Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: The History Press

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Serie: Folk Tales

- Sprache: Englisch

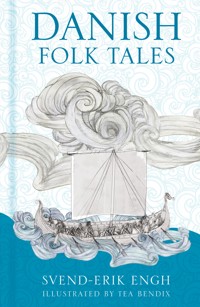

A collection of tales that grew out of the sprawling flatlands, the oozing fjords, the dark forests and the waves that crash on the shores of Denmark. How a Viking ship carried a future king into Roskilde Fjord, how a mermaid's laughter brought fortunes to her fisherman host, how the people of Lolland survived a flood with waves 3m high and how a princess found her freedom in becoming a prince. Experience the history, landscapes, stories and fairy tales brought to life by a storyteller who called this country home for nearly sixty years.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 273

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

First published 2023

The History Press

97 St George’s Place, Cheltenham,

Gloucestershire, GL50 3QB

www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Text © Svend-Erik Engh, 2023

Illustrations © Tea Bendix, 2023

The right of Svend-Erik Engh to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 80399 367 6

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall.

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

Foreword

Introduction

1 Danmark

2 King Skjold

3 Tora and Ragnar

4 Kraka and Ragnar Lodbrog

5 King Lindorm

6 The Two Friends

7 The Fat Cat

8 The Sevenstar

9 The Sledge

10 A Father’s Heart

11 The Princess who Became a Man

12 Three Lessons to be Learned

13 The High Church of Lund

14 The Danish Captain

15 King Christian IV and Jens Longknife

16 Prince Vildering and Miseri Mø

17 The Devil’s Coffee Grinder

18 The Devil and the Blacksmith

19 The Devil’s Best Hunter

20 The Mermaid that Laughed Three Times

21 The Shoemaker’s Boy

22 Three Merry Wives

23 Peder Oxe

24 The River Man

25 Skæve

26 Göran from Sweden

27 The Shoemaker at War

Glossary

Sources

Acknowledgements

FOREWORD

Let me introduce you to Svend-Erik Engh, one of my favourite storytellers. First of all he is a very, very tall man, slim-built and pretty bald. Everything about him seems quite smoothed out till you see the expressive mobility of his face, which is often wreathed in smiles, or open-mouthed in interest and astonishment at what you are telling him. That is Svend-Erik the person, and Svend-Erik Engh the storyteller.

About forty years ago I saw Dario Fo, the Italian storyteller and theatre maker, perform live at the Edinburgh Festival. He came on stage with a scruffy cardigan hanging round his very tall and lean body. He began talking to us in a low key, natural manner. Then gradually his tale of mediaeval priests and rogues took shape, and his body and face began to move with the story. Soon every part of Dario was willowing and weaving, wobbling and occasionally jerking, all to express action, characters and emotions. Yet there was still control remaining at the centre, a cunning identification with the tale that simultaneously used every means at the storyteller’s disposal to share its development.

Svend-Erik is in the great European tradition of Dario Fo’s artistry. He begins in a natural low-key mode till he establishes a genial rapport with his listeners and then he uses his gifts of expression to usher us into the story experience. Moving face and increasingly form, Svend-Erik draws us through the tale with a full gamut of emotions, liberal doses of humour and an undergirding of humane understanding.

This approach to storytelling is firmly rooted in Svend-Erik Engh’s Scandinavian culture, in particular its educational traditions, as inspired by N.F.S. Grundtvig, the great Danish philosopher of poetry and myth. Here is Svend-Erik’s own account of falling into the art of storytelling:

The first story I told was to my students when I was a Folkhøjskole teacher in 1993. It was at a morning assembly and every morning the teacher was supposed to give them a personal message, it could be a film, a book, something from the news, something that that teacher thought could interest the students coming to the school in the morning. It was my debut as a storyteller. It went well. They listened in another way from when I had chosen to read out loud from a book. And when we had lunch together that day I heard my story being retold to some of the students that missed out the morning assembly. No students had ever done that with any of my readings or if I had shown them a film. I was hooked on this thing called storytelling. And since that morning I have told stories in schools, in working places, to people in a park in Copenhagen and, after I moved to Edinburgh, often at the Scottish Storytelling Centre.

