling everything for, had begun recently. Ever since the firm of Boatman, Beevers and Boatman, EC3 had written to me asking about the cheque. Their first letters I’d ignored. The next few I’d fobbed off. Brief responses about ‘pending payments’ and ‘full recompense in due course’.

But they kept coming. Each one leaning a little harder, pressing a little further, like an escalating bar-room threat. “… Dear Mr Martin, please be informed that unless contact is made with this office by Friday, November 6th, we will have no choice but to take legal action …”

Yeah?

Yeahhhhh.

I was halfway back to my kettle, mentally breaking down the next ten days into a workable rota of self-loathing and deceit when there was a scream.

But a real scream. A terrifying, throat-tearing scream.

Palms cold, I bounded over the cat and back into the lounge. There was a rev of un-tuned engine and squeal of tread-less tyres. I whipped open the curtain.

She was on her knees, face in shadow, bathed in the UFO glow of the yellow street lamp, a crunch of broken glass lying like spilt diamonds about her. The light from my window must have caught her eye because she turned to face me, face torn with anger.

“The police!” she bellowed. “Get the police!”

Heart thundering, I heaved up the bakelite, whirring the nines and clamping it under my ear. As I was connected, I craned a look back out onto the dark street. She was stumbling to her feet, one shoe off, leaning on our wall for support, whirling her bag like a slingshot and yelling into the night.

“Go on! Take it! Take it! Kill yourselves, you dickless fuckers! Wrap it round a postbox. Very rock and roll. Very in the hood!”

“Police emergency,” the phone crackled.

“Hi yes yes, a woman has been attacked, or carjacked I think.”

“Two killed!” the woman bellowed up the street, kicking and whirling. “Two killed in nine-year-old Honda Civic on the Upper Richmond Road! Oh very Tupac. Very P fucking Diddy!”

The policeman took the details and said officers would be there soon, so I hung up and hurried down into the cold blast of the street. Lights were clicking on in the Georgian mansion block opposite, nets twitching as local residents felt the tremor of their property values dropping. The woman was slumped against my wheelie bin with her bag at her feet, breathing deep, shaking.

“I’ve called the police. They’re on their way. You all right?” I jittered, heart thumping.

Gathering her thoughts and cigarettes, she eventually eased herself up. She had a nasty graze on her temple and three thick waterfalls of dark red hair had come unclipped from an evening-out arrangement, tumbling lazily over her face and shoulders. Her dark cocktail dress was now sequinned with pavement grit. She pushed her hair aside, revealing a striking pair of dark brown eyes.

“Bastards,” she sighed eventually. “You got a light?”

“Uhmm, I-I’ve got tea?”

“Any vodka you can stick in that?”

“Er y-yes I should be able to find some. Come on in. God, you all right? What happened?”

“Put a lot of vodka in,” she said, leading the way up the scruffy steps. It really was a very short cocktail dress. “Don’t worry if the tea won’t fit in there with it. And grab my other shoe could you?”

Head tumbling, I watched her disappear inside the flat and then scurried about on the pavement for a moment, eventually retrieving a dark brown velvet stiletto from the kerb and hurrying in after her.

“Groovy place. What do you do, collect this stuff?”

Her name was Laura. She sat on the couch, breathing deep. Nervous chit-chat, calming herself down. Her other shoe was off now, painted stockinged toes curling anxiously on the edges of the rug. The first vodka I’d fetched hadn’t even touched the sides so I’d fixed her another. I drank tea and the cat watched her from the footstool as she lit up a shaky cigarette, taking long and slow draws, peering about the room.

“I guess so,” I said, handing her a chipped saucer as a makeshift ashtray. “It’s my job.”

Laura peered about the geek-chic walls. The posters, prints and props.

“Superman, huh?” she said. Understandably I suppose, as the Man of Steel’s iconic, brick-chinned visage was present a little too often in frames and figurines about the room. Not to mention his proud, hands-on-hips stance on my t-shirt. Laura exhaled a cloud of blue smoke and blinked at me from behind her hair. “This a gay thing?”

I coughed a little into my tea, getting it up my nose a bit while Laura took another shaky suck on her Lucky Strike and apologised, licking her lips.

“Sorry,” she said. “Nervous. Stupid. I’m a bit rattled. After …” and she motioned at the window. “Forgive me, I didn’t …”

“No of course, fine fine,” I repaired. “You’re not the first. I suppose it’s all a little camp. But no. It’s a … father-figure thing. Rather a clumsy one at that.”

“Father figure?”

“Long story. It’s turned into a sort of hobby anyway. Just the rarer stuff,” I said, trying to sound as heterosexual and un-geeky as I possibly could from within a fitted tee and beneath a cheap framed print of Christopher Reeve. “How are you feeling though? Anyone you want to call?”

“I’ll use your bathroom I think,” she said and wobbled to her feet, hoisting her bag. I led her down the hall, through the narrow gallery of comic book covers and clip-framed movie stills and fetched her a towel.

The police arrived while she cleaned herself up. Two huge guys – one young Manc constable and one old Scottish Sergeant – thudding up the stairs, waterproof jackets rustling. I sat them down and made more tea, leaving them to worry the cat and sniff at all my Clark Kents.

