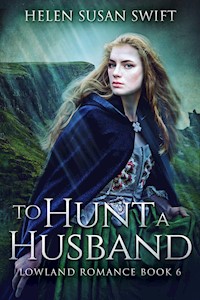

2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Next Chapter

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

At 22 years old, Robyn feels she is fast becoming an old maid. There are some eligible men in rural Midlothian, but Robyn has some competition from her particular friend, Amy.

Already engaged to a man she no longer loves, Robyn sets out to hunt for a husband in a countryside racked by social unrest.

Could her man be the collier hunted by the police - or the tall golfer? And who is the messenger who seems to appear just when he's not wanted?

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Ähnliche

To Hunt A Husband

Lowland Romance Book 6

Helen Susan Swift

Copyright (C) 2020 Helen Susan Swift

Layout Copyright (C) 2020 by Next Chapter

Published 2020 by Next Chapter

Edited by Elizabeth N. Love

Cover art by Cover Mint

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the author's permission.

Chapter One

Midlothian, Scotland, September 1842

There is little more delightful than to rise in the early morning and watch the sun wake the world. It was my habit to do so, lifting the hem of my skirt clear of the dew-damp grass as I strode up Roman Camp Hill, or the Camp as we called it, with the laverocks sweetening the air with their calls. I loved the freedom of movement, the sense of being alone with nature, and the feel of autumn air against my face.

That morning started no differently. I rose, dressed hastily and left the house by the side door, breathing deeply of the crisp air. Winter Lodge stood on the flanks of the hill, with our grounds spread around us and the slope rising in a succession of small fields and patches of woodland. High above, stars faded in the abyss of the sky, little eyes of God watching over us. I wondered at the vastness of the cosmos and what may lie up there, stumbled over a tuft of grass and berated myself for not paying attention.

As I jammed my hat hard on my head, I heard voices floating towards me, looked up, saw two figures approaching, recognised the taller, and continued.

“Good morning, Miss Moffat,” William Flockhart greeted me, while the man at his side gave a shy smile.

“Good morning, Will,” I replied. We knew him as Wild Will, for he spent all of his life out of doors, either living rough on the local hills or on the tramp to see the world beyond the confines of Midlothian. Brown of face and rough of clothes, he was a local character who, rumour claimed, had never entered a building for 20 years.

“Good morning, Miss Moffat.” The second man doffed his low-crowned hat as he spoke.

“Good morning,” I replied. I did not know the fellow, although I had seen him in the streets of Dalkeith and among the colliers of Winterhill. He was an open-faced coal worker with steady eyes, one of my father's tenants.

As Will and his companion strode downhill, I continued my ascent of the Camp, enjoying the stretch and pull of my muscles until I reached my tree. My father had planted that horse-chestnut on the day of my birth, two-and-twenty years ago. Father had chosen the most splendid of situations, with a panoramic view that stretched from the eastern pyramid of North Berwick Law to the fertile fields of Fife across the Firth of Forth to the north and westward over the Midlothian plain to the Pentland Range. On a clear day, I could even see the distant triangle of Schiehallion, the sacred mountain of the Caledonians in far-off Perthshire. However, the day that my life altered was not clear in any way, with the sun struggling to dissipate the thin haar easing from the Forth.

The first sign that my life's ordinarily serene pattern was about to change sat astride his horse underneath my tree.

“Well met, my lady.” The gentleman doffed his hat most gallantly. “I did not expect to meet anybody up here at this hour, particularly not such a handsome young lady as yourself.”

“I come here most mornings, sir,” I said, bobbing in a curtsey as I examined the stranger. He was handsome enough, in a rough-hewn way, with a weather-beaten face under his tall hat. His eyes held my attention as they laughed at me.

“Do you, indeed, ma'am?” he said. “You must be a local lady to make such an arduous climb.”

“I don't find it arduous, sir,” I said. “It is more of a pleasure than an imposition.”

The man's nod was strangely unsatisfactory as he continued to survey me.

“And you, sir,” I said. “You are not a local man, yet you also make the climb.”

“Chetak made the climb,” the man patted his horse's neck. “I merely sat astride her.”

“I see.” I was growing tired of this glib stranger's presence at my tree. “Did you come here merely to admire the view?”

“No, ma'am,” the stranger said. “I came here to learn the lie of the land.”

Well, that was honest. “You could not have come to a better viewpoint,” I admitted grudgingly.

We stood in silence for a moment, watching dawn spread across Midlothian, or Edinburghshire, to give its other name. Some of the towns were already awake, with lights in Bonnyrigg, Lasswade and Penicuik, while the tiny collier communities seemed never to sleep as the men and women toiled long hours underground.

