3,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

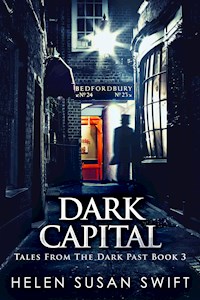

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Abenteuer, Thriller, Horror

- Sprache: Englisch

Edinburgh, 1820s. On one side is the Old Town; ancient, crumbling and full of poverty. On the other is the New Town - elegant, refined and prosperous.

When newly qualified Doctor Martin Elliot arrives, he discovers that the duality goes deeper. There is more darkness in the streets than he could have imagined. Ghosts of the long-dead haunt the houses, and nightmares soon fill Martin’s head.

Only a relic of the past - a dark, carved staff - seems to give Martin respite. But can be balance its power with the burden that comes with it, or will evil overcome his good intentions?

Dark Capital is a standalone novel, and can be enjoyed even if you haven't read other books in the series.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

Dark Capital

Tales From The Dark Past Book 3

Helen Susan Swift

Contents

Prelude

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Epilogue

Historical Note

Next in the Series

About the Author

Copyright (C) 2020 Helen Susan Swift

Layout design and Copyright (C) 2020 by Next Chapter

Published 2020 by Next Chapter

Edited by Terry Hughes

Cover art by Cover Mint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author’s permission.

“The whole city leads a double existence.”

Robert Louis Stevenson

“It is quite lovely – bits of it.”

Oscar Wilde

Prelude

I sit here in the dim candlelight, with the remainder of my life steadily ticking away.

Tick, tock, tick, tock.

As I sit, I ponder. A clock is a very sinister machine as it slowly marks the passage of one’s life, with every tick a second less to live, every trembling movement of the hand informing the watcher that he has used up more of his allotted span.

Tick, tock, tick, tock.

My clock sits in the corner of the room. Tall as a man, it has the maker’s name, Thomas Reidof Edinburgh, scrolled behind the hands, as if in mockery of the buyer, laughing at me for having purchased the object that counts down what remains of my life. I watch it through narrowed eyes, aware of the exact second it will stop, aware of the implications and now aware of the reasons.

Tick, tock, tick, tock.

Shadows flit outside this room, moving around in this cursed house, silent as the ghosts of the long-dead and the recently departed. I know the shadows are gathering for me. I was responsible for some, while others existed many years before my time, although in a different place in this dark city. I must wait, aching my life away, knowing how long I have.

Tick, tock, tick, tock.

There it is again, that sonorous whirr of machinery, that inexorable mechanical hum that does not care about the frail man who sits in the room, fearful of every sound, jumping at every soft scuff of feet in the street outside, every voice raised in drunken debauchery. I am numb to every sensation except fear, and cannot welcome death as a relief, for I know what must come next.

Tick, tock, tick, tock.

The candle is burning low now, pooling a gradually decreasing circle of yellow light across the table. I should start another before I have to sit in the dark with my thoughts and memories. At one time, I had servants to perform such tasks for me. Now I am alone as my candle comes to an end. See? The flame gutters, flicking this way and that in this draughty room. The sounds outside are fading as the city retires to sleep. Only the night-prowlers are out, those half-human denizens of the dark closes, these predatory creatures who thrive on the weaknesses of their fellow beings, who prey on the vacillating, the foolish and the uncontrolled. I pity them, for they are without pity, as was I, God help me.

Tick, tock, tick, tock.

The candle is about gone, the flame little more than a memory, the smell of melted tallow thick in the room. The dying flame is shining red through the dregs of my claret, reflecting from the cut-crystal in a hundred different patterns, throwing a scarlet glow across the document on which I write. It is like spreading blood, that light, a suitable colour for the paper on which I will inscribe an account of what brought me to this pass.

Tick, tock, tick, tock.

I need more light. I cannot see to guide my pen, my old-fashioned, inexpensive goose-wing quill, across the page. I have to put flame to another candle, a dozen candles, although no amount of light can chase away the darkness that crouches at the periphery of this room and in all the rooms of this house. No flame can clear the shadows from my memory, and light will reflect from that hideous white object that grins and rattles at me always from its position opposite my desk. I have brought myself to this state, and only I can atone for my actions.

Tick, tock, tick.

I must have light. I scramble feverishly to apply a flame to all the candles I can find, gather my papers and place them on the desk to my left, fill my inkwell and sharpen the tip of my pen before leaving the penknife at my side. To some, a penknife may be a potential weapon, but no weapon can defend me now. The candlelight grows, fever-bright, expelling all external darkness without easing my torment in the slightest.

