Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

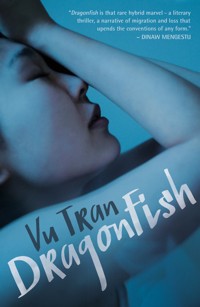

New York Times Notable Book 2015 Vu Tran has written a thrilling and cinematic work of sophisticated suspense and haunting lyricism set in motion by characters who can neither trust each other nor trust themselves. This remarkable debut is a noir page-turner resonant with the lasting reverberations of lives lost and lives remade a generation ago. Robert, an Oakland cop, still can't let go of Suzy, the enigmatic Vietnamese wife who left him two years ago. Now she's disappeared from her new husband, Sonny, a violent Vietnamese smuggler and gambler who is blackmailing Robert into finding her for him. As he pursues her through the sleek and seamy gambling dens of Las Vegas, shadowed by Sonny's sadistic son, 'Junior', and assisted by unexpected and reluctant allies, Robert learns more about his ex-wife than he ever did during their marriage. He finds himself chasing the ghosts of her past, one that reaches back to a refugee camp in Malaysia after the fall of Saigon, and his investigation uncovers the existence of an elusive packet of her secret letters to someone she left behind long ago. As Robert starts illuminating the dark corners of Suzy's life, the legacy of her sins threatens to immolate them all.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 442

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2016

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

DRAGONFISH

New York Times ‘Notable Book’ of 2015

Vu Tran has written a thrilling and cinematic work of sophisticated suspense and haunting lyricism set in motion by characters who can neither trust each other nor trust themselves. This remarkable debut is a noir page-turner resonant with the lasting reverberations of lives lost and lives remade a generation ago.

Robert, an Oakland cop, still can’t let go of Suzy, the enigmatic Vietnamese wife who left him two years ago. Now she’s disappeared from her new husband, Sonny, a violent Vietnamese smuggler and gambler who is blackmailing Robert into finding her for him.

As he pursues her through the sleek and seamy gambling dens of Las Vegas, shadowed by Sonny’s sadistic son, ‘Junior’, and assisted by unexpected and reluctant allies, Robert learns more about his ex-wife than he ever did during their marriage. He finds himself chasing the ghosts of her past, one that reaches back to a refugee camp in Malaysia after the fall of Saigon, and his investigation uncovers the existence of an elusive packet of her secret letters to someone she left behind long ago.

As Robert starts illuminating the dark corners of Suzy’s life, the legacy of her sins threatens to immolate them all.

About the Author

Vu Tran was born in Saigon in 1975, five months after the city fell to the North Vietnamese and five months after his father, a captain in the South Vietnamese Air Force, was forced to flee the country. In the spring of 1980, Tran, his mother, and his seven-year-old sister escaped Vietnam by boat, spending five days at sea. They ended up in Malaysia and settled in a refugee camp on the island of Pulau Bidong, off the Malaysian coast. Four months later, Tran’s father sponsored them from America, and in September, they all reunited in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where he met his father for the first time.

Praise forDragonfish

‘A strong first novel for its risk taking, for its collapsing of genre, for its elegant language and its mediation of a history that is integral to post-1960s American identity yet often ignored… above all, Tran’s novel is a refreshing and entertaining story’ – New York Times

‘A superb debut novel…that takes the noir basics and infuses them with the bitters of loss and isolation peculiar to the refugee and immigrant tale’ – Fresh Air

‘A hard-hitting debut novel… [Suzy is] a mystery no one can solve, particularly the people turning all their efforts in the wrong direction. But while their efforts aren’t fruitful, they’re absorbing. And they speak to the way everyone is a bit of an enigma to other people, no matter how many words they put into the effort to be understood’ – NPR Books

‘Transfixing… like such writers as Caryl Phillips, Dinaw Mengestu and Edwidge Danticat, [Tran] is devoted to capturing the immigrant experience and widening everyone’s understanding of its particular as well as universal truths’ – Chicago Tribune

‘A sophisticated mystery anchored in one woman’s quest to make amends with the daughter she abandoned, Dragonfish delicately capsizes our notions of what it means to long for escape from the prisons of our own making’ – Ploughshares

‘Like Gatsby, the characters in Tran’s novel yearn for something unattainable… This and the feeling that there will only be a tragic end are what elevate Dragonfish beyond its bookstore genre’ – Los Angeles Review of Books

‘Nuanced and elegiac… Vu Tran takes a strikingly poetic and profoundly evocative approach to the conventions of crime fiction in this supple, sensitive, wrenching, and suspenseful tale of exile, loss, risk, violence, and the failure of love’ – Booklist

www.vutranwriter.com

for my parents

Contents

PART ONE

Kapitel 1

Kapitel 2

Kapitel 3

Kapitel 4

Kapitel 5

PART TWO

PART THREE

Kapitel 6

Kapitel 7

Kapitel 8

Kapitel 9

Kapitel 10

Kapitel 11

PART FOUR

PART FIVE

Kapitel 12

Kapitel 13

Kapitel 14

Kapitel 15

Kapitel 16

Kapitel 17

Kapitel 18

Acknowledgments

Copyright

Our first night at sea, you cried for your father. You buried your face in my lap and clenched a fist to your ear as if to shut out my voice. I reminded you that we had to leave home and he could not make the trip with us. He would catch up with us soon. But you kept shaking your head. I couldn’t tell if I was failing to comfort you or if you were already, at four years old, refusing to believe in lies. You turned away from me, so alone in your distress that I no longer wanted to console you. I had never been able to anyway. Only he could soothe you. But why was I, even now, not enough? Did you imagine that I too would die without him?

