Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Titan Books

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Sprache: Englisch

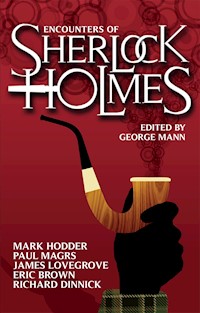

A brand-new collection of Sherlock Holmes stories from a variety of exciting voices in modern horror and steampunk, including James Lovegrove, Paul Magrs and Mark Hodder. Edited by respected anthologist George Mann, and including a story by Mann himself.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 585

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2015

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Coming soon from George Mann and Titan Books

Sherlock Holmes: The Will of the Dead

The Casebook of Newbury & Hobbes

Further Encounters of Sherlock Holmes

ENCOUNTERS OF SHERLOCK HOLMES

BRAND-NEW TALES OF THE GREAT DETECTIVE

Edited by George Mann

TITAN BOOKS

Encounters of Sherlock Holmes

Print edition ISBN: 9781781160039

E-book edition ISBN: 9781781160107

Published by Titan Books

A division of Titan Publishing Group Ltd

144 Southwark Steet, London SE1 0UP

First edition: February 2013

Names, places and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead (except for satirical purposes), is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2013 by the individual contributors.

Introduction copyright © 2013 by George Mann.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library

What did you think of this book? We love to hear from our readers.

Please email us at: [email protected]. or write to us at the above address.

To receive advance information, news, competitions, and exclusive offers online. please sign up for the Titan newsletter on our website: www.titanbooks.com

CONTENTS

Introduction by George Mann

The Loss of Chapter Twenty-One by Mark Hodder

Sherlock Holmes and the Indelicate Widow by Mags L Halliday

The Demon Slasher of Seven Sisters by Cavan Scott

The Post-Modern Prometheus by Nick Kyme

Mrs Hudson at the Christmas Hotel by Paul Magrs

The Case of the Night Crawler by George Mann

The Adventure of the Locked Carriage by Stuart Douglas

The Tragic Affair of the Martian Ambassador by Eric Brown

The Adventure of the Swaddled Railwayman by Richard Dinnick

The Pennyroyal Society by Kelly Hale

The Persian Slipper by Steve Lockley

The Property of a Thief by Mark Wright

Woman’s Work by David Barnett

The Fallen Financier by James Lovegrove

INTRODUCTION

What is it about the character of Sherlock Holmes that has made him such an enduring creation? When Sir Arthur Conan Doyle first sat down to set pen to paper, could he ever have imagined the great legacy his creation would inspire? I do not believe, even in his wildest dreams, that Doyle could have envisioned the manner in which this discourteous, drug-addicted, charismatic genius might develop into one of the world’s best known and most loved fictional creations, let alone the fact his stories would go on to inspire an entire sub-genre of detective fiction.

When Doyle, tired of his character and looking for a reprieve, sent Holmes tumbling to his death over the Reichenbach Falls, the public outcry was so cacophonous that Doyle was forced to raise him from the dead. Yet the public appetite was such that, even after Doyle’s own death in 1930, people continued to hunger for new Holmes adventures.

Consequently, there is a proud legacy of continuing Sherlock Holmes stories, sometimes referred to, perhaps unkindly, as “pastiches”. Indeed, Holmes must, I suspect, be one of the most written-about characters in the English language, and probably in many other languages besides. Books, theatre, radio plays, television shows, films — all have played a part in continuing Doyle’s legacy. Holmes has lived a thousand lifetimes, with twice as many adventures, but still he persists, the master of deduction, the template for most future detectives, a hero whose comforting presence can always be felt, lurking on the edges of popular culture.

Holmes, it seems, is more than just a character. He’s an idea, a cipher; a metaphor for the articulate, intelligent hero that, just like Watson, we all want in our lives.

This volume, then, serves to fulfil that function, at least for a time: to provide the reader with fourteen brand-new tales of Sherlock Holmes. Here we see Holmes encounter strange patchwork men in the dark alleyways of London; meet a dying Sir Richard Francis Burton, who needs his help to locate a missing manuscript; go head to head with AJ. Raffles; unravel a bizarre mystery on the Necropolis Express; meet with H.G. Wells in the strangest of circumstances; unpick a murder in a locked railway carriage; explain the origins of his famous Persian slipper and more. We also see Watson and Mrs Hudson enjoying their own adventures, although Holmes forever looms large, even if he is working quietly to manipulate events from behind the scenes.

