Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Luath Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

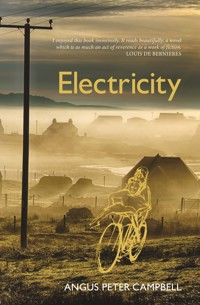

'In pencil-written and drawing-spattered notebooks intended for her Australian granddaughter, an elderly woman, now in Edinburgh, remembers and relives her Hebridean childhood. The community thus recreated is one where modernity – its emblem the Electricity of Angus Peter Campbell's title – collides and overlaps with all sorts of linguistic, cultural and other continuities. But this is no sentimental or elegiac excursion into a long-gone past. What's evoked here is a powerful sense of what it was, and is, to grow up amid family, neighbours and surroundings of a sort providing, for the most part, both security and happiness.' JAMES HUNTER

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 634

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

ANGUS PETER CAMPBELL is from South Uist. He has worked as a lemonade factory bottle-washer, kitchen-porter, labourer, forester, lobster-fisherman, journalist, broadcaster, actor and writer. He graduated from the University of Edinburgh with Double Honours in Politics and History. His Gaelic novel An Oidhche Mus Do Sheòl Sinn was voted by the public into the Top 10 of the Best Ever Books from Scotland in The List/Orange Awards of 2007. His poetry collection Aibisidh won the Scottish Poetry Book of the Year Award in 2011 and his novel Memory and Straw the Saltire Scottish Fiction Book of the Year in 2017. Tuathanas nan Creutairean (George Orwell’s Animal Farm in Campbell’s Gaelic translation) appeared in 2021. Constabal Murdo 2: Murdo ann am Marseille won the Gaelic Literature Awards Fiction Book of the Year Prize for 2022. In 2023 he was named as the Gaelic Writer of the Year at the Highlands and Islands Press Ball Media Awards.

LIONDSAIDH CHAIMBEUL, who made the drawings in this story, is an Honours graduate of Edinburgh College of Art. She works as a sculptor, designer and school bus driver. Her art work is on display in public places from Benbecula to Irvine and in several private collections. She represented Scotland at the first ever Scottish International Sculpture Symposium in 1986.

First published 2023

ISBN: 978-1-80425-089-1

The author’s right to be identified as author of this book under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon by

Main Point Books, Edinburgh

Images © Liondsaidh Chaimbeul

Text © Angus Peter Campbell 2023

One can always exaggerate in the direction of truth

Matisse

Contents

Acknowledgements

My Dear Emily…

1 Silver Morning

2 Home

3 Mam

4 Dad

5 Niall Cuagach

6 James Campbell

7 Lisa

8 Electricity

9 Mrs MacPherson

10 The Cèilidh

11 Fair Saturday

12 Frog Sunday

13 Old Murdo and Mùgan and John the Shoemaker and Hazel and Effie the Postmistress

14 The Meeting

15 After

16 The Den

17 The Cows

18 Cycling

19 Flying

20 Ploughing

21 Hydro

22 Polishing

23 Together

24 Switched On

25 Antoine

26 Edinburgh

27 Returning

I write this by candle-light, Emily

Acknowledgements

MY THANKS TO everyone who helped make this book. To Louis de Bernieres, Catherine Deveney, Professor James Hunter, Fr Colin MacInnes, Karen Matheson and Selina Scott for their generous endorsements. To Peter Ferguson for the cover photograph. To my wife Liondsaidh Chaimbeul for the beautiful map and hand-drawings as Annie, and to my daughter Ciorstaidh for the drawing of the yellow on the broom. To Jennie Renton, Maddie Mankey, Amy Turnbull and Gavin MacDougall at Luath Press for their work and support. My special thanks to Gwyneth Findlay who edited the novel with grace and precision. She said on first reading the novel that it was like getting a big hug. I hope that you also feel the same, warmly welcomed into this community by Annie, Mùgan, Niall Cuagach, Lisa, Sgliugan, Hazel, Dolina, Mrs MacPherson and all their pals. Taing dhaibh, agus tapadh leibh uile. Enjoy!

My Dear Emily,

I hope you’re well. And may Gran’s adventures make you feel even better! Remember that time we camped out for the night? I know it was just the back garden, but you said it was like being in the middle of the forest, because you could hear the wind blowing through the trees and the owls hooting far off. We were at the centre of everything. And how we both snuggled into the sleeping bags and lit our wee torches and then played shadows on the canvas, and you said it was an elephant when it was a mouse and then when we put the torches together yours was the sun and mine the moon! In the morning, I was the only one who heard the birds singing, for you were fast asleep in my arms. Said you were cold during the night though we both knew it was just an excuse and I was so pleased when you snuggled in and slept, breathing warm as toast, while the wind whispered outside. All that mattered was that we were alive and together.

I wish I could go over and see you, or that you could fly over here. If I were with you I’d hug you long and close, and I know I’d want you to hold on and never let me go. I’ve written down my story for you, as promised. As a sort of tent in which we can coorie in! Everything has kind of raced by, and all I want to do is to tell everyone I ever met how beautiful and strange they all were.

Once upon a time, it seemed as if change came from the outside, like a gale-force wind, when all the time it was ourselves. But you can shelter from the wind. I look in the mirror and see the changes. Those lines on my forehead when I deliberately frown, and the way my mouth purses when I put on my lipstick. Inside, I am forever the girl I was, running across the machair in the middle of May inhaling the sweet smell of the clover while the larks sing overhead.

I had wee headaches at first and didn’t think anything of them. Though Mam said she’d also had them when she was my age and that they would go after a while. Which they did. There were some things we didn’t talk about in those days. You just found out about it by magic, as it were. Like finding an unknown object on the shore and by handling it discover it was light and made of plastic, and that if the bit at the end was fixed (which Dad repaired) it could fly! It was a toy plane. Things can surprise us.

