Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

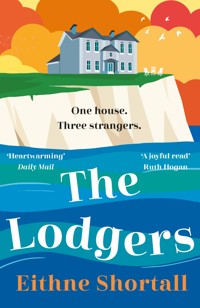

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

SHORTLISTED FOR POPULAR FICTION BOOK OF THE YEAR AT THE IRISH BOOK AWARDS 2023 'Heartwarming' Daily Mail 'A joyful read' Ruth Hogan One house, three strangers... Tessa Activist, 69 years young. Not ready to sell up her big seaside house, but she knows a little help around the place would do wonders. Conn Looking for a quiet place to heal after a family tragedy, this seaside escape would be the perfect haven if it weren't for... Chloe Arrives to drop off a package and leaves with a room. Her life is a bit of a mess, but this could be the start of a new chapter. She's ready for change. But is she ready for Conn? 'An ideal summer read ... by turns hilarious and heartbreaking' Irish Independent 'This moving, funny and charming novel is reminiscent of Marian Keyes' Louise O'Neill

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 577

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Also by Eithne Shortall

Love in Row 27

Grace After Henry

Three Little Truths

It Could Never Happen Here

First published in Great Britain in 2023 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2024 by Corvus

Copyright © Eithne Shortall, 2023

The moral right of Eithne Shortall to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 188 7

EBook ISBN: 978 1 83895 191 7

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.atlantic-books.co.uk

For my friend Dawn, who deserves a book

Blackpool, England

Muriel Fairway could have put it in the regular post.

She could have entrusted the Royal Mail and whatever its Irish counterpart was called with getting the item to Bea Pearson safely. But she hasn’t trusted the postal service since her twelfth birthday when her grandmother put a five-pound note into a card and personally handed it to her village postman. When it arrived through Muriel’s door three days later, the envelope had been torn at the top and there was no longer any money inside.

Fifty years on and Muriel still doesn’t put anything of value into a post box. She has a granddaughter of her own now and for her birthday she transfers money to her son’s bank account and posts a card to little Sadie (she just about trusts them with empty cards) to say her father now has fifty pounds belonging to her.

(Fifty pounds for a child’s birthday! How’s that for inflation?)

So Muriel has taken the parcel to Delivery Dash. She wasn’t going to take any chances, not with an item of such importance.

She has wrapped it securely, written the name in clear, bold letters – BEA PEARSON – and the address: Hope House, Nevin Way, Howth, County Dublin, Ireland. She has included a hundred-euro tip for the courier who gets it to where it needs to go in Dublin. She wouldn’t usually leave such a large tip, but it’s Bea’s money and Muriel is just following the young woman’s instructions.

Delivery Dash are reliable. The package will be in Dublin by Monday. Bea might not be there yet – Muriel isn’t sure when exactly she’s leaving Blackpool – but she’ll be home soon. The surprise party ‘of the century’ is in a few weeks – and who’d want to miss that?

It’s crazy how much Muriel knows about Bea. Before last Sunday, she’d never clapped eyes on her. One minute Muriel was walking her dog alone on Blackpool beach, the next she was finding out all about this Irish woman and her family. It’s funny how someone can come into your life like that, unexpectedly and all at once.

She knows about Bea’s brother Senan; about her deceased father Bernard; and about her mother Tessa, whose birthday is fast approaching. It’s an important one, a ‘roundie’ as Muriel’s husband calls the birthdays that mark the start of a new decade. And there’s going to be a celebration.

But perhaps the most intriguing detail about Bea is her home on the edge of Howth hill. Hope House. What a beautiful name. Muriel has never been to Dublin, but she has been given a clear picture of this place; rose bushes and oak trees that lend privacy to the vast property, cast-iron gates, and of course the breathtaking, unobstructed view of the expansive, glistening Irish Sea. It is the same sea that laps the coast of Blackpool, but Muriel believes it is even more beautiful on the other side.

Muriel loves family celebrations. After all those months of not being able to see each other, never mind celebrate anything (unless you were the prime minister, of course; then different rules applied), she is delighted when anyone gets to hug and dance and fete their loved ones. All the better if those joyous hugs are a bolt out of the blue.

Muriel signs the docket and hands it over to the Delivery Dash receptionist. Oh how she hopes this little package will be the cherry on the cake of the young woman’s homecoming.

It’s not her biggest hope though.

Her biggest hope is that Bea’s family can forgive her – and that Tessa’s surprise party goes off without any drama.

TESSA

THE SAME DAYHowth, Ireland

I’m not sure how it happened, but there’s an estate agent standing in my hallway unspooling a measuring tape while I hold the other end.

He has already done a walkthrough of the ‘property’ (aka my beloved home of forty-two years), jotting down the number of rooms (twelve; seventeen if you include the second-floor and basement scullery, which have been shut off for forty-one of those forty-two years) and condition of everything from the floorboards (original; oak; excellent) to the fireplaces (original; cast iron; not in tip-top form, but all functioning). He says he could ‘flip’ the house in a fortnight and that it would ‘do the three’.

My son Senan and grandson Otis, who are currently yielding a second measuring tape in the opposite direction, gasp at this.

‘What does that mean? Do the three?’ I ask, as the estate agent tugs the tape, and by extension me, towards the centre of the hall.

‘It means I can get you three million.’

‘For this house?’ I exclaim, almost letting go of my end.

‘At least.’ He peers down at the tape and writes the number in his gold-edged ledger. ‘What have you chaps got for the width?’

Otis squints at the implement in his hand. ‘Fifteen foot.’

‘But it doesn’t even have central heating! Who’s paying three million to have to put on their long johns every time they need the loo in winter?’

The man shrugs. ‘Everything’s a USP.’

‘A what?’ Another tug, and I just about get my stick moving in time. We’re measuring the depth of the fireplace now.

‘A unique selling point,’ he says, snapping the implement into its holder. I let out an involuntary yelp as it flies from my fingers.

‘Frozen pipes are a unique selling point?’

‘We are operating in a seller’s market, Mrs Doherty. There’s nothing that can’t be reframed as character.’

‘It’s true, Gran,’ says Otis. ‘My geography teacher is renting a shed in Raheny for €2,000 a month. It doesn’t have central heating either – just the family’s tumble dryer, which produces a bit of heat if you open it straight after a cycle.’

