4,56 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WS

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

A fine collection of contemporary plays by one of South Africa's leading playwrights.

The plays selected, namely Into the Grey, Shooting and Swing cover topics such as social activism, the death of a friend and discrimination in sport. Described through Singh’s satirical lens, these thought-provoking plays bring us up to date with the challenges of life in post-Apartheid South Africa. They focus particularly on people of Indian origin and their relationships with other South African communities and chart the loss of ideals in the dream of the Rainbow nation.

Includes:

Into the Grey: A harrowing drama depicting the twenty-nine year association between two Durban activists who battle a variety of challenges as their country stumbles towards a bleak future.

Shooting: A one-man play about the unchanging paradigm in Durban’s small town communities in the early years of democracy as a football prodigy’s dream is brutally shattered.

Swing: A two-hander about the relationship between a mixed-race Durban tennis player and her father/coach as they confront many obstacles in a society which undervalues the girl-child.

With a foreword by director Ralph Lawson and introduction by Pranav Joshipura, Associate Professor of English, Mahila College, Gandhinagar, India.

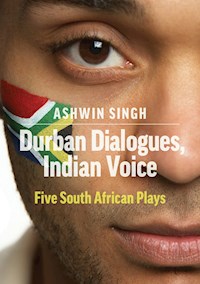

A follow-up anthology of three hard-hitting plays to Singh’s successful drama anthology Durban Dialogues, Indian Voice (2013) which is now studied internationally.

“Ashwin Singh’s plays, working in a contemporary idiom and style and context, become a place for us to set up house, to inhabit, a place filled with humour, compassion and insight. They categorically signal a disposition not to remain silent, not to remain indifferent, prompting us and nudging us to make choices about how we live in our world.” Dr Betty Govinden, KZN Literary Tourism

“The ability to capture the lives and communities of Durban with both pathos and humour resonates in all Singh’s works. The plays pay tribute to the city’s cultural and aesthetic beauty but they also expose its underbelly of crime, corruption and racial tension.” Estelle Sinkins, Weekend Witness

“As with his To House and Spice ‘n Stuff, Shooting author Ashwin Singh tackles his subjects head-on, using his considerable writing skills to blend important historical and contemporary issues with entertainment.” Caroline Smart, The Mercury

About the author

Ashwin Singh is an attorney, academic, playwright, director and actor. His first anthology of plays, Durban Dialogues, Indian Voice was published in 2013 by Aurora Metro Books. The book is being studied and/or referenced at a variety of universities in South Africa, India, Canada and Europe. Singh has also been published as a playwright in the collective anthologies, New South African Plays (Aurora Metro Books, 2006) and the Catalina Collection (Catalina UnLtd, 2013). He is also a published poet and academic author.

Singh is a three-time national award winner via the PANSA Playreading Festival (the country’s foremost playwriting contest) with his plays To House (2003); Duped (2005); and Reoca Light (2012). He is also a respected stage and radio actor, having performed in a number of dramatic and comic productions.

Singh also played a lead role in award winning UK director James Brown’s short film about child abuse, One Wedding and a Funeral.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 218

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2017

Ähnliche

Ashwin Singh

Ashwin Singh is an attorney, academic, playwright, director and actor. His first anthology of plays, Durban Dialogues, Indian Voice was published in 2013 by Aurora Metro Books. The book is being studied and/or referenced at a variety of universities in South Africa, India, Canada and Europe. Singh has also been published as a playwright in the collective anthologies, New South African Plays (Aurora Metro Books, 2006) and the Catalina Collection (Catalina UnLtd, 2013.) He is also a published poet and academic author.

Singh is a three-time national award winner via the PANSA Playreading Festival (the country’s foremost playwriting contest) with his plays To House (2003); Duped (2005); and Reoca Light (2012). He is also a respected stage and radio actor, having performed in a number of dramatic and comic productions. The stage productions include Spice ’n Stuff, Marital Blitz, PopCom, Culture Clash and To House. The radio productions include Psycho-Art, Switch Hitch and GrandAsia Lodge. His plays Spice ’n Stuff and To House have been adapted for radio on Lotus FM and SAFM respectively. Singh also played a lead role in award-winning UK director James Brown’s short film about child abuse, One Wedding and a Funeral.