Eventually you drifted off to sleep along with everyone around us. People were lying side by side, draped across each other’s legs, sitting and leaning against what they could. In the next nine days, there would be thirst and hunger, sickness, death. But that first night we had at last made it out to sea, all ninety of us, and as our boat bobbed along the waves, everyone slept soundly.

I sat awake just beneath the gunwale with the sea spraying the crown of my head, and I listened to the boat’s engine sputtering us toward Malaysia and farther and farther away from home. It was the sound of us leaving everything behind.

The truth was that I too thought only of your father. On the morning we left, I held you in the darkness before dawn and lingered with him as others called for us in the doorway. He kissed your forehead as you slept on my shoulder. Then he looked at me, placed his hand briefly on my arm before passing it over his shaven head. I could see the sickness in his face. The uncertainty too, clouding his always calm demeanor. He had already said good-bye in his thoughts and did not know now how to say it again in person. I did not want to go, but he had forced me. For her, he said, and looked at you one last time. Then he pushed me out the door.

If you ever read this, you should know that everything I write is necessary to explain what I later did. You are a woman now, and you will understand that I write this not as your mother but as a woman too.

On that first night, as I watched your chest rise and fall with the sea, I wished you away. I prayed to God that I might fall asleep and that when I awoke you would be gone.

PART ONE

1

It was three in the morning and dark in my apartment. I stood half naked behind the front door, peering through the peephole at my vacant porch. My voice had come out small and childish and like someone else’s voice calling from the bottom of a well.

‘Who’s there?’ I said again, louder, more forceful this time. The porch light flickered but I could see only the lonely rail of my balcony, the vague silhouette of trees beyond it.

I grabbed my officer jacket off the kitchen counter and slipped it on. I steadied the gun behind me, then slowly opened the door and let in the cool December air. The hair on my chest and legs bristled. I stepped onto the porch. No one on the stairwell. No one by the mailboxes. A sweeping breeze from the bay made my legs buckle. I peered over my second-floor balcony. In the darkened courtyard, strung over the elm trees, a constellation of white Christmas lights swayed.

I returned inside and locked the door. I crawled back into bed, back under the warm covers as though wrapping myself in the darkness of the room.

The two knocks that had awakened me resounded in my head, this time thunderous and impatient and so full of the echo of night that I asked myself again if I had heard anything at all. Could a knocking in your dreams wake you?

Some minutes passed before I placed my gun back on the nightstand.

‘No one out there to hurt you but yourself,’ my father, a devout atheist, used to tell me. I never took this literally so much as personally, because my father knew better than anyone how selfish and shortsighted I can be. But whether he was warning me about myself or just naively reassuring me about the world, I have chosen, in my twenty years as police, to believe in his words as one might in aliens or the hereafter. They’ve become, it turns out, a mantra for self-preservation. Cops get as scared as anyone, but you develop a certain fearlessness on the job that you wear like an extra uniform, and people will know it’s there like your shadow slipping its hand over their shoulder, and intimidated or not they’ll think twice about hurting you. It’s an armor of faith, a wish etched in stone. Go ask a soldier who’s been to war. Or a priest. Or a magician. Without it, without that role to play, everything is a cold dark room in the night.

My phone rang at six the next morning, an hour after my alarm woke me. I was already in uniform, coffee cup in hand and minutes away from walking out the door.As soon as I answered, the phone went dead – just like the previous morning.

I went to the window and peeked through the mini blinds at the parking lot below. No one was up and about at that early hour, and the morning was still a stubborn shade of night. I made a fist of my left hand, unfurled it. My fingers had healed along with the pink scar on my wrist, but a warmth of unforgotten pain bloomed again. I stood there gazing at the lot until I finished my coffee.

Two days before this, I had come home from my patrol and found the welcome mat slightly crooked. Easily explainable, I figured, since any number of people – mailman, deliveryman, one of those door-to-door religious types – could have come knocking during the day. But once inside I noticed an unfamiliar smell, like burnt sugar, like someone had been cooking in the apartment, which I never do. In my bedroom, the pillows on the bed were in the right place but looked oddly askew, and one of my desk drawers had been left an inch open. It’s always been the little things I notice. Show me a man with three eyes, and I’ll point out his dirty fingernails.

The same smell greeted me the next evening as soon as I opened the front door. It followed me through the living room, the kitchen, the bedroom, the living room, the kitchen, fading at times so that I found myself sniffing the air to reclaim it, as I did as a boy when I roamed the house for hours in search of a lost toy or some trivial thought that had slipped my mind. Then the smell vanished altogether. Half an hour passed before I finally went to the bathroom and saw that the faucet was running a thin stream of water. I shut it off, more than certain that I had checked it before leaving that morning, something I always did at least twice.