Moments later, carrying a tea tray through, I met a fresh-faced Laura coming down the hall, zipping up her bag and coughing a lungful of acrid cosmetic tang.

“Knocked off a bottle of something in your bathroom,” her voice said through the stinging cloud. “Bit of a stink I’m afraid.”

I not-to-worry-ed, blinking back the stinging tears and gave her to Scot and Manc for their questions. The officers were clearly taken with her, that much was obvious, both talking at the same time, interrupting each other, trying the old ‘sexy cop – sexy cop’ routine.

I meanwhile fussed with spoons and coasters like a Jewish mother, dropping enough eaves to pick up a bit of background. Laura was thirty-four years old. She worked in a sandwich bar on Old Compton Street in Soho. She lived alone. She’d been heading out to a party. Yes, it was her car. A Honda. Yes, it was insured. No, she didn’t get much of a look at her attackers. Yes she was shaken but not hurt. An ambulance wouldn’t be necessary. No, she’d never met me before and yes, black with no sugar would be fine.

She took a mug from me and mouthed a silent thank you from her dark painted lips and I suddenly found myself momentarily joining the policemen in the gut-sucking-in.

Hell, not that I want you to get the wrong idea about my marriage. Jane and I are –

Were –

Well Jane and I. It’s a happy marriage. Hand on heart. Other women, one-nighters, whatever. It’s never really been on my radar. I’m a family man. Have been since always. A beautiful wife and the cutest baby daughter. Enough woman for me.

My gut-suck act was something else. A symptom. A defence. I’m a blusher, you see. A stutterer. With women. Talk too much, don’t talk enough. Hopeless, always have been.

Luckily, Jane rescued me from a lifetime of bachelor bumbling by taking the lead at University. She brought me out of my sappy self one common-room afternoon, interrupting my reading with a drunken rant about how Batman wasn’t a proper superhero. Bashful or not, this was home turf so I wasn’t about to have that and we went toe-to-toe over strength vs powers for the better part of the evening. She knew her stuff and I knew mine and the rest sort of just fell into place.

She still won’t have a picture of Batman in the house, so I have to keep my – numerous – Dark Knights in the shop office.

Now you can get all Freudy on my ass if you wish. We can tire the moon with whether I’ve ended up surrounding myself with a houseful of macho superheroes in body-stockings and scarlet cod-pieces because I’m no good around women. Or we can go the other way and say that I’m no good around women due to spending all day selling comic and movie junk and developing no conversational skills beyond eBay and Kryptonite.

I’ll take either of those bets, no problem. A bit of both I expect.

What I do know is that if Jane hadn’t stepped up and thrown down a beer-fuelled Bat-Gauntlet and my best friend Andrew Benjamin hadn’t sat me down and given me a good talking to I’d be a lot worse than I am now. A woman like Laura would have had me snapping into a foetal position and dribbling. Fortunately for my gut, she didn’t stay much longer. The cops gave her a crime number and they left. She waived a lift home, which left her sitting on the edge of my £50 couch staring into an empty mug.

“So,” I began, easing myself into the armchair opposite. “Old Compton Street, you said? Just round the corner from me. Brigstock Place. Heroes Incorporated?”

Laura reached into her bag and started up another cigarette, her face glowing in the flickering match light.

“Missed that one,” she said.

“Most people do,” I sighed. “Not that it’ll be there much longer …”

“No?”

“It’s in a little trouble. A lot of trouble.” I glanced over at the desktop of paperwork, my stomach tumbling. “Sorry, you’ve been through enough. I don’t know why I’m –”

“Because you helped me out. C’mon, fair’s fair.” I looked back at her. Laura had sat back and crossed her legs, arching a stockinged foot. “Go on, get it off your chest. Trouble?”

My eyes lingered on her legs for an idle moment, before snapping back to my teacup.

“Well, there’s a convention coming up next month. Earl’s Court?” I got up and fetched a slithery flyer from the desk and handed it to her. “Mostly trade. I’m meant to have a stall. Me and this other guy, Maurice. Posters, autographs …”

Of course, Laura’s eyes began to glaze over, much like yours are now.

Really, it’s fine. It’s not your problem and not that interesting. So I took the hint and took her cup and she got her coat. She gave me a thank-you kiss that, either accidentally or on purpose, landed a little too near my right ear.

And then she left.

I offered her a cab or a lift but she wasn’t interested. Said she’d stick out a thumb. I went to the window and cracked it open to clear the stale cigarette smoke. I watched her sashay down the steps into the October night, light a cigarette and walk away up the street, heels clicking to the metronome of her hips until the trees took her from view.

I shut the curtains.

“We’re baa-ack!” Jane called up half an hour later with a slam of the door. She began to thud up the stairs with bags and squeaky toys and, I presumed, our precious daughter somewhere about her person. “There’s glass all over the pavement out there.”

“Tell me about it,” I called down, quickly creeping back to the lounge to shove letters into a box file, bury statements in my satchel and return silver frames on desks to the upright position. “What news from your dad?”

“Ooh big,” she said. There was the static crackle as she peeled off her jacket and the tinkle of hangers in the hall cupboard. “You won’t believe what he’s done. Where are you?”