‘People are renting out garden sheds? As homes?’ I am aware of the desperate state of the housing market – I have attended several rallies demanding adequate housing for all – but it seems there are always new depths to plumb.

‘There’s a market for cosier, more affordable properties, and it’s a nice side earner for the owner. We have a few on our books,’ says the agent. ‘I actually noticed the little building you have out the back.’

‘What little…’ I frown. ‘The fuel store?’

He raises an eyebrow. ‘Or is it a bijou studio?’

‘It’s definitely a fuel store.’

Another shrug. ‘Like I say, potential is in the eye of the seller.’

I park this scurrilousness momentarily. ‘But three million?’ I repeat. ‘That’s…who has that kind of money? There’s been a leak in the attic for nearly a year now, and the plaster at the back is crumbling. If this house is worth three million, how can I afford to live in it?’

‘The joy of inherited properties,’ the agent retorts, putting his various notepads and tapes into a monogrammed briefcase. ‘Look, Mrs Doherty, my advice would be not to look a gift horse in the mouth. Accept your good fortune, sit back and think of what you’re going to do with all that money. You could buy one of those nice new apartments down by the harbour – no stairs, no draughts, bridge tables in the foyer – and you’d still have more than two million left.’

The man reaches into his breast pocket and produces two business cards.

I take one, but only so I know who I’m reporting when I contact the Residential Tenancies Board.

‘Would you be taking the furniture with you?’ he asks, rubbing a hand along the carved wood of a sideboard that once belonged to my late husband Bernard’s parents, and probably grandparents before that. ‘I could get you another hundred K for the contents.’

‘I won’t be taking any furniture because I won’t be going anywhere.’

Senan sighs loudly, but I ignore it. A valuation was all I agreed to, after persistent badgering. The idea that I’d leave this house is ridiculous.

‘Mrs Doherty,’ says the estate agent, flashing me his flashiest smile. ‘We see this a lot. People get attached to homes and they don’t want to leave, no matter how impractical they might now be for them. And this is a particularly lovely home. I understand. Who wouldn’t want to live here? All these rooms, all this space. But just think about how happy you’ll be making some young family. You’ll be giving them a place to live; you’ll be making all their dreams come true.’

I know what he’s doing. He’s trying to guilt me into a sale by appealing to my sense of civic duty, even though he’s only interested in the sweet two per cent commission that would go with selling a house for three million. (Three! Million!) This man is part of the problem, but he’s relying on me wanting to be part of the solution.

More annoying than being manipulated is that it’s almost working. The state of housing in this country is a disgrace. I don’t have a lot of money – despite what this recent valuation might suggest – but I have a standing order donation to the Simon Community, and I raised housing with every candidate who called to my door ahead of the last elections. I even think there’s something to the suggestion that older people consider downsizing.

But not me and not this house. What was Senan thinking, having the man come here?

‘Goodbye now,’ I say, thrusting my stick forward as I move towards the man. It’s an aluminium pole, like a crutch but with a curved neck at the top and, at the bottom, it spreads into four feet, each with a rubber soul for grip. It is an offensive pain in my backside, but it will be gone soon enough.

Senan, who can probably sense I’m about to clout the chap, takes the other business card and sees the estate agent to the door.

‘If you really were keen to stay on, I could look at making it part of the contract for any potential buyers. Maybe retain the fuel store,’ the agent calls after him. He slides on a pair of ludicrous wraparound cycling sunglasses as he heads down the steps, over the gravel and towards his car. ‘Give me a call, Mrs Doherty. It would be an honour to make you a very wealthy woman.’

When the door is closed again, and we hear the tyres rolling out of the driveway, Senan turns and smiles. ‘Three million, Mam? Can you believe it?’

‘I’m not selling. No way, no how.’ I hobble over to the sideboard and start sorting through my handbag.

‘Mam, you’re not even considering it.’

‘You’re right,’ I agree. ‘I said you could have the house valued, but I never said I’d sell. And I certainly wouldn’t let that man do it. I couldn’t live with myself if I knew someone as morally bankrupt as that was making money from my house. Whatever about forcing people to live in garden sheds, did you hear what he said about bridge? He comes into my house, uninvited—’

‘I invited him, after you okayed it.’

‘Uninvited,’ I continue, ‘and then he insults me?’

‘How did he insult you?’

‘By assuming I play bridge.’

‘You do play bridge!’

‘I play bridge ironically, Senan, as you well know. But that’s not the point. He doesn’t know that. He thought, “Oh, she has a stick, she must be old, she must need to go and live in some clandestine old folks home and spend the rest of her decrepit life playing bridge”. Well I’m not old, Senan. I’m in my sixties. Just like Demi Moore.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘You heard me.’

Senan sighs.

‘It’s a fact that this house is big and difficult to get around,’ he says in a tone that suggests I’m the one trying his patience.

‘Do you think that snake oil salesman would be telling Hollywood legend Demi Moore to sell her house, which is probably bigger and therefore more difficult to get around than mine? Would he suggest she go play bridge until death comes for her? No, he would not.’

Senan throws out his arms. ‘I give up.’

‘And Demi Moore wears glasses,’ I continue. ‘Meanwhile, I only really need mine for watching TV. She hasn’t made a decent film in twenty years and I’m still doing some of my best work, even if I’m not paid for it. I go on marches. I have an active social life. Up until that stupid fall, I played tennis more days than not. I still teach twice a week. And speaking of, I have a class in half an hour, so I need to get going.’

‘Gran is the same age as Demi Moore?’

‘Yes, Otis. Yes, I am.’

‘No, she’s not! No you’re not, Mam. You’re sixty-nine. You’re almost seventy. I don’t know as much about Hollywood legendDemi Moore as you suddenly do, but I imagine she’s sixty. Sixty-one, tops.’

I sniff at this. I’ve no interest in semantics. But Otis grins at me. He introduced me to the magic of IMDB last month and knows I’ve been addicted ever since.

‘That doesn’t make you the same age, and it also has nothing to do with anything,’ says Senan, who it seems is not as done as he said he was. ‘This is what your grandmother does, Otis. She distracts, she flummoxes. She’s a champion arguer. She did it for decades; arguing for housing, more resources – and her clients were lucky to have her because she’s very good at it, but this is different. Mam, you’re not a social worker any more. And I’m not going to let you talk rings around me.’

