7,50 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Muswell Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

The cream of Britain's poets are getting murdered. Victor Priest takes on two assistants to help investigate. In a hilarious and dramatic denoument the criminal is discovered. Priest hires two assistants to help track the criminal. Despite their unconventional and hilarious behaviour they bring the case to a dramatic conclusion.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2012

Ähnliche

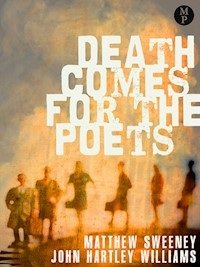

DEATH COMES FOR THE POETS

Matthew Sweeney & John Hartley Williams

To the memory of Ern Malley Liverpool, UK 1918 – Sydney, Australia 1940

Rise from the wrist, O kestrel

I had now met all those who were to make the nineties of the last century tragic in the history of literature, but as yet, we were all seemingly equal whether in talent or luck, and scarce even personalities to one another. I remember saying one night at the Cheshire Cheese when more poets than usual had come: None of us can say who will succeed or even who has or has not talent. The only thing certain about us is that we are too many.

W.B Yeats

Contents

Title Page

Epigraph

Dedication

Chapter 1: The Siege of Lucknow

Chapter 2: The Poetry Wars

Chapter 3: The Submerged Village

Chapter 4: Zum Wohl

Chapter 5: The Drowned Man

Chapter 6: White Vinyl

Chapter 7: The Cheerful Pirate

Chapter 8: The Boot

Chapter 9: A Special Hat

Chapter 10: Klinge, Kleines Frűhlingslied

Chapter 11: A Bolt from the Blue

Chapter 12: The Odic Force

Chapter 13: The Celtic River

Chapter 14: The Wellest Dude

Chapter 15: Cats

Chapter 16: The Dart of Love

Chapter 17: Old School

Chapter 18: Model Trains

Chapter 19: A Spirit Creature

Chapter 20: One, two, three, four…

Chapter 21: BardSlayer!

Chapter 22: The Deep Song

Chapter 23: An Irregular Contributor

Chapter 24: Two Boots

Chapter 25: The Flight of the Scorpion

Chapter 26: Cognac

Copyright

Chapter 1: The Siege of Lucknow

Fergus Diver eased his bulk into an ornate chair and blinked at five-headed and four-armed Shiva in lotus pose on the embossed wallpaper. He had been glad of the anonymous tip-off – the town of Maidstone did not feature on any culinary map he had ever looked at – but the extremely baroque décor made him apprehensive. Shiva was the destroyer as well as the benefactor, was he not? It was a benefactor Diver needed at the moment; the poetry reading he had just given to an audience of about twenty two comatose members of the Kent Marshes Poetry Society had been a clunker. Thank God for this Indian restaurant, its agreeably perfumed air and promise of good food.

And thank God he had managed to dodge the octogenarian chairman of the society, Herbert bloody Ludlow. Diver should have been warned off by the gushing enthusiasm of the man’s voice on the telephone. Why on earth had he agreed to the gig? He had caved in to the man’s boundless, gibbering persistence, that was why.

At the start to the reading, Ludlow had delivered the longest, most rambling and redundant introduction to a guest reader that Diver had ever had. And each of the very few facts mentioned had been wrong. Titles of books scrambled. Prizes awarded that Diver hadn’t won; prizes he had won neglected. Worst of all, the old man kept getting the name wrong, even though he’d been instructed beforehand: ‘Diver pronounced Divver,’ the poet had said with the modest smile he used to convey vital information. Ludlow had kept calling him Fergal Diver, deaf to the poet’s hissed corrections.

Christ, what a way to spend a Sunday evening! The trains had all been fucked up on the way down from London; biblical floods of rain had ruined his second best jacket, and he’d signed only one book afterwards. Many of the members of the Kent Marshes Poetry Society, thought Diver, were well into the territory where they should have been giving serious thought to euthanasia. And they were mean as peasants to boot; the only book he had signed had been a long out of print copy of his second collection, The Tram to Nowhere. He took a deep breath. Was it the four beers he had had at the reading that were making him dizzy, or was it Shiva’s five heads?

Diver tried to blank out the discreet pinging that Indians called music. He allowed the plashing of a fountain at the end of the room to soothe him. A tolerable background, if you had to have noise at all. Not much in Maidstone to satisfy the gourmet, the message had read, but you might find The Siege of Lucknow pleasing. The mystery informant had signed himself: An aficionado of your column.

He rather liked that use of the word ‘aficionado’. Diver’s restaurant column in The Observer brought him more praise and good wishes (and followers) than anything he had ever done in the poetry line. He was used to being approached by diners who had enjoyed places he had written about, and also those who had shared his experiences of gastronomic hell. If there was one thing that united all peoples of the world, it was food – the most universal language of all, more accessible than music, more lyrical than poetry.

Apart from a group of four people at a distant table, he was alone in the restaurant. There were no signs of any staff. He waited. He was beginning to think the waiters had absconded but a sudden yelp and a loud crash from a direction he presumed to be the kitchen reassured him that cookery was in process. A tall Sikh in a turban appeared, handed him a menu, and walked over to the party at the other table. As he studied the menu, Diver became aware of a slight altercation, voices raised. A dispute? He looked up and watched the waiter, who seemed to be putting decorous pressure on the other diners to settle the bill. In no time at all they were being shooed out into the rain, accompanied by much respectful bowing from the Sikh, his hands put together as if in prayer. One of the departing guests said something loud, possibly insulting – a parting shot? Diver took out his notebook and scribbled in it. He always made a point of noticing the behaviour of restaurant staff. The dining experience had many aspects to it; there was a lot more to consider than whether or not one’s steak was perfectly à point. Or one’s rice al dente.

The main restaurant door closed, a heavy curtain fell across it, and the waiter vanished back into the precincts of the kitchen. Diver looked around. He was now completely alone. Why would they chivvy people out of the restaurant when there were so many free tables? Nothing attracted customers more than seeing that places were well patronised. That was what restaurateurs wanted more than anything else; it was a sign of good things. But perhaps a coach party was expected later. Diver looked at his watch. Ten already! Maybe they just wanted to close up.