Singh is a former board member of the Catalina UnLtd Theatre Company and is a script writing and business mentor for the Playhouse Company’s development programmes. The Singh Siblings (formerly AshTal Art), the Playhouse Company and Catalina UnLtd have been the most prominent producers of Singh’s works.

First published in the UK in 2017 by Aurora Metro Publications Ltd.

67 Grove Avenue, Twickenham, TW1 4HX

Foreword copyright © 2017 Ralph Lawson

Preface copyright © 2017 Pranav Joshipura

Summary and Analysis copyright © 2017 Shantal Singh

Into the Grey copyright © 2017 Ashwin Singh

Shooting copyright © 2009 Ashwin Singh

Swing copyright © 2015 Ashwin Singh

Production: Simon Smith

With thanks to: Anthony Crick, Ellen Cheshire, Marina Tuffier and Peter Fullagar.

All rights are strictly reserved. For rights enquiries including performing rights contact the publisher: [email protected]

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

This paperback is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBNs

978-1-911501-93-0 (print)

978-1-911501-94-7 (ebook)

Durban Dialogues,Then and Now

Ashwin Singh

Acknowledgements

I want to express my sincere gratitude to the following people, who have had such a profound influence on my artistic journey:

My sister, Shantal; my late father, Harry; my mother, Shunitha; Thayalan Reddy; Dolly Reddy; Betty Govinden; Lesley Jacob; Priya Narismulu; Zaakir Ally; Pranav Joshipura; Ralph Lawson; Linda Bukhosini; Themi Venturas; Derosha Moodley; Deborah Lutge; Lee-Anne Naicker; Kogi Singh; Habi Singh; B.P. Singh; Geno Moodley and the Moodley family; Pushpa Gramanie; Mariam Natalwalla; Pallavi Rastogi; Edmund Mhlongo; Rory Booth; Rowin Munsamy; Jenny Haslett; Ansuyah Moodley; Logan Perumal; Rubeshan Perumal; Renos Spanoudes; Chantal Snyman; William Charleton-Perkins; Clinton Marius; Charlene Moodley-Bezuidenhout; Sheeda Kalideen; Krishni Naidoo; the late Nirej Mothilal.

Foreword

It is seldom that one encounters a colleague whose aims and objectives mirror one’s own as clearly and with such complimentary precision as Ashwin Singh’s and mine. We first encountered one another a number of years ago as co-facilitators in The Playhouse Company’s Community Arts Mentorship Programme and soon discovered that our common interests extended beyond the cut and thrust of training and development in theatre making; indeed, we were quick to find ourselves in agreement that, while the mentorship of aspiring young performers and the incubation of new playwrights is vital to the future of the arts in our country, first-rate movies, fine Indian food and, in moderation, good red wine are equally important cornerstones of civilized existence.

First and foremost, though, it was Ashwin’s unique ability as a playwright that caught my attention. My quest, as an actor and director of close-on fifty years’ experience, for a current brand of theatre which addressed – succinctly, tastefully and coherently – issues pertinent to our lives as South Africans ended when he gave me To House to read. (This work features in his first anthology of plays.) Others followed, each a treasure trove of nuance and a moving evocation of aspects of life in current day South Africa. Earlier this year, I had the rare privilege of directing his one-person play, Reoca Light. This richly entertaining portrait of life in the predominantly Indian township of Reoca is revisited in Shooting when the young lawyer, Jehan Singh, arrives in his little hometown from Johannesburg for the funeral of his cousin and, as narrator, relates the comic and tragic stories of his youth. In Swing, the characters of Samantha, a talented mixed-race tennis player from Greenwood Park and Ram, her father, portray the host of colourful individuals which populate their lives. This look at the multi-dimensional challenges of being a Black sportswoman in a country which continues to be deeply divided has an emotional resonance that is tangible. Into the Grey, the most recent work in this anthology, introduces us to a world that is less cosy; again, the playwright has chosen a multi-cultural setting to examine, over a period of three decades, the relationship between two powerful activists who once shared a dream but whose world is now spiralling out of control as the values of their original struggles are compromised and apathy has become entrenched.