“This is a mining area,” my handsome stranger said.

“Mining and farming,” I found this man increasingly wearying. “With some manufacturing. Do you have business here, Sir?”

“I have business here. You must know a great deal about the place.”

“I know a little,” I replied, hoping he would leave soon so that I could enjoy my tree in peace. “Do you have a name, sir?” I was uncomfortable in his presence.

“I do,” the man replied with a smile and a small bow from the saddle.

“In this part of the world,” I said severely, “it is the custom for a gentleman to introduce himself to a lady.”

“Indeed, ma'am?” My handsome man's eyebrows rose in pretended surprise.

“Indeed, sir,” I countered.

“In that case, ma'am, I am Adam Carmichael.” He bowed from the saddle again, with his eyes gently mocking.

“It is a pleasure to make your acquaintance, sir,” I curtseyed in reply.

“In this part of the world, is it also the custom for ladies to respond with their name?” Adam Carmichael asked.

“It is,” I said. “I am Robyn Moffat of Winter Lodge.” I indicated our house, the roof of which could be seen as the light slowly strengthened.

“A pleasure to meet you, Miss Moffat. Or is that Mrs Moffat?”

“It is Miss Moffat,” I told him.

Mr Carmichael bowed again, bending from the waist, so his face came momentarily closer to mine. “You will be Mr Thomas Moffat's daughter, I think?”

“I am,” I said, slightly surprised that a stranger should know Father's name.

“Pray tell me,” Mr Carmichael continued, all questions now, “as a local lady, have you noticed any unusual disturbances in the area of late?” Although the humour remained in Mr Carmichael's voice, his eyes were suddenly sharp.

“Disturbances?” I wondered at the question. “Nothing out of the ordinary.”

“Even with the colliers?”

I thought before I replied. “The colliers have withdrawn their labour, but there have been no disturbances worthy of the name.”

“The colliers have indeed withdrawn their labour.” All the humour had vanished from Mr Carmichael's face. “Will that affect you?”

“I can't see why it should,” I replied, slightly tartly. “I am not a collier.”

“Do you know any such men?” Mr Carmichael was challenging in his questioning.

I decided I no longer wished to converse with Mr Carmichael. “My circle of acquaintances is hardly your concern, sir,” I told him.

Mr Carmichael straightened in the saddle. “You are quite right, Miss Moffat.” The humour was back, if a little less pronounced than before. “I should not have asked. And now I must leave you,” he said. Only then did I see the long pistol he carried at his saddle, and I wondered what sort of man this Mr Carmichael was that he needed a gun to ride on Roman Camp Hill.

Erect in the saddle, he rode away, skirting the edges of the fields that led downhill, past Winter Lodge and onward in the direction of Stobhill and Gowkpen. I watched him for a while, wondering who he might be, then I leaned against the trunk of my tree, as was my practice. Nevertheless, my brief meeting with Adam Carmichael left me slightly unsettled, so it was with a bad grace that I returned downhill, following the trail I had made through the fields. For some reason, I could not get Mr Carmichael out of my head until I startled a lone hare that jinked across the ground at my side. I watched him for a long minute, which quite restored my good humour so I could return the gardener's greeting with a cheerful wave.

Winter Lodge was awake when I returned, with the servants all a-bustle and the aroma of breakfast greeting me when I opened the front door.

“Good morning, Robyn.” Father looked up from the newspaper to greet me. “Did you enjoy your walk?”

“Not as much as usual this morning.” I slid into my place at the table, helping myself to a slice of toast. “There was a strange man at my tree.”

“Oh?” Father lowered his paper at once. “What sort of strange man?”

“A gentleman named Adam Carmichael who asked me about the colliers. He knew your name.”

Father laid his paper aside. “Many men know my name. Perhaps you should refrain from taking your morning walk for a while, Robyn. These are troubled times, and I don't like the idea of strange men talking to you. What was he saying?”

“He asked about the colliers.”

“What did he ask?”

I had seldom seen Father look so serious. “He asked me if there had been any disturbances and if I knew any colliers.”

“I see.” Father returned to his newspaper. “You'd do well to avoid gentlemen such as Mr Carmichael, Robyn.” He spoke from behind the shelter of the printed pages. “If you insist on walking up Camp Hill, let me know, and I shall accompany you. Or one of the servants. Or perhaps Andrew Dewar or even Hugh Beaton.” Lowering his paper again, Father fixed me with a steady look. “Andrew Dewar would be more respectable although I think Mr Beaton is the better man. He plays golf, and no man who plays golf can be all bad.”

