Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

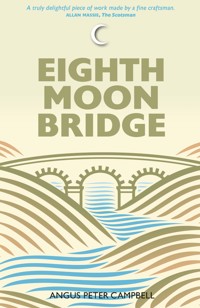

'They say he brought back some Spanish gold and others say he didn't bring anything except the rags he was wearing but had the power to turn stone into gold and that the two stories somehow got mixed up.' Did Olghair MacKenzie steal alchemical secrets from the Egyptians? Or was he a rebel pirate who found refuge on a small Scottish island after the Armada? Does his treasure still lie hidden there? Six hundred years after MacKenzie's death, an ex-footballer returns to the island where he spent his youth. As the first frosts of winter arrive, Jack moves into a fisherman's cottage fragrant with the scent of the sea. After many restless years, it is a true homecoming. Delighting in his employment as postie, he starts to reconnect with himself, with his family and with this tiny community. The tale of Olghair MacKenzie has fascinated Jack since childhood and he resolves to discover the truth behind the legend. To do so, he must unlock the secret of a bridge the shape of a perfect wave, understand the significance of stone number 759 and find out what is meant by the eighth moon. Can Jack trust the dreams of the local seer, or grasp the clue in the old Gaelic way of counting the months? Jack's quest is truly magical, for it will lead him into very personal territory, unveiling links that tied him to the island long before he ever set foot there.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 180

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ANGUS PETER CAMPBELL is a native of the Island of South Uist in the Outer Hebrides and was brought up there and on the Island of Seil in Argyll. His writing has won many awards over the years, including the premier Bardic Crown from the leading Gaelic organisation, An Comunn Gàidhealach. His Gaelic novel An Oidhche Mus do Sheòl Sinn was voted by the public into the Top Ten of the Best-Ever novels from Scotland. His poetry collection The Greatest Gift was reviewed as a masterpiece by Sorley MacLean, his poetry collection Aibisidh won the Scottish Poetry Book of the Year Award in 2012, and his novel Memory and Straw the Scottish Fiction Book of the Year Award in 2017. The writer, academic and singer Dr Anne Lorne Gillies has described him as ‘an international literary figure alongside the likes of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Toni Morrison and Laura Esquivel’.

By the same author:

The Greatest Gift, Fountain Publishing, 1992

Cairteal gu Meadhan-Latha, Acair Publishing, 1992

One Road, Fountain Publishing, 1994

Gealach an Abachaidh, Acair Publishing, 1998

Motair-baidhsagal agus Sgàthan, Acair Publishing, 2000

Lagan A’ Bhàigh, Acair Publishing, 2002

An Siopsaidh agus an t-Aingeal, Acair Publishing, 2002

An Oidhche Mus Do Sheòl Sinn, Clàr Publishing, 2003

Là a’ Dèanamh Sgèil Do Là, Clàr Publishing, 2004

Invisible Islands, Otago Publishing, 2006

An Taigh-Samhraidh, Clàr Publishing, 2007

Meas air Chrannaibh/Fruit on Branches, Acair Publishing, 2007

Tilleadh Dhachaigh, Clàr Publishing, 2009

Suas gu Deas, Islands Book Trust, 2009

Archie and the North Wind, Luath Press, 2010

Aibisidh, Polygon, 2011

An t-Eilean: Taking a Line for a Walk, Islands Book Trust, 2012

Fuaran Ceann an t-Saoghail, Clàr Publishing, 2012

The Girl on the Ferryboat, Luath Press, 2013

An Nighean air an Aiseag, Luath Press, 2013

Memory and Straw, Luath Press, 2017

Stèisean, Luath Press, 2018

Constabal Murdo, Luath Press, 2018

Tuathanas nan Creutairean, Luath Press, 2021

Constabal Murdo 2: Murdo ann am Marseille, Luath Press, 2022

Electricity, Luath Press, 2023

Thanks to Andrew Kydd who inspired the making of this story.

First published 2024

ISBN: 978-1-80425-178-2

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon by

Main Point Books, Edinburgh

© Angus Peter Campbell 2024

Contents

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Acknowledgements

1

I’M NOT EVEN sure it was an island, though everyone called it The Island. Of course, before the bridge was built it would have been, though there were some arguments over that too. Hadn’t the ancient tribes placed shoogly stones in the water so they could go across at low tide, and hear the stones moving when strangers – enemies – came calling? And didn’t the Romans build a stone path for their chariots, which the Vikings then destroyed because what need did they have for solid roads when the seas and the oceans and the lochs and rivers were their highways?