I closed all the window blinds and spent the next two hours combing through all my drawers and shelves, opening cabinets and closets, searching the entire apartment for something missing or out of place, altered in some way. I knew it was ridiculous. Why would they go sifting through my medicine cabinet or my socks? Why move my books around? I suppose checking everything made everything mine again, if only temporarily.

That night I went to bed with my gun on the nightstand, something I hadn’t done in nearly five months, since those first few weeks back from the desert.

I’d been trained on the force to trust my gut, or at least respect it enough to never dismiss it; but it crossed my mind that I was imagining all this, that in the previous five months I’d been glancing over my shoulder at shadows and flickering lights. You fixate on things long enough and you might as well be paranoid, like staring at yourself in the mirror until you start peering at what’s reflected behind you.

When the phantom door knocks awoke me that same night, I lay in bed afterward and waited. I was that boy again, hearing the front door slam shut in the middle of the night and measuring the loudness and swiftness and emotion of that sound and whether it was my mother or father who’d left this time, and then waiting for the sound again until sleep washed away the world.

The lesson of my childhood was that if you anticipate misfortune, you make it hurt less. It’s a fool’s truth, but what truth isn’t?

When I got home the following evening, I stayed in my car and stared for some time at the dark windows of my apartment. I was still in uniform but driving my old blue Chrysler. A drowsy fog crawled in from the Oakland bay, a cataract on the sunset, the day, which now felt worn. ‘Empty Garden’ played on the radio, a slow sad song I hadn’t heard since my twenties. I remembered the old music video, Elton John playing a piano in a vacant concrete courtyard amid autumn leaves and twilight shadows. I sat back and scanned the complex of buildings surrounding me and thought of Suzy and the flowers that decorated every corner of our old house, and at the pit of me was not sadness or anger but the hollowness of forgetting how to need someone.

Three kids on bicycles glided past my car through fresh puddles left by the sprinklers. Some twenty yards away, an elderly man strolled the courtyard with his Chihuahua like a scared baby in his arms. In the building that faced me, three college guys were leaning over their balcony, smoking and leering at a pretty redhead who passed below them with a baby stroller. Then I saw a skinny Asian kid – a teenager – walk in front of my car, turn, and approach the window. He smiled and gestured for me to roll it down. His hands looked empty. He was wearing a Dodgers cap and an oversize blue Dodgers jacket zipped all the way to his throat. His smile was like a pose for a camera, and when he bent down to face me, he was all teeth.

I cracked open my window.

‘Hello, Officer,’ he said. ‘Nice evening, huh?’ He slipped me a folded note through the crack, and before I could say anything, he jogged away around the corner of the building.

I recognized the yellow paper, the Oakland PD logo, ripped from the notepad on my kitchen table. The words were neatly printed in red ink: We’ve come from Las Vegas. Leave your gun in the car and come into your apartment. We just want to talk. Follow these instructions and no one will be harmed.

That last line lingered on my lips as I refolded the note and slipped it into my breast pocket, glaring again at the windows of my apartment. Why would they warn me? Why give me a chance to walk away? I considered calling in for help, but had to remind myself that if I hadn’t told a soul about what happened five months ago, there was no explaining it now, at least not to anyone who could help. I could have driven away too, but I’d done that before and it had only led me here, to this moment. Or so I suspected.

And that was really the thing: whatever it was, I just needed to know. Nothing more exhausting than the imagination.

I pulled my gun out of its holster and made a show of holding it over the steering wheel before placing it into my glove compartment.

Walking away from the car felt like leaving a warm bed. I had lived in the complex for over two years, ever since the divorce, and liked it well enough, but only then, as I was trudging up the path toward my apartment, did I see how its tranquil beauty seemed like a postcard of someone else’s life: the ivory stucco buildings leaning into shadow, hugged by tall trees and trimmed bushes and small perfect squares of lawn drowned now, even in winter, by the evening sprinklers. I began my climb up the stairwell. I noticed for the first time how craggy the stone steps were, how awfully they’d scrape at your skin if you were to go falling down the stairs.

Not sure what to do at my own front door, I knocked. There was no answer, so I slowly turned the knob. The door was unlocked. It opened into darkness. As soon as I stepped inside, the lamp in the living room clicked on.

There were two young Asian men standing side by side in front of the TV set. The taller one spoke up in perfect English: ‘Close the door, please.’

I remained in the doorway and gripped the doorknob, one foot still lingering on the porch. I remembered the last line of their note and took another step inside, nudging the door shut with my heel.

It’s always difficult to tell with Asians, but the two of them could have been no older than twenty-five. The short one sported a goatee and slick hair and stood ashing his cigarette into my potted cactus, his wiry frame wrapped in a shiny black leather jacket. The other one, buzz-cut and sturdy in jeans and a bomber jacket, was a foot taller and moved that way, having just, without a word or glance, handed his binoculars to his partner, who dutifully set them atop the TV. I saw no sign of a gun on either yet, which bothered me more than if they’d already had one pointed at my head. They were not nervous, though they expected me to be. The goateed one, like their messenger outside, acted happy to see me; he had nodded when our eyes met, right after the lamp flickered him into existence. But it was the taller, stoic one who again spoke.

‘You are Officer Robert Ruen.’

‘Who’re you? Why are you in my home?’