‘I’ve no idea what you’re talking about, darling,’ I say, rooting about in my bag for my keys. ‘Otis, would you be a pet, and get me the box of supplies I left in the library? They’re on the desk.’

My grandson gives me a salute and heads off.

‘Mam. Please. Don’t make me feel like some awful son who’s trying to turf you out of your home. I would never have suggested it if it wasn’t for your fall.’

‘My fall,’ I guffaw. What did I do in my former life to be cursed with such dramatic children?

‘But now,’ he soldiers on, ‘this house is completely unsuitable for you to be living in alone. The lack of central heating is only for starters. But on that, you’re not able to carry in wood and briquettes any more and you weren’t going to be able to do it indefinitely anyway. The dining room is damp. There are stairs everywhere. The kitchen is miles from the sitting room which is miles from the bedroom. There’s no toilet downstairs.’

‘Wasn’t it good enough for you and Bea to grow up in?’

‘That was years ago. It’s just you here now and needs change.’

‘I might be the only one living here, but this house doesn’t just belong to me. It’s yours and your sister’s too,’ I contend. ‘And you’re talking about selling it without even consulting her?’

‘I’m not making this about her,’ he says flatly, and my heart sinks. Is it my fault he’s still so angry at his only sibling?

‘All right then. What about your father? Hmm? This is the building where he took his last breaths, where I cared for him, where I raised a family with him. How could you sell all that history? If you truly believe there’s a suitable price for memories, then I failed in raising you.’

‘Memories don’t live in buildings; they live in our heads. We take them with us wherever we go,’ he says, parroting what sounds suspiciously like something his wife Audrey would say.

‘You used to make slides on all those stairs. Do you remember?’

‘A six-year-old sliding down the stairs is a lot different from a seventy-year-old having to climb them a dozen times a day.’

‘I’m sixty-nine!’

‘For another six weeks!’ Senan sighs again. ‘We’re going around in circles here. I know you’re not old, Mam, but with the stick, you need help. What if you fall again?’

‘Firstly, the stick is temporary. It’ll be gone soon. Secondly, I tripped over some shoes on the landing. Next time I need to go to the toilet during the night I will turn on the light. Lesson learned. It won’t happen again.’

‘You nearly died!’

‘Oh come on. I didn’t even really break anything. A little fracture to my hip, that’s it.’

‘You were lying there for hours. If Audrey hadn’t found you, you would have died of hypothermia.’

I roll my eyes, probably a tad too forcefully, but I never know how to react when he brings this up.

Senan thinks the reason relations between myself and his wife have been worse than usual is because Audrey found me sprawled across the landing wearing nothing but a pair of ancient grey underpants. And I, who am as comfortable with my body now as I was when I protested naked outside Dublin city’s fur shop several decades ago, want him to go on thinking that that’s all it is.

‘I’m just repeating what the doctor said,’ says Senan.

I put my handbag down on the chair that once sat beside his father’s sickbed – and indeed deathbed – and look my son squarely in the eyes. ‘I can’t leave this house. So you need to stop suggesting it.’

I expect him to shrink under my gaze, but he just looks sad. He feels sorry for me, his mother. He sees me as a lonely woman clinging to a house of memories. It’s splashed all over his face, and I can barely take it.

Otis reappears in the hall with a box of coloured paper, card, scissors, crêpe paper and string.

‘Perfect, love, thank you,’ I say, turning my back on my son to face my grandson. ‘You can carry it out to the car for me in a minute.’

But Senan isn’t finished. ‘What about a carer?’

We’ve been through this already. It’s worse than selling the house. Well, maybe not worse; but definitely more insulting. ‘A carer. Jesus Christ,’ I mutter. ‘I’m sixty-nine. Not ninety-nine. I’m probably still young enough to get a job as a carer.’

‘I know you’re more comfortable helping people than being helped, but—’

‘You think I need someone to give me a sponge bath and wipe my derrière?’

‘You need someone to help around the house. To bring in firewood and clean a bit, to carry the boxes that are too heavy or awkward for you now.’ He looks meaningfully at the class supplies in my grandson’s arms.

‘You could rent out a room?’ suggests Otis.

I laugh. ‘A housemate?’

‘I dunno. You could think of them as a tenant – a lodger or whatever.’

I ruffle my grandson’s hair, though the reach up does cause a twinge in my side. I’m five foot ten but he’s even taller. And so skinny. He turned sixteen over the summer and took a serious stretch. I don’t mention it because I think I offended my daughter-in-law last time, but, honestly, where’s the harm in adding a few more potatoes to his dinner plate?

‘I’m a tad old to be bumping into a stranger outside the bathroom, don’t you think?’ I say.

I throw my arm around my son, then. He really does look worried. ‘I’m fine, I promise. I can do most things myself. And for the odd jobs, don’t I have you and Otis and your lovely wife just down the road?’

‘But we’re not always at home.’

‘You usually are,’ I say, gently, not wanting to directly point out that I have a more active social life than my son these days. ‘You didn’t go away once this summer.’

He gives me a look like he’s going to disagree somehow, but then shakes it from his head. ‘Me and Audrey work,’ he says instead. ‘Otis has school, and now that we’re into the new school year, I’m going to be putting in long hours there too.’

I consider mentioning that he can always get here when it suits him – like taking himself and Otis out of school early when he knew the Bijou Henchman was coming – but I bite my tongue.

Senan is principal of the local community school and he’s a good man, just like his father. Bea, I’m afraid, takes after me; wilful and passionate and not interested in ever being wrong. I’m very proud of the work my son does and how he’s done in his career. I should tell him that more. I make a mental note to do so, soon, after my class. But right now it really is approaching 4.30 p.m. ‘I need to get going. Otis, will you take the box out?’

I make for the door, my grandson walking ahead of me, my son behind.

‘I can’t help thinking what would have happened if Audrey hadn’t called that morning,’ says Senan. The man is relentless. ‘She nearly didn’t, you know. She was going to visit her sister, only her sister had a vomiting bug so she knocked into you instead. I just…’ He shakes his head.

He’s always been empathetic, even when the concern is unnecessary. I’m his mother. I should be the one worrying.

And, actually, he is pale.

‘Are you getting enough sleep, darling?’

Now that we’re out in the afternoon sun, I can see clearly that he is not. No denying the dark crescents under those eyes. I will pick up camomile tea for him on the way home.

