6,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

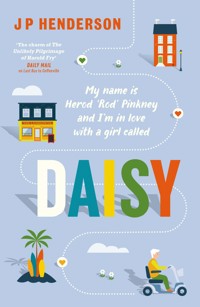

MEET DAISY. A PICTURE OF GRACE AND DIGNITY. MEET HEROD. A... DISAPPOINTMENT Written in his own words, and guided by a man who collects glasses in a local pub, this is the story of Herod 'Rod' Pinkney's search for Daisy Lamprich, a young woman he first sees on a decade-old episode of the Judge Judy Show, and who he now intends to marry. When Daisy is located in the coastal city of Huntington Beach, California, he travels there with his good friend and next-door neighbour, Donald, a man who once fought in the tunnels of Cu Chi during the Vietnam War and who now spends most of his time in Herod's basement. Herod is confident that the outcome will be favourable, but there's a problem... Will the course of true love ever run smoothly for this unlikely hero? A funny and touching story of an improbable and heart-warming quest to find true love, Daisy is perfect for fans of The Rosie Project and Eleanor Oliphant is Completely Fine.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

PRAISE FOR J P HENDERSON

‘There is heartbreak… black humour… and the charm of The Unlikely Pilgrimage of Harold Fry’ – Daily Mail on Last Bus to Coffeeville

‘Exceptionally good… the characters and plot are fantastic and I really couldn’t praise it enough’ – Bookseller

‘A fascinating and poignant novel’ – Woman’s World

‘The shimmering humour and life values Henderson explores are certainly something you wouldn’t want to miss’ – The Star Online

‘An amiably weird take on family life’ – Daily Mail on The Last of the Bowmans

‘A funny road trip story… but this brave debut novel also tackles sensitive issues and does so in a confident manner’ – We Love This Book

‘Deftly handled with an offbeat humour and a deal of worldly compassion’ – Sunday Sport

‘J Paul Henderson is someone to watch out for’ – The Bookbag

‘I found myself laughing out loud with the characters. I really enjoyed this story’ – Book Depository

‘A wonderful cast of eccentric people in the best tradition of old-time American writers like Capote and Keillor. I was enthralled throughout and recommend it to anyone who wants a feel-good read’ – New Books Magazine

‘One of the best feel-good books I have ever read!’ – culturefly.co.uk

‘There were some bittersweet moments, some strange moments and some outright funny moments… a lovely, surprising read’ – Novel Kicks

‘Laugh-out-loud funny’ – Reviewed The Book

‘An interesting delight… a brilliant debut’ – Our Book Reviews Online

‘It’s rare to find a first novel that has as sure a touch as this one, with the writing being a combination of Bill Bryson travelogue with humour from James Thurber and Garrison Keillor *****’ – Goodreads

‘If The Hundred-Year-Old Man Who Climbed Out of the Window and Disappeared was a book you enjoyed then I’m surethis book will delight and entertain you just as much’ – Library Thing

‘This is a book well worth reading *****’ – Shelfari

‘Overall I thought the book flowed beautifully and I thoroughly enjoyed it. There will inevitably be comparisons with The Hundred-Year-Old Man – and I’m certain that if you enjoyed that book you will love this one too *****’ – Goodreads

‘The black comedy mixed with a bittersweet and compassionate drama frequently reminded me of the late, great David Nobbs in style’ – Shiny New Books

‘There’s a rich vein of surreal black comedy throughout The Last of the Bowmans’ – The Bookbag

‘A quirky story using black humour to help us feel connected to and to understand events that we could all at some time have to face’ – Library Thing

‘This was a gorgeous little story… you will not want to stop reading’ – Goodreads

‘This is an enthralling tale full of eccentric characters whose stories are cleverly woven together’ – Waterstones

’Tis better to have dreamt and woken up

Than never to have dreamt at all

ALT (alt)

The Start

In my opinion, the world can be divided into two types of people: one happy to talk about themselves, and the other not. I belong to the latter category.

Allow me to introduce myself. My name is Herod S Pinkney and I’m in love with a girl called Daisy Lamprich.

I think that’s enough to be going on with.

7 June 2019

I showed the page you’ve just read to my agent, who collects glasses in a local pub called the Lansdowne. It’s a short page, but it took me a long time to write. First words are important.

He read the typed sheet and nodded his head slowly. It was an interesting start, he said, but indicated that I would have to be a lot more forthcoming if I wanted a publisher to take an interest in my story.

