0,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: E-BOOKARAMA

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

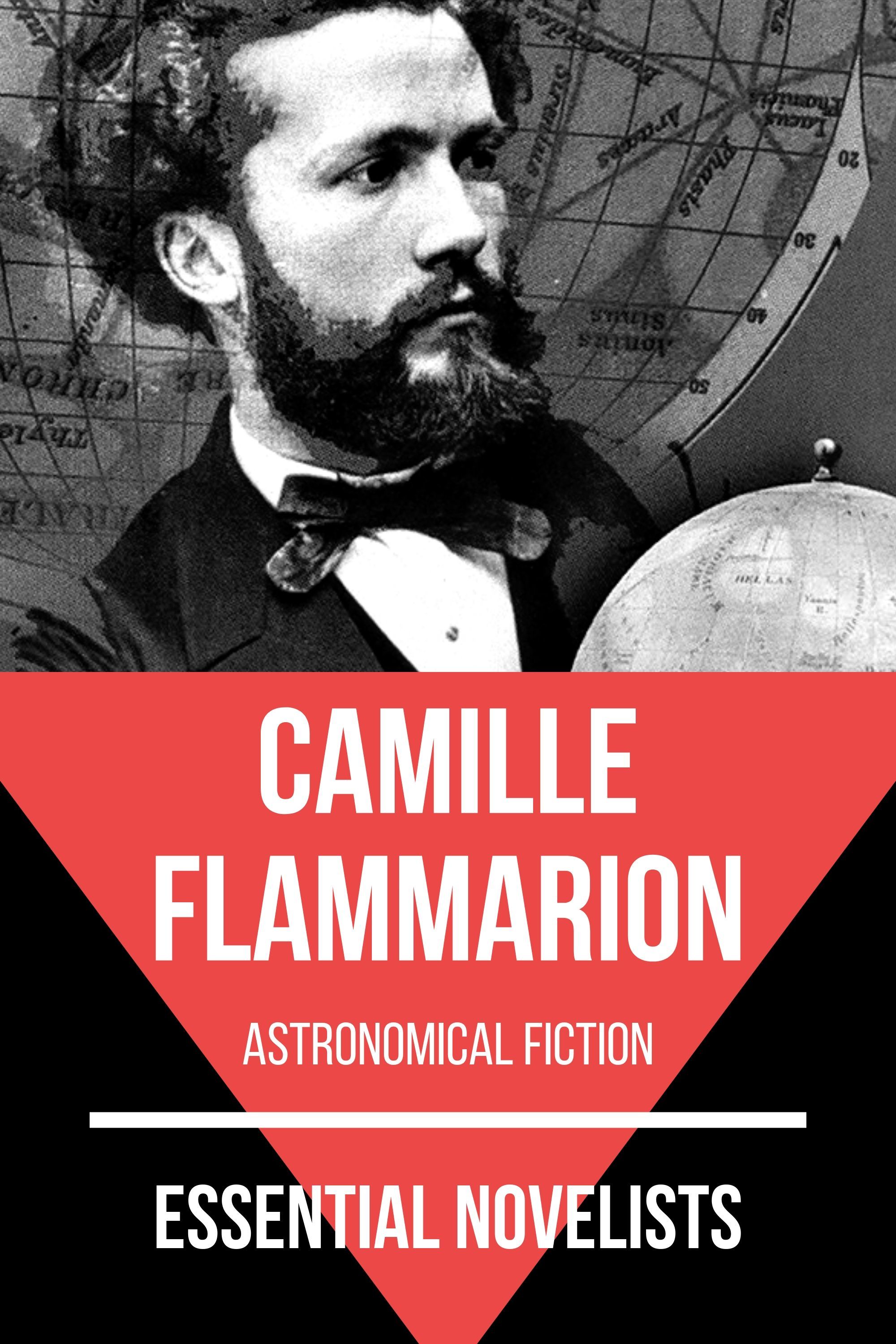

First published in 1922, "Death and its Mystery, Before Death" by French astronomer and author Camille Flammarion is the first volume in a series that looks at life beyond the grave. The other volumes are "

II: At the moment of Death" and "

III: After Death."

This series searches for proof of the existence of the soul and it considers lots of Flammarion's personal accounts.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2025

Ähnliche

Table of contents

DEATH AND ITS MYSTERY - Volume I : BEFORE DEATH

Chapter 1. The Greatest Of Problems – Can It Actually Be Solved?

Chapter 2. Materialism – An Erroneous, Incomplete, And Insufficient Doctrine

Chapter 3. What Is Man? Does The Soul Exist?

Chapter 4. Supra-Normal Faculties Of The Soul, Unknown Or Little Understood

Chapter 5. The Will, Acting Without The Spoken Word, Without A Sign, And At A Distance

Chapter 6. Telepathy And Psychic Transmissions At A Distance

Chapter 7. Vision Without Eyes – The Spirit’s Vision, Exclusive Of Telepathic Transmissions

Chapter 8. The Sight Of Future Events; The Present Future; The Already Seen

Chapter 9. Knowledge Of The Future

DEATH AND ITS MYSTERY - Volume I : BEFORE DEATH

Camille Flammarion

PROOFS OF THE EXISTENCE OF THE SOUL

Chapter 1. The Greatest Of Problems – Can It Actually Be Solved?

To be or not to be.

SHAKESPEARE.

ALTHOUGH I am not yet entirely satisfied with it, I have decided to offer today, to the attention of thinking men, a work begun more than half a century ago. The method of scientific experiment, which is the only method of value in the search for truth, lays requirements upon us that we cannot and ought not to avoid. The grave problem considered in this treatise is the most complex of all problems and concerns the general construction of the universe as well as of the human being – that microcosm of the great whole. In the days of our youth we begin these endless researches because we are full of confidence and see a long life stretching out before us. But the longest life passes, with its lights and shadows, like a dream. If we may form one wish in the course of this existence, it is to have been in some way of service to the slow but none the less real progress of humanity, that fantastic race, credulous and skeptical, virtuous and criminal, indifferent and curious, good and wicked, as well as incoherent and ignorant as a whole – barely out of the chrysalis wrappings of its animal state.

When the first edition of my book “La Pluralité des Mondes habites” were published (1862-64), a certain number of readers seemed to expect the natural sequel: “La Pluralité des existences de l’ame.” If the first problem has been considered solved by my succeeding books (“Astronomie populaire,” “La Planete Mars,” “Uranie,” “Stella,” “Reves etoiles,” etc.), the second has remained as open question, 1 and the survival of the soul, either in space or on other worlds or through earthly reincarnations, still confronts us as the most formidable of problems.