In Act II, Scene 2 of Hamlet, Shakespeare reminds us that the actors and their plays are “… the abstract (meaning ‘summary’) and brief chronicles of the time.” To my mind, Ashwin Singh’s plays do not merely chronicle our lives as South Africans in the twenty-first century; his skills as a dramatist are such that audiences and readers alike will experience, first hand, the very essence of the nature of his characters in a kaleidoscope of situations – colourful, moving, sometimes outlandish, often richly humorous and always thought-provoking.

Ralph Lawson

Actor, Playwright and Director

Preface

Award-winning playwright, director, actor and academic Ashwin Singh’s second anthology of three plays titled Durban Dialogues, Then and Now portrays South Africa at the end of its honeymoon period, where people seem to be disillusioned about the hope and promise that the rainbow nation offered at the beginning of their hard-earned democracy. By now, colour warfare has actually turned into class warfare, leading to an urgent need to redefine the terms ‘black’ and ‘white’. Issues like unemployment, crime, drugs, rape and disruptive forces from within and outside the nation are pressing ones, to which the government does not seem to pay adequate attention! Political leaders of the country seem to be conveniently ignoring the vision of Nelson Mandela and others to serve their petty interests. It appears as if the country is heading into a chaotic situation where the ideals of the rainbow existence and harmonious living of all races together could very rapidly vanish away.

Ashwin Singh presents such reality very honestly through three plays: Into the Grey, Shooting and Swing. His plays happen in an imaginary space, Reoca, as well as in the real physical spaces of Greenwood Park and Chatsworth, allowing his imaginary space to develop in the real theatrical space called life. The removal of Apartheid has allowed races to live freely neighbouring each other but unfortunately that seems to have failed to create cultural synthesis among them. Instead of celebrating diversity, the people presented here seem to have become shallow and don’t seem to care for one another. The Indian community presented in these plays is very different from those presented in Reoca Light in terms of their commitment to life and society. However, characters like Dr. Logan Pillay, Advocate Sandile Ndlovu, Anil Maharaj, Jehan and Ishaan Singh, Samantha and Ram, and Lerato Sibisi appear to be real-life individuals whom we might encounter every day.

Durban Dialogues, Then and Now charts progress from where the playwright leaves his argument in Durban Dialogues, Indian Voice. This is what demonstrates the maturity of the playwright. Ashwin Singh is not merely a Durban-based South African Indian playwright, he is a South African playwright representing the reality he sees and experiences in his daily life. The stories narrated from the Indian community perspective provide alternative points of view to the mainstream literature. Reoca, Greenwood Park and Chatsworth are microcosms of events happening in South Africa.

For someone sitting far away from South Africa, Durban Dialogues, Then and Now allows a peep into the contemporary South African situation mirroring literature to the society. In this context, Ashwin Singh emerges as a cultural ambassador reflecting his times artistically and faithfully. He is quite conscious of his responsibility. As a thinker and social activist, the playwright seems to be unhappy with the national policy makers and at times even feels dejected, but as in most of his plays, he is hopeful for a better tomorrow. In this sense, Ashwin Singh does not merely remain an armchair thinker in presenting the problems of his nation, rather he is like Dr. Logan Pillay and Advocate Sandile Ndlovu (Into the Grey) who never lose hope despite knowing that the nation is suffering from terrible diseases, and he indulges himself in artistic protest for a better tomorrow.

Pranav Joshipura

Associate Professor of English

Uma Arts & Nathiba

Commerce, Mahila College

Gandhinagar, India

Contents

Foreword

by Ralph Lawson

Preface

by Pranav Joshipura

Summary and Analysis

by Shantal Singh

The Plays

Into the Grey (2017)

Shooting (2009)

Swing (2015)

Summary and Analysis

Durban Dialogues, Then and Now is a second anthology of plays by Ashwin Singh. It examines the transitional lives of South Africans as they attempt to dismantle the legacy of Apartheid and interrogate the unfulfilled and sometimes idealistic promises of a maturing democracy.