‘The reader wants to know about you, Rod, and what makes you tick,’ he said. ‘And it’s too soon to start talking about Daisy. They’re not going to take an interest in her until they’ve taken an interest in you. You have to hook them and reel them in; get them to invest in you as a person.’

We talked a while longer, but then the pub got busy and the landlord told him to get busy.

‘Talk to the cripple in your own time,’ he said.

You can gather that the landlord isn’t a nice man, and if it wasn’t for my agent working here I wouldn’t give him my business. And it’s not as if I am a cripple. Not everyone who drives a mobility scooter is an invalid.

I finished my drink and drove the short distance home. I live in a quiet street in Battersea, not far from the park, and it’s been my home for some years. It’s an end-terrace house, four storeys high since I had the basement dug, and desirable in every way. The front and side walls are covered in plants – living walls that make up for the small gardens to the front and rear of the property. I got the idea from the Athenaeum Hotel on Piccadilly, and even got the man who did their walls to do mine. The odd thing about him was that he didn’t like heights. In the time he worked at my house he had two panic attacks and never smiled once. Edmundo takes care of the walls now. Edmundo takes care of most things.

Once settled, I poured myself a small whisky and mulled over what my agent had said. His name is Ric, by the way, though for the life of me I can’t remember his last name. It’s foreign sounding and full of consonants that don’t usually sit together, which in his walk of life he considers an advantage.

‘It makes me stand out from the crowd, Rod – a bit like your name makes you.’

I suppose he has a point, though personally I don’t like my name and I’m happy to be a part of any crowd. I think it’s good to fit in. That’s why I ask people to call me Rod rather than Herod these days, though I only felt free to do so after my parents died. I suppose this would be a good time to tell you about them.

I think this is what Ric would want me to do.

Continuation 1

Pinkney Industries

My father was George Pinkney, the founder of Pinkney Industries. He was a burly man with a wide neck and size eleven feet. His jaw was square and his ears were flat to his head, as if pressed there by a laundress. He also had a thick moustache that hung over his top lip and he greased his hair to the point of waterproofing his head. He wore a suit and a tie every day of his working week, but on weekends and holidays favoured cravats.

My father was self-made and never tired of telling people this. I worked for him while he was alive, but I have little idea how he made his money. In truth, I think my father kept me in the dark intentionally. I got the impression he didn’t like me, and he was forever telling me how much a poor substitute for Solomon I was. And that’s what I was in the family: a substitute for a dead brother who’d shown more promise in his little finger than I did in my entirety – or so my father kept telling me.

Solomon died on his sixteenth birthday after diving into the shallow end of an outdoor swimming pool. If he was as bright as my father said he was, then you have to wonder why he failed to realise that the diving boards were at the other end of the pool for a reason. I kept this thought to myself, though. Life was hard enough just being a disappointment.

And because I was a disappointment to my father, I was also a disappointment to my mother. It could have been no other way. My mother worshipped my father, and it was this quality that endeared her to him. He expected no less of a spouse: a partner who would accede to his whims and decisions without question.

Most people considered my mother to be a beautiful woman, but I never saw this. Her full lips were always tightened when she spoke to me and her eyes invariably narrowed, and the smile that supposedly lit up the salons of London was never once in evidence. According to my Uncle Horace, who was married to her sister Thelma, my mother could have had her pick of London’s eligible men but had chosen my father for his August nature. (I never quite understood this, because my father’s birthday was in November.)

If my mother had wanted more children than the two she gave birth to, then she never said. It certainly wasn’t something she would have confided in me. My father, however, had made it clear that he wanted only one child: a son he could mould in his own image and entrust with the family empire. Solomon was that child, not me. I was supposed to be another Solomon, but I wasn’t.

I was born eighteen months after my brother died. By the time I was three, my father had already decided that I was never going to be another Solomon. For one thing, he said my face was too fat, and he was also annoyed by my sedentary nature.

‘Every time I come into this house, Herod, you’re sitting on your damned backside,’ he’d say. ‘What’s wrong with you, boy? Do you want your buttocks to grow to the size of your face? Now give me three laps!’

(We had a large lounge.)

When I looked to my mother for support, she simply told me to do as my father bade, adding that Solomon had only sat down on a chair for meals. I never once believed this, but Solomon, though ever-present – his sports trophies and awards adorning the shelves and the walls of the lounge – was never there to question.

I started to sit in secret, whenever my parents were out of the room or, better still, out of the house, which happened often. I had to be careful around the cleaner and the babysitters, though, because my father gave them strict instructions to keep me on the move and to report back to him if they ever caught me sitting on a chair or stretched out on a sofa. My father was a firm believer in the power of money to make others do his bidding, and every time they informed on me they were paid a bonus.

