Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Carcanet Poetry

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

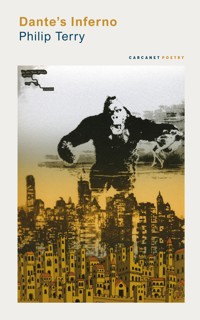

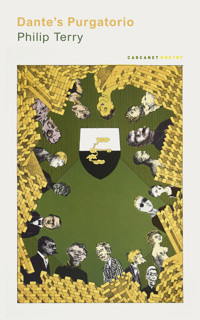

A sequel to Philip Terry's Dante's Inferno (2014), where Dante relocates to the University of Essex, here the action shifts from Dante's Island of Purgatory to Mersea Island, in Essex still, where the poet and his guide Ted Berrigan climb a mountain made out of Flexible Rock Substitute (FRS). Dante's artists are replaced with contemporary artists and artists-in-residence on the Essex Alp, including Grayson Perry, Rachel Whiteread and Damien Hirst. Hirst, an example of pride, is encountered not carrying a rock on his back, as in Dante, but carrying a washing-machine, a Siemens Avantgarde, which runs through its spin cycle as he carries it. Other characters encountered include Christopher Marlowe, Boris Johnson, Lady Diana, Jean Paul Getty, Hilary Clinton, Allen Ginsberg, Samuel Beckett, Martin McGuinness, Ciaran Carson and Anoushka S hankar. On the final terrace, the poet, accompanied by Berrigan and poet Tim Atkins, passes through a wall of flames to reach Dante's Paradise, here modelled on the Eden Project, where the poet meets his Beatrice, Marina Warner. The poem comes to a climax with an interview with Marina Warner in the LRB Tent, followed by a gig from the Pogues, for which Shane MacGowan has been brought up from Hell on an Arts Council 'Exceptional Talent' scheme.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 254

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Dante’s Purgatorio

Philip Terry

CARCANET POETRY

Contents

Canto I

For better waters, now, the little smack

Of my inwit hoists its sail

Leaving behind the bottomlesss gulf,

Whose misery gouged deep its keel.

I will sing now of that strange island

Where the good dead are made better

And beaten into pure form,

Becoming fit to build on Earth a better place.

Oh Oulipo, who set free my voice,

Here let dead poetry live again,

And let Calliope sing along with that sweet

Contralto, whose strain shut the magpies up for good.

Like a photoshopped image of dawn

The radiant light of the sunshine coast

Burst from the horizon,

Blinding my dimmed sight with its refulgence,

So that I had to narrow the slits of my eyes

Which had grown accustomed to Hell’s dark.

Like distant laughter,

The planet Beckett described in Ill Seen Ill Said

Rose above the fishing boats anchored offshore.

I turned to the right, fixing my peepers on the

Other pole,

where I saw four wind turbines gleaming:10

The sky seemed to welcome their giant forms

As their blades began to turn

Bringing clean energy across the waters.

When I had finished gawping, I checked the football

On my phone – the ball was passed back in front of goal,

To where Wayne should have been, but he was gone.

I saw nearby an old man, standing alone,

his hair was all white,

his complexion bright,

And as I gazed into his eyes I recognised

Once more a man I had met on Earth,

The tenant of Bottengoms, author of Akenfield.

The breeze that swept across the shore

lofted his hair

Like a rock star’s in front of a wind-machine.

‘Who are you, travellers, who have escaped

The eternal prison inside the Knowledge Gateway?’

He said, eyeing us haughtily.

‘How did you get here, against the blind current,

Or have the bus routes changed,

Or the laws of the VC been broken?

Is there a new edict in Senate such that

The damned, on day release, may wander into my

Caravan Park unchecked, from the Infernal Campus?’11

Berrigan, my guide, seized me from behind,

And with a word in my ear and a nudge with his knee

Made me bend down and pay my respects.

Then he replied: ‘I didn’t come here of my

Own volition. A lady from London, lauded by

Knopfler – you may know the song, “Lady Writer” –

Asked me to help this man out of a fix.

But since you’re asking what the Hell

We’re doing here, let me put you straight.

This man has yet to pop his clogs,

But, through his misfortune, was so damn close to death

That there was barely time to turn things round.

As I’ve said, I was sent

To rescue him, and the only way was down,

The only way was Essex.

Already I have shown him all the damned souls

In the Infernal Campus, now I want him to see the good dead

Who come to rehab, here on the Essex coast.