“Yes, Father,” I agreed meekly, although I had no intention of giving up my solitary morning walks to accompany a hacking golfer. Although father had a set of clubs somewhere, I had never known him ever take them for a visit to a golf course.

“I am betrothed to Andrew Dewar,” I reminded him, “not Hugh Beaton.”

“Then walk with him, if the sedentary Mr Dewar decides to rise from his bed at that hour of the morning,” Father replied from behind his paper.

I agreed. Andrew was notoriously lazy, so much so that I was not sure if he still liked me, or if he merely could not muster the effort to find somebody more to his taste.

“Someday Andrew Dewar will make his attachment to you official, Robyn,” Father said, “so unless you find a better man before then, you can reconcile yourself with a lifetime with his peculiar practices.”

I smiled, for Andrew and I had agreed to marry when we were still very young. “I told him once that I would only marry when he brought me a special ring from Paris,” I said. “Although Edinburgh would do.”

Father shook his head and returned to his newspaper. “There is little chance of that scoundrel venturing as far as Edinburgh unless somebody prods him with a pitchfork. You will have to settle for Dalkeith.”

“I'd accept Dalkeith.” I looked up as the door opened.

Mother walked into the room, half-dressed and with strands of hair hanging loose from her turban. “There you are Robyn!” She greeted me as if I had been exploring darkest Africa rather than merely walking on the hill behind Winter Lodge. “Are you seeing your young man today?”

“I rather thought I would accompany you to Dalkeith,” I said. “I intended to help out at the ragged school, unless you had other plans, Mother.”

“No,” Father said at once. “You won't go to Dalkeith today.”

“No? Why ever not?” Mother asked, vigorously towelling her hair with her turban. Lifting a knife, she looked at her reflection in the blade, sighed, and continued with her assault on her hair. “I look as if somebody's dragged me through a hedge backwards. Why shouldn't we go into Dalkeith today, Moffat?”

“There might be a disturbance,” Father said.

“A disturbance?” Mother had a habit of repeating Father's words. “How strange that you should think that. What sort of disturbance?”

“Colliers,” Father said.

Mother and I looked at each other in wonder. “Colliers,” Mother repeated as if that answered all the questions that crowded into my head.

I nodded sagely. “Ah. That Carmichael fellow mentioned colliers.”

“That is not surprising.” Father did not lower his newspaper. “There is nothing wrong with your appearance, my dear, but I forbid you to go into Dalkeith today.”

When Mother raised her eyebrows, I knew what she meant. I smiled in response and finished my breakfast, suddenly eager to join my mother in Dalkeith. A disturbance might break the monotony of rural life.

* * *

“Miss Moffat!” I had not expected to see Andrew that morning so looked up with a smile when he crunched across our gravel path towards me. As always, he looked supremely smart, with his low hat at a rakish angle and a look of curious disbelief on his face. “I had hoped to see you here.”

“This is my home, Mr Dewar,” I said, gently humorous. “I am often to be found here.”

Andrew gave an uncertain smile. “I know, Miss Moffat. I meant you might be away.”

I did not pursue that topic. “It is good to see you again, Mr Dewar.”

“Thank you.” Andrew hesitated, as if nervous, although we had known each other since childhood. “I am going to Dalkeith today.”

“Oh?” When Andrew gave me no more information, I asked gently: “Why is that, pray?”

“I have something rather special to do there.”

“Indeed?” I raised my eyebrows. “What sort of special is that, Mr Dewar?”

“You may learn by-and-by,” Andrew told me, with what I think he hoped was a mysterious smile.

“I think I can guess,” I said as my heart began to speed up, thinking of the ring I had mentioned to Father.

“You two!” Mother bustled out of the door, all orders and warmth. “How long have you known each other now?” She stood on the third top step, from where she could look down on us both.

“A long time,” I said, trying not to smile at the expression on Andrew's face.

“A long time,” Mother repeated, “yet you are still so formal! Call the poor boy by his Christian name at least, and you, Mr Dewar, my daughter's name is Robyn, as you know full well.”

“Good morning, Andrew,” I said, smiling as I dutifully obeyed Mother.

“Good morning,” Andrew replied with a little bow, added “Robyn,” turned away and marched down the path, kicking up so much gravel on to the lawn that our gardener would not be pleased.

“He is a strange fellow,” Mother said, with a shake of her head.

I could not disagree. Andrew Dewar was a strange fellow with a unique way of doing things. I still liked him, however, although I could no longer find that extra spark that transformed liking into love.

“Come, Robyn,” Mother said. “We have things to do.”