The safest place to sit was the toilet, and this room became my home away from home when I lived at home. No one bothered me there, and I used to slip the bolt on the door to avoid being caught unawares, even though this was against the rules. My happiest times as a child were the hours I spent sitting on a toilet seat, reading a comic or just daydreaming – which was something else my father disapproved of.

Consequently, when my parents sent me away to boarding school at the age of seven, I was as happy as Larry. The school was situated in a small town in Wiltshire and discouraged parental visits during term time. This suited me fine, but what particularly pleased me was the school’s expectation that I would sit in a classroom for most days of the week, and on wooden seats no less comfortable than the one in my parents’ toilet. Learning became a pleasure, but for probably the wrong reason.

Although it was impossible to avoid all sport in a school dedicated to building character on the playing field, I was excused from outdoor games in the spring and summer months because of my allergy to grass and tree pollens that occasionally gave rise to severe asthma attacks. The headmaster allowed me to substitute chess for the more physical games at this time of year, and I was much happier proclaiming my school spirit from a seated position.

I wasn’t much good at chess and I used to lose matches to pupils much younger than me, but I never minded losing. Evidently, this was another quality that distinguished me – and not in a good way – from my late brother, who had also attended the school.

Teachers were never shy of telling me how much a shadow of Solomon I was, who, they said, was also more gifted than me scholastically. I wasn’t stupid, but I did suffer from a form of dyslexia that wasn’t diagnosed until after I’d left school. It’s not so bad now, and with spellcheckers it’s no longer a concern. I occasionally get words and numbers muddled but not often enough for it to be a problem, and as I no longer work for a living it hardly matters.

On the whole, my schooldays passed without incident and I made some good friends. The only thing I was teased about was my name: Herod.

‘Why are you named after the man who killed all those children?’ I was asked over and again. ‘You know that Herod tried to kill Jesus, don’t you?’

As a matter of fact, I didn’t. Despite my father favouring biblical names for his sons, the Bible itself was banned from the house and not once did he or my mother take me to church. He was an atheist, I think, and if he was an atheist then so too was my mother. I think that’s why religion came to interest me: if my father disbelieved in God then there was every cause for me to accept Him – even if it was only to annoy him and avoid the risk of running into him in the afterlife.

It was during a forced march along the Thames Embankment one school holiday that I asked him about my name. Why was I named after an ancient king who’d slaughtered hundreds of small children and tried to kill Jesus? And why the middle initial that seemingly didn’t stand for anything? Why Herod S Pinkney?

‘Because Herod was a great man,’ my father answered, ‘and I was hoping that by giving you his name, his qualities might rub off on you. And you can forget all that nonsense about him slaughtering hundreds of small children because that never happened, and if, for the sake of argument, it did happen, then there were no more than twenty put to death. There’s no historical evidence to support such a notion, and if he didn’t kill Jesus… well, that was his one failure.

‘What you need to know about King Herod is that he was ambitious, ruthless, and one of the greatest builders of all time. He knew how to get things done and he wasn’t prepared for anyone to stand in his way – not even his own family. If you want to succeed in life, Herod, then you need to have his qualities, especially when you have such a fat face.’

I used to get tired of my father telling me I had a fat face. I wasn’t the only boy my age to have chubby cheeks, and I certainly don’t have those cheeks today. In fact, and though I don’t like to blow my own trumpet, most people consider me a handsome man, and I have no reason to doubt them.

But I’m digressing, which I’m not sure Ric would approve of.

‘What about your middle initial, Rod? Why the “S”?’ I can hear him asking.

Well, it turned out that the ‘S’ stood for Solomon, but my birth certificate would only reflect this if I turned out to be like my brother, which, my father said, seemed increasingly unlikely.

‘I named Solomon, Solomon, because of his knowing face,’ he said. ‘He looked wise beyond his years even the day he was born, as if he’d been thinking about things the entire time he’d been inside your mother’s womb. I couldn’t have wished for a more erudite looking boy.’

Again, I was reminded of the way Solomon died and I couldn’t but wonder about his supposed wisdom. Apart from – well, actually, including his death, come to think of it – my older brother got all the breaks. Me, I got none. But at least I lived to tell the tale.

So life went on but nothing really changed. I did okay at school but not well enough to be accepted by either Oxford or Cambridge, and because my father wasn’t prepared for a son of his to go to a redbrick university, I ended up going to work for him at Pinkney Industries.