How we got here?

How long have you got, old man? Put it this way –

When we set out on our journey through Hell,

Three days since, nobody had heard of Covid-19,

And now I’ve got a signal on my phone it’s all I read about.

From the AHRC comes the funding that brings him here,

So don’t think about turning us back,

Make us welcome, like refugees fleeing a warzone,

We’ve seen some shit, so give us a break man.12

Senate’s edicts have no hold on us;

For this man still lives, and I am no lackey of Landman.

I’m from the same zone as your friend Imogen Holst –

Along with another bunch of artists –

She still talks fondly of you, so for her sake,

If for no other reason,

Let us travel through your seven zones.

I’ll give her a big hug for you

If you don’t grudge being mentioned in that place.’

‘Three days, you say,’ he mumbled,

‘I think you’ve been in Hell longer than you think,

But time can do funny things down there.’

Then he pulled on a face mask and approached us gingerly,

Pointing a temperature gun at our chests.

‘Looks like your Covid-free, but I have to be sure,’

He said. ‘Like New Zealand, this island is

Virus-free, but I mean to keep it that way.

Any arrivals from the mainland have to self-isolate

Before making the trip over the water,

And we check them once more on disembarkation,

We don’t want to take any unnecessary risks.’

Relaxing a little, he went on: ‘When I was working

For dear Ben at the Aldeburgh Festival in its infancy

Imo was so pleasing to my eyes

That everything she asked of me I did.

Now that she dwells beyond the evil river

She can no longer move me, such things are governed13

By an immutable law buried in the university charter.

But if this lady from London, winner of the Holberg Prize,

Moves and commands you, just ask in her name.

Go then, and see that you hitch up this man’s

Trousers – a smooth rush should do it – and wipe off

All this filth

That has so clouded his face

He looks like a paramilitary:

To climb this mountain you’ll need to look smart.

All around the border of this little island,

There where the waves erode the shore,

Are rushes growing out of soft clay.

No other plants that put forth leaf or lignin

Are able to thrive here, for they cannot

Yield to the constant buffeting of the North Sea.

Once you’re done, don’t return by this way.

The sun, which just now is rising,

Will show you the best route to tackle this mountain.’

With that, he disappeared; and I stood up,

Without a word, dusted myself down,

And rejoined Berrigan who was lighting a smoke.

He took a draw, then said: ‘Let’s go dude, we must turn back,

The beach here slopes down to the shore,

Beyond the remains of the old Block House.’

The dawn crackled,

dissolving the morning mist,

Which rose then vanished in the air.14

We plodded on across the lonely beach,

As people looking for some precious object they have lost –

Like a couple I once saw in Snape who lost their wedding ring –

Until we reached a shady part where the

Dew resting on the banks of grass still lingered.

Here Berrigan grunted, and kneeling down in the wetness

He held out both his outstretched palms

And rubbed them all over the grass:

When I saw what he was about

I stepped over and offered him my cheeks

Which were stained with tears, and there,

Applying his hands like a masseur

He once more brought to light my native

Complexion which Hell had hidden.

We came then onto the deserted shore

Which never saw any sail upon its waters

That belonged to the land of the living.

Then Berrigan bent down and plucked

A stiff rush, wincing as it cut into his poet’s hands,

And tied it round my middle like a belt.

And when he plucked this humble plant,

Miraculously, it renewed itself before my eyes,

Like some genetically modified crop that can

Copy itself once harvested,

There, in the very place from where he had taken it.

Canto II

‘Now,’ said Berrigan,

‘The sunrise in these parts, they say,

Is awesome – let’s check it out!’

As he spoke he took out his gear

And hunkered down on the beach

To skin up.

‘Look at those colours, dude,’ he drawled,

Handing me the smoke,

And as I took a draw

I swear the dawn changed colour

Now yellow, now pink, now deep orange,

As it filled the horizon.

We were still sitting there by the water’s new day,

Like stoners, absorbed in the now,

Not even thinking what our next steps might be,

When suddenly I saw, low from the north

(Like the red glow of Bradwell that burns at dawn

Through the dense haze that hovers on the sea)

A light – so may I see it again! –

A bright light, travelling like lightning

Over the sea, far faster than any jet ski.

I turned to question Berrigan, my guide,

But he just sat there cross-legged, without moving,

Like some Buddhist monk, toying with his beard,16

Then when I looked back I saw the light

Both brighter and bigger grown.

