Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: THP Ireland

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

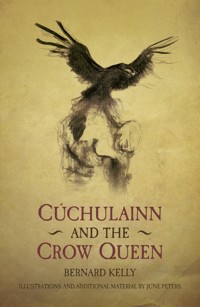

These stories have been told for 2,000 years. At their heart stands the great Ulster hero, Cúchulainn and on his shoulder sits a dark goddess in the form of a crow. She is the mistress of chaos, surveying the slaughter as he whirls in fury through an ancient yet still familiar world. Their dynamic force has helped shape the history of Ireland – its tribes, its warrior queens, its dispossessed kings. Harnessing the imagination of a modern storyteller, using often overlooked material, this work is an exhilarating retelling of an epic journey – following our champion from a disputed birth through to the battle of the bulls and beyond.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 184

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

In memory ofGary Henry and Rob Peters

CONTENTS

Title

Dedication

Ancient Legends Retold: An Introduction to the Series

Introduction

1 Disputes

2 Three Hounds

3 The Wonder Smith

4 Pig Feast

5 A Call to Arms

6 The Storyteller’s Daughter

7 Gardens of the Sun

8 Shadow Lands

9 The Bird Catcher

10 Severed Tongues

11 Death of a Storyteller

12 The Homecoming

13 Crow and Crown

14 Husbands and Wives

15 War Cries

16 The Wooden Sword

17 Four Deaths and No Wedding

18 Massacre

19 Brothers in Arms

20 Wounds

21 The Bulls

22 Dog Meat

Copyright

ANCIENT LEGENDS RETOLD: AN INTRODUCTIONTOTHE SERIES

This book represents a new and exciting collaboration between publishers and storytellers. It is part of a series in which each book contains an ancient legend, reworked for the page by a storyteller who has lived with and told the story for a long time.

Storytelling is the art of sharing spoken versions of traditional tales. Today’s storytellers are the carriers of a rich oral culture, which is flourishing across Britain and Ireland in storytelling clubs, theatres, cafés, bars and meeting places, both indoors and out. These storytellers, members of the storytelling revival, draw on books of traditional tales for much of their repertoire.

The partnership between The History Press and professional storytellers is introducing a new and important dimension to the storytelling revival. Some of the best contemporary storytellers are creating definitive versions of the tales they love for this series. In this way, stories first found on the page, but shaped ‘on the wind’ of a storyteller’s breath, are once more appearing in written form, imbued with new life and energy.

My thanks go first to Nicola Guy, a commissioning editor at The History Press, who has championed the series, and secondly to my friends and fellow storytellers, who have dared to be part of something new.

Fiona Collins, Series Originator, 2014

INTRODUCTION

When Patrick came to Ireland, the High King refused to accept his new religion until the saint had raised Cúchulainn from the dead.

Exhumed, the great Ulster hero recounted his victories:

‘I played on breaths

Above the horses steam

Before me on every side

Great battles were broken.’

Cúchulainn then urged the king to turn away from his old gods and embrace this new sky god and escape the fate he himself now endured, an eternity in hell.

In this story, grafted onto the end of the Ulster Cycle, Cúchulainn acts as the bridge between the old ways and the new. It captures a mythic moment in time when a fluid oral pagan tradition was being transformed into a Christianised one, forever fixed to the page. With this tangible object came unfamiliar ideas of ownership and novel notions of possession. From this point on, these stories no longer needed to live in our beings or in the naming of the land to survive, but could be carried around outside ourselves.

The second patron saint of Ireland, Columcille, once visited Finnian, the Abbot of Moille. Taking a book from his host’s library, he secretly copied it out. When the king proclaimed, ‘To every cow her calf. To every book its copy’, laying down the first laws of copyright, Columcille refused to be bound by the judgment and give his copy back. In 561, he and his clan faced the king’s forces and although he won this battle of the book, when he saw the bodies of the slaughtered, he realised what he had done and sailed away from Ireland.

This left only one Irish patron saint still in situ – Brigid, who, as well as giving her name to Britain, was a recycled version of the Celtic goddess of storytelling. The Morrigu, the great Crow Queen, a battle goddess akin to Freya in the Norse tradition, who dealt in sex, death and cows, was not to be so easily incorporated into the new pantheon of saints. Although she struck a very different sense of awe to the one being propagated by the monks of the time, they still managed to preserve her in some of her glory in the texts they transcribed.

It was the power of words that brought Columcille back to Ireland in 590 on a mission to stop the poets and storytellers being expelled from the land. The king had become tired of the savagery of their satires, which sometimes caused even fierce warriors to drop dead from shame. Columcille argued that it was their praise songs and their stories that would keep the king’s memory alive long after he was dead:

‘If poets verses be but fables

So be food and garments fables

So is the entire world a fable

So is man of dust a fable.’