“In here,” I said, heart thudding. I buckled my bag and slid it discreetly under the desk, stepping back quickly to view the crime scene.

“Dad has an accountant at Chandler Dufford … God what’s that smell? Is that cigarettes? Has someone … ? Wait, and perfume?”

“Daddy had a stinky drama while you two were out. Didn’t he? Didn’t he? Yes he did.”

Jane and I kissed softly in a cloud of warm milk baby smell, Lana strapped to her chest, her wide blue eyes swimming in and out of focus, watching her parents. I held them both for a moment, my family, swallowing hard, trying to bury the nagging stir in my stomach. Jane’s soft blonde bob, shampooey and clean and familiar against my cheek made my head swim. A deep breath and I broke painfully away.

“Drama?”

I gave Jane the bullet points, following her like a puppy as she unpacked, unhooking Lana and unrolling the blankie out on the floor. Jane was in clumpy Timberland boots, her favourite faded Levis and my dark blue fleece. She rolled the sleeves revealing her smooth pale arms and I watched as she set our tiny daughter down, blowing raspberries on her soft tummy.

“Upshot is, she broke a bottle of your perfume in the bathroom? A Chanel one I think?”

“Didn’t know I had any Chanel,” Jane said, getting up and curling into an armchair. “But she got away all right? She wasn’t hurt? The police gave her a lift did they?

“She said she was fine. I offered her a cab, but she just left.”

“You just let her leave?” Jane said. “She was probably in shock.”

“What was I going to do? Restrain her? She wanted to go, I let her go.”

Jane conceded with a shrug. I moved everything along and asked about her father’s news.

“He wants to start a trust fund for Lana. For her education. I had lunch with Catherine and she said Jack’s father had done the same for them when they had little Oscar.” Jane’s eyes shone.

“Trust – ?”

“An investment. I don’t know the details. He wants to pay for her school. Someone from his accountants is going to come and see us to explain it all. What do you think?”

The room went noticeably quiet. I waited for Jane to look up at me.

“Pay for her school?” I said.

“Oh Neil, let’s not –”

“Why does it need paying for?”

“Neil, I was a boarder from the age of eight,” Jane said. “I turned out all –”

“This is another of his ways of saying I can’t provide for my family, of course.”

“No, this is a gift. It’s what daddies do.”

“It’s not what my daddy does.”

“Well your …” Jane let that one trail off. The usual awkwardness descended for a moment. Jane pushed on to cover it. “Okay, it’s what daddies do where I came from,” she said. “And where I come from is part of who Lana is. Grampsy did it for me, great grampsy did it for mummy –”

And off she went down the bloodline, from stately home to stately home like a hyperactive National Trust guide.

Jane has the oddest relationship to her heritage. Most of the time she finds it hugely embarrassing and covers it all with dropped aitches, Doc Martens and faded Tank Girl t-shirts. But once in a while – which I rarely tire of teasing her about – it all boils over and she goes completely St Trinians. Times like now.

I tried not to listen, trying to concentrate instead on the focus of all this debate – Lana’s gummy wet smile and tiny jerking fists, podgy limbs like plump haggis in brushed cotton skins. I didn’t last very long. Certain phrases have a knack of jerking one back to attention.

“Sorry?” I interrupted, catching my fear and swallowing it hard.

“The shop too,” Jane said again. “Next week some time. We have to call and make an appointment. He’ll bring all the spreadsheets and such. Greg somebody,” and she rose, moving to her bag. “Dad gave me his card.”

“The shop too?” I wobbled. My world, so I suppose to one extent or another, the world, lurched to a stop. My mouth dried up, eyes flicking guiltily to my satchel. “He’s not going to want to spend all evening trawling through the shop stuff as well?”

“Well, dad said it couldn’t hurt to show him the lot. Apparently there are tax write-offs for the shop dad doesn’t think you’re taking advantage of. It would help this chap to know the whole … ah, here we go,” and Jane handed me a thick business card. Chandler Dufford Lebrecht – Wealth Management, followed by some city address. Jane lifted Lana from her blankie and curled themselves into the couch. “Did your Chanel woman stop you getting your accounts done?”

The sweet perfume sting was still hanging about the flat like a drunk guest.

“Huh? Oh I got a good chunk sorted. And what do you mean, my woman? She was in trouble. What was I meant to –”

“And your letter? Did you finish … y’know?”

The room fell quiet.

“To my dad?” I said, a little loudly. “You can say it you know. He isn’t Macbeth.”

“Sorry,” Jane said. “I know. It’s just …” and she fussed with Lana’s babygro. “And I’m sorry before, about –”

“It’s fine, it’s fine,” I waved. “And no, another page or so. I’ll post it tomorrow.”

“And have you – oof! Who’s a big girl? – Have you written back to that solicitors yet?” Jane added, holding the baby aloft, nose to nose. “Boaters or whatever they’re called? Told them you’ve sent a cheque? Aww, ooze a dribbly one den? Eh? Ooze a dribble?”

“Cheque? Oh yes yes, that’s … that’s all sorted.”

“Would you love me if we were poor?” I asked quietly.

I was propped up in the yellow glow of our bedside lamp, listening to the pages of Jane’s Terry Pratchett turn slowly and the clicky milk breath of Lana between us.