In Ashwin’s first anthology of plays, Durban Dialogues, Indian Voice he examines several different social themes: the evolving culture of multi-racial communities as they negotiate living in sectional title schemes and the politics of their work spaces (To House); a satire set on an airship which examines the socio-political foibles of a society jostling for power (Duped); the last days of hawkers and shopkeepers in Grey Street as people turn to shopping in malls more frequently (Spice ’n Stuff); a one-man comedy-drama which chronicles the inspiring stories of unsung heroes living in a small town (Reoca Light); and a day in the life of three Black women who either live or work in a formerly White suburb (Beyond the Big Bangs). Durban Dialogues, Then and Now features three further plays by Ashwin, namely Into the Grey, Shooting and Swing. The two anthologies obviously share similar geo-political realities and overarching thematic explorations but are quite different in the plot devices, tone, character construction and storylines.

Into the Grey takes the reader on a twenty-nine year journey of the bisecting lives of its two central characters. When we first meet Logan Pillay it is in his capacity as an activist. He is offering recollections of past incidents of violence and social insights to a crowd that has gathered at a recently burned beloved community building. The reader is immediately placed in the reality that our social ills are assuming cyclical patterns, which is a sobering reality for South Africans in our current tumultuous political climate. Logan’s introduction to Sandile Ndlovu is as fellow students who have been arrested during protest action on campus. Their initial scepticism of each other turns to friendship and respect for their role as activists and skilled professionals until they become socially disengaged when they focus on individual professional pursuits. Logan becomes a specialist obstetrician and Sandile, who is an advocate, pursues a career in politics.

Lurking through the play is the constant uncertainties they face as they negotiate the many ‘greys’ that constitute the personal and professional challenges they experience. The choices in their lives no longer resemble the clarity of polarized views but instead have a multiplicity of realities. Individual needs are challenged by organizational requirements, long working hours take precedence over personal lives and result in fatigued and murky decisions as well as poor service delivery. Sandile admits: “I’m living in the dirty grey now, Logan.” In that instance he is admitting his failing and then he asks for forgiveness. However, his own redemption is a journey of uncertainty that he initiates, and in so doing develops a more secure sense of self-worth. Logan similarly takes ownership of his own mistakes later in his life and reveals his sentiments that he is ‘dying in the dirty grey’.

Into the Grey gives us snapshots into the lives of the characters and through it we learn about their conflicts, chaos and choices. The play serves as a mirror to our nation’s political portraits, much of which leaves the reader pulsating with emotions. However, as in most of Ashwin’s works there is the element of hope that the ‘grey’ that we are entering is offering us the opportunity to explore uncertainty with the assurance that we can understand ourselves better than before and hopefully engage in nation building.

Shooting is a harrowing one-man play about a football prodigy, Ishaan Singh who never gets to realise his dream and is murdered as a young adult. The story is told through the eyes of his cousin Jehan Singh, a young lawyer who has come from Johannesburg to their home town Reoca to attend the funeral and deal with his cousin’s personal effects. As he sifts through the belongings of his cousin he unpacks their shared history as children and recalls their joy of playing sport together. He also reveals that the emotional and physical abuse suffered by Ishaan at the hands of his family as well as a lack of institutional support shattered the young man’s dreams. Shooting is a memory play and requires skilled writing to maintain the narrator’s anguish in dealing with the trauma of losing his cousin while recollecting past traumas and not dematerialising into sentimentality. It is also a delicate balance in engaging the reader’s feelings as one shifts from emotional distress to celebrating joyful memories of Jehan and Ishaan playing sport innocently in their backyard and thrilling the neighbourhood.

Ashwin constructs recollections reflective of a muddled mind filled with emotional turmoil but seeking to explore a better understanding of a childhood that is forever lost for both Jehan and Ishaan. Through the review Ashwin grounds Jehan in the house which he had occupied as a child and which Ishaan came to live in during the last days of his adulthood. The shared space affords Jehan the opportunity to reconnect spiritually with Ishaan while allowing him to keep the current and past interferences from the outside at bay. Jehan is no longer engaging in his childhood practice of ‘shooting’ which is an Indian colloquialism used to describe a person being prone to adopting a colourful retelling of a story. Instead the shooting of his cousin has brought a sobering realisation that Ishaan and he had barely connected in recent years and that there were several unanswered questions about his cousin’s life. Ultimately, Jehan is offered release from his feeling that he failed Ishaan when he is able to freely remember the many occasions they enjoyed shooting goals in the backyard. By doing this Jehan is able to reconcile the contradictory nature of the people who inhabited his childhood memories and to give Ishaan the acknowledgement that he never truly got in life.