He opened the opulent menu and began to study it. Diver knew from experience that surprising gastronomic delights were to be found in the most unlikely places and the dishes on offer were far from the usual Indian restaurant fare. Perhaps the evening was going to end well after all; he deserved it. Passing over the starters, he decided to opt for the main course. When the turbaned waiter reappeared, he asked for Murgh Bhogar, Alu Badam Dum, Sagh, pilau rice and a stuffed paratha. “Yes, Sir, the chicken with scrambled eggs, a very good choice, Sir. Smothered potatoes with almonds, excellent. You have picked some of the best things our chef does. Anything to drink, Sir?”

“This 2005 Rioja looks good. Bring me a bottle of that.”

“Yes, Sir.”

In very short time the man had returned with the Rioja, used a proper corkscrew in the professional manner (Diver was pleased to see this in an Indian restaurant), sniffed the cork, poured a finger for Diver to taste and then, on Diver’s nod of approval, half filled the red wine glass and retreated.

The wine was excellent. Diver noted down the price, the year and the name of the producer. Aromas of raspberry and plum, and a hint of mown grass. This was obviously a good place. He settled back in his chair.

They’d started the reading late of course. Why did it always have to be ‘of course’? He’d been liberally supplied with Guinness from the moment he’d walked through the door of the pub and once upstairs in the room designated for the reading he had quaffed a third pint while the venerable chairman hovered at the door as if his entreatingeyes would suck more people into the room. From time to time, Ludlow had glanced back at the visiting poet as if to make sure Diver was not about to metamorphose into a roaring drunk - a possible side effect of readings given to the Kent Marshes Poetry Society?

Diver, surveying the uncrowded room, had noticed that one woman had brought a child of eight years or less. Well, he was not going to delete any expletives on that account. A number of very elderly people were having difficulty finding parking space for their walking sticks and other more cumbersome paraphernalia. Two nuns had stared at him from the end of a row. Had his reputation as one of England’s most famous atheists not reached Maidstone? He had directed an anti-clerical scowl at them and they had smiled and nodded back. He ought to have got up and left then, but of course old troupers keep trouping, the show has to go on, all that rot.

He brooded, staring towards the kitchen. The waiter emerged through waistcoat swing doors, bringing poppadums and pickles, placed them on the table, beamed at Diver and vanished back into the inner precincts.

The poet cracked some slivers and refilled his wine glass. Perhaps it had been a mistake to begin his reading with that poem about the skeleton of a giraffe? It ended with what Diver considered an apocalyptic flourish, possibly a rather too demanding trope for an out-of-town audience, and during the silence afterwards – not so much awe and astonishment, perhaps, as bafflement - he had raked his gaze along the rows of seats as if defying the audience not to applaud. One acne-ridden student-type had indeed started to put his hands together, but stopped when he realised he was alone. That was when Diver’s attention had been caught by the two latecomers. One of them, a tall heavily bearded man, was wearing a deerstalker. The other was von Zitzewitz, the Bavarian-born haikuist.

What was Manfred von Zitzewitz doing at a reading by Fergus Diver? The poet crumbled more poppadum, and chewed thoughtfully. Manfred and he had ceased speaking to each other years ago, after a ferocious argument on a train about the Auden Prize. Diver had won of course. Manfred had been a very bad loser.

The waiter returned and offloaded a tray of sumptuously bubbling pots on to the table, enquired if everything was to Diver’s satisfaction, and went, leaving the poet surrounded by little dishes perched on candle warmers. The poet began to eat with relish, belching between forkfuls, and wishing he had company, anyone at all, with whom he could share appreciation of the excellently prepared food.

Even von Zitzewitz?

No. Diver had drawn a line under that one. He thought back to the reading. There’d been a hum on the mike that had distracted him for a while but the total fiasco had occurred when he had given his new villanelle an outing. After the fourth stanza, with the same two lines repeating in slightly altered contexts down through the poem, he was stopped in his tracks by a piping child’s voice: ‘You’ve said that already.’ Members of the audience had laughed aloud, including von Zitzewitz, who had risen to his feet and with a sardonic nod to Diver quit the room. Yeah, get lost, thought Diver, as he watched him leave. The other latecomer had not even removed his deerstalker, and he was gazing at the poet with a broad smile on his face.

Diver sighed. The Murgh Bogar was a dream. He’d never tasted the dish prepared so brilliantly. The Siege of Lucknow must have engaged a Michelin-starred chef. After such humiliation, what forgiveness? He merited this, didn’t he? Diver emptied and refilled his glass again and recalled how only a week ago an audience of three thousand Columbians had got to their feet and shouted ‘Maestro! Maestro!’ after that same villanelle. Oh to be back at the festival in Medellin, dancing late at night in the tango bar with those sinuous Colombian women.

But this was Maidstone. Utterly Maidstone.

There was always a tipping point when you knew you’d lost your audience, and the villanelle had been it.

At the end of the reading, ignoring the feeble applause and Ludlow’s announcement that Fergal would now be willing to respond to questions, he had made for the door at great speed. The upstairs room of The Spotted Dog in which the reading had taken place was connected to the lounge bar by some twisting, ill-carpeted stairs, and Diver descended these in a rush only to find himself walking towards von Zitzewitz, who was sitting at a far table, grinning in his direction. Turning on his heel, Diver had fetched up by a small bar in the so-called Snug, aware that he was ahead of his audience and would, if he wasn’t careful, end up paying for his own drink. In a state of mortal indecision, he had stood staring at the price list on the wall until a barman had placed a pint glass in front of him, smiled, and vanished. With what gratitude had he downed that Guinness!

He closed his eyes and tried to erase the Kent Marshes Poetry Society from his consciousness by making careful tasting notes in his notebook. Waves of retrospective ignominy halted his pen. He leaned back in his chair, emitting a resonant and prolonged belch. Phew! He was sweating. Looking up from his unhelpful notebook, he observed Shiva’s five heads staring back. Did they all bear a resemblance to von Zitzewitz?

