1,82 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: Delphi Classics

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Serie: Delphi Poets Series

- Sprache: Englisch

- Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

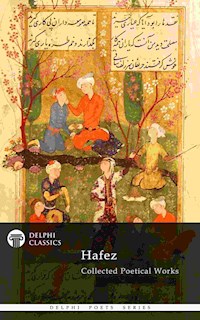

The collected works of Hafez, the fourteenth century poet of Shiraz, are regarded as a pinnacle of Persian literature. The extraordinary popularity of Ḥafeẓ’ poetry in all Persian-speaking lands stems from his concise, often colloquial, yet musical language, free from artificial virtuosity. The Delphi Poets Series offers readers the works of the world’s finest poets, with superior formatting. This volume presents Hafez’ collected poetical works, with numerous translations, beautiful illustrations and the usual Delphi bonus material. (Version 1)

* Beautifully illustrated with images relating to Hafez’ life and works

* Concise introduction to Hafez’ life and poetry

* Images of how the poetry books were first printed, giving your eReader a taste of the original texts

* Excellent formatting of the poems

* Easily locate the poems you want to read

* Includes four different translations of Hafez’ poetry - John Haddon Hindley, Herman Bicknell, Gertrude Lowthian Bell and Elizabeth Bridges

* Features a bonus biography - explore Hafez’ mystical life

* Scholarly ordering of texts into chronological order and literary genres

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to see our wide range of poet titles

CONTENTS:

The Life and Poetry of Hafez

BRIEF INTRODUCTION: Hafez

PERSIAN LYRICS

THE DIVAN

POEMS FROM THE DIVAN OF HAFIZ

SONNETS FROM Hafez AND OTHER VERSES

The Biography

INTRODUCTION TO Hafez by Getrude Lowthian Bell

Please visit www.delphiclassics.com to browse through our range of poetry titles or buy the entire Delphi Poets Series as a Super Set

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 306

Ähnliche

Hafez

(1325/26–1389/90)

Contents

The Life and Poetry of Hafez

BRIEF INTRODUCTION: HAFEZ

PERSIAN LYRICS

THE DIVAN

POEMS FROM THE DIVAN OF HAFIZ

SONNETS FROM HAFEZ AND OTHER VERSES

The Biography

INTRODUCTION TO HAFEZ by Getrude Lowthian Bell

The Delphi Classics Catalogue

© Delphi Classics 2017

Version 1

Hafez

By Delphi Classics, 2017

COPYRIGHT

Hafez - Delphi Poets Series

First published in the United Kingdom in 2017 by Delphi Classics.

© Delphi Classics, 2017.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form other than that in which it is published.

ISBN: 978 1 78656 210 4

Delphi Classics

is an imprint of

Delphi Publishing Ltd

Hastings, East Sussex

United Kingdom

Contact: [email protected]

www.delphiclassics.com

NOTE

When reading poetry on an eReader, it is advisable to use a small font size and landscape mode, which will allow the lines of poetry to display correctly.

The Life and Poetry of Hafez

Shiraz, the sixth most populous city of Iran and one of the oldest cities of ancient Persia — Hafez’ birthplace

Shiraz in 1681

BRIEF INTRODUCTION: HAFEZ

Khwāja Shams-ud-Dīn Muḥammad Ḥāfeẓ-e Shīrāzī, known by his pen name ‘Hafez’, was born in Shiraz, Iran, in c. 1315 and his parents were from Kazerun, Fars Province. Despite his profound effect on Persian life and culture and his enduring popularity and influence, few details of his life have survived. Accounts of his early life rely upon traditional early biographical sketches, which are generally considered unreliable. From an early age, he memorised the Quran and was given the title of Hafez, which he later used as his pen name. The preface of his Divān, an ancient collection of his poems, in which his early life is discussed, was written by an unknown contemporary whose name may have been Moḥammad Golandām.

Hafez was supported by patronage from several successive local regimes; firstly by Shah Abu Ishaq, who came to power while Hafez was in his teens; then Timur at the end of his life. Though his work flourished mostly during the twenty-seven-year rule of Jalal ud-Din Shah Shuja, it is claimed that Hafez briefly fell out of favour with the ruler for mocking inferior poets. Shah Shuja wrote poetry himself and may have taken the comments personally, forcing Hafez to flee from Shiraz, though no tangible historical evidence can support this.

