Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

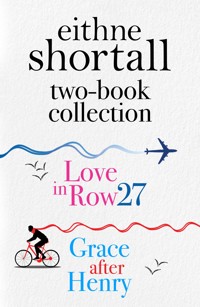

Love in Row 27 What happens when Cupid plays co-pilot? Still reeling from a break-up, Cora Hendricks has given up on ever finding love. For herself, that is. To pass the time while working the Aer Lingus check-in desk at Heathrow, Cora begins to play cupid with high-flying singles. Using only her intuition, the internet, and glamorous flight attendant accomplice Nancy, Row 27 becomes Cora's laboratory of love. Instead of being seated randomly, two unwitting passengers on each flight find themselves next to the person of their dreams - or not. Cora swears Row 27 is just a bit of fun, but while she's busy making sparks fly at cruising altitude, the love she'd given up on for herself just might have landed right in front of her... Grace After Henry Grace sees her boyfriend Henry everywhere. In the supermarket, on the street, at the graveyard. Only Henry is dead. He died two months earlier, leaving a huge hole in Grace's life and in her heart. But then a man who looks uncannily like Henry turns up to fix her boiler one day. Grace isn't hallucinating - he really does look exactly like Grace's lost love. Grace becomes captivated by this stranger, Andy. Reminded of everything she once had, can Grace recreate that lost love or does loving Andy mean letting go of Henry?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 896

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Also by Eithne Shortall

Love in Row 27

Grace After Henry

Three Little Truths

It Could Never Happen Here

Eithne Shortall studied journalism at Dublin City University and has lived in London, France and America. Now based in Dublin, she is editor of the Home magazine at the Sunday Times Ireland. Her debut novel, Love in Row 27, was a major Irish bestseller, and the follow-up, Grace After Henry, was shortlisted for the Irish Book Awards and won Best Page Turner at the UK's Big Book Awards. Her third novel, Three Little Truths, was a BBC Radio 2 Book Club pick.

Published in eBook in Great Britain in 2021 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Eithne Shortall, 2017, 2018

The moral right of Eithne Shortall to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novels in this bundle are entirely works of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 646 2

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

For my granny, whom I love.

CONTENTS

One

Two

Three

Four

Five

Six

Seven

Eight

Nine

Ten

Eleven

Twelve

Thirteen

Fourteen

Fifteen

Sixteen

Seventeen

Eighteen

Nineteen

Twenty

Twenty-One

Twenty-Two

Twenty-Three

Twenty-Four

Twenty-Five

Twenty-Six

Twenty-Seven (A)

Twenty-Seven (B)

FW: Follow-up Email: Security procedures going forward

Marsha Clarkson, Chief Executive<[email protected]>

Jul 23 at 11:11 p.m.

To: All Staff

Thank you all for attending this afternoon’s briefing. The key points are clarified below:

While our recent security scare was a false alarm, it did highlight certain weakness in our operations. In consultation with the Home Office, we have agreed to cease self-check-in until our security system can be safeguarded.

All check-ins across all airlines will now be done manually by staff. Passengers will have to present, in person, at their check-in desk with reference number and identification in hand. Extra staff have been added across the board – so there is no need for concern about personal workloads. The airport authority is helping with costs in this regard.

The self-check-in kiosks have now been removed and placed in storage. Internet check-in will be disabled. We have been advised the restrictions could remain in place for up to one year. Staff will be updated as and when information is available.

As of tomorrow, we return to the old days of air travel, and we’re going to do so with a smile. This is an opportunity to put customer service back at the centre of what we do. I encourage you all to go above and beyond for our passengers.

Marsha Clarkson

Chief Executive, Heathrow Airport Authority

<<DO NOT RESPOND TO THIS EMAIL>>

ONE

The self-check-in embargo had been in place for eight days when a woman with multiple haversacks presented herself at the Aer Lingus counter and accidentally began the greatest love story of Cora Hendricks’s life. A story that was all the more appealing because Cora didn’t have to be its star. At this point in time, in matters of the heart, she could just about handle a supporting role.

It was the last day of July and she had been with the airline less than a month. Barely enough time to get her feet under the check-in counter before the embargo threw all of Heathrow Airport into disarray. She was making her way through a never-ending line of increasingly agitated passengers, and doing her best to act like she had everything under control, when the luggage-laden woman approached and placed a small recording device on Cora’s desk.

‘It’s for my podcast.’ She flicked a switch at the side of the microphone and let her tangle of bags drop to the pristine airport floor. ‘Don’t worry. No one will hear you. I’ve been recording these things for almost a year and I never manage more than three listeners.’ The woman buried her head in an overburdened tote bag and rummaged for her passport. ‘And she says she’s not, but I know my mother is one of them . . . Found it!’

Cora took the dog-eared passport and began to enter the woman’s details into her computer. ‘What’s your podcast about?’

‘It’s a book travel show. I’d always said to myself, “Trish: you need to travel more and you need to read more.” So then when my boyfriend broke up with me – totally over it, don’t cry for me Argentina – I decided to see it as an opportunity. Get out there and do what I always said I would.’

‘Travel and read?’

‘Precisely. And I don’t care if nobody’s listening. I’m forever losing things and forgetting things, so it’s just good to have a record. This’ – she tapped the mic – ‘is a sort of oral history of a liberated gal.’

‘That sounds great,’ said Cora, meaning it. Her old self would love to have done something similar but when Cora had been ‘liberated’ – to use the most euphemistic of euphemisms – she’d taken the more clichéd route and just fallen apart.

‘I read a ton of books, talk about them on this, and, if they’re any good, I travel to where they’re set. Just Book It is the name of the show – if you want to be my fourth listener.’

‘Seat 27B, departing through Gate B,’ said Cora, leaning into the mic as she returned the woman’s passport with a boarding card inside. ‘So what’s the book that has you going to Belfast? Some thriller?’

‘This one’s actually a bit of a cheat. I’ve been reading the Game of Thrones series since I started the podcast. My ex hated fantasy so initially I picked them out of spite, but now I bloody well love them! Anyway, since Westeros isn’t actually a place, I thought I’d go to Belfast. It’s where they record the TV show so, you know, the nearest thing.’