‘I’m sure you can guess. You came up, didn’t you?’

‘Did I have a choice?’

He said something to the goateed kid that I did not understand, but I knew for certain then that they were Vietnamese.

Casually, the kid put out his cigarette in the cactus pot and approached me with a sly grin and his palms out like he wanted a hug. ‘If you don’t mind, Mr Officer, I’m gonna search you right now. Wanna make sure we all on even ground.’

I hesitated at first, not sure yet whether I should cooperate or play dumb and tell him to search himself. His pleasantness both irked and intimidated me. I put my hands on the front door and let him pat me down. He was half my size, but his hands were solid, with weight and intention behind them. Satisfied, he gestured for me to make myself comfortable on my own couch, which I did after quickly sniffing him and smelling nothing but cigarettes.

They’d been waiting for some time. A couple of my travel magazines lay open on the coffee table beside two open cans of Coke from my fridge, and the TV remote sat atop the TV instead of its usual resting place on the arm of the sofa. I was surprised they hadn’t kicked off their shoes and made coffee.

The kid watched me as I, by force of habit, slipped off my loafers and set them neatly to the side. He chuckled lazily and turned to his partner. ‘I think we dirtied up his carpet.’

His partner looked at his watch, then at my shoes. Again he spoke in Vietnamese. The kid threw him an exaggerated frown, but he repeated himself and was already silently unlacing a boot. A moment later they had both tossed their shoes onto the tile floor by the front door.

‘Our Christmas present to you,’ the kid said to me in his white socks.

‘How did you get in here?’

‘Through the front door. Simmer down, Mr Officer. We just waiting for a phone call.’ He shut up for the moment, waiting like his partner.

On the wall behind them hung the samurai sword I had bought ages ago at a flea market for forty bucks. I had unsheathed it once or twice to admire it, and now wondered how sharp it actually was.

‘Hey,’ the kid said, struck by something. ‘I got something else for you.’

Though I was going nowhere, he gestured for me to remain seated. He arched his brow mischievously at me, as if at some eager child at a birthday party, and reached into his jacket pocket. I held my breath as he pulled out another cigarette, which he put to his lips. From the other pocket, he revealed a silver flask. Holding out an index finger like a perch for a bird, he carefully poured the contents of the flask over the length of it. He raised it to his face and flicked his lighter. The finger ignited in a calm blue flame, which he promptly used to light his cigarette. He held up the finger like a candle, blew a lazy plume of smoke over it, and watched it burn itself out as he flashed his jack-o’lantern grin. I couldn’t tell if he was trying to scare me, entertain me, or make fun of me.

His partner looked on with glassy, tired eyes. We exchanged an awkward glance before he looked away as if embarrassed by this brief talent show.

His cell phone chimed and he brought it carefully to his ear, nodding at the kid to take a post by the door. He spoke Vietnamese into the phone as he gave me another once-over. He moved into the hallway between my bathroom and bedroom, murmuring into the shadows. After a minute, he came back and handed me the phone.

The line was silent.

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘You. Robert Ruen.’ It was a declaration, not a question – an older man’s voice, loud and somehow childish, the accent unmistakably Vietnamese. ‘Say something to me.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘You. Your voice, man – I don’t forget thing like this.’

It might have been his broken English or how quickly he spoke, but he sounded something like a puppet. He was smoking, sucking in his breath fast and exhaling his impatience into the phone.

‘You’ve made a mistake,’ I said.

‘You got bad memory? You know who I am.’

‘I have no idea –’

‘Las Vegas, man. I know you come here. You think I’m dummy I not figure out?’ He snorted and spat, as if to underline his point. ‘In Vietnam, we say beautiful die, but ugly never go away. For policeman, you do some bad fucking thing. You know how long I wait to talk to you? I been dream about this. I see your face in my fucking dream.’

My houseguests were stirring. The tall one slowly unzipped his jacket, and the kid drifted behind me. I could still see curls of his cigarette smoke.

I spoke calmly into the phone, ‘What do you want me to say?’

‘Tell me.’

‘Tell you what?’

‘You fucking know.’

‘I don’t know anything about anything. Just what the hell are you talking about?’

He sounded like he was thinking. Then he replied, as if repeating himself, ‘Suzy.’

The name drained me all at once of any effort to deny its importance. It was like he had slapped me to shut me up.

I think back on it now, and this was the moment I felt the full weight of the things I’d already lost – the last moment before everything that would later happen became inevitable.

I heard movement behind me. On cue, the goateed kid appeared at my shoulder. I did not see the gun until it was pointed, a dark hard glimmering thing, squarely at my temple.

The voice spoke again over the line. ‘I ask you one time. Where is she?’

2

Five months before all this, I drove into Vegas on a sweltering July evening just before sunset. From the highway, I could see the Strip in the distance, but also a lone dark cloud above it, flushed on a bed of light and glowing alien and purplish in the sky. I was convinced it was a UFO and kept gazing at it before nearly hitting the truck ahead of me. That jolted me out of my exhaustion.

Half an hour later, the guy at the gas station told me about the beam of light from atop that giant pyramid casino, which you can spot from anywhere in the city, even from space if no clouds are in the way.

‘Sorry, man,’ he said like he was consoling me.

