8,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Amber Books Ltd

- Kategorie: Bildung

- Sprache: Englisch

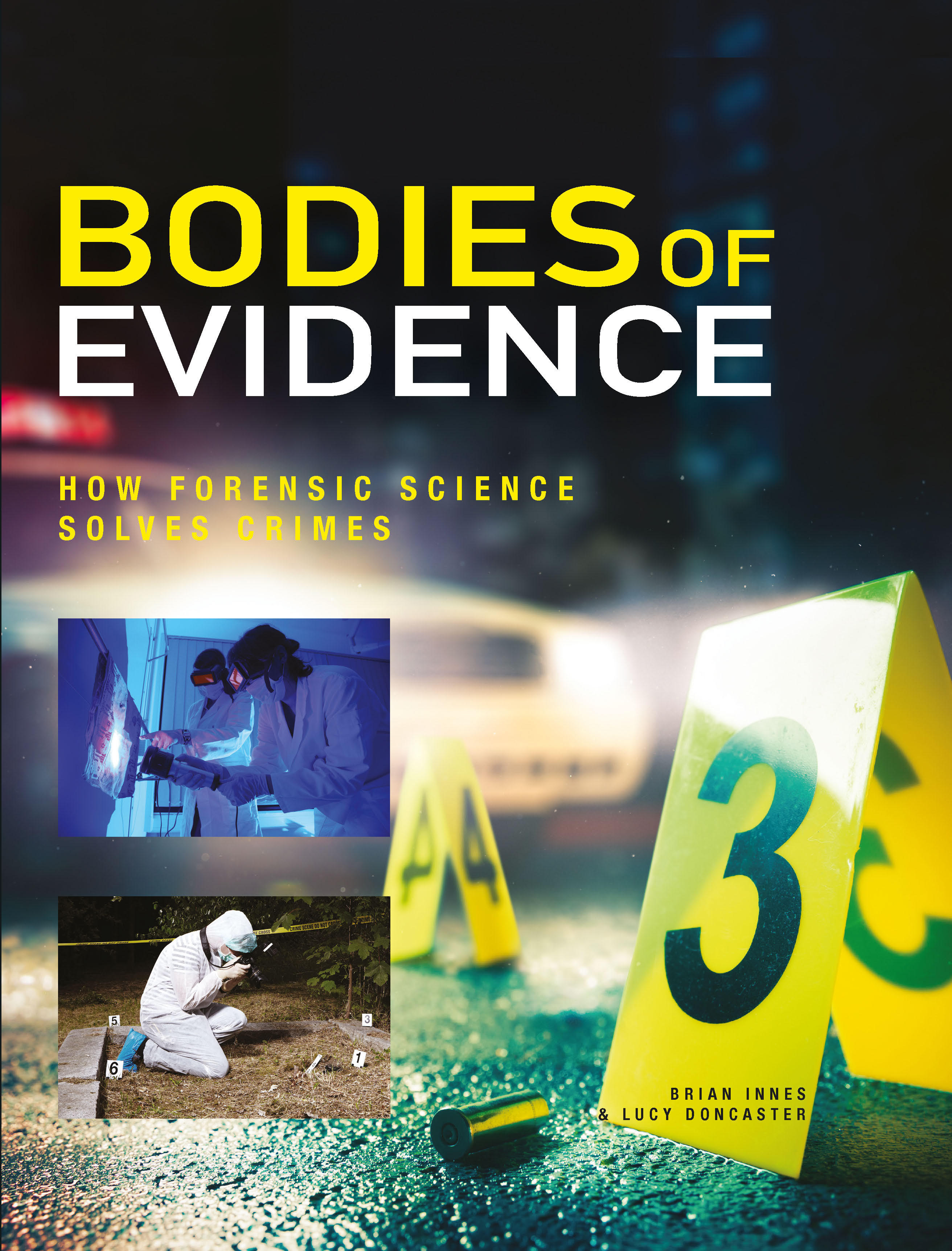

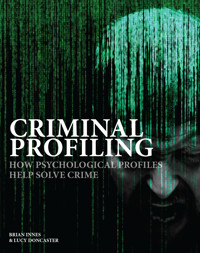

Is there such a thing as a criminal type? Are criminals born genetically predisposed to commit crimes, or are they fashioned by their circumstances? Physicians, psychologists and criminologists have been asking these questions for many centuries, without finding a definitive answer. Criminal Profiling is packed with intriguing case histories that demonstrate the variety, sophistication and effectiveness of criminal profiling. The book includes chapters on the search for the criminal personality, early criminal profiling and the latest theories of criminality, and features the stories of Ted Bundy, Peter Sutcliffe and Andrei Chikatilo, among many others. Illustrated with 200 colour and black-and-white photographs, Criminal Profiling is a wide-ranging, authoritative history of this fascinating subject, from the first efforts at physical profiling to today’s computer-generated geographic mapping techniques.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 407

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Ähnliche

CRIMINAL PROFILING

CRIMINAL PROFILING

HOW PSYCHOLOGICAL PROFILES HELP SOLVE CRIME

BRIAN INNES & LUCY DONCASTER

This updated digital edition published in 2024

First published in 2003

Copyright © 2022 Amber Books Ltd

Published by Amber Books Ltd

United House

North Road

London N7 9DP

United Kingdom

www.amberbooks.co.uk

Instagram: amberbooksltd

Facebook: amberbooks

Twitter: @amberbooks

Pinterest: amberbooksltd

All rights reserved. With the exception of quoting brief passages for the purpose of review no part of this publication may be reproduced without prior written permission from the publisher. The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. All recommendations are made without any guarantee on the part of the author or publisher, who also disclaim any liability incurred in connection with the use of this data or specific details.