Then, on each side of it,

I began to make out some white thing,

And beneath it too, little by little,

Another whiteness became visible.

Berrigan sat there without uttering a word,

Until the moment when the first white things

Became clearly visible – they were wings! –

And beneath them hung two floats, the

Landing gear of what looked like an amphibious plane,

And when he recognised the craft, Berrigan cried:

‘Now bend your knees! That plane’s the Angel di

Dio, and if I’m not mistaken the pilot’s Amy Johnson,

The first woman to fly solo from London to Australia.

See how close to the water she flies! How

Tightly she turns! Those goggles, that scarf,

That flying helmet, I’d recognise them anywhere!’

Then as more and more towards us came

The bird divine, brighter yet it appeared,

With the brightening beam of the rising sun behind,

And I had to look down

not to be blinded

by the glare.17

Johnson brought the craft down on the water,

So gently slicing through the waves

That there was no backwash at all.

I could now see the pilot clearly in the cockpit,

And all the faces peering out,

There must have been at least a hundred

Packed in there, as if they’d been taking a lesson

From Ryanair,

and as they touched down

They sang together with a single voice:

‘We are the champions, my frie-end!’

With all that follows those words on the album sleeve.

Then she pulled a lever above her head

And the cabin doors slid open, no, they became slides,

The passengers sliding out into rubber dinghies,

Which inflated at a touch, propelling them to the strand.

Moments later, and she was gone,

Her cargo stranded on the shore.

Men in white bodysuits and goggles,

Holding infrared thermometers, met them,

To check their temperatures as they passed.

The throng left there seemed not to understand

What place it was, or what was happening, but stood

And stared about like refugees arriving in a new land.

The sun, which with the infra-red in each ray,

Had chased the vapour trails from the height of Heaven,

On every hand was shooting forth the day,18

When one of those new souls looked up to where

Berrigan and I stood on the strand, saying to us:

‘If you know it, show us the road that leads

Off the beach and takes us up the Essex Alp.’

To which Berrigan replied with a drawl:

‘If you think that we’re from around these parts,

Think again, stranger, we are aliens like yourself.

We arrived but now, a little before you,

By a way that was so rough and hard

The climb that lies ahead will seem like child’s play.’

The creatures, who must have clocked from my breathing

That I was still alive, stood gawping in amazement, and

As to some messenger in an antique play, who bears

The olive, people draw near to hear the news,

So on my face those pilgrims fixed their gaze,

Those fortunate ones, momentarily forgetting why

They had come to this strange island.

As they stood there staring I wondered what

Had brought them to their ends – some, by the look

Of them, had died from old age, but among their numbers

Were many who had died young,

Their lives cut short by leukaemia, cancer,

Cirrhosis of the liver, a crash on the roads, Covid-19.

One of them I saw breaking the ranks,

And he stepped forward to embrace me

With such great warmth

That he moved me to do the like.19

Oh shades empty save in outward show!

Three times behind its form I clasped my hands,

Three times they returned to my sides through empty air.

With wonder, I believe, I must have changed colour,

Because the shade smiled ironically, then drew back,

Unable, at last, to contain its laughter.

Then he told me not to waste my time, he was

A shade, and by his voice I knew who he was,

And begged him to stop a while to talk to me.

‘Just as I had time for you when I was in my mortal body,

At least when that body wasn’t getting some nookie,

So I have time for you now, friend. But what brings you

To this place? Spill the beans.’ ‘Aaron, my old shipmate,

I make this journey, how shall I put it, to find myself,

Accompanied by this ancient poet, but what brings you

Here, at this moment?’ ‘For some time now I’ve been

Shored up in one of the pubs in Brightlingsea, The Railway

Tavern – maybe you know it? – playing lead guitar with

The Vibrators, who’re back on the road, yet for three weeks now,

Just as Merkel took in refugees in 2016, they’ve been letting

Anyone cross the water who was up for the trip,

And so it was that I took my turn to wait

On the foreshore, self-isolating, there where the waters

Of the Colne grow salt, and arrived just now with our pilot.

For that same shore now she has set her sat nav,

Because crowds gather there all day long,

All who do not sink down to the Infernal Campus.’20

And I: ‘If some new law governing this place,

Or your disembodied form, does not prevent you

Playing that guitar you carry, as you used to,

Please, take that instrument out of its case,

And give us a tune, if only for old time’s sake!’