‘Never been into science fiction myself.’

The woman paused. ‘It’s fantasy.’

‘Oh right.’

‘No science involved.’

‘I didn’t realise.’

‘Completely different genres.’

Cora managed to break eye contact. ‘Well I’ll definitely give the show a listen.’

‘Thanks!’ The woman picked up the recorder and shoved it and the boarding pass into one of her many haversacks. ‘You’ll probably be the only one!’

Sitting on the Tube six months later – six months to the day later – Cora recalled how she had known instantly that there was something special about the podcast woman. Her energy and attitude were exciting. Cora, who had always been intrigued by the lives of others, knew there was more. So when, an hour or so later, a crinkled copy of George RR Martin’s A Game of Thrones landed with a thud on her counter, the check-in attendant was only slightly surprised. It had the feeling of fate.

‘Belfast,’ she said, raising an eyebrow at the curly haired book owner. ‘I presume?’

The young man looked abashed. ‘Do you get a lot of Game of Thrones fans flying to Northern Ireland, then? I should have known I might be one of many,’ he said, handing over the necessary documentation. ‘I went to New Zealand after the first The Lord of the Rings film, and the hostels were half full of British fans.’

‘You went to New Zealand because of a film?’

‘Well I couldn’t exactly visit the Shire.’

Cora looked at the gangly man and somewhere in the blacks of his twitching eyes, everything fell into place. Her mind raced back to the podcast woman, enthusiastic and frazzled from the frayed ends of her scarf to the tips of her static hair. She looked at this man, with his awkward smile and equally carefree aesthetic. Cora scanned his fingers – no wedding ring – and glanced again at the well-thumbed tome still sitting on her desk. Of all the airports, in all the land – finally a purpose had walked into hers. ‘And tell me,’ she said, trying not to sound too eager. ‘Would you call Game of Thrones fantasy?’

The man gave an excited laugh. ‘Does Bilbo Baggins have hairy feet?’

‘Em . . . yes?’

‘Of course he bloody well does!’

Coming to the airport hadn’t been a career move for Cora, so much as a lifeline. She had returned from two years in Berlin, crawling out of a relationship that left her heart slumped in her chest and her insides jumbled up. It felt as if someone had grabbed her core and shook so hard that everything became dislodged. Cora came home thinking she’d like to help people but all the obvious careers – nursing, social work, counselling – seemed too big, too important, and she couldn’t be sure she wouldn’t mess it up. She thought Aer Lingus would give her time to realign, to get her insides back in place.

How had it taken her a week to see what was right in front of her? The embargo was a gift: no more online check-ins or kiosks; now everyone had to approach the desk. Their destiny – or at least where they sat for a couple of hours of air travel – was in her hands. The potential to play Cupid was endless. This was it – this was her chance to help people.

Cora scanned the seating plan for the flight to Belfast and found that 27A, the seat right beside the podcast woman, was still unoccupied. Cora assigned it to the curly haired man and handed over the ticket, another question occurring to her. ‘You’re not travelling with a significant other or—’

The man blushed. ‘I’d need to have one first, wouldn’t I?’

‘Perfect! You’ll be in 27A. Departing through Gate B.

Have a great flight!’

As the early morning Tube rattled through the suburbs of South London, occasionally rising from the darkness of the tunnel into the darkness of the winter morning, Cora felt an involuntary thrill of delight. Happy anniversary to me. Six months since her commute had been given a purpose. Six months since her job behind the check-in counter at Heathrow went from a reasonably well-paid distraction to a meant-to-be vocation.

Most of what she needed to know about her matchmaking candidates could be found on their flight information or through Internet searches. There was as much information about people on social media as there was on any dating site. And in repayment for free standby flights, her younger brother Cian had created a computer program that allowed her to quickly highlight all passengers whose marital status was ‘single’.

The Tube pulled into Heathrow and Cora alighted with the remaining passengers. She stretched out her back, ascended the escalator, and resolved to seek out the sun when it finally showed its face. There was a bench behind the taxi rank where she liked to have her lunch and watch as complete strangers negotiated sharing cabs into the city. She liked to imagine the lives they led and the things they might talk about as they sped away together.

Cora had always thought the best thing about flying was the possibility of who might be sitting next to you. Waiting at departure gates, she would look around and think which of her fellow passengers she’d most like to be seated beside. Imagine meeting the love of your life 40,000 feet above ground. The idea was enough to make her swoon. These days, Cora was in recovery mode and such happenstance was not of personal interest. But for everyone else the possibilities were endless, and now she was in a position of power.

The staffroom was full of morning crew, brewing coffee and discarding woollen layers. Cora hadn’t been outside since entering Finsbury Park station at 5 a.m. but still the cold lingered on her finger tips. She’d always had poor circulation. Cold hands, warm heart, Friedrich used to say, and Cora dismissed the thought of him as quickly as it had entered her head. She punched the combination into her locker and opened the metallic door just as Nancy swung out from behind it, her perfect face shattering Cora’s revelry.

‘Coo-coo, Cupid,’ said the air hostess, one hand on the locker, the other on her narrow waist.

Nancy Moone had started with the airline at the same time as Cora and accidentally become her best friend. It’s a fallacy that you can choose your friends. It’s all down to geographical proximity. School chums are limited to those living in the same catchment area, and work friends are whoever happens to get the locker next to you.

‘Alright, Nancy,’ said Cora, kicking off her trainers and sliding her feet into the required work footwear. ‘You’re very chipper for this hour of the morning.’

‘You would be too if you’d spent the weekend with me mam. All my children trying for babies, all except the one with a uterus.’

‘She did not say that.’

‘Well, no. But that was the gist of the entire visit. Look at my fingernails, look. Bitten away to nothing.’

Nancy had always wanted to be an air hostess. Her childhood was spent commanding her brothers to sit one behind the other on the stairs of their Liverpool home while she placed a sheet of tissue paper and a small handful of raisins on each of their knees and politely reminded them, when they were done, to store their trays in the upright position. When the Moone family went on their first sun holiday to Benidorm, twelve-year-old Nancy asked the woman who gave the safety demonstration for her autograph.