A thinking atom, borne on a material atom across the boundless space of the Milky Way, man may well ask himself if he is as insignificant in soul as he is in body, if the law of progress can raise him in an indefinite ascent, and if there is a system of order in the moral world that is harmoniously associated with the order of the physical world.

Is not spirit superior to matter? What is our true nature? What is our future destiny? Are we merely ephemeral flames shining an instant to be forever extinguished? Shall we never see again those whom we have loved and who have gone before us into the Great Beyond? Are such separations eternal? Does everything in us die? If something remains, what becomes of this imponderable element – invisible, intangible, but conscious – which must constitute our lasting personality? Will it endure for long? Will it endure forever?

To be or not to be? Such is the great, the eternal question asked by all the philosophers, the thinkers, the seekers of all times and all creeds. Is death an end or a transformation? Do there exists proofs, evidences of survival of the human being after the destruction of the living organism? Until today the subject has remained outside the field of scientific observation. Is it possible to approach it by the principles of experimentation to which humanity owes all the progress that has been realized by science? Is the attempt logical? Are we not face to face with the mysteries of an invisible world that is different from that which lies before our senses and which cannot be penetrated by our methods of positive investigation? May we not essay, seek to find whether or not certain facts, if carefully and correctly observed, are susceptible of being scientifically analyzed and accepted as real by the severest criticism? We want no more fine words, no more metaphysics. Facts! Facts!

It is a question of our fate, our destiny, our personal future, our very existence.

It is not cold reason alone that demands an answer; it is not only the mind; it is our longings, our heart also.

It is childish and may appear conceited to bring one’s own self upon the scene, but it is sometimes difficult to refrain from doing so; and as I have undertaken these laborious researches primarily in order to answer the questions of sorrowing hearts it seems to me that the most logical preface to this book will be furnished by some of those innumerable confidential communications which have reached me during more than half a century, begging with anguish for the solution of the mystery.

Those who have never lost by death some one deeply loved have never sounded the depths of despair, have never bruised themselves against the closed door of the tomb. We seek, and an impenetrable wall rises inexorably before the terror that confronts us. I have received hundreds of earnest appeals that I should have liked to answer. Should I make these confidences known? I have hesitated a long time. But there are so many of them, they reflect so faithfully the intense desire that exists to reach a solution, that it has now become a matter of general interest and my duty is clear. These expressions of feeling are the natural introduction to this work, for it is they that have decided me to write it. Nevertheless, I must apologize for reproducing these pages without alteration; for if they reveal the very souls of their sensitive authors, they also express themselves about me in terms of praise that it might well seem immodest on my part to publish. But this is only a personal detail, and consequently insignificant, especially as an astronomer, who realizes that he is an atom before the infinite and eternal universe, is inaccessible to and hermetically sealed against feelings of worldly vanity. Those who know me have considered me for many long years. My absolute indifference to all honors has abundantly proved this true. Whether I am considered great or insignificant, whether I am praised or criticized, I remain the distant spectator.

The following letter was written me by a distracted mother and has been reproduced literally. It shows how well worth while it would be at least to attempt to relieve suffering humanity. It is more than the science of doctoring the body, it is the science of healing the soul that must be created.

To Our Great Flammarion

Reinosa, Spain, March 30, 1907.

Monsieur:

I wish I might cling to your knees and kiss your feet while I beseech you to hear me and not reject my prayer. I cannot, I know not how to express myself. I wish I might arouse your pity, might interest you in my grief, but I should have to see you, to tell you myself of my own unhappiness, to paint the horror of what is passing in my soul, and then you could not deny me an immense compassion. What I have had to suffer before I could bring myself to commit this act of daring and indiscretion that resembles madness! Whence came the idea of addressing myself to our illustrious Flammarion, of asking him to console an unknown person who has no other claim upon his kindness than that of a fellow-countrywoman? It is because I am suffering! I have just lost a son, an only son. I am a widow and my only happiness consisted in this son and one daughter. Monsieur Flammarion, you would have had to know the beloved child I have just lost, to understand. I should have to tell you the story of the thirty-three years of his existence: then you would understand.

When at five years of age he was given up by all the celebrated physicians of Paris and Madrid, because of hip trouble, my poor husband and I sacrificed a brilliant position at Madrid and buried ourselves in a lonely country district in Spain in order to save this little boy who was the object of our devotion. For eight years he was ill and he was left lame! What he cost me in anxiety, care, sorrow, sleepless nights, anguish, and sacrifices it would be impossible to explain. But how dear and lovable he was! Brought up in a little carriage, petted and caressed, he was the most adorable child one could imagine. Oh, that childhood! How I wish I could get it back! At twelve years of age he no longer suffered from his leg, but he could not walk without crutches. What a grief this was to me, who had brought him into the world strong and well made! Later, at seventeen, he walked with only one crutch and a cane. At twenty, he was as handsome a lad as could be seen anywhere. If I dared, I would send you his photograph, so that you might see that my mother’s love exaggerates nothing. Everyone felt his charm; he had that gift of pleasing which can be neither defined nor explained. Men, women, children, old and young were charmed by I know not what that radiated from his person. Wherever I went with him, I was congratulated on the beauty and goodness of my son. People envied him. Ah! That was because he was as beautiful as he was good! His soul was all nobility, grandeur, generosity. Intelligent and spiritual, even-tempered and sweet in his disposition as he was, life with him was a heavenly dream, a continual enchantment. You will realize what this meant, Monsieur, when I tell you that at twenty he developed cystitis, which was certainly a return of the first trouble in his leg, and that this cystitis was the beginning of a whole chain of suffering of which only hell could give you any idea. I cannot understand how God, our Creator, can permit the human body to be so martyrized. Above all, when this martyrdom is inflicted on a good and innocent being like my son. All the great specialists were consulted again, but alas! none of them was able to cure him. He spent thirteen years alternating between periods of better and worse, preserving, in the midst of the most atrocious suffering, his sweetness, his goodness and even his gaiety, so as not to sadden others.

For the past four years he has scarcely suffered at all, and last year he was so much better that he believed he was cured. My poor husband had died in 1902. From that time my son had been the head of our little family: mother, sister, and himself. How happy we were!