The thing that happened was that I grew up the same time electricity arrived. It was as if the two were directly connected. The way the bulbs sizzled when they were first lit was the way I felt. Crackling and fusing together and then illuminating everything with that soft, flickering light.

But we also feared it. Sensed that nothing would ever be the same again. Dad feared the loss of the hearth and the fire. Mam knew what speed meant. It spoilt the making of things. She always did things slowly. Carved the bread as if it felt every cut. Milked the cow gently, because it made the milk creamier. Folded the tablecloth ever so softly, because the linen remembered all her kindness. In the midst of it all I met Antoine, and it was as if the whole place was lit up by will-o’-the-wisp, with my bike and the grass and the seashells all shining! It’s all that matters, those moments. Remember how the moths all hovered outside the tent that night, vainly trying to get in? They never did, and once we turned the torches off, all was silent, except for your quiet breathing, and me trying not to breathe in case I woke you.

Everything will pass, my darling. That’s all. The bad too, so hold on to the good, for its day will come again. And just to remind you of the shadow-shapes we made with our hands in the torchlight, I’ve done a few drawings to chum all these words I’ve written. They are in memory of dear Mrs MacPherson, who made the best cup of tea and the nicest scones in the whole world, even though you think Gran does!

I learned the recipes from her, so really it’s always been her scones. As is everything else, sort of hand-me-downs which arrived like lightning and quiver on like a candle. You know fine I can work a computer, but I’ve written all this out by hand because you once told me that you liked my hand-writing since it was like those white swans we saw swimming in Inverleith pond! Remember, a dog barked suddenly, and the swans looked at each other, as if wondering whether to fly away, but then just dipped their heads into the water and carried on fishing.

Isn’t it amazing how we remember all the details of some things, and can’t remember a thing about others? Bet you remember the name of your first pet and infant teacher! Flora the Frog and Miss MacIsaac! It’s a beautiful starlit night here in Edinburgh.

I was down the bottom of the garden earlier, just as the sun set. The maple and cherry trees were red and orange, and Hector the Hedgehog, my daily evening visitor, was trundling along as usual between the gate and the hedge. He loves the apple cuts I leave for him there every night. When you next come over, bring some of those Fujis with you, which he likes so much! They’re impossible to get over here. Poor old Hector has got such a sweet tooth!

I know it’s daft, but you know what I’ve done, Emily? The reason I was down the bottom of the garden was not just to feed Hector, but to set up the tent! It’s a warm night and I’m going to sleep out there for old times’ sake. Don’t worry – I’ve got three hot water bottles ready and those fluffy pyjamas that you said make me look like Paddington Bear! Come out with me and if you take your torch we can once again make the sun and the moon and the elephant and the mouse. And if I get cold, can I just snuggle in beside you so that I get nice and warm, like toast? Let’s, Emily!

Oh, and I got a large packet of the Liquorice Allsorts we both like we can share with everyone. I promise I’ll keep the yellow ones for you and the stripey white and black and orange ones for myself, and folk like Campbell will just have to make do with the plain sticky black ones, so there!

Love, Gran xxx

1

Silver Morning

IT’S BEEN GOOD. When I was wee we used to play a game. Dolina and me. As we cycled along, she counted the things to her left, and I counted the things to my right. The houses and the people and the stones and the walls and the sheep and everything. Without cheating, because that spoilt the game. You couldn’t just say that you saw five starlings when there were only three. We made up stories about everything we saw.

The big rock as we turned northwards by the machair track was Helen Carnegie who’d been turned to stone by the wicked witch, and the river that ran into the sea was the Mississippi for me and the Amazon for Dolina. Mine had swamps we had to swim through, and hers had crocodiles we had to wrestle with to get to the other side. They always took big bites out of our legs.

We also played houses. Pebbles were little cottages and we made long and winding sandy roads up to them and kings and queens and princes and princesses and witches and goblins and magicians lived in them. Smoke always curled out of the chimneys, and I still can’t draw a house without putting a wee road up to the door and two matching windows and a curl of smoke rising up to the blue air. The door is always open and the kettle forever on the boil.

There was a small cave down by the shore that was our first castle. Duncan and Fearchar helped us pull an old cupboard door down to the castle, and if anyone wanted to enter they had to knock three times on the door with this special white stone before they were allowed in. Inside, we had sticks and a kettle and a cupboard and shelves and everything where we held big feasts. In the summer when the days were long and there was hardly any night we lit a fire and roasted marshmallows on sticks and then ran and danced until the sun shone orange.

I’m writing with a pencil because that’s how I learned to write at school, and I know that if I make a mistake I can rub it out and start again. We used to rub things out with the heel of the white loaf, but these days I use Jamieson’s round erasers. I get them from Simpson’s round the corner. Thing is, with the loaf you could still see the smudge, as if writing and sums had as much to do with rubbing out as putting in!

Same with everything. Mam was forever washing things and Dad always clearing fields so that the potatoes would grow. It was as if nothing could happen without something else being removed. When Niall Cuagach divined for water he never knew where the exact spot was, or whether it was a trickle or a well. We watched him following his stick ever so carefully and then came that remarkable moment when the twig twitched, and there it was. Water. It was as if the stick was alive in his hands. He gave us the stick to try, but though we waved it about everywhere we never found water. It only ever worked for him.

The first time Mam gave me a pencil when I was about two or three she cupped her hand round mine and made this amazing shape which she said was an ‘a’, and then she cupped my hand and made a different shape and said ‘And that’s a capital A’. It was like the difference between a lamb and a sheep, I thought. I got it right first time and didn’t even have to rub it out and that’s been my aim all my life.

