Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Parthian Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Twelve-ish. Shade in the Murillo gardens, as satisfying as lemonade. In the heat, just for a moment, Miguel stood in front of me. The old Miguel, not the one we've got now. The fuzzy image held its hand out and led me to the old Arab wall. When we were first married, we tried to climb it in the middle of the night. A celebration. 'This wall's been here hundreds of years,' Miguel said. 'If we can conquer that, we can conquer anything.' I believed him. I open my eyes and he's gone. In these slippery stories the truth and the possible weave as unexpected lives, complicated minds and exotic spaces are sketched in with nimble words and quick wit. Ghosts torment from the past; future selves write back; the lost look about, find themselves watched, are lead astray. Keep company with thieves and murdering artists, with the couple who miss the ferry for their make-or-break holiday; the mayonnaise deliveryman who becomes a reluctant golddigger, and the psychoanalyst and his GP wife investigate a local widow's naked appearances in church. Between these pages you can never be sure quite who you'll meet next, but you can be sure that you're in safe hands. An intriguing new collection from a writer you'll want to keep an eye on.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 341

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Reviews 3

Author Bio 4

Dedication 5

The Murder of Dylan Thomas 6

Four Tales from Seville, no. 1: Fiesta 13

2: The lover 15

3: The thief 17

4: The engagement 20

The Wednesday Ghost 24

The Roll of the Sea 30

Success has made a failure of our home 37

The Woman in the Caves 43

Ferry, moon, child. 51

Death and the Maiden 56

Dragons 63

Acknowledgements 77

Copyright information 78

Reviews

‘Mark Blayney explores with an audacious imagination and stylistic brio the uncertain border between reality and illusion, identity and its dissolution, and the fragility of love. Full of surprises, this is a fine collection.’

D. M. THOMAS

‘Absolutely brilliant stories… a fascinating style, and a cunning way of manipulating us into believing one thing which in reality is something quite different. Short stories are not easy to tell; they need a patient, well-trained mind to leave us always wanting to know what comes after – I was gripped.’

VICTOR PEMBERTON

‘Fluently contriving to intrigue, amuse, surprise and unsettle all at once, these highly entertaining stories address the reader in a sharp, kinetic prose which is wide-awake to the ironies of life and the radical uncertainty of things, and they pull it off with a confidence and verve that make this collection a cracking good read.’

LINDSAY CLARKE

Author Bio

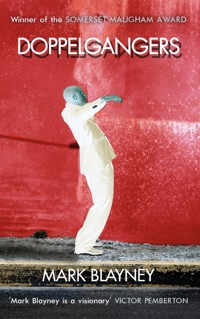

Mark Blayney won the Somerset Maugham Prize for Two Kinds of Silence. His story ‘The Murder of Dylan Thomas’ was a Seren Short Story of the Month and he’s published poems and stories in Agenda, Poetry Wales, The Interpreter’s House, The London Magazine and the delinquent. His second book Conversations with Magic Stones was described by John Bayley as ‘remarkable... as good as some of the best of Elizabeth Bowen’s, and praise does not go higher than that.’ Mark performs comedy as well as MCing regularly and his new one-man show Be your own life-coach... with ABBA tours this year.

Dedication

For Tom

The Murder of Dylan Thomas

This is a memoir of a strange town, and of how my first attempts to become a journalist were shaped and eroded there. I was sent to cover a minor scandal, in the last days of newspapers, when the oldies fretted about how news was going to survive when everyone expected to read everything for free on the net. It didn’t occur to us how it would actually go: that within a few years there would be two or three publishers and everything would be syndicated. The three guys at the top own everything, the national papers run the local papers; and the locals are essentially county papers, with a tailored front page for the town or village.

Now I’m old it’s strange to look back. I certainly didn’t realise then, as a gauche eighteen year old, how influential that weekend would be or how much I would think about it over the following decades of my life. These days there’s no monetary value in a memoir like this. I’m writing it for my own pleasure, and that’s what writing should be.