Tick, tock, tick.

I begin to write, in the hope that somebody, anybody, will read this and perhaps understand what I have done. Maybe somebody will forgive me. Perhaps.

Tick, tock.

Oh, dear God in heaven help me.

Chapter 1

Edinburgh April 1825

“Your name, sir?” Mrs MacHardy frowned at me from outside the closed door of the house. A big, busty woman, she stood with her arms akimbo, as if daring me to give a name that was not my own.

“Martin Elliot,” I said.

“Are you Irish?” Mrs MacHardy was immediately suspicious. “I want none of your wild Irish ways here, bringing pigs into houses and drinking all night long.”

For some reason, Mrs MacHardy’s words set the gathered crowd screeching with laughter.

“I am as Scottish as you are,” I said, lifting my chin. “From Roxburghshire.”

Mrs MacHardy grunted, do doubt wondering where Roxburghshire might be.

“Elliot, you say.”

“Martin Elliot,” I repeated, adding, “Doctor Martin Elliot,” in the hope of gaining the woman’s respect.

‘Doctor?” The woman ran her jaundiced gaze up and down the length of my body. I felt she was showing her contempt of people who claimed a medical degree yet who could not afford accommodation in a more respectable part of the city. “Are you one of these wild students that kick up a rumpus every night?”

“I am no student,” I hastened to convince her. “I am a fully qualified doctor of medicine.”

“Are you indeed?” Mrs MacHardy was about 50, by my reckoning, with her nose displaying the broken blood vessels of too-frequent imbibing, while the rest of her was sufficiently large for her weight to strain her heart. I gave her 10 years to live, and that was a generous estimate. “Well, Doctor.” She emphasised the word as if my standing left a foul taste in her mouth. “You sound eminently suitable.” Charitable people might have construed Mrs MacHardy’s grimace as a smile. “If you are sure you want the lease.”

“Thank you.” I tried to hide my relief as I gave a small bow for, in truth, finding affordable accommodation in Edinburgh had been troublesome.

I was in the West Bow, that curious, Z-shaped street that angles down from the Lawnmarket to the Grassmarket, beset with ancient, crumbling houses, secret courts and half-hidden passageways, known as closes. It was not the most salubrious of neighbourhoods, but a purse-pinched doctor must seek accommodation wherever he can. The house outside which I stood was in a dirty little private courtyard, with a small close leading to it, affording a little seclusion without spoiling my access. Quite apart from its affordability, it was within easy reach of the High Street, Old Edinburgh’s main thoroughfare.

A group of people had gathered as we spoke, ragged-looking men and women who watched me suspiciously while bare-footed children made a hideous din that echoed around the courtyard. Above me, the ubiquitous tall tenements of Scotland’s capital city rose to a dull, grey sky, with women leaning out of most windows to observe whatever the world offered in the way of entertainment.

Mrs MacHardy remained on the doorstep, studying me with the strangest of expressions on her broad face.

“That man’s going to live there,” one gaunt-faced woman in the crowd screeched, pointing a long-taloned finger at me.

“He doesn’t know.” Another woman, all dolled up and with a painted face, shook her head, so the profusion of ribbons around her neck shivered in a multi-coloured display of tawdriness. “He surely doesn’t know.”

“He’ll find out soon enough,” a third woman said, pulling a threadbare shawl close over her head.

“Don’t be a fool, man!” a gaunt-faced fellow tried to shout above the hubbub of the crowd.

I attempted to ignore the noise as I watched Mrs MacHardy hold the massive, old-fashioned key as if reluctant to hand it over.

“Do you know anything about Edinburgh?” Mrs MacHardy remained in the doorway, inadvertently blocking my entrance.

“No,” I admitted foolishly. “I gained my degree in Glasgow.”

For some reason, my answer seemed to please the woman. “This house is not a bad place.” The old besom seemed inclined to be garrulous now she was convinced I was neither Irish nor a student. “A major of the City Guard used to live here in the old days. A most respectable gentleman.” She patted the door as if to convince me to come to a decision.

“I’ll take it,” I said, for in truth I was desperate for any sort of accommodation so I could set up my practice. “I’ll soon have this house set to rights.”

The old besom grunted in a most unladylike fashion. “Will you be bringing your patients here? I don’t want a lot of sick people spreading their diseases around. I have my reputation to consider.”