Many semi-miraculous mythical tales were woven around Hafez after his death. According to one tradition, before meeting his patron Hajji Zayn al-Attar, Hafez had been working in a bakery, delivering bread to a wealthy quarter of the town. This was when he first saw Shakh-e Nabat, a woman of great beauty, to whom some of his most celebrated love poems are addressed. Captivated by her beauty, but knowing that his love for her would not be requited, he allegedly held his first mystic vigil in his desire to realise the union. Then he encountered a being of surpassing beauty that identified himself as an angel and his further attempts at union became mystic — a pursuit of spiritual union with the divine. The Western literary parallel of Dante and Beatrice would serve as a good example.

At the age of sixty, Hafez is said to have begun a Chilla-nashini, a forty-day-and-night vigil, conducted by sitting in a circle he had drawn for himself on the ground. On the fortieth day, he once again met with Zayn al-Attar on what is known to be their fortieth anniversary and was offered a cup of wine.

Hafez was acclaimed throughout the Islamic world during his lifetime, with other Persian poets imitating his work, and he received many offers of patronage from as far as Baghdad to India. His poetry was first translated into English in 1771 by William Jones. The verses would make a lasting impression on such Western writers as Thoreau, Goethe and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Hafez is best known for his poems that can be described as “antinomian” and with the medieval use of the term “theosophical”, indicating mystical work by authors inspired by holy books. He wrote primarily in the literary genre of lyric poetry that is the ideal style for expressing the ecstasy of divine inspiration in the mystical form of love poems. His poems are composed in the literary form of the ghazal, comprising rhyming couplets and a refrain, each line sharing the same metre. A ghazal may be understood as a poetic expression of both the pain of loss or separation and the beauty of love in spite of that pain. The form originates in Arabic poetry long before the birth of Islam. It is derived from the Arabian panegyric qasida. The structural requirements of the ghazal are similar in stringency to those of the Petrarchan sonnet. In style and content, it is a genre that has proved capable of an extraordinary variety of expression around its central themes of love and separation.

Themes of Hafez’ ghazals include the beloved, faith and exposing hypocrisy. They often deal with love, wine and scenes in the tavern, all presenting ecstasy and freedom from restraint, whether in actual worldly release or in the voice of the lover speaking of divine love. His influence on the lives of Persian speakers is immense and his poems continue to be employed in Persian traditional music, visual art and calligraphy.

Hafez manuscript of the Divan, 1584

Divan of Hafez, Persian miniature, 1585

A collection of ghazals with illuminated headpiece, University of Pennsylvania

Doublures inside a nineteenth century copy of the Divān of Hafez. The front doublure shows Hafez offering his work to a patron.

PERSIAN LYRICS

OR, SCATTERED POEMS FROM THE DIWAN OF HAFIZ

Translated by John Haddon Hindley, 1800

CONTENTS

PARAPHRASES IN VERSE.

GAZEL I.

GAZEL II.

GAZEL III.

GAZEL IV.

GAZEL V.

GAZEL VI.

GAZEL VII.

GAZEL VIII.

GAZEL IX.

GAZEL X.

GAZEL XI.

PARAPHRASES IN PROSE.

GAZEL I.

GAZEL II.

GAZEL III.

GAZEL IV.

GAZEL V.

GAZEL VI.

GAZEL VII.

GAZEL VIII.

GAZEL IX.

GAZEL X.

GAZEL XI.

APPENDIX.

ADVERTISEMENT.

SUPPLEMENT.

VARIOUS READINGS OF THESE GAZELS FROM FOUR MANUSCRIPTS OF THE DIWAN-I-HAFIZ.

PARAPHRASES IN VERSE.

NUNC et ACHÆMENIO

Perfundi nardo IUVAT, et fide CylleneaLevare diris pectora solicitudinibus.

HORAT. Ep xiii. 8.

GAZEL I.