“Poor? What do you mean?”

“If something happened?”

“Like what?”

“Forget it,” I said. “It doesn’t matter. Go back to your book, I’m being … forget it.”

I sighed and stared at the ceiling some more. There was a beige half-moon of damp along the cornicing. A water tank leak that never really got sorted properly. Thoughts wobbled and worried like loose teeth.

“Oh, before I forget,” Jane said, making me jump a little. “Dad’s popping down to Brighton for a charity something or other next week. I said you’d pick him up from Victoria? Neil?”

“I mean, I know this place isn’t what your father wants for you.”

“Neil?”

“Hn? Yes yes, fine. And I know how he feels about me and the shop and everything.”

“We’ve been over this,” Jane whispered, shifting over towards me, snaking a scented, moisturised hand up to my cheek and giving me a long kiss. She broke away slowly with a smile. “You’re providing for your family. Putting a roof over our heads. He respects that. Just do what I do and ignore all that other stuff. That’s just daddy being daddy.”

“Not easy to ignore when he’s coughing up school fees.”

“Oh let him do it,” Jane soothed gently, giving my hand a squeeze. “He’ll write a cheque and it’ll be off his mind.”

The world lurched.

I stopped breathing. I waited. Swallowed hard. An idea barged in-between us, all fat arse and elbows.

I waited some more. The idea jabbed me in the kidneys and coughed.

“How er … much?” I said, too loudly and too quickly. I fussed with Lana and the duvet a bit to cover my eagerness.

“The fees? Fifty thousand pounds,” Jane said. “Greg thingy will bring a banker’s draft or something with him tomorrow I expect. Oh and while I remember, Catherine and Jack are coming over for dinner next Thursday.”

“Fifty? I-I mean, sorry, Thursday?”

“Next Thursday. Guy Fawkes. I’ll do a Nigel Slater or something. We can watch the fireworks from the window.” Jane turned and noticed the open book in my lap. “What’re you looking up there?”

“Looking? Oh er nothing, nothing. Just work.” On the duvet lay a greasily thumbed and well-worn comic-book price guide. Robert Overstreet’s. 35th edition, cracked open near the front as casually as I could manage, considering it had 900 pages and weighed more than I did.

“What’s it worth?” Jane asked.

“What?”

“C’mon. It must be in there. Has it gone up?”

“Oh,” I faked. “Same as ever I expect.”

“Dad thinks you’ve forgotten about it. His bank said you haven’t been to see it for ages.”

“Keeping tabs on me now is he?” I said.

I kissed Lana on the upper arm, kissed Jane softly on her toothpasty lips and then tugged the duvet about my chin and had a good long stare at the damp patch on the ceiling.

I thought about the box file above the desk. The contents of my battered satchel.

“Does he have to come over this week?” I said after a moment. “This Greg guy? Can’t he just send us the money to put away?”

“Dad said it’s more complicated than that. Plus he’s having a look at the shop accounts too, don’t forget? Free expert advice? You’ll have to bring the books home. I thought you’d be keen.”

“Mnn,” I said.

After a thoughtful moment I clicked on the bedside light again, shimmied up the bed and hauled Overstreet from the bedside cabinet. I flipped back open to the Golden Age comic listings.

1938 to 1945.

I chewed my lip. I thought about Jane’s father. I chewed my lip some more.

“Hey.” An elbow in the ribs. Jane.

“Sorry?” She’d said something. I’d been miles away.

“I said we’d love you no matter what,” Jane repeated, stroking Lana’s arm. “You take care of us.”

“Right,” I said, taking one last yearning look before slapping the book closed and returning it to the bedside. I clicked off the light once again.

An hour later, Jane and Lana both breathing beside me in the dark, I must have finally fallen asleep because I remember the dream. The Man of SteelTM, in handcuffs, heaving a huge, brown velvet chequebook over his head in glorious technicolour, the planet Krypton exploding above, taking his family away.

Forever.

Freud or not, I was in deep shit.

two

Now.

You might be wondering how my beloved wife came to know about Messrs Boatman Beevers and Boatman, what with all my deskbound subterfuge and satchel stealth? Or you may alternatively be asking yourself why I bothered with all the subterfuge and stealth when my wife already appeared to be up to speed with all things solicitor-like?

Well we’ll get to that. We’ll get to a fortnight ago’s surprise second post. The heavy paper, watermark and the City of London address. The letter that should have arrived safely at the shop where I could have disguised it among the other, shall we say, less immediate daily post:

“Dear Hero Incorporation, I picked up a Donatello Mutant Turtle Ninja at a boot sale for sixty pee. He’s got one hand, made in Korea on his foot (claw?) and his shell has got you are a gaylord written on it in face paints. My mates think it could be worth a hundred quid.”

It was the next day, Wednesday, 28 October, the day after the car-jacking, just after ten a.m. by the shop clock – a cracked plastic thing with Elvis Presley’s sneery mush on it. Sneery in the way that we’d all be I suppose if we had a layer of dust on our face and two clock hands stuck to our nose.

I had a Best of John Williams on the dusty stereo, the theme from Star Wars rupputy-pumping tinnily from one working speaker, soggy trouser bottoms and the rest of the post worrying me on the cluttered desk.