‘What would have happened if Audrey hadn’t called? Who would have found you? What state would you have been in?’

I squeeze his hand and give him a kiss on the cheek. I feel confident then that his wife didn’t tell him everything about that morning. ‘But you always do call. So it’s fine.’

Senan sighs. He appears to be out of arguments, finally. But just in case, I move quickly. I point my keys at the old Skoda so Otis can open the back seat and slide in my teaching supplies. Then I position myself on the top step. I’m a dab hand at descending these with the stick now. I pause at the halfway point and look straight ahead, out over the sea. An instant sense of calm descends. It really is a glorious day – excellent weather for doing some good.

‘Anything else, Gran?’ asks Otis.

‘That’s it. I’ll see you in the morning. We’re low on wood, so you might chop a bit then if you have time?’

‘Mam, Otis can’t—’

But Otis throws his dad a look. Quite right. This is between my grandson and me. He calls most days before school, and I never have him late. Besides, tomorrow is Saturday.

‘No problem, Gran,’ he says, opening the driver’s door for me. ‘See you in the morning.’

I kiss him on the cheek. ‘Thank you, my love. I’ll rustle up some pancakes in return.’

Someone needs to put fat on his bones.

The North Dublin Community Project is a programme of free classes, workshops, counselling groups and training opportunities available to anyone, from anywhere, who needs them. It’s a ten-minute drive from my house when there’s no traffic, which today there isn’t. I pull up in front of the former parish hall and grab the box of supplies from the back of the car.

Senan is wrong; I can carry my own materials. It just takes a little longer.

I’ve been coming here for almost ten years. I started out as an attendee, but I’ve always gotten more out of helping than being helped. My son was right about that bit. This term I’m signed up to teach two of my most popular courses. On Tuesday mornings, it’s Beginners’ Gardening. And today, as with every Friday: Radical Activism.

‘Sorry I’m late,’ I call, dropping the box onto the laminate table at the top of the room. Some years – usually after a general election or an increase in local parking fees – Radical Activism is in such demand that we have to use the main hall. This year I only have five sign-ups, so we’re in one of the smaller spaces off to the side.

‘I’ve been writing letters, Mrs Doherty,’ barks Malachy who, as always, is seated at the desk right in front of mine.

Malachy is a large man; tall and stocky with limited neck and a tightly shaved head that turns myriad shades of red whenever he gets worked up – which is all the time. He is a dedicated student and the only one still wearing the battered name tag I gave out on the first day of class.

Malachy was directed to the Project via a scheme for the long-term unemployed. He wanted to upskill, but when the labour market continued to elude him, he decided to throw himself fully into the community centre. When he’s not attending one of the thirteen courses in which he is currently enrolled (a Project record) he volunteers on the reception desk.

Now he is riffling through a stack of folded paper in front of him. ‘I haven’t posted any of these yet because I wanted to see what you think,’ he says, in his usual intense and clipped speaking manner. It’s like he’s only allowed so many breaths per day, and he’s rationing them. ‘I took on board what you said about not including threats of physical violence. You’re right; it distracts from the issue. I kept them short and to the point. I think they’re good now, Mrs Doherty. I think they’re fucking excellent, to be entirely honest with you.’

‘You big lick!’ calls Reggie, who is sitting on top of one of the tables at the back, still in his school uniform. Reggie is the youngest participant. He gets out of school one period early so he can make it to the Project on time.

He likes to remind everyone that this sanctioned truancy is the only reason he’s here.

He’s actually here because his parents thought it would be good to channel his disillusionment into something more constructive and less incriminating than spraying ‘Reggie woz ’ere’ on every wall within a two-mile radius of their home. Especially when he’s the only ‘Reggie’ for at least a ten-mile radius.

Malachy is too absorbed to register the teenager’s taunts. ‘I know you’re not keen on cursing, Mrs Doherty,’ he says, shaking out one of the folded pages, ‘but you’re always saying how important it is to channel our passion – and I think these letters show my passion. I wrote the same letter to every local politician and I stuck to my point, just like you said. I’ll read you one.’ He nods furiously to himself.

‘Let me just get set up first, Malachy, and I’ll…’ But he’s already off.

‘Dear Mr Foley. My name is Malachy Foster and I am a resident of your electoral constituency…’

He looks up. This is the starting template I provided last week. I give a firm two-handed thumbs up.

‘I am writing to you today in relation to the removal of the public bin at the junction of Seafield Terrace and Sutton Drive…’ Another glance up.

I nod encouragingly.

‘I personally believe this decision to be a fucking disgrace.’

‘Ah. I’m not sure…’

‘It is also my personal opinion that you had better put that bin back. Or else. Yours sincerely, Malachy Foster, 11 Seafield Terrace.’

My friend Maura, who has a few vigilante tendencies herself, breaks into a round of applause. Reggie, meanwhile, has fallen off his table in a fit of laughter. ‘A fucking disgrace!’ he howls.

Again, the jeers wash over Malachy, who is staring at me with such intensity that his left eye starts to twitch.

The other two attendees have just arrived. Susan is a forty-something mother of four young boys who only joined us last week and has yet to reveal much else about herself, and Trevor is a widowed retiree on the hunt for romance. He had his sights on Maura, but although he’s a decent man he’s also an awful know-it-all, and Maura had no interest in being mansplained to in the bedroom. ‘I’ll just about put up with it at the garage,’ she reasoned. ‘But what expertise I lack under the bonnet, I make up for under the sheets.’

‘What do you think, Mrs Doherty?’ asks Malachy now. ‘Whack a stamp on it, yeah?’

‘Mmm.’ I pick up the letter from his desk. ‘It might be a tad… Yes, I think so…’ I pretend to have to reread the five sentences, but actually I’m wondering if the reason we discourage schoolchildren from writing in red pen is because it makes everything read that bit more sinister. ‘A tad aggressive still, I think.’

‘Where’s the aggression? Where?’ asks Malachy, sounding aggressive.

He can’t help it, the poor lad. He’s a lovely man, actually very gentle – he attends my gardening class too where he has proven to be something of a flower whisperer – it’s just how his passion manifests. I’ve encouraged him to grow out the skinhead and to keep his sleeves rolled down over the meat cleaver tattoo, but it’s the innate aggression that’s keeping him from getting a job. He was so close with the hardware shop last month, but then he told them he’d fucking kill someone to work there – which is just Malachy for ‘I’m excited for this opportunity’ – and, well, there was no second-round interview after that.