I tried to raise a smile. “I will not,” I said. “I will have my practice in quite another part of the city. I don’t wish to mix business with my home life.”

“Three shillings a week.” Mrs MacHardy held out a grimy hand. “One week in advance.”

I paid her, counting out the silver from my slender resources and watched her secret it away in some recess in her voluminous clothing. Even then, I wondered at the low rent for a fairly sizeable residence, but one must be grateful for small mercies. I could feel the tension from the crowd behind me as if they had never seen a man part with money before.

“Here’s the key.” Mrs MacHardy handed over the iron key that looked as if it might open the gates to Edinburgh Castle, let alone a private house in the West Bow.

The metal felt cold and worn as I grasped it.

“I’ll be back next week,” Mrs MacHardy said. And with that, she was gone, leaving me alone outside that dark doorway, with my single case of belongings, my medical bag and my hopes for the future.

“He’s took it!” the garrulous woman shrieked to her companions. “He’s moving in!”

I was not sure if it was amusement or astonishment that caused the uproar in the ever-increasing crowd. Three men began to argue, pushing at each other until one, a medium-sized fellow with a broken nose and a pockmarked face, smashed his fist into the mouth of his nearest neighbour and elbowed the other in the throat.

“Enough of that,” the gaunt-faced fellow said, pulling the fighting men apart.

As the battlers finished the business with growls and vague threats, I fitted the key in the lock and opened the door. I was not here to pacify drunken brawlers but to attend the capital’s sick, be they poor or wealthy, old or young. Leaving the pugilists to sort out their dispute, I stepped inside.

I did not know when anybody had last occupied the house, but whoever the tenant had been, he had left the place in some confusion. The advertisement had claimed the house to be fully furnished, which was accurate, although the furniture lay around the floor in the wildest disorder, and a man might lose himself in the thick dust that lay on top. Augmenting the grime were the cobwebs, great silver-grey constructions that harboured arachnids half the size of my hand. The creatures scuttled away from me, presumably having never seen a human being before. The house was stuffy, if surprisingly dry, with an atmosphere such as I cannot describe, never having experienced the like before.

“Well now,” I said to myself. “You have made your bed here, Doctor Martin Elliot, and now you must lie in it.”

I am not one of these people who likes to sit and wait for events. Instead, I prefer to make them bend to my will, so, removing my coat, I folded it neatly on top of my baggage and set to work. My first job was to throw back the internal shutters and force open the windows, for I believe that fresh air is a wonderful restorative and cleanser. Unfortunately, opening the window allowed in a profusion of foul scents and raucous voices. I quickly learned that there is little fresh air in an Edinburgh close, so densely packed are the people.

I spent the remainder of that day attempting to clean and scrub the house. I was fortunate that there was a brush-maker in the West Bow, so I spent more of my meagre store of money purchasing a variety of brushes and parted with more copper in buying two wooden buckets.

I locked the door most carefully on each occasion I left the house, although none of the gathered crowd of idlers seemed interested in entering.

“You’re wasting your time,” the gaunt-faced man told me.

“I’ll get the house clean,” I told him, sternly.

“No.” His blue bonnet nearly fell off when he shook his head. “I mean you’re wasting your time locking the door. Nobody will go into that house.”

“I’ll make sure of that,” I said.

The man shrugged and said no more, watching me from the corner of narrow eyes.

Naturally, in a house so old, there was no access to water, so I took many trips to the pump, filling up buckets and bringing them inside to remove what seemed to be the dirt of ages. The people watched me, none offering to help, and most drawing back to create a corridor of humanity on my journey between house and pump. Despite the words of the gaunt-faced man, I had feared that leaving the door open would be an invitation for the petty thieves of the area. However, the crowd seemed content only to look inside, with strange comments in a mixture of Highland, Irish and gutter Edinburgh accents.

“You’re a fool man, a fool,” an elderly man told me as he sucked on an empty pipe.

“In what way?” I asked him pleasantly.

“You’re a fool to take on that house.” He pointed the stem of his pipe towards me. “I’m telling you, no good will come of it.”

“Thank you for the warning,” I said, cutting half an inch off a plug of tobacco and passing it to him.

“Aye,” he said, looking at the tobacco as if it was a block of gold. “You may be a fool, but you’re a gentleman.”

The gaunt-faced man was still watching. He gave a single nod, which might have meant approval, and retained his place against the wall, a position that allowed him the best view inside my house. I marked him down as a possible thief.