Were you to see the twenty-seven-year-old Nancy out of context and out of uniform, you’d probably still guess what she did for a living. Blonde, shapely, and always immaculately made-up, she was like one of those poster girls for the early days of air travel.

‘How about your weekend? Any eligible fellas in nice designer suits? Is that what’s giving you the big, dreamy smile?’

‘Hardly,’ said Cora, her voice muffled by the pins held between lips as she scraped back her thick dark hair.

‘Soon you’ll be old and grey and saggy, and you’ll regret not having listened to your mate Nancy.’

‘And what exactly is it you expect me to do with my pert, pigmented self in the depths of Cornwall?’

‘You were at a wedding! A bit of flirting never killed anyone. You’ve got to shake off the cobwebs. It’s not like riding a bike you know: you can forget.’ Nancy, who had colonised Cora’s mirror, held her mascara wand aloft. ‘Use it or lose it. Trust me, Cupid, I’ve got your best interests at heart.’

Nancy was the kind of woman over whom men happily made fools of themselves, but the air hostess took a special interest in Cora’s love life. If her friend was going to turn everyone else’s romance into a project, then Nancy was going to make Cora hers.

‘It’s good to meet a cross-section of people,’ she continued. ‘God knows you won’t meet anyone here; big-headed pilots and the few members of cabin crew who are men, well, they’re not interested in women – no matter how modest your bosom might be.’ Cora frowned and pulled at her jacket. ‘You have to get out there.’

‘What about that BA pilot you were seeing – Paul, was it?’

‘Well that was different,’ breezed Nancy. ‘He was unfeasibly pretty. Anyway, that was my first and last flyboy. Best to have a bit of space between work and pleasure. Was there no one at the wedding at all?’

‘Oh, I’d say about 120 guests.’

‘Ha ha, Cupid. You know what I mean! No man who took your fancy? Nobody of interest? Tell me there was at least a singles table!’

There had been plenty of people of interest and all in a romantic sense, but not in the way Nancy meant. Not of interest to Cora personally. Weddings in general didn’t do much for her. No matter how good friends she and the happy couple might be, Cora’s interest in the bride and groom disappeared once vows had been exchanged and the bouquet thrown. As a child she had lost interest in soap-opera characters as soon as they married. Their storylines became markedly less exciting and their potential diminished. At twenty-eight, she felt much the same about real life. Ring on finger, paperwork signed equalled game over – going into sleep mode. Cora considered herself a diehard romantic and as far as she could tell weddings, with their fixed schedules and months of planning, had very little to do with romance.

There was, however, one point on which Cora and Nancy agreed: a singles table made nuptials worthwhile. Not because Cora might find herself a convivial man, but because this was the one table in the room with possibilities. On a day dedicated to tidying lives away, this was where something could still happen.

At Saturday’s singles table – the bride was a friend from Cora’s art history class at university – there had been eight contenders. Seven, if you excluded Cora, which she did. Cora was the facilitator.

Cora tried her best with what she had. She suggested another uni friend swap seats with her in order to talk to a pair of brothers from Walthamstow. But the men only seemed interested in giggling with one another. Another woman was an artist whose work the bride had recently curated. ‘Post-impressionism,’ she told Cora. ‘My interest is in the spaces between the paint. That’s where the truth is really being spoken.’ She tried to get the artist closer to a cousin of the groom, but the cousin was a level of obnoxious that involved clicking his tongue when any woman under fifty came into his line of sight and spending the rest of the evening nodding rhythmically as if Jimi Hendrix’s ‘Foxy Lady’ was sound-tracking his wedding experience. In the end, the only thing Cora’s awkward shuffling achieved was to disorientate the waitress and leave everyone with the wrong main course.

‘You have your own love life to look out for too, Cupid,’ said Nancy, who had finally relinquished the locker mirror.

‘So you keep saying,’ replied Cora, slamming the metal door shut. ‘But that’s just not half as fun.’

The bell went, indicating the next round of check-ins. Cora and Nancy vacated the staffroom, Nancy heading for the boarding gate, and Cora towards the desks.

‘Good weekend, pet?’ asked Joan, heaving herself onto the stool behind a second check-in desk. The older woman, who sat beside Cora for most of the week, was back from her pre-dawn smoke break. Aer Lingus hadn’t permitted staff to abandon their posts for the ingestion of nicotine in more than two decades, but Joan Ferguson paid as much attention to that as she did the requirement to produce a sick cert or to stop referring to cabin crew as ‘trolley dollies’. Joan had been with the airline for thirty-three years and she was going to operate within the exact working conditions she’d signed up to until the day she retired.

‘Oh you know; another wedding, another hangover.’

‘But it was your anniversary, Joan! Jim get you anything nice?’ Joan threw her a look. ‘Jim get you anything?’

Joan’s husband had been in the bad books since he moved a flock of pigeons into their tiny Hounslow garden two months earlier and Joan’s clothes line had become a shrine to bird excrement. Having reached legal retirement age, Jim had been forced to leave the local bookmaker’s where he’d worked all his life. He was devastated – torn away from the horses, the dogs, the various hot tips. Joan said he was the only man who had more money when he was out of work. The pigeons had been a leaving present from a bunch of regulars, the same lads he did the table quiz with at the Goose Tavern.

This weekend had signified the final chance Joan was giving her husband of thirty-one years to make amends. If he bought her a decent gift (a kitchen appliance from a car boot out the back of the Goose did not count), and took her for dinner in one of the two ‘special occasion’ restaurants in Hounslow without doing his usual martyr bit of refusing to open the menu and just telling the waiter ‘whatever’s cheapest’, then, and only then, would she forgive him the birds and their relentless bowel movements. Naturally, Joan hadn’t conveyed a word of this ultimatum to Jim.

‘Useless,’ began Joan, redistributing her body weight across the stool as she settled into the story. Joan loved to complain. She was a fatalist and all the happier for it.