But the bridge is modern. Relatively new, anyway. Built by General Wade to garrison his troops in the old castle, but – more importantly – to open up the island to trade and commerce with the mainland. So the islanders would not be so insular and clannish and suspicious and bloody-minded, but would learn that the mainland merchants posed no danger to them. Dissolute mainlanders who had no strength because they didn’t eat enough fish and wore thin, useless clothing. Who carried no swords or flames of fire. They just wanted to make a bit of money and sell shoes and horses and nails to the islanders. And the mainland wives and women and girls could be as charming and able to bear as many heavy loads of peats on their backs, and as many children, as the island women. It’s a pretty, arched bridge. They say the rebel pirate Olghair MacKenzie hid his priceless Spanish treasure in it after the Armada, but only children and old people believed that story.

All that’s history. For the bridge now carries an endless stream of traffic across, day and night. The early morning school bus, and the forestry van and the fish-farm lorry and all the individual cars taking hotel and office and road workers into the nearest large town, and the bread van and the fish van and the library van and the coal lorry coming over the other way bringing sliced bread and filleted haddock and books and trebles to the island, and – of course – all the visitors and tourists coming over the bridge for the day, just to see what The Island is like. Is it as pretty as it looks in the pictures?

It’s bare and rocky on the north, towards the open sea. And green and lush on the south side, where the bridge and the firth and all the gardens are, smelling of lilac and wild garlic and buddleias. That’s where we came to stay.

My father was the schoolmaster. We’d always lived in the city, but this job came up. I didn’t know anything about it until the whole deal was done and Dad announced to me one night after supper that we’d be leaving and going north in a month’s time. North. There would probably be snow and lots of ice and we might even live in an igloo and wear furs and sealskins to bed, as in the books. Though it was never that far north. Just a hundred miles up the road.

‘It’s like Treasure Island,’ he said to me. ‘Loads of caves and coves and rocks and hills and hiding places.’

‘And pirates?’ I asked.

He laughed.

‘Not unless you and I become one!’

I don’t think Mum wanted to go. As I sat in my bedroom upstairs, reading, I could hear their voices. Dad calm and measured, in that quiet voice which I knew annoyed Mum so much. I heard her once saying,

‘Why don’t you speak normal? If you’re angry, just speak in an angry voice rather than in that sweet, puddingy way.’

I thought it was funny. But that was the voice he was now using, and though I couldn’t hear what Mum was saying I knew by her higher pitch that she was annoyed. ‘Shop,’ I heard her say, and ‘flowers’, but then Dad’s soft, reasoned voice resumed again, then there was silence.

We arrived on The Island in early summer. Mum made all the arrangements, because she was the one who did that kind of work. I helped her a bit, putting books into boxes and cutlery and pictures and ornaments into crates and labelling them.

Especially labelling them, because I was good at writing and I liked using the non-smudge pens. Magazines, I wrote on one box. And Gardening Books on another. And Cooking. Knives. Forks. Spoons. Plates. Pots. Careful DO NOT SHAKE I wrote on the big box with Mum’s three small Delftware vases, well wrapped between tea towels and protected by brown wrapping paper. And they survived, taking pride of place on the dresser in the living room of our new home.

I was ten and just finishing Primary Six. Dad said he would have preferred to have moved a year later, when I finished Primary Seven. That would have been a cleaner break for me, without having to change from one primary school to another. But really he had little choice, because the job advert was one of those once-in-a-lifetime opportunities he didn’t want to miss. It was unlikely to happen again.

Term time finished on a Friday, so we moved the first weekend of the summer holidays. The removal men came in the morning while I was still at school and when I came back home at three o’ clock everything was already inside the van. It was strange seeing the house empty, except for the things we couldn’t take: the bath and fireplace and flooring and kitchen units. I could see all the scratches and marks and dust and drawings on the walls, no longer hidden by tables and chairs and dressers and cupboards.

My crayon drawing of a dinosaur with fifteen legs and bright orange scales decorated the wall where the mirror had been, and the pencil marks of me growing bigger every birthday stretched up the window frame. I stood by the marks and was already taller than I had been on my last birthday. I was a bit sad that I couldn’t add to it. Though the new people would probably paint over it anyway. And I would make new marks at the new house and see how high they would go.

