Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Corvus

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

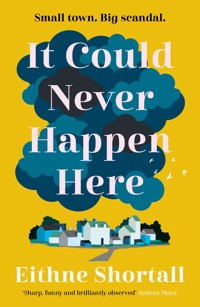

'Brings twist after delicious twist. I love this book.' Jo Spain ______________________________ Small town. Huge scandal. Beverley Franklin will do whatever it takes to protect her local school's reputation. So when a scandal involving her own daughter threatens to derail the annual school musical's appearance on national television, Beverley goes into overdrive. But in her efforts to protect her daughter and keep the musical on track, she misses what's really going, both in her own house and in the insular Glass Lake community - with dramatic consequences. Glass Lake primary school's reputation is about to be shattered... 'Eithne Shortall mixes humour and tragedy with a deftness reminiscent of Marian Keyes' Irish Times

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 493

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Published in hardback in Great Britain in 2022 by Corvus, an imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd.

Copyright © Eithne Shortall, 2022

The moral right of Eithne Shortall to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Hardback ISBN: 978 1 83895 184 9

Trade paperback ISBN: 978 1 83895 185 6

E-book ISBN: 978 1 83895 186 3

Printed in Great Britain

Corvus

An imprint of Atlantic Books Ltd

Ormond House

26–27 Boswell Street

London

WC1N 3JZ

www.corvus-books.co.uk

Also by Eithne Shortall

Love in Row 27

Grace After Henry

Three Little Truths

For my dad, Billy Shortall, who made me coffee while I wrote and always served in a Seamus Heaney ‘Inspiration’ mug…

In case you thought I didn’t notice.

1

••••••

ABERSTOWN GARDA STATION

The parents and staff filed into the police station. Pristine coats hung from their confident shoulders, and huddles quickly began to form. A few threw glances in Garda Joey Delaney’s direction and he did his best to look authoritative from his position behind the reception desk. He lifted his blink-and-you’d-miss-it backside from the swivel chair, placed both hands on his belt and yanked it up, ready for action.

‘Delaney, get in here!’

The young guard swung around to see his superior, Sergeant James Whelan, already disappearing back into his office.

He gave the belt one further hoist and quick-stepped it in after him.

‘The first batch seem to all be here now, sir.’

Whelan lowered himself into the chair with a groan. The sergeant was forty-six – exactly twice Joey’s age – but he moved like a man of far greater years. Garda Corrigan pointed this out to him once and Whelan snapped that being tethered to useless eejits such as him was slowing him down.

‘Did you mark their names off the list?’

Joey had expected the parents to approach the desk and formally check in, but most of them had ignored him entirely. ‘I’ll go around now and do a roll-call.’

‘You do that. I’ll just finish up in here, and then we’ll get started.’ The sergeant lifted the remains of what looked like a chicken sandwich from his desk and took a bite.

‘Do you think they’ll know anything, sir?’

‘If there’s anything to know, that lot will be in the loop.’ The sergeant nodded towards the door, to the staff and parents of Glass Lake Primary beyond. ‘They pride themselves on it.’

Glass Lake was a sought-after school located one town over in Cooney. Curtains were due to go up on its annual musical tonight and even Joey had a ticket. He wouldn’t normally be too keen on watching a bunch of twelve-year-olds perform The Wizard of Oz, but the other officers insisted the school’s shows were always unmissable. ‘West End quality at West Cork prices,’ was how Corrigan had put it. Not that it mattered now. There would be no musical tonight, or any other night this week. Obviously.

Joey nodded, hands on belt, as he marched out of the sergeant’s office and over to the desk where he had left the clipboard of witness names. He was determined not to be another useless eejit slowing the sergeant down.

He cast an eye over the list and then over the busy waiting area. Yesterday evening, this lot had been up at Glass Lake, getting the auditorium ready. Now, they were in Aberstown Garda Station preparing to give their two cents on the body that had been pulled from the River Gorm while they were busy painting the Yellow Brick Road and putting finishing touches to Munchkin costumes.

They were still waiting on the initial post-mortem results and Joey knew the most likely cause of death was accidental. Eleven months he had been a qualified guard stationed at Aberstown and, until yesterday, there hadn’t been a reason to switch on the siren of the station’s sole patrol car.

This wasn’t a part of the world where robberies happened, never mind murders.

Still, thought Joey, as he hitched up his trousers and strode over to the whispering masses, there was no harm in keeping an open mind.

Extracts from witness statements, as recorded by Garda Joey Delaney

Mairead Griffin, school secretary

It was pandemonium yesterday evening. It’s been pandemonium ever since the parents learned this year’s musical was going to be on television. They’ve been turning up in their dual roles of legal guardians and Hollywood agents, and God help us all if their child isn’t standing right where the cameras are going to be. If a single one of them noticed anyone was missing – if they noticed anything other than how high their child’s name was listed in the programme - then let me know and I’ll keel over right here and die of shock.

Susan Mitchem, parent

I fully support postponing the musical – a mark of respect, absolutely – but I had a casting agent coming to see my son and I’ve had no clarity on when to reschedule the train tickets for. I’m in serious danger of losing my money. The whole thing is tragic, one hundred per cent, but as the old maxim goes: the show must go on.

Mrs Walsh, teacher

It’s just so sad, isn’t it? Imagine how cold it must be in the water, especially at this time of year. A tragic, tragic accident – and this town has had enough of those. My thoughts are with the family. You hear about these things on the news, but you don’t really think about it, not properly, not until it happens to one of your own.

2

••••••

FIFTEEN DAYS EARLIER

The front door opened, and Christine Maguire leapt from the sitting room into the hallway, knitting needles and almost-completed teddy bear left languishing on the sofa.

She held her index finger to her lips and gestured up the stairs.

‘Well?’ she whispered. ‘Did you find him?’

Her husband removed the thick thermal gloves the kids had bought him for his birthday. ‘I’ve got four pieces of news,’ he said. ‘Three pieces of good news and one piece of bad news.’

‘Jesus, Conor. Did you find the cat or not?’

Christine was the only member of the family who hadn’t wanted a cat. Hers was the one vote, out of the five of them, for a dog. (Brian wrote ‘porcupine’ on his piece of paper, but given the options were ‘dog’ or ‘cat’, her son’s ballot had been registered as spoiled.) The animal had sensed Christine’s outlier position from day one and returned the disdain ten-fold. And yet here she was, unable to go to bed until she knew the damn creature was safe.