Human engagement and communication: here lies the origin and the purpose of Svend-Erik’s art. Yet his grassroots storytelling has been combined with a distinguished contribution to education of all kinds through storytelling. He is an excellent course and workshop leader, who has never lost the teaching gift, or his keen interest in Grundtvig’s philosophy of education.

We are delighted to have Svend-Erik Engh living and working in Scotland, though also pleased to share him with the rest of Britain, with his Danish homeland and with Norway and Sweden, to which he has close ties. Scotland has an integral Norse dimension to its culture and stories, and Svend-Erik’s presence reminds us that we are part of a community of northern nations.

Now in this fine collection of stories, Svend-Erik Engh has dug into his own Danish heritage and art to celebrate its contribution to world storytelling. He explains his approach to making this collection as follows:

This book contains fairy tales and legends, and the term folk tales brings together both of these kinds of stories. As a storyteller, I tell the stories I love. Danish Folk Tales is a collection of my favourite stories.

One of the first fairy tales I told was The Sevenstar, one of the stories in this collection. I had told this story many times to my then three-year-old daughter. And one evening in December we were just home from a trip to the library and the stars were twinkling in the black sky. My daughter looked up at them even before she was completely out of the car and asked me eagerly ‘Where’s the Sevenstar, Daddy?’ I stopped, turned around, looked up, and was blinded by a street lamp. So I told her to walk with me into the darkness. My daughter held my hand tightly as we moved away from the street light, and together we looked up into the twinkling night sky. We were silent for a moment. It felt good to be alive. ‘There it is!’ I said pointing upward. ‘Which one of them is the princess?’ said my daughter. And there we stood choosing which star was which character in the story.

I would love it if you tell these stories out in the world and see what truths they reveal for people. Allow these stories to feed your reality.

The first legend I told was from stories I had found about Caroline Mathilde, the English princess who came to Denmark in 1766 to marry Christian VII, a mad king. She had a serious affair with Johan Struensee from Altona near Hamburg, then a part of Denmark. I lived close to a restaurant called Jægerhytten, the Hunting Cottage, where the two lovers were supposed to have had some of their romantic meetings. The restaurant invited me to tell the legends about their love to their guests. I needed to find some surprising element of the story especially, after the release of a blockbuster film about their love. I found a drawing on the wall of the restaurant of the queen and her lover riding along the coast of Denmark and she was sitting as queens were supposed to, side saddle. But that was not how Caroline rode her horse. I had found many descriptions of how offended people were because Caroline would in fact straddle her horse like a man. Her days in this forest with her lover were a time of freedom, and liberation for the queen. A time when she could be herself.

It is a little different to tell legends from fairy tales. You have to know the history and then you can build your story, create clear images and make the characters real people. And a little unexpected surprise always helps.

It is an honour and a pleasure to introduce new readers and listeners to this outstanding collection of Danish folk tales. But it is an even greater delight to introduce you to Svend-Erik the storyteller. Enjoy!

Donald Smith

Director of Scottish International Storytelling Festival

INTRODUCTION

My hope for these stories in this book is that you will tell them in your way and so they will change and become your stories as I have made them mine.

The book you are sitting with is my interpretation of each story and then with the help of storyteller, native English speaker and my life partner Alice Fernbank it has been translated from my twisted Danish mind to understandable English.

When I look at the stories collected in this book, I can hear the storytellers tell some of the people collecting these stories more than hundred years ago. I feel happy when I, among all the voices of old people, hear a schoolboy named Anders Gregersen, from Sjørslev, Jutland, who has told the story ‘The Devil and the Blacksmith’ to Evald Tang Kristensen. Who was this schoolboy? Where did he hear the story? Telling stories from mouth to heart was a natural part of human life in the days of Anders. It was people’s way of creating some sense in a harsh reality.