The birds are singing outside. They are always at their best at this time, first thing in the morning, as if every new dawn is a surprise to them, needing a song. Goodness, the way Claudia my neighbour moans, as if it’s a trial being alive. I’m lucky, because I have trees in my garden, so all the birds gather there, summer and winter. They’ve grown since you last climbed them! I sleep well enough, though I wake early. But no matter how early, the goldfinches are always up before me. The gowdspinks. On spring and summer and autumn mornings they are in full song by six or seven, but even in winter, because I put seed out for them, there they are as soon as the sun rises. Maybe the sun himself rises when he hears their songs?

I’ve had my breakfast. Today, fruit and yoghurt. And black decaffeinated Earl Grey. The one with the blue cornflower blossoms and bergamot you thought was a perfume the first time you were here! I add orchid petals. For the antioxidants, I tell myself! Though it’s really for the colour which matches that gorgeous Japanese pot you bought me from the charity shop.

Oh, and did I tell you I bought a stove? The man installed it a while back, but it wasn’t working properly. Then he came back and fixed the flue. Blamed the flue of course, saying it was faulty! And you know what? The local garage down the road sells those bags of peat, and once the fire gets going good and proper with wood and a handful of coal I add the peat so that the fragrance of my childhood fills the air. Forgive an old woman adding her bit to global warming, my dear child!

It’s a silver morning here. The sun is shining in through the kitchen window and the percolator is already bubbling. Wasn’t it lovely being outside on a clear and starry winter’s night? We might have been eaten by moths or frogs! Or been invaded by those starships you said you saw flying between the moon and the horizon! And isn’t it nice too to be back inside, the stove cosy and warm, and the smell of coffee in the air, and this new day and the chance to tell you all those other things I forgot to tell you about after the man in the moon fell asleep when the clouds covered him! Remember?

2

Home

WHEN I WAS your age I often felt as if everyone else was smarter and better and prettier, and could run and do sums and all kinds of things better than me. Now it doesn’t matter so much. Who cares if Mrs MacPhee next door can still play 18 holes of golf every day when it’s enough for me to walk down to the local shop? It’s not a competition.

At first, the world was Mam and Dad and Duncan and Fearchar and me. The boys shared a bedroom, and I had one for myself.

Your great-uncle Duncan is three years older than Fearchar who is two years older than me. I don’t suppose it matters much now, though it did then. Duncan the big boy, then Fearchar in the middle, then me. Like steps on a stair. Though it was more like a triangle. Duncan at the top tip and Fearchar and I at the angles at the bottom. Otherwise it wouldn’t be a triangle, as our maths teacher always said. With Mam and Dad I suppose it was a pentagon! And once we add the rest of the family we have an apeirogon where we all hold one another together! Or maybe it’s all a circle?

Everything in the world is a different shape, Niall Cuagach used to say. A round wheel can be bent, but a circle is a circle forever. Old Gillies the blacksmith used to put the wheels in the forge and make different shapes of them. He would thin out and thin out a bit of iron until it was like chewing gum. It was amazing how far he could stretch it and how long he could make it.

Strange to think that time itself is like that, and that now I’m seventy, I’m still ten as well. Like a piece of stretched iron where the longer you pull the thinner it gets, though still tied together like an elastic string. The same as playing shadows. Your shadow is sometimes ahead of you and sometimes behind you or to the side, depending on where the sun is shining from. And strange how it’s always longer or shorter than you are. You jump to try and catch it, and you never do! I remember being a baby and lying in my cot watching sunbeams dancing in the air. I tried to catch them but they always floated away. Upwards and out the skylight window. I mind the time you were here and because the sun was obscured by the tree where I stood your shadow was longer than mine. And then you asked me to stand where you were and you stood where I had been and you were so pleased that Gran was back to her normal bigger size!

I’ve been thinking about how we all dress up. Ministers in their collars and football players in their strips and pop singers in their outrageous costumes! Duncan took to wearing a cap when he was in Primary Seven. He could already lift the old stone by the gate shoulder-high and soon managed to raise it above his head and became a proper man. Because that was the sign, all the boys said. He imagined he had grown-up things to do. Planting the potatoes in spring. Keeping an eye out for the shaws appearing. Harvesting them at autumn. Cutting the peats, gathering tangle from the shore, driving the tractor when Dad was busy with other stuff. I think he lost his childhood being big. For a while he took to walking backwards whenever he could, claiming that strengthened his leg muscles so he’d be able to run faster than anyone else and win all the races at the annual games.

When he drove the tractor he pretended he was Captain Cook and Daniel Boone, his eyes forever on the horizon, conquering the world. There was no end to it, he said, for beyond our fields were more fields and the moor and the mountains and then the mainland. On the other side the machair and the sea all the way west to America. The blue and gold history school book said it was the land of the free, so you could do whatever you wanted there and it wouldn’t cost a thing, unlike here where even a penny caramel cost tuppence out in MacLean’s shop, because by time it got here, old MacLean said, he had to pay the man who made it as well as the train-driver who carried it to Oban and then the ferry workers who took it all the way across the Minch as well as the porter who carried it up in his barrow from the pier.

Our house was the last one in the village, next to the machair. We had a green door. A kitchen to the left and a sitting room to the right and Mam and Dad’s bedroom at the back. Duncan and Fearchar and I had the two rooms upstairs. From the windows we could see the sea at the back and the whole village from the front stretching out towards the wide moor. There was endless talk of putting an airstrip out there by the old cattle-fold which we looked forward to so much because we could then fly off quickly to the mainland. But we knew it would never happen, because grownups were always talking about things they wouldn’t do. Unless the fairies themselves built it and why would they because they liked the peace and quiet and the long flat green space where they could run and play all night long.