I was sent as a cub reporter; how quaint, centuries-old, that expression sounds now. The scandal wasn’t very interesting. Man buys restaurant and everything goes tits up; nothing more. The only reason it was in the papers was that the man happened to be a celebrity. I covered the story in the space of an afternoon, because everyone in the town seemed to know every detail and it wasn’t hard to email back a competent report by evening. But I was there for the weekend, and the editor told me to stay and enjoy myself. My hotel was paid for and the train was booked for Monday. At the time I thought this exceptionally generous, and it’s only later I realised it would have cost a lot of money to change the train ticket all the way back to London, so it was easier to leave me where I was.

So I stayed and was glad I did, because what I discovered was far more interesting. The first draft of anything is shit, Ernest Hemingway once wrote, and that’s why I’ve written and re-written these pages until I no longer have any recollection of which parts are true, and which are the inventions that now seem real because I’ve reworked them so many times. (You know what journalists are like.) I appreciate this is of little benefit to you as the reader – you want to know the truth, as long as I cut out the boring bits. But that’s how it is, so at least in saying this much I’m being as truthful as I can be.

My hotel, Seaview, had once been the home of Dylan Thomas. I didn’t know who he was because we didn’t get taught him at school, and I quickly became embarrassed at my lack of knowledge, as everyone in the town seemed to be talking about him. The flashes of conversation as I walked by the castle, along the estuary and beside the grand Georgian houses, were almost always about the same thing. Have you been down to the boathouse yet? And, This was the pub where he would drink, and write.

It was, as hotels were in those days, simply furnished and spacious. Dark wood, I remember. Or was it light? I should have taken pictures. I remember the outside, anyway: canary yellow, and although it had been renovated only a couple of years before, damp was discolouring the facade, breaking through as if insistent that the rough and ready of the house had to be on display, despite all attempts to paper it over.

Pictures of Dylan and his wife leaning in to each other, eyes closed, clinging on to the other’s frayed clothing. They possessed nothing, said the owner at breakfast as I looked at the photos. He had one suit, which was covered with ink. He only owned what he needed – a roof over his head, paper, pen. His only real possession was a bicycle.

They were always drunk, my bearded friend added, nodding towards the pictures. They look drunk, don’t they?

They did, they looked very drunk. I ate breakfast, which was huge. The eggs were mesmerisingly glossy. I looked at the estuary and marvelled at the silence. Yes, you could write here. My room was in the attic, tiny but immaculate. I remember the wooden struts holding it all together in elegant triangles.

The boathouse where Thomas lived for the last few years of his life propagated the legend. Everything was boxed behind glass, preserved, stuffed, the way it is in museums. A set of cufflinks – the only ones he ever had, and true to form he gave them away. A video on a loop described in rhythmic, bassooned Welsh vowels how, on the night he died at thirty-nine he’d declared, I’ve just had eighteen straight whiskies, I think that’s the record. An elderly woman in front of me gasped.

Later I saw her with the rest of her party, boarding a yellow coach. How much do you have to drink, I wondered, to collapse into a coma and die so young? The coach chugged to itself like an impatient cat as it waited to be off.

According to the iPad, he spent so much time in Browns pub that he gave their phone number as his own. I was surprised to see it open for business, as the iPad said it was closed. I realised as I stepped through the door that it may have just re-opened; the marble tiles on the floor were brand new and it smelled of paint.

Pushing the door to the left, the room was covered in dustsheets. Maybe it’s still closed after all. But the owner, sat behind a curvy desk imported from a sci-fi film, jumped up and assured me that the bar on the right was serving; they were just making the final preparations for the hotel. You can never get a meal in this town if you haven’t booked, she said, so we’re pretty excited about it.

The bar was, I remember, dusty and dark and full of old men. Or maybe it was light and airy, full of cushions and bold, colourful pictures. There was someone smoking a pipe, but that must have been someone outside, or perhaps he didn’t have any tobacco in the pipe, as this was several years after the smoking ban.

My only real recollection of people smoking in pubs is my dad, lighting one of his last cigarettes and looking gloomily at the door, saying, I’m not going to be allowed to do this next week. I was about twelve at the time. It was the greatest affront he could think of. That faraway people, who knew nothing about him, could decide that he, who just wanted to sit by a window and smoke and watch the world go by with his pint, could no longer do so.