I hope you read on to enjoy these “encounters” of Sherlock Holmes. I’ve been privileged enough to be the first to read them as I’ve assembled this volume, and I already know what treats lay in store. So, without further ado, allow me to offer you one simple reassurance — the spirit of Sherlock Holmes lives on in every one of them.

Now go! The game’s afoot!

George Mann

September 2012

THE LOSS OF CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

BY MARK HODDER

Throughout my long acquaintance with Sherlock Holmes I was frequently astonished by the insights I gained into his remarkable mind and the wholly unique manner in which it functioned. Over the years, as these revelations accumulated, I slowly came to understand how his great gift of observational and deductive intellect was also a terrible curse, for it robbed him of those warmer aspects of personality which we depend upon for the establishment and maintenance of friendships and emotional attachments. Indeed, Holmes often appeared to be little more than a machine built to gather and compare facts, calculating probabilities and interconnections until some final set of correspondences was revealed in which lay the solution to whatever problem had been set before him. I found this heartless efficiency disturbing, not only because it so separated him from society, but also because it caused me to often feel regarded as little more than a functional component of his existence. Admittedly, this might be regarded as insecurity on my part, but Holmes did little to assuage it, and I never felt it more deeply than during the case of The Greek Interpreter, when he finally revealed to me that he had a brother.

One night, shortly after the completion of that affair, Holmes and I were sitting up into the early hours, reading and smoking, when I found myself unable to hold my tongue any longer, and, out of the blue, blurted, “Really, Holmes! You are positively inhuman!”

My companion sighed, shifted in his armchair, put aside his book, and levelled his piercing eyes at me, saying nothing.

“Why did you never mention Mycroft before?” I continued. “All this time we’ve known one another, and you kept your brother a secret from me!”

Holmes glanced into his pipe bowl, leaned over and knocked it against the hearth, and set about refilling it. “I didn’t mention him, Watson, simply because there was no reason to do so.”

“No reason? Do you not see that the sharing of personal details about one’s family, upbringing, past and associates establishes deeper bonds of friendship? Is that not reason enough?”

“Do you not consider us friends, then?”

“Of course we’re friends! You purposely overlook my use of the word deeper. Friendship is not a static thing. It must be continually strengthened if it is to survive the naturally degenerative effects of time. You make no effort!”

Holmes waved a hand dismissively. “I have detected no lessening of my attachment to you, despite my apparent neglect.”

“Ha!” I cried out. “Detected! Not felt, but detected! Even in your choice of words you reveal that you do not operate as a normal person. You are thoroughly cold and dispassionate!”

He struck a match and spent a few moments sucking at the stem of his pipe until the tobacco was burning and plumes of blue smoke were curling into the air, then murmured, “An advantage, it would seem. I am not dependent upon the fuel of emotive displays and reassurances.”

I threw down my newspaper in exasperation, jumped to my feet, and paced over to the sideboard to pour myself a drink. “For all your criticism of his sedentary ways, I found Mycroft to be a warmer fellow than you are. Your only passion, Holmes, is the solving of puzzles!”

“Not passion,” he responded. “Vocation. Look out of the window, would you? If I’m not mistaken, a carriage has just pulled up outside. The sound is somewhat muffled. I’ll wager a fog has got up while we’ve been sitting here.”

I frowned, annoyed that our conversation had been interrupted, and pulled aside the curtain. “A peasouper. I can’t see a blessed thing. Great heavens!”

My exclamation came in response to a high-pitched screeching that penetrated both the pall and our windowpane, the words plainly audible. “Absurd! Absurd! It’s a shilling, I tell you! I’ll not be swindled! A shilling! A shilling and not a ha’penny more, confound you!”