eISBN: 978-1-83886-549-8

Project Editor: Michael Spilling

Designer: Jerry Williams

Picture Research: Terry Forshaw

CONTENTS

Introduction

The Search for the Criminal Personality

The Psychologists Investigate

Whoever Fights Monsters

A System of Identification

The Intuitive Approach to Crime Analysis

Behavioural Evidence Analysis

Geographic Profiling

The Criminal Word

Modern Theories of Criminality

Negotiation and Interrogation

BIBLIOGRAPHY

INDEX

INTRODUCTION

The criminal has been an unwelcome element of society since time immemorial, and the attempt to penetrate their mind, to discover whether they differ significantly from the person who is considered an honest citizen – and if so, to what degree – has preoccupied people for centuries. For a long time, most research was superficial, directed solely towards ways of identifying the physical characteristics of known criminals – an approach that was of limited value in the investigation or prevention of crime.

But as interest in the workings of the human mind developed, attention turned, either to ways of identifying the thought processes of criminals and therefore frustrating their future crimes, or towards the possibility of their subsequent reform. It is only within the last 120 years or so, however, that law enforcement authorities have come to realize that an analysis of the specific behaviour of an unidentified subject (UNSUB) can provide clues to their physical appearance, age, education, social position and other factors and so help the investigator narrow down the field of inquiry. And it is only with the present-day ready availability of desktop computers that it has proved possible to handle the vast quantities of data on which to base such an analysis.

This approach was originally named psychological profiling, but it is now generally given the more widely applicable name of “offender profiling” or “behavioural analysis.” In the beginning, it was principally the domain of psychiatrists and psychologists, whose assessments, based upon their clinical experience, were largely intuitive. In the United States in particular, however, the technique has been brought to its present state of development by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and in Canada by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Other nations have followed suit.

These two organizations have placed a reliance upon the analysis of computerized data that has now been extended to the use of geographical profiling. In Britain, the police computer systems HOLMES (and later, HOLMES 2) and CATCHEM were established as a result of the failure of conventional data gathering in the case of the “Yorkshire Ripper,” and other countries have now also followed the FBI example. In addition, there are many independent practitioners who offer their expertise – often to the investigating officers, but also to the prosecution, or even the defence, when an accused person is brought to trial.

There is controversy over who coined the terms “pyschological” or “offender” profiling, but the first systematized application of the technique undoubtedly came with the establishment of the FBI’s Behavioral Sciences Unit in 1972, and the subsequent development of ViCAP (Violent Criminal Apprehension Program) in 1984. Because of the FBI’s concentration on serial murder, rape,and abduction, most attention has been given to these crimes of physical violence; but, with authorities’ growing expertise and facilities, similar techniques are now applied to the investigation of a widening range of other crimes.

The use of behavioural analysis in the hunt for violent criminals – especially serial murderers and rapists – had developed with increasing success over the course of more than 20 years before it attracted widespread public interest with the release of the movie The Silence of the Lambs in 1992. Based upon a novel by Thomas Harris, the movie featured the cannibalistic psychopath Dr. Hannibal Lecter, who had already appeared in Harris’s earlier work, Red Dragon, published in 1981.

In writing Red Dragon, Harris had sought the advice of the FBI. He was invited to Quantico, the Bureau Academy in Virginia, and allowed to attend training talks on serial killers given by members of the Behavioral Sciences Unit. The character of “Buffalo Bill,” the killer who is tracked down in The Silence of the Lambs, is a combination of three real-life murderers who were used as examples in these talks.

When it came to the making of the movie of The Silence of the Lambs, the FBI was even more cooperative. They allowed the Academy at Quantico to be used for location shooting, and some scenes even included Bureau personnel in minor roles, or as extras. However, the FBI’s procedures in the movie provoked severe criticism, not only because the Bureau would never have used a trainee agent on such an assignment, but also because of various inaccuracies of procedures portrayed.

It is hardly surprising that the success of The Silence of the Lambs resulted in many subsequent highly popular fictional television series. Unfortunately, some of these have suggested that psychological profiling and behavioural analysis are almost “magic” in their potential, virtually infallible in hunting down the criminal perpetrator. Intuition and clinical experience can play an important part, but the key to success lies in the painstaking assembly of comparative data.

Modern shows are generally more realistic, and indeed there is a great appetite for true crime series such as Netflix’s Making a Murderer, HBO’s True Detective and the BBC’s Criminal: UK, some of which have revealed problematic police procedure and had a real-life impact on criminals’ judicial proceedings (see page 234).

Apart from this now widely practised technique of behavioural analysis, which is also of great value in interrogation and crisis negotiation, there are other approaches that can throw light on the personality and thought processes of the unidentified criminal – “getting a sense of what they’re all about.” In this book, attention is also devoted to what can be detected in verbal and written communications, by approaches such as psycholinguistics, textual analysis and the assessment of handwriting. It also takes a look at some modern technologies and techniques, from the role of AI and data processing systems to brain imaging, alternative interrogation techniques and more refined hormone treatments.

Over the past decades, many professional profilers have been happy to publicize their successes, revealing how their methods can spotlight unidentified offenders and bring them to justice. Alongside this, there is of course evidence of how the system has failed. Nevertheless, the study of the criminal personality, in all its ramifications, is of great importance. Getting inside the criminal mind is an increasingly powerful tool in the war against crime.

IN THE SEARCH FOR THE CRIMINAL PERSONALITY

For many centuries, physicians believed that an individual’s physical characteristics would reveal whether or not they had a criminal nature. This early 19th-century cartoon (left) satirizes the possibility that employees might be selected by phrenology – examining the shape of the cranium to gauge the personality.