This distant act compressed all his fury about government, society, employment and capitalism into one angry red light, flaring and crackling, stubbed hard into a ceramic bowl that would soon be whisked away and piled up with others in a skip. It didn’t matter, he died a few weeks later.

An attractive young man behind the bar served me a shy coffee, blushing as he spilt the milk. Some men at the side table looked at me. Japanese tourists in colourful, see-through macs, even though it wasn’t raining, appeared in the doorway. They wanted to know where he wrote, where he drank.

He sat by the window, the young barman piped up. There was now a curved seat, which didn’t look the best place to write. Click. The tourists took souvenirs. Click. Against the light their macs made them transparent like sweet wrappers; purple, pink, green.

A man took pictures of me; he said my hair looked good against the wood and would I mind sitting by the window. His English was excellent, and when I told him so he looked embarrassed. You are very kind.

I took my cup and saucer to the bar. There was a swirl like a question mark at the bottom of the cup. Do you want to come to a party? the barman asked. I nodded. It’s tomorrow, he said, there’s a big wedding going on. Everyone’s going. I can’t go to a wedding, I said. He said don’t worry about it, it’s the evening, not the wedding itself. You can be my plus one. He poured me a glass of ale, which I couldn’t drink.

Dressing, I watched a steady stream of people make their way down to the chapel. Fuchsia pinks, lemon yellows, sunset oranges; it was as if they had been painted against the blobby green marsh of the estuary. Above it all loomed the wood, dark and impenetrable, and heavy clouds lying across the trees, though it did not rain. I ran down the stairs and through the heavy door and the owner came down the steps after me, asking didn’t I want breakfast. I shook my head and smiled and he rubbed his hands on a teatowel. The air was fresh, I had never known air like it. I combed it through my fingers.

Down the narrow alley, past the bright blue house and imagining leaping from bench to bench. The tide was out and mudbanks lay exposed like naked shins. There were torpedo sounds; birds breaking the water and diving underneath for fish maybe. Staying to watch, I saw the sound was actually formed by slabs of sand dropping into the water.

I felt my energy ebb as I considered this happening every day. The tide washes in and smoothes the sand like silk. It drains and the sandbanks are perfect, vast wedges of caramel chocolate. Over the rest of the day, the sand falls into the water, kilo by kilo. Birds pick around it curiously, startled when a block drops. At the end of the day, the whole process starts again. The pointlessness of it, and its scale, made me queasy.

More wedding guests processed. Most were smartly dressed but some were raffish. Top hats and tails found in mouldering attics; long coats with buttons on the back; thick tweeds and heavy fabrics that we don’t make nowadays, and even then the inhabitants seemed out of place, moving slowly, pretending to be in a film. Some in bowler hats, flexing the wings of their long coats like cormorants. In my jeans and t-shirt I didn’t think I would fit in, but Richard assured me the evening would be very laid-back.

Bells rang. I sat outside the chapel and the wild flowers nodded, confirming their approval in the wind. They did not find just cause or impediment, and expressed a leaf-shrugging acceptance that you can do what you like, if you’re not troubling anyone else. I liked their philosophy.

Someone on the bench opposite me read a newspaper; there was nothing on the front about my story, which I found a good sign. Robert emerged from the chapel and put his arms round me. I turned but he put a finger over his lips. I’ve crept out, he said, I don’t do churches. We walked back into town. All that ceremonial stuff, he said, and have you ever noticed how weddings go on about death?

I shook my head. It’s all, till you shuffle off the coil, joining everyone else, the majority of people are dead, you’re just the current few who happen to be alive at the moment but it won’t be for long. It’s bizarre, he said, stopping on the path and sticking his hands in his pockets. You’d think a wedding would be about life, about celebrating living. But it really isn’t. You keep being given this reminder, smacking you round the head every five minutes just as you think the church is finally giving you permission to be happy.

The streets were empty. We ate our own sandwiches in the pub and stole the wine glasses when we had finished. Come on, he said. Richard, not Robert. We sat by the castle and watched the waves lapping the edge of the car park. The tide comes in quickly, the path floods at neap tides, he said. The posts marking the lane where cars could pass were half-submerged.

The reception was in a pink Georgian house by the river. It’s very impressive, I said as we went in. I felt like an impostor.