Although we were obliged to work to supply our needs, life appeared very beautiful to us! My daughter had never wished to marry, so that she might devote herself to her brother, whom she adored. I was so happy in the love I saw that my children bore each other that I no longer feared death for myself, as I knew I should leave them together, not to be separated as long as they lived, living each for the other. And how shall I describe to you the tenderness of my son for his mother, of this mother for her son? Seek in heaven among the angels; seek above, among those worlds to which your gaze penetrates; seek among all the best and sweetest things that love can produce, and you will have only a feeble idea of the filial and the maternal love of these two. I dare not think of it. I dare not remember his eyes, his voice, when he looked at me and said, “Darling Mother!”

Last August it was proposed to him that he should visit a mine (he had acquired a taste for this kind of work and had been occupied with it for some time). He wished to take me with him. When we had reached a certain spot we were told that we should have to go on horseback to reach the mine. As I knew he had been forbidden to ride on horseback, because of his bladder, I refused; but my son assured me he felt certain he could make this trip without danger. We hesitated; we discussed it; I yielded.

Ah! Why can we never retrace our steps! This excursion so tired my son that he fell ill of gastric fever. He was in the hands of stupid and ignorant physicians who knew nothing of his condition and who let the months slip by while they said that nothing was the matter! A tumor attacked the bladder, the walls could not endure the strain: the bladder burst!

The tortures of hell are nothing to the tortures suffered by my unhappy son! A celebrated surgeon was called in. he did not arrive until twenty-two hours after the accident. My child had made all his preparations for leaving this world. They operated, but all hope was gone. The poor boy survived the operation for thirteen days; the surgeon had given him only twenty-four hours more. But my son, who understood his mother’s and sister’s grief, resisted, fighting bravely in spite of everything. What days, Monsieur! They gave us the measure of his greatness of soul.

Thinking only of us, of the consequences of his death to two women who would remain alone and without support in a foreign country, who would always mourn an adored son and brother, he tried in all ways to soften the horror of this situation. What he said to us in those supreme moments were the words not of a young man of thirty-three but of a saint, an angel, a superhuman being! Oh, that face tortured by suffering! Those eyes that seemed to see something of another world! And his mouth, twisted by pain, still trying to smile, his hand pressed mine as he said: “Good-bye, darling Mother, good-bye! I have loved you so dearly! Do not forget me! Oh! Almighty God,” he said, “you did not lay so much on your son, on your own son, who was God, and I, who am only a poor man, you give ten times more to bear. Oh! death! in pity, death! If you love me, ask God to send me to death!”

For thirteen days and longer!

Oh, Flammarion! have pity on me! In the name of your mother, be merciful! I am mad with grief. It is thirty-two days since he died and I have not slept ten hours since. At night I sit up until four in the morning, and when fatigue has conquered me I throw myself, entirely clothed, on my bed and shut my eyes, but a fixed idea continues during this painful sleep; I do not lose my memories for a single instant, and when I open my eyes I am obsessed by them all day long; what I suffer is so frightful, so atrocious that I ask myself if hell is not preferable to what I endure. Is it possible that it can be God who has created beings destined to experience such horrors!

You, an astronomer and a thinker, who weigh the suns and the worlds, you whose glance penetrates those mysterious regions among which our spirits loses itself, tell me, I beg you on my knees, tell me if our souls survive somewhere. If I can preserve the hope of seeing my son again, if he sees me. If there exists any way of communicating with him.

You who know so many things about the heavens, about spirits, about the marvels of the universe, I ask you in pity to tell me something that can leave my wounded, tortured heart a ray of hope, however feeble! You cannot understand the excess of my grief. I wish that I might die of it. I hope to die, but - my daughter is here, who beseeches me to live, not to leave her alone in the world; and then I see myself forced to live and forced to suffer! What horror! When I think that in an instant I could put an end to my misery! If it were possible to weigh grief, to measure it as you measure the worlds, the weight would be heavy, the extent so great that you would be frightened to think that one human soul could reach such a degree of torture: there must be something infernal in my destiny! Neither red-hot irons nor pincers could cause such suffering! My son, my beloved child! I want him, I wish to see him! I desire no heaven without him. Oh! my adored Emanuel! flesh of my flesh! joy of my life! my happiness as a mother lost forever! Is there a God? is it he who permits these horrors on earth? Monsieur Flammarion, in pity, in the name of those you love and who love you, do not be insensible to the greatest human grief that has ever torn an heart! you who know! We simple mortals can neither know nor understand. Tell me if souls survive somewhere, if they remember, if they still love those who remain on earth; if they see us, if we can call them near us.

Ah! If I could see you and fall at your knees! Forgive this mad act. I no longer know whether I dream or wake! I feel only one thing, a grief so sharp that it seems like a red-hot iron, continually plunged into a gaping wound.

Forgive me, Monsieur Flammarion! Your suns and stars, so beautiful and so marvelous, do not feel or suffer. And I feel a grief greater than all the worlds that move in space! So small, so unimportant a thing, and yet to feel so intolerable a grief! What can it be? What is this mystery? A being so feeble and limited - and to suffer so!

Forgive me once more, Master, in the name of your mother! Forgive me and pity your unhappy countrywoman,

N. Boffard,

At Reinosa, Province of Santander, Spain.

So runs this letter, full of anguish, which I reproduce literally, in order to show all the horror of such a situation. I repeat that I must apologize for the dithyrambic that concern me. Their only significance is in so clearly revealing this immense grief joined to the ardent hope of seeing these clouds dispersed.

One would have to possess a heart of stone to be untouched by these heart-rendering appeals of mother love, to remain deaf to the anguish of such despair, and not to feel an ardent desire to consecrate one’s life to bringing some relief.

Priests receive appeals of this sort every day, because they are considered ministers of God, endowed with the power of penetrating the riddle of the supernatural and solving it. They answer such grief with the consolations of religion. The priest speaks in the name of Faith and Revelation; but faith cannot be imposed, it is not even as generally held as we imagine. I know priests, bishops, and cardinal who are without it, even while they teach it as a social necessity. There are a hundred different religions on earth, all of them perhaps useful, but unacceptable from the point of view of philosophy. Face to face with such events as I have just related, are their ministers able to convince us that a just and good God rules over humanity? The man of science is seated neither on the bench of the confessional nor in the bishop’s chair, and he can tell only what he knows. He is honest, frank, independent, rational before everything. His duty is research and study. We are still seeking and we do not pretend to have found the answer, still less to have a revelation of the truth from heaven. That was the only answer I was able to give the unknown woman, even while I left her the hope of someday seeing her son again in the meantime of remaining in spiritual relationship with him. But I do not, like Auguste Comte, Saint-Simon, or Enfantin, imagine myself the high priest of a new religion. Nevertheless, there can be no doubt that the universal religion of the future will be founded upon science and especially upon astronomy, associated with the knowledge of physics.