Then he took out his guitar, as we sat on the strand,

And started to sing ‘Flagmen’,

With a voice that was a little rusty,

But on guitar he was still note perfect:

‘Wet grass, and a co-old night,

Flat shadows run in front of blue lights,

Flags broke and splintered,

Saw voices in the dark –

They became a fighting uuunit…’

We were all fixed on his performance,

Getting into the groove,

When, what do you know, Ronald Blythe showed up,

To put a stop to the party. ‘What’s going on?’ he said,

‘This is no time for a beach party. You won’t catch

Coronavirus on this island – like Guernsey, like New Zealand,

We’re Covid-free, but that’s no reason

To forget where you are and why you’ve come here.

There’s work to do! Come, you need to get yourselves

Off the beach, and ready yourselves for the climb.’21

As ravers breaking lockdown, pumping the air with crazed fists

In some Devon barn, turn pale and flee

When the police raid the joint, running to their vehicles,

So, at that moment, did those newly arrived souls

Turn white

and pick themselves up off the sand

Moving

one by one

towards the sea wall bounding the island.

Nor was our parting less quick.

Canto III

Those frightened souls now scattered across the shore,

Legging it over the sand towards the Essex Peak

Where the good dead learn to climb,

While I, as we ran, not knowing what to do,

Stuck close to Berrigan, my guide,

For who else could show me the way?

He looked, when at last we stopped, completely out of puff,

Standing, bent, with his hands on his knees,

Red-faced, wheezing.

Then, when he stood up, lighting a smoke,

Now free of that haste which mars our dignity,

My mind, which had been caught up in the adrenaline rush,

Now relaxed, and I looked around at ease. Towering above

The shore, like nothing I had seen before, like nothing,

Certainly, I had seen in Essex, rose a great craggy peak,

While blazing red with its light behind us, the sun

Outlined my human shape on the sand

In front of me, as my body obstructed its rays,

And seeing only before me the earth darkened,

I turned around in panic,

Fearing I had been abandoned.

‘Loosen up,’ said Berrigan, my guide,

‘I’m not about to walk out on you now,

Not after all we’ve been through.23

It is still night time over Calverton National Cemetery

Where my body, that once cast a shadow, is buried;

From Greenwich Village to Long Island it was moved.

If now I cast no shadow before me,

Don’t look so amazed. It’s no stranger than

The fact the sun’s rays don’t block each other out.

Yet bodies such as mine are still sensitive

To pain and cold and heat –

And we still get out of breath, as you see.

Get used to it – there’s another world,

A world of spirits, running parallel

To the real world.

It’s the same in the infernal region we left,

For in the material world the real

University still carries on its business

As Vice-Chancellors come and go.

Materialists don’t accept this,

That’s why they live without hope, in desire –

You met some of them down below,

Richard Bartle, Roy Trubshaw, and

The astronaut Rodolfo Vela,

And there are many others,

Not just those with Essex connections

That I showed you.24

But you met them at the start of our

Journey, I may have glossed over

Some of this, just to keep things simple.’

Ted bent his head for a moment, staring at the earth,

He looked pissed off, but I don’t know what was eating him –

Maybe that I was a slow learner? Maybe something else?

By now we had come to the shore’s limit

And there we found a sandy cliff so steep and slippery

The nimblest legs would not have served you there.

The craggiest, the cruellest precipice,

On the slopes of Ben Nevis would seem,

Compared to this, inviting stairs to climb.

‘How are we to know,’ said Berrigan my guide,

‘Just where this cliff face might let us climb,

So that those without crampons might ascend?’

While he stood there, head bent,

Wondering how we should best proceed,

And I was gazing up at this wall of sand –

Along the base of the cliff, to my left,

A crowd of shades was inching towards us,

Who seemed barely to advance, they came so slowly,

Like victims of Long Covid. ‘Master,’ I said, ‘take a

Look over there! These climbers advancing over the

Strand might show us the way if you think we’re lost!’25

He looked up, his face now free from doubt,

And said: ‘Let’s go and meet them, they move so slowly,

Buck up now, they might just have a map.’

After we’d trudged the sand for a good five minutes,

The crowd were still as far off

As Peter Shilton might kick a ball upfield,

When, all of a sudden, they pressed close to the

Sandy cliff, standing still, huddled together,

As one halts who sees some peril ahead.

They looked like climbers, for the most part, kitted out

With all the gear – ropes, helmets, and bright blue boulder mats –

Though some wore dark cloaks, like priests or wizards.