‘We can’t threaten people, Malachy.’

‘More’s the pity,’ says Maura.

‘There’s no threat,’ retorts Malachy, his head pinking. ‘I took out the whole bit about setting a rottweiler on him – like you advised. Dano doesn’t have many going at the minute anyway.’ Malachy’s friend Dano runs a dog obedience school, though I’m not sure how good he is, since he’s always offering canine brutes to his pals for the purposes of intimidation. ‘The dog was the threat. And that’s all gone.’

‘Yes, but you left in the “Or else”.’

Malachy’s pink head progresses to fuchsia. ‘Could mean anything.’

‘That’s true,’ agrees Maura. ‘Mr Foley doesn’t know about Malachy’s friend’s rottweiler. It could mean, “Put back the bin, or else I’ll be disappointed”.’

‘Yeah,’ says Malachy, clicking his fingers in Maura’s direction. ‘Maybe I’m saying put back the bin or else I’ll write you another strongly worded letter.’

‘Well, that might work—’

‘Ya scaldy sleeveen.’

Susan flinches. She’s the nervy type and if you don’t know Malachy well enough to know he’s a lovable puppy under it all, his way with words can have too much bite.

‘Okay. Let’s come back to this,’ I say. ‘But it’s definitely an improvement, Malachy. The lack of nooses in the margins alone makes it so much better.’

Malachy pulls the chair in, sitting straighter, delighted with himself.

Maura leans forward and gives him a pat on the back.

‘Last week we made a start on letter-writing. Today we’re going to discuss the power of a good banner and of collective protest.’

‘Nothing like a march to make you feel alive,’ chimes in Trevor, a veteran demonstrator. He may originally have signed up to this class to pursue Maura, but he has come to enjoy the ample opportunities to detail his protesting knowledge.

‘I’ve never been to a protest,’ says Susan with reverent awe. ‘Have you gone to many?’

‘Don’t get the old man started,’ groans Reggie, who likes to wind up Trevor almost as much as Malachy.

‘Hundreds.’

Reggie throws his head back before flopping it onto his desk with a thud.

‘I won’t go through them all,’ says Trevor, pointedly. ‘But I’m a founding member of Grandparents for Trans Rights, so we go on a fair few outings. We actually store the banners in my greenhouse. I’d been to hundreds of protests before that too. I find them good for the soul.’

‘Agreed,’ I say. ‘Protesting is about the personal as much as the collective. That’s what a lot of people don’t understand. If you’re angry, like really hopelessly angry, there’s a short window before the fire in your belly turns to a dead weight that you’re forced to carry around like some stodgy cake you can’t digest for the rest of your life. But if you can get that anger out in time and channel it into something productive, it might just be the thing that saves you. The aim is not to become bitter; to take your anger and turn it into a force for good.’ I beam at the group. ‘We might go on one this year, if we can find a cause we all feel strongly about.’

Susan looks both excited and scared by the prospect.

‘I’m not much of a marcher myself,’ says Maura, who is only in this class to chat to me. ‘I prefer direct action. But we went on one as part of the course last year, and you should have seen Tessa. Some young one handed her a megaphone while she sorted out her placards and next thing you know, Tessa is leading the troops.’

‘That was a lovely demonstration,’ I agree. ‘Reminded me of the old days, only without having to chain myself to anything.’

‘You used to chain yourself to stuff?’ says Reggie, incredulously. ‘Like what?’

‘Oh, whatever was going. Railings usually, but sometimes lamp posts, other protestors, an officer of the law once or twice.’

‘An officer of the… As in, a garda?’

‘Yes, Reggie,’ I say, enjoying the shock on the teenager’s face. The way he’s looking at me now: that’s the person I am – not some old woman hobbling about on a stick. ‘Sometimes you have to disrupt to get people’s attention.’ Malachy’s eyes light up at this so I row back. ‘But that’s a last resort. First, we ask for things politely. We make posters and we get walking. Now,’ I say, pulling coloured card from my box of supplies. ‘Let’s make those posters!’

Everyone gets to work. Trevor constructs a banner to add to his trans rights collection, while Malachy spends forty minutes doing elaborate mind map brainstorming before settling on ‘We Want Bins’. Reggie threatens to make a ‘Remove All Bins’ poster but switches to ‘Graffiti is Art’ when Malachy’s head goes so red it looks like he might pass out. Susan can’t think of anything, so she offers to do a second trans rights one, which suits Trevor because now he has someone to whom he can give instructions. Maura opts to make lots of mini signs to leave on the cars of the people who keep parking on the double yellow lines outside her house.

‘Move your car or get keyed,’ I read, picking up one.

‘Malachy’s suggestion,’ says Maura, cheerfully. ‘Good, isn’t it?’ When she’s finished turning the tail of the ‘y’ into a zig-zagged scrape, she puts down her magic marker. ‘How goes Operation Downsize? Senan sold the house from under you yet?’

I sigh. It really is depressing that at just sixty-nine he thinks I can no longer live in my own home. ‘He is worried about me,’ I say, ‘which would be irritating if it wasn’t so well-intentioned. You’d swear I’d ended up in a full-body plaster cast the way he goes on.’

Maura picks up the marker again and starts slowly drawing a cartoon car in the corner of one of her signs.

‘What?’

‘Nothing,’ she says, bending her head closer to the card.

‘Maura Gilbert. Since when do you hold your tongue?’

She puts down the marker. ‘I know it’s only your hip that is the problem…’

‘Exactly. One little hip.’

‘… but it does mean you can’t live independently.’

‘I do live independently!’

‘You live on your own. But you couldn’t live without Senan and Audrey and Otis calling in every day to fetch fuel and help with the cleaning and carry certain things.’

‘None of that takes them more than a few minutes, and I more than pay it back by cooking for them or giving Otis lifts.’

‘I’m just saying your life is different now, and so is theirs.’

‘How is their life different?’

‘They have to call in every day.’

‘They always called in.’

She raises an eyebrow. ‘Every day?’

‘Most days.’

‘And what if they’re not around? What happened when they were in France this summer?’

‘Well now, that’s where you’re wrong,’ I say, triumphantly. ‘They didn’t go this year. So it wasn’t an issue.’