I was the first to discover the Arctic. I found it the day after Christmas in a dark crevice under the wee stone bridge – a heavy block of ice which neither Duncan nor Fearchar had noticed. I was smart enough not to take it home because I knew it would melt. And I never told them. Even though it lasted through till the beginning of summer. By then it had diminished into a thin sliver of ice. Then it disappeared. It never came back. I know because I looked for it for years. Next time you come over to visit during your summer we’ll go down to the Lothian Burn which always gets frozen over in January. I bet you won’t believe how well your granny can still skate. But only as long as you hold my hand!

We had hardly any books when I was growing up. Most people had none. Written words aren’t everything, after all. Old Murdo brought back from sea hundreds of yellow magazines called the National Geographic and whenever Duncan and Fearchar and I called in to give him a loaf Mam had made, we’d watch him reading the magazine. He was forever talking about The Plantations, saying that was why everyone smoked so much.

We weren’t allowed candles in our bedrooms in case we knocked them over and set fire to things. We would peer out and follow the trail of candlelight on the other side of the road as Mrs MacPherson moved from the kitchen where she spent her evenings and slowly climbed the ten steps to her bedroom where she threw fascinating shadows behind the curtains for a while until it went completely dark. She never jumped steps like we did.

When the electric came, folk always said it must have been so dark before. Well, it never seemed that way to us, we had as much light as the seasons gave us. Light all day and all night in the summer time. Besides, in the dark you hear everything, like when you’re cuddled up in bed and can hear your own heart beating. I remember you telling me that’s part of the reason you go camping. To hear your own heart thumping while the owl hoots and the stars crackle. Some say it only reminds them of how alone they are, but when I hear my heart beating as I lie awake at night it makes me smile with the joy of still being alive.

I talked to the birds. They were my friends. They listened, and had so much to sing about too. Their songs were all learned ages ago. The little robins perching on the window-sills in the winter, waiting for crumbs. The owls crooning to one another in the eaves of the old barn. The peewits – peesweeps we called them – always inviting us to play high up in the skies. The swallows whooping in every spring, telling Dolina and me about Africa, where they couldn’t even land on the burning desert.

Mrs MacPherson told us that the swallow was the spirit of a young woman who got lost out on the moor years ago and now spent her time travelling the world crying for her Mam. Everything meant something. The best games I had were with the oystercatchers and curlews. I ran after them, along the shore, and allowed me to get near, then ran away again. I liked watching the cormorants and wild ducks and swans running across the water, flapping their wings and taking off into the blue sky.

Like Dolina and Peggy and Katie and myself when we played. The ancient standing stone was home. Katie had a scarf we used, tight over the eyes and tied with two knots at the back.

‘Else you’ll all cheat,’ Katie always said.

Then we counted, the numbers getting louder. It’s always the best part, isn’t it? One to TEN! Sometimes to ONE HUNDRED, when you could go off and hide at the end of the world. Here I come! And everyone was invisible. Nothing moved.

Sometimes the boys asked the girls to play ‘soldiers’ with them – knocking the heads off stalks of ribwort. If any boy found a toad or a frog, or even a mouse, they cut it into pieces with their pocketknives. Except for wee Davie MacNeil, who they pushed away and called a jessie. I liked him, for he always shared his pieces with us and offered to carry our bags without it meaning that we’d have to give him a shot of our bikes or anything. Cycling through mud and holes and puddles was never good enough for the boys, they also always had to do wheelies. Show offs!

They were always scratching their names on the school desks and dinner tables and even on the rocks outside, leaving their marks wherever they were. And every playtime we could see them standing in a row seeing who could pee highest, as if the mark they reached on the wall meant something! To us, the boys smelt. Or maybe it was just that we girls smelt differently. Whenever anyone lost a jersey all you had to do was sniff it and you knew instantly whose it was.

Dolina and I wished we were in an all-girls school like they had in the comics and on the mainland. But we had no choice. There was just the one school, so we had to put up with Sgliugan and his green snotters and the cow-dung smell off Roderick MacPherson. Why couldn’t he clean his boots in the stream on the way, like everyone else? Snurfy Smith smelt of fried onions, so we all avoided him. We noticed that boys would never take their jumpers off. Not even on the hottest summer day. Or when they were soaked wet with rain on the way to school, they’d just sit shivering and sweating in their woollen jerseys, steam rising off them like cattle in a byre. As if they had something to guard.

At home, Duncan and Fearchar were like that too. Mam had to battle to get them to use soap morning and night. It was as if the smellier they were the more manly and grown-up they thought they’d be. There was one boy called Murdo MacInnes who was different. He smelt okay and spoke nicely to me and Dolina. All he was really interested in was the fishing, so whenever we asked him to play with us it had to be a game involving boats. He’d have to be the skipper with a cap on his head (one of his socks) and we’d be the crew hauling in endless lobster-creels. According to Murdo, if you didn’t know fishing you didn’t know anything. He had a Swiss Army Knife which he was always trying to impress us with, all blades and daft screw things. When he grew up he became a renowned trawlerman working out west as far as Rockall.

Some of the older girls were chasing each other across the playground; some standing, looking around, waiting for someone to be their friend, which never happened just like that, because friends are long made and forever, and if you didn’t have a friend by the time you were in Primary Seven you never would. So they said, though it wasn’t true. There’s nothing in the world like having true friends. Ones that like you and aren’t just pals because their parents told them to pity you or admire you or because they’re related to you or something. Someone you can tell your worst things to and they won’t correct you. It took me ages just to listen.