‘I found him,’ said her husband, undoing his jacket. ‘Porcupine is alive and well.’ (Such was Brian’s aggrievement at being excluded from the democratic process that they’d allowed the seven-year-old to choose the pet’s name.)

‘Thank God.’ Christine leaned back against the wall and glanced up the stairs. ‘Maybe now Maeve will go to sleep.’

‘They’re the first two pieces of good news.’

She watched him jostle with the coat rack. ‘What’s the third?’

‘He’s being very well cared for in Mrs Rodgers’ house.’

‘Mrs Rodgers, of course! Why didn’t we think of that?’

Rita Rodgers was an older lady who lived at the end of their street and spent a lot of time tending to her rose bushes – a real jewel in Cooney’s Tidy Towns crown. The local pets were known to stop by and keep her company while their owners were out. She’d lived a fascinating life – literally ran away with the circus – and she exuded a worldly calm. Christine often said they were lucky to have Mrs Rodgers on their street; she was a reminder to stop and smell the (prize-winning) roses.

‘Good old Mrs Rodgers, ay?’ she said. ‘We should drop her down a box of chocolates, to say thank you. I can pick something up tomorrow. I’ll go tell Maeve that all is well.’

Their middle child had added Porcupine’s disappearance to her ever-expanding list of things to lose sleep over. Other items included the teddy bear she was supposed to have finished knitting for school tomorrow (hence Christine currently committing late-night forgery) and a sudden, strong fear that she would not be involved in the Glass Lake musical.

Maeve didn’t want to act in the production, which was a pity; she was the only one of Christine’s children with the looks for stardom. (She wasn’t a bad mother for thinking that. Maeve was her prettiest child, but Caroline was the most intelligent, and Brian the most likeable. Everyone went home with a prize.) Maeve wanted to work on costumes, but some other girl was already signed up to do that. Christine didn’t see the problem. It was a school show staged by a bunch of pre-teens. Surely the attitude should be: the more the merrier.

‘Hang on,’ she said, as Conor continued to mess around with the coat rack. It did not take that long to hang up a jacket, even if you approached things with as much precision as her husband. ‘What’s the bad news?’

‘Hmm? Oh.’ Conor frowned at the woollen collar as he attached it to a hook. ‘She doesn’t want to give him back.’

‘What?’

‘Mrs Rodgers, yes. I was surprised too. But she was quite firm about it. I always thought she was dithery, but I guess that was ageism. She’s actually impressively sharp. She knows we’re gone from the house for at least seven hours every day and that Porcupine is left on his own. She did this bit where she opened the front door wide and told Porcupine that he was free to go. Go on now if you’re going, she said. And Porcupine looked up at her and meowed. Now I know he meows all the time, especially when he’s hungry or when it’s early and—’

‘Yes, Conor, I’m familiar with the cat’s meow.’

‘Right. But this was different. This meow sounded like a word.’

‘Excuse me?’

‘A human word, I mean.’

Christine squinted at her husband, who was supposed to be the brains of the family. He raised his hands in a wait-for-it gesture.

She waited.

‘And it sounded … like, “No”.’

Christine smacked her lips.

Conor nodded.

‘What?’

‘I know,’ he said, still nodding. ‘Crazy. Porcupine did not budge. I took off my hat, so he’d recognise me, but nothing. He just stood at her feet, loyal as you like. I have to say, it was very impressive.’

‘What did you do?’

‘What could I do? She was very nice about it. She explained that we were very busy – which is true, you said the same thing when we first talked about getting a cat – and probably didn’t have a lot of time. But she has plenty of time and lots of space. She’s an animal person, and she’d really cherish the company. I could almost hear her rattling around in the place, the poor woman. You know her husband died?’

‘Yes, forty years ago, Conor! And they were separated. She left the man for a tightrope walker!’

‘If we were separated and you died, I’d still be sad.’

‘What? Conor, no! She stole our cat!’

Now it was her husband’s turn to put his finger to his lips and gesture towards the stairs. ‘Porcupine looked happy. I know it’s only been a couple of days, but he looked fatter.’

‘That cat couldn’t get any fatter.’

‘I don’t know why you’re so annoyed, Christine. You never liked him anyway.’

‘She stole our cat! She cannot just steal our cat!’ Christine caught her voice before it escalated to a full-on roar. That woman, their nice, old, butter-wouldn’t-melt neighbour, had abducted their pet. How many times had Mrs Rodgers called out ‘Busy today?’ as Christine hurried past her house? When Christine called back ‘Up to my eyes, Mrs Rodgers’, she’d assumed she was making polite chitchat, not fashioning the noose for her own hanging. ‘I should have known,’ she raged. ‘I should have known she wasn’t the person she said she was. The Tidy Towns committee asked everyone on the street to leave some grass and dandelions in their gardens, but she just eviscerated it all. Animal person, my foot! She doesn’t give a damn about the bees!’

‘To be fair now, Christine, we’re not too worried about the bees ourselves. I just haven’t got around to fixing the lawnmower.’

‘And how, exactly, could Porcupine look happy? That animal has one expression and it is smug.’

‘Well,’ Conor conceded, ‘he looked sort of smugly happy.’

‘Doesn’t she already have a cat? A white and ginger thing?’

‘I have a memory of seeing her with a brown one,’ said Conor, ‘but maybe not. That was a while ago.’

To think how many times Christine had stopped to compliment Mrs Rodgers on her ‘organic’ roses, knowing full well the charlatan was using chemical fertilisers. The Maguires lived on the same street, they had the same soil, and they could barely grow grass. But Christine never said a word. And when Mrs Rodgers won the intercounty garden prize, she’d written an article about it – she’d even pushed to get a picture of the old bat and her performance-enhanced bushes on to the front page.

‘So, what? We leave him there? And then what? What are we going to tell the kids? What are you going to tell Maeve?’

‘We’ll just explain that Porcupine is an individual,’ said Conor. ‘He was a kitten but now he’s a cat and he’s decided to move out, like the three of them will one day …’

Christine threw her head back and hooted.

She prided herself on being able to see her children for who they were. In Maeve’s case, that was an anxious, conscientious little oddball. Dr Flynn had diagnosed her constant worries as ‘intrusive thoughts’ and said some children found comfort in prayer. But Conor was resolutely atheist – except when it came to ensuring their children got into Glass Lake Primary: then he was all for standing beside a baptismal fountain and shouting ‘Get behind me, Satan’ – so he bought her a set of worry dolls instead. Christine could have sworn their sewn-on smiles were already starting to droop.