Chapter Two

Dalkeith is the market town of Midlothian, a bustling place of inns, merchants and small businesses. It is a town where farmers buy and sell, innkeepers charge too-high prices for their goods, lodging houses cater for travelling shearers, curlers play their roaring game, cricketers cricket, and an annual games attracts thousands of spectators and competitors. At one time or other, all the people from the countryside will gather in Dalkeith, including the Moffat women from Winter Lodge. That late September day of 1842 Dalkeith was even busier than usual for it seemed that every collier in the world had congregated in the town.

“Your father was right,” Mother said as she looked out of the window of our coach. “There are hundreds of colliers here. What in the world could have induced them to gather in such numbers?”

The colliers were indeed in large numbers. Everywhere I looked, colliers were standing in small groups, or marching purposefully this way and that, or talking in earnest knots at street corners. Although they were all dressed as respectable people, I knew they were miners by their appearance and demeanour. Muscular men with set, pale faces from working underground, many carried the blue scars of old injuries, while most wielded a walking stick. I recognised a few faces as men who worked in our pit at Winterhill, although I would be hard-pressed to put a name to them.

“Perhaps we should go home,” I suggested.

“Nonsense!” Mother gave me a friendly poke in the ribs. “They're only men, and some are our tenants anyway. Come along, Robyn. We will do an hour or so teaching at the ragged school. After that, I wish to visit a shop or two, and no man alive will stop me, not your father and certainly not a group of miners.”

Nothing loath, I obeyed. Although I must admit to a certain nervousness as I walked past the groups of colliers. However, none gave me so much as a second look – they were so engrossed with their own affairs. Indeed one or two lifted their hats with a polite, “Good morning, Mrs Moffat, good morning Miss Moffat,” to which we responded in kind.

The ragged school was quiet that morning, with fewer children than usual, and the middle-aged teacher distracted by the crowds outside. Mother and I did our best, reading to the infants and trying to teach the basics of writing as the teacher continually turned to stare out the window.

“We'll finish early today,” the teacher said at last. “I am a little concerned about the safety of the children with all these colliers in the streets.”

“If I know colliers,” Mother said, “they will pose no danger to little children.”

“I am not so sure.” The teacher had made up her mind, so we gentlewomen helpers had to comply. We ushered the pupils outside where they happily scattered among the colliers.

“More time for the shopping.” Mother led me at a fast pace towards the centre of Dalkeith. As we entered the first of the milliner's shops, the colliers began to move, although I had not heard anybody give them an order.

“Where are they going?” Mother asked in a tone of wonder as if hundreds of grown men could not decide their own movements.

“Up that close,” I pointed to a narrow lane that ran off the northwest side of the High Street.

“So they are,” Mother said, and for some reason not unconnected with curiosity, we found ourselves walking up the same close in the wake of the colliers.

“Now they are entering that building.” I pointed to the Freemasons' Hall, a building that hardly appeared 100 years old.

“Maybe they're all Freemasons,” Mother said, and promptly lost interest as a length of purple linen in a window took her attention. “Now that would make a fine dress for your wedding if Andrew Dewar ever makes up his mind to ask properly.”

We spent some time in the Dalkeith shops, for in truth living in Winter Lodge without distractions could be a mite tedious, and when we emerged, the town was like nothing I had ever seen before.

“Mother!” I stopped in some alarm. “Look at the army.”

Opposite the closed doors of the Freemasons' Hall stood rank after rank of soldiers, with their scarlet uniforms bright in the autumn sun and their fists closed around long brown muskets. The officers stood in front, tall, erect men with long swords at their waists and the power of life and death in their command.

“Stay close, Robyn.” Mother's hand gripped my arm. “We'd best be away from this place.”

For one minute, I wondered if Adam Carmichael would be present to witness the disturbance, and then I heard the tramp of marching feet and dismissed him from my mind. With so much happening in Dalkeith that day, it was natural that a crowd should gather, with women and men clustering around the Freemasons' Hall, staring at the soldiers while keeping a wary eye on their muskets.

“What's happening?” The words rose to the grey skies above.

“What's to do?” a woman screeched. “Look at all the sojer-boys!”

“What the devil is the army doing here?”

Perhaps the only person who could fully answer that question was the Duke of Buccleuch, the principal local landowner, for he was a dominant figure, giving orders to the military and to the body of 20 or so special constables who also now poured into the centre of the town. In their long, blue, swallow-tail coats and glossy top hats, the specials looked quite efficient.

“Come away, Robyn.” Mother's hand was firm on my arm.

“Not yet,” I insisted. “I wish to see what's happening.”

“It's not ladylike,” Mother said, looked at me and nodded, vaguely smiling. “But I am also curious.”

Squeezing into the entrance to a common close, we waited and watched. Luckily we were both fairly tall for women and, if we stood on tip-toe and stretched our necks, we could watch events over the heads of the equally curious crowd.