I must have looked disappointed.

The drive from Oakland had taken me all day, so I checked into the Motel 6 near Chinatown and fell asleep with my shoes on and my five-shot still strapped to my ankle. I slept stupid for ten hours straight and woke up at six in the morning, my mouth and nostrils so dry it felt like someone had shoveled dirt over me in the night. The sun had barely risen, but it was already a hundred degrees outside. Not even a wisp of a cloud.

After a long cold shower, I walked to the front office. The clerk from last night – an old Chinese guy who spoke English about as well as I spoke Chinese – was slurping his breakfast and watching TV behind the counter. He looked up when I knocked on the counter, but did not set down his chopsticks until he saw me brandish cash. I’d already paid him for last night’s stay, and now I handed him a hundred for two more nights. He said nothing and hardly looked at me before handing me a receipt and diving back into his noodles. When I asked him where I could get some eggs, he mumbled a few incomprehensible words, his mouth stuffed, glistening. I felt like slapping the noodles out of his mouth but I turned and walked out before he could annoy me any further. Ever since Suzy left me, I’d learned to curb my temper. Let it sleep a little, save it for another, more necessary day.

In the strip mall across the street, I had some coffee at a doughnut shop and spent an hour thumbing mindlessly through a couple of Asian newspapers, waiting for the pho restaurant next door to open. I hoped they made it like Suzy used to – the beef thinly sliced and not too gristly, the noodles soft, the broth clear and flavorful. Turned out theirs was even better, which finally cheered me up, though it reminded me of something her best friend – a Vietnamese woman named Happy, of all things – once told me years ago when she was over at the house for Sunday pho. Suzy had been mad at me that morning for nodding off at church, as I often did since my weekend patrols didn’t end until midnight, and though she knew I’d only converted for her and had never taken churchgoing seriously, she chewed me out all the way home, and with more spite than usual. So when she stepped outside to smoke after lunch, I asked Happy, ‘What’s bugging her lately?’ Happy was her one good friend, her sole witness at our courthouse wedding and her emergency contact on all her forms, and they talked on the phone every day in a mix of English and Vietnamese that I never did understand – but she shrugged at my question. I chuckled. ‘Just me, huh? I bet she tells you every bad thing about me.’ But again she shrugged and said, very innocently, ‘She don’t talk about you much, Bob.’ I’d long figured this much was true, but it burned to hear it acknowledged so casually. Suzy and I had been married for two years at the time. We somehow lasted six more years before she finally took off.

I sat in a front booth and finished off an extra large bowl of beef pho, four spring rolls, and two tall glasses of Vietnamese coffee, staring all the while at people passing by in the parking lot, including a bald Asian man who climbed into a red BMW. It could have been him, except Suzy’s new husband looked more bullish on his driver’s license and sported a thin mustache that accentuated the stubborn in his eyes. DPS listed a red BMW under his name – Sonny Van Nguyen – as well as a silver Porsche, a brand-new 2000 model. The master files at Vegas Metro confirmed he was fifty, five years older than me, and that he owned a posh sushi restaurant in town and an equally fancy rap sheet: one DUI, five speeding tickets, and three different arrests, one for unpaid speeding tickets, two on assault charges. He apparently struck a business associate in the head with a rotary phone during an argument and a year later threw a chair at someone in a casino for calling him a name. The last incident got him two years’ probation, which was four months from expiring. It was Happy who told me he was a gambler, fully equipped with a gambler’s penchant for risking everything but his pride. You should be afraid of him, Happy had said, but I knew it was already too late for that.

In my two decades on the Oakland force, I had punched a hooker for biting my hand, choked out a belligerent Bible salesman, and wrestled thugs twice my size and half my age. I once had a five-year-old boy nearly bleed to death as I nightsticked his mother, who had chopped off his hand with a cleaver, tweaked out of her mind; I’d fired my gun three times and shot two people, one in the thigh, the other in the palm, both of whom had shot at me and quite frankly deserved more; I’d been known to kick a tooth or two loose, bruise a face here and there, maybe even silently wish more harm than was necessary. But never, not once, had I truly wanted to kill anyone.

I walked down Spring Mountain Road and quickly regretted not taking my car. Vegas, beyond the Strip, is not a place for pedestrians, especially in the summer. I’d pictured a Chinatown similar to Oakland’s or San Francisco’s, but the Vegas Chinatown was nothing more than a bloated strip mall – three or four blocks of it painted red and yellow and then pagodified, a theme park like the rest of the city. Nearly every establishment was a restaurant, and the one I was looking for was called Fuji West. I found it easily enough in one of those strip malls – nestled, with its dark temple-like entrance, between an oriental art gallery and a two-story pet store. It was not set to open for another hour.

Nothing surprising about Vietnamese selling Japanese food. Happy’s uncle owned a cowboy clothing store in Oakland. What did startle me was the giant white-aproned Mexican – all seven feet of him – sweeping the patio, though you might as well have called it swinging a broom. He gazed down at me blankly when I asked for Sonny. He didn’t look dumb, just bored.

‘The owner,’ I repeated. ‘Is he here?’

‘His name’s no Sonny.’

‘Well, can I speak to him, whatever his name is?’