Yes it is, an old man with a gigantic moustache declared, leaping from behind a pot plant. The houses aren’t Welsh, he told me, as if convinced I was about to argue with him. No, no, no, they aren’t Welsh. This town isn’t Welsh, he concluded victoriously. I looked confusedly towards Robert for help but he shrugged. It’s in the depths of west Wales, I thought, how can it not be Welsh?

As if guessing what I was thinking, moustache man squared up in front of me. It’s surrounded by Wales, but it isn’t Wales.

Okay, I said nervously. First law of journalism: agree with whatever the other person is saying.

You go to the castle, he said.

Right.

Lots of signs saying that the Welsh took the town, but then they lost it again.

I see…

So who were they taking it from, hmm? He looked at me, expecting an answer. When I said nothing he continued. And think about the use of the word they. It’s not written from a Welsh point of view. This town is a republic. We quite like them really, but no one speaks Welsh, do they? He didn’t pause long enough for a reply. No one has a Welsh accent, hmm?

I haven’t been here long enough to—

We have our own Parliament. Like the Isle of Man.

Really?

The Portreeve runs this town, I’ll introduce you if you like. We set our own rules. Nothing to do with anyone else. It’s pretty remote, he said, leaning into me and revealing some cracked, blackish teeth. His moustache twitched. Don’t often get people up from London.

I’m not from—

And if we do, they don’t do well.

We don’t want to be late, said Robert, taking my arm and leading me gently away. Don’t mind him.

Is he the only person in the town not invited? I asked.

Everyone’s invited, he said, affronted. I slipped my arm into his and he did not resist. Mind you, he added as we slipped through arched doorways, he’s the only one who probably won’t come.

Cake. Some miniature houses, perfect as models, made of iced sugar and planted in paper cups. I was given a glass of champagne and welcomed enthusiastically. The wine made me dizzy and the welcome seemed unreal. Dancing couples.

Music travelled along wires and through speakers planted in unlikely places. A child under a table, in an enormous white silk skirt which ballooned up in front of her. A smaller child crawled out from beneath it. A marble statue in the corner; a woman with no top on. One of the boys, about nine he was, stood behind it and snaked a hand up and a cupped a breast. The statue ignored him poshly, a glazed look on her face.

I was introduced to a relative but had yet to see the bride or groom amongst the bustle. Adam, he said, shaking my hand briskly. There were small black hairs gnawing their way over his hands, over the knuckles, the backs of the fingers even. He had very square, very white fingernails. First law of journalism: notice the details. He looked at a picture of Dylan on the wall, young and uncertain, mouth slightly open. Terrible man, he said. The way he treated his wife. Women left right and centre. And Caitlin at home, bringing up three children, and not a bean to live on, because he drank every penny.

Why is he so famous? I asked. Adam looked at me as if I’d asked why his trousers had two legs. I mean, poets don’t become famous, I continued. Pop stars, yes, but not poets. Yet everyone here seems to know who he is – was, he’s been dead sixty years.

He was a visionary, said Adam, glancing at the picture and Dylan raised his eyebrows in mute recognition. He was like Blake; you know Blake?

I shook my head.

Don’t know what they teach kids these days.

They teach us skills, I said. Useful things, for the real world.

Oh, that.

Dylan’s portrait nodded to Adam, encouraged him to continue, fill the void. He saw through things, Adam said. He saw what was underneath.

I heard he was a sex-mad alcoholic, I replied, just to provoke. First law of journalism, generate an interesting answer.

Adam shrugged. He was a writer, of course he was a sex-mad alcoholic.

Underneath, I wondered. What is underneath?

But Adam was off, as a waiter gleamed past with a tray full of shining glasses, the wine green and sparkly, and I never found him to get my answer.

Tight t-shirt, he said, I can see your breasts. I breathed and said nothing. Slim-hipped, he said, pink jeans like rosehips. I watched, waited for more. She laps it up, she licks words like swallows. As he spoke birds swooped past. I think, I said, that I would like to walk down to the water with you. He nodded seriously, put a hand out and I took it.