Even though my father and I lived under the same roof, we went to his offices separately, him by car and me on a bicycle or by public transport. It was all right for him to sit in comfort, but not me. I had to use my legs.

And all the jobs he gave me at Pinkney Industries involved movement. If I wasn’t working in the mailroom, delivering letters and packages to offices in a five-storey building with no lift, I was working for what these days would be known as a facilities department and tasked with rearranging office furniture every time my father decided to restructure the company, which was often and mostly, I suspect, to keep me busy.

I thought for a time that by starting me at the bottom, my father’s aim was for me to learn all aspects of his business before promoting me to a position of greater responsibility, but in thinking this I was mistaken. My father’s intention was for me to remain at the bottom in perpetuity.

Considering my education, I suggested over dinner one evening that I might be of more service to him doing something other than working in the mailroom and facilities departments, and surprisingly he agreed. He told me a vacancy had arisen in one of his American interests and that the job would be mine if I was willing to travel to the United States. I jumped at the chance, but in retrospect I should have known better than to accept his munificence at face value. The job in question turned out to be a deckhand on a Mississippi towboat, and it was the worst six months of my life.

When I returned from America I didn’t have an ounce of fat on my body, and even my father had to admit there was less flab on my face than usual. And what was my reward? I was sent back to the facilities department!

If my father hadn’t died unexpectedly from a heart attack, I would have probably been moving desks and changing light bulbs for the rest of my working life. As it was, he did die unexpectedly from a heart attack and was found slumped over his desk by the secretary who brought him his afternoon coffee.

I wasn’t summoned to the scene because no one in the building knew I was his son. He’d never told anyone of our relationship and I’d never been allowed to mention it for fear, my father said, of people misinterpreting my employment as nepotism. During the time I worked at Pinkney Industries I was known as Brian Beasley. All things considered, I think most people would have construed my appointment as a punishment rather than an unfair leg-up, but, as always, I did as directed and said nothing.

I only heard the news of my father’s death once I’d returned home and found my mother on the kitchen floor wailing. She was curled up in a foetal position, and it took time to unravel her and get her to a sitting position, and even longer to quieten her moaning. And when she did stop sobbing, she started to scream at me.

‘Your father’s dead, Herod, and it’s your fault! He didn’t die of natural causes, he died of disappointment: disappointment in you!’

It wasn’t a promising start to the new family dynamic.

It’s difficult to explain how I felt when my father died. No loved-one had passed away, but a familiar landscape had changed, as if a building I’d passed every day of my life had suddenly been demolished. There was a void, neither welcomed nor unwelcomed. That’s all I can say on the matter.

I didn’t cry then or at the funeral, which was large and unnecessarily showy, and though I tried to console my mother during the service, she pushed my arm away. There seemed to be no pleasing her that day: everything I did or said was somehow wrong. And over the weeks that followed, things between us didn’t improve. She shut herself in her room and refused to talk to me and only emerged to meet with my father’s solicitor or the financial director of the company.

One night I knocked on her bedroom door, and when she didn’t answer I entered hesitantly. My mother was staring into space and ignored my intrusion.

‘Mother,’ I said. ‘I’m worried about you. I want to support you but you won’t let me. What can I do to help?’

She didn’t turn or look at me, but in a voice that was both cold and monotonic replied that I could help her most by leaving the house and going to live with my Aunt Thelma.

‘And don’t even think about taking the car,’ she added somewhat unnecessarily.

I didn’t even know how to drive a car.

And so I went to live with my aunt. Aunt Thelma was my mother’s sister who lived in Vauxhall, not far from my father’s offices, and whose husband, Horace, managed a branch of Barclays. It was him who answered the door when I knocked, and the first thing he asked was what I was doing there with a suitcase. Before I had time to answer he shouted the same question to his wife. My mother, it turned out, had failed to mention my arrival to them.

The most I can say about my time with Aunt Thelma and Uncle Horace is that they were civil to me but that it was always a relief to leave their house on a morning and cycle to work, where I continued to report to the facilities department. Every day I expected to be summoned to the boardroom for a reassignment of duties, but three weeks went by and still nothing happened.

And then, the day before my birthday, Aunt Thelma told me that my mother had phoned and asked that I return home the following evening and join her for a celebratory meal. I was touched that my mother had remembered my birthday at such a sad time in her life, and I looked upon it as an omen: a new beginning for the two of us, and possibly news of my future at Pinkney Industries.

