Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

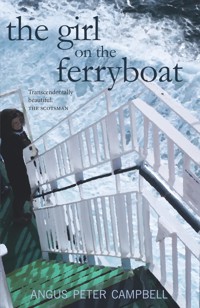

I loved her from the moment I saw her, and that love has never wavered. It has encased every choice I have ever made, and I have never done anything in my life which didn't involve her image somewhere… I'm so sorry for it all This is the latest English-language novel from award-winning Gaelic poet, novelist, journalist, broadcaster and actor, Angus Peter Campbell, and the first to be published simultaneously in Gaelic and English. Vividly evoked Scottish tale of chance encounters and of family memories, regret, love and loss. Combines myth, music and linguistics to recount the memory of a hazy summer's day on the Isle of Mull.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 298

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2013

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Angus Peter Campbell lives in Skye, and has previously published a number of works in Gaelic. In 2001, he was awarded the Bardic Crown for Gaelic Poetry, as well as the Creative Scotland Award. His Gaelic novel An Oidhche Mus do Sheol Sinn (The Night Before We Sailed) was included in The List 100 Best Scottish Books of All Time. As well as being an author, Campbell has also worked in newspapers, radio and film, with a leading role in the Gaelic language feature film, Seachd: The Inaccessible Pinnacle.

The Greatest Gift, Fountain Publishing,1992

Cairteal gu Meadhan-Latha, Acair Publishing, 1992

One Road, Fountain Publishing, 1994

Gealach an Abachaidh, Acair Publishing, 1998

Motair-baidhsagal agus Sgàthan, Acair Publishing, 2000

Lagan A’ Bhàigh, Acair Publishing, 2002

An Siopsaidh agus an t-Aingeal, Acair Publishing, 2002

An Oidhche Mus Do Sheòl Sinn, Clàr Publishing, 2003

Là a’ Dèanamh Sgèil Do Là, Clàr Publishing, 2004

Invisible Islands, Otago Publishing, 2006

An Taigh-Samhraidh, Clàr Publishing, 2007

Meas air Chrannaibh/ Fruit on Branches, Acair Publishing, 2007

Tilleadh Dhachaigh, Clàr Publishing, 2009

Suas gu Deas, Islands Book Trust, 2009

Archie and the North Wind, Luath Press, 2010

Aibisidh, Polygon, 2011

An t-Eilean: Taking a Line for a Walk, Islands Book Trust, 2012

Fuaran Ceann an t-Saoghail, Clàr Publishing, 2012

The Girl on the Ferryboathas also been published in Gaelic asAn Nighean air an Aiseag(2013), also available from Luath Press as a Hardback and an eBook.

The Girl on the Ferryboat

ANGUS PETER CAMPBELL

LuathPress Limited EDINBURGHwww.luath.co.uk

Contents

Author Bio

Also by Angus Peter Campbell

Copyright

Dedication

Acknowledgements

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

Other Books from Luath Press

First published 2013

ISBN (print): 978-1-908373-77-9

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-909912-56-4

The publisher acknowledges the support of Creative Scotland towards the publication of this book.

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

© Angus Peter Campbell 2013

for Liondsaidh and the children with loveSalmCXV111mar thaing

‘Though there be no such thing as Chance in the world, our ignorance of the real cause of any event has the same influence on the understanding, and begets a like species of belief or opinion.’

David Hume,An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Kirsten Graham, Jennie Renton, Louise Hutcheson and Gavin MacDougall of Luath Press for their editorial advice and support. To the Gaelic Books Council who supported the Gaelic version of this novel, also published by Luath. My gratitude to all those, such as Norma Campbell of Kingussie and Inverness, Ryno Morrison of Lewis, Dr John MacInnes of Raasay and Edinburgh, Dolina MacLennan of Lewis and Edinburgh, and Angus MacLeod of Rudh’ Aisinis, South Uist, who gave me little snippets which appear here. I am indebted, as always, to Fr Allan MacDonald’s lovely bookWords and Expressions from South Uist and Eriskay(Dublin: The Institute for Advanced Studies, 1958). My biggest thanks, as ever, to my wife Liondsaidh and our children for all their love, and for generously giving me the time and freedom to write this book.

1

IT WAS A LONG hot summer: one of those which stays in the memory forever. I can still hear the hum of the bees, and the call of the rock pigeons far away, and then I heard them coming down from the hill.