How is it that some people become criminals, while the majority do not? When the same temptations face all of us, why do certain individuals succumb, while others keep to the narrow path of righteousness?

During many centuries, this question was dismissed, almost out of hand, for the answer seemed obvious: either criminals were born that way, unable to control their antisocial instincts, or they had become possessed by malign beings – evil gods, demons, or even the Devil himself.

Ancient Greek philosophers and physicians looked deeply into the question of emotions, their cause and where they might originate in the human body – but their theories remained largely undeveloped for more than 2,000 years, until the time of Sigmund Freud and his associates around the turn of the 20th century. As early as the 6th century B.C., the physician Alcmaeon carried out the first dissection of the human body and decided that the seat of reason lay in the brain; while the philosopher Empedocles suggested that love and hate were the fundamental sources of changes in human behaviour.

As long ago as 400 B.C., the famous Greek physician Hippocrates described a range of mental disorders of the type that are recognized today, and he spoke out strongly for the legal rights of the mentally disturbed. At that time, Athenian law recognized the rights of the mentally ill in civil concerns, but not if they were guilty of serious crimes. The influence of Hippocrates brought about changes in the law: if a person on trial could be shown to be suffering from what he called “paranoia” (a term that will recur, with a more specialized meaning, later in this book), the court appointed a “guardian” to represent the accused.

A romanticized 19th-century portrait of Hippocrates, eminent physician of ancient Greece.

The famous Roman physician Galen (c.130–201 A.D.) theorized that the human “soul” was situated in the brain, and was divided into two parts: the external, which comprised the five senses; and the internal, which governed imagination, judgement, perception, and movement. However, over the next 1,500 years, Galen’s theories were almost completely ignored. The medical profession chose to maintain more primitive explanations for the causes of mental disorder, such as witchcraft or demonic possession.

PHYSIOGNOMY

It was during the 16th century that the idea emerged that it was possible to determine the nature of a person by his external features, such as the forehead, mouth, eyes, teeth, nose or hair. The study was named “physiognomy” by the Frenchman Barthélemy Coclès, and in his book Physiognomonia (1533) he provided many woodcuts to illustrate his points.

Gradually, from the 17th century onwards, various enlightened Western philosophers began to exert an influence on medical thinking, and it was at this time that the term “psychology” was first used. Nevertheless, although the effect of the brain – not only on behaviour, but also on diseases – came increasingly to be recognized, external physical characteristics remained predominant in diagnosis methods. One major theory, which contrived to combine both approaches and caught the popular imagination, was “phrenology.”

Franz Joseph Gall (1758–1828) was a fashionable physician in Vienna at the end of the 18th century, and he came to the conclusion that the brain was made up of 33 “organs,” whose position and developed size could be discovered by feeling the external “bumps” of the cranium. There were three classes of organ: those controlling fundamental human characteristics; those governing “sentiments,” such as benevolence or mirthfulness; and those of a purely intellectual nature, such as the appreciation of size, or the recognition of cause and effect.

“At the sight of that skull, I seemed to see, all of a sudden…the problem of the nature of the criminal.”

Cesare Lombroso

Among the organs that Gall claimed to have identified – which included one that he famously decided indicated the human desire for “procreation” – were those of murder, theft, and cunning. He and his disciple J. K. Spurzheim (1776–1832) – who later named a further four organs – were forced to leave Austria because their ideas conflicted with current medical opinion, but their theories were welcomed in France, Britain, and the United States. In Edinburgh, Spurzheim publicly dissected a human brain, and indicated the position of the various organs; and in the United States “practical phrenologists” travelled from fair to fair, claiming to cure both mental and physical disease.

Phrenology remained a popular preoccupation throughout the 19th century, but contributed little or nothing to an understanding of the criminal mind – although modern neurological research has in fact revealed areas of the brain that control emotions and behaviour. The first important development in criminology came, strangely enough, with a revival of interest in physiognomy.

CRIMINAL MAN

The Italian Cesare Lombroso (1836–1909) made one of the first serious studies of criminality. After serving as an army surgeon in the Austro-Italian war of 1866, he was appointed professor of mental diseases at Pavia. There, he began to carry out a succession of dissections on the brains of patients who had died, in the hope of discovering some structural cause for insanity. In this he was unsuccessful, but in 1870 he learned of the German pathologist Rudolf Virchow, who claimed to have discovered unusual features in the skulls of criminals – features that reflected those of prehistoric mankind, or even of animals.

“Reading the bumps” of the human skull, which supposedly revealed the size of specific “organs” of the brain beneath, continued to be of popular interest thoughout the 19th century, and well into the 20th. Phrenological heads such as this can still be found in many antique dealers’ shops.

Lombroso at once began to study the physiognomy of criminals in Italian prisons, and performed an autopsy on the body of an executed brigand, paying particular attention to the skull, in which he found just one small, unusual, physical feature, which resembled that of a rodent:

“At the sight of that skull, I seemed to see, all of a sudden, lighted up as a vast plain under a flaming sky, the problem of the nature of the criminal – an atavistic being who reproduces in his person the ferocious instincts of primitive humanity and the inferior animals.”

Lombroso’s revelation was supported by further studies, and he began to divide his cases into “occasional criminals,” who were driven to crime by circumstances, and “born criminals” – those who regularly committed crimes because of some hereditary defect that was apparent in their physical appearance. These “atavistic” individuals were distinguished by their “primitive” features: long arms, acute eyesight (like that of birds of prey), heavy jaws, and “jug” ears.