So thank you Evald Tang Kristensen, one of the world’s most persistent collectors of stories. You always mentioned from whom you had heard the story when you wrote the story down and published it. The number of stories you have collected is overwhelming and I admire the way that you did it, living in poor conditions with the storytellers and really trying to write down the stories exactly as they were told to you. And you stayed with the storytellers long enough, so they told you everything, including the stories that were full of troubled images or full of words that the people from the nice families didn’t like. In that way you are very different from any of the collectors of stories that are famous now for collecting folk tales: Grimm in Germany, Asbjørnsen and Moe in Norway and in Denmark Svend Gruntvig. You are definitely very different from Hans Christian Andersen, who always puts himself in front of the story and makes sure that nobody can be offended.

So use the stories in this book to be inspired, maybe to visit some of the places I describe. Use the book to be troubled by some of the images and then always remember that the stories were meant to be told and that was a common experience between the storyteller and the listener, so the storyteller could adjust the stories in that moment to the listener’s response to the story. ‘The Princess who Became a Man’ is the story in this collection with the most troublesome images, so when you read it be with somebody that you trust and if the image feels too strong, talk about it, find a way to make it a useful experience for you. And you could, of course, just skip that story and read ‘The Fat Cat’, a lovely little joke – I hope I don’t offend anyone by using the word ‘fat’ about a cat – stories are like that, some are deep and troublesome, some are just plain funny and there are no bigger ideas behind them.

And do yourself a favour and scroll through the illustrations of Tea Bendix, then if you have found something intriguing that has caught your eye, take a deeper look at the drawings. Each of these illustrations has told me a new story. Tea has found a new dimension in the relations between the characters and the landscapes in the stories – just notice the ant in the tree in ‘The Shoemaker’s Boy’. She has spotted something deeper than I have with my simple twisted Danish mind. To work with Tea has been such a joy.

My former father-in-law, Hans Christian Rasmussen, is another story collector and totally unknown for being that. He heard the stories you will find as the last four stories in the book when he was a child in Lolland in the southern part of Denmark. He heard them from Axel Paaske, one of his uncles I think. And I was lucky enough to be part of his family for many years and he was inspired to write these stories down and gave them to me. So you will find these four stories are unique to this collection. Thanks to my former wife, Connie Bloch, for letting me include them in this book.

And thanks to my three children for being who you are, tall and wonderful. I remember every story I told you and it makes me smile and inspires me to tell more.

Alice Fernbank, my fellow storyteller and life partner. You made it possible for me to write this book in a language I have not mastered like you. You brought clarity to each of the stories as the master storyteller you are.

Yours faithfully, Svend

1

DANMARK

Why Danmark is called Danmark.

Once there was a young prince and he had nothing to do. He was the youngest of three brothers. The oldest, Øster, was going to be king of Uppsala when their father died. The second, Nor, was going to be king of the land we now call Norway. But the youngest had not been granted any land to rule.

The prince wanted to make his mark in the world, to be someone, to be recognised. The land to the south was dangerous, it was a belt of forest not yet ruled by men of honour, but by wild beasts and robbers. So the young prince went to his father, King Ypper of Uppsala, and asked for men and ships, which he was granted.

One beautiful spring day with the cliffs shining in the sun they headed south across the Baltic Sea and past a rocky island we know today as Bornholm. Then they sailed towards the north and entered a narrow sea channel between two lands. Both sides of that channel were covered in lush green forests and fields, and all along both coastlines were small clusters of mud huts. The waters were crowded with fishing boats and men hauled nets full of herring ashore. Women filled baskets with fish and carried them to their homes. The prince’s men flung their nets out into the water and within moments the nets were full of silvery herring.

This green land was inviting for the young prince, he knew he could be king here.

They followed the coastline until they came to a deep narrow fjord. They journeyed across the waters of the fjord until their ships arrived at the mouth of a river. On foot they followed the small river upstream until they came to a hill. The prince climbed that hill and looked at the landscape. He saw fresh water bubbling from a spring, and the green hilly landscape ready to cultivate and create fields for the future gathering of huts. The small lakes were filled with fish and the fjord wasn’t far away with lots of herring. Green forests were filled with game.

The prince knew he could rule here. He had his men build a king’s hall, and so he became the first king of Lejre.

One day two men dressed as soldiers asked for permission to speak to the King of Lejre. The men wore armour and had a spear in one hand and a shield in the other. Still, it was clear to the soldiers from the north that these two men were no soldiers, they were farmers dressed in warrior clothes. They were told to leave their weapons and armour outside the king’s hall and when they entered the great hall the new king said hello to the two peasants.