Given the apparent reluctance of anybody to cross my threshold, I was surprised when one woman had the temerity, or the bad manners, to step inside my door. She stood there like a statue, watching me without lifting a finger to help or hinder. I bade her a cheerful good morning as I passed, to which she responded with a somewhat brighter smile than any of her compatriots.

My visitor was slightly better dressed than most of the crowd, a woman of about 30, with a bold eye and a fine figure. She stood proudly, eyeing everything as if sizing the house up. Allowing her to remain where she was, I continued with my work.

The bed was sound, but the mattress was crawling with vermin, so out it went, along with the bedclothes. Although I thought these articles might tempt a thief, not one person touched them, forcing me to pay a couple of Irish vagrants to dispose of them, I don’t know where. The gaunt-faced man watched everything, pulling on his pipe and with his bonnet low over his forehead.

By the time I finished my cleansing, the house reeked of strong soap, and the crowd of interested spectators had increased. I allowed them to watch, as I studied them, wondering how such a diverse mix of people could squeeze into such a small area. Among the small tradespeople were the expected ladybirds, the hawkers and pimps, the scavengers and petty thieves, an honest woman or two, a thimble-rigger, a clutch of unemployed navigators, and a minister of the cloth.

“What are you doing with these?” the pockmarked brawler asked when I dragged out the final parcel of unwanted material from the house.

“Getting rid of them,” I said, pleasantly.

“I’ll take them off your hands for five shillings.” Pockmarked held out his hand hopefully.

“Take them if you want them,” I said, “but you’ll not get a penny from me.”

Pockmarked dropped his hand and any interest until I tossed him a silver threepence and watched him disappear with my unwanted rags.

“You’ll be the doctor,” the woman within my door said, staring directly at my face.

“That news travelled fast,” I said.

“Oh.” She stepped further into my house and looked around. “We’ve no secrets in the West Bow, Dr Elliot. I’m Ruth Anderson, as you’ll find out.”

“Good morning, Mrs Anderson.” My bow was more in mockery than sincerity, although the woman returned it with a surprisingly elegant curtsey.

“Miss Anderson.”

“Miss Anderson,” I corrected.

Miss Anderson nodded. “You’ve made a change here already,” she said.

“It needed a good clean.”

“The house has lain empty for a while,” Miss Anderson said.

The crowd were peering in as if I was some sort of exhibit at a show although only Miss Anderson had crossed the threshold. Even the pockmarked man balked at the prospect of facing me inside my house, it seemed, yet all seemed surprised when I firmly closed the door on them.

“Why has the house lain empty for a while?” I asked.

“One of the previous residents was not the best of men,” Miss Anderson said.

I nodded. In that area, I was not surprised. “You don’t seem to mind coming inside.”

“Not at all.” Miss Anderson was examining my house. “I’m not from Edinburgh.” She gave a small smile that revealed surprisingly well-cared-for teeth. “I’m not scared of devils or men.”

I thought that was rather a strange statement, but let it pass. “You’re a Highlander, to judge by your accent.”

“Inverness way,” she said at once. “You’ll be needing a woman.”

“What do you mean?” I admit I was startled by her words. Although medical students and young doctors had a reputation as loose-living, women did not habitually proposition themselves.

Miss Anderson walked through the house, examining every room. “You’ll need a woman to clean and cook.”

I smiled with relief. “I’ll think about that later,” I said.

Miss Anderson laughed. “Don’t think too long, doctor. You won’t find many people willing to work in here. Not in this house.”

“Why is that? Surely one unpleasant tenant won’t frighten everybody off.”

Miss Anderson put a finger along the side of her nose and gave a conspiratorial wink. “This house can have a bad effect on people, doctor, and that’s all I am saying.”

With that, Miss Anderson opened the door and stepped past the few who remained of the crowd and walked away with more dignity than I had expected. The pile of bedding and other materials had entirely disappeared.

I closed the door, for I was tired.

Medical students are not the most prosperous of men, so I was used to living a comfortless existence. Resolving to deplete further the contents of my wallet by purchasing bed covers on the following day, I sat on one of the hard chairs, laid my head on the table and slept. It was not difficult after such a busy day.

I do not know what woke me. It was not the occasional drunken roar from outside the house; I was used to such things from my student days. It may have been the strange light that danced at the periphery of my vision the second I opened my eyes. That was some optical illusion, no doubt. Whatever it was, I jerked awake right away and looked around at the unfamiliar surroundings before I recollected where I was.