Let us make our search humbly and all together. I must excuse myself again for having reproduced the expressions of praise in this letter, but to suppress them would be to suppress at the same time the expression of this distress, this confidence and this hope.

The loss of a son inspired the preceding letter; the loss of a daughter inspired the following.

Theil-sur-Vanne, November, 1899.

Master:

I have the honor of knowing you through your works well enough to be sure that you are kind and to hope that, although I am unknown to you, you will be willing to read with indulgence what I write and will pity my misfortune while according me your spiritual help, of which I have such great need.

On the nineteenth of last September I had the unspeakable sorrow of losing a charming child sixteen and a half years old, of great intelligence and an exquisite delicacy of feeling, and oh! how beautiful! She seemed an incorporeal being, so ideally lovely were her chaste, graceful body and her angelic face. My sweet darling, with her large, magnificent eyes full of expression, framed with lashes as dark as her delicately arched eyebrows, her nose a little long but fine and straight, her mouth somewhat large but expressing much goodness, her face a soft oval, the color of a lovely lily. A dear little dimple in her chin gave beauty to her smile and lighted up a face that was usually rather serious.

A splendid mass of light auburn hair, naturally curly, delicately waved, graced her virginal forehead like a golden foam; her eyes were dear little shells which you divined, hidden in the mass of her fine hair, little nests for kisses, upon which I can no longer place my lips, hungry with tenderness. My dearly loved daughter is no more. My eyes can no longer rest in affection upon her charming, beautiful face; I can only weep for her. So many moral and physical perfections brutally, cruelly, stupidly, savagely blotted out! Pitiless death has taken everything from me. My Renee, my beloved - I have her no longer, and I go on living. Life! - what a prison!

And with her have vanished our good talks. They are ended now - all our wonderful conversations on the most abstruse questions of the life beyond, for although she was young, my daughter was a thoughtful girl, a precious friend, my confidante and dearly loved companion. She was everything to me, this pure and lovely flower, cut down before her full and perfect blooming. Why? What a problem!

Since then, I have thought of suicide as a way of rejoining her, but (did this intuition come from her approaching end?) the evening before her death, while her arms were about me, she said coaxingly, “Mamma must not commit suicide; she must wait, mustn’t she?” I was completely taken aback and I did not understand until the next day when, white as a lily, she gave me her last kiss and closed her eyes forever. Ah! that last kiss! she put all that remained of her life into it. What moments! What tortures! Supreme, never-to-be-forgotten hours! I still see her. I love my suffering. I see my dear little dead girl who had felt, who had guessed my despair: she wished me to remain to weep for her. My revolt against everybody and everything; I find myself murmuring against God Himself, who has taken from me what is a thousand times dearer than my life. from this time on I can live only in the memory of her - my daughter, my constant thought - she was my religion, I adored her. If it is possible, I should like to find some consolation in spiritism, to take refuge in it with faith, hope, and love.

But I know so little about these matters.

My husband and I have tried to experiment with a table, alas! without results, although we did everything to insure success - placing on the table the photograph of our dear child, one of her curls, a page of her writing - and although we evoked her with all the strength of our will. But our tears, our calls, our longings were all useless. I wish to go on, to persevere, and it is toward this end, dear and illustrious Master, with your help, I cannot tell you what this never-failing source of consolation would mean to me. You would mingle in my thoughts with my daughter and God.

Reading your admirable works has made me think of placing my hope in you, feeling sure that you will be able to do as I ask and will be willing to receive kindly the prayer of a poor mother who lives only in the hope of finding once more the child who, as you believe, has vanished but is not dead. Extend your kindness to this sad and ignorant mother. You who have light, lighten her darkness, help her in her moral distress: it is the most beautiful gift of charity that can be given. My greatest desire to fathom these mysteries does not spring from vain curiosity; it is a real, a unique, a potent need from which death alone can deliver me. I await your answer with confidence, but also with impatience, and should you think it wise, I will gladly go to Paris or wherever you advise me.

Be good enough to receive, Monsieur and illustrious scientist, my thanks in anticipation and the warmest greetings of your servant,

R. Primault.

I have reproduced this letter, like the former, 2 without modification, and without suppressing the words of praise addressed to me. As I have already said, the sensations of childish vanity are unknown to me and for more than half a century I have grown used to titles that no longer have any significance for me. The absolute conviction of an astronomer is that we are all atoms of the utmost insignificance. But these expressions of admiration from an author’s readers, whoever he may be, explain the confidence and the faith expressed and should be respected.

Alas! scientific honesty obliges us to say only what we know. We have no right to deceive any one, even from the best of motives and in order to offer him a transitory happiness. I could not give absolute certainty to that poor mother. That was twenty years ago. Since then I have never ceased to search along the same path. This book is written to set forth the elements of a solution.

I have allowed myself to produce literally the touching letter of my unknown correspondent because it expresses the grief of all mothers who have lost a child, of all those who have lost some one dearly loved and whom the very term “Just God” seems an insult to reality. We can easily understand the revolt of these souls. I possess other letters that are incomparably more severe with all the false consolations of religion, that have been sent me by Catholics, Protestants, Jews, spiritualists of all beliefs, free-thinkers, materialists, atheists, taking as a text the injustice which we see about us, in order to deny the existence of an intelligent Principle in the organization of the world. Men often console themselves with skepticism, by submission to the inevitable, by convincing themselves of the indifference of nature to human efforts. Women will not do this, they will not resign themselves. They will not accept nothingness. They feel that there exists something unknown but real, they wish to know.

Hardly a week passes but I receive letters of this sort.

But what is the universal intelligence? We have a tendency to believe that God thinks as we do and that our sense of justice corresponds with His; that His thought is of the same nature as our own, although infinitely superior to it. It is perhaps something entirely different. The insect thinks dully when it forms the chrysalis and also when it bursts this envelop to spread the wings it has acquired; perhaps our thoughts is as far removed from the thought of God as that of the caterpillar is from our own. We are surrounded by mystery.

But our duty is to search.

During the infamous German war, which has cut down, in the flower of their youth, fifteen million young men who had the right to life, who had been brought up by their fathers and their mothers often at a price of enormous sacrifices, letters reached me by the hundred, denouncing the barbarity and injustice of human institutions, lamenting that the hatred of war, which a group of humanity’s friends have preached for so long, should not have been understood by rulers; revolting against God, Who permits such frightful destruction, and declaring that their lives had been shattered by the irreparable loss of those they loved.