“I hope none of our neighbours can see us,” Mother said.

“If they do,” I reasoned, “then they must also be watching.”

The duke, with his chamberlain, Mr Moncrieff, marched to the front door of the Freemasons' Hall to demand entrance. The buzz of the crowd eased as people waited to see what would happen, and the soldiers seemed to take a collective deep breath. I saw one of the officers, a lieutenant I believe, put an expectant hand to the hilt of his sword.

“Oh, please don't let there be any trouble,” Mother said. “We should have left when we saw the army.”

“It's too late now.” I gestured to the crowd. “We'd never get through all those people.”

The hammer of the duke's fist on the door echoed around the street. I saw one of the soldiers fidget, with his hands moving to the trigger of his musket, and then I noticed Adam Carmichael in the crowd. He was on the opposite side of the street from us, sitting on Chetak and equally interested in watching. There was no humour in his eyes, which were darkly reflective.

“Mother,” I said. “There's the man I saw this morning.”

Hush, Robyn.” Mother's grip on my arm tightened. “Look what's happening.”

After initially refusing access to the duke, the colliers inside the hall eventually opened the door. Immediately they did, the duke and his chamberlain hurried inside, followed by a rush of the blue-uniformed special constables, all seemingly eager to be first in and all carrying their long staffs of office.

Special constables have a dark reputation for violence and ill-discipline. Unlike the full-time, disciplined and trained policemen who walk the beat and deal with every-day crimes such as petty theft and drunkenness, the specials are civilians recruited for specific events such as riots or disorder. Mainly from the respectable strata of society, they are often heavy-handed in their eagerness to restore what they see as the natural order. Knowing such things, I was more than a little shocked when I saw my Andrew Dewar among the blue-coated ranks that stormed into the hall.

“Mr Dewar! Andrew!” I could not help myself. I shouted the name without thought and immediately hoped that the noise of the crowd drowned my voice. As bad luck would have it, the crowd had hushed at that moment, and my shout rang out, clear as a church bell on a sleepy Sunday, right across the centre of Dalkeith.

Happily, most people were too intent on the unfolding drama at the hall to pay much heed, but Adam Carmichael turned his head my way. Looking directly at me, he frowned, as if trying to remember where he had seen me before, lifted a hand in brief acknowledgement, and returned his attention to the hall.

“He heard you,” Mother murmured.

“I know.” I was torn between watching Mr Carmichael and the drama in which Andrew was playing his part.

“Andrew heard you bellowing like a fishwife.” Mother was not referring to Mr Carmichael but Andrew. “Now he will wonder what sort of manners you have.” She shook her head. “It's best to let men think you are eminently respectable if you wish them to marry you, Robyn. After the event, it is not so important.”

“Yes, Mother.” I knew the rules of the hunt. Men pursued women until the women caught them. I only wished that Andrew was more ardent in his pursuit.

While I had been thinking of personal matters, the drama before us had continued. With Andrew and the other specials at his back, Mr Moncrieff read out the names of three of the colliers and demanding they surrender themselves to the law. Not surprisingly, none of the miners stepped forward, so, after an awkward pause, the duke and his entourage left the hall and waited outside. With special constables on one side of the street, tapping their staffs in their palms, and the army standing at attention on the other, it seemed that there would indeed be trouble in Dalkeith.

Fighting my nerves, I caught Andrew's eye and smiled. Trying to look tough and capable with his colleagues, he ignored me as if I were not there, which awakened the devil within me.

“Should I go and talk to Mr Dewar?” I asked.

“No!” Mother said at once. “I think we should leave here.” Despite her words, she made no effort to move. I knew that Mother liked a good drama as much as everybody else. Today's events would give her plenty of conversational material for the next few dull weeks in Winter Lodge.

Although Andrew did not glance in my direction, Adam Carmichael did far more. I could feel his eyes probing me as if wondering what on earth I was doing here. I looked up again, caught his gaze and smiled. Again he raised a hand in acknowledgement.

“That Carmichael fellow is watching me,” I murmured, responding with a small nod.

“I am not surprised,”' Mother said. “And with you making such a spectacle of yourself. He must be wondering what sort of daughter your mother brought up.”

I closed my mouth as the door to the hall opened, and the miners quietly emerged. The first man looked at the waiting specials, squared his shoulders, gripped his walking stick firmly and marched on, with others following behind.

“There won't be any trouble,” I said, and then the specials pounced. I was surprised at the energy with which Andrew grabbed one of the miners, holding him firmly as another special snapped handcuffs on the unfortunate man's wrists.

“That was your Andrew,” Mother said as if I could not see a man three yards in front of my face.