I looked back at Holmes, who arched an eyebrow and said, “Down the stairs with you, there’s a good fellow. If paying a cab fare engenders such hysteria, then our street door is about to suffer a dose of unrestrained hammering. Answer it before Mrs Hudson is roused, would you?”

Laying aside my untouched brandy, I left the consulting room, hurried down the staircase, and yanked open the front door just as the first knock impacted against it. A man of about fifty was on our doorstep. He was tiny, barely touching five feet in height, with a fragile-looking slope-shouldered body upon which was mounted a ridiculously outsized head, its bald cranium fringed with bright red hair that curled down around the jawline to form a small unkempt beard. Waving his bowler in the air, he hopped up and down and shrieked, “Help! Help! Sherlock Holmes!”

“Calm yourself!” said I. “Mr Holmes is just upstairs. Allow me to show you up to—”

Before I could finish, the visitor pounced through the door, ducked under my outstretched arm, and scampered up the staircase. “Holmes! Holmes! Murder! Theft! Murder! Help!”

“Hey there! I say!” I protested, setting off in pursuit.

The intruder reached the landing and pounded on the first door he came to, which happened to be that of the consulting room. Holmes called “Come!” and the little man plunged in.

I followed. Holmes hadn’t moved from his armchair and was looking curiously at the apparition that stood twitching and gesticulating wildly in the middle of the room.

“Murder! Theft! Murder! Hurry! We can’t delay the police for much longer!”

I opened my mouth to speak but Holmes stopped me with a small gesture, lay down his pipe, rested his chin on steepled fingers, and continued to watch the bizarre performance.

It occurred to me that our visitor’s face was somewhat familiar, but he was so wildly animated I found it impossible to place him, so waited patiently—as did my colleague—for the histrionics to end.

Three or four minutes of almost incomprehensible jabbering passed before the man threw his hat onto the floor, spread his arms wide, and said, “Well?”

“Well,” Holmes echoed. “Shall we begin with your name, sir?”

“What?” our guest squealed. “What? What? What? My name? Don’t you realise the urgency of the situation? My name? Swinburne. Algernon Swinburne. It’s murder, Holmes! Murder!”

I gasped, and Holmes looked at me enquiringly.

“Mr Swinburne is one of our most accomplished and admired poets,” I said, knowing where that particular art was concerned, my friend’s oddly compartmentalised knowledge didn’t extend far beyond the Petrarch he habitually carried in his coat pocket. “His work is extraordinary.”

“Poetry be damned!” Swinburne shouted. “By heavens, this could kill Burton! You have to help, Holmes! Get up! Out of that chair! We must leave at once! It’s life or death!”

“Who is Burton?” Holmes asked.

Swinburne let loose a piercing scream of frustration, leaped into the air and landed with both feet on his hat, completely flattening it. “Burton! Burton! Sir Richard Francis Burton! Who else would I mean?” He bent, picked up the bowler, punched it back into shape, and suddenly became calm and earnest. “Mr Holmes, please, you must come with me to the St James Hotel right away. I will explain all en route. We cannot lose a further moment!”

Sherlock Holmes stood, cast off his threadbare dressing gown, and kicked the slippers from his feet. “Sir Richard Francis Burton, you say? Very well, Mr Swinburne, Watson and I will accompany you. I ask only that, on the way, you give a full and detailed account of the affair in the most rational manner you can muster. By that, I mean less of the dramatics, if you please.”

“Rational?” Swinburne exclaimed, slapping the dented hat onto his bald cranium. “I assure you, I’m as rational as I’ve ever been!” He turned to me. “Dr Watson, do you have your medical kit?”

I nodded. “Is it required, Mr Swinburne?”

“It may be. Please bring it with you.”

I left the room and entered my bedchamber, where I donned my shoes and jacket and took up my bag. When I returned to the consulting room, Holmes was ready to depart. Swinburne hustled us down the stairs and out into the swirling fog of Baker Street, where he emitted another of his shrill squeals. “Gone! The Brougham! Blast that driver! I knew he couldn’t be trusted! He tried to charge me two and six!”

“That is the approximate fare from the St James Hotel,” Holmes noted.

“Nonsense! A cab ride is a shilling!” Swinburne protested. “The distance is immaterial!”