Bets Dolina will be behind the shelter again, I always thought. And Peggy, crouching behind the bicycle-shed. Katie was unpredictable. And unfair. She always needed to be first. Talk about cheating! She could be anywhere. Even inside the school, which was out of bounds during playtime. Well, she could stay there. I wasn’t going to get into any trouble going inside looking for her. She would just lie anyway, saying she’d gone inside to use the toilet or get a book or some other excuse. The lying toad, because lying was cheating and almost as bad as stealing. And she had no shame! When she did cartwheels she went round and round and round, not caring that everyone – even the boys – were seeing her knickers and bum. At least we did it over in the girls area. You just tuck your skirt into your bloomers and you can then cartwheel across the world if you want to!

And besides, she thought she was cleverer than all the rest of us. Told us one day she was writing a story.

‘A proper story,’ she said. ‘For grown-ups. Lots of words with no pictures, cos they’re just for babies who can’t read.’

Smartypants. What was the point of a story without pictures? Even where there were no pictures, weren’t the words themselves, words like ‘sea’ and ‘blue’, pictures? She wasn’t half as smart as she thought. Katie ended up ‘writing’ sure enough, as a secretary in some lawyer’s office in Fort William. And then the bell rang and the game was broken.

But the game with the birds never broke. I always wanted to be a bird, but they never wanted to be me. I couldn’t hop long enough or jump high enough or sing like them or make a nest up high or anything. They pecked in the little sandy pools while I tried various ways of getting near them, though they were reluctant to come near me, even when I put crumbs into the open palm of my hands and sat still as a stone. They might think I wasn’t a danger then. Which I wasn’t. But I never convinced them. Because, at the end of the day, I wasn’t one of them, and they didn’t care for me as much as I cared for them.

So at first I ran as fast as I could, but they always ran faster and rose and wheeled off into the air. I tried doing the same but could only jump about a foot. So then I tried creeping up ever so slowly and silently, but they just raised their little heads and hopped off as far again as I had come. The distance never got any smaller. It never does, which is why you need to persevere. Because one day a little robin sat on the palm of my hand, and I’ve never forgotten it. He had such brown eyes. Usually they perched for no more than seconds on a bit of wire or on top of a fence-post. Staying still was boring for them, I suppose. Fearchar told me that pigeons could travel at 90 miles an hour when they were delivering post, which was really fast. Much faster than Roddy our postman who pushed his parcels along on his old rickety bike. Honestly, the snails on the road were faster than him!

Mam moved slowly, like the summer stream, yet everything she did happened quickly. I’d spend ages with her mixing dough or threading wool on to the spool, yet next thing the loaf was steaming warm and a scarf made. I loved her more than anyone and anything else in the whole world. I miss her terribly. She never flew off like the birds. It was the sacred way she did everything, whether washing her hair or sewing a button onto Dad’s shirt. It’s as if she wasn’t doing them but unveiling them. She handled things as if they could vanish at any moment. Loosely, so that they had freedom to disappear if they wanted. I see that in you too, in the way you speak, without any malice. Mam always said that spite was like a knot in the thread. It spoilt the best work.

Mam loved combing my hair and always sang as she did it. When she mixed dough for bread, the flour rose into the air in clouds and I tried to catch the specks as they slowly tumbled back down into the bowl. I never could. She cooked everything slowly, saying the food was like the sun, needing time to rise, shine and set.

‘That way it gives you all its strength. Speed only extracts the goodness out of it.’

We never held hands, yet we were always touching.

‘Hold it this way, Annie,’ she’d say as she guided me through the stitches. I always loved the way she said my name. Annie, with her tongue caressing the letters nn. ‘Purl the wool on here, then loop the needle round this way. Look, Annie – see,’ her palm resting lightly on the back of my hand, guiding the needle as if it was a fish diving for worms and rising for air. Her hands were scarred and rough from work.

Mach’s a-steach.

Leum am breac.

(In and out,

Leapt the trout.)

Later on, when I was teaching my own children how to knit, I also used the old trick of turning a chore into a chant:

In through the front door,

Go round the back,

Out through the window,

Off jumps Jack!

I wonder if Aonghas can still knit, or whether he’s put that behind him as a childish activity, like all other things? Though everything clings on, the way the mist lingers in the glens though the sun is shining and the skies are all spotless and blue.

I listened to the smooth click-clacking of her needles downstairs as I drifted off to sleep every night. I always knew when things were going well because the sound was soft and smooth. When a stitch was dropped or a mistake made, the needles made a sharper, quicker sound.

Mam birthed the lambs in spring and after a while I was allowed to help. It all happened naturally. Sheep know how to give birth, but sometimes Mam sensed a difficulty, so she kept an eye on some of the expectant mothers. It’s a fine thing to be doing, caressing the mother sheep as the new-born lamb comes into the world. The trembling foot, and the little head first, and the lamb and mother’s tongue flicking in anticipation, then the mother licking every inch of the bloody lamb who struggles to get to its feet, reaching all the time towards the teats for food and life. The perfect training for me when I did my stint later on in the maternity ward!

Mam treasured everything she’d been given. Because of the givers. Her own mam’s wedding ring and silver brooch with a dove engraved in the middle. The letters and postcards Dad had sent her from these mythic, faraway places. Bahia Blanca. Buenos Aires. Vancouver. The white stone I gave her from the beach the day we had a picnic there and I learned to paddle. She kept them all by her bedside, and sometimes when I wasn’t well and slept curled in beside her I watched her hold them and smile. She liked brushing my hair, and as I snuggled in she ran her bony fingers through, unsnagging all the little tangles I’d made during the day. There was no end to them.

She also kept beautiful things in the sitting room, where people could see them. A painting of the hills made by the local vet, a lovely clock the Royal Hotel in Oban gave her when she left, and some of my shells and other odds-and-ends she’d gathered here and there. If Dad had his way, there would have been no ornaments or anything like that in the house – just the beds, a few chairs and a table, and he would have filled the rest of the space with spades and sickles and scythes and ropes and saws and scraps of wood and bits of engines. It’s as well Mam was there. She wasn’t fussy about things, but couldn’t bear them to be shabby. Folk’s houses and furniture could be untidy and messy, unkempt, old, rickety, even dusty and dirty – as long as they weren’t cheap and shabby. That was simply a lack of taste and unforgiveable.