THIS little poem bears strong allusion to the metaphysical theology of the Musselmans. According to the mystical vocabularies on HAFIZ, by wine (mentioned hereafter in one of these stanzas periphrastically as a flaming ruby), the poet invariably means devotion, and, either from contemplating the beauties of nature at sun-rise, or from having been awakened from sleep (there explained to be meditation on the divine perfections), by the fays of the solar light he may here be supposed to be calling on the religious around him to assist in adoring the great Creator. By the breeze, these interpreters say, is meant an illapse of grace; by perfume, the hope of the divine favour; by the tavern or banquet-house, a retired oratory; by its keeper, a sage instructor; by beauty, the perfection of the Supreme Being; and by wantonness, mirth, and ebriety, religious ardour, and disregard of all terrestrial thoughts and objects. (Asiatic Res ii. 02, iii. 170). This Gazel, therefore, may be conceived to open with the poet’s impatience not to lose a moment from elevated abstraction on the Deity, and with his invitation to those who are filled with divine love, to regale themselves and imbibe wine or the devotional spirit, and to those who thirst after wisdom, to offer their vows to Heaven and to give themselves up to the religious enjoyments of celestial and angelical love.

It may be here observed, that, deeply versed as our author appears to have been in these mysterious tenets, he is also recorded to have given public lectures on Muhammadan Theology and Jurisprudence, and even to have composed a commentary on the abstruse and doubtful passages of the Koran. Some of his fragments, or marginal notes, are said to be yet extant. It may be remarked also in this place, that from various passages in his poems, he seems to have indulged a great partiality for a secluded and monastic life. Reviski, indeed, supposes him to have been the senior or prefect of some monastery (monasterii alicukus senior vel praecfectus), though he owns he can produce no positive proof of this (Hoc non ausus sim fidenter asserere). Prooem xxi.

It is not perhaps improbable that this may be also descriptive of the morning worship of the Persians in adoration of the sun and its vernal effects upon the vegetable creation. We are informed from good authority, that the ancient Persians worshipped three times each day; most likely, when the sun was rising above,. and sinking beneath the horizon, and at its meridian.

PARAPHRASE.

In roses veil’d the morn displaysHer charms, and blushes as we gaze;Come, wine, my gay companions, pourObservant of the morning hour.

See, spangling dew-drops trickling chace,Adown the tulip’s vermeil face;Then come, your thirst with wine allay,Attentive to the dawn of day.

Fresh from the garden scents exhaleAs sweet as Edens fragrant gale:Then come, let wine incessant flowObedient to our morning vow.

While now beneath the bow’r full-blownThe rose displays her em’rald throne,Let wine, like rubies sparkling, gleamRefulgent as morns orient beam.

Come, youths, perform the task assign’d:What! in the banquet-house confin’d?Unlock the door; why this delay.Forgetful of the dawn of day?

Shall guests at this glad season wait?Come, keeper, open quick the gate:’Tis strange to let time pass away.Regardless of the dawn of day.

Ye love-sick youths, come, drain the bowl:Thirst ye for wisdom? feast the soul;To heaven your morning homage payWith hearts that glow like dawn of day.

Kisses more sweet than luscious wine.Like HAFIZ, sip from cheeks divine,‘Mid smiles as heav’nly Peries bright,And looks that pierce like orient light.

GAZEL II.

IN the following lines the poet calls upon his countrymen to join him in celebrating the Nuruz or vernal season, and alludes to that most favourite fable of Eastern poetry, the Loves of the Rose and the Nightingales. The fondness manifested by the bird to the flower, particularly set its first appearance, seems to have given rise to this elegant allegory, the beauty of which, being founded upon local circumstances and local scenery, cannot certainly in the same manner impress the mind of an who has not, like the Asiatic, been accustomed to witness the curious and interesting feet. The candid reader of these poems will prepare himself to make due allowance for the striking difference of Asiatic manners and opinions, and recollect, that many things which may startle him, were not only countenanced by custom, but sanctioned by religion. The concluding stanza alludes to the prostrate mode of salutation among the Asiatics, touching the dust of the ground with their forehead. Our countryman Herbert, in his account of the diversions at this season, says, that, “at the Nuruz, or spring, they send vests to each other: — then also the gardens are opened for all to walk in. The women likewise, for fourteen days, have liberty to appear in public, and, when loose, like birds enfranchised, lose themselves in a labyrinth of wanton sports. The men also, some riding, some sitting, some walking, are all in one tune, drinking, singing, playing, till the bottles prove empty, songs be spent,” &c. “In my life, I never saw people more jocund, nor less quarrelsome.” — Herbert’s Travels, p. 130.

PARAPHRASE.