He took a deep breath. A trip into the restaurant’s basement would also have to go into his report. The beers he’d had earlier, together with the wine and the highly spiced food were beginning to create their own karma. What you needed were the suavely-carpeted stairs, the non-kitsch sex-signalling on the lavatory doors, the subdued lighting the big mirrors with their roseate flush, the plentiful soap and hot water, the warm towels…excellent! He felt refreshed as he padded back to his table and found an unasked-for dish of mushrooms, liberally sprinkled with a curious herb, placed on his table mat. He concluded the waiter had seen him making entries in his notebook. This, then, had to be the speciality of the house. He was always gratified to have his connoisseurship appealed to.

He emptied the last drops of Rioja into his glass. The mushrooms were indeed very good, if curiously astringent – a taste he knew he could learn to acquire. He would have to find out from the waiter what the herb was. Somehow or other, he would also have to track down the benefactor who had recommended this place and thank him properly.

“Splendid reading” a Welsh voice had said. “Pity about the audience. What can I get you to drink?” Diver had turned to see the man in the deerstalker behind him.

“Thank you. I’ve just had a Guinness, but I could use another.”

“Did you get my message this morning?”

…………“Message?”

“I’m devoted to your poetry Mr Diver. It’s a real privilege to hear you read.”

“Thank you.”

“But I very much enjoy your restaurant column in The Observer as well. I suppose poets can’t make a living from poetry alone?”

“Indeed, they can’t. So you are my cryptic intelligencer?”

“Guilty,” said the Welshman. “The Siege of Lucknow is truly exceptional for a provincial restaurant. But here comes the audience. I’ll leave you to their tender mercies.”

And then the fellow had gone. Diver had not even learned his name. No doubt Ludlow would know it. The Kent Marshes Poetry Society was obviously a cabal of deviously intimate conspirators who would all know each other’s names. What a piece of luck he’d managed to dodge them at the end. They had actually had the temerity to suggest taking him to the Wimpy bar round the corner.

“Does anyone know The Siege of Lucknow?” he’d asked, downing a beer he had bought himself.

“It’s just down the street,” a lady standing next to him had said-Not wishing to give unforgivable offence, and searching the room for a deerstalker that appeared to have gone, Diver had enquired: “Perhaps some of you would care to join me there?”

“It’s too late for me, Mr Diver,” said Ludlow with an odious chuckle. “We’re really rather modest here as regards our eating habits. A man of your gourmandising sensibilities would probably prefer dining alone anyway.”

Diver had hefted the empty beer glass in his hand, and thought about bringing it down hard on the octogenarian’s bony skull. No, if he could have chosen he would have elected to dine with his Welsh well-wisher. He had thrown a glance across the bar at a known ill-wisher. What had brought von Zitzewitz to his reading, and why was he still sitting there, grinning? Deciding that offence was what he wanted to give after all, Diver had said with venom:

“Actually, I would prefer to eat in discerning company, but if there’s none to be had, I’ll do without.” And he had headed out into the dripping street.

The fountain plopped. The sitar plonked. Diver tried out a few more descriptive arabesques to capture the flavour of the mushrooms. Then, scraping the bowl clean, he sank back in his chair, glugging the last of his Rioja. Another day in the life of a poet. He checked the time, saw it was after eleven, remembered he had put the key for his hotel in a pocket, searched for it in a state of anxiety, and then found it. His room number was 101. He leaned back. He would have liked to have fallen asleep where he was, but suddenly the Sikh waiter was there presenting the bill.

“Was everything OK, Sir?”

Diver tried to express his complete approval but found himself somehow tongue-tied. He struggled to his feet to gain access to his pocket, and in doing so, embarrassed himself by farting. The waiter ignored this, smiling, and when Diver had counted out enough notes to cover the amount plus a generous tip, spun round and vanished back into the kitchen with the little pile of crumpled notes on a silver tray. Diver picked up the receipt left on the table, folded it into his wallet, reclaimed his overcoat, and walked a mite unsteadily out into the night. Behind him he heard the door being bolted.

Which way was it to that damned hotel, and what was it called again? Only a hundred yards or so? More like a hundred miles. As he made his way down the main street he noticed how cold he felt. Stepping off the kerb to cross the road, he nearly lost his balance and fell. Surely he hadn’t drunk that much. A searing pain in his gut left him gasping for air. Christ, maybe it was that chicken with scrambled egg dish. Could it be salmonella? Surely it didn’t act this fast? He stopped and looked up at a flickering sign. The Rudyard Kipling. Yeah. That was it. What a stupid name for a hotel. He crossed the road, realising he couldn’t feel his feet and his hands anymore. This made it extremely difficult for him to locate the key in his pocket. He managed, however, but then the keyhole kept moving around in the door. He stabbed at it, cursing, and finally lurched into the foyer. He dragged himself up the stairs to his first floor room.

Shiva was waiting for him, seated demurely on the edge of the bed. All his heads were smiling, showing terrible, stained teeth, and snakes were uncoiling slowly from five dark throats.

Four arms beckoned him in. At the extremities of each arm were hands as big as shovels, holding knives. The arms elongated and reached caressingly towards him, then slit open Diver’s belly from groin to navel. Shiva was laughing, extricating Diver’s guts, unwinding them and coiling them on the floor.

Diver tried to remonstrate but his vocal cords were suddenly stopped up with some thick, black, bituminous stuff. He turned and staggered away from this monstrosity towards the bathroom, feeling a hand insert itself into his rectum, a whole arm, and then there was Shiva’s hand emerging from Diver’s own mouth, appearing in front of his own eyes, and wagging a ‘naughty boy’ finger at him.

Diver twisted round, impaled like a puppet on this infinitely extensible arm, and sank backwards as he saw a frightful apparition appear in the doorway of the bathroom. The pain was something beyond pain. It was the cosmos exploding. The face no longer looked demure. Not friendly. It was the implacable, dark, frowning face of the destroyer, Shiva, and it murmured his name with the relish of one savouring a victim, Diver, Diver, Diver. Come to me, Fergus Diver.