Holmes and I exchanged a glance. I felt slightly disorientated by the poet’s eccentricity. The detective, by contrast, appeared to be rather amused by it.

Despite the hour and the awful weather, we were able to hail a four-wheeler and were soon rattling southward towards Green Park.

“It is a short journey, Mr Swinburne,” Holmes said. “Please start at the beginning and be concise. What has happened?”

“Murder! Theft!” The poet twitched and jerked spasmodically It was plainly apparent to me that he suffered a congenital excess of electric vitality, but he managed to bring himself under control, took a deep breath, let it out slowly, and continued, “Sir Richard, his wife Isabel, and their personal physician, Dr Grenfell Baker, arrived in London three days ago, having travelled from their home in Trieste, where Burton is consul.”

“Physician?” Holmes asked. “Are the Burtons unwell?”

“Yes. Sir Richard’s heart is giving out. He suffered an attack a few weeks ago and remains frail. But he pushes himself so. He absolutely refuses to rest.”

“And Lady Burton?”

“She’s generally strong but suffers the minor and multiple ailments one must endure with old age.” Swinburne shook his head and murmured:

“Time turns the old days to derision,

Our loves into corpses or wives;

And marriage and death and division

Make barren our lives.”

Holmes clicked his tongue in irritation. “The facts, sir. Nothing more. No embellishments required.”

The little man shuddered from head to foot, slapped his own cheek, tugged at his beard, then went on. “It so happens that our mutual friend, Thomas Bendyshe, was putting up at the St James, too, so the Burtons took a room next to his. Earlier tonight, Isabel went to meet with her sister—”

“Where?” Holmes cut in.

“At Bartolini’s Restaurant in Leicester Square. Dr Baker, meanwhile, visited with his family in Islington, while Sir Richard, Tom Bendyshe and I dined together at the Athenaeum.”

I asked, “For how long have you known the Burtons?”

“Nigh on thirty years,” Swinburne replied.

Holmes muttered, “Immaterial. Do be quiet, Watson.”

I glared at him, but my colleague’s attention was wholly focused upon the poet, who said, “At about nine o’clock, Tom—whose heart is also weak—complained of slight palpitations and left us. Sir Richard and I stayed on at the club until half past eleven. I then accompanied him to the hotel, where he intended to show me a manuscript, of which I shall say more in a moment. When we arrived, the manager was waiting for us in the lobby. He rushed us up to the Burtons’ suite. Apparently, Isabel had returned shortly before us and found Tom Bendyshe lying dead inside it. The aforementioned manuscript was missing. It appears a thief had entered through the window, which had been left open, was interrupted in his work by Tom, and murdered him before fleeing the scene.”

“On which floor is the Burtons’ room?” Holmes asked.

“The fourth. The window is accessible via an exterior metal staircase that runs up to the roof at the rear of the hotel.”

“I see. Why is this not a police matter, Mr Swinburne? Why consult me?”

Swinburne threw his hands into the air. “No! No! Police? Impossible! The hotel manager insisted on calling them but we asked him to delay until I could fetch you. The problem, Mr Holmes, is that we cannot admit the existence of the manuscript to the police.”

“Why not?”

Swinburne levelled his bright green eyes at the detective. “What do you know of Burton, sir?”

Holmes looked at me, said, “Watson?” then sat back and closed his eyes.

“I can speak now?” I asked in an indignant tone.

Holmes flicked his fingers.

“He is—or, rather, was, when in his prime—an explorer,” I said. “He more or less single-handedly opened central Africa, leading to the discovery of the source of the River Nile. He also examined the cultures of West Africa, was one of the first Englishmen to enter forbidden Mecca, and, I believe, was a secret agent for Sir Charles Napier in India.”

“Oh, he’s much more than that,” Swinburne interjected. “Sir Richard is fluent in at least thirty languages. He’s counted as one of the best swordsmen in Europe. He’s a scholar, a disguise artist, an author, a poet, a mesmerist, and an anthropologist.”

Much to my discomfort, a tear rolled down the poet’s cheek.