‘We are told that you are a mighty warrior king,’ said the tallest of the two men. ‘We think you are the only one to help us. The Saxons in the south are gathering a great army and if we should fight them alone, it will be the end of an independent Jutland, it will just be a province in the mighty Saxon empire.’

‘Is there anything you have done to prevent the Saxons from coming into your land?’ said the king.

‘We have built a wall,’ said the tall man. ‘We call it Kovirke. It stretches from the west and nearly all the way over to the eastern coastline. Kovirke is on the border between Jutland in the north and the Saxons in the south, but we are not sure if it is strong enough to hold back the Saxon army.’

‘What can you offer in return if I help you?’ said the king.

‘We can’t offer much,’ said the tall man. ‘We are mostly farmers and fishermen and our little army is not going to be any match for the Saxons and the Saxon emperor Augustus will then rule over Jutland. If we lose he will come after you.’

‘Good,’ said the king. ‘We will sail out towards the south of Jutland tomorrow. And you will join us and show us the way.’

Dan gathered his warriors who were happy to have something real to do instead of farming, and followed the two men to Kovirke in the southern part of Jutland. When Dan and his warriors joined the battle, the Jutes advanced against the emperor of the Saxons. The Saxons were crushed in the battle with many men lost, so many that Jutland did not have to fear another invasion from the south for many years.

After the war, the men of Jutland held a ting. They invited the men of the Island Funen to attend and told them of the hero king who had defended their country. The decision was unanimous; they all wanted the King of Lejre to be crowned King of Jutland and Funen too.

So the new King of Lejre had made his mark. He was now king over a kingdom that stretched from Skagen (Scaw) in the north to Kovirke in the south and from the long coastline of Vesterhavet (North Sea) in the west to the shore of the Baltic Sea in Skåne (Scania) to the east.

When the new king was crowned, he stood on the magic stone.

The men all cheered and called out in celebration of the new king: ‘Hail, King Dan! Hail, King Dan!’

King Dan said to the men gathered from around his kingdom, ‘This land is fair and fertile, the waters are filled with fish and the people are strong men and women working hard. Yet, it has one flaw – it lacks a name.’

They answered him, ‘You are Dan, and therefore the land shall be called Danmark.’

The Danish word ‘mark’ means ‘field’ – ‘Danmark’ is ‘Dan’s Field’.

2

KING SKJOLD

If you spotted a Viking ship it meant trouble.

It was early morning. The fishermen were getting ready to sail out into the middle of the narrow fjord where their nets would be filled with herring and eels. The farmers came out of their small mud huts to look after their livestock or go to the fields. It was late spring and the blackbirds were busy telling everyone who wanted to listen that another lovely day had begun. Then in a split second everyone froze as a loud cry from the north end of the fjord called ‘Vikings!’ and fear shot into the hearts of every single human being all the way down and up Roskilde Fjord. Time stood still and even the blackbirds understood that something bad was going to happen and stopped their singing.

It was a slow-moving Viking ship that had been spotted on its way into the fjord and now farmers and fishermen on both sides of the fjord rushed to the fire stands and started the warning fires. The ship was a typical Viking warrior ship with a dragon in front and a square sail on its mast. On both sides were round shields covered with brown calfskin, showing that the men aboard that ship were ready to fight anyone coming near it.

There was nearly no wind and the ship sailed slowly towards the southern end of the fjord. No oarsmen were to be seen on the ship and the silence was unbearable for the farmers and fishermen waiting for the wild horde of Vikings to jump down from the ship and kill, rape and loot.

The women and children and the old folks were trying to run away from the village as fast as they could, which wasn’t fast at all. The last woman to flee was the potter’s wife and she turned around to get a final glimpse of her husband.

It was a miserable sight to see the men with their rakes and wooden clubs, a few spears and one or two shields waiting for the roaring Vikings. The men held their makeshift weapons, getting ready to at least hold back the intruders long enough for the villagers to escape. The potter’s wife caught the eyes of her beloved husband, who smiled bravely at her. He saw their newborn tied to her back and he felt that overwhelming love for his family that always made him breathless. Then they all heard the sound of the ship landing on the banks of sand. The men bowed their heads ready to die. But nothing happened.