‘The bugger phones me Saturday night from the Goose asking if I’ll call a Chinese in for him. On his way home, he says. Sweet and sour chicken – and see if they’ll throw in some crackers. And there’s me still thinking we might go out, not to Il Giardino at this point, we’d have to book – that place is a bit posh anyway and Jim still hasn’t gotten his tooth fixed – but to Alistair’s. So I went out back, opened all those stinkin’ coops, set the birds free and headed off to Maura’s. I told you about Maura? The one who beat the breast cancer only for her sister to be diagnosed? Well, anyway, I get home three hours later expecting an apology, or at least that he’d be fuming at the loss of his lovely pigeons – and there he is, Lord Muck, asleep on the sofa, sweet and sour on his lap and a can still in his hand. I go out back and there are the ruddy chickens—’

‘Pigeons.’

‘Pigeons. All back sittin’ in their cages, just looking out at the open door.’

‘I suppose they’re homing pigeons.’

‘I bloomin’ realise that now, Cora! I went in, woke him up and gave him an earful, then stormed off to bed. Next morning he makes me egg and soldiers. Take what I can get, I suppose.’ Joan blew the disappointment through pursed lips, and turned from Cora to face her first passenger of the day. ‘Where are we flying to today, love?’

Joan had met Jim when she first came to Aer Lingus. She had started the same year as Cora’s mother. They were best friends, or at least they had been when Cora’s mother still worked for the airline. She didn’t get out as much any more.

‘How is Sheila?’ asked Joan, as if reading her mind, the early check-in sent off with her ticket for Madrid. ‘Did you see her at all this weekend?’

‘I was in Cornwall all weekend but I’ll pop round tonight.’

‘Must get in to see her myself.’

Sheila Hendricks had been in a medical institution for several months now. Cora and her older sister Maeve visited every week and Cian, who had high-functioning autism and conveniently played the Asperger’s card whenever any uncomfortable situation arose, went in occasionally. Sheila had gotten Cora the job in Aer Lingus, one of the last fully coherent things she did. She pulled some strings and the daughter was in, just as the mother was starting to fade out. Cora felt a sudden wave of guilt that she hadn’t been to see her in almost a week. She really would go tonight.

She ran the passenger list for that morning’s Edinburgh flight through her brother’s computer program. The list included a few men in their mid-twenties – too young to have a life partner, she hoped, but old enough to be open to one. She inserted some names into Facebook. Profile pictures (selfie with girlfriend on mountain top/in front of Eiffel Tower) and relationship statuses disqualified several candidates immediately.

Then came Andrew Small: single, twenty-two, a Londoner living in Edinburgh. His photo albums showed a handsome young man with thick black hair and the ‘about me’ section said he was from a sink estate near where Joan lived but was currently studying politics in Scotland. Andrew Small would do nicely. Heterosexual, Cora was fairly confident, thought that was always a potential pitfall.

The first few check-ins were of little interest: a lot of older commuters and a returning, bleary-eyed stag party. A young woman approached the desk, passport ready to be handed over. Cora assessed her quickly: bright tights, dip-dyed hair, canvas backpack. A possibility.

‘Work or pleasure?’

‘Just a day trip. Surprising the boyfriend!’

Blackballed. Two further possibilities were disqualified – the first for being too quiet to even engage in in-flight conversation and the second for living in Leeds. Cora was aiming for undying love, so geography was a factor.

But third time lucky. Cora knew it when she saw her – the perfect stranger for Andrew Small.

‘Hi,’ said the young woman, tall with straight hair that fell below her shoulders and a blaze of freckles across her nose. She swallowed a yawn and laid her passport and a printout of her flight number on the counter.

‘Work or pleasure?’

‘Em, work,’ said the girl, who wore a T-shirt with the name of a band Cora had never heard of, and skinny jeans. She smiled. ‘Glad to be going home.’

Cora flicked open the passport: Rita MacDonald, Scottish, twenty-three, well-travelled.

‘Well, Rita,’ she said, closing the passport and handing it back with the boarding card inside. ‘You’ll be in 27A.’

‘A window seat. Ace.’

As Rita wandered off towards the boarding gate, passport slipped into the leather bag slung over her shoulder, she was replaced by Andrew Small. He was taller than his photos suggested and the darkness of his hair made Cora want to touch it.

‘Alright,’ he said, and handed over his passport.

‘Welcome to Aer Lingus, Andrew. Seat 27C, departure gate B – enjoy your flight.’

Andrew slouched away with that slow, wide gait favoured by young men. Personally Cora liked a man with good posture but, she reminded herself as much with relief as reprimand, this had nothing to do with her preferences. The check-in attendant picked up the phone and rang through to Aer Lingus Airbus A320.

‘Nancy? All set? Good. I’ve got one coming your way.’

TWO

LHR -> ENB 8.20 a.m.

Rita MacDonald was twenty-three and she’d had three relationships that you could probably classify as serious. The first was Adam, her teenage boyfriend. He wasn’t her first love though. Rita was pretty sure she was still waiting on that. But Adam was the first boy to meet her parents, the first boy to touch her boobs, and the first boy to make her appreciate the effect she could have on men. Then there was Aaron, her college boyfriend: first time she’d had real, official sex, first boy to write her a poem, and still her longest relationship to date. And finally Alex: first boy to say he loved her, first boy who was actually a man (twenty-nine), and first boy she’d flown across the country to break up with for a second time, because he refused to accept it until she did it in person.

Rita looked down at her boarding card, hoisted the leather bag up her arm and kept walking. When she got to Row 27, it was empty. She pulled the zip firmly closed and bundled the bag into the overhead compartment. She hadn’t needed much for one night in London. This trip had been about taking care of business. She sat in the window seat, pulled down the blind, and rolled her scarf into a pillow. Eight hours Alex had insisted they spend discussing the demise of a relationship that had barely stretched to six months – and half that time they’d been living in different cities. But if he felt better, and she felt less guilty, then it was worth a sleepless night and the cost of return flights. From now on though she’d be adding ‘can handle rejection’ to the list of criteria for people she dated, and she needed to rethink this unintentional preference for men whose names began with ‘A’.

There was a girl snoring in the window seat when Andrew Small got to Row 27. Jammy bird, he thought. The window seat was the only place he could ever sleep. Andrew took out his phone and composed a text message to his sister saying he’d made it on time. He was about to tell her his bad luck at landing an aisle seat but decided against it. That was the kind of thing they picked up on now.

‘Only an aisle seat? Aw, Andy, hadn’t they heard about your A-level results?’