Then, right on cue, their eleven-year-old daughter appeared at the top of the stairs.

‘Why aren’t you asleep, Maevey?’ Conor called up.

‘I was saying prayers for Porcupine. Did they work? Has he come home?’

‘I’ve found Porcupine,’ said Conor, ignoring the first portion of the question. ‘And he’s alive and well.’

Maeve gasped and started to run down the stairs.

‘No, hang on, hang on. He’s not here. He’s at Mrs Rodgers’ house.’

‘Why is he at Mrs Rodgers’ house?’ Maeve directed this question towards her mother but, with a swing of the head, Christine lobbed it on to Conor.

‘He’s, well …’ Conor looked to his wife, then down at their daughter, his lips curled into a smile that didn’t reach his eyes. That was his first mistake. Kids could spot a ‘bad news’ smile a mile away. ‘When we got Porcupine, he was a kitten. But now, now he’s all grown up. He’s graduated from kitten college. He’s passed his feline driving test. He’s an adult, he’s a cat ...’

Maeve’s face shifted involuntarily.

‘… and when people, and animals, grow up, they move out of home. When I was a child, I lived with your granny and grandad, but then I grew up and now I live here with you …’

There it was again, a spasm just under the left eye. Christine winced in sympathy. A twitch. Wonderful. Just what the girl needed.

‘… and when you grow up, you’ll move out of this house too.’

‘But I don’t want to move out.’

‘It won’t happen for a long time.’

‘I don’t want to move out,’ repeated Maeve, her voice creeping higher. ‘I want to stay here. Mom? Do I have to move out? What if a baddie broke in or the house went on fire and I didn’t know because I was asleep and there was nobody there to wake me or what if—’

‘This is way, way in the future, Maevey,’ explained Conor as the child’s breathing grew louder. ‘By then you’ll be big, and you’ll want to go. Caroline will move out first—’

‘Caroline’s moving out?’

Conor flinched. ‘No, she’s—’

‘Why is Caroline moving out?!’

‘I just meant because Caroline’s older, she’s fourteen and you’re only—’

‘Shush now, Maeve, breathe normally. It’s all right. Caroline’s not going anywhere,’ said Christine, deciding her daughter’s mental well-being should probably trump a learning opportunity for her husband. ‘None of you are. We’re all staying here, until we’re old and grey and roaming around the house with walking sticks. All right? Okay?’

‘And Porcupine is staying too? Until he’s old and grey?’

‘I’m not sure … Conor?’

‘Dad?’

‘He’s …’ Conor suddenly looked very tired. ‘Yes. Porcupine is staying too. He’s just having a sleepover at Mrs Rodgers’ house.’

‘A sleepover.’ Maeve rolled the word around, deciding whether to believe it.

‘Exactly. Like when you stayed at Amelia’s house for her birthday and slept in sleeping bags and ordered pizza. I’d say Porcupine will have pepperoni, what do you reckon?’

Maeve smiled. ‘He does like meat.’

‘He loves meat,’ said Conor, taking the reprieve and running with it. ‘I’d say he’ll ask them to bring a couple of portions of garlic sauce too, for dipping. Does that sound like Porcupine?’

‘Cats can’t dip, Dad.’

‘No,’ he agreed.

‘He’s having a sleepover?’

‘Yes.’

‘And he’ll be home tomorrow?’

‘Absolutely.’

‘That’s great news,’ Christine chimed in, parodying her husband’s enthusiasm. ‘I look forward to seeing him then. Now, Maeve, back to bed.’

She followed her daughter up the stairs and into her room, which had the same animal wallpaper and curtains as when she’d first moved into it. Maeve had always been young for her age. She had an innocence that even Brian, four years her junior, was starting to shed.

The bedroom’s centrepiece was a large noticeboard covered in drawings. Currently, it was dedicated to costume ideas for the Glass Lake musical and multiple, very similar pencil sketches of Porcupine. She’d done a good job of capturing his sly, soulless eyes. The noticeboard was always so singular in focus, and the artwork so concentrated, that it gave her daughter the air of an obsessive stalker. Maeve had got her single-mindedness (and her peculiarity) from her father. When Christine first met Conor – at a party in a squat in what felt like another lifetime – she couldn’t believe anyone grew up wanting to be a dentist. Yet by all accounts her husband’s childhood bedroom had been much like this, only his noticeboard had been a shrine to teeth.

‘Thank you for helping me with the teddy bear,’ said Maeve as she climbed into bed. She took a tissue from the nightstand, wiped her nose, and pushed it under her pyjamas’ sleeve.

‘No problem.’

‘And thank you for going to meet the Lakers tomorrow.’

Christine smiled tightly. ‘No problem.’

The Lakers were the mothers, mainly alumni, who ran Glass Lake Primary from the shadows. The most ridiculous thing about the Lakers was that this was also how they referred to themselves.

‘You can’t be late, okay? The Lakers are never late, so I don’t think that would go down well. If you’re going to be late, you probably just shouldn’t go at all.’

‘I won’t be late, Maeve.’

‘And I was thinking maybe you could wear some legging things and a puffed waistcoat, maybe with fur on the collar …’

‘Like the ones Amelia’s mom wears?’

‘Yeah, kind of like that.’

Amelia’s mom was Beverley Franklin, a prominent Laker and director of this year’s school musical. She used to work at a pharmaceutical company but now she sold jellies that were 70 per cent vegetables on Facebook and spent too much time on the sixth-class parents’ WhatsApp group.

‘I’m not sure I have one of those jackets,’ said Christine diplomatically. ‘But it’ll be fine, I promise you. I’m going to charm the pants off those other mothers, and I’m going to get you a position working on costumes.’

Maeve didn’t look wholly convinced. ‘You do know Amelia’s mom, don’t you?’

‘Yes, I told you,’ said Christine, tucking the duvet in around her daughter. ‘I was in her class at Glass Lake – just like how Amelia is in yours.’ I just don’t pin my entire identity on it, she added silently. ‘Me and Beverley go back years. Okay?’

Maeve gave a small nod.

‘That’s my girl.’