Hither bring the wine, boy! hither bring the wine, boy!For the season approaches, the season of joy.Let us frolic and revel ‘midst gardens and bowers.Since the roses now bud, and the season is ours.Let the vows of repentance religion has made,Be forgotten, and broken beneath the cool shade:Let us warble, like nightingales, through the gay grove,And, imbedded in roses, here nestle in love.Come, replenish, replenish the goblet with wine,For of happiness lo! the sweet rose is the sign:While she ripens and blows, your enjoyments pursue,For anon she will wither and bid us adieu.To the shade then where roses embowering twine,Come, repair, quick repair, with thy friend, and with wine;Let oblivious enjoyment there banish distress,Whilst we warble, like nightingales, ‘midst the recess.’Tis from HAFIZ the rose claims her tribute of praise,Let him prostrate before her his soul in soft lays,Let him bow down his head to the dust at her shrine,And in strains like the nightingale’s hail her divine.

ANOTHER, MORE FREE.

Beds of flow’rs of gayest hueBeckon us to joy anew:Bring the heart-inspiring wine,Let the soul its cares resign;Lo! the vernal zephyr blows,Scented with the blooming rose.

Borne on pleasure’s new-fledg’d wing,Loud, like nightingales, now sing‘Mid the cool sequester’d shade,Nestling in sweet flow’r-beds laid:There, like them, with love repose,Chanting to the blooming rose.

In the mirth-enliven’d bowerWine, convivial songsters, pour:See the garden’s flow’ry guestComes in happiness full-drest,Round us joy’s perfum’ry throws,Offspring of the blooming rose.

Hail! sweet flow’r, thy blossom spread,Here thy welcome fragrance shed;Let us with our friends be gay,Mindful of thy transient stay:Pass the goblet round; who knowsWhen we lose the blooming rose?

HAFIZ loves, like Philomel,With the darling rose to dwell:Let his heart a grateful layTo her guardian humbly pay,Let his life with homage close,To the guardian of the rose.

GAZEL III.

THE polished Anacreon of Iran now addresses the minstrel or musician. The mirthful and amorous playfulness of this Gazel, is highly characteristic of the gaiety of Asiatic manners, and must be powerfully insinuating to the convivial and voluptuous Persian.

The learned reader will immediately perceive, that the concluding burthen of every stanza totally baffles all attempts at minuteness of version, and may serve to shew the richness of a dialect which can so elegantly adapt the same simple expression to so many varied meanings. He will also notice, that the last stanza is perhaps more dilated than the original will altogether fully authorize; but, we trust, the annexed Paraphrases in Prose, will compensate, in some degree, for these and similar liberties.

PARAPHRASE.

Minstrel, tune some novel lay,Ever jocund, ever gay;Call for heart-expanding wine,Ever sparkling, ever fine.

Sit remov’d from prying eyes;Love the game, the fair thy prize;Toying snatch the furtive bliss.Eager look, and eager kiss;Fresh and fresh repeat the freak.Often give, and often take.

Canst thou feed the hung’ring soulWithout drinking of the bowl?Pour out wine; to her ’tis due:Love commands thee — Fill anew;Drink her health, repeat her name,Often, often do the same.

Frantic love more frantic grows,Love admits of no repose:Haste, thou youth with silver feet,Haste, the goblet bring, be fleet;Fill again the luscious cup,Fresh and fresh, come, fill it up.

See, you angel of my heartForms for me, with witching art,Ornaments of varied taste,Fresh and graceful, fresh and chaste.Gentle Zephyr, should’st thou roam,By my lovely charmer’s home,Whisper to my dearest dear,Whisper, whisper in her ear,Tales of HAFIZ; which repeat,Whisper’d soft, and whisper’d sweet;Whisper tales of love anew,Whisper’d whisphers oft renew.

GAZEL IV.