“But I fear these are his twilight years,” he said. “My friend is not the man he used to be. He’s sixty-seven years old, and the hardships of Africa have caught up with him. But, by God, he’s determined not to go without making one last contribution to man’s knowledge! Two years ago, Mr Holmes, he translated and published an Arabian manuscript entitled The Perfumed Garden of the Cheikh Nefzaoui. It is a treatise concerning the art of physical love between a man and a woman.”

I cleared my throat. “Is it—is it—decent, Mr Swinburne?”

The poet snorted derisively. “Some idiots claim it to be naught but erotica.” He leaned forward. “But do you not agree, Mr Holmes, that through the detailed study of every aspect of human behaviour —every aspect—we can gain a better understanding not only of individual motivations, but also of the racial and cultural proclivities that inform those motivations?”

Holmes opened his eyes and looked a little surprised. “That is a very astute observation, and I agree without reservation.”

“Then you’ll understand the dissatisfaction Sir Richard has felt concerning that volume, for it was published incomplete.”

“In what respect?”

“He’d been unable to locate a version of the work in its original Arabic, and so was forced to translate from a French edition from which the notorious twenty-first chapter had been omitted. That chapter, by itself, is almost the same length as the entirety of the remaining material. It deals with what we English refer to as unnatural vices—that is to say, physical relations between men.”

“Holmes,” I murmured, “I’m not sure we should involve ourselves with—”

“Nonsense!” my friend snapped. “Continue, please, Mr Swinburne.”

“Last year, Sir Richard discovered that an Algerian book dealer owned a copy of the work in its original language and with chapter twenty-one intact. He purchased it, and now intends to re-translate and annotate the entire volume, complete with the missing material. He regards it as his greatest project.”

“And it is this manuscript that has been stolen?” Holmes asked.

“Not the complete thing; just chapter twenty-one. You can see why the police can’t be informed. They couldn’t possibly understand the anthropological value of the document. To them, it would be classed as filth of the worst kind. Sir Richard would be arrested.”

Holmes grunted. “From where, exactly, was the chapter taken?”

“From a travelling trunk in his hotel bedroom.” The poet suddenly slapped a fist into the palm of his hand and cried out, “A curse on Avery, damn him! May the hound rot!”

“You’re getting ahead of yourself,” Holmes said. “Avery?”

Swinburne shook his fist and snarled, “Edward Avery. A bookseller. The Burtons had hardly arrived in London before they learned that the swine has been illegally publishing and selling the earlier edition of The Perfumed Garden. Sir Richard confronted the rogue who, knowing that there could be no legal redress, brazenly offered to publish chapter twenty-one as a supplement. This was refused, of course, and Avery responded by declaring that, one way or another, he would see the chapter in print to his own benefit.”

The little man angrily swept the tears from his cheek. “I lost my good friend Tom Bendyshe tonight, Mr Holmes. I want vengeance. Bring Edward Avery to justice, and restore that chapter to Burton before I lose him as well.”

The carriage came to a jolting halt and the driver shouted down to us, “St James Hotel, gents!”

We disembarked.

“Two and six, please.”

“Again?” Swinburne yelled. “It’s a confounded conspiracy!”

Holmes took the poet by the elbow, dragged him away, and called, “Pay and follow, Watson!”

I fished in my pocket for change, passed the coins up to the cabbie, and chased after my companions.

The St James Hotel, off Piccadilly and at the northeast end of Green Park, was familiar to Holmes and me, as was its manager, Joseph McGarrigle. A concierge ushered us up to the fourth floor and to suite 106, which we found guarded by two constables, both of whom recognised Holmes. They opened the door and we stepped through into a sitting room where Inspector Lestrade of Scotland Yard greeted us somewhat grudgingly. The pallid, rat-faced police detective was standing beside a chair occupied by a large, elderly woman who appeared to be in considerable distress. She was attired in an old-fashioned jacket and voluminous skirt, with a frilly bonnet pinned to her long, tightly wound hair. A large crucifix dangled from the end of her beaded necklace.

I looked from her to the body of a slightly built man sprawled face down between the fireplace and the suite door. His head was turned to one side and a deep and bloody dent was visible between his eyebrows.

Mr McGarrigle was seated at a table by the window.