The storytellers stayed, but under stricter control. The warrior women of Ireland were not so fortunate. They were banned and the possibility of having a warrior queen like Medb, a visible representation of feminine sovereignty, was extinguished.

Cúchulainn was resurrected once again at the end of the nineteenth century, when writers such as Standish O’Grady refashioned dusty academic texts into a popular myth of national identity equivalent to the corpus of Arthurian legend. When this Celtic revival was in full flow, Cúchulainn’s hyper-masculinity was appealing to a literary elite, who, while extolling the earthy virtues of the peasant poor, rarely got their hands dirty themselves. He was seen as an embodiment of self-determination, a great defender of an embattled people. Some tried to turn the Celtic Titan into a clean-cut Achilles, while others revelled in him being an out-of-control killing machine whose rage destroyed everything in his way.

‘We may one day have to devote ourselves to our own destruction so that Ireland can be free,’ wrote Pádraig Pearse, believing that ‘bloodshed is a cleansing and sanctifying thing and a nation which regards it as the final horror has lost its manhood’.

Pearse was born in 1879, when O’Grady’s version of Cúchulainn was first published in his History of Ireland. As he grew, Pearse became imbued with the passion of this hero’s life, seeing it as symbolising ‘the redemption of man by a sinless god … like a retelling (or is it a foretelling?) of the story of Calvary’. Aged 19, he had already published a series of lectures on Cúchulainn, and ten years later he opened St Enda’s, a bilingual school aimed at countering the oppressive forces of the English education system, which he dubbed ‘the murder machine’.

The front hall of St Enda’s was dominated by a fresco of Cúchulainn taking arms and the words ‘I care not though I live but one day and one night, if only my name and deeds live after me’. The students used a Cúchulainn primer for the Irish language and each assembly brought a story from the Ulster Cycle.

They joked that Cúchulainn was virtually a member of staff, but the school curriculum was no laughing matter. A boy at St Enda’s was as likely to be given a rifle as a Bible on prize-giving day and evenings were spent making hand grenades under the supervision of the science master.

On Easter Monday 1916, Pearse and his comrades, including thirty of the boys, stormed the General Post Office building in Dublin. On its steps, Pearse read a proclamation declaring Ireland free. His command of poetical rhetoric mesmerized many of those who heard him. Newsboys distributed a printed version throughout the city.

When Pearse stepped out of the burning building, he emerged into the inferno of his own myth. He became a symbol of national desire, both Celtic hero and Catholic martyr when he was executed four days later.

In 1935, the most famous image of Cúchulainn, a pagan pieta, was unveiled in the GPO building in Dublin; a final fusing of Pearse’s memory into the story of the Ulster champion he adored. This representation, like most depictions of Cúchulainn’s death, features his nemesis, the Crow Queen, perched on his shoulder. She is the mistress of chaos; he is her creature and it is his refusal of her advances that brings him down in the end.

By the end of the twentieth century, Cúchulainn was resurrected yet again, cloaked in a Union flag and claimed in public murals as an ‘ancient defender of Ulster from Irish attacks over two thousand years’. This appropriation of the myth never really took hold. He was being set up to defend borders and fight foes that for him never existed. It is said that stories are like hungry ghosts. If left untold, they demand to be lived. Cúchulainn, it seems, will continue to be brought back to life as long as the red-mouthed Goddess holds sway in our world.

1

DISPUTES

Three sisters, three one-eyed midwives, met at the crossroads. Above them there turned the constellations of the sky. At their feet skulked a hungry whelp of a hound.

‘How did it all begin?’ asked the youngest sister.

‘With the battle,’ said the oldest one. ‘When the gods came from the north, they set their ships alight so there could be no turning back. Their dark goddess, the Morrigu, the great Crow Queen, descended and pierced the earth with her sharp claws. She stood astride the river of tomorrow’s battle and what was to come began to bubble up from out of its depths; heads, fingers, eyes and teeth. Picking through the bits and pieces, she began to stitch all together again; limb back to limb, hand back to arm, scalp back to head. With sinew and song, seamlessly she did her work, washing away the blood from the dead-eyed boys not yet born, cleaning their corpses, bathing their bodies, breaking their bones.

‘Then came himself, the Dagda, Old Fat Belly, a god with appetites equal to hers. Dragging that mighty thing that hung between his legs, ploughing it into the earth, he separated the land from the sea and the sea from the sky. With a stomach the circumference of a world, copulation would be tricky, but she, the seasoned war goddess, was used to difficult manoeuvres. He caressed the nine untied tresses of her hair and with each move towards her, the bodies floating on the current between them shuddered and gasped; lungs spluttered out fluid and filled with air.