The river flooded, the water swirling in and around the bridge. You could see it rise as you watched. It lapped at the stone, it climbed up the poles like ivy. The wheels of cars in the car park were already submerged. They won’t float away, Robert said. There may be a little tide damage in the morning, that’s all.

A couple stood uncertainly at the edge of the rolling water, conferring with their heads tipped like wading birds about to take off. The man shrugged and the woman glanced at her wrist and out to the horizon. Eventually he stepped forward and walked carefully through the water, placing each foot down hesitantly before continuing, reaching the car as water and mud kept his ankles submerged.

The locals know about it, Richard said. There’s usually a sign.

The car backed away magically, floating on an opaque sheen that spun circles like record grooves. The woman applauded and we joined in. They wheeled to the side of the car park, a little mud and seaweed trailing from what I recognised for the first time as literal mudguards – flaps of rubber valiantly, like soldiers, warding away mud.

We returned to the party. Towards the end young men lolled like dozing dogs. In the morning the wreckage of them will still be there, Robert told me. He led me through a small door and we were in the garden. It was night; I hadn’t realised. The castle hovered above us, black against the purple sky, jagged.

Do you want to go in, he asked.

I looked at him oddly. This is a strange town I know, but not one where the castles are open at midnight.

He grinned. We have a gate, a secret entrance. He fumbled with the key, turning it this way and that. There was a moon, but it was behind the castle and its diagonals did not fall on the doorway. Eventually we were through. I stumbled but he knew the way and guided me. We sat in a crook of stone, hollowed out in ways that were familiar to him, so he could nestle his back into the right shape and I, tucked up next to him, was uncomfortable. He took his jacket off and rolled it to create a cushion.

Far below, the estuary snaked, a black slick, to the edge of the stone. The flood surrounded us now on three sides. The benches were submerged and nothing could be seen of the stone bridge. The car park was wet to the gate and one car remained in the centre: a Mercedes, its logo proud on its bonnet like a CND symbol, wheels underwater.

As Richard leaned in towards me and slipped a hand into my top, a white cone swept across the edge of the water: the bride, and less visible behind her, the groom. She floated like a beacon, illuminating him in the wake she left behind. Robert kissed my ear, my neck, and I raised my head to let him, which gave me a clearer view of what was happening below. Oona – I had seen her name in wobbly black icing on the cake – seemed to glide, then billow, towards the car. As she descended into the water, Simon – his icing was even wobblier – followed, reaching a hand out.

I stayed Richard’s hand as it reached into the hem of my jeans; three buttons down, two to go. He moved closer. Too cold? he asked. Shall we go to my room?

Look, I said, and to begin with he thought I was changing my mind, and then he did look.

They were at the car now. Are they drunk? he said.

Is it theirs? I asked.

He shook his head, and anyway, he said, why would they drive on their wedding day? He drew a line on my thigh.

They’re crazy. Or they’re stealing the car – a wedding prank. Or they’ve decided, in their elation, that they need to rescue it for whoever it belongs to.

Oona dropped onto the water and her dress cascaded behind her. Come on, Robert said, jumping down from the stone. We need to go the long way round, he called over his shoulder. I heard lapping water. We ran through the arch and he showed me a shortcut through hedges.

Simon stood by the edge, legs slightly apart, dripping wet but tall and serene, James Bond newly emerged from an underwater adventure.

Oona stood near him, her hair occasionally tossing dolphins of water.

Between them was a small child, bedraggled, holding on to Oona’s dress like a magic, satin blanket.

We lay in the wet grass by the stone and rolled together, and I looked at the moon, which, from behind a thin cloud, became luminously whole. Much later, bells woke us.

We walked in silence to the house and slept deeply, for those hours of summer when it’s light but no one’s fully awake. I got up earlier than Richard and pretended to have a hangover. I poured pint glasses of water for us both and waited for him. I sat by the bed and watched him sleep, his face blueish in the light. He snored and rolled over. I got dressed, not particularly quietly, and eventually walked down the stairs and through the door.

The town slept and the water had returned to normal. Seeing it now, there was no evidence that last night had happened. The tables were not damp and the posts were undamaged, and there was no sign of the wedding.