After finishing work the next day I went back to Aunt Thelma’s and quickly changed into my best suit, and then, as it was my birthday, I hailed a taxi. I knocked on the door of my mother’s house to show respect, and then opened it with my key. There was the sound of loud music, but the needle had stuck in a groove and it was difficult to make sense of what was playing. I called my mother’s name (which was Mother, just as my father’s name had always been Father), and lifted the needle from the vinyl disc spinning on the turntable. It was a recording of We’ll Meet Again by Vera Lynn, which had been one of my father’s favourites.

There was no sign of life in the downstairs rooms. The dining table hadn’t been set and there was no hint of any food having been prepared in the kitchen. In short, there was no sign of the celebratory meal I’d been invited to.

I was about to climb the stairs when I noticed the French windows wide open. It was midsummer and the evening was warm, and it occurred to me that my mother might have arranged a table in the garden and that I’d find her there. In thinking this, I was half-right and half-wrong. There was no food on the garden table as I’d expected, but I did find my mother’s body swinging from the branch of a large oak tree.

My mother’s death, although obvious to me as self-destruction, was only ruled a suicide once the cleaner found a note under her pillow the following week. Until then, the police had been working under the assumption that it was me who’d hanged her from the tree, if for no other reason than to teach her a lesson for not cooking me a birthday meal.

I learned later that their suspicions had first been aroused when they arrived at the house and found me sitting in an easy chair eating a ham and cheese sandwich and seemingly unmoved by the discovery of my mother’s body. My explanation, that I hadn’t eaten lunch that day and was feeling faint, cut no ice with them.

‘How can anyone think of their stomach at a time like this?’ one of the policemen commented loud enough for me to hear.

They dug deeper and decided that I was a young man with a chip on his shoulder; a son resentful of parents who’d denied him the entitlement he deserved. My father, they noted, had placed me in a low-grade position within his company and left me there to stew, while my mother, believing me to have been a contributing factor in her husband’s death, had banished me from the house and sent me to live with an aunt who, as it transpired, also wasn’t enamoured of me. They argued that I had everything to gain from her death and nothing to lose, and that it was me, rather than my mother, who had placed the recording of We’ll Meet Again on the turntable in an attempt to divert attention from myself and focus it on her frail mental disposition.

Honesty in such circumstances, I learned to my cost, is not to be encouraged. When asked if I’d loved my parents, I’d replied that I didn’t think my parents had loved me, and when pressed on the point I had to admit that I probably hadn’t. It didn’t, however, make me a killer, I added.

‘That’s for us to decide,’ the man leading the investigation replied, something they were only dissuaded from doing after my mother’s letter came to light.

The letter was handwritten in green ink and addressed to me. She started by talking about Solomon and what a wonderful son he’d been, and then she listed the many ways in which I’d disappointed her and my father. In particular, she thought it a disgrace that I still couldn’t spell properly after all the money they’d spent on my education.

She then came to the crux of her anguish: the death of my father. He’d been the love of her life, the reason for her being, and without him there was no point to life. She rued the fact that she hadn’t been burnt alive on a pyre after he’d died – as they did in some parts of India (where my father also had interests) – and that such short-term agony would have been as nothing compared to the suffering she now endured. She was done with this world, done with me and done with Pinkney Industries. She was off to find George, her dear departed husband, who, she believed, couldn’t have strayed all that far in the short time he’d been dead.

My mother’s suicide wasn’t unconscionable in itself, but choosing my birthday as the occasion for her death, and for me to find her body, was.

If my parents had shown me love while they’d been alive, and I’d been asked to choose between their affection and their money, then I would have gladly opted for their affection. But they didn’t, and so in their absence I accepted their money. Overnight, I became a rich man.

Well, I say overnight, but it wasn’t quite as simple as that. For one thing, there was a lot of paperwork to sort out, and for another, my Uncle Horace contested my mother’s will, which had left everything to my late brother, Solomon.

Why her will had never been updated was a mystery to all, but that it hadn’t was a stroke of luck for me, as I suspect she’d have preferred her estate to have gone to an animal shelter than pass to me. As it was, the house, her inherited savings and Pinkney Industries passed into my hands, and the next time I walked into my father’s offices I was fêted like a king:

‘Hello, Brian. What are you doing here?’

*

It quickly became apparent – both to me and my fellow directors – that I was out of my depth, and that under my tutelage the future of the company was anything but secure. I’m not trying to sing my own praises here, but I think I recognised this fact before they did.

I stuck it out for a month and then asked the financial director to step into my office. His name was Robert Green and he’d taken me under his wing during the short time I’d been there and shown me kindness. It was him, in fact, who’d mentioned that I might have dyslexia; certainly he could think of no other explanation for my strange memos.