Though it wasn’t quite like that either, for first I heard the squeaking and creaking in the distance, as if the dry earth itself was yawning before cracking. Don’t you remember – how the thin fissures would appear in the old peat bogs towards the middle of spring?

A gate opened, and we heard the clip-clop of the horse on the stones which covered The Old Man’s Ditch, just out of sight. An Irishman, O’Riagan, was the Old Man – some poor old tinker who’d once taken a dram too many and fell into the ditch, never to rise.

Then they appeared – Alasdair and Kate, sitting gaily on top of the peat bags in the cart. He wearing a small brown bunnet, with a clay pipe stuck in his mouth, while she sat knitting beside him, singing. The world could never be improved. Adam and Eve never ate that apple, after all.

They were building their first boat, though neither of them were young.

At the time, I myself was very young, though I didn’t know it then. The university behind me and the world before me, though I had no notion what to do with it. I had forever, with the daylight pouring out on every side from dawn till dusk, every day without end, without beginning.

I saw her first on the ferry as we sailed up through the Sound of Mull. Dark curly hair and freckles and a smile as bonny as the machair. Her eyes were blue: we looked at each other as she climbed and I descended the stairs between the deck and the restaurant. ‘Sorry,’ I said to her, trying to stand to one side, and she smiled and said, ‘O, don’t worry – I’ll get by.’

I wanted to touch her arm as she passed, but I stayed my hand and she left. My sense is that she disembarked at Tobermory, though it could have been at Tiree or Coll. For in those days the boat called at all these different places which have now melted into one. Did the boat tie up alongside the quay, or was that the time they used a small fender with the travellers ascending or descending on iron ropes?

Maybe that was another pier somewhere else, some other time.

Algeciras to Tangier: I think that was the best voyage I ever made, that time I caught a train down through Spain, the ferry across to Tangier, and another train from there through the red desert down to Casablanca. Everything shimmered in the haze: I recall music and an old man playing draughts at a disused station and the gold minarets of Granada shining as we passed through.

The windows were folded down as we travelled through Morocco, with men in long white kaftans bent over the fields. I ran out of money and a young Berber boy who was also travelling paid my fare before disappearing into the crowd. That was in my third year at university, a while before time existed.

I walked over to where Alasdair and Kate and the horse and cart had now come into sight. ‘There you are, Eochaidh,’ I said to the pony, stroking the mane.

‘Aye aye,’ the old man said as we walked over to the stream to water the horse.

While Eochaidh drank his world, Alasdair and Kate and I carried the peat bags to the stack. They would shape her later. Kate made the lunch and the four of us sat round the table eating ham and egg and slices of cheese and pickle.

Big Roderick they called my boss – the best boatmaker in the district when he was sober, who would occasionally go astray before returning to work with renewed vigour, as if the whole world needed to be created afresh. At this time we were at the beginning of creation: all revelation still lay ahead.

I was just a labourer. Big Roderick’s servant.

‘The tenon saw,’ he’d shout now and again, and I’d run and get hold of that particular kind. The one with the thin rip-files for cutting across the grain. That was for the early, rough part of the work before the finesse set in and his ancient oak box with the polished chisels emerged to frame and bevel and pare and dovetail.

‘How are you getting on?’ Alasdair asked.

‘O,’ said Roderick, ‘no reason to complain. You’ll be launched by midsummer.’

‘Blessings,’ said Alasdair. ‘Didn’t I tell them there was no one like you this side of the Clyde?’

‘Isn’t truth lovely?’ said Kate.

She was called Katell at the beginning. Katell Pelan from Becherel in Brittany, but who had now travelled the world with this little man she’d married nearly fifty years ago. Since they’d first met in a house in Edinburgh where she’d been a student but working in Bruntsfield as a servant girl and he cleaning the windows before starting his apprenticeship. A while then in Leith when he worked at Henry Robb’s shipyards, and Clydebank after that under the shadow of John Brown’s, before they went to Belfast and Harland & Wolff and the long years when he was at deep sea and the children came. First the bits of Breton and Gaelic then their mutual English and at last, here they were at the end of the journey, which had come so suddenly.

Big Roderick and I were caulking the carvel planks with oakum, fitted between the seams and the hull. How simple building a boat was: like a jigsaw. You only had to use common sense. Put one part next to another.