The town was dead apart from one gaping door. Inside I breathed musty books. In those days there were still one or two second-hand bookshops left; it seems strange to us now, all that space, covered with virtually worthless stock, but at the time people still liked flicking through old volumes and paying a pound or so for them. (A pound then was about six times what it is now).

I bought a biography and some poems. The owner was a happy soul, burrowed in the corner, a literate vole. He paused from wrapping a slim first edition in brown paper and stacked my pound coins in front of him.

On the trail are we, he asked mildly.

Just curious to find out more.

He nodded. You know nothing anyone says about anything to do with Dylan is true, don’t you?

Oh?

But he had returned to his careful wrapping, a man for whom every day is Christmas. I blinked in the sunlight.

I wrote this much last night and now it’s the morning and I’m looking down to the sea. Five o’clock and no one is up but the light is strong and the day marches. The older you get, the less you sleep. I know you know that, but it’s what old people say, so I’m saying it. It keeps you awake. The clot in the leg or the brain can carry you off in a moment: awareness of this means that when you come to consciousness early in the day, you get up. My legs are stiff, my body feels tired though I am not. It’s is a strange sensation you get when you’re elderly. Strange too, being young. I’m a different person now, although I suppose it must have been me.

I walked up to the castle and, with a few hours still to kill before my train, paid my £3 and went through the gates. It didn’t seem right to knock on the pink house just to get in for free. The till was so loud that I didn’t hear what the boy handing me the ticket said, and by the time I opened my mouth to ask him to repeat it, he’d gone back to his visitor satisfaction checklist, which he ticked diligently.

Through the gatehouse, and the familiar shudder when you enter an ancient place. How many people have walked these exact steps and seen these exact things, over so many centuries. Before electricity, nylon, radio, saxophones, three-pronged forks, plastic, elastic, railway timetables, Saturn’s discovery, penicillin, aeroplanes, branded goods and chocolate, piano keys and mirrors, people touched these stones and contemplated this estuary.

How does a fridge work? How do we get through life knowing so little? I stood at the top and looked down on the glistening water and did not see the signs that said, do not climb up here, it is dangerous.

There was a summerhouse: a round mussel stuck to the side of the stone where Dylan wrote stories and Richard Hughes wrote A High Wind in Jamaica.

Now I am old and interested, I read somewhere that Hughes owned Seaview and let Dylan live in it; Dylan never had the money for a house. The first he borrowed, the second he was given. But it’s Dylan’s name on a plaque outside the grand yellow Georgian exterior where I’m staying. The ghost of Richard Hughes might be pretty annoyed, should he come walking up the street and see what the house looks like now.

The young me was interested in none of this, she was walking along the stone balustrade and seeing gulls fight and spat with each other along the ledges below. I slipped off the wall and knocked my head sharply against the stone: a ringing sensation that made me momentarily think, is this how I go, a blow to the head and an early death? Yet here I am now, ninety-one and remembering this; so we know I came to no harm.

Richard Hughes wrote the world’s first radio play; where’s his blue plaque? And we must not be like Vernon Watkins, poor Vernon Watkins who spent all day droning in a bank, refusing promotion, staying lowly, so he could work breakfasts, lunchtimes, evenings on his poetry. He stayed in each night to write after work. Dylan, according to the long-suffering Caitlin, went out every single night of their marriage. Why did she stay with him? He earned no money, he womanised, he drank.

We don’t forgive him the women, although as I saw him heading towards me, brow lowered, fat cigarette shoved in his mouth like a spoon, I could understand it. Were I a lover, I would love him. Were I a wife, I would stay. He paused then continued towards me, curly hair high on a balding head, yellowy fingers. Crossing the forecourt was the same man, older, fatter, face bloated.

On a stone, the same man scribbling in a notebook. By the entrance he argued with a woman. I watched all these versions of Dylan and tried to think of the killer question. First law of: always be ready with a question.

One in a bow tie said, never believe that you cannot change the past.

Another read a poem that I rather liked, but as he turned and read it differently, it sounded terrible.

The older one, although he cannot have been as old as he seemed, looked me up and down and said, be quick. Be quick.

Am I really ninety-one and remembering this, or is it actually the next morning and I’m in a hospital bed, dreaming that I’m old, because I’m disorientated? We’ll never know, certainly not now we are on the last page of the story.