When I cleaned the room, I had dusted down the long-case clock in the corner, without winding it up, yet I could swear that it was ticking. Scratching a spark, I lit a candle and allowed the flame to grow a little before lifting the brass candlestick and walking to the clock. I knew my ears were deceiving me, yet I had to make sure.

There was no ticking. The clock was silent, with the hands pointing to six minutes past six. On a whim, I moved the hands to midnight. It seemed neater that way, although according to my watch, it was one in the morning. My candle sent long shadows flickering around the room, showing furniture that was years, if not centuries, out of date. Old, heavy, cumbersome pieces that somebody should have condemned to the fireplace generations ago. I resolved to replace them, provided Mrs MacHardy had no objections. I wanted a home with the most fashionable pieces my pocketbook could afford.

I heard the rattle of wheels on cobblestones and shook my head. Who the devil was driving a coach at this time of night? Unable to resist the temptation, I drew back the shutters and peered outside. The courtyard was empty of course, but by craning my neck, I could see over the rooftops to the West Bow. That too was empty. There was nobody, not even a stray drunkard and certainly not a coach, yet I could swear I heard the rumble of iron-shod wheels on the cobbles and the drumbeat of hooves. Many hooves, too, not just four.

Shaking my head, I closed the shutters again, convinced that either my imagination was taking over, or my hearing was at fault. No, I told myself, I had merely been dreaming, a dream caused by exhaustion and the experience of sleeping in an unfamiliar house.

The candlelight cast strange shadows, highlighting areas of the room I had not previously noticed and created shapes from the furniture, so that I imagined a tall man standing beside the clock, a man with a pronounced stoop and a prominent nose. The shadows darkened a small depression above the fireplace and revealed intricate carvings in the wainscotting. By now, I was wide awake and eager to investigate my new house. I knelt by the wainscotting, tracing the pattern with my fingers. At first, I thought the carvings were merely abstract designs, and then I realised they were animals and people, and such beautifully carved animals as I had never seen before. There were cats and rabbits and horses, all in intricate detail, combined with what looked like human figures, men and women in a state of perfect nudity.

Whoever carved these had an accurate knowledge of the human anatomy, I told myself. I wondered if he had been a student of Greek art, or perhaps had an occupation as a figurehead carver or some such.

I followed the carvings to the furthest corner of the room, placed my candle on a small table and allowed the light to play on the workmanship. The design was different here, vertical rather than horizontal, and abstract, yet still felt as if carved by a master, rather than an apprentice. When I touched the carvings, they moved, and I realised the entire corner piece detached.

“What have we here?” I pulled the corner piece away. It was a walking stick, or rather an old-fashioned staff of dark, heavy blackthorn, surmounted by the image of a man’s head. When I held the candle closer, I realised that the head was only an outline without features or form, while the abstract designs covered the entire shaft of the stick. I held the staff closer, finding it curiously warm and, to my nighttime imagination, it seemed to be pulsating as if it were alive. I smiled at the fancy even as I noted that, although the wood was scorched, the carvings were intact. Overall, it was an imposing piece of craftsmanship.

Holding the staff in my right hand, I walked around the room, smiling. I rather liked the feel of that stick. It seemed to enhance my position, somehow, as if it belonged with me. Perhaps it was because of the high quality of its artistry, but I gained a new sense of power.

I shook my head, smiling at the strange fancies that flooded through my mind. Indeed I laughed out loud, telling myself that I had only found a walking stick, and there was no reason for such foolish excitement. Checking my watch, I saw it was now nearer two o’clock than one, and the day had been busy. Removing my clothes, I lay on the bed frame and was asleep in minutes, with the glow from the unlit fire permeating the room and my staff propped against the wall.

Chapter 2

“This is Granton beach,” Charles said.

I looked along the coast. With the picturesque old port of Newhaven to the east and the humped, green island of Cramond to the west, it was an idyllic spot, yet within easy walking distance of Edinburgh. The waves of the Firth of Forth broke gently on the curving shore, with the spring sun kissing the coast of Fife opposite and a two-masted collier brig nosing through a fleet of a score of local fishing boats half a mile offshore.

“I should be working,” I said. “I should be in my surgery, trying to convince sick and wealthy patients to come to me.”

“You need some relaxation.” Charles was quite persuasive when he tried. “Nothing beats a good swim. Come on!”