The Lakers organised annual golf outings and reunions (For a primary school!) and lucrative fundraisers. They had no say in the academics, thankfully – going on some of the stuff sent into the parents’ WhatsApp groups, there were a few anti-vaxxers in their midst – but they had a regrettable amount of input into extracurricular activities. They met at the Strand café on Cooney Pier every Thursday morning, and if you wanted your child to make the swim team or get a solo in the choir or to work on costumes for the annual sixth-class musical, you better believe you were pulling up a chair and ordering a flat white.

Conor couldn’t understand this because Conor was a blow-in – meaning he’d only been living in Cooney for sixteen years as opposed to being born, bred and, crucially, educated here.

‘It seems insane that you have to take a whole morning off work to meet some women in a coffee shop just so Maeve can maybe be involved in the school play,’ he said as they climbed into bed that night. ‘Surely the teachers decide who gets to work on it.’

‘It is insane. But that’s Glass Lake. The parents are far too involved; they were even when I went there. But if it eases Maeve’s mind, I can put up with them for an hour or two.’

‘And where will Derek think you are?’

Derek was her boss at the Southern Gazette. He’d been editor of a national tabloid in Dublin until a heart attack, and his wife, forced him into a slower pace of life.

‘I’ve told him I’m meeting a source.’

Derek regularly talked about tip-offs and whistle-blowers and sources. Christine, who specialised in hundredth birthdays and local council disputes, found it best to just play along.

‘Anyway,’ she said, ‘you’ve got your own morning to worry about.’

‘My Thursday’s looking pretty relaxed,’ said Conor, sleep making its way into his voice as he nuzzled into her. ‘Nothing but routine check-ups until a root canal at noon.’

‘I’m talking about the morning-morning, dear husband, and what exactly you’re going to say when Porcupine doesn’t turn up for breakfast.’

................

Maeve Maguire didn’t like getting out of bed in the middle of the night. The house was scarier and colder and sadder when the lights were off and everyone else was asleep. And she didn’t like leaving her worry dolls unguarded. She lined them up under her pillow every night, and without her head to hold them in place, she worried they’d get up and run away.

In the daylight, Maeve knew they were only dolls and that dolls couldn’t walk, let alone run. But at night, things were different. This was when the four tiny women in their bright dresses and dark pigtails would make a break for it. They would escape and tell everyone her secrets. She pictured them skipping along the streets of Cooney, avoiding the glow of the streetlamps and jumping over any deep cracks in the footpath (they were only teeny after all; shorter than Maeve’s middle finger) before they slipped into people’s letterboxes, under their front doors and through any windows left ajar. She imagined them hopping up the stairs of these homes, sliding under doors and scaling the beds of Cooney’s residents as they squeezed around pillows and climbed beside ears so they could whisper all the bad things that Maeve Maguire of Sixth Class, Glass Lake Primary, had done.

Maeve’s biggest worry was that the dolls would achieve all this in the time it took her to get downstairs, do what needed to be done, and return to bed again. If Santa Claus could get around the world in a night, one little coastal town wasn’t going to be much of an ask, especially when they could split it between four. If Maeve never knew they’d been gone, then she’d still go into school the next morning, where everyone would know her bad thoughts and bad deeds, and it would be too late to pretend to be sick.

She lifted her pillow and was comforted to see the dolls just as she’d left them. She looked away, then turned back extra quickly. They didn’t move. She returned the pillow and slowly swung her legs out of bed. She crept out of her room and closed the door behind her. She grabbed a towel from the landing and pushed it against the gap under the door. She pulled the used tissue from under her pyjamas sleeve and squeezed it into the keyhole. Just in case.

Then, quick as she was able, and without making a sound, she snuck downstairs and did what she had promised to do.

3

••••••

Beverley Franklin never wasted time. She did squats while brushing her teeth and jumping jacks when waiting for the kettle to boil. If suppliers placed her on hold, she put her phone on loudspeaker and cleaned a shelf of the fridge. She left floss beside her laptop and worked a thread of it around her mouth as she waited for the machine to load. And in the mornings, between shouting ‘Rise and shine’ and ‘Let’s go, let’s go’ at her two daughters, she did whatever household tasks could fit into the short window.

The first task this morning was to take delivery of the teddy bear. However, the taxi she’d ordered to collect the stuffed animal from Cooney Nursing Home had ignored either her precise timing instructions or the local speed limit and the driver was knocking on her door, package in hand, before she’d had a chance to deliver the first wake-up call.

‘Twenty-six eighty,’ said the driver, as she took the bag and removed the bear she’d commissioned several days ago. She’d read about the knitter in the Southern Gazette: an illustrious textiles career in Paris then London, where she made garments for the royal family. The article read like an obituary, but it had actually been to mark the woman’s hundredth birthday. The centenarian played hard to get at first – retirement this, arthritis that, partial blindness the other – but Beverley kept phoning the nursing home and upping the fee until she relented. And, credit where it was due, the woman had delivered. The bear was navy blue with button eyes, a large white belly and a right arm an inch longer than its left. It was perfect, but not too perfect – just as Beverley had requested. She carried the thing through the foyer up the main flight of stairs to Amelia’s bedroom and knocked on the door, ready to rouse her.

‘Rise and shine, ma chérie,’ she said, pushing the door open to reveal the pleasant surprise of her youngest daughter already up and dressed and sitting at her vanity table.

Amelia turned from the mirror. ‘He’s so cute!’ she exclaimed, arms stretched out towards the bear. ‘Thanks, Mum. I didn’t even know you could knit.’

‘If you have a problem, I have the solution. Now. Are you ready to wish your grandmother a happy birthday?’ A lifetime of grafting had taught Beverley that when making morning to-do lists you should start with the task you most want to put off. ‘I’ll stand by the window. The light is better.’

She crossed the room to the bay window and pulled her phone from the pocket of her next-season Moncler diamond quilted gilet. (Shona Martin’s mother was a buyer for Brown Thomas, and she’d gifted it to Beverley when she was announced as director of this year’s Glass Lake musical.) She scrolled to video.

‘Do you want to wish her a happy birthday, and I’ll record it?’

‘That’s all right, chérie. She’d much rather see your lovely face.’

Amelia, thankfully, understood nothing of difficult mother-daughter relationships.

The girl gave her ponytail a firm tug and stood poker straight by her pale pink wardrobe. Beverley nodded and Amelia flew into action.

‘Happy birthday, Granny, I love you so much!’ she gushed. ‘I can’t wait to see you again. Thank you for being the best grandmother in the world! You’re amazing!’ Most people’s eyes would be engulfed by a smile that wide, but Amelia’s exaggerated features could take it. ‘Happy birthday,’ she sang, then she blew three gorgeous kisses to the camera and it was all Beverley could do not to reach out to catch them.