They refused to call him Andrew. That was his new posh-o name. He’d always be Andy round their way. Which was fine, because he didn’t have to live round their way any more. He’d gotten out. His sisters resented that Andrew didn’t have kid hanging from every limb, and his dad resented that he didn’t have to spend his nights taxiing around drunks. They took him going to university as a personal insult. It scared them. But he wasn’t going to just make do: he was going to make something of himself.

‘Good morning, sir, welcome on board.’

Andrew looked up to see a blonde air hostess with a big smile and, he wasn’t being cheeky but, big knockers. ‘Alright,’ he said, trying not to go red. ‘Morning.’

‘Could you give the young lady a poke? Just need to get that blind up and we’ll have this plane in the air in a jiffy.’

Andrew wavered but the air hostess nodded her confirmation of the request. He leaned across the middle seat and shook the girl gently. She jolted awake and Andrew withdrew his arm. ‘Sorry.’

‘Morning, miss, welcome on board. If you could open your blind for take-off.’ The air hostess pointed towards the window, and the girl pushed it up. ‘Lovely. Now,’ she said, clapping her hands together, ‘can I get either of you a coffee? On the house. A thank-you for the assistance.’

‘Nice one,’ said Andrew, who had been getting into coffee since moving to Edinburgh. His flatmate had a percolator – not that he’d breathed a word of that back home.

‘Too good for tea now, is it? Do you have caviar with your coffee, Andy, or does that fuck with the aroma?’

‘Go on so,’ said the girl in the window seat, stifling a yawn. ‘I can never get back to sleep anyway,’ she said to Andrew as the air hostess left.

‘Sorry ’bout that.’

‘It’s not your fault. Planes are always a fucking nightmare to sleep on.’

‘Not even a lie,’ concurred Andy with a nod, who hadn’t been on a plane before he got into university and had never flown anywhere but Edinburgh.

Rita didn’t think of herself as shallow. Never. But then how was she to explain giving Alex the heave-ho? She’d told him they were just incompatible, in lots of ways: emotionally, socially—

‘Sexually?’

‘No! Of course not,’ she’d reassured him, and she supposed it was true. Rita had enjoyed sex with Alex. And if she hadn’t looked down that one time, she probably still would. But she had looked down, and she couldn’t ignore what she’d seen. That little bald patch right at his crown. It was such a turn-off that there had been no point in even trying any more, and she’d gently pushed his head away.

‘Just incompatible,’ she’d repeated last night, as she sat in his London flat listing all the vague reasons: emotionally, socially, geographically . . . But at no point did she complete the list. At no point did she tell him that the main way in which they were incompatible was follically. In that she had hair at the back of her head, and he did not.

The air hostess returned with coffee and Rita answered her questions about where she was from and what she did. The boy beside her answered too. He was from London but at uni in Edinburgh.

‘Pardon me,’ said a woman from the row in front. ‘I’d like a tea.’

‘We’re just serving this row at the moment. General in-flight service will begin when the flight is in the air and has levelled off.’ Then the blonde air hostess winked at Rita and her neighbour. ‘We’ve a soft spot round here for Row 27.’

When the air hostess left, Rita introduced herself.

The boy raised a hand in response. ‘Andrew.’

‘Fuck off.’

‘What?’

‘Sorry, no,’ she said. ‘Nothing.’

‘What? I don’t look like an Andrew? Is that it? Do not tell me I look more like an Andy.’

‘No, it’s not that. It’s just . . .’ Rita wasn’t sure how to say it without implying something unintended, but fuck it. She’d spent the whole of last night watching her words. ‘Every boyfriend I’ve ever had, their name has begun with “A”. I’m like a magnet for them.’

But Andrew didn’t even blink. ‘How many boyfriends is that?’

‘Three.’

‘Three? How old are you?’

‘Twenty-three. Why? Is three a lot? Are you saying I’m a slut?’ She wanted to add that she’d only slept with two of them and she’d never been in love with any of them, but she wasn’t going to explain herself. If he thought . . .

‘Fuck no. I’d never – no. I’m impressed,’ he said, and he did actually look it. ‘Three is good.’

You didn’t date girls round where Andrew was from. You slept with them and if you got them knocked up you might marry them, but there wasn’t much in between. His sisters had both gotten pregnant a year out of school. Rebecca got married, but Janine never said who the father was. ‘I’m not a grass,’ she’d screamed at their dad. ‘I’m not dobbing him in,’ and everyone just accepted this rationale.

At first Andrew felt guilty about going to university and spent far too much of his grant money flying home every weekend to sit around with his mates and mind his sisters’ kids, and slag off all the twats and tossers he’d met in Edinburgh. And that seemed to appease them a bit, because everyone just wanted Andrew to keep on being like them.

The day Andrew got his A-level results he’d gotten into a fight with his dad. ‘Big man now, Andy?’ his dad had said and Andy called him a jealous prick so his old man chucked a Pyrex dish at his head. That stuff had to happen, he supposed, two men in a small house. They didn’t fight as much now and this weekend had been more about silence and smart comments.

‘So that’s what you do all day, Andy, read books and have clever thoughts? Nice work if you can get it.’

‘Work? Andy wouldn’t know work if it kicked him in the nuts.’

And Andrew used to tell himself that it was their choice – that his sisters and his mates chose to stay around their way, and live in the shitty estate they’d grown up in and go to the same pub every weekend, or more often. But, deep down, he knew it wasn’t about choices; it was about the complete fucking lack of them. Which is why when he was offered some financial aid to study politics in Edinburgh, he hadn’t thought twice.

‘First in your family to go to university?’ asked Rita, who looked like she was in a band or wrote poems or something like that. ‘They must have been proud of you.’

‘They’d be prouder if I’d scammed a house on benefits. And I’m not even lying.’

‘But you managed to get a bursary, as an undergrad! Uni costs a bomb. You must be proper smart. If that was me, you wouldn’t be able to shut me up.’

‘It’s not really something I bring up at home.’

‘Well I think it’s amazing.’

‘Yeah?’ Andrew couldn’t help grinning. They weren’t at home now. They weren’t anywhere. They were in the air. ‘I think it’s fairly alright too.’

The phone rang.