The temptation was too much. Pushing my financial and professional worries to one side, I succumbed to the lure of the sea. Hiding behind a group of whins, I dropped my staff on to the turf, and we stripped off and ran into the water. Though it was spring, the water was cold enough to elicit a yelp from me.

“Never mind the chill. You’ll get used to it!” Charles was 10 paces ahead of me, laughing as he splashed through the water.

“You Hebrideans should have gills and fins,” I said, as Charles leapt up and dived under the water, to power forward as gracefully as any fish.

I had always fancied myself as a good waterman, for I grew up beside the River Teviot and spent much of my childhood in the various swimming holes there, yet compared to Charles I was a mere tyro. I laboured in his wake, joying in the exercise and the fresh air, so much more healthy than sitting in my surgery.

“To the island!” Charles shouted over his shoulder and headed for Cramond Island, which was much further than I had intended swimming that day. However, no Borderer can resist a challenge, and I followed, splashing furiously in my attempt to catch him. I did not succeed and was gasping like a grampus long before I came to Cramond, where Charles was sitting on a bank of grass above the beach, grinning at me.

“Welcome to Crusoe’s island,” Charles greeted me, not even out of breath.

“Blasted MacNeils.” I dragged myself on to the grass at his side and lay there, face down and chest heaving.

“We had our own boat in the Flood,” Charles said. “But we men from Barra had to learn how to swim as well.” He grinned. “Here we are, Martin, both of us finally qualified doctors and free of all commitments, loose in the capital city. Imagine!”

I grinned at him. “Aye, imagine, Charles! Imagine what good we can do here, what cures we can affect among the sick and needy.” I watched two kittiwakes wheeling above the water, breathed deeply of the fresh sea air and lay back down. “We can maybe clean up some of the diseases in this city. God knows it needs cleansing in my area. I live in the heart of the Old Town, the Auld Toun, where the good and the great once lived, and now it is a veritable sink of disease, begging for a doctor.”

“And you are the very man to do it,” Charles flattered me. “Top man in your class in nearly all subjects. You are too idealistic though, Martin. You need to make money as well.”

“As long as I have enough to live,” I said, “I don’t need more.”

Charles and I had met on our first day in the Glasgow School of Medicine, and immediately became fast friends, despite our geographical differences. We roomed together in various less-than-salubrious parts of Glasgow, and both decided to further our careers in Edinburgh, rather than returning to our respective homes. Now we were meeting for the first time in weeks, but without any of the awkwardness that occasionally blights such reunions.

We lay for a while, enjoying each other’s company without saying a word as the waves surged and broke a few feet away until Charles broke the silence. “I’ve told you your only weakness, Martin. Now you must tell me mine.”

“Women,” I said solemnly. “Women like you and you like women. You will have to find a good woman and settle down rather than spreading yourself among many women who are anything but good.”

Charles laughed. “I was doing good, Martin, keeping the flashtails in work.”

I shook my head, for Charles’s reputation among the Glasgow prostitutes was legendary.

Charles glanced at the mainland. “The tide will be ebbing soon, and people will be able to walk out to this island. It’s tidal, you see.”

“We’d best leave before then,” I said.

“An hour yet,” Charles said. “Are you going to set up your practice from the house?”

“No.” I shook my head. “I want somewhere separate, if I can.”

“I have a practice in the New Town,” Charles said. “In Thistle Street.” He turned to face me. “I found a sponsor, an elderly doctor and another University of Glasgow man, who wishes to pass on his patients to me.”

I could only hide my jealousy behind a smile, although, in truth, I wished nothing but success for Charles. “I am sure that will prove very popular,” I said. “The New Town is the heart of respectable Edinburgh. You could not find a better place to work, and you’ll soon build up your reputation.”

“I hope so,” Charles said. “As will you, once your patients learn about you.”

“I hope so, too.” I lay back, luxuriating in the sunlight. “Lack of finances may delay that day.”

Charles rolled over on to his face and chewed on a stalk of grass. “There are methods to alleviate that problem,” he spoke around his grass. “You know that I was not born into money.”

I did know that. Charles was one of these rarities, a man who had raised himself from a Hebridean cottage to above respectability. “However did you manage?”

“By skirting the edges of fate,” Charles said. “One cannot rise in this world solely by hard work. One needs an influential patron, which I was fortunate enough to find. But even then, one must step outside the normal bounds of society and take to chance.”

“Chance?” I asked carelessly, watching a pair of black-headed gulls circle overhead.