More than ever the frightful problem of our destiny rises before us. Is it really insoluble? Cannot the veil be pushed aside, lifted, if only for a moment? Alas! The religions which have all sprung from this heartfelt need, this desire to understand, this grief at seeing before us the mute body of someone dearly loved, have not brought with them the proofs they promised. The finest theological discussions prove nothing. We do not want words but demonstrable facts. Death is the profoundest subject that has ever occupied the thoughts of men, the supreme problem of all times and all peoples. It is the inevitable end toward which we all tend; it is a part of the law of our existence, as important as birth. They are both natural transitions in the general evolution, and yet, for all that, death, which is just as natural as birth, seems to us to be against nature.

Hope in the continuation of life is innate in human nature. It belongs to all periods and all peoples. The development of science plays no part in this universal belief, which rests on personal aspiration and which nevertheless is not based on positive foundations. That is a fact that it is valuable to state.

Sentiment is not a negligible quantity, equal to zero, its scientific coefficient.

The two letters already reproduced from a part of a series that I began to collect long ago and with which my readers are already familiar. The number of letters received, recorded, and included in this collection of documents, of observations, of investigations, of questions that have arisen since the inquiry began, in 1899 (see my work “L’Inconnu et les problemes psychiques,” p. 90), have reached the figure 4106, to which I ought to add about 500 that reached me before I began the inquiry.

I could quote her hundreds of others, very much like the two preceding. Here is one which may seem striking, in another respect, to more than one reader. It is a fervent prayer, which was sent to me at La Rochelle, the fifteenth of August, 1904. it is somewhat brutal, but I give it complete, as I gave the others.

My Elder Brother:

Both my eyes are suffering from cataract, but nevertheless I must write to you. I am a skeptic, a hardened scoffer, but I must believe in something. A frightful, irreparable catastrophe has just crushed the lives of four people. My daughter, whose charm, simplicity and gaiety in 1902 had delighted all Rochefort, beginning with the mothers of those girls who were her rivals, has just gone to a madhouse in Niort, where she vegetates, waiting for the end. It was eighteen months’ agony for her, the martyr, and for her poor mother, who took her to Paris, to Bordeaux, to Saujon, where ambitious specialists demonstrated the utter powerlessness of their pretended science, - an agony also for me, alone here, and for my son, victims of the same catastrophe. I am haunted by the thought of suicide. My brain beats out this refrain: “Your daughter is mad!” and I think of the general misery, of the immense fraud that life is for the great majority of human beings. We carry with us from our birth the defects of our ancestors. What can become of our personality, paralyzed, stuck fast in the carnal magma? This magma, by the play of its molecules, by the example of the parents’ education, by the manner of life forced upon us, by the physical and moral condition of the father and mother, this matrix will be the all-powerful director of the destiny of the personality that has just become incarnate, or rather that has just been merged into an aggregate of which it will be the slave, all its life. what does this all mean?

The gross ignorance and degrading stupidities uttered in the pulpits of the Church have ended by revolting me. But I should like to believe in something acceptable. The spiritualists, with their naive credulity, are really too silly, also. They have given me pages of Pythagoras, Buddha, Abelard, Fenelon, Robespierre which are lacking in common sense. It is grotesque.

For thirty-three years I have not cared to read. The blow that has fallen on me made me pick up some books in which I hoped to find what I seek. In short, here is “L’Inconnu”!

Shall I confess that I have read it religiously? I admit on principle the manifestations and apparitions you mention, as, for example, the story of Marie de Thilo’s cat (page 166). The fear of the cat, which must have seen the phantom, seems to have been due to some electrical excitation. But, Monsieur, my elder brother, why do you see in these dying things only the dying?

There is nothing to prove that the last sigh, the last human thought of the one who is passing should be the cause of manifestations produced without his knowledge. Would it not, on the contrary, be a question of the first step in the world beyond, at the moment of the rupture with the flesh?

I surely belong to the great number of your unknown friends, of those who sympathize with you. They are awaiting, at present, a final book that will conclude your physical investigations. Spirits? Mediums? What have you been able to prove, to verify scientifically, as an astronomer and a mathematician for whom two and two make four and not five? In a word, with your universally recognized authority, what conclusion have you reached? We wish to know. And it is the part of a man such as you to enlighten so many eager minds. And do not think that I am burning incense before you when I speak this way. That is not one of my failings. Are you not going to make up your mind to it? You have no right to conceal anything. Ah! what a service you would render us in writing this honest, convincing book! We have enough of evangelical sermons, of the dissertations of mediums, of neuroses, of claptrap. We beg you, tell us what you know.”

(Letter 1465).

It will be easily understood that I cannot reveal the author of this letter, who is a high official on the Government.

It will also be understood that I should not wish to publish this work until I believed it had attained the dignity of its important subject. It was already under way at the time of this request, in 1904; it had even been begun in 1861, as one can judge from my Memoirs. Such works as these cannot be written out in a year.

Besides, if I had replied to all these appeals I should have written not one book but a dozen. Will they ever see the light? As some of them have been well started for nearly a quarter of a century, they are on the road to being finished.

But let us begin with this one. My readers have assisted me greatly in this research by sending me for many years such observations as helped to prepare the solution; - the solution that has been demanded with perhaps too much confidence. Can our efforts succeed in throwing some light upon this darkness of ages that surrounds the problem of death?

In my childhood, during lessons in philosophy and religious instruction in school, I often heard a discourse, given periodically, which took as text the four words: “Porro unum est necessarium,” or in English, “one single thing is necessary.” This single thing was the salvation of our souls. The lecturer spoke to us of the wars of Alexander, of Caesar, of Napoleon, and arrived at this conclusion: “What does a man profit, if he gain the whole world, and lose his own soul?” they described to us also the flames of hell, and they terrified us with frightful pictures representing the damned, tortured devils in an inextinguishable fire which burned them without consuming them, for all eternity. The subject of the text retains its value, whatever may be one’s beliefs. It cannot be disputed that the one all-important point for us is to know what fate is reserved for us after our last breath. “To be or not to be!” That scene in “Hamlet” is repeated every day. The life of a thinking man is a meditation upon death.

If the existence of human beings leads to nothing, what is all this comedy about?

Whether we face it boldly, or whether we avoid the image of it, Death is the supreme event of Life. To be unwilling to consider it is a bit of childish silliness, as the precipice is before us and as we shall inevitably fall into it someday. To imagine that the problem is insoluble, that we can know nothing about it and shall only be wasting our time if, with daring curiosity, we try to see clearly, - that is an excuse dictated by a careless laziness and an unjustified timidity.