The potter’s wife, instead of running away to safety, slowly approached the fjord. Then they all heard it. A baby crying. First the potter thought it was the baby on his wife’s back, but when he looked at her, she shook her head and pointed at the ship. He raised himself from his hiding place in the dunes and looked bewildered as he saw his wife walking out into the water towards the side of the ship.

The potter’s wife climbed aboard and in the middle of the ship she found a baby lying on a shield covered with sheepskin. She took the baby, unleashed her blouse and fed it right there. When the potter climbed aboard he saw his wife with their baby happily sleeping on her back and a stranger baby boy suckling at her breast as though he had never done anything else in his life. She pointed at the shield in the middle of the ship where she had found the boy. Around it was so much gold and silver that it made the potter speechless.

‘You had better tell the others,’ she said.

The potter stood up and shouted, ‘There are no Vikings here. There’s just a baby boy!’

All the men laughed with relief. The women and the old folks and the children came out from their hiding places and the celebration lasted all day and long into the night.

It was decided that the potter and his wife should raise the boy. And so they did. He was the strongest, cleverest and most gentle boy you could imagine. He loved his family, even though he knew they were not his blood. They called him Skjold, the Danish word for shield.

One day when he was only fifteen, a bear attacked him. Skjold killed the bear with his bare hands.

The rumour of a strong young man, born as a prince with gold and silver to prove it, spread and came to Lejre, where there was a need for a king. Skjold left the village by the fjord, said goodbye to his family and became King Skjold in Lejre, who ruled all the land. When people spoke of King Skjold they said that he was the son of Odin and was destined to rule the Danes. King Skjold did rule wisely for many years and with the Saxon Queen Alvilda he had many sons and daughters. The children of Skjold and Alvilda were called Skjoldunger and from them lots of stories came of bravery, wisdom and kindness.

And if women were part of a Viking army they called them Skjoldmøer in respect to the old King Skjold.

When King Skjold died, they brought him back to the ship he came on. They gave him a shield covered with sheepskin to rest his head upon and gave him silver and gold for his journey. Then they launched the Viking ship out into Roskilde Fjord like the ship had entered the fjord many years before.

3

TORA AND RAGNAR

‘Lind’ means soft or bendy; ‘orm’ is the Swedish word for a snake.

Where the River Göta met the sea the land was called Götaland. There three kingdoms met: Denmark from the south, Norway from the north and Sweden from the east.

In that land a jarl (a Scandinavian word for a king of a small piece of land) had a daughter named Tora whom he loved more than anything in the world. He had built a house for her and every day he brought her a gift. One day he gave her a tiny lindorm: a slim, green, snake lying sweetly in a little box. The snake was lying on gold coins and as it grew so did the number of gold coins beneath it.

Time passed and Tora grew into a beautiful young woman and was ready to be wedded to a suitable man. But as she had grown, so had the slithering, green snake and it was too big to live indoors so it lay outside and wrapped itself around the entire house. It was as thick as a barrel of mead and under it lay a treasure of gold coins. But the snake who had once been her beloved pet had now become her fierce protector and would not allow any man to come close.

One day a young man from the village tried. He approached the house determined to rescue the beautiful Tora. He raised his sword and charged at the snake, which lifted its head and spat poisonous venom over the young man’s body. He died instantly. Tora watched from inside feeling angry and helpless.

No man from the region ever tried to rescue Tora after that.

Tora’s father was desperate to free her. He announced to all three kingdoms that any man brave enough to overcome the lindorm and release his daughter would be granted the lovely Tora and all the gold lying beneath the snake.

Across the sea in Denmark there was a young Viking warrior called Ragnar who was preparing a voyage to Greenland with his men, when he heard about the beautiful young woman who was imprisoned by a lindorm. He and his men boarded their ship in high spirits equipped with food, weapons and furlined clothing for the cold winds of the north.

Before leaving Denmark, Ragnar had taken his hooded furlined coat and trousers and turned them inside out. He had then dipped the coat and trousers in tar and hidden them from his men.