I’d had one customer already, a regular. He popped in most Wednesdays to tell me yes, he’d have a coffee if I was having one, sniff through any new posters that’d come in, do a crossword clue in my Empire magazine and challenge me to a game from the shelf. Downfall, Kerplunk, maybe a quick buzz at Operation. I kept a few faded dusty ones around to kill time with my few more intense regulars. It meant I had to sit uncomfortably close to them of course, smelling their lozenge breath and listening to their phlegm rattle, but on the plus side it meant I got a half hour’s silence without them whittering obsessively on about Bruces Banner, Lee, Wayne and Willis.

The day would pick up of course. As the hands of the clock swept Presley’s quiff from his eyes, Mr Cheng would come and press his nose against the glass as always. But until then, I had just the post to worry me, which it was doing a very good job of.

I filed the Teenage Mutant Ninja Timewaster in the bin along with the other three or four handwritten missives, mostly requests from private collectors for me to either take dusty rubbish off their hands or supply more dusty rubbish for them to annoy their wives with. Of the three ominous A4 envelopes, one turned out to be from the Earl’s Court Exhibition Centre: my contract, a detailed map pointing out Stall 116, Loading Bay C, set-ups times and so on, which I filed away for next month.

The other two – both solemn-looking buff things addressed to Mr Martin, c/o Heroes Inc – had me nauseous with nerves, an apprehension not entirely helped by the sick smell of rotten pulp floating up the cellar steps and John Williams who, having ra-pah-pah-pummed through Star Wars, was now sawing away ominously at the theme from Jaws.

I was just thinking that I might let the envelopes wait a while and go and have another coffee when, with a ting of the bell and a well hey there, one unexpectedly arrived.

“And what’s that monstrosity worth?” she said, motioning at the wall behind the desk.

“Monstrosity? That, I’ll have you know, is the first original poster I ever owned. UK quad, cost me fifteen pounds. Had it on my wall at college. An absolute classic.”

“Never seen it,” Laura shrugged, unloading her tray of coffee and a shiny bag of buns and croissants.

Thankfully for my nerves, she was out of the cocktail dress and into work gear, but even that she managed to carry off with a moll’s worth of 40s’ vintage sass. She had a thin, flowery top on, low cut in a sheer material, her small white brassiere just visible through the fabric. A thick red belt with a large buckle beneath and a thin black pencil skirt. The heels were gone, replaced by small school plimsolls, the whole thing wrapped in one of those huge dark green coats with the furry hoods. She had her hair pulled back and piled high, but one thick glossy tousle fell across her face. The graze on her temple had faded to pink. Somehow, however, even decked out to distribute mochas to twitchy Soho-ites, she still had a disconcerting way about her. An old-fashioned thing. Hips, heels and cigarettes, all that stuff. You seen Gilda? No? 1946? Rita Hayworth, Glen Ford? Or what about Only Angels Have Wings? Hayworth and Cary Grant, 1939? Well, she looked like that. Like she’d have fluffy mules under her bed and a gun in her purse. Plus for someone who’d been hauled out of her car and dumped in the gutter by two ASBOs not twelve hours ago, she was holding it together.

“You’ve never –” I repeated back in a stupid high-pitched voice, spilling a little latte. “It’s a classic. Redford? Shaw? Newman? Got that Joplin ragtime score?”

Laura peered over the yellowing poster, eyes finally settling on the bottom right of the frame.

“Six hundred pounds?” she yelped.

“I know I know. But I’ve had it signed by the artist Richard Amsel, here see? And Shaw and the director. There’s another dealer who comes in for a drool over it almost daily. It should just be for display really but the way things are, I’m sort of hoping he’ll –”

“And what’s in these?” Laura said. She slid a bun from a greasy paper bag and moved on to one of a dozen or so fat files on the counter among the post and the remains of the morning’s particularly heated Buckaroo.

“Posters. Well, photos of posters. The originals are in tubes downstairs.”

“Like a nerd Argos,” she said flapping past polaroids of Heat, Heathers and Heaven’s Gate.

“Although, that’s now ruined,” I said, plucking Hellraiser out grimly. “And that. And that.”

“Ruined?”

“Like me,” I sighed. “Down here.”

We moved behind the counter, through the arch and down ten rotten steps from the dull glare of the shop floor to the single-bulb gloom of the wet basement. There are in fact twelve rotten steps to the basement but as the concrete floor was still under nine inches of thick black water and Laura’s plimsolls seemed less than aquatic, I thought it best we remained poolside.

“Ohmigod,” Laura said, hand over her nose. “It stinks. This is what you meant yesterday by –”

“Quite.”

“Where does that go?” She pointed across the dripping dungeon gloom to an iron door, purple with rust in the furthest wall.

“Into next door’s basement. Antiquarian books. Fortunately for all his stock it’s rusted over and water tight.”

“Christ. And what’s in all those boxes?”

“Now? Vintage fist-fulls of mushy pulp. Likewise the bottom two shelves all along that wall and everything in those bin bags.”

“Urgh, God. And it all used to be –”

“Yep. Used to be.”