‘Parfait!’ she enthused, pressing stop on the video. ‘Absolutely perfect. That could have come straight from the account of an A-list influencer.’

Amelia smiled modestly. She had more than 2,000 followers on Instagram – double that of any other child in her class. ‘Thanks, Mum.’

Amelia had inherited more from her mother than high cheekbones and excellent hair. She was driven and hard-working. She wanted to be an influencer and she had what it took to make it. That wasn’t Beverley being a deluded parent, either. She wasn’t like Lorna Farrell, who was convinced the school choirmaster had said Marnie was a ‘pre-Madonna’ and now believed her daughter was destined for world domination. Beverley actually had experience of the entertainment industry.

‘I promised my followers I’d post my everyday make-up routine,’ said Amelia, switching on the ring light they’d bought for her recent birthday. ‘It’s more authentic if I do it in the morning.’

‘Authenticity is very important,’ agreed Beverley, who had read a lot about social media strategies before launching Sneaky Sweets, the health food start-up she ran online. ‘Don’t forget to take off the make-up when you’re finished. Glass Lake rules. Ten minutes, then downstairs for breakfast. You don’t want me coming back in and ruining your shot.’

Although actually, wouldn’t it be kind of cute to feature some candid bloopers? Beverley had toyed with suggesting she take a cameo role in Amelia’s socials. Followers responded well to glimpses into family life. Amelia could post occasional clips from her acting days and then Beverley could talk about what a fun time it had been but how family was more important.

If only all this technology had been around when she was younger, her career could have been so different. Magazines and newspapers had been obsessed with Beverley – and what were they, if not the social media of their time? (Ella was forever telling her she was obsessed with things – herself, Amelia, cleanliness, Glass Lake – but this had been real obsession. There was a two-month period where she’d appeared in the Sunday Independent every single week.) More people had heard of Beverley Tandon (as she was then) than Pauline Quinn, the young temptress she’d played on Cork Life. Beverley remembered her agent telling her this like it was a bad thing: ‘You’re not Julia Roberts, Bev. You’re a soap actress.’ Now, though, self-promotion was an asset. She ran Sneaky Sweets almost entirely through Facebook and it was doing well. There were a lot of desperate parents frantically searching the internet for ways to feed their fussy eaters. But however good Beverley might be at selling jellies made from vegetables, she’d have been so much better at selling herself.

‘Mum!’ chided Amelia.

‘Nine minutes,’ she said, stepping back out on to the landing.

Phone still in hand, she opened the last recorded video. She wrote ‘Happy birthday’ and deleted it. Then she wrote ‘Happy birthday, Mam.’ ‘Happy birthday, Frances.’ ‘On your special day!’ ‘HB, Mama.’ ‘Peace and light x.’ The last one was definitely the most Her Mother. She deleted it too and just clicked send. The video was self-explanatory.

Mentally ticking the task from her list, she strode along the landing. This was usually when she delivered Ella’s wake-up call. However, last night she had politely asked her eighteen-year-old daughter if she had any plans for the weekend – she wasn’t even that interested; she was just waiting for the Duolingo update to load – and Ella had responded by asking why she was so obsessed with her. (If anyone was obsessed it was Ella; and she was obsessed with the word ‘obsessed’. Beverley should have said that last night. She always thought of retorts hours too late.)

She paused at the bottom of the stairs that led to the next floor. Ella’s first lecture was at 10 a.m. – Beverley had her university timetable linked to the Alexa family calendar, along with Malachy’s work schedule, Amelia’s after-school activities, and her own myriad appointments – and if she didn’t get up soon, she’d be late. But Beverley kept walking. If that was how she was going to speak to her mother, she could sing for a wake-up call.

Next up was the toilet bowl in the main first-floor bathroom. There were, as Malachy had so eloquently described it a few hours earlier, ‘stringy particles’ stuck to the edges. She ran the hot tap and pulled the bleach and a pair of rubber gloves from the box of cleaning supplies Greta kept in the bathroom cupboard.

Ella accused her of ‘Catholic guilt’ for cleaning before Greta came, and ‘white privilege’ for having a cleaner in the first place. Whatever about being white (everyone she knew was white!), the Catholic guilt accusation was untrue. Greta worked for all the Glass Lake mothers, and Beverley cleaned before she came for the same reason the Franklins did their banking in Cork City rather than Cooney and Beverley went all the way to Dublin to see her dermatologist. Because people talked. And she’d rather not give them anything interesting to discuss.

Pulling on the Marigolds, she grabbed the toilet brush firmly in both hands and applied brute force to the rim of the bowl until the debris came loose.

‘It looks like bits of food,’ her husband had said, as he stood at the foot of their bed at 5.30 that morning, stretching his glutes in preparation for his daily pre-dawn run. Malachy did not share Beverley’s inherent drive – he’d been born wealthy instead – but when it came to his appearance, he found the motivation. ‘I wouldn’t be surprised if Ella has an eating disorder.’

‘I doubt it,’ Beverley had replied, as he placed his palms flat against the wall that separated their room from the second guest bedroom. ‘It’s probably just hard water build-up. I’ll take a look.’ Then, because he still wasn’t appeased, she added: ‘You look well toned.’

Flattery always settled her husband.

She carried the toilet brush over to the sink now and rinsed it under the flowing tap. It was important people thought she’d never dream of cleaning her own toilet, but the actual act of it was nothing. Hard graft and an eye on the future. That was how she’d secured such an enviable life.

Tick, tick.

The final item on Thursday’s to-do list was admin. There were seventy-two unread WhatsApp messages. Being a Glass Lake mother was a full-time job and Beverley already had a full-time job, no matter what Ella thought. (It was hard to be a girl-boss role model for a daughter who dismissed your crusade to revolutionise the food industry as ‘refreshing your Facebook page’.) Beverley was sometimes tempted to let elements of school life slide, but there were parents and children counting on her, not to mention the reputation of Glass Lake itself. She skipped the Sixth-Class Parents group, the Wonderful Wizard of Oz group, the School Trip to Dublin group and opened the Lakers thread.

Lorna Farrell said, ‘Is it terrible that Thursday is my favourite day because I get to have a Strand café flapjack?’ Fiona Murphy said, ‘That’s how I feel about Friday – aka Wineday.’ Lorna Farrell sent two cry-laughing emojis. Claire Keating said, ‘Wineyay!’ and sent a gif of a monkey drinking a bottle of Merlot.