The funeral aspect of death is due, above all, to what surrounds it, to the mourning that accompanies it, to the religious ceremonies that envelop it, to the Dies Irae, to the De Profundis. Who knows if the despair of those who are left behind would not give place to hope if we had the courage to examine this last phase of our earthly life with the same pains that we bring to an astronomical or a psychological observation? Who knows if the prayers of the dying would not give place to the serenity of the rainbow after the storm?

It is hard not to desire an answer to the formidable question that presents itself when we think of our destiny, or when a cruel death has taken from us someone we love. How is it possible not to ask whether or not we shall find each other again, or if the separation is for eternity? Does a Deity or Goodness exist? Do injustice and evil rule over the progress of humanity, with no regard for the feelings that nature has placed in our hearts? And what is this nature itself? Has it a will, and end? Could there be more intelligence, more justice, more goodness, and more inspiration in our infinitesimally small minds than in the great universe? How many questions are associated with the same enigma!

We shall die; nothing is more certain. When the earth on which we live shall have turned only a hundred times more around the sun, not one if us, dear readers, will still be of this world.

Ought we to fear death for ourselves, or for those whom we love?

“Horror of death” is a senseless expression. One of two things is true: either we shall die wholly, or we shall continue to exist beyond the grave. If we die wholly we shall never know anything about it; consequently we shall not feel it. If we continue to exist, the subject is worth examining.

Someday our bodies will cease to live: there is not the least doubt on this point. They will resolve themselves into millions of molecules, which will later he reincorporated in other organisms of plants, animals, and men; the resurrection of the body is an outworn dogma that can no longer be accepted by anyone. If our thought, our psychic entity survives the dissolution of the material organism, we shall have the joy of continuing to live, because our conscious life will continue under another mode of existence that is superior to this. It must be superior, for progress is a law of nature that manifests itself throughout the whole history of the earth, the only planet that we are able to study directly.

As concerns this great problem, we can say with Marcus Aurelius: “What is death? if we consider it in itself, if we separate it from the images with which we have surrounded it, we see that it is only a work of nature. But whoever fears a work of nature is still a child.”

Francis Bacon merely repeated the same thought when he said: “The ceremonies of death are more terrifying than death itself.”

“True philosophy,” wrote the wise Roman emperor, “is to await death with a tranquil heart and see in it only the dissolution of those elements of which each being is composed. That is according to nature, and nothing is evil which conforms to nature.”

But the stoicism of Epictetus, of Marcus Aurelius, of the Arabs, the Muslims, and the Buddhists does not satisfy us: we wish to know.

And besides, whether or not nature ever does anything wrong is a debatable question.

No thinking man can avoid being troubled in his hours of personal reflection by this question: “What will become of me? Shall I die wholly?”

It has been said, not without apparent reason, that this is on our part a matter of naive vanity. We attribute a certain importance to ourselves; we imagine it would be a pity for us to cease to exist; we suppose that God occupies Himself with us, and that we are not a negligible quantity in creation. Assuredly, especially when we speak astronomically, we are no great matter; and even the whole of humanity itself is likewise of little importance. We can no longer reason today as in the time of Pascal; the geocentric and anthropocentric system no longer exists. Lost atoms on another atom, itself lost in the infinite! But at any rate we exist, we think, and ever since men have thought they have asked themselves the same questions to which the most varied religions have attempted to rely, without any of them, however, having succeeded.

The mystery before which we have raised so many altars and so many statues of the gods, is still there, as formidable as in the times of the Chaldeans, the Egyptians, the Greeks, the Romans, and the Christians of the Middle Ages. The anthropomorphic and the anthropophagic gods have crumbled away. Their religions have vanished, but the religion remains - the research into the conditions of immortality. Are we blotted out by death, or shall we continue to exist?

Francis Bacon, more popular and celebrated than Roger Bacon, but without his genius, had, in laying down the foundations of scientific experiment, foreseen the progressive victory of observation and experience, the triumph of fact, judiciously established according to theories, in all the domains of human study except one, that of “divine matters,” of the supernatural,” which he abandoned to religious authority and to Faith. This was an error in which a certain number of learned me still actually persist. There is no valid reason for not studying everything, for not submitting everything to the test of positive analysis, and we shall never know anything that we have not learned. If Theology has been mistaken in pretending that these subjects were reserved for her, Science has been equally mistaken in disdaining them as unworthy or foreign to her mission.

The problem with the immortality of the soul has not yet been solved in the affirmative, but neither has it yet been solved in the negative, as has sometimes been pretended.

It is the general tendency to believe that the solution of the sphinx’s riddle of what lies beyond the grave is out of our reach, and that the human mind has not the power to pierce this mystery. Nevertheless, what subject concerns us more closely, and how can we fail to be interested in our own lot?

The persistent study of this great problem leads us to believe, today, that the mystery of death is less obscure and impenetrable than has been admitted hitherto, and that it may become clear to the mind’s eye by the light of certain actual experiments that were unknown half a century ago.

It ought not to surprise us to find physical research associated with astronomical research. It is the same problem. The physical and moral world are one. Astronomy has always been associated with religion. The errors of that ancient science, which was founded on deceptive appearances, had their inevitable consequences in the erroneous beliefs of former days; the theological heaven must accord with the astronomical heaven under pain of collapse. The duty of all honest men is to seek loyally after truth.

In our epoch of free discussion, science can only study tranquility, with complete independence, the gravest of problems. We can remember, however, - not without some bitterness, - that during the intolerant centuries of the Inquisition, inquiries of free thought brought their disciples to the scaffold. Thousands of men have been burned alive for their opinions: the statue of Giordano Bruno reminds us of this, even in Rome. Can we pass before it or before that of Savonarola in Florence or that of Etienne Dolet in Paris, without feeling a shiver of horror at religious intolerance? And Vanini, burned at Toulouse! And Michael Servetus, burned at Geneva by Calvin!