The Mexican, for some reason, handed me his broom and disappeared behind the two giant mahogany doors. A minute later a young Vietnamese man – late twenties, brightly groomed, dressed in a splendidly tailored tan suit and a precise pink tie – appeared in his place. He smiled at me, shook my hand tenderly. He relieved me of the broom and leaned it against one of the wooden pillars that flanked the patio.

‘How may I help you, sir?’ He held his hands behind his back and spoke with a slight accent, his tone as formal as if he’d ironed it.

‘I’d like to see Sonny.’

‘I’m sorry, no one by that name works here. Perhaps you are mistaken? There are many sushi restaurants around here. If you like, I can direct you.’

‘I was told he owns this restaurant.’

‘Then you are mistaken. I am the owner.’ He spoke like it was a friendly misunderstanding, but his eyes had strayed twice from mine: once to the parking lot, once to my waist.

‘I’m not mistaken,’ I replied and looked at him hard to see if he would flinch.

He did not. I was a head taller than him, my arms twice the size of his, but all I felt in his presence was my age. Even his hesitation seemed assured. He slowly smoothed out an eyebrow with one finger. ‘I am not sure what I can do for you, sir.’

‘How about this. I’ll come back this evening for some sushi. And if Sonny’s not too busy, he can join me for some tea. I just want to have a little chat. Please tell him that for me.’

I turned to go but felt a movement toward me. The young man was no longer smiling. There was no meanness yet in his face, but his words had become chiseled. ‘You are Officer Robert Ruen, aren’t you?’ he declared. When I didn’t answer, he leaned in closer: ‘You should not be here. If you do not understand why I am saying this, then please recognize my seriousness. Go back home and try to be happy.’

That last thing he said unexpectedly moved me. It was like he had patted my shoulder. I noticed how handsome he was – how, if he wanted to, he could’ve modeled magazine ads for cologne or expensive sunglasses. For a moment I might have doubted that he was dangerous at all. He nodded at me, a succinct little bow, then grabbed the broom and walked back through the heavy mahogany doors of the restaurant.

I felt tired again. Pho always made me sleepy. I walked back to the hotel and in my room stripped down to my boxers and cranked up the AC before falling back into bed.

People my age get certain feelings now and then, even if intuition was never our strong suit in youth, and my inkling about this Sonny guy was that he was the type of restaurant owner who, if he came by at all, would only do so at night, when the money was counted. My second inkling was that his dapper guard dog stayed on duty from open to close, and that he was willing to do anything to protect his boss. I had a long evening ahead of me. Before shutting my eyes, I decided to put my badge away, deep in the recesses of my suitcase.

When suzy left me, it was easy at first. No children. No possessions to split up. No one really to care. I was an only child, my parents both years in their graves, and her entire family was either also dead or still in Vietnam. After eight years together, I’d gotten to know maybe two or three of her friends, and the only things my police buddies knew about her was her name and her temper.

She gave me the news after Sunday dinner. I was sitting at the dining table, and she approached me from the kitchen, her mouth still swollen, and said, ‘I’m leaving tomorrow and I’m taking my clothes. You can have everything else.’ She carried away my half-empty plate and I heard it shatter in the sink.

The first time I met her, I knew she was fearless. I was responding to a robbery at the flower shop where she worked. She’d been in America almost a decade, but her English was still pretty bad. When I arrived, she stood at the door with a baseball bat in one hand and bloody pruning shears in the other. Before I could step out of the patrol car, she flew into a tirade about what had happened, as though I’d been the one who robbed her. I understood about a quarter of what she said – something about a gun and ruined roses – but I knew I liked her. That petite sprightly body. Her lips, her cheekbones: full and bold. Firecracker eyes that glared at people with the urgency of a lit fuse. We found the perp two miles away, limping and bleeding from a stab wound to his thigh. The pruning shears had done it. Suzy and I married four months later.

I was thirty-five then, an age when I once thought I should already have two or three kids, though I suspected she, at thirty-three, had given little thought to her own biology, let alone the passage of time. When I proposed, she agreed on the spot, but only if I was okay with not having children. She was not good with kids, she said, and having them would hurt too much, two reasons she repeated when I brought it up again a year later and a third time the year after that. I always figured she’d eventually change her mind.

Her real name was Hong, which meant ‘pink’ or ‘rose’ in Vietnamese. But it sounded a bit piggish the way Americans pronounced it, so I suggested the name of my first girlfriend in high school, and this she did give me, though her Vietnamese acquaintances still called her Hong.

When we married, neither of us seemed to have any worldly possessions beyond our clothes and the car we drove. It was like we had both, up until the time we met, lived our adulthoods at some cheap motel, so that we knew nothing about domesticated life beyond paying bills and doing laundry. We combined all our savings and bought an old townhouse near Chinatown that I repainted and she furnished – a luxury she’d apparently never had and one she indulged in with care and sincerity, down to the crucifixes that adorned every room and the two brass hooks on the wall of the entryway, the one for my coat a little higher than hers.

In our first year, we bonded over this novelty of owning a home, of living with another human being and building a brand-new life together with chairs and tables and dishes and bath towels. We were happy, I realize now, not because of what we actually had in common, but because we were fashioning this new life out of things that had never existed for either of us.