‘Shaking and shivering, hollow-eyed men emerged out of the dark waters and were dried by the beat of her wings as she took to the air. Their fists grabbed spears as above them she soared. Yelling, they ran towards her other children on the other side. Eye to eye, hand to hand, they hacked at each other, spears humming overhead; the clashing of shields, the clatter of swords, the slicing through flesh, the piercing of points passing through skin, the strokes and the blows of the weapons. Side by side, pride fought with shame that day and both stumbled on ground slippery with blood.

‘Through the killing, the craftsmen made good, sharpening blades blunted by bone; refixing spearheads embedded in flesh. The carpenters stripped the felled trees, worked the wood and turned the forests into smooth shafts of light. The masters of metal mended what was broken, their bellows blowing sparks that flew as stars into the sky. The braziers melded and riveted all together again.

‘Above, the Crow Queen surveyed the slaughter, saw the fires die down and watched as two great beings met on the plain.

‘One had a great eye, a black hole, the eyelid pierced by rings of gold, pulled open by chains of iron. A look and you shrivel and die.

‘The other was a dancing deity, tracing the patterns of the sun across the face of the earth. He held a sharpened ray of light.

‘“Who stands before me now?” asked Balor, the one-eyed god.

‘“The one you tried to keep in the dark,” answered Lugh, the shining lad.

‘“I live in the dark,” said Balor, “Are you kin of mine?”

‘“I am the son of the daughter you kept locked in a tower without windows or words so that I would not be born into this world.”

‘“Yet you stand before me now,” said the unseeing one.

‘“You shut out the light, but the sun kept on rising.”

‘“Then, blood of mine, let me look at you.”

‘His warriors pulled on the chains and the eye began to open. Balor only saw the point of light just before it hit and burned.

‘Lugh stepped forward, turned his spear in the socket and took out the still staring eye. He held it high, a ball of light now ablaze in the sky.

‘Rising out of the guts of the dead, she, the Crow Queen, laughed.

‘“Even a god cannot outwit his own fate.”

‘Ascending into the air, she crowed over the battle won and sang the end of the world.

‘I see a cursed land:

summers without bloom,

orchards without fruit,

cattle without milk,

oceans without life.

‘There will be kings without courage,

old men without wisdom,

judges without justice,

women without sovereignty.

‘Every son will enter his mother’s bed,

every father will enter his daughter’s bed,

each brother will become his own brother’s brother-in-law,

each sister will become her own sister’s mother.

‘The whole earth

consumed by fire,

as my shadow

devours the sun.’

‘Sister, you end everything too soon,’ said the youngest one-eyed one.

Snow began to fall and the three midwives built a fire. The hound rested his head on each lap in turn, as three eyes stared into the flames.

‘How did it all begin?’ asked the middle sister.

‘With the bulls,’ said the youngest one. ‘Of all the gifts the new gods brought; the shining spear of the sun; the everlasting cauldron of plenty; the screaming stone of destiny; surely the greatest one was the pig.

‘The gods had two pig keepers called Bristle and Grunt and although their masters, the god of the North and the god of the South, were fierce rivals, their swineherds were firm friends. “You know where you are with a pig,” said Bristle.

‘“Yes,” said Grunt, gazing into the eyes of his favourite sow. “They are the most faithful of creatures.”

‘“Not like a sheep,” said Bristle.

‘“Certainly not like a sheep,” said Grunt. “You would not confide in a sheep.”

‘“You would not,” said Bristle. “Foolish animals, sheep.”

‘“Thick as pig shit,” said Grunt.

‘“And what is this obsession with bulls?” asked Bristle. “Sure they have the balls, but do they have the brains of a pig?”

‘“No they do not”, said Grunt. “They are too belligerent.”

‘“Yes. Pigs,” sighed Bristle. “You could tell anything to a pig and know that the confidence would be kept.”

‘“Indeed it would,” said Grunt, “for a pig shapes a man into being a better human being.”

‘“Aye,” said Bristle. “A pig is a friend you can eat.”

‘“And there’s no finer thing in the world than that,” said Grunt.

‘The two pig keepers were well matched. If acorns rained down in the south, Grunt would invite Bristle and his pigs to the feast. If they rained down in Bristle’s territory then Grunt and his pigs would head north. So it was year after year, the pigs getting fatter and fatter and then fed to the gods to give them that everlasting life they so enjoyed.

‘But the gods have a habit of intruding even into the peaceful world of pigs. The gods of the North and South each wanted their herd to be the biggest and the best. They put pressure on their pig keepers to outdo each other or else they might find themselves out of a job. At first, nothing changed, but soon they began to talk and meet a bit less. Then one day when the acorns rained down in the south, Bristle was not invited to come. Grunt was never asked to come north again after that. And he cast a spell over Bristle’s pigs so no matter how much they ate they would not grow fat. Then Bristle cast the same spell over Grunt’s pigs and both were sacked for having skinny swine.