The specials arrested another of the colliers and lunged at a third. Rather than quietly submitting, this man eluded the clumsy grasp of the special, twisted away, cracked Andrew on the knuckles with his walking stick and ran. I blinked, for the escapee was the very man I had seen with Wild Will that very morning.

“Halloa! Catch that man!” Andrew raised the hue and cry.

“Stop, thief!” another Special shouted, and a dozen of the blue-uniformed men ran in pursuit of the fleeing collier.

“Come on, Robyn.” Mother took hold of my arm once more. “Let's get home. We've wasted sufficient time here.”

However, making our way back to the coach was not easy with what seemed like half of Midlothian either chasing the fugitive or obstructing those who were. We tried to negotiate a passage through the crowd, being buffeted by sundry people and saying, “Pray excuse me,” as loudly as decorum permitted without any discernible effect.

“Oh, this is no use,” Mother said. I could see that she was growing increasingly exasperated as the mob clustered around us. The cries of, “Stop thief!” “Murder!” “Help the unfortunate fellow escape!” or, “Catch that man!” resounded, with little boys running around in great glee and their mothers dealing out smacks and cuffs in frantic worry for their offspring.

“Are you all right, ladies?” Adam Carmichael reined Chetak in front of us, with that humorous gaze scanning us both. “Miss Robyn Moffat, we meet for the second time today.”

“We do, sir,” I even managed a curtsey amidst the chaos for Mr Carmichael's horse seemed to act as an island in the rush of people, creating a small oasis of relative peace.

“And you must be Miss Moffat's sister.” My gallant Mr Carmichael bowed to Mother.

“I am nothing of the sort, sir, as you are well aware.” Yet, despite Mother's hot words, her hand moved to straighten her hat, and I could see she was quite taken by Mr Carmichael. “I am Mrs Thomas Moffat, Robyn's mother.”

“A good day to you, Mrs Moffat.” Mr Carmichael lifted his hat. “If you stay close, ladies, Chetak and I will push through the crowd.” Mr Carmichael said. “Where are you heading, Mrs Moffat?” He diplomatically addressed Mother rather than me.

“The White Hart Inn,” Mother said. “We have left our carriage in the stable there.”

“The very place I am going,” Mr Carmichael said, touching his hat. “Pray, follow, ladies.”

Glad of the escort, we obeyed, walking meekly behind the horse as Mr Carmichael created a channel through the roaring crowd. When one group of drunken carters tried to bar his passage, Mr Carmichael leaned sideways from his saddle and slashed the most impudent across the shoulders with his crop. 'Move aside there!'

“That's the stuff!” Mother cried in full approval.

I said nothing, wondering what level of steel lay beneath Mr Carmichael's jovial exterior.

The carter turned around, eyed Mr Carmichael, decided not to protest and moved aside for us. Mr Carmichael pushed on through the crowd.

“Here we are,” Mr Carmichael guided us to the White Hart Inn. He stopped outside, dismounted with an effortless grace and lifted his hat first to mother and then to me. “I shall wait until you are safely away.”

“Thank you, Mr Carmichael, but there is no need,” Mother said. “We know the road from here.”

“In that case,” Mr Carmichael said, “I shall be on my way. I wish you both a pleasant trip home.”

“Thank you, sir.” Mother glanced at me. “I wish you a successful conclusion to your business, whatever it may be. You will have to visit us sometime in Winter Lodge, to allow me the opportunity to repay your kindness. I'm sure that Robyn would also be pleased to see you.”

I nodded, although I was not so certain if I would be pleased or not. There was something vaguely unsettling about Mr Carmichael, some tension beneath the urbane exterior.

Waiting until Mr Carmichael walked his horse away, Mother smiled. “So that was your Mr Carmichael, was it?”

“He is not my Mr Carmichael, Mother.”

“No, of course not.” Mother's smile was so superior that I knew she was planning something. “He should certainly be somebody's Mr Carmichael.”

Our driver was in the taproom of the White Hart, quaffing whisky and quite forgetting about his passengers until Mother reminded him of his position and sent him off with a flea in his ear.

“You have five minutes, George, to bring the coach to the front of the hotel.”

“I thought you'd be another hour, Mrs Moffat, with all this confusion.”

“We do not employ you to think, George, but to drive the carriage and do as you are told. Five minutes and not a second more.”

It was only four minutes before George drove the coach to the front of the inn. Giving him a nod of approval, Mother boarded first, with me following. Hauling aside the curtains, I peered out of the window.

“Don't stare, Robyn,” Mother said. “Simply tie open the curtains and sit back in your seat, as I do.” She gave me a wink. “That way, you can look outside without anybody seeing your face.”