Mum and I got a lift up to The Island in the removal van. It was amazing being so high up in the front of the lorry. We only had a small car, and I always sat in the back looking out at the traffic or playing some kind of game to pass the time. Green car blue car was one of my favourites, and the other one was counting the numbers on the buses that passed and adding all the numbers up to see if I could reach a thousand before we arrived at our destination. I never did, unless we drove out into the country and met a 916 or a couple of 502s.

But high up in the removal lorry I could see everything. The cars down below were like toys, and as soon as we left the city I could see for miles and miles across the fields and over the lochs and up into the sky where jet clouds crossed and passed each other. I sat between the driver and Mum, so I could watch him control the gears and the big driving wheel and the row of lights. He showed me how they changed from white to blue to orange at the flick of a switch.

‘Orange when it’s foggy,’ he said, ‘and blue when it’s frosty.’

The most fun I had was listening to the sound the lorry made as we drove up past Loch Lomond and over the hills. It had eight big wheels and every time they hit a hole or bump in the road it made us all bounce up and down. Same as the time Dad had taken me to the Fair and we sat together on the horse that went round and round the carousel. Dad sat behind me, holding my waist, and we shrieked and laughed every time the horse galloped up and down while the man who operated it turned the big green and yellow wheel.

‘This lorry has six gears,’ the driver said. ‘And they’re all animals!’ We were stopped at lights.

‘See,’ he said. ‘When the lights turn green I’ll put it into first gear. And that’s a bear! Hear – deep and growly.’

And as the lorry moved he pushed it into second gear.

‘A tiger,’ he said.

Then third.

‘Sounds like a lion,’ I said.

Fourth was a leopard and fifth a panther. We leapt along the road, rivers tumbling on one side and the hills getting higher and higher as we climbed up into the Highlands. Everything was connected to everything else and could become something new, I thought. Otherwise how could all those rivers turn into big lochs and the lorry into all those magic animals? You could invent anything.

Our new house was next to the school, 1889 carved on it above the main door. It had a long hallway and stairs with two bedrooms at the top, one mine and the other kept for visitors. Mum and Dad’s bedroom was downstairs at the back overlooking the garden. We had two big sitting rooms downstairs at the front, one where we all sat together to watch television and the other a ‘best room’ which we only used at Christmas or if some kind of special person like the minister or the school inspector came visiting. Then Dad lit the open fire and brought in the pine logs he kept in the shed to create the smell of Christmas for our guests.

I didn’t do much of the moving in. Just carried some of my clothes and books and my train set upstairs to my bedroom, and that was more or less it. The removal men did the rest, with Mum supervising and Dad shifting bits of furniture from here to there. He would position a chair in the corner, then stand looking at it for a moment, humming and hawing, then move it a few inches this way or that. Same with all the pictures. Mum dealt with the bedrooms and the kitchen, putting everything in order.

Once we settled into the house, Dad started to get up very early most Saturday mornings and head off with his rucksack, and sometimes his tent, to go walking for the day. To get away from the stress of being surrounded by noisy children all week, he said. He’d come back late in the evening but sometimes did it the other way round, heading off after school on Friday and returning back home Saturday morning. Teaching was just a public obligation compared to this private joy.

‘Can I come, Dad?’ I asked, but he always said No.

‘No, son. Not now. It’s the only time I get space to myself. To do a few things on my own. You’ll understand when you’re older, Jack.’

I sat upstairs in the window seat looking at the sea. Our previous house looked out onto the Botanic Gardens and its large glasshouse full of plants from Mexico and China, and it was ever so hot, so on cold winter days Mum sometimes took me down there and I enjoyed floating a little wooden boat along the narrow stream that ran between the huge trees inside. I saw no boats at sea off The Island. Just some seagulls perched on the stone wall that protected the road from the tide.

I went outside into the new garden. An old glasshouse seemed to lean against the wall separating us from the school. There was nothing in it but empty shelves and baskets and buckets and plastic pots and a spade. We had an area of lawn and a big, old pine tree that became my play area for years. It had a rounded, hollow back which made a perfect cave and a low branch I could sit and swing on, and when I climbed further up a space I turned into my special den. It was like being high up in the cab of the removal van, because I could see everything from there: out west as far as the sea stretched and down the way towards the village where other children played in the playpark next to the hall. That first summer was long and hot. I was on my own, happy breathing the warm smells of the garden from the tree.