There didn’t seem much more to add. Laura said it stinks a couple more times and I agreed a couple more times and that was pretty much that. I snapped off the basement bulb and we ascended to ground level, the furry smell clinging to my sopping turn-ups. Laura started up a new cigarette to cover the black odour, I told her she couldn’t smoke in the shop and she held up her cigarette to demonstrate that she could, look, when Mr Cheng arrived for his daily drool.

“You be oh eBay?” Cheng said, door jingling, pulling his spectacles from his brown suit pocket and cleaning them on a pale brown hanky.

“Not yet,” I said.

“Ny Ac Com nuh fouh. Oh prih buh noh bah.”

Mr Cheng never bothered to finish words once he’d started them. It had taken me a few months of conversation to be able to mentally fill in the blanks quickly enough to keep up.

“You shouh looh. Cheh ouh,” he said, sliding on his specs.

“I will check it out. Thank you.”

Laura perched on the edge of the desk and took it upon herself to open the rest of my mail. I asked her kindly not to, at which point she offered me a withering feminine look – which as I explained, I never know what to do with so I busied myself with Cheng. I watched him crane his neck over my poster for The Sting, peering over the signatures behind the glass. He stepped back once in a while to take in the full image, and stepped back in just as quickly to watch the ink, as if he’d spotted it slithering across the faded paper.

“Fye hundreh,” he said, as he did every morning.

“Six hundred,” I said, as I did every morning.

“My guy, he big colleck.”

“Yes, so you keep saying.”

“I geh hih thih, he buy loh moh. Buh he say whon pay moh thah fye.”

I opened my mouth to administer the daily rebuttal but nothing came out. The words hovered apprehensively at the back of my tongue like stage-struck toddlers and for the first time, I allowed Cheng’s offer to ruminate seriously. Five hundred pounds. More than I made in a day. More than I made in a week. I looked down at my soggy turn-ups and shiny wellies. Thought about the stacks of bin bags beneath me. The rows and rows of sopping boxes. I thought about a Freshers’ Week fifteen long years ago, my hall-mate Andrew and I hanging the poster on the wall of my new room. Thought about what five hundred pounds would do.

“Let me think about it,” I sighed finally.

Cheng blinked, removed his glasses and scuttled out.

“See yoh tomorr.”

“I expect so,” I said, and he closed the door behind him with a ting-a-ling.

“Dear Mr Martin, in response to your letter of the fifteenth …” Laura said suddenly. I looked over. She had her cigarette perched between her lips and was unclipping a photograph from the letter in her hand. “Blah blah blah, without a viewing, we are unable to put an accurate valuation …”

“Sotheby’s,” I said, reaching out for it.

“Although,” she said, twisting around away from me, lifting the letter out of reach. “In line with Overstreet’s current price guide, we would estimate a value of –”

“Can I take a –”

“Holy shit, Mr Heroes Inc. I think your problems are over. You own this?” and she held out the Polaroid. I nodded sadly.

“Don’t get too excited. I can’t sell it. It comes as part of the package when you have an honourable wife.” I took the letter grimly and read it through, chewing the inside of my cheek.

“Honourable?”

“My wife. Jane. Despite her appearance and her love of Tank Girl and Terry Pratchett, her dad is Edward, the somethingth Earl of whassitshire,” I explained. “Walsingham. No, Wakingham? Wakefordsham? One of those.” I dumped the Sotheby’s letter in my in-tray and picking up the final piece of ominous post, tore it open roughly. “Means he’s got a draughty old house in Suffolk that’s falling to pieces. Or is it Norfolk? One of the ‘folks’ anyway. A five-bedroomed whassit off the King’s Road, complains about income tax, thinks I’m a scruffy pleb and drags Jane off in a frock to stand in a field staring at ponies every summer. He likes his extravagant wedding presents of course. They’re designed to keep unworthy sons-in-law in his debt. To keep one in one’s …”

My voice trailed off into a croak as I tugged out the flimsy yellow carbon paper from the final envelope, stomach rolling over and flopping out like a fat drunk on a guest bed.

Shit.

Laura was talking somewhere but her voice was thick and muted, like it was underwater. Like she was sunk. Sunk like me.

I blinked at the final demand and refocused. Rod-o-Matic, Plumbing & Drainage.

I recalled the man in overalls. The unpacking of gear. The pipes. The hours of juddering compressed air. The repacking of the gear. The apologies.

“What about insurance?” Laura asked, snapping me awake. She was stubbing out her cigarette and popping the top from a coffee. “Doesn’t that cover burst –”

She stopped at the sudden shutter-shuddering slam of the door.

“You Hero? Hey, you?” a wide gentleman barked, barraging in, banging a brown evacuee suitcase against the displays. Draped in a ratty old coat, clearly tailor-made for someone else, a greasy wool hat pulled right down, his voice was muzzled by a spitty scarf.

“You Mr Hero? I’ve got shit to shift. Right up your alley.” Waddling up the aisle, he heaved his battered case onto my photo files.

“Can I help you?” I said, clearing some space.

He flicked the case locks with grubby thumbs.

“It’s me who’s ’elping you mate. What’ll you give me for this lot?”