‘Logic, boy,’ Big Roderick would say, ‘you just add bit to bit and before you know it you have a boat.’

Though we both knew fine that nothing was that simple. The difficulty of course was in knowing which bits fitted where, which bits made sense.

We rested a while by the unfinished stern, looking out west towards the Atlantic. A large vessel of some kind was sailing north.

‘So,’ he said then. ‘And did you learn anything of worth at that university of yours?’

Well, what would I say? That I hadn’t? – the great lie. Or that I had? – the bigger lie. Sartre and Marx and Hegel and all the rest.

‘Yes,’ I said, ‘though I’m not very sure what use it’ll do me.’

He lifted the gouge from his apron. ‘Never tell me that a thing is of no use. You got a chance I never had. With this gouge I can shape wood. But with your education…’

He stood up, pointing to the vessel which was far out at sea.

‘The day will come,’ he said, ‘when there will be no day like this. When we’ll all be strangers and we won’t believe a thing. Keep your education for that day.’

And we continued shaping the wood for the rest of the day.

2

THE GIRL ON the ferryboat was called Helen: she’d been visiting friends in Edinburgh and when she turned round, the violin was gone forever.

Waverley Station.

She’d only put it down on the bench for a moment as she searched for her purse, and when she looked back it had disappeared. She had that moment of disbelief: she must have left it at home, on the high shelf at the bottom of the bed above the bay window overlooking the garden, or perhaps out in the garden shed itself, where she now practised on warm summer days. Except it was now November.

No one in the world noticed, for it continued as before. It was 8.20am, the very middle of the rush hour. Everyone ran. No one carried a violin under their arm. A terrible piper busked over by Platform 17, where the train from Euston was due. An old man, still drunk from the night before, lay slumped on the bench. She wanted to shake him awake, but of course he wouldn’t know.

She searched everywhere. Beneath and behind and beside the bench. Round every other bench and seat. All over the concourse and in every shop. In the bins and toilets. She told a station guard, who told her to tell the police. The officer on duty added the fiddle to the endless list. ‘Go and try all the pawn shops,’ he suggested, helpfully giving her all the addresses.

None of them had been given a fiddle, and though she went back to every pawn shop in the city every day for the next three months, the tune was always the same: Sorry, Miss.

She visited nearby cities, visiting and revisiting all the pawn shops there too, but no one had seen the instrument. She advertised in the newspapers and in shop windows, but no one responded.

It had been in the family for generations, brought back from Naples by her great-grandfather on her mother’s side sometime in the 1880s. Though it was no Stradivarius, it made a beautiful sound: deep and mellow, yet bright and tuneful.

‘An angel made it’, the old people used to say and began to compare it to the famous chanter played by the MacKinnon family, which had been made by the fairies in Dunvegan. Nobody but a MacKinnon could play that chanter, and whenever anyone else touched it, it lost all its music.

It was given to young James MacKinnon on the way back from the Battle of Sheriffmuir. Wounded just above the left knee he still managed to hirple north, washing himself in the burns and feeding on oats and water. One night as he was crossing the Moor of Rannoch he heard a whimpering noise in the heather. A woman was dying with a child in her arms.

‘Take this child home to Skye,’ the woman said to him. And she also handed him a pouch. ‘And if you ever find yourself in desperate straits just use this and all danger will flee. But don’t open it until in real need.’

As he walked through Glencoe with the child in his arms, a terrible snowstorm fell. Collapsing in the drifts, he managed to untie the pouch to find the silver chanter. Raising it to his lips, he blew and instantly the snow ceased and a beautiful starlit night emerged. The young boy child turned out to be a MacCrimmon from the famous piping dynasty: their magic was also that of the MacKinnons.

Helen’s great-grandfather was a sailor in the days when ships were made of oak and canvas. Rumour had it that he’d sold a crew member in exchange for the violin, but that was mere envy on the part of those who watched him become a famous musician on his return from voyaging overseas. He became a favourite of Queen Victoria’s, and an iconic photograph of Her Majesty with Scott Skinner on one side and Archibald Campbell on the other can still be found in the vaults of the National Portrait Gallery in Edinburgh.