Beverley went to put the phone away – they were meeting in forty minutes, for Christ’s sake, no wonder she was the only one who ever seemed to get anything done – when a new message came through from Lorna.

‘Today’s meeting is going to be extra special – get ready for BIG news, ladies!! Isn’t that right @BeverleyFranklin?’ This was followed by a wink emoji, and then a cry-laughing emoji. Lorna ended all her messages like this, even when it made no sense.

The top of the screen alternated between telling her Claire was typing and Fiona was typing. ‘What’s the news??’ said one. ‘Spill spill!’ said the other.

Beverley’s grip tightened.

She was director of this year’s Glass Lake Primary musical. She was the one who’d lobbied the national broadcaster. Everything Beverley had done, from selecting the highly visual Wonderful Wizard of Oz to thinking big on set designs and casting the leads early, had been to catch the TV station’s attention. She’d sent in headshots of Amelia and Woody Whitehead. (If anything proved Beverley’s commitment, it was her willingness to cast a Whitehead. They were a scourge on Cooney, but even she couldn’t deny the youngest son had a face, and name, for stardom.) And it had worked. Lorna Lick-Arse Farrell was not going to steal her thunder.

Beverley composed herself and fired off a response–

‘BIG news, ladies. HUGE. I’ve a hectic morning on here, but I’ll do my best to get to the Strand early. Á bientôt.’

– then she locked her screen and slid the phone back into her pocket. She shoved the bleach and gloves behind the cistern – Greta would tidy them away – and hurried out on to the landing.

On Thursdays, Beverley had Amelia at school for 8.40, dropped Malachy’s shirts to the dry-cleaner’s when they opened at 8.50, and was over at the Strand café on the other side of Cooney for 8.55. She would hang back in the car until she saw a few other mothers go in. Just because she no longer worked in the city didn’t mean she had time to be sitting around waiting on people. This morning, though, she’d be in there first. Amelia could be a few minutes early and the shirts could wait.

She walked purposefully along the landing – let’s see who was obsessed with what when Ella was late for college! – and headed for her younger daughter’s bedroom.

Had she thought about it, she would have knocked. They’d talked about privacy last summer and agreed Amelia was entitled to some.

But she was in a hurry.

Her mind was full of Lorna Lick-Arse Farrell and how the Yellow Brick Road still looked bronze and the way Malachy had watched himself in the mirror that morning.

She was distracted.

She wasn’t thinking.

She turned the handle to her daughter’s room without any warning.

‘Chérie,’ she was saying before she was fully through the door, ‘we’ve to leave early so maybe you can do—’

Amelia looked away from her phone. She was standing near the window, holding the too-large device aloft in her too-small hand as she angled it towards her body. Her entirely naked body.

‘Mum!’

Her daughter – her beautiful, ambitious, twelve-year-old daughter – was wearing a full-face of make-up and not a stitch more.

Her skinny arms pushed against her sides, causing her barely-there boobs to move ever-so-slightly closer together and the skin at her sternum to dent. Beverley had never seen her do anything remotely like that with her mouth, her cheeks, her eyes. She barely recognised the expression as belonging to Amelia. The prominent hip bones and faint wisps of pubic hair came as delayed shocks, and the sticky, cherry-coloured gloss bleeding up on to the skin above her puffed out lips made Beverley’s stomach lurch. But it was the pleading look on her daughter’s face that would haunt her. It said ‘like me’ and ‘love me’ and ‘reassure me’ but also, and this was too much for Beverley because she was sure her daughter didn’t even know what it meant and didn’t want to imagine where she’d seen it, it said ‘fuck me’.

This pushed Beverley over the edge.

Shock, upset and fury reverberated around her body, rattling against her ribcage and up her trachea, before launching themselves into the pale pink room in a high-pitched guttural scream.

No amount of chalky blusher could stop the colour disappearing from Amelia’s face; a blackbird fled from the window ledge behind her; and a teenage boy awoke in a room upstairs where he’d been sleeping, all night, entirely unbeknownst to Beverley.

4

••••••

Arlo Whitehead’s dream always went the same way. He and Leo and Mike were playing on stage at a massive stadium that was Madison Square Garden but also Cooney Parish Hall. Arlo had never been to New York (he’d never been further than Lanzarote) but he’d watched Tom Petty live at Madison Square enough times to know the venue. Sometimes Neil Young was watching from the wings, and sometimes it was the guy who’d driven their school bus. Whoever it was, he was always totally impressed. It was all going well – until the last song. Even though Arlo could never hear anything in his dreams (he wished he could; the crowd were totally into whatever they were playing), he knew they were falling out of time. When he looked over at Leo, ready to shout at him to sort it out, he noticed his best friend no longer had arms. Leo was just looking down at the guitar hanging around his neck, screaming. Leo screamed and screamed at the instrument until his face started to melt away.

Arlo had googled ‘How to stop having the same dream’. The most common suggestion was to write down the details so he could interpret their meaning. But this was the only dream he ever had, and it didn’t take Freud to work it out.

So, when he was roused by an almighty roar, he wasn’t overly alarmed. He assumed it was Leo screaming about his missing limbs and was relieved to have woken before his friend’s face started to run down his body.

But then he remembered where he was, and that there was never noise in his dreams.

He pushed himself up in the still unfamiliar four-poster bed and looked over at Ella. She was also awake, and though she wasn’t screaming, there was a look of mild alarm on her perfect face. (Ella’s perfection was beside the point, but it was difficult not to register, no matter the circumstances.)

‘That’s my mum,’ she said, and suddenly he was completely alert.

‘Your mom?’ He scrambled further up, grabbing his T-shirt and navy jumper from the floor before climbing out of the bed. ‘What time is it?’ His foot caught slightly on the under sheet, which had come untucked. ‘Shit, Ella! I knew I shouldn’t have come over last night!’

Ella’s parents did not know about Arlo. Well, they knew about him, in the way that everyone in Cooney knew about him: as Charlie Whitehead’s son, a subject of suspicion, and the only teenager to have walked away from the Reilly’s Pass crash intact. But they didn’t know about him in the way that mattered: as Ella’s boyfriend, as the love of their daughter’s life.