“Yes, Mother.” Settling back in the worn leather seat, I looked outside in time to see Mr Carmichael still there, sitting on Chetak and watching our coach emerge from the courtyard. I am unsure whether he saw me, despite my precautions, but when he lifted his hand in farewell, I was sure he gazed directly into the coach, with deep seriousness shading his mocking eyes.

* * *

I lay in bed that night, knowing that my life had changed, although I did not quite know how, or why. My mind whirled with images of Mr Carmichael beside my tree, Andrew in his smart blue uniform and the scarlet ranks of soldiers waiting outside the Freemasons' Hall, together with the face of that unfortunate collier as he fled from the police. Remembering that Andrew had mentioned he was going to Dalkeith for something special, I sighed. Rather than searching for a ring to seal our engagement, he had become a Special constable.

I sighed again. Unable to rest, I rose from the bed and paced my room until the creak of floorboards woke half the house.

“Get to sleep, Robyn,” Father shouted. “You'll be tired and out of temper in the morning.”

Knowing I could not sleep, I pulled on a pair of boots, slipped my winter greatcoat over my nightclothes, jammed a hat over my unruly hair and left the house. I did not intend to go far, merely to walk around the grounds until I eased the confusion inside my head. I was fortunate that the moon was nearly full, casting a friendly light over our smooth lawns with the splashing fountain, and casting shadows from the avenue of beech trees that lined our drive.

I paced up and down, soothing my mind as I tried to put order into the chaos within my head. I was so intent on my thoughts I barely heard the whistling owls or the barking of the deer from the woods a hundred yards to the east. Who was this Mr Carmichael, and what did I now feel for Andrew? I did not know. Mr Carmichael appeared the most courteous of gentlemen, yet he carried a long pistol at his saddle and had not hesitated to use force to part the crowd. I was not sure if he fascinated or repelled me.

As for Andrew? I continued to pace. Andrew and I had a long-standing arrangement that we would marry, with no date fixed. We were young when we made the pact, and my youthful ardour had cooled. Now I was unsure how I viewed him, or if I wished to spend the remainder of my life with a man I did not love, although I certainly did not dislike him. There were other men out there, Hugh Beaton for instance, or Derek Pringle.

With a breeze blowing clouds across the sky, the moonlight was fitful, sending shifting shadows over the ground. One moment there was darkness, the next light, so I was unsure if I had seen movement or not in the flicker of light at the head of the beech avenue. I watched, hoping for a deer or badger, for I do love to see the wild animals of the countryside. Instead, I saw the figure of a man darting across our lawn 100 yards in front of me.

“Oh!” I covered my mouth to stall my instinctive shout. My first thought had been to challenge the intruder, but I realised that action might be foolish. In the present disturbed state of the country, this fellow could be anybody, from a solitary poacher to a cracksman from Edinburgh looking to break into Winter Lodge. On the other hand, it might only be one of the servants returning home after some romantic liaison. I smiled at the latter thought, for the whole household knew that young James, the groom, was making sheep's eyes at one of the maids in Dalhousie Castle, a few miles down the road.

I stood still, prepared to run back to the house if need be and equally ready to say nothing if my nocturnal visitor was on some innocent pursuit. A stray poacher after a rabbit for the family pot did not concern me and, as for James, the best of luck to him, I say. We all need love in our lives, and that thought brought me back to my dilemma with Andrew.

What on earth induced him to join the Specials? I had never heard him express any interest in anything political. Indeed, I had never heard him express any interest in anything before, except maybe fishing. Andrew did not possess the most active of minds.

My thoughts were interrupted again by movement ahead of me. The man must have been lying prone in a patch of darkness and moved when the moonlight betrayed his position. This time I saw him distinctly as he shifted, bent double, across our lawn. I knew his face, if not his name, for he was the same fellow I had seen with Wild Will that very morning, and the same fellow the police had chased through the streets of Dalkeith.

At the same moment I recognised him, he also saw me. I had never seen such an expression of surprise cross a man's face as then.

“You,” I hissed, pointing to him.

“Miss Moffat!” He whispered my name, placing a finger across his lips to compel me to silence. “Please! It is you I have come to see.”

“Me? The police want you,” I said, but not so loudly that my voice carried.

“It's all right,” the man said, “I won't hurt you.”

“What are you doing here?” I had the sense to keep my voice down.

“I need your help,” the man said. “If the police find me, they'll throw me in jail.”

Glancing back at the house, I saw it was still in darkness. “What have you done?” I was not sure if I should shout for help or allow this man to gang his ain gate, as we say. That means go his own way.

“I've done nothing harmful,” he said, which was probably the answer any murderer or thief gave when first questioned about their activities.