We once affirmed things of which we were ignorant; we imposed silence upon all seekers. This is what has above all retarded the psychic sciences. Undoubtedly this study is not indispensable to a practical life. Men in general are stupid. Not one out of a hundred of them thinks. They live on the earth without knowing where they are and without having the curiosity even to wonder. They are brutes that eat, drink, enjoy themselves, reproduce their kind, sleep, and are occupied above everything in acquiring money. I have had, during an already long life, the joy of spreading among the different classes of all humanity, in all countries and all languages, the basic ideas of astronomical knowledge, and I am in a position to know the proportion of those who are interested in understanding the world which they inhabit and of forming a rudimentary idea of the marvels of creation. Out of the sixteen hundred million human beings who inhabit our planet there are about a million interested in such things, that is to say, who read astronomical books, out of curiosity or otherwise. As for those who study and make themselves personally familiar with the science, who keep up with the new discoveries by reading special and yearly publications, their number can be placed at about fifty thousand for the entire world, of which six thousand are in France.

We can therefore conclude that out of every sixteen hundred human beings there is one who knows vaguely what world he inhabits, and out of a hundred and sixty thousand there is one really well informed.

As for the instruction in astronomy in primary and secondary schools, in college and lyceums, either civil or ecclesiastical, it virtually amounts to nothing. In the matter of positive psychology the results are equally negligible. Universal ignorance is the law of our mundane humanity, from the days of its simian birth.

The deplorable conditions of life on our planet, the obligation to eat, the necessities of material existence, explain the indifference to philosophy on the part of the earth’s inhabitants, without entirely excusing them; for millions of men and women find the time to indulge in futile amusements, to read newspapers and novels, to play cards, to occupy themselves with the affairs of others, to pass along the old story of the mote and the beam, to criticize and spy upon those about them, to dabble in politics, to fill the churches and the theaters, to support luxurious shops, to overwork the dressmakers and hatmakers, etc.

Universal ignorance is the result of that miserable human individualism that is so self-sufficient. The need of living by the spirit is felt by no one. Men who think are the exception. If these researches lead us to employ our minds better, to find what we are here to do, on this earth, we may be satisfied with this work; for, truly, out life as human beings seems very obscure.

The inhabitant of earth is still so unintelligent and so bestial that everywhere, even up to the present day, it is still might that makes right and upholds it; the leading statesman of each nation is still the Minister of War, and nine tenths of the financial wealth of the peoples is consecrated to periodic international butcheries.

And Death continues to reign over the destinies of humanity!

She is indeed the sovereign. Her scepter has never exercised its controlling power with such ferocious and savage violence as in these last years. By mowing down millions of men on the battlefield she has raised millions of questions to be addressed to Destiny. Let us study it, this final end. It is a subject well worthy of our attention.

The plan of this work is outlined by its aim: to establish the positive proofs of survival. It will contain neither literary dissertations nor fine poetic phrases, nor more or less captivating theories, nor hypotheses, but only the facts of observation, with their logical deductions.

Are we to die wholly? That is the question. What will remain of us? To say, to believe that our immortality rests with our descendants, depends on our works, on the way in which we have helped humanity, is a mere jest. If we die wholly, we shall know nothing of these services we have rendered, and our planet will come to an end and humanity will perish. This everything will be utterly destroyed.

In order to discover if the soul survives the body we must first find out if it exists in itself, independently of the physical organism. We must therefore establish this existence on the scientific basis of definite observation and not on the fine phrases and the ontological arguments with which, up to the present, theologians of all times have been satisfied. And first of all we must take into account the insufficiency of the theories of physiology, as they are generally accepted and conventionally taught.

Chapter 2. Materialism – An Erroneous, Incomplete, And Insufficient Doctrine

We should distrust appearances.

Copernicus.

Every one is familiar with the Positive philosophy of Auguste Comte and his judicious classification of the sciences, descending gradually from the universe of man to astronomy and biology. Every one is also familiar with Littre, the follower of Auguste Comte; his dictionary is on all the libraries and his works are scattered broadcast. I used to know him personally. He was an eminent savant, an encyclopedia, a profound thinker; in addition, a convinced materialist and atheist. The beauty of his face did not correspond to the beauty of his soul. It was difficult to look at him without thinking of our simian origin, and yet he had the greatest nobility of mind and a rare generosity of heart. he lived not very far from the Observatoire. His wife was very pious, and on Sunday he used to escort her to mass at Saint-Sulpice, out of pure and simple goodness, without ever entering the church himself. Le Dantec, atheist and materialist, who succeeded him, let himself be buried with the rites of the church, though this is to be regretted, in order not to pain his wife, who also was very pious, - we should like to see these lifelong companions of the same minds as their husbands. This professor of atheism also was very good. All this is rather paradoxical. The same was true of Jules Soury, that “devourer of cures,” who was buried by them with their liturgies. There is no real logic in this world. But one’s doctrines do not always direct one’s deeds. One can be professing Catholic and yet a liar, or one who takes advantage of others. One can be a materialist and an entirely honest man. I also knew the excellent Ernest Renan, who, out of deep sincerity and in order to absolve himself from all hypocrisy, had refused the priesthood to which his theological studies had led him.

These eminent minds are much to be respected in their sincere opinions, which we should respect as they respected the opinions of others; but we may take exception to their ideas, and moreover they never made any pretense to infallibility.

Littre worked over the psychological questions that we are proposing to study here. We may take his arguments, as well as those of Taine, his emulator, as a basis for the modern materialistic assertions. Do not let us fear to meet them directly and to take the bull by the horns.

In his work entitled “La science au point de vue philosphique,” a chapter on psychic physiology contains the following statements:

Perhaps the expression psychic physiology may appear anomalous. I could have made use of the term psychology, which is used to designate the study of the intellectual and moral faculties. I myself have used this word many times in my writings, and because of its common usage and when the text leaves no room for obscurity in my thought, I shall use it again. It is true that the word (yo%n) which is its root, is suited to metaphysics and theology, but it can also be applied to physiology by giving it the meaning of the totality of the intellectual and moral faculties, - a phrase much too long and complex not to be replaces, on most occasions, by some simpler expression.

Nevertheless, as psychology was undoubtedly at its beginning, and still is, the study of the mind, considered independently of the nervous substance, I neither wish to nor ought to use an expression which is peculiar to a philosophy quite different from that which lends it name to the exact sciences. Among the positive sciences one recognizes no quality without matter, not at all because a priori one has the preconceived idea that there exists no independent spiritual substance, but because, a posteriori, we have never met with gravitation except in a body possessing weight, nor with the heat except in a warm body, nor with chemical affinities without substances that may be combined, nor with life, feeling, or thought except in a living, feeling, thinking being.

It has seemed necessary to me for the word physiology to appear in the title of this work. I could, indeed, have used the expression cerebral physiology. But cerebral physiology implies more than I expect to include.