I looked across the stone walls and saw Robert in the garden, naked. He held a sheaf of papers and recited from them.

Dylan liked to sit with his arm on her neck, he said, his finger hooked in her bra. He dropped the page and read from another one. Bed me now, she said, come, bed me now, now.

He turned and walked towards the house, and did not see me.

‘There is no turning place: go back’, a slate sign with white, horror-film paint reads.

The narrow dogleg road is hemmed with double yellow lines, stitchings for a boot. At a fence two gatekeeper butterflies bordered me, one with darker colouring. Later, on the train I remembered this and looked it up on the iPad; turns out it was actually the Saldany Moth. Sometimes it is out in the daytime, disguising itself as a gatekeeper. The Saldany Moth; I had never heard of it before, although it sounds familiar. Lepidoptery is not something I’m up to speed with. First law of: do your research diligently.

At the Boathouse I admired the vastness of the view and smallness of the rooms. There was an outside café, its terrace cleared of chairs and parasols because the flood had only just gone down.

It even floods here? an elderly lady asked as she picked over the crumbled cliff of her scones. Yes, replied the owner, also elderly. Two more elderly ladies sat at the tables, studying the sea. One more behind me, nodding slowly. It was amok with elderly ladies. I was in an elderlylady of elderly ladies.

I opened my book on Dylan and the old spine cracked.

Nothing in that is true. A bony, blue finger jabbed the pages.

Really? How do you know? First law of.

Because I knew him. She settled opposite me and winced at the hard wood.

Elderly ladies have pale blue eyes; they bore at you, waiting to peck you like a worm. When do old ladies become old? There is no age you can fix it at. (I know now, but I was thinking this then.)

He wasn’t the boozer everyone claims he was, she says, her voice surprisingly soft after you’ve had the eyes at you. He couldn’t afford booze, he never had any money.

I must have looked questioning because she continued. It wasn’t that he was drunk, it was that he couldn’t take his drink. She sat back. Quite a different problem, of course. So he appeared heavily drunk when he’d only had a few.

People still said of course in those days, like the previous generation said you see, and to us it sounds imperious and to them it was normal. A vast pot of tea appeared. I wondered if it was somehow for both of us, but there was one cup, one saucer.

He liked living here because he could have a couple of drinks quietly in the pub – did you go to Browns? – I nodded – and watch the people going by, and write.

She pursed her lips and rattled the teapot. Old ladies like their tea strong.

I knew his wife too. They were kind, gentle people. It’s all been exaggerated. Even the video they have on upstairs – she nodded to the house – has that line about the whiskies, the eighteen whiskies. It isn’t real.

I thought he… everyone says… well known that…

She sipped her tea between each part of the list.

He spoke fiction. Everything he said was made up.

I nodded. Be patient, let her talk.

Look at the letters, you soon see that. He spins yarns, he boasts, he invents personalities.

So… why did he die so young, if he wasn’t drinking that much?

One of her clones took the tray away. Would you like cake too? she asked. I shook my head. There was a ringing sensation that buzzed around my ears.

When he was in the States, he was ill. He was always ill. Pleurisy, asthma, bronchitis, you name it.

Dylan sits on the wall, swinging his little legs. I was a sickly child, he says, as he puffs on the stub of a cigarette.

The elderly lady examined the remains of her cake. A doctor there thought he was drunk. Sedated him. Gave him cortisone, and morphine. Together!

Dylan stands beside me, looking out to the estuary. He turns and glowers at me. And, he says, forehead a granite mountain, benzedrine. Benzedrine!

The old woman leant forward. Can you believe it?

I suppose… that’s what they did in those days.

By the end table, Dylan shakes his head and points at me. I follow him and we go through the low-beamed door, Dylan waddling ahead, me ducking to fit inside. Past the corridor is a white-walled room, pipes running at shoulder height, ancient electricity sockets like boles on branches. Dylan lies in a rickety bed, motionless, and as I stare at him a woman breaks away from two white-coated juniors, their horn-rimmed glasses jiggling comically on their heads. Rushes over to Dylan and glares at him.