THIS Gazel opens with the artless effusion of an extravagant Amoroso. Fancy pictures to him his mistress passing, as it were, in review before him; and Affection seizes the gratifying moment to turn even defects into charms, and to consider the very minutest thing appertaining to her as invaluable: Nay, he goes so far as to declare, that he would barter away even the renowned Bokhara and Samarcand, the capital cities of and Taimur, were they his, for the mere mole on the cheek of his lovely fair one. His favourite and native Shiraz, its cooling fountains and its rosy bowers, the gay and sprightly damsels that sport within and around it, characterised by the poet’s most choice and glowing epithets, who have plundered him of his peace of mind, and whom he compares to Janissaries rushing upon their predatory banquet, seem all to involve him in the happiest of reveries. Yet his powers of praise still fail him. Charms, so all-perfect as these, are too exquisite, too superlative to be described. His love, again, is defective, incomplete, and requires to be ratified by possession. It were just as probable to hope to improve, the finest natural complexion by cosmetics, or the meretricious embellishments of art, as to attempt to heighten such consummate beauty by any thing so feeble as verbal delineation. A change in the tide of his thoughts, therefore, becomes necessary. Accordingly, Epicurean-like, he calls for the minstrel to divert, and for wine to drown his perplexities. He ridicules the casuistry and prophetical folly of prying into the events of futurity, and pronounces it a search always abstruse, presumptuous, and fruitless. Yet all this cannot turn aside the current of his passion: it rather tends to aggravate, than to relieve it; and, by reminding him of a chapter in the Koran, (Joseph, c. 12), brings Zuleikha’s case to his recollection, and hints to him, that there did once exist a love, which even overpowered all virtuous considerations. He once more, therefore, cherishes his passion. The beloved object is pathetically conjured by him to attend to the counsels of prudence; to bear in mind, that, in spite of all the suggestions of malice, he still loves her: that he petitions Heaven to preserve her; and that, if she reflects only for a moment on the suavity of her own innate disposition, every expression of malevolence must appear to her unnatural, unbecoming, and detractive from her beauty, as much so as it would be to attribute to her the poison of the scorpion. This thought he seems to prize as sufficiently dazzling to constitute the concluding bead of this melodious string of pearls; and, calling upon himself, in the triumphant pride and rapture of the moment, to sing this Gazel sweetly, the elated and self-applauding bard boasts of his composition as a paragon of harmonious brilliancy, studded and bespangled with poetical beauties, outshining even the Pleiades among the stars of Heaven.

PARAPHRASE.

1. Fair maid of Shiraz, would’st thou takeMy heart, and love it for my sake,For that dark mole my thoughts now traceOn that sweet cheek of that sweet face,I would Bokhara, as I live,And Samarcand too, freely give.

2. Empty the flagon, fill the bowl,With wine to rapture wake the soul:For, Edens self, however fair,Has nought to boast that can compareWith thy blest banks, O Rocnabad!In their enchanting scen’ry clad;Nor ought in foliage half so gayAs are the bow’rs of Mosellay.

3. Insidious girls with syren eye,Whose wanton wiles the soul decoy,By whose bewitching charms beguil’dOur love-smit town is all run wild,My stoic heart ye steal awayAs Janissaries do their prey!

4. But, ah! no lauréat lovers’ praiseThe lustre of those charms can raise:For, vain are all the tricks of art,Which would to nature ought impart;To tints, that angelize the face,Can borrow’d colours add new grace?Can a fair cheek become more fairBy artificial moles form’d there?Or, can a neck of mould divineBy perfum’d tresses heighten’d shine?

5. Be wine and music, then, our theme;Let wizards of the future dream,Which unsolv’d riddle puzzles still,And ever did, and ever will.

6. By Joseph’s growing beauty mov’d,Zuleikha look’d, and sigh’d, and lov’d,‘Till headstrong passion shame defy’d,And virtue’s veil was thrown aside.

7. Be thine, my fair, by counsel led,At wisdom’s shrine to bow thy head;For, lovely maids more lovely shineWhose hearts to sage advice incline,Who than their souls more valued prizeThe hoary maxims of the wise.

8. But, tell me, Charmer, tell me whySuch cruel words my ears annoy:Say, is it pleasure to give pain?Can sland’rous gall thy mouth profane?Forbid it, Heav’n! it cannot be!Nought that offends can come from thee:For, how can scorpion venom dripFrom that sweet ruby-colour’d lip,Which, with good nature overspread,Can nought but dulcet language shed?

9. THY Gazel-forming pearls are strung,Come, sweetly, HAFIZ, be they sung:For, Heav’n show’rs down upon thy laysThoughts, which in star-like clusters blaze.

GAZEL V.