On their way to Greenland they sailed along the west coast of Scandia and Halland. As they passed Götaland, Ragnar told his men to stop and get supplies on land. They anchored in a bay not far from Tora’s house.

Next morning before his men woke up, Ragnar put on his tar-covered trousers and coat. On the beach he rolled in the sand, making sure that it stuck to the tar on his clothes to create a protective coating from the snake’s venomous spit. He then took his spear and loosened its head from the shaft, so it would be easy to pull the shaft away.

Silently he crept towards the back entrance of Tora’s house. The snake was busy watching for intruders at the front door, so it didn’t discover Ragnar before he shouted, ‘I am here, you monster!’ and stabbed the middle of the lindorm with his spear several times, knowing that it would bounce back off its thick scaly skin. Tora, hearing the deep voice of Ragnar from the back of the house, ran to her kitchen window and couldn’t believe what she saw, a strange-looking creature covered in sand tormenting the snake with his spear.

The lindorm swiftly slithered round the house to the back door and spat its venom over Ragnar, expecting to see him shrivel and die. But Ragnar’s hairy breeches and his coat covered in tar and sand protected him from the poison. He aimed his spear and threw it swiftly into the soft skin below the snake’s throat, piercing its heart. The lindorm gave a final hiss and its head crashed to the ground.

Tora felt the whole house shaking as the snake collapsed.

Ragnar then pulled the shaft from the head of the spear and looked up. There she was, looking at him from the kitchen window. She was stunningly beautiful. He turned and walked down the hill towards his ship and his men.

When his men saw him coming, all covered in tar and sand they laughed. They gathered on the beach and Ragnar told them about his adventure.

‘What happened to the gold?’ said one.

‘And the girl, where is she?’ said another.

‘They will come, I am sure. We just have to wait here,’ said Ragnar.

Tora stepped out from her house to see that the snake was indeed dead. Her father came running up the hill to the house.

‘The lindorm is dead,’ Tora said.

She found the head of Ragnar’s spear in the heart of the snake and pulled it out.

‘What happened?’ her father said, ‘Who killed the lindorm?’

‘I don’t know,’ Tora said, ‘it was like a black bear covered in sand and when it saw me, it ran down the hill.’

‘We must find out who did this and give him his reward,’ said the Jarl. ‘Whoever’s shaft fits this spearhead is the one.’

The next day young men from across the region came to the jarl’s hall carrying spear shafts in the hope that theirs would fit the head of the spear, but none did. Outside the hall Tora stood waiting for her father to call her in when they had found the one who had killed the lindorm. As she stood there she noticed the Viking ship lying out in the bay. The Vikings had not been invited and as Tora thought about it, her saviour could easily have been one of them, something that her father wouldn’t approve of.

By and by her father came out of the hall shaking his head. None of the men’s shafts fitted the head.

‘It could be one of the Vikings,’ Tora said, ‘you know they have been lying in the bay for three days now.’

Her father looked bewildered at his daughter. She didn’t look frightened by the prospect that it could be a Viking that had saved her and therefore deserved to be married to her.

Reluctantly he walked down towards the Viking ship and Tora followed her father down to the shore.

The jarl called out to the men on the ship, holding up the head of the spear, ‘Good day, brave men, is there anyone on your ship that has a spear that could fit to this head?’

The men gathered together on the ship and looked. One of them said that it could be Ragnar’s. ‘Oh, yes,’ said another in a casual manner like it didn’t mean anything, ‘we can ask him.’

And the Vikings laughed out loud as if something was really funny that the jarl couldn’t see. He was about to ask what was so funny, when the men stepped aside to let Ragnar come forward. Tora gasped. She had expected a black hairy monster, but what she saw made her heart quicken. Ragnar was a handsome, strong young warrior king and when he spoke it was a real man speaking.

‘What do you want?’ he said in this deep dark voice that Tora felt she already knew so well even though she had just heard it twice by now.

‘I want to find the man who killed the lindorm,’ said the jarl, ‘so I can give him his gold.’

‘There was another prize,’ said Ragnar, ‘can I see her?’