Cesare Lombroso, the Italian professor of forensic medicine. His first book, L’Uomo Delinquente, was published in 1876 and introduced the theory that different types of criminals could be detected by their physical characteristics.

In 1876, the year in which he was appointed a professor of forensic medicine, Lombroso published his findings in the book L’Uomo Delinquente (Criminal Man), which quickly achieved international renown. In a later book, Criminal Anthropology (1895), “the results of a study of 6,034 living criminals,” he summarized his findings:

“In Assassins we have prominent jaws, widely separated cheekbones, thick dark hair, scanty beard, and a pallid face.

“Assailants have brachycephaly [a rounded skull] and long hands; narrow foreheads are rare among them.

“Rapists have short hands…and narrow foreheads. There is a predominance of light hair, with abnormalities of the genital organs and of the nose.

“In Highwaymen, as in Thieves, anomalies of skull measurement and thick hair; scanty beards are rare.

“Arsonists have long extremities, a small head, and less than normal weight.

“Swindlers are distinguished by their large jaws and prominent cheekbones; they are heavy in weight, with pale, immobile faces.

“Pickpockets have long hands; they are tall, with black hair and scanty beards.”

Lombroso’s first book came under bitter attack from those who accused him – justifiably – of over-simplification. At the same time, some support for his theory of hereditary criminal types came the following year, with the publication of The Jukes by American sociologist Richard Dugdale. The founder of the Jukes line, a highly disreputable criminal character, was born in New York early in the 18th century, and Dugdale claimed to have traced 700 of his descendants, all but a few of whom had become criminals or prostitutes at some point in their lives.

The German pathologist Rudolf Virchow in his laboratory at the Berlin Pathological Institute. It was his observation of unusual features in the skulls of criminals that inspired Lombroso to study the appearance of more than 6,000 living criminals over a period of more than 20 years.

In the opposing camp, a particularly strong critic of Lombroso was the Frenchman Alexandre Lacassagne (1843–1924), professor of forensic medicine at the Lyon Faculty, who maintained that the causes of crime were social and declared, “every society has the criminals it deserves.”

Lombroso subsequently modified his theories, and in Crime: Its Causes and Remedies (1899) he pointed out findings that partly supported Lacassagne’s suggestion: When food is readily available, crimes against property decrease, while crimes against the person, particularly rape, increase. Indeed, towards the end of his life, Lombroso recognized that the “criminal type” could no longer be distinguished simply by physical characteristics alone.

The phrenological studies of the Austrian physician Franz Joseph Gall attracted much popular attention in the early 19th century. Enthusiastic supporters of his theories gave lectures and demonstrations, in crowded rooms, to people of all ages and professions.

ANTHROPOMETRY

Lombroso’s original theories were a development of anthropometry, a branch of anthropology that arose following the publication of Charles Darwin’s The Origin of Species in 1859. Anthropometry’s devotees spent their time taking physical measurements of human beings, and particularly their skeletons, in the hope of supporting – or refuting – Darwin’s theories about the evolution of humankind. One of those who applied the principles of anthropometry to the practice of criminal investigation was Frenchman Alphonse Bertillon.

Anthropometry at first attracted the attention of other criminologists, but it soon fell into disuse, when fingerprinting was internationally accepted as the sure method of identifying criminals. However, fingerprint analysis, like the Bertillon set of physical measurements, serves only as a means of identifying a previously convicted person, as well as being the means of connecting a suspect with the scene of a crime. Because it does not provide a way of detecting the possibility that a person may be genetically disposed to commit crime, some experts have continued to search for a connection between visible physical characteristics and the criminal personality. (In this respect, it must be pointed out that practitioners of palmistry – a subject that is regarded as little better than fraudulent witchcraft and superstition by the police and criminologists – claim to be able to detect psychological tendencies in the pattern of lines in the human hand.)

ALPHONSE BERTILLON

At the time of the publication of Lombroso’s first book, the president of the Paris Anthropological Society was Dr. Louis Adolphe Bertillon, who devoted his studies to comparing and classifying the shape and size of the skulls of different racial types. His son Alphonse (1853–1914) at first showed little interest in his father’s work. When he was appointed a junior clerk in the records office of the Police Prefecture, however, he realized that anthropological methods could be used to link newly arrested people to previous crimes. One of his father’s associates, the Belgian statistician Lambert Quetelet, had stated that no two people shared exactly the same combination of physical measurements, and young Bertillon proposed a related system of identification to his superiors.

Between November 1882 and February 1883, Bertillon painstakingly assembled a file-card system of 1,600 records, cross-referencing them with measurements he made on arrested criminals. It was on 20 February 1883, that he had his first success. A man calling himself “Dupont” was brought to him and, after taking his physical measurements, Bertillon began to go through his files. At last, triumphantly, he picked out a single card: “You were arrested on December 15th last year!” he exclaimed. “At that time you called yourself Martin.” The news of this success made headlines in the Paris newspapers. By the end of the year, Bertillon had identified some 50 recidivists, and in 1884 he identified more than 300. Police and prison authorities throughout France swiftly adopted “Bertillonage.”

Bertillon then began to make use of photography, both of arrested suspects and of the scenes of crimes. He established the procedure of taking portraits both full face and in profile – still the standard practice today – and also introduced what he called the portrait parlé (the “speaking likeness”). This was a system of describing the shape of facial features such as the nose, eyes, mouth, and jaw, and remains the basis of Identikit and other more modern identification systems, including facial recognition software that is now part of everyday life.

Photography was a relatively new technique that was eagerly adopted by the young Alphonse Bertillon (above). It became a valuable adjunct to his Bertillonage system and his portrait parlé.