I put the invoice aside and wiped croissanty fingers on my jeans. Glad of the temporary distraction, I spent the next five minutes rootling through the cluttered contents of the old man’s musty suitcase. Despite everything – invoices and cellars and solicitors and intimidating café staff – I allowed my mood to momentarily lift, feeling the old hope tingle like warm electricity through my fingertips. I breathed it in: the fusty brown smell; the crackle of yellowing paper; the rustle of polythene and dull clink of thick porcelain. Boxes, bundles and bags, bulging with possibility.

Forgive me.

Long forgotten cases like these are the most enjoyable part of a dealer’s life. More than a ringing till, more than that first cappuccino. Not due to any rookie pipe-dream of a mythical priceless trinket mind you. Those ideas are pummelled out in the first six months by the fat fists of experience. In almost a decade of running Heroes Incorporated, not one of the hundreds of identical cobwebby suitcases has yet to give up more than a tenner’s worth of chipped pop-culture nick-nackery.

No. What these moments give is a return. A chance, for the briefest moment, to remember, recapture, the few precious seconds of boyhood when our strange fascinations first took hold. For a frozen moment business is forgotten and I am back in short trousers and school shoes, eyes wide, breathing in the smell of burnt popcorn. I am stroking the rough primary pages of a borrowed comic, bathing in the tinny glow of a Saturday cartoon or picking cold fingers among the trestle-table tat in a freezing church hall jumble sale, my father beside me, slipping me a heavy fifty pence, the air bubbling with women’s voices, thick with the metal smell of orangey tea.

I was jerked from memory by a loud voice. I looked up from the worthless case of trinkets and tat. The owner was taking a vocal stroll about the shop, letting fly with his expert advice. Ahhh, you wanna get rid of all this crap. This? This here? Worthless. These are on eBay for twenty pence. Market’s flooded with ’em. Crap, crap, crap, whassis one? Crap. On and on. Jolted by disbelief, I threw a look at Laura who dropped a matching jaw and threw the look back.

And then if this wasn’t enough, the stranger, seemingly oblivious to buyer-seller etiquette, up-shifted a gear with a crunch and started getting personal. Gor dear, fuckin’ amateur hour this place. Got stuff worth more than this kickin’ around in my loft. New to the game are you Hero? He’s calling me ‘Hero’ the whole time for some reason. Hero, eh mate, new to this lark are ya? Bloody youngsters don’t know what the fuck you’re doing. Do ya. Hoy? Hero?

Well I mean, really.

I was this close to slamming his ratty case and asking him to take his bric-a-brac, business and body-odour elsewhere when, at the bottom of the case, beneath a yellowing stack of 2000ADs, my fingers curled around a thick roll of what felt like card. I tugged it loose.

Black and white photographs. Publicity stills. Cracked and faded most of them, corners bent and orangey. A quick crackle through revealed a veritable who’s who of artists and writers from the thirties and forties – the Golden Age of the American comic book: Will Eisner, Bill Finger, Julio Raymond, each posed in shirt sleeves and fedoras, pipes in mouths, all sat chuckling around desks and easels. Shots commissioned no doubt by various publishers way back when. A quirky collection but nothing to get too excited over.

I was already warming up a thanks-but-no-thanks when two familiar faces at the bottom of the photo pile caught the words in my throat.

Could it … ?

Was it … ?

Holy.

Heirloom.

Batman.

I swallowed hard and looked up. The man had got his coat caught on a rack and was cursing and tugging at it, postcards and lobby sets swooping to the floor.

“Er, not really my sort of stuff to be honest,” I said, attempting to keep the wobble from my voice. “I mean I’d give you a fiver just coz I like this Dick Tracy mug,” and I waved a ceramic Warren Beatty. “But I’d be doing you a favour to be honest.”

“Fuck off ya tosser, got some beauties in there,” the man said, yanking his coat free, the postcards falling around. “Them 2000ADs are mint. Hundred quid and it’s all yours. C’mon ya tight fucker. You’ll make double that.”

“I’d be lucky to make half, to be honest. And would you mind controlling your language sir?”

“Then give me a fuckin’ decent fuckin’ price, ya fuckin’ fairy. Seventy five,” and he waved a grubby paw at the large MGM posters on the wall. “You’d only spend it on more Judy Garland shit for your boyfriend.”

“For my boyf – ? Oh for heaven’s sake.” In the corner Laura was concealing a smirk behind her cigarette. I really was going to have to butch the place up a bit. But until then, I needed to close this deal sharpish. “Fifteen, and it’s my final offer.”

“Twenty.”

“Fifteen.”

“You … Give it then,” he barked in a belch of boozy bitter, snapping his fingers. “An’ I want a receipt.”

I began jabbing through the laborious temperamental quirks of my Jurassic till, the man spitting ’urry ups and fackin’ell mates, in your own time why dontchas. The till-drawer finally ground open, thin receipt chattering out noisily. I peeled off a couple of notes and handed them to him.

“’Bout time, ya fuckin’ fruit,” he mumbled, upending the case to let the comics, photographs and nick-nacks tumble to the counter and floor in a flurry. He staggered around and clomped mumbling down the shop, lurching clumsily onto Laura’s toe. She yelled at him but with a thud and a clatter he was gone.