We sat down and the secretary brought us coffee. He was about to take a bite of his biscuit when I asked him the question that had been puzzling me ever since I’d arrived at the offices.

‘What is it that Pinkney Industries actually does, Robert? What do we manufacture?’

It turned out that we didn’t manufacture anything, and that to his way of thinking the company’s name had always been misleading. The company owned property, he said, made investments, bought and sold intangibles, and had as many interests overseas as it did in the United Kingdom.

‘Without being condescending, Herod, it’s a bit complicated.’

There was no kidding me there.

After more discussion we decided that it would be best – both for me and everyone whose livelihoods depended on Pinkney Industries – if I stood down as CEO and the company was divided into manageable chunks and liquidated. It was important to me that no employees lost their jobs in the transition – especially in the mailroom and facilities department – but although Robert couldn’t guarantee this, he thought there was a greater chance of people losing their jobs in those departments if I continued to run the company.

We shook hands – his more capable than mine – and that, I’m afraid, was the beginning of the end for Pinkney Industries. That my father and, by default, my mother might be turning in their graves at this moment, concerned me not at all.

And then the day came when Robert invited me to the office and handed me a cheque for eleven million pounds.

‘The world’s your oyster, Herod,’ he said. ‘Do you have any travel in mind?’

I told him I had, and that I was hoping to spend a few days in Bournemouth.

Robert walked with me to the car park and was surprised to see my bicycle standing in my father’s reserved space.

‘I thought you’d have driven here in your father’s car,’ he said.

I explained that I was having a few problems passing my driving test and had, in fact, already failed it twice: once for going through a No Entry sign, and another time for mistaking a line of parked cars for an active lane of traffic. The first failure I could understand, but the second I put down to the examiner being in a bad mood. It still jars me that he didn’t mention my mistake for a full fifteen minutes, which was half the allotted time for the test.

Robert told me not to lose heart and I took his advice. A year later, and after only three more attempts, I got my licence.

Eleven million pounds was a lot of money, far too much for one person, and I decided to give half of my inheritance to a deserving cause. I wanted to make a difference to the country and to do it with one stroke: do something that would tackle poverty and improve the lives of those in need, alleviate suffering in all its forms and ensure that all citizens had access to good schools and a free health service.

I thought things over for a month, turned them in my mind again and again, and then, after breakfast one morning, I made the decision that I believed any person in my position would have made: I wrote a cheque for five and a half million pounds and donated it to the Conservative Party.

I then had to make decisions about my own life: where I would live and what I would do. I had no attachment to the family home: I felt like an uninvited guest there, just as I had when I’d lived there with my parents. The house held no fond memories and, though the oak tree had been cut down, I could still sense my mother’s body swaying from its invisible branch. It wasn’t a question of whether I would stay but when I would leave, a matter that was resolved three months later when I stumbled on the property I now occupy.

I’d been visiting Miss Wimpole that day, a dyslexia therapist whose practice was in the borough of Battersea. Her rooms were several streets from where I live now but a good distance from the bus route, and it was while I was walking from the bus stop to her house that I passed the For Sale sign in its garden.

I already liked the area from past visits to Miss Wimpole, and as she’d intimated that we’d be seeing each other for at least three years, I thought it sensible to move closer to where she lived. I’ve always thought that convenience has a lot to offer in life.

Before I start telling you about the house, however, I should probably finish telling you about my therapist. Again, I think this is another thing Ric would want me to do.

Miss Wimpole was in her early sixties but looked older, as if a strong tailwind was blowing her through life. She was a spinster and wore cardigans and thick woollen skirts, and she had a cat called Pedro that never left the room. She’d been recommended to me by a general practitioner, and she spoke to me as if I was six – probably the age when most of her patients first visited.

‘Well, dear, what makes you think you have dyslexia?’ she asked me on my first visit.

I told her that I wasn’t sure if I did or didn’t because I’d never been able to find the word in the dictionary, but that Robert thought I had and that my mother had mentioned my inability to spell in her suicide note.

‘Oh dear, dear, I’m so sorry to hear that,’ she commiserated.

She then gave me some tests and decided that I was dyslexic – though by no means the worst case she’d encountered in her years of practice.

‘But this doesn’t mean you’re stupid, dear, if that’s what you’ve been thinking.’

I told her that I hadn’t been thinking this, and that until she’d mentioned it the thought had never crossed my mind.

‘Well, dismiss it immediately, dear,’ she said, ‘because you’re not stupid: you just have a disability.’

The word disability unnerved me more than the word stupid, and Miss Wimpole noticed my concern. She patted me on the knee and gave a sympathetic smile.