Bertillon was at one time credited with the adoption of fingerprinting techniques, but in fact, although he sometimes recorded criminals’ fingerprints, he remained convinced of the superiority of his measurement system, and on more than one occasion missed the identity of prints on file. As other countries took up fingerprinting in the early years of the 20th century, the French system of Bertillonage was eventually discarded.

Here, a police officer takes Bertillonage measurements of a suspect’s ear at New York Police Department headquarters in 1908.

PHYSIQUE AND CHARACTER

The German psychiatrist Ernst Kretschmer published Physique and Character in the early years of the 20th century. In his book he described his researches in this subject, but it was not until as late as 1949 that the American William Sheldon, in Varieties ofDelinquent Youth, made the first systematic linking of body types with delinquency. He claimed that all people were of one of three basic types:

Endomorphs: generally soft, rounded and plump, and characterized as friendly and sociable and loving comfort.

Mesomorphs: hard, muscular and athletic, with a strongly developed skeleton. The personality is strong and assertive, with a tendency to be aggressive and, occasionally, explosive.

Ectomorphs: thin, weak and generally somewhat frail, with a small skeleton and weak muscles. They tend to be hypersensitive, shy, cold and unsociable.

Sheldon examined 200 men in a rehabilitation unit in Boston, compared them with a study of 4,000 students, and came to the conclusion that delinquents tended to be mesomorphs. This theory was further examined in Unraveling Juvenile Delinquency (1950) by Eleanor and Sheldon Glueck, who at first found some support for it, but eventually concluded that delinquency was related to a wider combination of biological, environmental and pyschological factors.

ALIENATED MAN

Early in the 20th century criminologists began to turn their attention away from the physical characteristics of the “criminal type” and towards the mental processes – the psychology – that led people to crime. They were encouraged by the new ideas being put forward by the Vienna school of psychologists, led by Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung (see Chapter 2).

Bertillon’s interest in photography led him to develop his “ladder camera,” raised sufficiently high to enable him to photograph the whole body of a dead person as it lay where it had fallen. Subsequently, photographs of crime scenes have become ever more important in investigations, and they are studied with great care by modern psychological profilers.

The modus operandi (MO) of a criminal – the type of tool used in a break-in, the way in which a murder is carried out, and many other characteristic factors – can be a valuable indication that can lead to the identification of the perpetrator.

The English sociologist Dr. Charles Goring was one of the principal critics of Lombroso’s theories. Dr. Goring reported that he had found as many cases of Lombroso’s physical types among English university students as among convicts. Developing his argument in The English Convict (1913), Goring argued that many criminals were of inferior intelligence, and made the direct connection between this and crime.

This is as sweeping a generalization as Lombroso’s classification of “atavistic” types, and there are many cases in which it is obviously not true. However, Goring also identified what he called the “lone wolf” – or what the economist and philosopher Karl Marx had named the “alienated man.” This is someone who feels isolated from his society, misunderstood, and therefore believes himself justified in following his own rules of behaviour and conduct. This concept of alienation has become a vital part in the psychological assessment of criminality.

THE CRIMINAL’S METHOD

Since the mid-19th century, police investigators have realized that the handiwork of many persistent criminals can be recognized from what is generally known as their modus operandi (“method of working,” usually abbreviated MO). The way in which a building is entered; the way in which a safe is broken open; the tools used; the type of explosive employed – or, in the case of murder, the way in which the victim is captured, killed and perhaps mutilated – all these can provide clear indications that a succession of crimes have been committed by the same hand.

In cases of serial murder, the killer often leaves a characteristic “signature” – the way in which the body is disposed of, or some other unusual evidence – at the scene of the crime.

This signature should not be confused, however, with the MO. The MO is learned behaviour, becoming modified and perfected as the offender becomes more experienced and confident. The signature, on the other hand, is something that the criminal has to do to reach emotional fulfillment. It is not absolutely necessary for the successful accomplishment of the crime, but is part of the reason why he undertakes the crime in the first place.

CASE STUDY: JACK THE RIPPER

Even after more than a century, “Jack the Ripper” continues to fascinate professional profilers. The crimes committed by this Victorian murderer provoked a wave of panic in the East End of London in the second half of 1888. The case is of particular interest to criminal profilers because it resulted in the first documented attempt at a psychological profile of a serial killer.

Between August and November, five women – all known prostitutes – had their throats brutally slashed, after which the bodies of four were horribly mutilated. On the morning after the first killing, a newspaper report stated, “No murder was ever more ferociously and more brutally done.” In this killing, and another that followed within a week, the woman’s abdomen was ripped open, but the mutilations were soon to become even more terrible. Popular fear was heightened three weeks later, when the Central News Agency received a letter with the signature “Jack the Ripper,” written in red ink. The letter read: “You will soon hear of me with my funny little games. I saved some of the proper red stuff in a ginger beer bottle over the last job to write with but it went thick like glue and I can’t use it. Red ink is fit enough I hope, ha ha.”

IT’S IN THE BLOOD

As researchers continued their remarkable advances in the science of genetics during the 20th century, they made what at first seemed to be an exciting discovery. In human beings, all the genetic information is held on 23 pairs of chromosomes, which control such physical factors as the colour of hair and eyes, the structure of the body, and so on. One pair of chromosomes determines the sex of the individual: in the normal female, these are denominated XX, and in the normal male, XY.

In the male, the X chromosome comes from his mother, and the Y chromosome from his father. However, some males are found to have a combination of three chromosomes, either XXY or XYY. As the Y chromosome was linked with masculinity, it was suggested that an XYY male would be a “supermale,” likely to be more aggressive, and possibly criminal. A report published in 1965 stated that there was a higher proportion of XYY chromosome in men confined in mental institutions than among the general population, and claimed that they had “dangerous, violent, or criminal propensities.”