‘Patch it through,’ said Nancy Moone, nestling the receiver between her chin and shoulder as she used her hands to stick a dry-packed toasted sandwich, ordered by a woman in Row 29, into the microwave.

The operations controller, who had a thing for Nancy and allowed her to receive mid-flight calls from Heathrow, disappeared from the line and was replaced by Cora.

‘How’s it going?’

‘Mixed bag, Cupid. At first I thought, “Total dud!” cause the girl was trying to get some shut-eye but then I swooped in with the classic—’

‘Coffee on the house?’

‘Worked a treat!’ Complimentary drinks was Nancy’s first port of call when it came to initiating conversation in Row 27. Free booze generally worked better, but it depended on the supervisor on board and not at eight o’clock in the morning. They were trying to keep a low profile after all. ‘They were chatting away.’

‘And then?’ Cora’s voice cracked down the line. ‘Are they still talking?’

‘Well then this nuisance of a stag party started acting up in Row 18, and I’ve been all distracted. And let me tell you, Row 18 is not where I want to be devoting my attentions. The bald fella from Game of Thrones is sitting up in Row 1, and I have yet to make it past the emergency exit.’

‘Come on, Nancy. I need more details!’

‘Hang on and I’ll check.’

Nancy let the phone dangle as she grabbed the ham and cheese from the microwave, leaving that door swinging too. She sailed down the aisle, past the hungry woman in 29E and stopped at Row 27. The boy was saying something about family and the girl was nodding enthusiastically.

‘Ham toastie?’

The pair stared up at her. Nancy liked how they were both tall. ‘No? Sorry then. Wrong passenger.’

She turned on her kitten heels, dropped the sandwich at Row 29 without so much as slowing her pace and caught the receiver on an upward swing.

‘Another success, Cupid.’

‘Really? I wasn’t sure she’d have the energy to engage . . .’

‘Well she did. And he was yakking away, all serious like.

Oh you can’t beat the young folk for the serious chats.’

A series of pings came from Row 18. Nancy straightened her back and rotated her shoulders.

‘Got to go, Cupid. The stag is back on the prowl.’

‘Guilt,’ said Andrew.

Rita nodded. ‘It’s the fucking worst.’

They’d discussed Edinburgh’s cliques and commuting, and by the time the plane had begun its descent Rita had told him why she’d come to London for less than twelve hours. Which brought them right to guilt. Not enough hair, too much distance, because she didn’t fucking feel like it; it didn’t matter the reason, she just wanted to break up. But guilt had made her pay ninety quid for return flights just so Alex could make her feel lousy in person.

‘I feel guilty even when I know I shouldn’t,’ she said. ‘I just hate feeling like I might be a bad person. And then I hate that I feel that way.’

‘I hear that, Rita,’ said Andrew, and she felt a shiver as her name made its debut on his lips. ‘I did my best to hate uni for the first two years because I thought liking it meant I was betraying everyone at home.’

‘And what happened?’ she asked.

‘I stopped going home so much.’

‘That’s rough.’

‘You’re not even lying.’

He was smart but not conceited and he had that confident thing going on, like he knew who he was and all that, and she loved his swagger. Real London swagger.

‘Guilt can be good too,’ she said. ‘It makes us do the right thing.’

‘Like what?’

‘Like when people pick up their dog shit. They do it so they won’t feel guilty.’

‘No they don’t! They do it because you’re looking. No way they pick it up when no one’s around. That’s public perception, not guilt. Like when I go to some public toilet and I wash my hands? That’s only ’cause some other bloke’s in there watching, judging me. I don’t do it if nobody else is in the place.’

‘Mate, that is rotten.’

‘What?’ Andrew was laughing too. ‘It’s only a piss!’

Rita scrunched up her face in disgust, but she didn’t really think it was rotten. The only thing Rita was thinking was that she was into him.

She asked what bands he liked and Andrew listed a few tunes he’d heard when he was out, but he didn’t really care. It was a real university question: ‘What music are you into?’ But it was just people trying to place you. No different from school. Though nobody in Edinburgh had ever asked what team he supported.

‘I mostly listen to talk radio,’ he said.

‘Like what?’

‘Like Radio 4.’ Another thing he would not be admitting to at home.

‘Wow,’ said Rita. ‘That’s cool.’

Andrew had learned most of what he knew about women from around the estate, and he’d never had any complaints. He was pretty confident when it came to sex. And he was a good kisser; that was something he’d prided himself on since he was twelve when the girls on his street said he was the only one of his mates who didn’t snog like a washing machine stuck on spin. But the problem with coming from a tribe where dating wasn’t part of the culture was that he didn’t have a fucking clue how to ask a girl out.

The stag party was awake and singing for its supper – or at least for a drink. One of them had spotted Nancy’s name-tag and they were having a great time.

‘I’ll do anything, for you, dear, anything . . .’ sang one.

‘Come on, Nancy!’ said another.

‘I’ll even fight your Bill.’

Having politely informed them it was 9 a.m. and so there would be no alcohol served on this flight, Nancy took her leave. She was always professional, but she was nobody’s fool. ‘Please, sir,’ they shouted after her. ‘Can I have some more!’

Nancy liked that she shared a name with the Oliver! heroine. She remembered going to see the musical at the Empire as a teenager and thinking the actress was proper gorgeous. Nancy usually told people she was named after Nancy Sykes. It was a lot more glamorous than being named after her Granny Moone. And this wasn’t the first time she’d had that song sung at her – I’ll do anything for you, dear, anything – only the last occasion had been at a nice holiday cottage in the Cotswolds and the crooner had been serenading her from where he stood, uncorking a bottle of rosé, at the end of the bed.

She walked past Cora’s couple just as the plane was near landing. Nancy loved it when Row 27 was a success. She reached the rear alcove and positioned herself slightly to the right, so she could monitor their exit. She tried to remember every detail so she could tell Cora.

You rarely meet someone who is proper different. Most of the people in your life are the same as you. This was what occurred to Rita as they landed at Edinburgh Airport. ’Cause yeah, we all think we’re weird or outcasts or whatever, but you’re still just going to the same gigs and the same pubs as all the other like-minded weirdos and outcasts. But when Andrew said he liked Drake – who was far too popular for Rita – she’d actually thought, this chap is amazing. And she fucking loved that hair.