Chapter 2: The Poetry Wars

Despite heavy traffic on the road from Deal to Lewes, a red Porsche flew past the slowly forward moving column of cars as if there had been no traffic at all. It slipped through gaps most ordinary motorists would barely have considered large enough for a motorbike and flashed onward in the morning sunlight before left-behind drivers had time to be startled. It wasn’t that Victor Priest was late, although he was a bit. He was good at driving fast, and relished doing it.

Two solid lanes of jammed vehicles at the entrance to Lewes obliged him to come to a dead stop. He sat, fretting, his gloved fingers drumming on the steering wheel. Were they all going to the funeral? Hardly likely. Poets didn’t attract large followings, even poets as prominent in the literary world as Fergus Diver. The words of the critic Stanislaus Green, which he’d read that morning in The Daily Telegraph, came back to him: ‘Few poets have ever managed to describe with such forensic acuity the death-haunted human condition.’ Or something like that. It was a fair enough assessment, Priest thought, recalling Diver’s work as the car inched forward. The obituary had sent him to his bookshelf, to the Selected Poems, and he’d turned to the famous piece, ‘The Poisoned’, that imagined a series of violent ends in renaissance Italy. It was a poem he was very familiar with. Surely the Telegraph could have reprinted it, or at least a section of it, for the occasion.

The newspaper had not omitted the details of Diver’s excruciating end. A chambermaid had found him sitting naked and stiff on the toilet. His huge bulk was set in a slouching pose, and his lips were drawn back above his teeth which had bitten through his tongue. He had soiled himself on the bed and there was excrement everywhere.

An undignified exit, thought Priest, for one of Britain’s finest poets.

Eventually, parking the Porsche on Western Road at some distance from St Anne’s Church and striding past the hearse and the mourners’ black Daimler, Priest went up the heavy flagstones of the path and reached the front door of the church. The strains of a recording of Count John McCormick singing ‘Oft in the Stilly Night’ came floating from the interior. Faces turned to study his arrival. He found an empty pew halfway to the front and sat down. There were fewer in the congregation than he’d expected but he recognised a number of eminent poets, including some foreign ones, among them the most recent Nobel Prize-winner for Literature, the Mexican poet Pedro Velasquez. An extremely attractive woman in black stood by his side. McCormick’s lament concluded, and the Orcadian poet Ruarí MacLeod climbed the steps of the pulpit with the aid of a blackthorn stick, placed reading glasses on the end of his nose, peered at his notes, and launched into a eulogy for his dear friend Fergus Diver.

This ended with a reading of Diver’s poem ‘Skua Attack’, then four hefty mourners hoisted the coffin to shoulder height, staggering slightly, before moving forward at a stately pace, with the congregation following, out into the bright sunshine, round two ancient yew trees into the churchyard where a hole awaited. Priest walked at the back of the procession and listened as the last rites were read. As the coffin was lowered into the grave, he watched a bright yellow butterfly follow the coffin down, flutter along its polished length and then rise into the light breeze and veer away. Diver’s soul would not flutter, thought Priest. There had been no lightness about him. The sight and sound of each member of the congregation dropping a handful of earth on to the coffin brought his attention back to the sombre charade in progress. He went forward, added his crumbly contribution, and walked on to where the woman in black was standing on the arm of Pedro Velasquez. She studied him with a smile of puzzlement.

“Please allow me to express my sincerest condolences for your loss, Mrs Diver. I wasn’t invited but I hoped you wouldn’t mind my paying my respects. Victor Priest.”

He took her hand.

“Very good of you to come, Mr Priest. Did you know Fergus well?”

“We corresponded a few years ago, regarding his archive. I’m very aware of his work and his reputation.”

“He had many followers.”

Pedro Velasquez nodded vigorously and put his arm around the widow’s shoulder. She gave the Mexican a half-smile and looked at Priest.

“Are you a poet?”

“A collector, Mrs Diver. I collect and deal in literary manuscripts. But my day job, so to speak, is investigating art crimes.”

“Art crimes?” said Velasquez with a laugh. “We poets are all guilty of those, Seňor. How do you investigate such things?”

“I investigate forgeries and thefts in the art world. But I also handle literary deceptions, plagiarism, unauthorised translation, pirate publication. Artcrimes is the name of my company.”

“Oh,’ said the widow. “Was it you who recovered that stolen Van Eyck? I thought you looked familiar. I saw you on TV in that documentary. It was clever detective work.”

“I merely put two and two together, Mrs Diver.”

“You must come to Mexico,” said Velasquez. “You can put two and two together in my country and still they do not make four.”

“Is that bad? Or good?”

“It is exhilarating, Mr Priest.”

“Perhaps you’d like to join us?” said Mrs Diver. “We’re having a small reception at our house.”

“That’s very kind of you.”

His first impression of a very attractive woman, had now been doubly confirmed by proximity. He also became aware that her composure was being maintained with effort; there was a look in her eyes that suggested anxiety more than grief. He turned to follow her and Velasquez, as the mourners leaving the grave straggled across the grass back towards their cars.

* * *

The narrow street containing the Diver residence was already full of vehicles when Priest got there. He reversed and parked his Porsche some distance away. It began to hail suddenly and he decided to sit where he was till the shower had passed. The hailstones hit the bonnet of the car with such force he expected to see dents appear and yet people were still making their way towards the Diver’s mock-Tudor house. He turned on the radio, catching an item of news to which he listened intently. When the weather forecast began, he switched to Radio 3. Mozart came floating out of the speakers with a counterpoint of drumming hail. He leaned back. What was that accent of hers? It wasn’t German, that was for sure. Thinking of her slender shapeliness and her late husband’s corpulence, he reflected on what an unlikely pairing the Diver marriage had been.

The hailstorm ceased abruptly. He walked through the white gravel on the pavement and entered the open front door of the house. The hallway was crammed with people holding wine glasses in one hand and plates of food in the other. As Priest stood looking round for Mrs Diver, a voice with an Indian intonation asked:

“You’re not a publisher, by any chance?”

“No, I’m not.”

“What a pity! I’m fed up with my publisher and I’m looking for a new one.”

Priest contemplated a small, plump man wearing blue-tinted glasses.

“You must be a writer.”