The brain is engaged in all sorts of operations which I do not pretend to consider, for I shall limit myself to the part it plays in producing those impressions which result in the idea of the exterior world and of myself.

It is for this reason that I have determined to choose the expression, “psychic physiology,” or, more briefly, psychophysiology. Psychic, that is to say relating to feelings and ideas; physiology, that is to say the formation and combination of these feelings and ideas in relation to the construction and function of the brain. This is not because I wish to be so pretentious as to introduce a new expression into science; all that I wish to do here is, on one hand, to outline my subject clearly, and on the other to impress on my readers that the description of psychic phenomena with their connections and relations, belongs to pure psychology and the study of a function and its effects. The more progress psychology has made in breaking away from the theory of innate ideas, especially the psychology that springs from the school of Locke, the more closely it has approached to physiology. And the more physiology has examined the extent of its province the less it has been frightened by the anathemas of psychology, which forbade it to indulge in lofty speculations. And today there is no longer any doubt that intellectual and moral phenomena are phenomena of the nervous tissue, that humanity is only a link, though without a doubt the most considerable link, in a chain that stretches, without any clearly defined breaks, down to the least of the animals; and that, under whatever name we may act, so long as we employ the methods of description, observation, and experience, we are physiologists. I can no longer conceive of a physiology in which all that is best in the theory of feelings and in ideas should not occupy a great place. 3

Such is the basis of the materialistic philosophy of the soul.

I invite the reader to consider scrupulously this manner of reasoning. We may not admit the existence of the soul, “because we know of no quality without matter, because we have never met with gravitation in the body without weight, heat without a warm body, electricity without an electrical body, affinity without substances in combination, life, feeling, thought without a living being, feeling and thinking.”

But this sort of reasoning, starting with the use of the word quality, simply begs the question.

To compare thought to gravitation, to heat, to the mechanical, physical, and chemical reactions of material bodies is to compare two very different things, precisely those things that we are debating, - mind and matter.

The will of a human being, even of a child, is personal and conscious, while gravity, heat, light, and electricity are impersonal and unconscious, the results of certain material conditions, inevitable, blind, and essentially material in themselves. The difference between the two subjects I have mentioned is great; it is all the difference between night and day.

Scientific reasoning itself sometimes errs fundamentally. Heat, for example, does not always come from a warm body; motion, which has no temperature, can produce heat. Heat is a form of motion. Light also is a form of motion. The nature of electricity remains unknown.

I confess that I cannot understand how a man of merit of Littre, the head of the Positivist school, could have been satisfied with such reasoning and not have perceived that this was merely begging the question, almost a play on words; for this argument plays with the word “quality.” What we ought first to prove positively is that thought is a property of the nervous substance, that the unconscious can create the conscious, which is contradictory in principle.

We should hardly dare to compare a piece of wood to a piece of marble or a fragment of metal, and yet we carefully compare the mind and thought, the sentiment of liberty, justice, goodness, the will, to a function of the organic substance. Taine assures us that the brain secretes thought as the liver secretes bile. Does it not seem, with such intellects as his, as if the trend of the argument had been determined in advance, and no less blindly than with the theologians? Is not that a case of preconceived ideas, of systematic convictions?

It is important, from the very beginning of this discussion, for us not to be easily satisfied with words. What is matter? According to general opinion, it is what is perceived by our senses, what can be seen, touched, weighed. Very well! The following pages are to prove that there is in man something besides what can be seen, touched, and weighed; that there exists in the human being an element independent of the material senses, a personal mental principle, which thinks, wills, acts, which manifests itself at a distance, which sees without eyes, hears without ears, discovers the future before it exists, and reveals unknown facts. To suppose that this psychic element - invisible, intangible, and imponderable - is an essential faculty of the brain, is to make a declaration without proof; and it is a self-contradictory form of reasoning, as if one said that salt could produce sugar or that fish could become inhabitants of terra firma. What we wish to show here is that actual observation itself, the observation of the facts of experience, prove that the human being is not only a material body endowed with various essential faculties, but also a psychic body endowed with different faculties from those of the animal organism. And by “actual observation” we mean that we shall use no other method than that of Littre, Taine, Le Dantec, and other professors of materialism, and that we shall repudiate the grotesque doctrines of oral arguments, mere wanderings from the subject.

How was it possible that eminent thinkers such as Comte, Littre, Berthelot were able to imagine that reality is bounded by the circle of our sense impressions, which are so limited and so imperfect? A fish might well believe that nothing exists outside of water; a dog which has made a classification of canine sense impressions would classify them according to odor and not according to sight, as a man would do; a carrier-pigeon would be especially aware of the sense of direction, an ant of the sense of touch in his antennae, etc.

The spirit overrules the body; the atoms do not govern, they are governed. The same reasoning can be applied to the entire universe, to the worlds that gravitate in space, to vegetables and animals. The leaf of the tree is formed, an egg that hatches is formed. This formation, itself, is of the intellect in its nature.

The universal spirit is in everything, it fills the world, and that without the intervention of a brain. It is impossible to analyze the mechanism of the eye and of vision, of the ear and of hearing, without concluding that the organs of sight and hearing have been intellectually constructed. This same conclusion can be drawn, with even more supporting evidence, from the analysis of the fecundation of a plant, an animal, or a human being. The progressive evolution of the fertilized human egg, the role of the placenta, the life of the embryo and the fetus, the creation of the little creature in the womb of the mother, the organic transformation of the woman, the formation of the milk, the birth of the child, its nourishment, the physical and psychical development of the child, are so many irrefutable manifestations of an intelligent, directing force that organizes everything and directs the tiniest molecules with as perfect an order as it does the planets and stars in the immensity of the heavens. And this spirit does not come from a brain. It has been truly said that if God has created man in his own image, man has returned the compliment. If the cockchafers imagined a creator they would make him a great cockchafer. The anthropomorphic God of the Hebrews, the Christians, the Muslims, and the Buddhists has never existed. God the Father, Jehovah, and Jupiter are only symbolic words.

If generation has been admirably arranged from the point of view of physiology, it has been far from perfect from the point of view of maternity. Why so much suffering? Why the frightful final pains? The church sees in them a punishment of Eve’s sin. What nonsense! Did Adam and Eve ever exist? Do not the female animals suffer? Nature takes no heed of the woman’s periods of suffering or of the brutality of the actual birth; it is undoubtedly lacking in sensibility: the “good God” is not tender towards his creature. He is not even humane, and the Sisters of Charity are kinder than he. What a problem! We do not understand God: all the evidence shows this. What does it prove? Our own spiritual inferiority.