Shooting unashamedly presents the poor Indian South African family, a reality which is seldom acknowledged in our country. Jehan recalls the sacrifices that his mother had to make so that she could meet financial demands. He goes on further to comment: “I still watch mothers in grocery stores. Trying to get the best for their children. And often putting the products back on the shelf.” This brings to the fore the reality that democratic South Africa did not bring social and economic uplift for many communities across racial barriers. The fortitude of the play is when the failings of individuals within those communities is highlighted as being the ultimate betrayal of the children who reside there. This is demonstrated by abusive and neglectful parents, a drug dealer peddling his goods and a rich businessman making false promises to develop the neighbourhood.

Swing is Ashwin’s first two-hander and has as its two central characters Samantha, a mixed-race tennis player and clinical psychology graduate from Greenwood Park and her father Ram who is her coach and mentor. Mr Rajpaul, a journalist we first learn about in Reoca Light, has asked the father/daughter team to reveal to him Samantha’s journey in achieving success in the tennis arena and the details of the rivalry between Samantha and Lerato Sibisi, a South African tennis champion. Samantha has an excellent support base who invest in her emotionally and make financial sacrifices to assist her to develop her tennis skills. Samantha and Ram share a deep love of sport and have each used it to tame the bullies in their lives and to unite their extended family. The play is a celebration of the adoration a father and daughter have for each other and through the interview with the reporter they challenge many previously held misperceptions. In a society that seldom acknowledges the girl child it is refreshing to have a father profess with joy the boundless opportunities that his daughter could have. While he is cradling her soon after her birth he proclaims: “You will not play second fiddle to any boy… and to any man.”

Swing also challenges the commonly accepted notion that the world should only acknowledge winners. The concept of being a winner as a nation has even invaded the rhetoric of international politics. Samantha has excelled in her academic studies but appears to play second fiddle to Lerato in tennis tournaments. Samantha questions whether “Lerato is obsessed with winning… pursuing the American dream rather than being guided by African ideals.” Lerato comes from a poor background and was fortunate to receive a tennis scholarship to a Californian university where she was able to develop her talent further. She is the admired athlete and Ram questions whether there is a “hierarchy of Blackness” when Lerato’s race is over-emphasised by a commentator. He believes it is a disservice to Lerato as it reduces her to being purely a race representative and it also fails to acknowledge other previously disadvantaged communities. Despite a progressive constitution South Africa remains a society divided on race, culture and class issues. Samantha’s parents’ interracial relationship which at that time was illegal serves as a reminder that we can set aside our prejudices. Samantha’s existence and the values that she exhibits suggest that there is hope for the future of the nation.

The use of the double narrator to play all the roles in Swing is intriguing. It allows for creative storytelling and enables a cathartic process to occur as the narrators role-play the personas of the people who occupy spaces in their story. It also uses an artistic device of the single player when they engage in monologues and the doubles players when they share aspects of the story together, which are positions that would be occupied in the two forms of the sport of tennis.

Durban Dialogues, Then and Now is an honest and engaging collection of plays. Like with all of Ashwin’s works he is comfortable presenting the contradictions of his characters as they negotiate their socio-political realities. He is able to accurately encapsulate the stories of people from a different gender, race and culture to his own and to give a voice to the marginalised people of South Africa.

Shantal Singh

Clinical Psychologist

Theatre Producer and Director

INTO THE GREY

Setting

Durban, largely the township of Chatsworth.