“I’m a poet. Tambi Kumar. Are you also a maker of verses?”

“Let us say I am an admirer of the late Mr Diver.”

“Yes. What a global talent!”

Priest raised his eyebrows. “Can poetry be global, Mr Kumar? Poems are bound to the language they’re written in, aren’t they?”

“Well, English is global, don’t you think? I divide my time between London and Bombay. Have done for a number of years.”

“I thought it was now called Mumbai?”

“Oh I’m completely traditional. If you ever want to visit I can set up contacts for you. Do you have a card? What is your name?”

“Victor Priest.”

“Not the Victor Priest?”

“That would be too much to expect,” said Priest with a smile.

“What a pity! We need someone to investigate this. The matter of Fergus’s death…Very strange. I’m sure you’ve read the papers.” The Indian lowered his voice and was about to add something conspiratorial when a pretty young woman holding a plate of food joined them. Kumar took in her presence, while at the same time ignoring her, and changed the subject. “Have you been to India, Mr Priest? Do you know Indian poetry?”

“I’m afraid I’m not up to date. Rabindranath Tagore?”

“Oh dear, yes, we’ve moved on since then. I’ll have to bring you up to speed!”

“That’s very kind.” Priest smiled at the young woman. “What’s that you’re eating?”

“Your national dish!” cried Kumar. “Delivery boys were carrying in boxes of the stuff earlier.”

“Pizza?”

Priest gazed at the woman’s plate. The woman looked apologetic. Tambi Kumar giggled, spilling a few drops of wine, then looked down, concerned.,

“How clumsy of me. I hope I didn’t ruin your shoes. Well, as you see, there is wine. Would you like a glass? It’s not as good as the Indian wine I like to drink.”

“I do know a little about Indian wine. Do you drink Château Indage from the Ghats Valley, perhaps?”

“Good heavens, you know it? You’re the first English person I’ve met who’s heard of it.”

“Wine is a passion of mine.”

“A passion? I don’t really associate the English with passion.” This put Kumar into such a fit of giggling that Priest stepped back to avoid the wobbling wineglass.

“Oh Tambi!” said the young woman. A waiter passed carrying a tray and the Indian pounced like a crow on a pizza slice and took a big bite out of it. With his mouth full he asked:

“Are you quite sure you don’t want some? You haven’t even had a glass of wine yet.”

“I’ll go in search of one.”

Priest went in the direction of the wine table, poured himself a glass and looked around again, still hoping to locate Mrs Diver. A babble of sound in the next room attracted his attention. Taking his glass with him, he investigated and came upon an altercation under a birdcage. Raised voices had excited a green parrot whose squawks were alternating with scraps of vehement conversation:

“Writing poetry for children – for God’s sake! – it’s such a waste of intellectual space!”

The parrot screeched.

“The trouble with you, Anita, is that you stick philosophy into your poems without even understanding it!” Another screech echoed the rising tone of indignation with which this was said. Then Tambi Kumar appeared carrying a large white towel which he threw over the birdcage. The two women who were talking stared at the towel as if a dog turd had been flung past their ears and moved away to continue their dispute. The parrot went quiet and Priest appraised the Indian, who turned to him beaming with triumph.

“Very niftily done, Mr Kumar.”

“We Indians know all about parrots. It’s not as easy to silence quarrelling poets, though, is it? I’m afraid there’ll never be an end to these poetry wars!”

“Poetry wars?”

“Were you expecting decorum and civility, Mr Priest? A dignified convocation of poets mourning the departure of one of their own?” Tambi Kumar lowered his voice to a whisper. “Eavesdrop, Mr Priest! I command you to eavesdrop! Many in this room are secretly celebrating the departure of Fergus Diver!”

Priest glanced around. There was a skull on the wall, decorated with small turquoise mosaics. Under it another bad-tempered conversation seemed to be in progress.

“Are they verbal wars, Mr Kumar, or do they ever get physical? The Times considered Fergus Diver’s demise to be a matter of bad restaurant hygiene, nothing more or less, I did hear a report that suggested…well…murder.”

Kumar emitted his squeaky laugh.

“That would be a most unfortunate escalation.”

“Indeed it would. Good parrot husbandry, Mr Kumar. Well done!” Priest moved away, keeping his eye out for the graceful Mrs Diver. His height was an advantage here, and he manoeuvred through the crowd, eavesdropping.

“Horace Venables doesn’t rhyme, Elsbeth, he positively clunks.”

“Did you see von Zitzewitz’s latest haiku in The Independent?”

“Saw it, Laurie. Just didn’t have time to read it all.”

“I’m afraid Gerard-Wright is ineluctably wedded to his ampersands.”

“Oh, Gerard-Wright. Totally dated! He’s still living in the sixties!” Over the top of this a woman’s voice exclaimed:

“Brown only got the award because Krapp was one of the judges!”

* * *

“Mr Priest? Could I have a word in private?” It was Mrs Diver. Something in her tone, he was encouraged to notice, suggested she was not going to talk to him about poetry. He smiled at her.

“That accent, Mrs Diver. Where is it from? I’ve tried but can’t place it.”

“I’ve lived in England many years, Mr Priest. Many people don’t notice. I was brought up in Belgrade.”

“To speak English with a hint of an accent gives our language a gloss. I always notice such things.”

She thought for a moment. “Are you married, Mr Priest?”

“No, why do you ask?”

“Fergus spent a long time trying to improve my accent to the point where I could pass for English. He felt it was his husbandly duty, but I’m afraid he didn’t quite succeed.”

He looked at her and nodded.

“You shouldn’t consider that a failure on your part.”

“I don’t.”

He smiled. “Fergus will be much missed.” Mrs Diver hesitated, then seemed to make up her mind. “Do you ever investigate crimes other than forgeries and thefts, Mr Priest?”

“What kind of crimes?”

“Murder.”

“Murder? I hope you’re not talking about your husband?”

“The police performed an autopsy.”

“That’s usual in an unexpected death of an otherwise healthy person.”

“We don’t know what went on in that restaurant he ate in. I expect you’ve heard that the staff were found tied up and gagged in the kitchen.”