“Games of chance.” Charles looked at me sideways. From behind a screen of grass, he looked young, with his freckled face, devil-may-care grin and bright blue eyes.

“Gambling,” I said.

“Exactly so.” Charles winked at me. “If one hits a winning streak, one can pocket a small fortune.”

My Presbyterian soul rebelled against such things. “My father called playing cards the Devil’s Bible,” I said.

“Your father was a good man,” Charles said. “How much did he leave you when he died?”

“Not a farthing to scratch myself with,” I said. “Father was a tenant farmer at the foot of the Cheviot Hills and laboured every day of his life just to survive.”

“Pious poverty does not help one make one’s way in this world.” Charles wriggled himself into a more comfortable position.

“The MacNeils were ayeways pirates,” I said, trying to prick his smug bubble.

“We were,” Charles agreed, unperturbed. “I am a member of a certain club in Edinburgh if you ever wish to join.”

“I won’t,” I said, searching my brain for something to alter the subject, for I did not care to think of Charles indulging in the devil’s playground. My thought must have transferred to him, for he shifted position, affording me a splendid view of his back, tattooed buttocks and legs. I had never examined Charles’s tattoo before, although we shared a room when we were students in Glasgow, but now I found myself staring at his right hip. “Where did you get your tattoo, Charles?”

“In a whaling ship off Greenland,” Charles said. “Last year. You’ll recall that I signed articles on a Leith whaling ship to raise finances and gain experience.”

“I remember,” I said.

Charles laughed, looking over his shoulder at his right hip and buttock, where the tattoo stood out against his pale skin. “My crewmates thought it would be fun to have an initiation for the Greenman surgeon.”

“It’s an interesting design,” I said. “Interlocking lines, like somebody wove a pattern on your body.”

Charles laughed again. He had a very distinctive laugh that started with a low gurgle and rose in pitch. “I can’t say that I’ve ever studied it! An Orcadian drew the design and somebody else marked it in.”

I left it at that, for even a doctor does not wish to examine that part of a man’s anatomy. However, the design remained in my mind.

“Are you ready to swim back?” Charles had been studying the tide with all the acumen of a Hebridean. “If we stay here much longer, somebody might walk out and catch us in nature’s garb.”

I sat up, somewhat reluctant to return to reality after our relaxing time on the island. “Come on then, Charles.”

We swam to the mainland with more decorum than we had shown on our outward excursion, to find the ebbing tide forced us to walk 100 yards from the edge of the sea to the whins. I was laughing at some sally of Charles’s when I saw the group of three people. They were about 200 yards from us but walking briskly in our direction.

“People,” I warned.

“I see them,” Charles said.

“They’re approaching our clothes.” I began to hurry, moving in a half-crouch to conceal as much of my person as possible. We were right in the open when I heard the unmistakable light tones of a female. “And there’s a woman among them.”

“Two women, I say.” Charles did not sound concerned. “This beach is well known as a place where men bathe,” he said. “Women should keep their distance or be prepared to see naked men. Or perhaps that’s why they are here!”

I was not as blasé as Charles, so increased my speed, yet I had hardly reached the shelter of the whins when one of the approaching party pointed to us.

“I say,” she said, with a tone that may have been either wonder or delight. “Would you look at that?”

As I hurriedly hauled on my clothes, the deeper voice of a man broke in.

“Turn your back at once, Evelyn, and you too, Mrs Swinton.”

I hurried, even more, covering as much of myself as I could before the party came any closer. When I looked sideways, Charles was casually dressing without any pretence at concealment. I must admit a moment of envy, for surely he had nothing of which to be ashamed.

There were three people in the party, one middle-aged man, a middle-aged woman whom I took to be the man’s wife and the most attractive young woman I had ever seen. I instinctively knew the younger woman was the daughter. The man was looking at me with a surprisingly benevolent smile on his face, his wife was pointedly looking in the opposite direction and the girl, the one who interested me the most, was staring at Charles’s Apollo-like physique.

I lifted my staff and stepped sideways to shield Charles’s still imperfectly clad person. “I do apologise,” I said. “We did not intend to cause any offence.”

“The fault is ours, if anything,” the lady said, still staring at Cramond Island as if she had never seen such a thing before. “I had heard that gentlemen used this beach for bathing but had not expected to find it occupied.” She gave a brief laugh. “I hope we have not caused you any embarrassment, although I do assure you that we did not see anything untoward.”