“Really, Holmes!” Lestrade exclaimed. “This is a very straightforward business. There’s nothing for you here.”

“I shall be the judge of that, if you please, Lestrade,” Holmes replied. He bowed to the woman. “Lady Burton?”

“Yes,” she responded huskily. “Thank you for coming, Mr Holmes. My husband has often expressed a desire to meet you. I wish it could have been under different circumstances.” Holding out a hand to Swinburne, who took it, she added, “Thank you, too, Algy.”

“How is he?” the poet asked.

“Terribly upset.” She sniffed and raised a handkerchief to her eyes.

“Interrupted burglary,” Lestrade announced. “It’s as plain as a pikestaff. Thief came up the stairs outside, climbed in through the window, and was interrupted by Mr Bendyshe. Panicked, killed him, made off. Nothing stolen.”

Sherlock Holmes stepped over to the body and squatted beside it. “How did he get in?”

“I just said. Through the window.”

“Not the burglar, Lestrade. Mr Bendyshe.”

Lady Burton pointed across the chamber at a door opposite the fireplace. “Connecting rooms, Mr Holmes. Thomas was a dear friend. We had that door unlocked so he could come and go as he pleased.”

Lestrade added, “He must have heard movement in here and came to investigate.”

Holmes knelt and bent his head down close to the carpet. “I suppose you’ve been stamping around in your usual clumsy manner?”

“I arrived little more than five minutes ago.”

“Time enough to destroy evidence. I want to turn the body over. Do you object?”

Lestrade hesitated then gave a curt nod of permission.

Holmes indicated that I should draw closer. “Watson, come and help, but watch where you tread. Take the feet.”

I joined him. We carefully rolled the corpse onto its back. I pointed to the head wound and noted, “Not much blood.” Holmes clicked his tongue and impatiently waved me away. He pulled a magnifying lens from inside his jacket and began a meticulous examination of the corpse, lingering over the watch that was hanging by its chain from Bendyshe’s waistcoat pocket. Without looking up, he said, “Tell me what occurred, please, Lady Burton.”

Sir Richard’s wife gave her eyes a final dab with the handkerchief then folded it and pushed it into her sleeve. “I met Blanche—my sister—for dinner. When I came back, I found the room as you see it now, with poor Thomas on the floor. My husband and Algernon returned from their club almost immediately after I had alerted Mr McGarrigle. That is all.”

The hotel manager interjected, “Mr Bendyshe arrived just a few minutes before Lady Burton. He asked if Dr Baker was here. I had been busy overseeing the change of staff to the night shift, and didn’t know whether he was or not. I suppose Mr Bendyshe came looking for him.”

Algernon Swinburne said to Lady Burton, “May I go to Richard?”

She nodded. “Take Dr Watson with you, Algy.” She turned to me. “I’d like your opinion of my husband’s condition, Doctor.”

The poet gestured for me to follow, crossed to a door to the left of the chimneybreast, tapped on the portal, and entered.

I glanced back at Holmes. He was now on his hands and knees, with his nose less than an inch from the carpet, snuffling around like a bloodhound between the dead man and the fireplace.

I stepped into what proved to be the bedroom.

A lean-faced man was sitting in a chair beside the bed. He stood and came forward.

“Dr Watson? I’m Dr Grenfell Baker. I’m pleased to meet you.”

“Um. The pleasure’s mine,” I responded, distractedly. My eyes were not on Baker but on his patient, who was sitting up in the bed.

Sir Richard Francis Burton was glowering at me like the Devil incarnate. Though elderly, white haired, and plainly ill, he was as impressive an individual as I’d ever seen. His deep-set eyes cut me through just as Holmes’ always did, but they had none of the detective’s aloof coldness about them; instead, there was an angry sullenness that both warned and challenged, a look I had often observed in dangerous criminals but which was here supported by a very obvious and ferocious intellect. Burton was a man, I instantly perceived, who’d been tested at every turn, who’d battled his way through one obstacle after another, who had been hurt and defeated and insulted, but who absolutely refused to lie down and take it. That he bore emotional scars was plainly evident—one could see it in that terrible gaze—but he was marked by physical ones, too. A long, savage furrow scored his left cheek; a smaller one, on the opposite side, puckered the skin at the angle of his jaw; and there were pockmarks and old wounds visible all over his face and hands.