‘Where are my trousers? Why didn’t the alarm go off?’ he said, lying on his front on the floor so he could see under the bed. The Franklins’ carpet had to be felt to be believed; it was softer than his own bed at home. ‘Maybe someone saw me sneaking in last night? There are so many streetlights around here. I don’t think there’s more than three in our whole estate. I knew it was too risky.’

‘Arlo, breathe,’ said Ella, climbing out of the bed. She had a red mark on her left cheek from how she’d slept and was wearing the E&A necklace he’d bought for her birthday and his favourite Dylan T-shirt. They had cover stories ready for where both items had come from, but Ella’s parents never asked. Her hair was dark blond and cropped. She’d cut it short to piss off her mother, which Arlo didn’t condone, but it was sexy. Although it was sexy when she’d had it long, too. Her eyes were pale blue and hypnotic, like an ocean. He’d written that into a song, but he hadn’t shown it to Ella yet. Lyrics without music were cheesy. And with Leo gone and Mike gone-gone, he’d be waiting a while for someone to put it to music.

His trousers were not under the bed.

‘Maybe your sister told her. Would Amelia do that?’

He was back on his feet and Ella was coming towards him. Already he felt happier. The mark on her cheek was a perfect circle. Half of him marvelled at how that was possible, and the other half thought, ‘Ah, but of course’. Everything about Ella Belle Franklin was perfect.

He’d never been in love before and it was amazing. Sometimes he’d be working away, thinking about nothing but expanding pipes or shelf brackets, and then he’d be overcome by a giddy, nervous feeling, as if it was Christmas Eve or the day of some amazing gig, but it was actually just because Ella existed and she wanted to spend that existence with him. Wasn’t that incredible? Love was better than all the songs said, even Leonard Cohen’s. He wouldn’t go as far as to say it was better than sex, but it was definitely equally good.

‘Amelia wouldn’t do that,’ she said, standing in front of him. ‘My mum doesn’t know.’ Ella was the only person he knew who said ‘Mum’. He’d thought only English people said that. But then the Franklins were very wealthy, which was almost the same as being English. ‘Not that I’d care if she did find out.’

‘I know, but I care. I need more time.’

A couple more months of working hard and word would get around (as you could rely on it to do in Cooney) that he was a pretty decent lad and not, in fact, ‘just like his father’. Then Arlo could look his future parents-in-law in the eye and tell them how wonderful their daughter was. The plan involved turning up early to every job, putting in long hours, doing good work and never saying anything rude no matter what was said to him. The plan did not involve getting caught in Ella’s bedroom with no trousers on.

‘Relax. There’s no way she knows. Bev is too wrapped up in her own life to notice.’ Ella also called her mother ‘Bev’. She did it to annoy her, even when she wasn’t there.

‘She was yelling about something.’

‘She probably spotted a blackhead in the bathroom mirror. Or maybe Amelia wasn’t wearing the exact Glass Lake regulation knee socks. Who knows why Bev does anything? But there’s no way she’s coming near this room. I told you, we’re fighting.’

Arlo tried not to come to Ella’s house too often – getting caught sneaking up the Franklins’ stairs was also not part of the reputation rehabilitation plan – but whenever he did, Ella picked a fight with her mother. This was apparently a watertight guarantee that Beverley would not come near her bedroom. ‘Not until I apologise,’ Ella explained. ‘She wouldn’t give me the satisfaction.’ Arlo had grown up in a house where arguments were loud, instant affairs; Mom got annoyed at Dad, Dad charmed Mom, and then it was over. Ella’s logic was alien. And he felt bad for Beverley.

Do not feel bad for Beverley Franklin. She’s a head melt. Trust me. Who cares if she likes you or not?

It’s all right for you, Leo. Everyone in this town loves you. They cross the road when they see me. They think I’m cursed or a bad omen or something.

Really, Arly? You really think it’s all right for me?

Arlo pushed his best friend from his head – they could talk on the drive to work – just as Ella stepped forward and kissed him on the lips. She slipped her tongue into his mouth and he grinned. Then he remembered the current situation.

‘What time is it? My phone is in my – there they are!’ His trousers were hanging off the couch at the end of the bed, which Ella had informed him was actually a chaise longue. ‘Give anything a French name and Bev will pay three times more for it.’ He pulled on his jeans and found his phone in the back pocket.

8.28 a.m.

Not late, so. Not yet.

Good.

If there was one job he couldn’t afford to mess up, it was this morning’s.

..................

‘What are you doing?! Why would you do that?! What is wrong with you?!’

‘I wasn’t … I’m sorry!’ Amelia shouted back, whipping a blanket from the end of her bed. ‘Don’t freak out, Mum, please! I’m sorry!’

The reverberation in Beverley’s head continued. She looked at her daughter, face caked in make-up, then down at the phone lying on the bed. ‘Jesus Christ!’ she cried. ‘Jesus, Amelia! Jesus Christ!’

‘I’m sorry!’

Beverley took a moment and shut her eyes, only as soon as she did, she was assaulted by the image of her daughter pouting into the camera. Where had she seen such an expression? They flew open again.

‘Who was it for?’

Amelia’s doe eyes were smothered in blue shimmery eyeshadow. Beverley had not known she owned anything so cheap.

She repeated herself. ‘Who was the photo for, Amelia?’

‘I don’t … It wasn’t for anyone.’

Beverley needed to think. She closed her eyes, but there it was again. Was the goddam image tattooed on to her eyelids for all eternity now?

‘Don’t lie to me.’

‘Mum.’

‘Do not lie to me!’

‘I wasn’t sending the photo to anyone,’ she pleaded. ‘I wasn’t. I swear.’

Beverley took a deep breath but did not remove her gaze from her daughter.

‘It was just for me. I just … I wanted to see what it would look like.’

The girl cringed, but she didn’t look away. She was shivering, in spite of the blanket.

After what she’d found on Malachy’s phone in April, Beverley was bound to be sensitive. But not everyone was as perverted as her husband. Young girls experimented. She was only twelve, for God’s sake. Who would she be sending it to?

‘Amelia.’

‘I swear on your life, Mum.’

God help her, but the child appeared to be telling the truth.

‘You swear you weren’t sending it to anyone?’

‘I swear,’ said Amelia emphatically. ‘I wouldn’t. That’s gross.’

Beverley agreed. It was gross.

Amelia’s face was bright red, and Beverley struggled to tell where the excessive blusher ended and the embarrassment began.