The Players

Main Characters

Logan Pillay

(21, 26, 32, 43, 50)

A doctor and activist

Sandile Ndlovu

(27, 33, 44, 51)

A lawyer and activist

Supporting Characters

Sgt Moodley

(35)

A policeman

Anil Maharaj

(41, 42, 59)

A successful entrepreneur

Vinesh Maharaj

(21)

His son

Robbie Philander

(32)

A male nurse

Set Design

The action of the play occurs in different parts of Chatsworth and the Durban CBD: a youth centre; a university courtyard; a public hospital; and a Chatsworth street. A realistic set design would involve an intricate process and may interfere with the rapid flow of the play as it moves through different eras. An expressionist design is recommended. A painted backdrop of a rainbow with a pot of gold at one end and a melting pot of South African cultures at the other end is suggested. Below the rainbow, a few miniature huts and RDP houses could be constructed with a couple of high-rise buildings placed behind these to illustrate the stark aesthetic and economic contrasts of contemporary South Africa.

The following would also be required: a couple of black boxes for the speakers at the youth centre to use; a street pole at the university courtyard; a desk and swivel armchair; a small table and two chairs; and a street bench. The different spaces could be further populated utilising a variety of design options. This is unnecessary in an expressionist design unless it has significant symbolic value and is left to the discretion of the designer and director.

1. Free-Dome Tomorrow

Lights come up on Logan. He is standing on a box in the space that represents The Dome, a nightclub in Chatsworth which was recently destroyed in a fire. He is addressing a small audience of adolescents and young adults.

“Run,” my cousin Bivash shouted. And then he shoved me forward and began sprinting. So I ran. And they chased us. The young African men who had come to burn Bivash’s house in Inanda… because they had been manipulated into believing that these Indians had taken their land… when in fact it had been designated for the Brown man by the Apartheid government and they had nowhere else to go. And now these Indians had built pretty white houses on property that was once their African ancestors and should’ve held their pretty white houses. And some of these Indians were thriving now… running successful businesses and exploiting Black labour… a few even drove silver BMWs with tri-star mag wheels.

And then I turned around in terror as they drew nearer to us… and I recognised one of them… it was Sihle… our friend Sihle, with whom Bivash and I had played hours of football every time I stayed over during the summer holidays. He looked so angry. He shouted something menacing in isiZulu. And then just as they were about to tear our flesh with their batons and pangas, my uncle Suresh’s van appeared and we threw ourselves into the back… and escaped. But they burnt Bivash’s house down that day… and many more over the next few days. (Pause) I can see that some of you are getting restless already. Just let me finish the story please… you’ll see why I’m telling it shortly.

Anyway… many of the Indians of Inanda, including my relatives, were forced to move in with family and friends in Duffs Road and other neighbouring Indian districts. And as the terror threatened to spread, these districts began organising themselves… and preparing to take revenge. It didn’t matter which Black man they found loitering in the neighbourhood… “All darkies are dangerous now,” they said. (Pause) The stories I heard… gardeners, hawkers, factory workers… so many innocent Black men just going about their business in the districts… humiliated and assaulted. And then one day when we were visiting our relatives in Duffs Road, I saw them grab Bongani… the petrol attendant they had known for a decade… he had supplied the invaders with information they said… he was planning more attacks. “Chop his head! Hold him and I’ll take it out” I couldn’t believe it. It was my father… who had never committed an act of violence in his life… now he was thirsting for blood! And then just as he raised his bush knife, my uncle Suresh flung himself in front of Bongani. My uncle… whose arm they had broken… whose house they had burnt… pleaded for mercy. “We can’t sink so low… we’re better than this,” he said. “This man is innocent. I don’t know who’s guilty… and of what they may be guilty exactly. But we have to find another way to get justice. There’s a bigger struggle… and we are part of that.” (Pause) I’ll never forget those words that my uncle spoke. On the 22nd of May 1984. My matric year. (Pause) The violence stopped completely soon after that… from both sides… but relations between the two communities were obviously damaged. “This is just like 1949,” many people said. “We’ll never really be united again.” I didn’t believe their words. I believed what my uncle had said. (Pause)

But that was four years ago. And it wasn’t in our town. So why am I telling you about it today? Because something very similar happened here in Chatsworth three weeks ago. Starting with another fire… this time, right here in your favourite hangout – The Dome. And we began running again… after a Black boy we blamed for the fire… but he didn’t cause the fire… we did. (Pause)

I remember running after that mob… who were chasing after Bheki… and the image of my father swinging that bush knife came into my head… and I heard my uncle’s words again. I shouted for the mob to stop… but they wouldn’t listen. It was happening again. (Pause)