She herself was twelve when she was given the fiddle by her mother. After Archibald died it was played for a while by his youngest son, Fearchar, but when he died with the millions of others in the trenches, the fiddle fell silent for two generations. Helen’s mother found it one day in the loft of the byre beneath a pile of old straw and had it restored, first of all by George Smith the local carpenter, and then by the London firm of violin repair specialists, Deroille and Sons of Charing Cross.

Their leading repairer, Vincent Deroille, was so impressed by the violin that he tried to buy it, but Helen’s mother refused, telling him that it was a family heirloom which would never leave the family as long as she was alive. Which of course was something of a reimagined history, given that it had lain uncared for in the byre for nearly a century.

‘Not to worry,’ her mother said when she phoned to tell her the news.

‘It’s an impossible thing to lose. It may have gone out of our sight, but his eye will still be upon it.’

This omnipotent eye was her grandfather’s, which still kept a close watch on the fiddle from beyond the grave.

‘It will burn in the thief’s hands,’ she said. ‘The instrument will refuse to play.’

This faith was not an unreasonable thing. Had not everything that had ever been stolen ultimately not turned into ashes? Was it just some kind of strange coincidence that her own sister’s husband had died no sooner than he remarried? And what about that time the minister’s motorcycle was stolen from outside the manse, only for them to find the bike and rider at the bottom of the ravine the following Sunday?

She was on her way home now to deal with it all. Not the loss of the instrument, of course, but the grief and the story which lay behind all of that. She decided to take the bicycle. Her hands felt safer that way, gripping something solid, pushing it gently along the platform at Queen Street. How beautifully the spokes turned as she wheeled it along. The red Raleigh badge flashed with each revolution.

She put the bike in the guard’s van and sat by the window in carriage B, seat number 24. Not that any of that mattered: she just noticed it. Westerton and Dalmuir and Dumbarton Central, then the long familiar curve and climb through Helensburgh Upper, Garelochhead and Arrochar and Tarbert.

She read Pynchon and stared out the window. The hazels bent towards the windows. They were the best trees too for preventing landslides. Their long roots held in the thinnest of soils, binding the loosest things together.

Mull was where they’d finally settled, though settled might be too staid a word for it. A croft no less, or at least a smallholding, where her mother had gone ‘back to the earth’ and brought the four of them up self-sufficiently in a heaven of pigs and hens and goats and sheep and cattle and horses, in a paradise of oats and grain and carrots and leeks and potatoes and herbs.

How gorgeous it was to wake up in the morning to that smell of bread. How you took the cream off the milk and kept it in wooden basins in the shade until the whey separated from the curds and the marvel – the ingenuity! – of that home made churn which slowly transformed it all into butter. The dirtier the potatoes from out the ground the better. She smiled. How sweet the first tiny tomatoes always tasted, and as she closed her eyes she could see the apples and pears falling, one by one, into her sister’s wicker basket. Mull, the lovely Officers’ Mess.

Her ambition as a child was to be a watchmaker. She was fascinated by them: how the numbers always remained fixed while everything else moved. The hour hand invisibly, the minute hand ever so slowly, the second hand always fast and steady. She would close her eyes and count to sixty, but she could never get it exactly right. As she spoke sixty, the seconds hand would always either be moving towards fifty-nine or just one second past the top.

Her mother had a beautiful gold watch with Roman dials which Helen loved. She’d remove it and leave it behind on the dresser any time she went out to work in the fields and Helen would then always try it on. It was too big, but if she wound the leather strap twice round it fitted halfway up her arm perfectly. The numerals were diamond studded and luminous and Helen would crawl into the cupboard beneath the stairs where they would shine green in the darkness.

She remembered going into the old clockmaker’s shop in Tobermory where time was completely fluid. Archie had dozens of clocks on the walls, all showing different times. A handwritten sign under each one taught you that while it was 12 noon in Tobermory it was 2pm in Berlin, 7pm in Kuala Lumpur, and 6am in New York.

Numerous clocks and watches lay open on the long wooden work bench that ran all the way beneath the windows. ‘Would you like a look?’ Archie asked her and she nodded, and he handed her the magnifying glass he used himself and she disappeared into a gigantic world of wheels and spokes and hooks and wires.

‘See,’ Archie said, ‘if you do this – see what happens,’ and he touched the edge of a wheel with a needle and it moved, catching the wheel next to it until it locked and the two wheels spun, dancing. ‘Try it.’ And she touched this and that moved, and touched that and the other thing and another thing and another thing moved.