‘I thought they went to France every August.’

‘Yes, but not this year. Something about Audrey’s work. She had a lot on.’

‘So this was the first year they stayed at home? And it was also the first time you couldn’t be left alone?’ The raised eyebrow is joined by a tilted chin. ‘What a coincidence.’

Before I can argue, Reggie is beside me, slipping his poster onto the desk between myself and Maura. ‘There,’ he mumbles. ‘Can I go now?’

‘Reggie!’ I exclaim, taking in the skilful lettering. He’s drawn the word ‘Graffiti’ like a mural. ‘This is exquisite. Look at that detail – the brickwork, the depth. It’s a work of art. Your talents were wasted on your neighbours’ walls.’

‘It’s whatever,’ says the teenager. He gives the poster another side glance. ‘I’ll probably just throw it in the bin.’

‘I’d bring it home if I were you. It’s really excellent, Reggie.’

Malachy is out of his seat and peering over my shoulder. ‘That’s dead good that is,’ he says, forcefully. ‘You’ve got skills, mate. Meanwhile, I tried drawing a bin and it ended up looking like a post box.’ He glances back at his own poster, and I surreptitiously wipe his spittle from Reggie’s. ‘That’s just going to be confusing.’

‘Turn it into something else,’ says Reggie.

‘Like what?’

‘A ball of paper? A crumbled-up election leaflet or something, being thrown into a bin.’

‘That’s a deadly idea, but I couldn’t do that.’

Reggie sighs. ‘Come on,’ he says, dragging his poster from our table and heading for Malachy’s. ‘I’ll do it for you.’

‘I’ve never met an artist before,’ says Malachy, slapping him on the back.

Reggie stumbles, then shrugs him off, but there’s no denying the blush.

‘You know Otis made the basketball team this year?’ says Maura when they’re gone.

I laugh. ‘No he didn’t.’ My grandson has been obsessed with basketball since he was too small to hold one. He tries out every year but never makes it past the reserves. Between the recent growth spurt and a summer spent flinging the ball into the net at the side of my house, I had thought his time might finally have come. But if it had, I’d be first on his list of people to tell. Otis is my only grandchild and we’ve always been close.

‘He did. Jason told me.’ Jason is Maura’s grandson. He’s in the same year as Otis, and Reggie, and he’s a star of the basketball team. ‘One of the guys broke his arm jumping out of a tree, and Otis got called up.’

‘You must have it wrong. I’m telling you; Otis would have mentioned if he’d finally made the team.’

Maura gives me a look that says she’s so sure of her position, she doesn’t need to argue any more. I grit my teeth.

‘Reggie!’ I call.

The teenager looks up from where he’s hunched over Malachy’s poster.

‘Is Otis on the basketball team this year?’

‘Otis Pearson? How do you know Otis Pearson?’

One of the many upsides of having kept my own name is that Reggie has never made the link between myself and Otis or, more importantly, Senan. I want to give the teenager a safe space – I don’t want him to think I’ll be reporting back to the principal.

‘He’s a friend of my grandson’s,’ retorts Maura. ‘Now answer the question.’

‘No,’ says the teenager, returning to his drawing. ‘Otis is not on the team.’

I smile triumphantly at my friend, but before I can say ‘I told you so’, Reggie interrupts.

‘Like, he was offered a place. After Shane George downed a naggin of vodka and became convinced he was an eagle, there was a spot. But Otis turned it down.’

‘That doesn’t make sense,’ I say, mainly to myself. My summer was soundtracked by the basketball walloping the side of my kitchen wall.

‘Said he couldn’t commit to training in the mornings,’ says Reggie. ‘I don’t blame him. Going to school an hour early just to bounce a ball around? And on Saturday mornings too? Nah, you’re all right, Fellow Tall Nerds, I think I’ll stay in bed.’

Maura turns back to me with a look that says, ‘Now do you believe me?’, but my own expression must be as awful as I suddenly feel, because it softens.

‘He didn’t tell them he helps you in the mornings,’ she says, quietly. ‘He just said he had other commitments.’

But this only makes me feel worse.

How could I have missed the sacrifices my family was making? How could I not have questioned Senan and Audrey skipping their annual trip to France? How did I not realise I was monopolising my sweet grandson’s time?

‘Oh dear,’ I say, remembering the exchange before I left the house this afternoon.

Senan was trying to tell me not to ask for Otis’s help tomorrow morning. I didn’t even register it.

I’ve always been so stubborn, so instantly sure of my own position. I am a crusader in the best and worst sense. When I was working, I put my clients’ needs before those of my family. I promised myself I wouldn’t let them down again.

‘You’re right,’ I say. ‘I’ve become a burden on my family.’

‘I never said that!’ exclaims Maura.

‘Well, it’s true. I have. That bloody fall. This stupid stick!’ I grab the thing by its curved neck, as if to throttle it. ‘But I won’t be a burden any longer.’

‘What are you going to do?’

‘I’m going to live by my words. I’m going to take my anger and turn it into a force for good.’

Across the room, Reggie is giving his poster a furtive look of admiration, before rolling the thing up and quickly stuffing it into his bag. Malachy is proudly brandishing his sign – the bin now reimagined as a leaflet and a more experimental bin opening drawn at the bottom – while Trevor and Susan ‘ooh’ and ‘ah’ encouragingly.

If I can do my best for these people, then I can do my best for my son.

‘I’m going to take in a lodger,’ I declare, recalling what else Otis said this afternoon. I lift the stick and bring it down with as much force as four rubber soles can exude on a cheap linoleum floor.

‘Like, have a stranger live with you? In your house?’ says Maura.

‘Yes.’ I swallow down my qualms. It’s the least bad option. At least this way, there’s the potential to help someone. My house is huge – too huge, I’ve always said. I was never comfortable with its illusion of wealth, even if we could barely afford to maintain it most of the time. I can look at this as my chance to give purpose to its magnitude.

‘You sound like you mean it.’

‘I do,’ I reply, literally banging home my point.

‘See?’ she says, pointing to my stick. ‘It is good for some things.’

CHLOE

‘Chloe?’

‘Yes, hi. I’m here.’

‘Hello? Chloe?’

‘Yemi! Hi,’ I shout, louder this time, turning my head towards the passenger side dashboard, where my phone is wedged between a washbag and several balls of colourful wool. ‘Can you hear me?’