‘We don’t have time for self-pity, dear: we have important work to do!’

And for the next three years we worked on what she called phonological skills, and though the underlying problem remained when we parted company – she retired from practice and went to live with her widowed sister in Cornwall – the degree of my symptoms had decreased considerably.

During the time I visited Miss Wimpole, the house in Battersea became my life. Although its structure was sound the interior had been sadly neglected, as if the previous owners had been blind to its decay. I didn’t do any of the work myself, but instead hired a contractor to oversee the renovations. I told Mr Axelrod – a man in his fifties, and whose forearms were the size of my thighs – to simplify the house and to make it spacious and warm, and he succeeded beyond my expectations.

The wall dividing the kitchen from the dining room was demolished and a large glass double door was inserted into the wall separating the newly enlarged room from the lounge. The existing cast-iron radiators were replaced, installed for the first time in the upper rooms, and the fireplace chimney unblocked and swept. Lastly, though by no means least, the walls were stripped of their flowery wallpaper, completely re-plastered and painted in plain colours.

It was a year before the house was fully transformed, and during these months I lived in a single room, first on one floor and then on another, its changing location determined by the workers’ schedule.

I might add here that living in a house under refurbishment is no easy matter, and it certainly hadn’t been my intention to do this. My parents’ house, though, had sold faster than anticipated, and to fit in with the new owner’s timetable I was obliged to vacate the premises and fall in with the contractor’s.

It might be puzzling that a man of my wealth, whose fortune had recently been increased by the sale of a substantial property, had chosen to squat in a building site rather than move to somewhere like the Ritz. It also puzzled Mr Axelrod, who asked me one day if I was hiding from someone.

The answer, however, is a simple one: I couldn’t get used to the idea of being rich.

I’d never had money before, and the small wage paid by Pinkney Industries had barely covered the board and lodging demanded by my mother, and later my Aunt Thelma. I’d learned to scrape by, to value the pennies, and I’d witnessed my colleagues in the mailroom and facilities department doing the same. I didn’t know how a man with money was supposed to behave, and so I chose to behave like a man without money, favouring public transport over taxis and small cafes over fancy restaurants. For me, this was the attraction of Battersea, which was a mixed area rather than a preserve of the wealthy. Its humdrum nature suited me, and I thought I’d fit in here.

The workmen left me a polished shell that now had to be furnished. Just as I’d placed the renovations in the hands of one person, I now gave responsibility for its furnishing to another.

Trudy Barnes was the wife of one of the plasterers, and I had no reason to doubt the recommendation of a man who’d smoothed my walls so beautifully. She was a dainty little thing, no more than five feet tall, but she scared the living daylights out of me. I supposed it was her artistic temperament that made her so prickly, though it was a disposition I’d never before associated with soft furnishings. Anyway, she got the job done, and although her choice of drapes was a touch on the garish side, I was pleased that she’d used the same carpet throughout.

I learned later, from the butcher in fact, that Trudy was colour-blind, and he supposed that this might be a drawback in her line of work. Later still, however, I heard from someone else that the butcher held a grudge against Trudy for returning a chicken she’d claimed was on the turn, and that I should take his opinion with a pinch of salt. It felt good to have stumbled upon a community where people took such an interest in each other.

I could live with Trudy’s choices as they were, though, and over time, and once my parents’ furniture was installed in the house, the curtains quietened to no more than a loud hum.

I didn’t take all my parents’ furniture, only the pieces I liked, but among them were the chairs and sofas I’d always been discouraged from using. The only keepsakes I held on to were photographs of my parents and Solomon – though more, I suspect, to prove to others that I hadn’t grown up in an orphanage than for any sentimental reasons – and a selection of my father’s cravats, which I’d always admired. I’m wearing one now, as a matter of fact: it’s blue with white polka dots and made from the finest silk.

Next, I started to think about a job. I didn’t need one, of course, but I was hoping that a pursuit of some kind would allow me to meet new people and, if all went to plan, make friends.

I’d lost contact with most of my old school mates – many of whom had gone on to university and now worked in the professions or had joined family businesses – and my social life was at best threadbare and had been so ever since I’d gone to work for my father. My wage in those days had been no more generous than that paid to any employee who worked in the mailroom or facilities department at Pinkney Industries, and certainly hadn’t afforded me the luxury of mixing in the social circles of former friends – something I learned as a matter of course after accepting an invitation to meet with Gerald Smithson one Saturday night.