“It was on the radio just now. What did the autopsy reveal?”

“Glyceryl trinitrate, Mr Priest. Do you know what that is?”

“I do. A very explosive poison.”

“They found a massive amount. Please come with me, there’s something I want to show you.”

She led him into the hall, up the stairs and into what clearly had been Diver’s study, went to a desk drawer and took out a photocopy of a letter which she thrust into Priest’s hand. It read:

DIVER

IT WOULD BE FUN TO TORCH THE AUTHOR OF THE ARSONISTS BUT I’VE SOMETHING FUNNIER IN MIND!

Jokerman

The words were composed of uppercase letters cut from newspapers, the signature was in lower case.

“Was your husband not disturbed by this, Mrs Diver?”

“Fergus? No, he laughed it off. Anyone in the public eye, Mr Priest, gets used to being a target for weirdos. He was used to it. The original is with the police, of course.”

“But if they’re involved why are you consulting me?”

“To be honest, Mr Priest, I wasn’t at all impressed by the investigating officer. Besides, the police haven’t done very well lately in solving murders, have they? I remember how you tracked down that stolen painting. Someone with your specialist knowledge of the arts might have an angle on this that would not occur to the police.”

Priest reflected.

“What kind of motive could anyone have for murdering your husband?”

She said nothing. He tapped the letter in his hand.

“I’ve been hearing about the poetry wars. Is it possible that could be more than just a metaphor?”

“The poetry world, Mr Priest, is something of a … of a snake-pit. Jealousy, back-biting. You’d be surprised.”

“Jealousy? An aesthetic motive?”

“Someone has to win the prizes, Mr Priest. My husband did, and a lot of people didn’t. If you see what I mean?”

“I do see what you mean. Tell me about this investigating officer. Why does he not impress you?”

“Dobson is his name, Chief Inspector Dobson. Horrible lecherous man.”

“Lecherous? Has he made advances to you?”

“It’s the way he looks at me. Do you know what I mean, Mr Priest, when I say that some people are just primitive?”

“Murder is a primitive act, Mrs Diver. Perhaps for the solving of such crimes a little primitivism of character is required in a sleuth.”

“It seems to me that you would have more fitting qualities for this case than Inspector Dobson.”

He smiled and she blushed.

“No, no, I mean…I just thought that a man like you…You have the kind of artistic background that would enable you to understand the poetry world. How could a policeman understand that? If you feel you could get involved, Mr Priest, I’d be happy to offer you access to my husband’s archive by way of recompense. You did say you were a dealer?”

“I am. Yes.”

Priest stroked his temple with the palm of his hand.

“Quite frankly,” he said, “I think there is very little that I can do. However…”

He frowned.

“I suppose I could pursue a line of enquiry. I’d be more than happy to take on the task of finding a buyer for your husband’s archive. Naturally, I would not expect any kind of reimbursement…except…”

He studied her face.

“Perhaps the pleasure of meeting you from time to time.”

A flush of colour on high cheekbones accentuated the paleness of her face.

“Thank you,” she said.

He followed her down the stairs, and indicated he would prefer not to return to the reception. She opened the front door for him, and he walked briskly away down the path. Reaching his car, he got in but did not drive away. Instead he took a notebook from the glove compartment and began writing, scoring things out, writing more, then putting a line through what he had written and turning to a new page. He looked up as the first guests began to leave. A shaft of sunlight sliced through a cloud and struck the tinted windscreen, illuminating the left half of his face, leaving the right in shadow. After a while no further guests emerged. He sat quite still for a further ten minutes or so, started the engine, and steered the Porsche through the streets of Lewes.

Chapter 3: The Submerged Village

Daniel Crane alighted from the 68 bus on Waterloo Bridge. A few days of icy weather had made the steps down to the river very slippery, so he took it slowly, holding onto the handrail all the way. A freezing wind came off the Thames and his thin jacket was not at all efficient in deflecting it.

He hurried under the bridge. A blind busker was playing ‘Summertime’ on a mouth organ. Exhaling ghostly breath, Daniel hurried into the warmth of the Festival Hall. He felt in his pocket to see if he had enough money for a coffee. He had – he could even afford a croissant. He took his breakfast to a table by the window.

Croissants always made him think of France. They had to taste even better there. He’d promised himself for a year or more that he’d spend his next birthday in France, picking grapes somewhere south of Avignon. Then, on the proceeds, he’d find a room for a few weeks in Paris. He’d sit in a room overlooking the Seine and write poems. To think that Rimbaud had been only a year younger than Daniel when he’d written Le Bateáu Ivre!

He drained the last of his coffee, brushed the crumbs from his jacket, and headed for the lift. He was here for the Poetry Workshop to be given by the Irish poet, Barnaby Brown. That was still an hour away, but he would make good use of the time in the Poetry Library. He loved the rolling bookcases that could be moved apart from one another by turning a wheel. It had often occurred to him that by spinning the wheel hard an opportunistic assassin could easily crush someone between them. What a way to go – crushed by poetry! He had once asked the librarian what chances there were of getting a job in the library, but the young woman had begun to talk about qualifications and certificates, and he had sighed, thanked her, and left.

When he reached the library door, it was locked. A notice said it wouldn’t open until eleven, which was when the workshop was scheduled to start. What could he do now? He didn’t want another coffee. He prodded at the broken spectacles he had repaired that morning with elastoplast, and stood looking at the notice-board of lost quotations, identifying none as usual. Then he wandered to a chair by the window that looked out onto the river.

How many people had drowned in the Thames, since the city of London had formed around it? And how many of those were suicides? He thought of the American poet John Berryman – that terrible jump into a different river. And Berryman had missed the water. Daniel shivered. The Thames looked cold and grey. It felt appropriate for Barnaby to be giving a workshop on its south bank, as there was so much water in his poems. So much about drowning too.