The plane taxied to a stop and the blonde air hostess, the one who’d given them the free coffee, passed their row again. The intercom crackled: disarm doors and cross-check.

‘So are you going to ask me out then or what?’ she said, pretending to have difficulty with her seatbelt so she didn’t have to look at him.

‘Is it that you want me to?’

‘Well like, I got the impression you were mad into me,’ she said, trying to match his confidence.

‘Yeah,’ he said, grinning, and she wasn’t sure if it was a question or affirmation. They stood from their seats. ‘I was going to ask you’.

‘Just playing the long game, were you?’

‘Thought you might have reservations. What with my name being Andrew.’

‘Shit yeah, forgot about that. The dreaded A.’

‘Some of my mates call me by my last name, if that works better.’ He took his passport from his back pocket and handed it to her. She burst out laughing.

‘You’re alright, Andrew Small,’ she said, handing it back. ‘We’ll stick with your first name and see how we get on.’

They shuffled up the aisle, Rita admiring the width of Andrew’s shoulders and trying to keep a stupid grin from swallowing her entire face. They reached the exit at the rear of the plane to find the blonde air hostess standing there watching them, her perfectly white teeth wide between her perfectly painted lips. ‘I hope today’s flight got you both exactly where you wanted to go,’ she beamed.

And as Rita stepped out onto the ladder and into the bracing Edinburgh wind, she could have sworn she heard the air hostess whoop behind her.

THREE

Cora liked to think of matchmaking as a culmination of her better attributes: imagination, a sense of romance, an interest in people. Sure, it could be viewed as the pastime of a busybody, but she had yet to be accused of such. At least not to her face.

She made her first successful match as a teenager in her bedroom in the quiet London suburb of Kew. It was shortly after her parents separated. Sheila Hendricks (née O’Reilly) had come to London from Ireland after finishing school and gotten a position with the Heathrow branch of Aer Lingus. Her plan had been to transfer back home after a couple of years but then she met Cora’s Londoner father and England became her resident country, if never quite her home.

And having spent her adult life with a husband who ultimately repaid her geographical compromise with adultery, Sheila Hendricks was livid. She contemplated taking Maeve, Cora, and Cian back to Ireland, which was why she kept her married name; there was a rumour that, at Dublin Airport, single mothers were sent to work in Baggage Tracing in the basement. In the end, though, Sheila settled for throwing him out of their London home and insisting every room be given a makeover. There were weeks of furious redecoration, with her mother singing her own version of that Peggy Lee classic: ‘I’m gonna paint that man right outta my hair’.

Cora was given free rein to ‘express herself’ in her bedroom’s redecoration and the fifteen year old took this seriously. She painted the ceiling, every wall, the radiator, and the back of the door an appetising shade of purple. And the next morning, when the paint had dried, she sat on the floor in the middle of the room and cried. For the next however many years she would be sleeping inside a giant grape. But, when the furniture was reinstated and the woollen throws layered on the bed, the visual assault relented. In place of the old boy band posters were reproductions of paintings. Pride of place went to a framed replica of Sir John Everett Millais’s Ophelia – the same picture that has hung in every bedroom she has occupied since. This dark-haired woman lying heartbroken in a shallow ditch was as romantic an image as Cora had ever seen. It was how the fifteen year old expected, or hoped, love would one day feel. Sheila could never understand the attraction.

‘She’s just so tragic,’ Cora’s mother had said, standing at the doorway when the redecoration was complete. ‘Wouldn’t you rather a heroine on your wall? Someone who’s not a corpse? Joan of Arc maybe?’

‘Joan of Arc was burnt at the stake at twenty-one, Mum.’

‘Some other heroine, so. Your woman who kept the diary in the attic?’

The new bookcases had been embellished with a Shakespeare anthology, two Sylvia Plath collections, and James Joyce’s Dubliners. The new books could be distinguished by their smooth spines but she’d get around to cracking them eventually.

This decor – complemented by a self-imposed uniform of Che Guevara T-shirt and choker fashioned from black shoelace – represented the woman Cora was planning to become. She liked to picture herself at university, her briary hair calmed, her cosy bedsit filled with small canvases painted by herself, earnest boys calling over for tea in the hope she’d fall in love with them, and weekend protests and marches where everyone brimmed with passion. She wasn’t quite sure what causes she would advocate for, but she knew there were plenty out there. She’d be an idealist who was willing to engage; she’d be a romantic who cared.

On the day that Cora’s first great match was made, the teenager was sitting on her newly decorated bed, flicking through a photo album from the previous summer’s German language camp to which she was about to return. And this time Roisin, her best friend, would be coming too.

‘Did you know the name Ophelia didn’t exist before Shakespeare invented it,’ she said to Roisin, who was sitting on the floor, leafing through Cora’s modest but expanding CD collection. ‘He invented lots of words: “addiction”, “assassination”, “eyeball”.’ Cora had just discovered the Bard’s contributions to the English language and it was her new favourite fact. Roisin was less interested.

‘Do you have their first one?’ her friend asked, holding up The White Stripes CD. Roisin Kelly was the new girl at school that year. She’d moved to Kew from Dublin (Sheila had been very excited to hear of her daughter’s ‘Irish friend’) and her allure was amplified by the fact that Roisin owned a record player. Suddenly burning CDs didn’t seem so cool, and everyone had gone hunting in their parents’ attics. Roisin knew more about music than anyone at school. She identified as a Dylanologist, a neo-Curehead, and a Strokes groupie. She was a diehard muso.

‘First one? Yeah, got it ages ago,’ Cora breezed. ‘It’s probably downstairs.’ She made a mental note to find out what the White Stripes’s debut was and buy it at the next available opportunity. Building a music collection was impossible. The new stuff was always changing, the cool old stuff was endless, and Cora was working from a budget of Saturday night babysitting.

She slid down beside Roisin and placed the German college photo album on her knee. ‘What do you think of him? Just ignore the hair.’ Cora pointed to a smiling young man who wore a T-shirt signed by friends and who had added Sun-In to his spiked-up mane for the last day of camp.