The thing I enjoyed most was making butter with Mam. The two of us skimmed the cream from the milk into the wooden pail, then into the churn. We had two churns. One you turned with a handle, and one had a stick you pushed up and down. I liked the one with the handle best. You turned it ever so slowly at first, then faster and faster until your arms got sore. The more I turned the handle the thicker and creamier the butter became. I was allowed to stick my finger in and lick the thickening cream. The best bit was when our hands got all mixed up as we rolled the butter on the baking paper so that sometimes I didn’t know which were my fingers and which were hers.

Mam always sang as we churned the butter together and then moulded it into shape with the butter-pats. I liked the squishy sounds they made. You could make all kinds of patterns on the top of the butter so that it looked nice and fancy. I liked making swirls which were like flower heads. The butter always tasted better when it was a snowdrop or a primrose, which were Mam’s favourite flowers. She told me that the snowdrops had made themselves white because they’d seen the snow fall and wanted to be part of it while the primroses had seen the rising sun and made themselves golden yellow.

Mam was always working. She got things done. If not cooking, sewing, and if not sewing or stitching or patching, then feeding the animals, or milking the cows, or cutting the hay, or making sure our shoes were clean for school. She once made a lovely wee jacket for me from Dad’s old green corduroy trousers. When I pass old-fashioned clothes shops I think I see her in the window tidying up the display, checking the jacket lapel here, the proper crease of the suit-trousers there. So many things that need put right.

Songs were sung to pass the time, though the words and the melodies made magic happen. For what’s the point of words if they don’t change anything? You bless and curse and wish and hope and cry in songs. You wish for the impossible and make it happen by weaving a daisy-chain which ties everything together. Milking songs and herding songs and waulking songs and ploughing songs made work easier. As soon as the work was finished, the song ceased. Except it kept going round and round in our heads. Beautiful ringleted lovers appeared – and heartbroken women wept – as the milk squeezed out of the udder or as the cloth shrunk under pounding arms. I learned all the songs by singing them, again and again, with Mam. It was part of things, as natural as drawing breath, as necessary as walking to the well for water or to the shore for sticks. Amazing how you learn things better when you’re moving. Rhythm helps you remember. I tried yoga once, which taught me the very opposite. It never worked for me. I’ve known too many still, silent people, weeping inside. We could hear the dead crying down in the cemetery on quiet winter nights.

Some people liked working in silence, building small stone walls slowly and quietly as if they were asleep or in church. A noise might make the wall fall. Not even whistling. Which was odd, because whistling was one of the privileges of working outside. No one ever whistled inside. That was the work of the devil himself. James Thomson had whistled and next thing had two bumps on his forehead which disappeared as soon as he stopped. The boatbuilder Angus MacIsaac worked in an old wooden hut which smelt of candle-wax and paraffin-oil and whenever I passed I was almost lulled to sleep by the smooth sound of sawing and the soft blow of a mallet on wood, beating like a faraway lullaby. You never heard him, just his work tools. One day I saw him chasing after the postman, and it struck me he was the only grown-up I ever saw running.

I tried to tell Duncan and Fearchar about the songs.

‘Boring old things,’ Duncan said. ‘I hear far better ones on my transistor.’

Though I knew he secretly envied what I was learning. Thing is, I spent far more time with Mam. Duncan and Fearchar spent more time with Dad, who never sang. Hardly spoke really, apart from giving instructions or directions. As if words couldn’t say thoughts and needed to be grown like potatoes before they could be peeled or said. For it is one thing to think a thing and quite another thing to say it.

‘You move the handle that way.’

‘No. Not like that. The other way round.’ Sometimes we only understood what he said by working out what he didn’t say.

And yet Dad transformed when he told his stories at the cèilidh. It was as if he never then had enough time to tell everything he knew. His words ran like Thorro’s River in full flow, bubbling over with actions and descriptions. Each story was always told in the same way. He never used hand gestures. Just the words and pauses, that was enough to tell everything. As if the story was in the telling.

I don’t know how much that had to do with the fear of the unknown, as in the books I read, where strange lands were marked with the words ‘Here Be Dragons!’ Maybe the words and phrases in Dad’s stories were like ancient markings telling him which way to go, like one of those walks you can do in your sleep. I always try and find new walks to go on so that I can be surprised at every turning like when I was wee. Don’t believe it when they tell you that old people don’t want surprises too!

It’s best when you make your own markings. Like when you reach the bottom of the road from our old house the track turns rightwards towards the machair and then there’s a fork leading you down to the cemetery. But just before you reach it there’s an old broken plough and if you follow the furrow line, that will take you on down the familiar path to the shore. If you didn’t know to turn at the old broken plough you’d go in the other direction and end up in the bog, and sink. Dad’s words were like the immovable mountains after all, rather than like the tumbling waters. Outside the story, he was almost mute, in the same way that water is silent until it moves over a rock or weir. The ocean itself looks calm and quiet until you’re near it, when you sense its might.

So the boys became stilted too in public conversation, as if saying anything more than four words was burdensome, like writing a school essay about ‘My Favourite Thing.’ What a cheek! Imagine. That was a private matter between us and our best pals, not to be told to a teacher for approval and correction. As if Dolina or I would tell any grown-up what we were thinking. Perish the thought! Why should I tell a teacher or any other nosey adult what my favourite thing was, or what I did on my holidays? The boys were not quite monosyllabic, but their three commonest public words were Aye, No and Maybe.

‘How are you today Duncan?’