He remembered the impact the poems had made on him when he’d first encountered them. It had been here, in this building, an event in Poetry International – a joint reading with Fergus Diver. He hadn’t known either poet’s work but Diver’s name was everywhere, and it was this that had drawn him to the reading. Brown had read first. He had walked out onto the platform in a black leather jacket, black cords and a light green shirt. His long black hair tumbled over his collar. He took a sip of water and raised his glance to the back of the hall. Then the audience had become aware of a noise filling the room. It was hard at first to identify what it was. As a muted chorus of seagulls became distinct over the crashing of waves, Brown began, in a powerful Irish voice, to read a poem called ‘To Ash Again’.

The urn turned upside down,

emptied out the ashes

and rolled away. The wind

grabbed each ash flake,

swooped it into the sky,

swirled it across the sea,

over fish, through gulls,

and on the other side

the ashes came together

to form the reborn man

who stole a bicycle,

pedalled up a mountain

and into a rushy tarn

where he drowned,

while the urn floated

across that same sea,

rolled across sand, fields,

then up that mountain, as trout

heaved the corpse out,

lightning bolts blasted it

to ash, which the urn ate,

then turned upside down…

Daniel had shivered. He knew those feelings of death and rebirth. He sat entranced as Brown continued with a poem about attempts to rescue a stranded whale. It was followed by a poem about a ghost U-boat which led to a priest’s love-song for a mermaid. In the background, the gulls whooped. There were poems about wrecks, a tsunami that missed the Aran Islands and the reading concluded with a sequence of haiku about seashells. The seagull cries died down. There was silence followed by great applause.

It had been a terrific performance, and the poems had brought back Daniel’s childhood on the Cornish coast. He had realised that, like Rimbaud, the sea should be in his poems too. The French poet had gone instinctively to the sea for his subject matter, even if – most probably – he hadn’t even seen it when he wrote The Drunken Boat. Why was Daniel working so hard to create a long poem about London? He hated London. He longed to get out.

During the interval, he had admired Barnaby’s most recent collection, and watched a queue form for book-signing. He noticed that everyone had a little exchange of words with the poet. Daniel was envious. What did they have to say? He couldn’t think of anything intelligent enough. He would just stammer. He couldn’t afford to buy the book and it wouldn’t have looked good if he’d presented his library copy of a much earlier collection.

In the second half of the reading he had been unable to concentrate. Fergus Diver, an older man than Barnaby, had the look of an overweight football coach. Before commencing the reading, he had chuckled patronisingly and apologised to the audience for the lack of sound effects in the second half. As he read, he sweated under the lights and had to keep taking his spectacles off to wipe them. Each poem seemed to require a lengthy introduction, about Italian history, Scandinavian folklore, and such like. They didn’t speak to Daniel about the world he lived in: “My final poem,” Diver announced, “will adumbrate the political and environmental implications of rainfall in ways I trust you will find unexpected.”

Daniel had been outraged. Adumbrate! What did that mean? He had sat through the rest of the reading in a fever of detestation.

A Welsh-accented voice broke into his thoughts.

“You wouldn’t happen to be waiting for the poetry workshop, would you?”

“I’m sorry? Oh. Yes, I am, actually.”

He was looking at a man with red hair and a red beard – a big, round-shouldered man.

“Me too. Robert Rees is the name. I’ve come all the way from Aberystwyth for this. Let’s hope it’s good.”

The man pulled up a chair, sat down and held his hand out to Daniel. Was this another of those people who bothered him in the Roundhouse bar? The young man took the proffered hand.

“Daniel Crane.”

“I’m a recidivist workshop-attender. Are you?”

“What?”

“Are you a regular at these events?”

“It’s my first.”

“Oh, you’re a workshop virgin?”

Not just a workshop-virgin, thought Daniel, but he said nothing. The man continued:

“I expect you know the work of Barnaby Brown?”

“Yes, I think it’s brilliant.”

“Good. Good. Where do you come from?”

“St Ives.”

“Wonderful! I edit a magazine called Storm. Coming from St Ives, you’ll know what it’s like to be blown away by one. Perhaps you’d like to send me something?”

Daniel was cautious. People didn’t offer you the chance of publication on a moment’s impulse, did they? Especially if they knew nothing about you. After a moment’s thought, he said: “I could send you a section or two from a long poem.”

“What’s it called?”

“Buried Rivers’. It’s a London poem.”

But Rees was looking the other way. A small group of workshop participants had gathered by the front door of the Voice Box, which was being opened by an attendant.

“I think they’re going in. Shall we join them?”

Daniel was glad he had Robert Rees to sit next to, particularly as all the others in the workshop were women, and there was nobody of his age there. Barnaby came in, smiling. After a warm-up exercise – a surrealist game Barnaby called The Exquisite Corpse, which got everyone laughing – they were given more complex writing challenges, ending with a final, more time-consuming task. They were instructed to wander away to any part of the South Bank Centre in order to complete it. Daniel discovered an unlocked door into the empty Festival Hall and sat in a seat in the very back row, scribbling hard. When an hour had elapsed he rejoined the workshop.

Although he found that the exercise had given him abundant ideas, he felt too shy to share his efforts. He became irritated by his new friend, Rees, whose questions at the end seemed to have little to do with the workshop, and were – or so Daniel thought – too personal, and not relevant.

“Do you teach workshops often, Mr Brown? You do? How interesting? The Tamlyn Trust, yes I’ve heard of them. I suppose these workshops remunerate you very well and help you to polish up your craft?”

Daniel had the feeling Rees was having some kind of joke at Barnaby’s expense. The poet seemed to reach Daniel’s conclusion. He put an end to the proceedings, exhorted them all to carry on writing, and left the room.

Afterwards, the red-haired man accompanied Daniel down the stairs.

“Rather an abrupt departure that. Was I getting on his nerves, d’you think? Perhaps you’ll join me in a glass of wine?”

“I’m afraid I’m skint.”

“No problem. The University of Aberystwyth pays me very well.”

Despite the fact that Rees had revealed himself as an editor who might possibly want to publish something he had written, Daniel was anxious to get away, but the Welshman took his arm and steered him to the bar, where he surveyed the wine list, and looked at Daniel interrogatively.

“They have some quite interesting bottles here. Look. Quite a respectable little Bordeaux. We’ll get a bottle, shall we?”

Daniel was embarrassed at being treated in such an extravagantmanner. What was the man after? Could he be gay after all? They went to a table and sat down. Rees poured two glasses.