NOT Petrarch himself could approach his favourite Laura with a more extravagant and circumstantial address than this of the idolatrous lover, HAFIZ. He represents his mistress as one of the Temple Idols, loaded with trinkets and brilliant ornaments, and himself under the character of her votary or worshipper, but not without glancing, in the outset, at his past experience of her hard-hearted disposition. He afterwards goes on, painting her as a celestial being kindling his passion into the most flaming and enthusiastic adoration of her personal attributes; and (perhaps in allusion to the peplus or highly-decorated tapestry with which the images are commonly adorned on the great festivals) he wishes himself within the sphere of the fancied nimbus or glory of his belle Idol; or, more directly to meet his idea, equally in possession of her charms with such an embracing veil. Pursuing the same emblematical similitude, he declares his reason and his religion to be lost and absorbed in the divine contemplation of the angelical charms of his Idol; and observes, that no-thing can cure the frailty and infirmity of his love-sick soul, but the gracious aid of her celestial, of her healing love, and compassionate indulgence.

PARAPHRASE.

That Idol with ear-drops so bright,And whose heart is obdurate as stone,Of reason has robb’d me outright,Of myself: for, her captive I’m grown.

No thought the keen glance can pourtray,Or the mien of my Idol so fair,No angel such charms can display,She’s an Idol beyond all compare.

Her company breathes soft delight;Neatly veil’d in a robe she is drest:The moon cannot shine half so bright;Love his altar has plac’d in her breast.

Her passion my soul sets on fire,Thro’ my heart I now feel the flame move,I boil, I boil o’er with desire,I am all in a ferment of love.

Oh! were she but clasp’d in these arms!Oh! how happy would then be my case!No vest, that infolds her rude charms,Could enjoy, like my heart, the embrace.

Let death close my eyes when it may,O’er my love she shall still bear controul;My body may moulder away,Yet she’ll ne’er be forgot by my soul.

Her bosom and shoulders I view — Yes — again, and again, and again:My reason then bids me adieu,My religion grows fruitless and vain.

Religion! — O HAFIZ! how vain!For thy cure from her mouth thou must sip;A kiss must relieve thee from pain,A sweet kiss from her honey-stor’d lip.

GAZEL VI.

THE sprightly turn of the interrogatory at the conclusion of each distich, contitutes the leading peculiarity of this Gazel, which (for a reason similar to that assigned in Gazel III.), we can hardly hope to imitate with any degree of literal nicety. The poet appears to have quarrelled with the object of his passion; and there seems to have been some interruption to the connection, or at least considerable coolness betwixt them. He apparently offers these effusions as a tributary overture at reconciliaton: and, though he does not stoop to make too great advances, by unbosoming himself over-freely, yet nature speaks, through the veil which his art has thrown over it, sufficiently to shew the full amount of his feelings. He confesses that he has felt the painful anxietude of Love, yet he declines to give a minute description of it: though he owns that his hours have been empoisoned by the effects of absence, yet he is averse to enter into a detail of their influence upon him: even the name of his mistress, the recollection of moments of melting tenderness, soft endearments, goading reproaches, and the afflictive pangs of absence, are circumstances which, however pleasant or painful, seem only to be brought forward in order to evince that they have merely a negative claim to his attention. He, however, sums up his feelings in one word, by declaring that his love has arrived at that pitch of anxiety which it is in vain to ask him to describe.

PARAPHRASE.

Tho’ I have felt a lover’s woes,These ask me not to state:Tho’ absence poisons my repose,This bid me not relate.

Far, far I search’d the world aroundFor her I love so well.My charmer’s name’s a magic sound,Which ask me not to tell.

My eyes her lovely footsteps trace,My tears the track bedew;Ask not the secret of my case,To whom these tears are due.

No longer since than yesternight,I heard her tongue declaim,In accents which, in love’s despite,Oh! ask me not to name.

Why bite that lip? Why hints suggest,As if I could betray?A rubied lip, ’tis true, I’ve prest;But whose — don’t bid me say.

Absent from thee, forlorn, I moan,Affliction haunts my cot;But what I bear thus all aloneAh! prithee ask me not.

HAFIZ, whose heart hath known no woe,Now feels it in excess;Ask not his boundless love to know,’Tis what he can’t express.

GAZEL VII.

HAFIZ, no longer able to endure the painful anxietude occasioned by the absence of his mistress, expatiates upon the effect it has produced upon his mind, and its afflictive operation upon his general feelings. Expostulating on her cold insensibility and total inattention to his just complaint, he describes himself as the victim of her indifference. Despondent, as he has been for some time, he begins entirely to despair, and expects to die of a broken heart.

PARAPHRASE.