Is the bloody man dead yet she says, before she’s bundled away again – or doesn’t say, because I’m not quite sure I heard her right. The more I think about it, the less sure I am that it’s what she said, but I can’t remember now to report differently. It’s all chaos and movement – photographers are there now, leaning over the railed balcony, flashlights illuminating Dylan’s face and making him alive, his lips and eyebrows twitching in the changing beams of light.

We wait for him to say something, pause dutifully to hear what he might come up with. We’ve done all we can, explains the doctor, his voice gravelly and American. As much as we possibly could.

He is a special patient, you can see the doctor thinking; we have taken far more care over him than we normally would. We thought of everything we could and gave it to him, because the eyes of the world’s press are on us; what would it say if we were accused of neglecting him?

I’m pushed out along with the other journalists and glimpse Caitlin’s face, the disbelief, the wail of certainty. Outside, the calm of the estuary washed over me. The elderly lady was demolishing the last of her cake. For some reason, she said, this particular doctor decided to overdo it massively.

I see.

That’s what sent him into the coma.

So how, why…? How could they make a mistake like that?

She looked this way and that, over my head to a temporary logjam of elderly ladies, back to the cottage, and down to the dog house. The blue eyes bored in all kinds of directions then homed back in on me. Well, who knows? I don’t want to invent things after the event. Possibly, he was an undiagnosed diabetic. That would explain a lot. Anyway. One way or the other, all the wrong stuff to give him.

Yes.

Tragic doesn’t cover it. All those years he didn’t have, the poetry he didn’t write.

Indeed.

He’d be a hundred now.

As must you be, I thought, touching the back of my head, where a bruise had formed.

It would be wrong to use the word murder, she said, touching the tips of her teeth as if they might crack and shatter at any moment.

?

That’s the kind of word journalists would use.

Uh-huh…

But I would use the word manslaughter. Yes. The Manslaughter of Dylan Thomas. Would that be a good title for a story? She drained her tea and grimaced, a brown skull in the making.

Probably not, she concluded, in this day and age.

Back in the city on a Friday night I made my way home past laughing teenagers falling drunk from pubs and clubs and nearly getting hit by buses.

I suppose it makes sense. Even if he was knocking them back at an extreme rate, you don’t fall into a coma and die at thirty-nine. What the old woman said about the doctor has more of the ring of truth about it.

First law of, question everything. We read something and we take it as fact. Why would we not?

The story about the local scandal, for which I was paid and which was printed, is long forgotten. And with Dylan, what I found by talking to people was inconsistent, unverifiable, not reported – so less real.

Nowadays, whenever I say the word ‘net’ and the screen lights up, it makes me dizzy. The information, the text. The stream of it, the endless content. It is real because it is written down.

So that’s my version. The official version is still what it says on Wikipedia – look it up. After you’ve read this, you may go there and update it and things will be different. Or, they might have been re-updated back to where they were before. Truths get rounded up to tell a story.

Anyway, we like our heroes dramatic and exciting. We want our stories neat and strong like those eighteen whiskies, and we want to know the beginning and the end. Our icons die young and stay compelling, they do not go gently into old age and wear a cardigan.

I saw a new drama about Dylan Thomas. It trotted out the same old things. The drinking, the coma. Perhaps I am wrong. I am ninety I’m losing track of it now.

There was no train station but I came from London on the train. I must have got a bus from the village to the next town; I just don’t remember it. I did see a stream, its sides deep and narrow, and in front of it a terrace with names like Cutting House and Rail Cottage.

Perhaps this was the ghost of the train line, that once connected Carmarthen to Laugharne and opened the town up to the Georgians, who built their proud, colourful houses there. Now it is remote again, as it was centuries before, before it was Welsh, before it was French.

Oh yes! Who cares about celebrity front pages when there’s so much embedded in old stone walls like milk teeth to be slowly, satisfyingly, dislodged? What news is there anyway, apart from climate change – we need to fix it, and fix it urgently…?

It is a republic, and it has its own currency.

Probably time I ate something. I walk into a pub and sit down, and someone asks me if I’m all right. There is no menu. I say I’ll have whatever they’ve got.

Notes. I am ninety-three today, or is it ninety-two. Richard Hughes did not live in Seaview. There is no such thing as the Saldany Moth.