‘Just about. Where are you?’

‘I’m in the car. I’m driving. I have you on loudspeaker.’

‘So you’re okay, then?’ she asks.

In eighty metres, turn left.

I indicate and move to the next lane, which is riskier than it sounds because the farside mirror is obscured by the duvet and pillows that occupy the passenger seat. The back seat is filled with a large haversack, several boxes of books and a couple of plastic bags stuffed with clothes and more bright wool. A lamp, a wash basket, a tangle of cords and several pairs of shoes partially block the rear window, but there is just enough space to see out. I’m fairly sure there’s nothing coming.

‘Chloe? Are you still there? Are you okay?’

‘Yes, I’m still here. And I’m fine, I’m just navigating a tricky…’ I make it into the lane without being rear-ended. ‘Phew. Okay. You have my attention. What’s up?’

Turn left.

‘Shoot!’ I nearly miss the turn, but just about spot it in time.

‘Where are you?’

‘I’m on a job,’ I reply. ‘Just picked up a package for delivery.’

‘So you’re okay then? Everything is okay?’

‘Yes, everything is okay. Why do you keep asking?’ Was I supposed to take that turn too? Since my mobile doesn’t have GPS, Delivery Dash provide me with a Satnav. It’s a relic from their storeroom – possibly the original Satnav prototype – and it is often several instructions behind.

‘Your mam phoned me,’ says Yemi.

‘What?’

I’m in the middle of changing gears and the car almost cuts out. I go to pick up speed again but there’s a ball of wool rolling around at the pedals.

‘Yemi, I’m so sorry,’ I say, reaching down and flinging the orange fabric into the back. ‘I can’t believe she did that. I’m mortified. How did she get your number?’

‘She said you gave it to her when you came on my hen.’

It’s easy to remember because Yemi’s hen party is the only night I spent away from home in the past two years. I only went because Mrs Sweetman from next door insisted upon it. She said she’d check in on Mam regularly.

‘Oh god, Yemi,’ I say, head turned towards the phone. ‘I really am sorry. I never thought she’d ring you.’

‘Don’t be silly. It’s fine. As long as you’re fine. Are you? Fine? She said you’re not answering her calls.’

‘I haven’t had a chance,’ I lie. There are already eighteen missed calls and a dozen texts that I can’t bring myself to open.

‘Did you guys have a fight?’

‘No.’

‘Because you never fight with your mam.’

‘Yes, well, it’s hard to fight with someone with stage three cancer.’

‘Especially if you’re you,’ agrees Yemi.

I am not known for my combative nature, it’s true, but I am also not the total pushover Yemi believes me to be. Just last week I returned fruit to the supermarket after opening the punnet to find two plums covered in mould.

‘She said she woke up from a nap looking for you but all she found was a note.’

My stomach twists. I bite down the guilt.

‘Which really doesn’t sound like you,’ adds Yemi.

At the next roundabout, take the second exit.

‘What happened?’

Maybe we should have fought. Would that have made leaving easier?

‘I don’t really want to talk about it,’ I reply eventually. ‘Not yet. I just need to get through this job. I’m sorry, Yemi. I know you’re trying to help.’

‘Well, if you want to talk, I’m here. And if you don’t want to talk, I’m also here.’

I’m so lucky to have Yemi. Truly. It’s not easy being friends with a carer. I say no to things far more often than yes, and I frequently cancel plans at the last minute. Even if I do make it out, I rarely have anything interesting to say. My only news is related to the state of my mother’s health. And that’s never good.

‘Chloe? Are you crying?’

‘No.’

‘Oh my god, you are crying. Where are you? I’ll come and meet you right now.’

Yemi thinks I’m not a crier because she never sees me do it. But actually, I am. I cried so much as a baby that my dad left. He couldn’t take any more wailing, which is why my tears give Mam PTSD. They remind her of being abandoned. So by nature, I’m a crier. But by nurture, I’m stoic. I’ve learned to keep my blubbing for when I’m entirely alone. Not when I’m about to make a delivery, in the middle of the day, on the phone to Yemi.

But then all the rules are out the window today. I’ve been swinging between crying and giving myself ‘first day of the rest of my life’ pep-talks since 9.30 a.m.

‘I’m fine,’ I insist. ‘You just had a baby. You are not going anywhere.’ I shake my head and force a smile until the happiness makes its way into my voice. ‘I’m fine.’

I catch my reflection in the rear-view mirror and the car jerks again. Blotchy face, manic grin, mascara splodged under my eyes, hair in desperate need of a wash, and car full of all my earthly possessions. Thank Christ my phone isn’t capable of video calls. I look like the Joker – if the Joker was suddenly homeless and a secret knitting enthusiast.

‘Your mam phoned me because she didn’t know where you were. You didn’t mention it in the note.’

My ‘note’ was all of five words long. So no, a forwarding address didn’t make the cut.

‘She’d no idea who else to phone. She thinks you moved out, Chloe. I told her that wasn’t the case, that you probably just needed to blow off some steam or whatever and you’d be back. I mean, you wouldn’t move out. You wouldn’t just leave her. Right?’

Take the second exit.

‘Why am I asking? Of course you wouldn’t. But it might be worth phoning to let her know. Or I can phone if you don’t want to speak to her just yet. I know she can be difficult, but, well, you know…’

As I veer off the roundabout, something topples from the backseat onto the floor and makes a loud clatter.

‘What was that?’

I glance in the mirror, careful to avoid the horror that is my face. ‘Record player. I hope it’s okay.’

‘You have your record player in the car?’

‘I have everything in the car.’

‘Shit, Chloe, seriously? You really did move out?’

‘It’s a break,’ I say. ‘I’m just taking a break.’

‘What…’ begins Yemi, before trying and failing again: ‘Why…’

I sympathise. If someone had told me this yesterday, I’d be equally lost for words.

‘Where are you going to go?’ she manages eventually.

Every change, wanted or not, is an opportunity. I read that recently. Given that I’ve just made the biggest change of my life without an iota of forward planning, I have got to believe that this will be one hell of an opportunity. ‘I’ll figure it out,’ I say, readopting the manic grin. Fake it till you make it.

‘Well, you can stay here. Peter and I would love to have you. And Akin.’

‘Oh, Akin! I didn’t even ask how little Akin was doing! Did the public health nurse call? Was everything okay?’