As I tapped my staff on the ground, the daughter looked at me for the first time. I saw her eyes widen as she smiled. “I am Evelyn Swinton,” she said with a sweeping curtsey. “This is my father, Mr James Swinton and my mother, Mrs Eliza Swinton.”

“I am Martin Elliot.” I met her curtsey with a bow. “And my ill-clad companion is Charles MacNeil.” She had the most marvellous grey eyes and I swear they were laughing at me, although they did flick sideways towards Charles for a second, no doubt to check his progress in dressing.

There was a few seconds of mutual bowing and curtseying, with a curious seagull watching from the shelter of the whins before Mrs Swinton spoke.

“Well, gentlemen, we are sorry to disturb you.” She glanced at her husband. “We will leave you in peace.”

“Oh, no, mother.” Evelyn touched her mother’s arm, with her gaze still fixed on me. “We must apologise properly by inviting these gentlemen to visit.”

Mr Swinton’s expression altered. His eyebrows rose, he glanced from Evelyn to me, then to Charles, and his lips twitched in a smile. He nodded. “Shall we say next Tuesday at five?”

“That would be admirable, sir,” I said.

Mr Swinton nodded. “Queen Street,” he said. “The house with the green door.”

“Nothing formal,” Mrs Swinton said, looking at us at last. “Pray, don’t dress up.”

“But do come dressed,” Evelyn said, for her mother to award her a sharp elbow and a hissed rebuke.

I smiled, for I do like a girl with a sense of humour, and bowed again, unwilling to admit that I possessed no formal clothes. As the Swintons walked away, I watched Evelyn. I knew she would turn around when she reached the wind-gnarled elder tree and was waiting with my smile and a raised hand. I gave another little bow, to which she had no time to respond before her mother pulled her away, rather sharply, I thought.

“Well, Martin,” Charles said. “You made an impact there. I thought you were always shy with girls.”

“I am,” I said, tapping my staff on the sand. “But perhaps not with that one.”

“Perhaps not,” Charles said, looking at me thoughtfully. “I might have to challenge you for the fair Miss Swinton.”

“You would not win,” I said, for already I felt affection for that lady. “I want her for myself.” I did not mention her sidelong glance at Charles.

I remember that afternoon on the beach as one of the happiest days I spent in Edinburgh, yet even then I was aware that the seeds planted were not all of the healthiest variety.

Chapter 3

Now that I had a home address, it was easier to find rooms for a surgery. I was very fortunate, for an elderly doctor had died, leaving his premises unoccupied and I saw the advertisement in the Caledonian Mercury.

It was a strange sequence of events, for I had flicked through the paper without noticing anything of interest, and laid it down on the floor beside my chair. I prepared to go for a walk and lifted my staff, but the thing seemed to have a life of its own. It slipped from my hand and rolled until the carved head rested on top of the newspaper. Only then did I notice the advertisement, as if the rounded head had indicated the place.

To Lease

A prime set of rooms in the historic Grassmarket. This establishment was the surgery of the late Doctor Walter Ogilvie and is complete in every way for a doctor’s surgery. It can also be easily adapted for use as living accommodation or any other commercial or business purpose.

For further details, apply to Messrs Mackay and Malvern, Lawnmarket.

“Good God,” I said. “How ever did I miss that?”

Lifting the staff, I left my house immediately to find Messrs Mackay and Malvern. I exchanged the echoes of the courtyard for the noises of the street, with the clatter of horseshoes on granite cobblestones, the clamour of blacksmiths working with red-hot iron and the chatter of a thousand people. I breathed deeply, inhaling the various scents of Edinburgh, not all of them pleasant. There was the scent of smouldering hoof-horn as a farrier fitted a horseshoe, the sharply ammoniac stink of human and animal urine, the constant smell of human sweat and the sweet invitations of whisky from the publics and spirit palaces that sat on every corner. I savoured each sight, smell and sound like a new experience and wondered why I had not noticed them before, or rather why I had taken them for granted. Life was scintillating, with so many adventures beckoning at every close-mouth and new friendships waiting with every smiling woman.

Tapping my staff on the ground, I strolled up the street, nodding amiably to anybody who caught my eye. Most returned my greetings, although one very respectably dressed gentleman gave me a glower in return. My surge of anger was unexpected, and I had to fight my desire to swing the staff at him and stride away. I seemed to be in the grip of new passions now, veering from extreme benevolence to sudden, nearly uncontrollable rage.