Ev’ry moment thy absence I mourn,But my sighs and my tears are in vain,Since no zephyr proclaims thy return,And no zephyr announces my pain.

Night and day I’m abandon’d to grief,And what truce can extirpate my woes?Far from thee I can find no relief,Far from thee can enjoy no repose.

Ah! what else can I do but lament,When I’m doom’d such affliction to know,Such that, were I dispos’d to torment,I should wish to befall my worst foe?

Oh! what sorrow has gush’d from these eyesSince my fair from my presence has fled!How my breast has been haunted with sighs!With what wounds, O my heart! hast thou bled!

When I think of thee, forth the tears start,From my eye-lashes trickling they fall;’Tis affection that bids them depart,It is thoughts which thy image recall.

Say, shall HAFIZ to love fall a prey?Still shall grief day and night drown his eye?Shall his soul with despair pine away,While from thee he obtains not a sigh?

GAZEL VIII.

THE Poet, in this Gazel, bids the Zephyr bear to the ear of his mistress his complaint of unkind treatment from her, whose coyness and timidity are happily characterised under the form of that delicate and graceful animal the — or Fawn, an image peculiarly tender among the Greek and Roman, as well as among the Asiatic poets. The Rose and Nightingale are here again allegorically alluded to in a manner that, however repeated, still tends to delight the imagination of his Persian readers. He afterwards goes on to hint how much the charms of beauty are heightened and enhanced by a gentle and kind demeanour, and intimates that every being in the creation is delighted with his harmonious strains, except the object of his love; and, that the whole celestial choir, led on by Zorah (the planet Venus), dances in tuneful concert to the melody of his lays.

PARAPHRASE.

O! go, thou kind Zephyr, go, speed thro’ the lawn,And say with a sigh to that diffident fawn,For her ’tis I wander thro’ thicket and grove,Thro’ craggs of steep mountains in quest of her love;’Tis she that gives charms to the desert so drear,And makes the rude forest like Eden appear:Go on still to please, with long life be thou crown’d; — But, why, thou dear vender of sweetness around,Ah! why is thy songster thus slighted, O say,While absent he warbles to thee his soft lay?One morsel of pity thy parrot O give,One sigh as a sweetmeat, or else he can’t live.The Rose of her beauty is surely grown vain,To treat the fond Nightingale thus with disdain!Charms win by good nature, but not by false glare,A bird on his guard no decoy can ensnare.While sipping thy wine thou coquettest so gay,Think of him who is sighing his hours away!’Tis strange in such angel-fac’d beauties to findThe heart so obdurate, so fickle the mind!How perfect, how faultless thy charms would appear,Were constant thy love, thy affection sincere!

Can HAFIZ be scorn’d? can his lays thy ear tire, When the list’ning planets their sweetness admire; When, by Zorah led on, the celestial train In unison dance to his heavenly strain?

GAZEL IX.

THE faithful HAFIZ addresses his mistress with the strongest professions of fidelity and constancy — declares himself to have been enamoured of her beauty even from his earliest childhood — asserts the durability and inextinguishable ardency of his passion — and finally concludes by cautioning all mankind against the caprices of the sex, and the dangerous consequences of falling in love, pointing himself out, at the same time, as a striking example to deter others from being duped and driven to the same state of mental distraction.

PARAPHRASE.

Nothing, no; nothing from my heart shall tearThat damsel’s image, to my soul so dear;No, thou most graceful Cypress of the grove,There grows thy root, deep-planted by my love:Nor shall stem Fate, in grim misfortune drest,E’er scare thy lips’ memorial from my breastsIn infant life thy locks my passion mov’d,And something early told me that I lov’d: — The league, which then with love and them I made,Shall ne’er by treach’rous mem’ry be betray’d.With unborn time the innate fondness rose,And shall with deathless time expiring close:All but that love may quit my loaded heart,But that, O! never, never shall depart:Nought shall destroy it, nought its force controul;It clings so close united to my soul,That from this body sever’d were this head,E’en then my unchang’d love would not be dead.But, tho’ my wounded heart the fair pursues,Pity my feeble frailty will excuse;Sick is my soul, and why not seek to findSome bland restorative to ease my mind?Whoe’er from wild distraction would be free,And ‘scape the frenzy which thus preys on me,Let him, by HAFIZ warn’d, avoid his fate,And shun the sex, lest soon it be too late.

GAZEL X.