‘Fine.’

‘How’s school, Fearchar?’

‘All right.’

‘Are you coming out to play this afternoon?’

‘Maybe.’

Yet when they were together they talked endlessly. About football and puppets. The puppets only worked properly if you could suss out from the shape what they were about to do. Fearchar made football players out of them. The best goalkeeper ever was Lev Yashin who once saved three penalties in a European Cup match against Dinamo Zagreb, even though his own team, Dynamo Moscow, still lost 2-0. I heard it so often from them that the teams and scores remain there like a poem learned by heart. I find myself wandering down the road reciting ‘I must go down to the seas again to the lonely seas and the sky’ and the best of it is that I don’t care anymore who hears. You reach an age where any sound is welcome.

And the most important thing about making a puppet are the proportions, Fearchar said. If you’re making a human figure, the best way is to divide the body into eight equal sections, a head itself measuring from the crown to the chin. The next section takes you from the chin to a line drawn across the nipples, and from there to just above the navel, then to the hips, the middle of the thighs, to just a little below the bend of the knee, to a point a little below the calf and from there to the base of the heel. It was like some kind of magic formula, or the Hail Mary. It only worked if the words were right.

‘But everybody is not the same size,’ Duncan argued.

‘Doesn’t matter,’ said Fearchar. ‘I’m not talking size, I’m talking proportions.’

‘Huh!’ mocked Duncan. ‘Proportions! That’s a big word for you. You don’t even know what it means. It’s just something you read in that booklet.’

But Fearchar knew so many other strange things. That if you kneel down you are a quarter of the height you are when standing up. That the face from the hair-line on the forehead to the point of the chin is equal to three nose lengths!

‘How do you know?’ Duncan asked. ‘Have you measured every nose in the world? Pah! You haven’t even measured my nose.’

‘Can I?’ asked Fearchar.

And it was true. The length of Duncan’s face from the hair-line on the forehead to the point of the chin was equal to three times his nose length!

‘But what if I had longer hair? Or shorter?’ said Duncan. ‘Or a bigger nose. Like that corker Robert has. It wouldn’t work then, would it?’

‘Would so. It’s nothing to do with the length of your hair, but with the hair-line. Where the hair starts on your head. Any old idiot would know that.’

Duncan was lying on his bed and flung a shoe at him to shut him up. If he said anything else Duncan would hit him. But Fearchar went quiet. He knew the signals. And anyway, surrender would hurt Duncan more. Everyone liked Fearchar because he was pals with you even when he had nothing to gain by it.

I could hear the boys talking next door from my own room, though I couldn’t exactly make out what they were saying. Well, I could if I really wanted to, which I didn’t. Why would I? Everything is much more interesting imagined than spoken. But I knew the tone of their voices so well. Duncan’s had suddenly grown lower, like the drone of a bagpipe, while Fearchar’s voice was still that of a boy. Without hearing any words I could fathom it all. The silences, and the length of the silences, told most. Agreement. Disdain. Peace. Anger.

My own voice was changeable. I could make it go high or low whenever I wanted. My best voice was being a bird: I could do them all. Up and down like a swallow, whistle like the oyster-catcher and my all-time favourite, wheeping like a peewit. Curracagan we called them, because that sounds like the song they make when they cry out in the heather. Kak-a-ka-kaa. Four syllables. It wasn’t that difficult really – I just turned their cries into vocables as my mother did with the songs she had about the swans and the seals. Everything can be imitated, even though you don’t often then turn into the thing you pretend to be. Though Dolina could, folding herself into a swan. You need to be careful, however. So many people had turned into crows and toads from singing deliberately out of tune and slithering along the ground instead of walking properly. Dolina said crows and toads were just enchanted people doing penance and would become good and kind people again after a thousand years.

It’s an amazing thing to listen before you speak. Then you’re hearing for the first time. They say the dog yaps and the kitten meows and the cow moos and the sheep goes baaaa, although that’s not what I heard. Maybe our animals made noises in Gaelic? Ha! Sometimes I’d coorie in with Dìleas the collie, and he breathed ever so slowly, making a noise that sounded like capooh, and when I stroked the cat he purred, and the cow grunted and the sheep made a clacking noise as they munched away at the grass. For you need to tell someone what you’ve seen or heard, even if you’re only a sheep.

I asked Mrs MacPherson about it once.

‘Do the birds speak to one another like we do?’

‘Of course they do. Just watch the swallows – how they warn one another if someone is approaching, and how the doves sit in pairs. For company. It’s obvious they have their own language, to tell things to each other. Swallows speak to swallows and eagles to eagles, but eagles never speak to swallows and swallows never speak to eagles. Otherwise there would be no secrets, and the smaller birds would be in terrible danger from the bigger birds, and from us. You must have ways of telling and keeping secrets. And only the small birds sing. No bird of prey was ever given the gift of song.’

I liked Mrs MacPherson because she was interested in me as a person. In what I liked or didn’t like and what I felt. Most of the other older people only ever asked me how Mam and Dad were, as if I was just something, like a watch, that told about something else. Maybe that’s why I’ve never worn a wrist-watch. I just carry Dad’s old pocket-watch in my bag. It’s got a beautiful carving of a griffin on the face. It doesn’t work, so it doesn’t tell the time, which is even better. Mrs MacPherson looked after Hazel, who was a special girl. Her Mam was always unwell and no one knew who her Dad was, so she spent a lot of time near us at Mrs MacPherson’s. She sometimes danced out in the moonlight singing happy songs as she moved about the garden. ‘First the heel, then to the toe, that's the way the polka goes.’