‘Yep, all good. He’s great. Looks more like his dad every day. But forget about the baby – he has somewhere to live. Come and stay with us. Please.’

‘Thank you, Yemi, but I am not about to arrive in on top of you three weeks after you’ve given birth.’ I glance at the Satnav. I must be nearly here now.

Turn right.

‘Where are you going to go?’ She doesn’t say it because she is a good friend, but she knows what my mother knows: If I’m not at home, and I’m not with Yemi, I don’t have anywhere else to go.

‘I’ll be fine. More than fine. This is a good thing,’ I say, telling her what I told myself this morning, as I drove around the same roundabout so many times that I started to feel seasick, tears streaming down my face, a mixed CD from over two years ago – the only CD I own – blaring Adele through my tinny car speakers. ‘I’m actually excited about the possibilities,’ I add. ‘This is going to be good for me. Great, even. Probably. Definitely!’

‘You have no idea, do you?’

‘Wow.’ I slow the car further, as I gawk out the window. ‘These houses…’

‘Don’t change the subject, Chloe.’

But I’m not. Nevin Way is a quiet off-road; bumpy tarmac, grass growing in clumps at the verge of an uneven narrow footpath, a few streetlamps and not much else. You might miss the houses altogether if not for the ornate plaques informing you that what dwells beyond these gates is not storage units or farmlands, but decadent homes. Homes so posh they don’t have numbers, only names. Some of the houses are obscured by shrubbery and tree-lined avenues, but the ones I can make out are all huge, unique, and breathtaking. This delivery comes with a pre-paid €100 tip. That sort of money is unheard of in the courier business, but it makes sense now. To the people who live here, it was like giving someone bus fare.

‘Chloe! Hello? I’m asking what your plan is.’

‘Hi, yes, sorry. It’ll be okay, Yemi. I have a plan.’

‘Which is?’

I take a deep breath and prepare to tell her what came to me so clearly that morning it could only be described as a vision. I was off the roundabout – having finally found the strength to decide on an exit – and pulled over in a hard shoulder, still sobbing, still lamenting my sorry excuse for a life. When suddenly it hit me; the last time I was truly happy. The greatest loss of my life. Which was also the greatest love of my life.

Another deep breath, then: ‘I’m going to get Paul back.’

When she says nothing for several seconds, I congratulate myself on the dramatic delivery. Only it turns out the silence is one of confusion. ‘Who?’ she finally responds.

‘Paul! Paul Murtagh! The love of my life?’

‘Oh, Paul,’ she says. ‘Paul, yes. I remember Paul.’

How could anyone forget? Paul was so gentle and handsome and smart. He had the cutest way of straightening his glasses when he got nervous or authoritative. And he loved me. My god, how he loved me.

‘I thought I had to let him go, but I was wrong. I made the wrong choice. And I’m going to get him back,’ I say, rotating my shoulders like I’m already preparing for the battle.

In 200 metres your destination will be on the left.

‘If you’re happy, I’m happy, Chloe. But I meant where are you going to live?’

‘Oh. I don’t know about that bit yet.’ I squint, the still-strong September sun at my back as I read the names on the plaques. Hallow House, Binn Eadair Beag, The Orchard all dotted along the street at generous intervals. No sign of Hope House yet. ‘I’ll probably just rent somewhere.’

Static comes through the phone and I reach over to adjust it before recognising the sound as laughter.

‘Yes, because it’s that easy. It took Peter and me weeks to find this place, and we can just about afford it – on two full-time salaries! I’m not being funny but, like, I know what those courier shifts pay. Do you know what rent costs? Have you ever paid to live somewhere?’

She knows I haven’t. Paul and I were supposed to rent a flat, we’d paid the deposit, but then Mam came home with a Hodgkin’s Lymphoma diagnosis and all talk of how many cushions a bed needed and whether eggs should be kept in a press or the fridge was forgotten.

‘I read the news,’ I reply defensively. ‘And I got a big tip for this job. And now that I don’t have the same responsibilities at home, I can take on more deliveries. If worst comes to worst, I can stay in a hotel for a few nights.’

‘A hotel? In Dublin? That tip would want to be astronomical.’

‘Well, a hostel then.’

‘A hostel? Chloe, are you trying to give me a heart attack? Just come stay with us, okay? You’re not ready for the big bad world.’

‘I’m not a child, Yemi. I’m the same age as you.’ You’d be surprised how often I have to remind her of this.

‘I know. But your experience of the world is more…’

‘Yes?’ But at the same time that I ask this, I turn my head to the right and give a genuine, wind-knocked-from-my-sails wheeze.

‘Oh, now. Oh, wow,’ I mutter.

Yemi is still searching for a tactful way to tell me that the most interesting thing about my life is how boring it is, but my attention is right here. Out this window. Focused on this view.

This is why all the homes are located on the left-hand side. If you were to build on the right, you would be blocking this; the most magnificent sea view I have ever seen in real life. Or in any virtual form for that matter.

You have arrived at your destination. Your destination ison the left.

The clouds part and the sun shines straight down onto a patch of the Irish Sea, like some sort of celestial beam calling souls up to Heaven.

Your destination is on the left.

‘Your experience is more limited. That’s all,’ says Yemi eventually. ‘I worry about you, out there by yourself…’

‘Wow,’ I whisper again, barely listening. The unspeakable upset of this morning fades, falling from my shoulders and gliding straight out into the vast body of water. My problems seem so insignificant when faced with the unending expanse of the calm, glistening sea. I am humbled by the water, I am calmed by it, I am—

‘Oh no.’

I am off the road.

‘Oh no, no, no.’

I have come to the end of Nevin Way and unwittingly mounted a low kerb and I am now on a modest green, wheels rolling over soft grass and I am travelling slowly but with increasing speed towards a hedgerow. There is a gap in the shrubbery and all I can see through it is blue. At first I take this to be sky but, as the distance between me and it continues to narrow, I recognise it as sea.

At the next opportunity, rejoin the road.

‘No, no, no, no, no!’

‘I’m sorry if I offended you, Chloe, I’m just trying to say…’

At the next opportunity…

I slam on the brake and push my body back in the seat. Nothing appears to change but then, after another awful few seconds, the car slows. It comes to a stop.

I close my eyes and pull up the handbrake.

Phew.