‘Hey there, you! You the good dead, who are

Already chosen,’ Berrigan called, ‘by that same peace

Which I believe you are all in search of,

Tell us where this cliff slopes, so that

We can get a foothold on it – we are climbers

Like you, and wish to go up the mountain.’

As sheep come forth from the fold, in ones,

In twos, in threes, and the others hold back,

Casting their eyes and noses about,

And what the first one does, the others copy,

Huddling up to her if she stands still,

Silly and quiet and knowing not why,26

So then we witnessed the leader of that flock

Take a step in our direction,

Modest in look, head held high.

Yet when those in the fore saw the light

Broken on the ground to my right side

So that the shadow fell from me dancing over the cliff,

They halted and drew back, and

All the others that came behind did likewise,

Not knowing why.

‘Before you ask let me tell you that this

Is a human body that you see

By which the sun’s light on the sand is cleft.

Don’t stand there gawping – it is not

Without help from a high place

That this soul looks to climb this wall.’

So said Berrigan, my guide, and the climbers replied:

‘Come, this way, where there’s a path up the cliff,’

Gesturing to us with their hands.

Then one of them began with a cavernous voice: ‘Whoe’re thou

Art who journey’st this way, thy visage turn;

Think if my face thou hast seen in the history books?’

Startled, I turned towards him, looking him up and down.

He wore a grey cloak and a blue cap, like some

Medieval pilgrim, and he had a gentle face,27

Except there was a gash under one of his eyes.

I had to confess, embarrassed, I didn’t have a clue who

He was, at which point he turned to me:

‘Now behold!’ he said, pulling back his cloak

To reveal great cuts where his arms began,

‘I am John Ball, of Colchester, Bishop of the People,

Who helped the peasants rise up against their oppressors.

The stories told about me are many, but when you have returned

To the Earth, tell them what you heard from me,

If other tales are still told. When by five mortal blows

My frame fell, my body was dismembered,

The parts dispersed to four corners of England –

Coventry, Chester, York and Canterbury –

So that none may make vigil at my grave.

When these blows my frame had shattered,

I betook myself weeping to Him who of free will

Forgives. My sins were many, if less than my enemies claim,

But so wide arms hath goodness infinite,

That they receive all who turn to them.

Had this text divine been of Sudbury better scann’d,

Who excommunicated me for free preaching,

My body would yet lie in one place, ’neath hallow’d ground.

Yet by such curses are we not so destroyed,

But that the eternal love may turn, while hope28

Retains her verdant blossom. True it is, withal,

That such a one as in contumacy dies

Against holy Church, though he repent,

Must wander thirtyfold for all the time

In his presumption past; if such decree be

Not by prayers of good men shorter made.

Things cannot go aright in England and ne’er will

Until goods are held in common and there are no

More villeins and gentlefolk but we all are the same.

Look therefore if thou canst advance my bliss,

Revealing to your age how thou beheldst me,

And the terms laid on me of that interdict,

For here from those below much profit comes.’

Canto IV

When you’re completely engrossed in a movie

On Netflix, or sitting on the edge of your seat

Watching a football game,

Or if you’re involved in a road accident, say,

Your car spinning out of control into a ditch,

Or straight into a tree, you lose all sense of time,

So caught up in the moment are you

That time itself seems to expand

As a gas expands to fill all the available space –

Something which never happens

when you’re multitasking

And which is alien to the business mindset.

I was now experiencing this for myself

As I listened, marvelling, to the words of John Ball –

For the sun had risen a good 45° into the sky

And I had not even clocked it –

When, at a certain point along the way, these climbers

Cried out in a single voice: ‘Here’s what you’re looking for!’

A bigger opening is often closed up by a

Bricklayer, while his apprentice stops for a fag

Break, than that narrow gap we now climbed through,

Berrigan, my guide, first, I after him,

Followed close by the climbers

with a weary tread.30

Maum Turk Mountains you can scale, edge up

Mount Gable, climb to Dunluce Castle, ascend Errigal.

Feet will do there, but here you must scramble on hands

And knees. Squeezed between crumbling walls of sand,

We struggled upwards through that eroding cliff wall,

Clinging to roots when our foothold gave way.

Behind us the climbers took out their picks,

Using these to haul themselves upwards,

Securing footholds with crampons, throwing back ropes.

Once we emerged on the upper edge of this

Sandy cliff, once more on open ground,

‘Berrigan,’ I said, ‘where do we go now?’