I’d stop by the flower shop every afternoon during my patrol to visit her. We had two days of the week together, and we spent it fixing up the townhouse, exploring local consignment shops, trying out every cheap restaurant in Chinatown, then going to the movies (Westerns and old black-and-white detective films were her favorites) or walking the waterfront, where the smell of the ocean reminded her of Vietnam. For a long time I didn’t mind losing myself in her world: the Vietnamese church, the food, the sappy ballads on the tape player, her handful of ‘friends’ who with the exception of Happy hardly spoke a lick of English, even the morbid altar in the corner of the living room with the gruesome crucifix and the candles and pictures of dead people she never talked about. That was all fine, even wonderful, because being with her was like discovering a new, unexpected person in myself.

But after two years, I realized she had no interest in discovering me: my job, my friends, my love for baseball or cars or a nice steak and potato dinner. She hardly ever asked me about my family or my upbringing. She must have assumed, because of her silence about herself, that I was equally indifferent to my own past. She didn’t know that until her I had not thought of Vietnam since 1973, when I was eighteen and the draft ended and saved me from the war, and that all of a sudden, decades later, this distant country – this vague alien idea from my youth – meant everything again, until she gradually embodied the place itself, the central mystery in my life. The least she could do was share her stories, like how happy her childhood had been and how the war upended everything, or what cruel assholes the Communists were, or how her uncle or father or neighbor had died in battle or survived a reeducation camp, or something. But she’d only say her life back home was ‘lonely’and‘uninteresting,’ her voice muted with hesitation, like she was teaching me her language and I’d never get it anyway.

Gradually, an easy distance settled between us. I found I loved her most when she was sick and had no choice but to let me take care of her. Feed her. Give her medicine. Keep her housebound, which she rarely was for more than a day. And since I’d apparently reached the limit of what she was willing to give me, I grew fond of any situation where she’d talk about herself, even if it was her waking in the night from a bad dream and then, in the grip of her fright, waking me too so I could lie there in the darkness and listen to her recount it.

She had bad dreams constantly. Recurring ones where I had cheated on her and hurt her in some profound way and she’s beating me with her fists as violently as she can and yet all I’m doing is laughing and laughing as she throttles me in the face. Sometimes it’s another man in this dream, though she’d never say who that might be – perhaps a lover from her past whose sins she was now mistaking for mine. Then there were the dreams where she’s murdered someone. Not just one person but a lot of people. She doesn’t murder them in the dream, she’s only conscious of having done it and must now figure out how to cover it up. In one version, she has buried them under piles of clothes in the closet. In another, she has shoved them into the washer, the dryer, that large cabinet in our laundry room where she kept all the strange pickled foods I could never force myself to like. And the entire time, all she can think about it is that she has killed people and that her life is now over.

I remember her describing one dream where she’s walking for hours through an empty furniture store and someone is following her as she makes her way across beautiful model bedrooms and kitchens and living rooms. Even as she climbs the stairwells from one floor of the store to the other, the person keeps following her, their footsteps loud and steady. I asked if she ever saw what the person looked like, and she said she couldn’t make herself stop or turn around in the dream, and that all she wanted was for the person to catch up to her, take her by the shoulder, and show their face.

To church every Sunday, she brought along a red leather-bound journal, worn and darkened with age, and held it in her lap throughout Mass like a private Bible, except she never opened it. She said it was a keepsake from the refugee camp and that it made her feel more right with God at church, whatever that meant. At home, it lay on the altar beneath the crucifix. I opened it once. The first few pages, brittle and yellowed, were written in someone else’s handwriting, the rest in Suzy’s tiny Vietnamese cursive, which was already hard to read. I tried translating the first page with a bilingual dictionary but could get no further than the opening sentence. Something about rain in the morning and someone’s mother yelling at them. Suzy once forgot the book at church and didn’t realize it until bedtime. She wanted to go right then and there to retrieve it, insisting, ‘Someone is always there!’ But I refused to let her go. At dawn the next morning, after a long, sleepless night, she drove to church and came home with the journal clutched to her chest like a talisman, her eyes red from crying. She did not speak to me the rest of the day.

She could go an entire week without speaking. A way at first to punish me for whatever I had done to anger her, though gradually, almost every time, her silence outlasted her anger and became a retreat from me and into herself, an absence actually, as though she had gotten lost in whatever world she had escaped into. Her temper – that flailing beast inside her that she herself hated – would retreat as well, and the only thing left between us until she spoke again was what we had said and done to each other when we fought: about money we didn’t have and the children we weren’t having, about what to eat for dinner, about my poor driving and my poor taste in clothes and a million other things I can’t remember anymore. I always played my part, stubborn and mouthy as I am, my own temper always burning brightest before hers exploded. She’d go from yelling at me to lunging at me, those eyes erupting out of her face as she slapped and punched my chest or seized my neck with both hands. Both of us knew she was not strong enough to hurt me, and on a certain level I think she went out of her way to avoid it, never throwing or breaking anything in the house, never once using anything but her hands and her words. Even as I held her wrists and let her scream at me, let her kick me in the stomach or the legs, it sometimes felt as though she were asking me – with her hateful, pleading eyes – to hold her back and tie her to the mast until the storm passed. Because inevitably she’d crumple to the floor and cry herself into a numb silence and eventually into bed, where she would begin withdrawing from me and the world.