Although a year older than me, Gerald had also been a member of the school’s chess club, and though we’d never been best friends, we’d always enjoyed each other’s company. I bumped into him on Regent Street one day after hand-delivering a small package to an office located on one of its side streets, and it was difficult to know which of us was the more surprised. He was on his way to meet a client for lunch and running late, but suggested I join him and Charlie for a ‘glass or two of the old vino’ that Saturday night and make up a foursome. I happily accepted his proposal, and when I returned to the office I asked Trevor if he was free that evening.

Trevor also worked in the mailroom and was about the only person in Pinkney Industries I was on good terms with. He was a keen snooker player and I’d accompany him to a local hall some lunchtimes. I never played the game myself – it involved too much standing for my liking – but I was more than happy to sit on a chair and watch him pot balls while I ate my sandwich.

Unfortunately for the evening ahead, Trevor had assumed that the foursome I’d mentioned related to a game of snooker, and when he emerged from the tube station on Kensington High Street that night he was carrying an uncased cue. My expectation for the evening was of four men having drinks together and shooting the breeze – the way we used to on the towboats – but in thinking this I’d been as mistaken as Trevor for supposing that we’d be shooting snooker balls.

It turned out that Gerald’s friend, Charlie, was a girl, and that Gerald had been expecting me to arrive with another girl and not some ‘greaser holding a pool cue’, as he later put it. I had a bad feeling about the evening as soon as we walked into the wine bar and the management insisted on Trevor leaving his snooker cue in the umbrella stand by the door. And then, after we had joined Gerald and Charlie at their table, it quickly became apparent that neither of us had enough money for more than two drinks if we weren’t to walk home that night.

Charlie, whose full name was Charlotte, was a pretty girl but distant, and for most of the evening she remained silent. Trevor, however, who would have done better following her example, showed no such reticence and spoke at length on the finer points of snooker, even after Gerald had made it clear to him that he wasn’t interested in the game.

‘That’s because you don’t understand it,’ Trevor had countered before continuing.

It was difficult to get a word in edgeways with Trevor there, and it was often frustrating. When Gerald mentioned that he was an actuary, and I said that I didn’t know what that was, Trevor explained that an actuary was a man who made watches for a living.

‘Is that right, Gerald?’ I asked, surprised by his choice of vocation.

Gerald said that it wasn’t, and that anyone who thought this had probably been hit over the head with a snooker cue too many times. He compiled and analysed statistics used to calculate insurance risks and premiums, he said, and explained that Trevor had confused the word with Accurist, which was the name of a watch. He then pulled up the sleeve of his shirt and showed us his wristwatch, which proved to be just that: an Accurist.

‘I was half-right, then, wasn’t I?’ Trevor said.

Nothing jelled that evening, and I was relieved when Gerald and Charlie left for the restaurant they’d booked.

‘We reserved a table for four,’ Gerald said, ‘but I don’t think they’ll mind if I change the number. I’m one of their best customers.’

I still see Gerald from time to time, but I’ve lost touch with Trevor. Two weeks after our night out together, he was sacked from Pinkney Industries by no other person than my father, who’d found him asleep under his desk. To this day I have no idea why Trevor chose this particular location, other than that the carpet in my father’s office had a thicker pile. Sometimes I watch out for him on television when they’re broadcasting a snooker competition, but so far I haven’t seen him.

Anyway, now that I had decided a career was the likeliest avenue to a social life, I was still faced with the problem of deciding its nature, and it made sense to seek the advice of a professional.

From my time trudging to and from Pinkney Industries, I was aware of an employment agency on Stamford Street – in the borough of Lambeth, just south of the river – and it was here that I made an appointment to see Adrian Crusher, its chief consultant.

Mr Crusher was a portly man in his early forties and he wore a distinctive dark, pinstriped suit. His hair was thick and black, and his shoulders were speckled with dandruff that he brushed away with his hand from time to time.

‘I know all about it,’ he said, when he saw me looking at the flakes.

I blushed when he said this and started to apologise, but he cut me short.

‘Forget it, Mr Pinkney,’ he said. ‘Catherine the Great suffered from dandruff, and if it was good enough for her then it’s no skin off my nose.’

I was impressed by his skilled use of words and I asked him if he was a writer. He said that he wasn’t.

Mr Crusher read the handwritten notes I passed him and then scratched his head, causing a further fall of scurf.

‘This is about the oddest employment history I’ve ever read,’ he said, which, to be fair to Mr Crusher, was an accurate description.

Apart from my time as a deckhand on the Mississippi River, I’d worked only in a mailroom and a facilities department, and neither of these situations had seemingly prepared me for the duties of a managing director.