This coloured thermograph shows pairs of chromosomes.

However, later studies showed that although a high proportion of XYY men had committed crimes, these were mostly petty property offences, and they were no more likely to commit violent crimes than normal XY men.

Sensational popular newspapers, sold for a penny, featured imaginative engravings of the murders committed by Jack the Ripper in the Whitechapel area of East London. This drawing is the artist’s impression of the discovery of the body of the first victim, on 31 August 1888, by a patrolling policeman.

On the last day of September, just two days after this letter was received, the bodies of two more women were discovered. The next day, the Central News Agency received a postcard, in the same handwriting as the letter, and apparently bloodstained. It claimed: “you’ll hear about saucy Jackys work tomorrow double event this time….”

This photograph of a passage and stairway shows the location of Jack the Ripper’s fifth murder.

Most experts are now convinced that the letter and postcard were a hoax, perpetrated by a journalist in order to heighten interest in the case. It is less clear whether or not another letter, apparently in a different handwriting, was genuine. This was sent two weeks later to a member of a hastily created Vigilance Committee. Dated “From Hell,” and signed, “Catch me when you can,” it contained a horrific trophy – half a human kidney.

“One of the requisites necessary to enable an investigating officer to work with accuracy is a profound knowledge of men.”

The fifth killing – the last positively attributed to the Ripper – was the most gruesome of all. The murder took place in the woman’s rented room, and the Ripper had plenty of time to carry out his bloody work. The head was almost completely severed, parts of the body were cut off and much of the flesh was stripped away from the bones and placed on a table nearby in a gory welter of blood. By this time, the police were speculating whether the murderer might even be a member of the medical profession.

The police surgeon who assisted in the autopsy on the fifth victim was Dr. Thomas Bond. He was originally called in to give an opinion on the Ripper’s knowledge of surgery, but he went on to provide the police with a description of the killer. Affirming that all five murders were committed by the same person, he told police investigators: “The murderer must have been a man of physical strength, and great coolness and daring. There is no evidence that he had an accomplice. He must, in my opinion, be a man subject to periodic attacks of homicidal and erotic mania. The character of the mutilations indicate that the man may be in a condition sexually, that may be called Satyriasis. It is of course possible that the Homicidal impulse may have developed from a revengeful or brooding condition of mind, or that religious mania may have been the original disease, but I do not think that either hypothesis is likely.

“The murderer in external appearance is quite likely to be a quiet inoffensive looking man, probably middle-aged, and neatly and respectably dressed. I think he might be in the habit of wearing a cloak or overcoat, or he could hardly have escaped notice in the streets if the blood on his hands or clothes were visible.

“Assuming the murderer to be such a person as I have just described, he would be solitary and eccentric in his habits, also he is likely to be a man without regular occupation, but with some small income or pension. He is possibly living among respectable persons who have some knowledge of his character and habits and who may have grounds for suspicion that he is not quite right in his mind at times. Such persons would probably be unwilling to communicate suspicions to the Police for fear of trouble or notoriety, whereas if there were prospect of reward it might overcome their scruples.”

Considering the possibility that the Ripper might have – at least – occupational experience of cutting and gutting meat or fish, Dr. Bond argued: “In each case, the mutilation was inflicted by a person who had no scientific nor anatomical knowledge. In my opinion, he does not even possess the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer, or any person accustomed to cutting up dead animals.”

In spite of the guidance provided by Dr. Bond, the police never apprehended the Ripper. There were other similar murders, but none bore his distinctive handiwork. Over the years, dozens of possible suspects have been named by researchers, from a mad midwife to Prince Albert Victor, the grandson of Queen Victoria. Crime writer Patricia Cornwell, in her book Jack the Ripper: Portrait of a Killer (2002), stated her conviction that the famous painter Walter Sickert was the murderer. Even the FBI offered an assessment on the occasion of the “Ripper” centenary – one that was strikingly similar to Dr. Bond’s (see Chapter 3). Only one thing is certain: it is likely that the identity of Jack the Ripper will never be proven.

DR. HANS GROSS

The formal investigation of crime was first detailed by Dr. Hans Gross in his System der Kriminalistik (1893). This was originally published in English as Criminal Investigation in 1907 and it remained the bible of police investigators for more than half a century. Gross (1847–1915) was an Austrian magistrate who stressed that crime investigation is a science and a technology. He became professor of criminology at the University of Prague, and then professor of penal law at the University of Graz.

Gross wrote: “One of the requisites necessary to enable an investigating officer to work with accuracy is a profound knowledge of men.… To this end, everything in life can be utilized: every conversation, every concise statement, every word thrown out by chance, every action, every aspiration, every trait of character, every item of conduct, every look or gesture, observed in others….”

Furthermore, Gross suggested that the experienced investigator might well be able to infer the personality characteristics of a perpetrator from the manner and nature of the crime, that is, from his modus operandi or MO. By the end of the 19th century, the foundations of the psychological assessment of criminals had been laid.

By the end of September 1888, four prostitutes had died at the hands of the vicious killer Jack the Ripper. These four murders were committed in the open, as in this illustration, but the fifth – and the last to be attributed to “Jack” – took place in the woman’s lodging.

CONAN DOYLE, SHERLOCK HOLMES, AND DR. JOSEPH BELL

For well over a century Sherlock Holmes has remained the most famous detective in fiction. The creation of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, he appeared in four novels and 56 short stories published over a period of 40 years, from 1887 to 1927. Much of Holmes’s brilliant detective work was attributed to his technical expertise. Doyle, through the conversations that took place between Holmes and Dr. Watson, delighted in explaining exactly how the great detective employed his analytical powers to deduce a person’s nature and profession, or a criminal’s personality.