‘We’ll make a watch,’ her mother said to her on the way back home and they went down to the shore to gather shells. Tiny little corals of all shapes and sizes which the two of them then strung together once they got back home and tied together with a thin thread of lace. ‘There,’ her mother said to her. ‘Now it can be any time for you.’ And of course like all of us she made daisy watches and blew the seeds off a dandelion to find the right time: blow hard and it was early, soft and it would be late.

I must have travelled on the earlier train, otherwise I would have seen her then. She was very beautiful, with natural auburn hair and freckles, though that’s only a haphazard brushstroke. She was studying Ecology, doing her thesis on the nature of the native woodlands of the south-west of Mull.

This was a familiar journey. Once off the train, the left turn down by the shellfish stall across the wooden pier, then the sail out past Kerrera with the Lynn of Lorne and Lismore to the starboard side, Kingairloch and Morvern ahead. Kingairloch from Ceann Geàrr Loch, the head of the half-loch.

As she sat sunglassed on deck I must have been below in the steerage, drinking. It was all whisky in those days, with accordion music and yelping dogs and returning sailors singing about South Georgia, though some of the drovers on their way to the South Uist cattle sales sang their own songs:

‘O, gin I were far Gaudie rins, far Gaudie rins, far Gaudie rins, O gin I were far Gaudie rins at the back o Bennachie,’ and up the Sound of Mull with a drunkard standing on one of the tables crying, ‘Fareweel tae Tarwathie, adieu Mormond Hill, And the dear land o Crimmond I bid thee fareweel, I am bound now for Greenland and ready to sail, In the hopes I’ll find riches a-hunting the whale…’

I needed air. Fresh air. Up on deck the heather on Mam Chullaich was still singed from the muirburning and the sky a clear blue to the north-west, where everything lay. I was hungry and made for the restaurant downstairs.

She was at the bottom of the steps as I descended. Dark curly hair and freckles and a smile that split the skies. We looked at each other as she climbed and I descended.

‘Sorry,’ I said to her, trying to stand to one side, and she smiled and said, ‘O, don’t worry – I’ll get by.’

I wanted to touch her arm as she passed, but I stayed my hand and she left.

I think I just had soup, though I can’t really remember. I may have gone to the bar afterwards, or reclimbed the stairs up to the deck area to look for her, but she wasn’t there. The boat berthed first at Tobermory where hundreds of passengers, mostly tourists, disembarked. Others disembarked at Coll and Tiree and Castlebay and of course she must have come off with the crowd at one of these ports for I never saw her again.

I remember a girl carrying a bicycle over her shoulder at one of the ports, descending the ramp cautiously then jumping swiftly on to the bike at the bottom of the gangway and heading off across the pier, dodging round the porters.

Once she left the pier she ascended the hill past the hotel and out the old mill road past the brewery which took her to the single-track road to Dervaig and on to Calgary. It was a May morning and the ditches overflowed with buttercups and primroses. The sounds of birds filled the air: she knew them all by note. Thrushes and willow warblers and linnets and goldencrests. The finches high overhead. The plovers swooping up and down beside her through the glen. The smell of wild garlic filled her nostrils. O God, the glorious days before traffic.

Her mother was milking Daisy down by the gate. She still looked like a young girl herself, her long hair, though now flecked with grey, blowing in the breeze. Helen stopped at the top of the brae listening to the scene: the endless songs of the birds, the wind in the silver birches, the sound of the milk squirting into the pail. Her mother sensed her there and turned, still sitting on her stool, and waved. She cycled down towards her and stroked Daisy as the milk continued to flow.

Inside, they embraced.

‘It’s so lovely to see you, a ghràidh,’ her mother said, smiling. ‘You look wonderful.’

‘You too,’ said Helen. ‘All that fresh air.’

They made tea and had some scones.

‘How’s Glasgow?’

‘Oh – so so. As you would expect. All noise and fun. And pollution.’

‘Studying hard? Not that it really matters.’

‘Yes. No. Not because it matters but… because it matters.’

They both smiled.

‘So,’ her mother said, ‘you lost the fiddle.’

‘Yes. Sorry.’

‘As I said on the phone, it doesn’t matter. It’ll turn up. Someplace. Sometime.’