‘All right,’ she said. ‘Well, thank God for that.’ She let out a loud sigh. Amelia looked equally relieved. ‘You know you shouldn’t be taking photos like that regardless? You don’t know who could hack into your phone, or if it got stolen, where they might end up. It’s a very stupid thing to do.’

‘I know. I’m sorry.’

Beverley threw back her head. ‘All right.’ She leaned forward so her hands rested on her thighs, then she straightened up again. ‘Okay. Get dressed, quick. And take off that make-up. We have to get going. I need to leave early.’

Amelia hurried back to her vanity table, where she’d thrown her camisole and school shirt.

‘No time for breakfast. I’ll grab some fruit,’ said Beverley, heading for the door. ‘And I’ll meet you out at the car.’

‘Sorry for giving you a fright, Mum.’

Beverley turned back to her daughter, who was attempting a smile. Of course she wasn’t sending erotic photographs of herself out into the world at twelve years of age. Had she that little faith in her own parenting skills? These were the kinds of tender moments she never had with Ella any more. She should cherish them.

‘And I’m sorry I thought the worst,’ she replied, instructing her own face to soften. ‘Forgive me?’

Amelia grinned. ‘Always.’

‘Good.’

Her hand was on the doorknob and she had one foot out in the landing when she heard it. A vibration.

Quick as a flash, she turned.

‘Mum—’

But Beverley was back in the room and over at the bed before Amelia had thought to move.

She looked down at the screen.

Her daughter had one new message.

Beverley did not recognise the App logo, but she knew the sender’s name. There was no need to unlock the phone. The reply was succinct.

Got it!!! Thanks!!!

For the second time that morning, Beverley emitted noises she had not known she was capable of making.

..................

‘Are you nervous?’ asked Ella, sitting beside him on the edge of the bed as he pulled on his boots.

‘About what?’

‘Arlo.’ She grinned.

‘Oh, about Glass Lake!’ he replied, bringing his hand to his forehead and generally making a joke of it even though he’d had an uneasy feeling in his stomach ever since he agreed to take on the job at the school. ‘It’ll be fine.’

‘Of course it will.’

‘I just have to be on time and do the best work I can.’

She kissed him on the cheek. ‘I love you.’

She never seemed to mind that he didn’t say it back. Probably because she knew he did love her – of course he did! – it was just that every time he tried to say it his tongue swelled in his mouth and his head got so hot that he thought it might actually go on fire.

‘It’s just part time, for a couple of weeks,’ he said. ‘I doubt I’ll even see Principal Patterson.’ His stomach flip-flopped. He hoped he wouldn’t see her.

More yelling from the floor below. The only words he could decipher came from Beverley.

‘Well, she’s lucky to have you working there. You’re so good with your hands.’

Arlo blushed, even though Ella hadn’t meant it that way. Although, he hoped she did mean it that way too. He definitely put in the effort.

‘This town, though. Some people can be real jerks.’

‘I know.’

‘They can be totally unfair and terrible …’ She was trying to make him feel better, but the flip-flopping in his stomach had turned to sloshing. ‘… and just tiny-minded gossip lickers.’

‘Gossip lickers?’

‘Or whatever,’ she said. ‘You know what I mean.’

People had only recently stopped sticking ‘For Sale’ signs in the Whiteheads’ front garden. And two weeks ago, while he was walking down Main Street, a man spat at him. He hadn’t told Ella that. He didn’t tell her any more than he had to, in case it sowed seeds of doubt. ‘Yeah. I know.’

‘That’s why we’re getting out,’ she declared, throwing herself back on the bed and pulling him with her. ‘One more year. Less than a year. Woody will be finished primary school in June, and then we go. Right?’

‘Right,’ Arlo agreed, pretending to do the maths even though he knew exactly how far away it was. ‘Eight months.’ One week and four days. ‘Then it’s goodbye Cooney, hello Cork city.’

‘We’ll rent an apartment, overlooking the river.’

‘Or maybe a little house, with two bedrooms,’ he said, lying back beside her. ‘One for us, and one for Woody when he comes to stay, or Amelia.’

‘Amelia can only visit if she promises not to tell Bev our whereabouts.’

‘We’ll get a little dog ...’

‘Called Wisdom,’ said Ella.

‘Or Cooney.’

‘Why would we call our dog Cooney? We want to forget Cooney.’

‘Okay fine, Wisdom,’ said Arlo. ‘And we’ll grow our own vegetables and we’ll have friends over for dinner, and when you come home from university, we’ll sit in our garden—’

‘Or on our balcony.’

‘Right, and we’ll be so happy that we’ll listen to songs about heartbreak and we won’t have a clue what they’re going on about.’

Ella laughed. ‘And then you’ll go to college …’

‘Maybe.’

‘Arlo!’

‘Maybe I will, or maybe I’ll be such a successful handyman by then that I’ll have my own business with lots of employees and I won’t need college.’

‘You’re still planning to re-sit your leaving cert next year, right?’

‘You’re ruining the daydream here, Ella.’

‘Have you applied for the re-sits?’

‘Daydream disappearing. Daydream disappearing,’ he said in an automated voice, moving his arms in a robotic fashion.

‘Have you?’

‘I will.’ He wouldn’t.

He pushed himself up, stood on the bed and peered out the skylight. Beverley’s Range Rover was still in the driveway.

‘Shoes!’ Ella swiped at his feet.

‘Sorry,’ he said, clambering down. ‘Isn’t your mom usually gone by now?’ The only thing that made sneaking into the Franklins’ after midnight slightly less of a gamble was that Ella’s parents had schedules you could set your watch by. Her dad was always gone before they woke, and her mom left to drop Amelia to school at 8.24. Arlo checked his phone again. ‘I need to leave.’

Ella jumped up from the bed and pulled a cardigan from the floor. ‘I’ll go down and distract her,’ she said. ‘And when the coast is clear, I’ll give the signal and you make a run for it.’

She was grinning now. Ella loved the espionage.

Arlo could do without it.

‘Sounds risky,’ he said.

She shrugged. The beige knit slid down her left shoulder. How was her skin so perfect? Like silky milk. Silk milk. That might actually work as a lyric. ‘Let’s just wait it out then,’ she said, throwing herself back down on the bed, ‘and you can be late.’

The mere suggestion brought him out in a sweat.

Arlo groaned. Ella gave a gleeful grin.

‘We just need a signal …’ She looked around the room. Her eyes landed on a poster by the door. ‘Hang ten!’

‘Hang ten?’