When I played in that tree it became more than the glowing globe in my Dad’s study. The lower branches were the Nile and the Amazon and the Yangzte and the upper ones Mars and Pluto and Jupiter, from where I could look down and see the small world far below twinkling in the dark.

I sometimes think that it was lying in the tree smelling pine needles that made me interested in chemistry. Though I had earlier moments. The Christmas logs in the open fire, and the buddleia in my granny’s garden, the jasmine and lilac bushes that grew against the schoolhouse wall in the late evening sun. Their fragrance filled the air, and I fell asleep every night cradled by it.

We were fortunate. The school and schoolhouse were on the west side of the island, where the Gulf Stream keeps things warm. Even in winter, the wind and rain and frost and snow are soft and temporary, while over in the east, only three miles away, the wind was stronger, the rain heavier, the frost colder and the snow deeper. I missed some of that, of course, but always headed east with my sledge when the snow came to hurl down the big hill for hours on end.

I came to know that tree so well. Every knot and twist and turn and where I could lean, and which branches were brittle and best avoided, and where it was best to sit in the summer (right at the bottom) when all the leaves were in bloom, or in winter (right at the top) when everything was bare so I could see across the village and beyond the immediate sea towards the distant islands which sometimes shimmered in the haze and frost.

Mum continued to make our new home our own, while Dad spent a lot of time next door in the empty school preparing it, and himself, for the new school year, which started late in August with the bell clanging just over the wall. He rang it the first morning, and then gave every pupil a turn at ringing it day after day all through the year. It was an old, open bell and the harder you shook it the louder it sounded.

2

IT WAS A composite class. Primaries Six and Seven together, taught by my father. There were two other teachers – Miss MacLean, who taught the infant classes, as we called them, One, Two, and Three, and Mrs MacInnes who taught the middle classes, Four and Five.

Of course, everyone knew I was the headmaster’s son and treated me with caution. I would probably tell on them. Tell-tale tit. When I got back home and had tea, what else would The Headie’s son speak about except what Johnny had done behind the bike shed and the language Maggie used in the playground? As if either of us had any interest in finding out. I ate fast and left the table as soon as was decent, and Mum and Dad were too worried about other things to concern themselves with what the village children said or did.

I hated Dad being my teacher. My previous school had individual classes. He taught Primary Seven while I had Miss Sinclair. She was tall and thin and had a slight lisp and always finished our work for us so that we all got good marks. The annoying thing about Dad as a teacher was that he behaved publicly in front of the class as he did at home. Those embarrassing little habits which I’d have preferred to stay private. The way he stuck his pinkie into his ear when he was searching for the right word and the way he scratched himself when one of the children annoyed him.

My best friend that year in primary school was another incomer to the island, Sally Henderson. Her father had died in an accident and her mother had returned back home after years away. I suppose we both felt that we were outsiders, intruders. It’s not that anyone was unfriendly or anything, just they’d all grown up together and knew each other, and each other’s families, in a way that Sally and I never could. John was Bob’s brother, and their cousins were Linda and Cathie and Mary. They all shared bikes and stories and comics. We were always included in their games but it felt like we were guests, for they were always explaining stuff to us as if we didn’t know how to play hopscotch or the rules of walking backwards on the high wall. We tried to introduce games too. They never liked our ideas.

It’s not that Sally and I played or talked together much at first. More like when we played collectively we were always put in the same team by whoever was leader and were only ever asked to lead if it was to their advantage. When we all played rounders, for example, they would always give the bat first to Sally because they had the best bowler in their team and wanted to get off to a good start. So Sally and I became a sort of team and the highlight of our Primary Seven year was when we won the three-legged race, hopping over the playground line well ahead of everyone else. We got a balloon each for a prize. Thankfully, it was presented to us by the school cook, Mrs Campbell, and not by Dad. It helped that Sally was a wonderful athlete, later representing the high school at the Junior European Schools Cross-Country Championships. She always smelt nice.

‘Mint,’ she said. ‘It grows everywhere in our garden, so it does.’

She often said ‘so it does’ after saying something.

‘To make sure it’s true,’ she told me.

I turned out to be a very good football player. I’d always played football, at first on the street outside our house in Glasgow with my wee pals Hughie, Sparky and Sid. We called him Sid after the balloon-juggling dog in the comics, though his real name was James. He was a good goalkeeper and could catch any ball no matter how high or low or hard it was kicked or thrown at him.