“A votre santé.”

“Thankyou.”

“Not bad vino for a snack bar is it? Time they did something about the décor though. It looks like a venue for a provincial beauty contest.”

Daniel hadn’t noticed.

“May I ask what you teach at the university?”

“Well, now…My speciality is Jacobean Tragedy. The purest form of poetry is drama, don’t you think? The core subject of the Jacobeans was death. In whatever guise it comes. This long poem you say you’re working on – how much death is in it?”

Daniel went over in his mind what he had written so far of the poem. There was a scene in which he had described a delivery boy being crushed by a Young’s beer lorry.

“Just one.”

“One? Well, that’s a start,” said Rees with a smile, and drank.

Daniel drank too. He’d actually been thinking of taking that scene out. The bloody corpse in Kentish Town Road, even though he’d witnessed it himself, had felt like an exaggeration.

Barnaby Brown, in earnest conversation with a young woman from the workshop, came round the corner and went to the bar. Daniel remembered how the poet had said during the workshop that the purest form of poetry was the love-poem. Whatever he and the young woman were discussing, it was probably not death. Barnaby had declared he wanted to write more love poems; the world didn’t have enough of them. And he was focussed on the woman in such a way that Daniel could imagine he was already experiencing the gestation of a new love-poem. How confident he looked!

Rees noticed the direction of Daniel’s glance and shook his head.

“A bit of a disappointment, your Barnaby Brown.”

“Why? I thought he was great! “

“All that emphasis on clarity? Likening poetry to film! You can’t write poetry in the 21st century as if language was transparent. The language we use in our daily discourse is full of clichés, stereotypes and commonplaces. It’s up to the poet to transform language.”

Daniel wondered why Rees had bothered to come. The poems that the Welshman had written in the workshop had seemed deliberately goofy. Barnaby had been very good natured about them. And surely the editor of a literary magazine didn’t need to attend a workshop for tyro poets?

Rees refilled both their glasses and set the bottle down with a thump.

“In a sense, the language the poet uses has to die and come back to life.”

“The poet has to die and come back to life?”

Rees nodded.

“Yes, that in a way has to happen too. Look at the way death reinvigorates a poet’s work.”

“What do you mean?”

“Sales. Reputation. Obituaries are great publicity.”

Daniel reflected that in order to have an obituary one had to have a reputation first.

“Doesn’t reinvigorate the poet though, does it?”

Rees roared with laughter.

“Excellent! Excellent!”

Did reputation matter? Rimbaud hadn’t given a toss for it. Daniel watched Rees, who was rummaging in his briefcase. He handed a brochure to Daniel.

“I picked this up earlier. It’s a list of Tamlyn Trust writing courses. Mr Brown will be teaching one quite soon. Did you enjoy today’s workshop?”

“Absolutely.”

“Why not spend a week in Mr Brown’s company doing more writing exercises?”

“A whole week?”

“I fear that is correct.”

“I expect it costs money. Anyway I couldn’t afford the time.”

Rees frowned:

“Why didn’t you read your efforts out, Daniel? Could I see what you did?”

Daniel thought for a minute, then fished in the pocket of his jacket for the two handwritten sheets. He unfolded them and started to read out what he had done. Rees plucked them from his hand and perused them, chuckling.

“A monologue by a hedgehog, what a brilliant idea!”

“Well, I only did what he asked us to do. I picked an animal and tried to imagine what it might say.”

“Why does your hedgehog speak with a Scottish accent?”

“There was a thing in the paper the other day about the culling of hedgehogs on Uist in the Outer Hebrides. They’ve been going round giving them lethal injections. My hedgehog has something to say about that.”

“Indeed he does! A protest poem! Very good! Let me look at the other one.”

Rees studied it. Daniel watched nervously.

“Sex with an alien?”

“I was trying to get that fresh angle he was asking for.”

“Sex and death are very closely related, of course.”

Rees observed the young man with one eye half-closed.

“Do you have sex often?”

Here it comes, thought Daniel.

“No,” he said,

“I’m sure I don’t have to remind you that the French expression for orgasm is petit mort? A little death. The great French poets, of course, Baudelaire in particular…”

No, he was wrong. Rees was an academic after all. Daniel stopped listening and watched Barnaby leave the bar with the young woman. Despite the wine, which was beginning to make him feel fuzzy, he felt suddenly disenchanted by everything. He would never get a woman. Rees’s monologue on French poetry was boring, his praises didn’t ring true and if he was after something else, Daniel wasn’t going to provide it. He wanted to escape back to Kentish Town, to his bedsit. When Rees offered to replenish his glass with the last of the wine Daniel refused politely, made his excuses and left.

He took the bus home, lay down on his bed and slept.

Waking up later that evening, groggy and hungry, he took his emergency ten pound note from under the alabaster duck his grandmother had given him and went to the chippie on Prince of Wales Road. He took back with him rock salmon and a large chips, then ate them out of the paper, which he spread on a chair. He’d slung his binoculars round his neck so he could keep an eye on the girl across the street. It was about her bedtime, and he had been lucky enough once or twice to catch her undressing. She wasn’t too bothered about drawing the curtains. Seeing that nothing was happening, he went back to his fish and chips, and looked again at the poems he’d written that morning. Even if Rees hadn’t been sincere in his compliments, he would submit the poems to Storm anyway.

Having eaten, he took off the binoculars, and went to the nearby internet café. He could find no mention of Storm magazine. Then he went on to the Aberystwyth University website but could find no mention of any Robert Rees under the staff listings. That was strange. He pondered this for a bit, then went home and keyed in the two new pieces, making small improvements as he did so, and finding titles for them: ‘Bristles’ and ‘Thwuqq’.

They went well together, he thought. He plugged in his printer to the laptop he had built himself from cheap components and printed the poems out. He put them in an envelope and addressed it to Robert Rees, editor, Storm magazine, English Department, University of Aberystwyth, Wales. He would post it the following day.

He aimed his binoculars back at the window. She was undressing. He grabbed his sketch book and began to draw her. Yes! He went to bed happy.

* * *