‘Not really my type,’ said Roisin. It was the first Cora had heard of her best friend having a type.

They flicked through the rest of the album, Cora telling stories to accompany the pictures, until Roisin stopped on the penultimate page. ‘What about him?’

Standing two people over from Cora in a group shot was Roger Gorman. This was the boy whose group Cora would infiltrate at that summer’s German college for the sole purpose of setting him up with her friend. This was the boy Roisin would kiss at the diskothek on the last night after three agonising weeks in which she became convinced he did not know she existed. This was the boy Roisin would lose her virginity to the following summer, who she would date all the way through uni, and with whom she would thereafter move to Central London.

When Roisin and Roger split, Cora was devastated. She had hoped her first match would be her most successful, and she had the photo-album anecdote ready to go for the wedding speech. Still, Roisin’s single status meant she had been looking for a flatmate the previous year at the exact time Cora needed to relocate to the Finsbury Park area to be near her mother. Now Cora lived with Roisin above a twenty-four-hour sauna on the Seven Sisters Road. The exact activities of the all-night business were dubious but the women had never once had to turn on the heating. A third flatmate, Mary, had been there longer than either of them. Cora found her in equal parts fascinating and dull. Mary was doing Weight Watchers and had lost four stone. During that time, food had become her only interest. She made elaborate, low-fat meals for one in the evening and ate them in front of an endless stream of fat-shaming television programmes. A particular twist, Cora thought, was that by day Mary was a GP.

Roisin had been dating someone new for the past month or so – another Cora coupling. The two women had gone to The Dolphin one night over Christmas. Standing on the crowded dance floor, Roisin was despairing at how difficult it was to get talking to anyone in a London pub. ‘Where’s the shite talk? Where’s the drunken banter?’ Roisin shouted, her flat Dublin accent distinguishable above the music. ‘Look at them all, sticking to their own groups. Forget the class system, Cora, this is the great English divide right here.’

Without a word of response, Cora removed her left shoe and threw it into the middle of the dance floor. When the two women went to retrieve it, they found a bewildered man considering the boot that had smacked him square in the chest. Cora grabbed the flying footwear and walked off, leaving Roisin to explain. Since then, Cora had seen Prince Charming leaving her best friend’s bedroom most Saturday mornings. The ‘sole mate’ was one of Cora’s staple moves. She thought of it like catching the bouquet at a wedding, only with less commitment.

Cora was delighted for Roisin. She was glad something exciting was happening – and that it didn’t involve her. But when, in the early hours and half-asleep, she heard Prince Charming undoing the latch to let himself out, Cora’s past momentarily entered the present and the sound of the door closing jolted her awake with a churn of her stomach. And every time, even after rationalising that she was above a sauna in London and not in that four-storey walk-up in Berlin, she knew there would be no chance of going back to sleep. Cora knew it wasn’t him leaving her, saying nothing but making enough noise so she’d hear him go, but still Friedrich flooded her mind.

Whenever Cora visited her mother, enquiries were made about Roisin. Sheila described her daughter’s friend, in what was her highest compliment and generally reserved for fellow expatriates, as ‘salt of the earth’.

‘And is she seeing anyone?’ Sheila asked that Monday evening, after Cora had made them both a cup of tea and opened a packet of Sainsbury’s cookies. Her mother had been preening pot plants when Cora arrived and there was barely space on the desk for their mugs. Sheila had grown up in the countryside and had surrounded herself with greenery ever since. Cora pushed a sprawling fern to one side.

‘She is,’ said Cora, telling her mother the shoe saga for at least the third time. Sheila laughed and progressed to the inevitable question of her daughter’s own love life.

‘Nobody special to report.’ The stock reply.

‘You know Tom has a son about your age—’

But Cora cut her off. Tom was Sheila’s friend at the research facility. He was Irish too, and had come to Luton in the 1950s to work on the building sites. His Alzheimer’s was more advanced but Sheila still talked to him about Irish politics and sports.

‘Mother, I am fine. Honestly. I don’t need any help. I’m just taking a little break.’

‘I know, I know, and I think that’s very healthy. It is. But it’s been more than a year now since, your, what was his name. The man who never—’

‘Eight months.’

‘Eight months, right. I know you had a tough time, I know, sweetie pie, I do, but you know all men aren’t the same and we all have to get back on the, the—’ Sheila rotated her hands and Cora knew the word would never come.

‘I have to keep going?’

Her mother looked around. ‘Already?’

Sheila had always been the one Cora turned to when things went wrong. Maeve had been more independent and Cian was in his own world. But Cora and Sheila were close. When Cora was homesick that first year of German college, her mother posted her a mobile phone (summer school contraband!) and they talked under the covers at night. Sheila had been the sounding board when Cora was trying to decide what to study at university and it had been her mother Cora had phoned in floods of tears from Germany early one morning when the heartache and brain ache of second-guessing everything finally broke her. Sheila had ensured a standby seat for her daughter that same day and Cora was at home by teatime, crying into her mother’s lap, with half her belongings still in the Berlin apartment occupied by her ex-boyfriend but paid for by her.

But now her mother’s mind was failing and Cora was readying herself for the day when she no longer remembered all the things she had done for her daughter. You have to be ready, she admonished herself. It’s time to grow up. Cora feared telling her mother new information in case it pushed out the older, more important memories. Logically, she knew it didn’t really work this way – the doctors had explained the difference between short- and long-term memory – but still she wanted to pull a woolly hat down over her mother’s head to stop the dying brain cells from escaping through her ears.

Sheila’s memory started to wane a year ago, the usual stuff of lost keys and forgotten pin codes. One night Maeve called over for dinner, and her mother couldn’t remember how to extend the dining-room table she’d had since her wedding day. It was initially diagnosed as stress, then dementia, and eventually early onset Alzheimer’s. Sheila left her home for full-time care long before the doctors said it would be necessary. ‘I will not be a burden on my children,’ she repeated to each of them on the day she finalised the deeds to sell the house. But Sheila also had no intention of giving up on the rest of her life and, instead of going into a home, she signed up to live in a small, supervised facility where pan-European research was being conducted into the disease. Her vocabulary and short-term memory had worsened but she never forgot the names of her children or friends, and she asked just as many questions.