‘I’m sorry,’ said Helen again. ‘It was just a moment. Seconds really and that was it.’

‘It always is.’

‘Shall we go outside?’ Helen asked. ‘Into the orchard?’

She was talking about the death of her father. Helen was then only five. There was no reason for it really – just an ordinary day, no wind to speak of, but the line somehow got snagged on the winch and she went down in seconds according to the coastguards.

‘When we lose something,’ her mother was saying, ‘it always goes somewhere. Nothing ever just dissolves. You know the Gaelic saying?’ “Thig trì nithean gun iarraidh…?” ‘Three things come unsought – fear, jealousy and love.’

‘And which of these…?’ asked Helen.

Her mother smiled.

‘All three, of course. Though not necessarily in that order.’ She stood up and plucked an apple from the tree. ‘I loved him immensely. And I feared for him immensely. And I jealously guarded him from himself. Though I failed. For we always fail.’

She put the apple down with the others in the wooden press, and turned the handle to squeeze out the juice which trickled into the jar below.

They walked arm in arm out through the willow arch and began climbing the brae at the back of the house. The collie dog, Glen, joined them, always hopeful. They rested at the top of the hill looking westwards towards Coll where the boat on which I stood was sailing, at that moment passing Rudha Sgùrr Innis and the Eilean Mòr, making for the open sea.

3

WHEN HE WAS nine, Alasdair’s grandfather took him out sea-fishing for the first time.

It was the first Saturday of the summer holidays, and all the more glorious because he had no notion it was going to happen. The sound of the heavy rain on the zinc roof woke him and when he looked outside through the tiny attic window the sky was dank and heavy.

He climbed back into his closet and lay on his back listening to the drumbeats of the rain. It rattled against the zinc, then if he listened really carefully he could hear it separating at the ridges and running in streams down the vents to the eaves. He raced them against each other. There were five vents to each corrugated sheet. He focused on the one above his head. The outside vent was Paavo Nurmi. In vent two was Jesse Owens. Joie Ray in vent three. Jackson Scholz in four and the Albannach, Eric Liddell, in the inside lane.

Off they went, Roy running so fast downhill but quickly overtaken by Scholz in lane four, and then came Owens and Liddell, each keeping pace with the other, step by step, but in the last sudden rush down to the eaves the great Paavo Nurmi won, once again, and the race started all over again.

When he woke the second time all was quiet and still. He heard his grandfather’s voice downstairs so he immediately jumped out of bed, dressed in seconds, and was with him before his voice died away.

‘Alasdair!’ his grandfather said. ‘We thought the fairies had taken you away during the night! What kept you so long?’

‘The race,’ he said. ‘It was fantastic. Nurmi won again!’

His grandfather smiled.

‘One day, Alasdair, you’ll run as fast as him too. Now – where’s your stuff?’

‘Stuff?’

‘Aye. Your stuff.’

‘Oh,’ said Alasdair, running out into the byre.

He climbed the wooden ladder up into the drying straw where the rod was hidden. His grandfather had made it for him last winter, just as the snow had settled in. They’d gone out rabbit hunting in the afternoon and instead of taking the usual shore road home had cut east through the only surviving wood in the area. ‘Birch or hazel would be best,’ his grandfather said, ‘but we’ll just make do with whatever has fallen.’

They searched for ages, but each fallen branch that Alasdair brought back was somehow deficient – too small, or too thick, or too soft, or too brittle – but finally he found a long thin willow twig which his grandfather said was ‘perfect’.

‘You carry it home,’ his grandfather said, and no prouder soldier ever marched with his rifle held firmer over his shoulder. He was Alasdair MacColla and Gille-Pàdraig Dubh and Robin Hood and Daniel Boone all rolled into one.

Back home, his grandfather took out his whittling knife and helped him shear off the sprigs and nodules.

‘Now let’s soak it in the old feeding tub overnight.’

The old feeding tub was filled with sheep’s urine ready for softening the tweed.

‘It’ll make the wood nice and pliable.’

And it did. By morning, Alasdair could bend and manipulate the willow rod any way he wanted.

‘You want it that way to bear all the salmon you’ll catch!’ his grandfather said to him.

And then as the snow fell for days on end the two of them sat by the fire slitting the rod, fitting the thread, turning the weaving thrums into fishing spindles, and seasoning and polishing the rod.