And he replied: ‘Do not lose your nerve now, we

Must keep straight on if we wish to climb the mountain,

But first we must stop at the Visitors’ Centre,

Where we can get a hold of a pass and some maps,

Until we find a more experienced guide.’

The mountain, from here, rose up higher than I could see,

Disappearing into the cloud layer, and as I looked I stumbled

Back, overcome by vertigo. When I had pulled myself together,

I said to Berrigan, voicing what was bugging me:

‘Tell me, I’m confused, I thought we were on Mersea Island,

But this mountain is like something you’d find in the Alps,

Or the Pyrenees, or in Northern Spain – Essex is flat!’31

‘Listen,’ said Berrigan, ‘you’re forgetting what I said before,

About the spirit world running parallel to the real world: this

Is not the real Mersea, where Jos Williams moors his boat,

And where he teaches courses on astronavigation

To the young sailors of West Mersea, so that they can,

Without the aid of GPS, travel safely across the ocean,

But a parallel Mersea, in a parallel Essex. In this Essex

There are mountains, some of the highest in the world,

But who knows, in some divergent future there may well be

Mountains in the real Essex, whether thrown up by the

Wivenhoe fault, or by the intervention of climate artists,

For much of this landscape is under threat from the sea,

And mountains not only form a barrier against erosion,

But aid habitat development, and precipitation, as well as

Carbon balancing, coz of the flora and fauna they support.

But don’t be so amazed – this journey will require

A willing suspension of disbelief, as Coleridge says,

Which he defines as poetic faith. When you get

Back, you should check out his Biographia Literaria

If you don’t know it – it’s got some real pearls.

Now, let’s make tracks for the Visitors’ Centre.’

Already, ahead of us, we could see some of the climbers

Making their way across the grass, some peeling

Off towards the Caravan Park, others purchasing tickets

For Magic Puffin, or to make their way up the mountain.

When we’d caught up, we went into the shop to ask for help.

They gave us a Guidebook and a plan, marking32

A series of tracks, from Easy to Difficult,

And themed walks: The Route of the Gluttons,

Marked in red, The Way of the Indolent, marked

Blue, The Path of Excessive Love of Earthly Goods,

Marked green, and a number of others I forget.

Berrigan chose the route marked Difficult,

And we were furnished with new boots, a stick each,

And some rope which Berrigan hitched to his waist.

They gave us a little card, as well, with a Puffin logo

On the front, to be stamped as we proceeded,

Making our way up past the way-posts.

I saw Berrigan pulling something out of his breast pocket,

Which he swallowed, then in an instant he was off,

Striding energised towards the mountain.

I felt the strength draining from my legs

As I hurried to keep up. ‘Berrigan,’ I cried,

‘Unless you slow your pace you’re going to lose me –

The biggest peaks I’ve climbed are those outside Sheffield,

Which are nothing to this one.’ ‘Son,’ he said,

‘We need to make a brisk start. Keep climbing, past the blue

Markers, just to there’ – and he pointed to a narrow ledge,

Not far above, that skirted the mountain.

His words were like a goad, and I strained on,

Behind him, on hands and knees and elbows,33

Until I felt the ledge under my feet at last.

Once here, we both sat down for a smoke,

Looking back at all we had climbed.

The shore was now far below us, out at

Sea we could see tankers on the horizon, and below

New streams of climbers arriving at the Visitors’ Centre.

‘That was worth it,’ I said, between puffs,

‘For the view alone – it’s something else.

But tell me, for I can’t keep this pace up for long,

How much more climbing are you planning on doing?

This peak soars higher than my eyes can see.’

‘This mountain,’ he said, stubbing out his cigarette,

‘Is not like other mountains. To begin with,

Sure, it’s hard to climb, but here,

Look what it says in the Guidebook: “Climbing

The Essex Alp offers the visitor a unique

Experience: here, the more you climb,

The easier it gets – that’s a guarantee –

Until the slope feels gentle to the point

That climbing becomes as effortless

As drifting down the Colne in a canoe.

At this point you will have reached

Your journey’s end, and you can enjoy

A welcome rest in our visitor facilities.”’34

Hardly had Berrigan finished reading

When we heard a voice from nearby call: ‘You’ll

Need a fucking rest long before you reach any facilities!’

We turned, shocked, to where the voice had come from,

And to our left we saw a massive rock surrounded