“Jesus. What an arsehole,” Laura said.

“And thank the Lord,” I said excitedly, riffling through the debris.

“Otherwise I might have felt moved to give him the full market value for … where are you, where are you … here. Look at that!”

Laura ambled up the aisle and peered at the photograph through her cigarette smoke.

“And what is the market value,” she shrugged, “for a signed snapshot of two Brylcreem boys with their underpants outside their trousers?”

“A great deal more than fifteen pounds,” I said, heart lifting. Maybe this was a sign? Maybe it was like my dad used to tell me – that luck came in streaks? Run of bad, a run of good.

I caught a glimpse of the yellow plumber’s invoice atop my in-tray. Further down the pile, two matching yellow demands and a Beevers & Boatman letterhead peeked out a little.

Christ, let my luck be changing.

“Fur-mur fob-mim oof,” Jane said later that evening, to which I replied “Beg pardon?” for the obvious reason. “You robbed him?” she said, lifting her mouth up from the pillow a bit, and then added another small oof noise.

“Robbed – I didn’t rob him,” I said. “It’s not like he – whoopsie – like he came in and I clunked him over the head with a cardboard Chewbacca and nicked his suitcase.”

The whoopsie was because the essential oils I was massaging into Jane’s shoulders had got a bit runny and began getting under my watch-strap. I warmed up a spot more liquid between my palms with a noisy rubbing motion and resumed the long broad strokes along Jane’s pale shoulders. “I offered him fifteen pounds and he took it,” I went on. “Fair and square.”

“Fair?” Jane said, twisting to look up at me. I shushed her back into position. “Well then I hope you never get old and have to sell any of your –”

“Oh c’mon, shush shush, this is meant to be relaxing.”

The lounge dropped into quiet once again, just Michael Nyman’s score to The Piano tinkling softly from the (£10 o.n.o.) stereo. Lana was asleep in her cot next door, a chunky baby monitor propped up by Jane’s pillow crackling murmurs and sighs. The flat smelled of our weekly date night. Baby poo smothered with oils, candles and clean towels. Propped up behind her, straddling the small of Jane’s back, I rubbed and smoothed her soft bathtime skin and tried to enjoy the moment.

Jane shifted a little, brushing bath-wet hair from her face.

“How is it fair?” she said. “Fair, surely, would have been telling him what a picture like that was worth and offering him two hundred pounds? Or a hundred at least? That would have been fair. Do you know where he got it? Maybe they’re his wife’s collection.”

“Wasn’t very ladylike stuff.”

“Right, we going to have that conversation again? When we met, I had more copies of 2000AD than –”

“All right, shush shush, you –”

“Your team all cocky at the Freshers’ Week quiz. Playing the girls …”

“You win, you win,” and I gave her a soft kiss between her shoulder blades, inhaling her bathtime scent.

“All I’m saying is, maybe they were her pride and joy? Down a bit.”

“Then why is he selling them door to door out of a suitcase? There?”

“Maybe she died? Right there.”

“Yes maybe,” I said. “But it looked more like he was about to spend the money on booze.”

“Naturally. Drowning his – ooh, that’s good, a bit more there,” Jane said. “Drowning his sorrows. Married thirty years. She has a heart attack, he’s left alone. Forced to sell her rare collections to meet the funeral expenses?”

“You wouldn’t be saying this if you’d met him.”

“Poor old chap.”

I thumbed the dip beneath her left shoulder silently for a moment.

Did I want to tell her that I didn’t have a hundred to give him? That apart from a listless Kerplunk and Cheng coming back in for another peer at Robert Redford at ten past four, I didn’t have another customer and spent the rest of the day knee-deep in antique papier-mâché? No, I thought. Best not.

I moved across to Jane’s right shoulder, gazing over the pale violin of her back. Swallowing hard I tried to concentrate. My wife. My perfect angel. But even there, hands kneading gently her velvet curves, guilt stared back. Plain guilt. The word stared up at me from her shoulders like Jane was a premier league football player and it was the tattooed name of her firstborn.

“But think about it hon. I do the nice thing, the honest thing,” I jabbered, giving the word as naïve and foolish an inflection as I could. “Give the bloke two hundred and fifty quid, which is what a signed promo shot of Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel is worth –

“Neil, you know that’s not –”

“And then sell it on for two hundred and fifty, what’s been the point of that? I’m trying to make a living here. For us. But if you’d rather I didn’t …” I said, somewhat petulantly.

It was a strategic manoeuvre. It was only a matter of days before Jane discovered what I’d done. How much I’d screwed up. And I knew that when she did – when the smoke cleared and she was able to pick through the debris of what used to be her life – I was going to be on the wrong end of a very big row. A plate-hurling, parent-phoning, locks-changing, never-want-to-see-you-again scale bust-up. So I was pushing this point as preparation. Ground work. Something I could barter with later. But hon, when I tried to make a little money to put things right you accused me of being unfair. Ow, ow that hurts, I’m sorry I’m sorry ow.

Something like that.

Jane was laying quietly. She does this during disagreements. The silent thing. Implying I’m not worth listening to. Which makes me frustrated and shouty and incoherent and not worth listening to.

“All I meant was,” she said, “you could have been nicer.”