He now grabbed it out of the straw and jumped down from the byre ladder with it.

‘It’s only for show,’ his grandfather said. ‘We’re not going to the river today. But don’t tell your mother. We’ll keep it as a surprise for her later. Let’s eat first.’

He walked with his grandfather down by the peat stack and across the moor road which took them by the river and the twin lochs. But once out of sight of the house his grandfather turned east and led him down through the small ravine which separated the moorland from the grazing slopes. They clambered over the rocks until they reached the heights of the bay overlooking the sea. It glittered silver far below them. To the far south they could see the small hills of Barra blue on the horizon. Out west all was ocean as far as America. Beyond the bay itself, the mountains of Skye ascended into the air.

‘Are we?’ Alasdair thought, but didn’t speak the words out loud. His grandfather – how nimbly he moved! – led the way downhill. Almost running, really. They reached the bay where his boat lay. Reul-na-Mara it was called – The Star of the Sea. The number of times Alasdair had dreamt of this moment: of standing here with his grampa beside the boat, ready to sail forth.

‘Up you go,’ he said, lifting Alasdair into the boat in one movement. ‘You hold that rope,’ he said, and the world began.

His grandfather took to the oars while Alasdair sat in the stern at the imagined tiller. His grandfather rowed steadily, taking the wee boat out of the harbour, round the skerry on which the seals basked. Alasdair could see the sandy bottom through the strands of seaweed. Millions of tiny fish, no bigger than his own pinky, moved beneath the water.

‘They’re called sìolagain,’ his grandfather said. ‘Sand eels. Can you count them?’

Alasdair tried.

‘A million,’ he said. ‘And one.’

Once they’d cleared the skerries his grandfather offered him the oars.

‘Sit right there,’ he said. ‘Square-on in the middle. And hold this one like that – that’s it – right between the thumb and the palm, and I’ll row with the other one until you get used to it.’

Alasdair splashed and thrashed the water pointlessly, but eventually got the hang of slicing the oar in at the backward angle until it furrowed in through the water then rose again.

‘Try this one as well,’ his grandfather said, handing him the other oar. It took even longer to coordinate the oars as they went round in tiny circles. But his grampa seemed quite relaxed about it all, lighting his pipe and sitting in the stern. Eventually Alasdair managed to move the boat forwards with balanced little strokes which stirred the water around them.

‘Keep your eye on that point over there,’ his grandfather said, ‘and row towards it. You can’t go wrong.’

Alasdair kept his eye fixed on the landmark he had given him, the roof of the old church at Eolaigearraidh which stood on the highest hill in the distance. His arms and hands ached but he would never let his grandfather know. Paavo Nurmi never tired.

Suddenly they appeared on the near horizon, leaping high out of the ocean.

‘Whales!’ he cried. ‘Grampa – look! Whales!’

A whole school of them lay ahead making rainbows in the sky.

‘Mucan-biorach, a’ bhalaich,’ his grandfather said, smiling. ‘Dolphins, lad. Though we have dozens of different names for them in our tongue – leumadairean, deilfean, bèistean-ghorm, peallaichean… depending on which kind they are.’

He cupped his old hands round his eyes.

‘These look likemucan-biorachto me. Aren’t they beautiful?An giomach, an rionnach ‘s an ròn – trì seòid a’ chuain!The lobster, the mackerel and the seal – the three heroes of the ocean! Whoever spoke such nonsense! You’ll never see a more beautiful sight on all the earth than these dolphins leaping before you.’

Alasdair wanted to hear his stories again, and grandfather knew it.

‘Innis dhomh mun deidhinn – tell me about them. Please.’ said Alasdair, and his grandfather once again began telling of how he’d sailed round Cape Horn in the sailing ship.

‘I was fifteen days up there, in the crow’s nest, icicles hanging from my beard.’

Alasdair knew that the icicles grew longer each time he told the story.

‘How long were they?’

‘Oh,’ said his grampa, ‘this long.’ And he stretched his arms out as wide as he could. ‘They were hanging from my chin down to below my knees,’ he said. ‘The ship’s master had to saw them off with heated shears.’

Nearer, Alasdair could clearly see that the dolphins were not black at all, as they first appeared, but grey and blue. It was impossible to count how many there were, for each time two or three dived, another two or three surfaced. At any given time seven or eight of them leapt high into the air in semicircles.