Dr. Joseph Bell, Conan Doyle’s mentor at the Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, whose “eerie trick of spotting details” was taken as the model for Sherlock Holmes’s skill.

In developing a character for his first story, Doyle wrote:

“I thought of my old teacher Joe Bell, of his eagle face, of his curious ways, of his eerie trick of spotting details. If he were a detective, he would surely reduce this fascinating but unorganized business to something nearer to an exact science.” “Joe Bell” was Dr. Joseph Bell, consulting surgeon at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, and one of Doyle’s instructors while he was a medical student there.

“For some reason which I have never understood he singled me out from the drove of students who frequented his wards and made me his out-patient clerk, which meant that I had to array his out-patients, make simple notes of their cases, and then show them in, one by one, to the large room in which Bell sat.… Then I had ample chance of studying his methods and of noticing that he often learned more of the patient by a few quick glances than I had done by my questions. Occasionally the results were very dramatic.… In one of his best cases he said to a civilian patient: ‘Well, my man, you’ve served in the army.’

‘Aye, sir.’

‘Not long discharged?’

‘No, sir.’

‘A Highland regiment?’

‘Aye, sir.’

‘A non.com officer?’

‘Aye, sir.’

‘Stationed at Barbados?’

‘Aye, sir.’

‘You see, gentlemen,’ he would explain, ‘the man was a respectful man but did not remove his hat. They do not in the army, but he would have learned civilian ways had he been long discharged. He has an air of authority and he is obviously Scottish. As to Barbados, his complaint is elephantiasis, which is West Indian and not British.’ To his audience of Watsons it all seemed very miraculous until it was explained.”

Sherlock Holmes was introduced to the reading public in A Study in Scarlet, in which he first demonstrated his formidable investigative powers.

A few years after the first appearance of Sherlock Holmes in print, Dr. Bell himself confirmed his methods in a letter to a representative of the Strand magazine, in which many of Doyle’s stories were published.

He wrote: “Physiognomy helps you to detect nationality, accent to district, and, to an educated ear, almost to county. Nearly every handicraft writes its sign manual on the hands. The scars of the miner differ from those of the quarryman. The carpenter’s callosities are not those of the mason. The shoemaker and the tailor are quite different. The soldier and the sailor differ in gait, though last month I had to tell a man who said he was a soldier that he had been a sailor in his boyhood. The subject is endless: the tattoo marks on hand or arm will tell their own tale as to voyages; the ornaments on the watch chain of the successful settler will tell you where he made his money….”

It was from his early observation of Dr. Bell at work that Doyle originally derived Sherlock Holmes’s deductive methods, but – with a mixture of ingenuity and imaginative analysis – he developed the technique to a point where it could serve as an example to a real-life investigator.

The great French criminologist Dr. Edmond Locard, one of the founders of modern forensic science, was a fan of Sherlock Holmes, and recommended a study of Doyle’s stories.

THE PSYCHOLOGISTS INVESTIGATE

The famous Swiss psychologist Carl Gustav Jung (left) came to the conclusion that there was a “collective unconscious” that reflected the atavistic instincts of primitive humankind and divided personality into more than a dozen “archetypes.”

In spite of many sociological studies of criminality that were made during the first quarter of the 20th century, the first reported face-to-face psychological interview with a convicted killer was not made until 1930. This was conducted by the German psychiatrist Professor Karl Berg, who questioned the infamous serial murderer Peter Kürten, the “Vampire of Düsseldorf,” in prison before his execution in 1931.

Kürten, born in 1883, was described by his wife (whom he married in 1923) and by his neighbours as a mild, conservative, soft-spoken man, a churchgoer and a lover of children. At his trial, he wore a neat suit and, it is said, smelled of eau de Cologne. Yet Kürten was charged with nine counts of murder and seven other assaults with intent to kill, and he had confessed during his police interrogation to an orgy of rape, mutilation and murder.

His criminal career began at age 17, when he was sentenced to two years in jail for petty theft. Many other sentences followed – in fact, Kürten spent 20 of his 47 years in prison. It was in 1913, when he was released from jail following seven years of hard labour, that he committed his first murder. He found a 13-year-old girl lying asleep near the window of her father’s inn at Köln-Mulheim, and he strangled her before cutting her throat with a pocketknife. The child’s uncle was charged with the crime, but the evidence was considered insufficient to convict him – and Kürten went unsuspected.

Very little is known of Kürten’s activities in the years that followed; he is credited with a series of sexual assaults upon women, although few were reported to the authorities, and Kürten was not identified. Then, in 1929, a wave of near-hysteria swept through Düsseldorf as a succession of 23 attacks occurred, mostly on young women and girls. In February of that year, a young woman was stabbed 24 times with a pair of scissors, but her screams scared off her assailant, and she survived. Six days later, a nine-year-old girl was stabbed to death, also with a pair of scissors, and an attempt made to incinerate her body with kerosene. After another four days, a male drunk was killed in the same manner, and his killer drank the blood that spurted from his wounds.

In 1929, a wave of horrific murders caused alarm throughout Düsseldorf. Here, a group of citizens reads a police notice about the latest killing.

In August, a young woman suffered a similar fate. This was followed by two unsuccessful attempts at murder, where the intended victims were fortunately able to escape and give a partial description of their assailant to the police. However, more killings followed, including two five-year-old girls. The killer had now abandoned his scissors, and instead used a hammer to batter his victims to death.