IN this Gazel the Zephyr is again called upon to be the messenger of love, and to waft odours, sighs, and even dust, from the feet of his mistress, to stop the tears of the disconsolate HAFIZ. He considers himself as a mere itinerant outcast, a wandering pilgrim, a poor destitute beggar, craving as a deed of charity that she would return, and strolling about he knows not where, forlorn, as it were, and bewildered in a desert, looking at every shadow for a glimpse of her, at the same time elevated with the hope, and trembling with the fear, of being or of not being successful in his pursuit. He declares, that however callous or insensible her heart may be to his affection, yet such is his extreme regard for her, that he would not even barter away a hair of her head to receive the whole universe in exchange for it. He emphatically concludes by asking, what is the advantage in having a heart emancipated from care, when the soft and tender petition of a poet only tends to make him still more the slave and vassal of her of whom he is enamoured?

PARAPHRASE.

Zephyr, should’st thou chance to roveBy the mansion of my love,From her locks ambrosial bringChoicest odours on thy wing.

Could’st thou waft me from her breastTender sighs to say I’m blest,As she lives! my soul would beSprinkled o’er with extasy.

But, if Heav’n the boon deny,Round her stately footsteps fly,With the dust that thence may rise,Stop the tears which bathe these eyes.

Lost, poor mendicant! I roamBegging, craving she would come:Where shall I thy phantom see,Where, dear nymph, a glimpse of thee?

Like the wind-tost reed my breastFann’d with hope is ne’er at rest,Throbbing, longing to excessHer fair figure to caress.

Yes, my charmer, tho’ I seeThy heart courts no love with me,Not for worlds, could they be mine,Would I give a hair of thine.

Why, O care! shall I in vainStrive to shun thy galling chain,When these strains still fail to save,And make HAFIZ more a slave.

GAZEL XI.

THE imagination of the Poet, after dwelling with admiration and enthusiasm on the fine majestic figure and fascinating deportment of his mistress, bursts forth at large into a metaphorical and glowing description of her transcendant beauties. He compares them, according to the style and imagery of the Asiatics, to admired objects in nature, and, with a figurative boldness of expression, delineates their impressive effects upon his senses. He attributes to the magic influence of her omnicreative presence in his mind, all the elegant tints, colouring, embellishments, and peinturesque beauties, with which the flowery repository of his imagination is decorated and stored. After consoling and regaling his mind with the delicious and animating sensations arising from the recollection of her former friendship, he professes his unshaken determination not to give way to reflection, but to risque, at all hazards, the recovery of her society, and never to abandon his project, however peril or despair may thwart him in the pursuit of his object.

PARAPHRASE.

Yes, thy form, my fair nymph, is of elegant mould,And proportion’d with exquisite grace;How transporting thy shape, and thy looks to behold,As sly wantons young Love in thy face.

Like the bloom of the rose, when fresh pluck’d and full-blown,Sweetly soft is thy nature and air:Like the beautiful Cypress in Paradise grown,Thou art ev’ry way charming and fair.

Thy arts so coquettish, thy feigned disdain,The soft down and sweet mole of thy cheek,Eyes, and eye-brows, and stature my senses enchain,While I gaze, not one word can I speak.

When my mind dwells on thee, what a lustre assumeAll the objects which fancy presents!On my memory thy locks leave a grateful perfume,Far more fragrant than jasmine’s sweet scents.

In this wild maze of love is no avenue foundTo escape from the torrent of grief,Yet my heart still emerges, nor fears to be drown’d,While thy friendship affords it relief.

Should I chance in thy presence to sink and expire,And before thee to reach my last goal,Let me look on thy cheek, and in peace I’ll retire,Nor repine when I give up my soul.

Though to roam ‘mid the desert and search for thee there,Nought but hazard and danger proclaim;Yet HAFIZ shall roam, and tho’ mock’d by despair,Never cease to call out on thy name.

PARAPHRASES IN PROSE.

GAZEL I.

[This Gazel is from the History of the Persian Language in the Life of Nader Shah, 8vo. Lond. 1773, p. 179, by the first Orientalist, in point of taste and research, that ever graced any country, the late Sir William Jones, whose numerous and inimitable Translations from Asiatic Authors, pre-eminently entitle him to the following just and characteristic encomium from Ausonius:

Hujus fontis aquas peregrinasferre per urbesy Un