‘Deprived of their beloved companions, the ex-pig keepers became bitter and started to bicker and quarrel.

‘“I always had the biggest pigs,” said Bristle.

‘“Mine always had the tastiest flesh,” said Grunt.

‘And so it went on until, one day, their own bile became so unbearable that they turned into two birds of prey. Taking to the air as Talon and Claw, they cried of the beauty of pigs and the foolishness of kings.

‘Then diving down into the waters, they turned into two fishes – Ebb and Flow, spending days devouring each other in the depths.

‘Out onto the land they became two stags – Push and Shove, rutting in the spring.

‘Then two warriors – Point and Edge, endlessly slaying each other across the plain.

‘Then two banshees – Boundary and Space, wailing at the windows of the dying.

‘Then they fell to earth as two maggots, wriggling on the ground where they were eaten up by two cows, out of which they burst as two young bulls who within one day grew into the most magnificent creatures the land had ever seen: the great brown bull of Ulster, the Donn Cuailage, and the mighty white bull of Connacht, the Finnbennach. A hundred warriors could stand in their shadows; fifty youths could play games across their backs. Each bulled fifty heifers every day, the calves born out of their mothers the next.’

The three sisters sharpened three stakes of rowan, pressed point against skin and three drops of blood fell on the frozen ground. The hungry hound lapped it all up.

‘How did it all begin?’ asked the oldest midwife.

‘With the birth pangs,’ said the youngest one. ‘When men lost their sense of wonder and stopped evoking the old gods, those who had once been worshipped retreated into the hills and the hedgerows.

‘There was a farmer whose wife had died. He knew about crops and cattle, but to care for the four boys she had left behind, now, that was a different kind of task. The farmer was handsome and women liked him well enough, but none were eager to enter a dead woman’s bed so soon.

‘Then, one day, a quiet woman slipped into the house. He could not remember her knocking or saying good day. Just one day there she was, sitting by the hearth staring into the fire. Nothing was said. He nodded. She nodded back as if this had always been their custom. She put the bread on the table and no questions were asked about who she was or where she was from. He was not a curious man. And anyhow there was work to be done and children to be fed, and he knew never to look a gift horse in the mouth. Now on the farm, everything was done quicker and better than before. The cow’s milk tasted creamier and the farmer grew richer. Then one night as easily as she had come into the house, the farmer found she had slipped into bed beside him. Lovemaking was as quiet as everything else she did and as finely judged.

‘He awoke to find her place in the bed empty and cold. He called for her. She did not come. He wrapped the blankets around himself and opened the door to the outside world. There on the hill, under the stars, he saw her. Yoked to the plough, she was turning the earth as easily as a woman turns her head. Then she saw him and slipping out of the harness and moving with the swiftness of a steed, she stood before him and spoke. “Promise to tell no one what you have seen. Promise.”

‘He promised.

‘One day, word came from the king; an invitation to the yearly horse fair.

‘“Don’t go,” she pleaded. “My time is near. The new ones will soon be coming.”

‘“I won’t be gone for long,” he said. “I cannot refuse the king.”

‘“Then remember your promise,” she said. “Mention me to no one.”

‘“Of course,” he said. “I promised.”

‘“Yes you did,” she said.

‘So he went to the fair and watched the sport and the king’s horses won every race. “Nothing could beat those creatures,” said the man standing beside him. The farmer said, “Even my wife could run faster than that.” The man turned to the one next to him and repeated the words. And he to the man next to him and these words were carried by the crowd to the ears of the king.

‘The farmer tried to take back what he had said, but the king’s men were already on their way to fetch his wife.

‘There was to be a different kind of race.

‘“I see you are carrying a heavy handicap,” said the king when she was brought before him. The woman pleaded that the contest be put off until after the birth. He shook his head. She appealed to the crowd. “Help me,” she cried.

‘They turned away.

‘“Kill me instead,” the farmer begged, but it was too late for that. The race was on. At the start the horses strained while she stood still. Then they were off. Neck and neck they ran, a step, a stride, a gallop, a blur of brown and white, nostrils flaring, snorting in the air and with one last effort she crossed the line first and there she brought into the world a boy and a girl. Then she began to change.

‘“Call yourselves men? You who watched and did nothing! I curse you.” She reared up, her limbs now a hail of hooves clattering down over their heads. “You who stood there and said nothing! I curse you. Dumb animals! I curse you.” Now the bit was between her teeth. “Know who I am! I am Macha!” screamed the nightmare. “You who once fell on your knees before me and my kind! Who ride our backs without a thought for all we have to bear! I curse you, the men of Ulster, to suffer the birth pangs of a woman whenever you are vulnerable and need help. I curse you for nine generations.”