James Campbell was the man who made the dream of the airport come true. Which may have been why he was regarded by some as the bad fairy who had spoilt things by changing them. When old people died he bought their houses and did them up and sold them. I’m not sure if I ever told you about him. He was much older than us but not as old as Mam and Dad. I was afraid he would silence the birds, because he couldn’t speak or understand their language and disliked everything he wasn’t in charge of. Even though he used such sweet melodic words himself, comparing planes to the elegance of the golden plover in flight and to the power of the eagle in its ascent and descent! I suppose he might have been a bird-catcher in the bad old days. Those guys who used to go round the place snaring larks and linnets to sell to gentry to put in cages. Sometimes it’s hard to believe how wicked people can be.

‘Aeroplanes are mere birds with the power to carry humans,’ he said. ‘Just an extension of nature. There are beings, and I count myself among them, to whom the skies matter more than the land and the earth. They even make the same sound. Wee-ah-wee!’

‘Don’t worry,’ Mrs MacPherson told me, ‘he’s not God. And though devils can fly, Campbell’s got no wings. And even if they did, they would be clipped. And remember, darling, that if the cows and birds are all evicted by him, they will find other places to graze and sing. You’ll hear them all your life, Annie, because you’re hearing them now.’

It was as if everything was still to be learnt, rather than already known. It took me ages, for example, to realise that birds fly by the wind as much as by their wings.

Strange to think now that electricity and aeroplanes were regarded then by some people as great dangers. Of course they were – we could all see that, in a way – but then again so was everything. You might fall into the well. A bull could gore you as you crossed a field. If you went up the hill the water-horse might get you. Lachlan MacIntosh had been drowned swimming in the sea because he refused to listen to anyone who told him it was dangerous. People fell into ditches all the time, stumbling their way home from the pub in the dark. They went there for company, to find someone to talk to. It was strange to want to be in company, and even stranger to want to be alone, so no one ever won.

Sometimes the more beautiful a thing was, the more dangerous it was. Martha in the next village was drowned trying to pluck one of the lovely purple water-lilies from Loch Challainn. She was so stupid, because we’d all been warned so often not to crawl out through the rushes to try and get them. They were so tempting though, floating ever so gracefully in the water. There were white and yellow ones as well as purple ones. We plucked the ones along the water’s edge and then took the sticky bits off and put the blossoms in our hair or sometimes in a vase in the house, even though Dad said that was unlucky. Maybe things should be left where they are anyway. We were brought up believing we should always leave things as we found them. Maybe the owners haven’t gone far – just popped out for a walk over the river a hundred years ago and will be back before evening.

Truth was that danger lay everywhere, and the arrival of electricity and the development of the local airstrip seemed to me no more dangerous than cycling downhill or when the first horse and cart or car arrived, or when the first steam boat sailed between the islands, billowing smoke out and up into the heavens. And besides, it was exciting: who didn’t want light at the flick of a switch, and who didn’t want to fly high in the skies like a beautiful bird? We could do everything instantly. When we wanted. Not when someone else decided. Be immediately on the other side of the globe, faster than on any imaginary magic carpet or any wick of straw that these daft old people at the time talked about. Who knew anything about an energy crisis as the pot bubbled on the peat stove? You can’t fathom the future by what you don’t know. You only fear it if you haven’t bothered to cut enough peats to last you through the whole winter.

Old Murdo said that the electric was just like sheep and had to be controlled.

‘It’s to do with electrons,’ he declared, ‘which stray about all over the place like sheep. But when a stick is applied to them, you can steer them along just fine. That’s just the same thing a good dog does when you whistle him to lead the sheep to the fank.’ He imagined everything worked the way sheep did.

Sometimes it looked as if the sheep were running around playing chase-and-catch in the fields, but it was just Murdo and his dog gathering them all in. Despite his daft opinions, Murdo was thought very highly of because he had the best collie in the village. Intelligent, lovely to look at, with a perfect white diamond patch just above her nose, and a joy to watch working as she sat and crept and gathered without even a whistle from Murdo. I think Murdo was in love with his dog and his dog was in love with him. She was called Polly. We called her Pretty Polly and used to sing ‘Polly put the kettle on’ as we walked with her to school. As soon as we arrived at the school gate and finished the song, she barked once and then ran back home to Murdo.

We were conscious of a discontent, especially among some of the older folk, who feared that the imminent arrival of electricity would change everything and that the little they had would be taken from them. Things would be different, and not as they had been anymore. Already, things were getting faster and bigger and stronger and better. Old Murdo proved it by telling everyone that while a cart only had two wheels the new cars had four, so they could obviously go twice as fast. Though Mùgan reminded him that he’d seen kangaroos in Australia which, though they only had two legs, could still run faster than any four-legged sheep or cows he’d seen ambling lazily around our fields.

Who cared at the time? For life was all change, and Dolina and Morag and Katie and Duncan and Fearchar and I liked fast things. Even as they stood still, in those long, endless days. We all dreamt of going fastest downhill without any brakes. Angela Smith held the record, though we all knew she’d cheated by taking off her outdoor clothing and shoes and doing it in just her vest and pants so that she’d be really light. There was no rule against that, but it wasn’t really fair because no one else was daft enough to go next to naked in public.

Every day brought something new – Peggy making a new doll out of a wooden clothes-peg or Dolina who always picked the nicest flowers on the way to school and stuck them in a different way in her hair every day. Some days in a bunch, some days one above each ear, some days in a sort of hoop round her head. And then it was the best time of year again – time to pick the daisies and make chains. Dolina was always the best at it, splitting the stalks with her teeth and then weaving them into each other until they were just the perfect size to hang round our necks as decorations, though sometimes we all ganged up together and made one long chain that went on and on forever. Once, we made one that stretched from the school gate all the way across the playground, right over the wall and on over on the other side to the pond, and though the boys wanted to break it, none of them dared, for they knew that was bad luck and whoever broke it would die.