Sometimes we didn’t need an argument. She’d be talkative and affectionate in the morning, and then I’d come home in the evening and she’d seem afflicted with some flu-like melancholy that only silence and aloneness could treat. So I learned to let her be. I turned on the TV in the kitchen during dinner. I turned up the music in the car as she sat staring out the window. I spent more and more time with friends at the bar or at our weekly poker game. I slept in our spare bedroom, which was otherwise never used.

Once or twice a year, I’d startle awake in the middle of the night and find myself alone in bed, the house empty, her car still parked in the driveway. An hour later the front door would open and she’d be barefoot in her nightgown and a jacket, having taken one of her nocturnal walks through the neighborhood, God knows what for or where to. She’d crawl back into bed without explaining anything, despite my stares and my questions, and in the morning I’d notice the dirty bottoms of her feet, the stench of cigarettes on her clothes, the whiff of alcohol on her breath. One evening I came home from work and every single light in the house was on, and she was out back beneath the apple tree, curled up and asleep on the grass, empty beer bottles lying beside her with crushed cigarettes inside.

Then, after a few days, sometimes as long as two weeks, without any hint whatsoever of reconciliation, she’d crawl into my arms while I lay on the couch watching TV, roll over in bed and bury her face in my chest, join me in the shower and lather me with soap from my head to my feet. I never knew how to feel in these moments, whether to love her back or commence my own week of silence. Not until she started talking again, recounting some funny incident at the flower shop two weeks before, or describing some movie she’d seen on TV at three in the morning, would I then feel her voice burrow into me, unravel all the knots, and bring us back to wherever we were before the silence began. Then we’d make love and she would whimper, a childlike thing a lot of Asian women do, except hers sounded more like a wounded animal’s, and that would remind me once again of all the other ways I felt myself a stranger in her presence, an intruder, right back to where we were.

And yet we still kept at it, year after year of living out our separate lives in the same home, of needing each other and not knowing why, of her looking at me as though I was some longtime lodger at the house, until I came to believe that she was both naive and practical about love, that she’d only ever loved me because I was a cop, because that was supposed to mean I’d never hurt her.

The night I hit her was a rainy night. I had come home from the scene of a shooting in Ghost Town in West Oakland, where a guy had tried robbing someone’s seventy-year-old grandmother and, when she fought back, shot her in the head. I was too spent to care about tracking mud across Suzy’s spotless kitchen floor, or to listen to her yell at me when she saw the mess. Couldn’t she understand that blood on a sidewalk is a world worse than mud on a tile floor? Shouldn’t she, coming from where she came, appreciate something like that? I told her to just fuck off. She glared at me, and then started with something she’d been doing the last few years whenever we argued: she spoke in Vietnamese. Not loudly or irrationally like she was venting her anger at me – but calmly and deliberately, as if I actually understood her, like she was daring me to understand her, flaunting all the nasty things she could be saying to me and knowing full well that it could have been gibberish for all I knew and that I could do nothing of the sort to her. I usually ignored her or walked away. But this time, after a minute of staring her down as she delivered whatever the hell she was saying, I slapped her across the face.

She yelped and clutched her cheek, her eyes aghast. But then her hand fell away and she was flinging indecipherable words at me again, more and more vicious the closer she got to my face, her voice rising each time I told her to shut up. So I slapped her a second time, harder, sent her bumping into the dining chair behind her.

I felt queasy even as something inside me untangled itself. There’d been pushing in the past, me seizing her by the arms, the cheeks. But I had never gone this far. The tips of my fingers stung.

Everything happened fast, but I still remember her turning back to me with her flushed cheeks and her wet outraged eyes, her chin raised defiantly, and how it reminded me of men I’d arrested who’d just hit their wives or girlfriends and that preternatural calm on their faces when I confronted them, the posturing ease of a liar, a control freak, a bully wearing his guilt like armor. It made me see myself in Suzy’s pathetic show of boldness. She’d never been as tough as I thought, and now I was the bad guy.

She spit out three words. She knew I understood. Fuck your mother. She said it again, then again and again, a bitter recitation. I barked at her to shut her mouth, shoving my face at hers, and that’s when she swung at me as if to slap me with her fist, two swift blows on my ear that felt like an explosion in my head. I put up an arm to shield myself and she flailed at it, still cursing me, until finally I backhanded her as hard as I could, felt the thud of my knuckles against her teeth.

She stumbled back a few steps, covering her mouth with one hand and steadying herself on the dining table with the other until she finally went down on a knee, her head bowed like she was about to vomit. Briefly, she peered up at me. Red milky eyes, childish all of a sudden, disbelieving. I watched her rise to her feet, still cradling her mouth, and shamble to the sink and spit into it several times. I watched her linger there, stooped over like she was staring down a well. I didn’t move – I couldn’t – until I heard her sniffling and saw her raise herself gingerly and reach for a towel and turn on the faucet.

As I walked upstairs, I listened to the water running in the kitchen and the murmuring TV in the living room and the rain pummeling the gutters outside, and everything had the sound of finality to it.