Now, if he had been an ugly old man with warts and a bald head, I would probably have shouted, or run for help, for it is well known that the signs of depravity are visible on the physiognomy of any criminal. However, this man was, if not quite handsome, at least not unpleasing as to his countenance, and was about the same age as me or perhaps a few years older.

“If you've done nothing harmful,” I said, “why do the police wish to arrest you?” I thought that rather a pertinent question, given the circumstances of this fellow roaming around our lawn at one in the morning.

The man began to look agitated, glancing at our house and behind him, as if he expected a score of policemen to erupt from our shrubbery. “People say I've done wrong,” he said. “I'd be obliged if you did not tell anybody you've seen me.”

“I won't if you are innocent,” I said, rather enjoying the drama of the situation, and now feeling quite secure with this vulnerable and rather handsome young man.

“I am innocent of all crime. I swear it.”

“I believe you,” I said, nodding to add emphasis to my words. “Do you have a name?”

“I'm Matthew Juner,” the man said, after a little hesitation that made me wonder if he was telling the truth. He looked up as a shift of wind uncovered the moon once more and light glossed across the lawn, so we stood as exposed as if it were full day. He was tall for a collier, too, which was in his favour. “Please, I must hide.”

“Come with me,” I said, making a sudden decision to help this unhappy man, although I could not say why. “I know the very place.”

I led him off the lawn on to one of the narrow paths through the shrubbery, brushing past father's rhododendron bushes and down a steep, barely-marked track. “Where are you taking me, Miss Moffat?” Matthew asked.

“I grew up here,” I said. “I know every nook, corner and secret spot. I'll take you to a place where I used to hide when we played childhood games. Nobody ever found me there.” I favoured Matthew with a smile that was lost when a cloud concealed the moon. “It was my special place.”

We slithered down the path, with the steep incline compelling us to use our hands as well as our feet. At the foot of the path, a gale of a decade ago had blasted down an ancient oak, which effectively blocked the path.

“You see?” I said, “Anybody would think that the road ends here.”

Matthew nodded. “It looks like it.”

I smiled, quite comfortable in this man's presence. “Follow me.” Even in the dark, I could find my way through the small tunnel of branches that coiled around the oak to the near-overgrown path on the far side.

“Here we are,” I said, smiling. “Nobody has come here in years.”

“Thank you.” Matthew touched my arm, which was very forward of him, I thought. “I can't thank you enough.”

Even with September drawing to its close, the shrubbery at this corner of our policies was dense. After the mist of the previous day, it was also damp, so both Matthew and I were horribly wet before we reached our destination. It was an old folly, built by some long-dead ancestor a century or more ago, but still in a sound condition. Situated on the lip of a steep slope toward a small burn, the Winter Burn, the folly had a single arched door and three pointed windows, facing east, west and north respectively.

“You see?” I said proudly. “You are safe as houses here and can spy on anybody approaching.”

“Thank you,” Matthew sounded genuinely grateful. “Will told me you would help. He said you were always willing to support people in need.”

“Did he indeed?” I said, resolving to have words with Master Will in the not-too-distant-future. I hesitated, unsure what I should do.

“I won't be here long,” Matthew said. “I'll be off in the morning.”

“All right then,” I said. “I'll leave you alone now,” and for some reason, I added, “Good luck, Matthew.”

“Thank you.” Matthew gave a shy smile. “There is one more thing,” he said. “I don't like to ask.”

“Ask,” I said. “I don't like secrets.”

“There may be a man looking for me,” Matthew said.

“A policeman,” I guessed.

“No. A essenger-at-rms.”

I was familiar with the term but admitted I was unsure what a messenger-at-arms did.

“Have you heard of Sheriff Officers?”

“Servants of the court,” I said. “They evict people on the orders of the sheriff.”

“They do that and more than that,” Matthew said. “Well, messengers-at-arms are officers of the Court of Session, which means they serve legal documents and enforce court orders across Scotland. They can arrest anybody, anywhere, at any time.”

“Oh,” I said. “Why is this messenger-at-arms looking for you?”

“There is a High Court order to arrest me.”

Why?” I wondered if Matthew was a romantic highwayman or perhaps a murderer, this man who told me he had done nothing harmful.

“For encouraging the colliers to form a combination.”

That was neither romantic nor exciting. “That's not illegal,” I said.

“No, but the authorities frown upon it,” Matthew gave a twisted smile. “They can alter facts to make me seem guilty of things I have not done.”

I frowned, for we were a very respectable family, without any prejudice against the law.

“If I see a messenger-at-arms, I will tell you,” I said, after a moment's thought. How will I recognise him?”