VAMPIRE’S MISTAKE

In May 1930, the “Vampire of Düsseldorf,” as he had been dubbed, made a fatal mistake. He picked up a young woman from Cologne, 20-year-old Maria Budlies, who had just arrived in the city looking for work. He took her to the apartment he shared with his wife, where he attempted to rape her, and then to a nearby wood, where he began to strangle her. Suddenly, he released his grip and asked her if she remembered his address. When she had assured him that she did not, he unaccountably let her go.

Photographs of Peter Kürten, taken by the police after his arrest, reveal him as an unexpectedly calm and self-confident individual – the very model of a responsible citizen.

Maria did not report the incident to the police, but described it in a letter to a friend. By a happy coincidence, the letter had been incorrectly addressed, and was opened by a clerk at the post office. He immediately handed it to the police, who tracked down Maria – and she, in fact, remembered significant details of the man’s address. Taken there by detectives, she was shocked to see her attacker leaving the premises – a man, the landlady said, named Peter Kürten. The next day, Kürten’s wife went to the police and told them that her husband was the feared Vampire of Düsseldorf.

At his trial, Kürten pleaded insanity, but the plea was dismissed; he was found guilty on all counts, and sentenced to be beheaded. In prison, he talked frankly with Professor Karl Berg. He said he was one of 13 children born to a sand-moulder and his wife in Köln-Mulheim. Kürten’s father was a drunkard who beat and abused both his wife and his children, and later was sentenced to jail for attempted incest. Even as a young child, Kürten showed a violent disposition, attempting to drown one of his playmates by holding his head under water.

Professor Berg reported that Kürten was a very early sexual developer. He said that he had begun to derive sexual pleasure from assisting the local dogcatcher in torturing and killing animals. At the age of 13, Kürten started practising bestiality. Later, he became an arsonist: “The sight of the flames delighted me,” he said, “but above all it was the excitement of the attempts to extinguish the fire, and the agitation of those who saw their property being destroyed.”

The psychiatrist was struck by the killer’s frankness and intelligence and his ability to recall his activities over the past 20 years. At the age of 16, said Kürten, he had visited the Chamber of Horrors in a local waxworks museum. “I am going to be someone famous like those men, one of these days,” he told a friend. Later, the story of Jack the Ripper excited him. “When I came to think over what I had read, when I was in prison,” he said, “I thought what pleasure it would give me to do things of that kind when I got out again.” He told Berg that he had stared with longing at the bare throat of the stenographer who recorded his confession, and was filled with the desire to strangle her.

At his trial, Kürten stated: “I did not kill either people I hated or people I loved. I killed whoever crossed my path at the moment my urge for murder took hold of me.”

He ate a hearty meal before he was beheaded, and it is said that he turned to his executioner on the scaffold and asked: “Will I still be able to hear for a moment the sound of my blood gushing? That would be the pleasure to end all pleasures.” Professor Berg described him as a “narcissistic psychopath,” and “a king of sexual perverts.”

At his trial, Peter Kürten appeared in a neatly buttoned suit, with a meticulously knotted necktie. It was reported that he had even sprayed himself with eau de Cologne.

FREUD, JUNG, AND ADLER

Karl Berg wrote a landmark book on the case of Peter Kürten, but it was not published in English (as The Sadist) until 1945. Meanwhile, psychologists devoted their attention to adapting mainstream theories to the study of criminality.

During the 1930s and 1940s, the principal theories in psychology were those of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), his former collaborator and colleague Carl Gustav Jung (1875–1961) and Alfred Adler (1870–1937). Freud was the pioneer among this group – all three of whom were psychiatric practitioners in Vienna – and he began to develop his theories by referring to his own experiences and emotions. As he recalled incidents from his childhood and compared them with those of his patients, he came to the conclusion that sexual instincts were present in infants from the very beginning, and could develop in different ways depending upon influences within the family. This resulted in his concept of the “Oedipus complex,” his description of the erotic feelings of a son for his mother and concomitant sense of competition with his father.

Freud began to analyze his dreams and those related to him by his patients. In his major work, Die Traumdeutung (The Interpretation of Dreams, 1900), he stated that dreams are disguised wish fulfillment – the evidence of repressed sexual desires. Despite the hostility of the medical establishment he persisted in this view, finding manifestations of sexual instincts in every instance of social, and antisocial, behaviour. In later publications he developed theories of the division of the unconscious mind into three parts: the “id,” which is associated with instinctive impulses and the desire for immediate satisfaction of primitive needs; the “ego,” which is aware of itself, is most in touch with external reality, and exerts control over behaviour; and the “super-ego,” which is a largely unconscious element that incorporates the absorbed moral standards of the family and wider community, and includes the person’s conscience.

A diagram sketched by Freud to indicate the way in which he believed repression worked.

Freud and his family escaped from the clutches of the Gestapo when the Nazis overran Austria in 1938, and settled in England, where his daughter Anna (1895–1982) became an eminent child psychoanalyst.

Jung, a younger man, originally from Switzerland, was for some years a disciple of Freud, but in 1913 he broke away from Freudian theories and developed ideas that, ironically, reflected an approach to psychology that was reminiscent of Lombroso’s discredited anthropometry. Analyzing his own dreams, Jung came to the conclusion that there was a “collective unconscious” that reflected the “atavistic” instincts of primitive humankind. He divided personality into over a dozen “archetypes.” He believed that more than one of these types is likely to be revealed in any individual. Jung is also responsible for the distinction between “extroverts,” who possess an aptitude for dealing with the external world and other people, and “introverts,” who concentrate their feelings inwards upon themselves.

Sigmund Freud’s pioneering work on the interpretation of dreams, and the emphasis he placed on their significance as indicators of repressed sexual desires, laid the foundations of modern psychological theory.