Partly concealed by a moustache and short beard, his determined mouth was set hard, though it now twitched at the corners in what might have been an attempted smile.

“Watson, hey?” His voice was deep and gruff. “I have read your accounts with great interest, sir.”

He stretched out his hand to clasp mine. I stepped forward to take it, and, in doing so, suddenly saw through the famous explorer’s brutal appearance and recognised the frail old man beneath. Burton’s eyes were bulging unnaturally, his breathing was too fast and too shallow, his skin felt cold and clammy, and there was a blue tinge to his lips. I had seen the symptoms many times before. His heart was giving out. He was dying.

“Sir Richard,” I said. “It is truly an honour to meet you. As your wife observed, it’s a shame it isn’t under different circumstances. Sherlock Holmes is looking for evidence in the other room and will be with you presently.”

“No,” he growled. “I’ll not receive him as a blasted invalid. I want to watch him work.”

He swung his legs over the side of the bed and pushed himself up.

“For crying out loud!” Dr Baker exclaimed. “Why do you insist on disobeying my every order? Lie down at once!”

“Squawk, squawk!” Burton grumbled. He reached for a robe that hung from the bedpost and shrugged into it. “You’re like a parakeet, Baker! Always making noise! Algy, offer me your shoulder, there’s a good chap.”

Swinburne scuttled forward and gave Burton support.

“Lead on, Dr Watson. You come too, Baker. Perhaps exposure to a scientific intellect will cure you of your quackery.”

Baker and I fell in behind Burton and Swinburne as they slowly shuffled towards the door. Baker leaned close to me and whispered, “First I’m a parakeet, now I’m a duck. He is a perfectly impossible patient.”

No sooner had we entered the lounge than Burton halted in front of us and uttered an oath in Arabic. “Bismillah!”

Looking past him, I saw that Lestrade and McGarrigle were holding Sherlock Holmes by the ankles and dangling him out of the window.

“What in blue blazes?” I cried out, rushing over. I leaned over the sill and saw that the detective was hanging upside down beside the metal staircase. He was holding a lighted match next to one of the points where the structure was bolted into the brickwork.

“Give them a hand hauling me in, Watson!” he called.

I reached down, dug my fingers into the top of his trousers, and helped Lestrade and McGarrigle drag him back to safety.

Burton, who was being fussed over by his wife, steered her back into the chair she’d risen from, then turned to Holmes and said, “I never imagined I might meet you feet first, Mr Holmes. What in heaven’s name were you up to?”

Holmes smiled. “As I am frequently forced to remind Inspector Lestrade, one does not collect evidence by treading on it.” He paced over to Burton and shook him by the hand. “I have read a great many of your accounts, Sir Richard. It is a rare pleasure to meet a man who knows not only how to look, but how to see.”

I gritted my teeth at this. In the cab, Holmes had acted as if he knew little or nothing of the famous explorer when, in truth, he was almost certainly better informed than I. As he so often did, he’d encouraged me to display my knowledge not for information, but for its insufficiency, as if my inadequacies somehow aided him in the clarification of his own thoughts.

“And what I see,” Burton said, “is that you have an unfortunate habit, Mr Holmes. Cocaine, is it? Forgive my bluntness, but you’re a bloody fool. If the damnable stuff doesn’t kill you, it will rob you—” to my utter astonishment, he lifted his hand and used his forefinger to tap Holmes sharply on the forehead “—of that exceptional mind of yours.”

Sherlock Holmes appeared to be so taken aback by this that he was quite lost for words.

“Dick,” Lady Burton objected. “Mr Holmes is here to help.”

My friend recovered himself, bowed his head to her, and said, “It is perfectly all right, madam. Your husband is absolutely correct.” He turned back to Burton. “My eyes?”

“Yes. Your pupils are slightly mismatched in size—the left being dilated—and your lower lids are too dark for your complexion. There are other indications. You are unnaturally gaunt. Your gums are slightly receded. No doubt, if you raised your sleeve, I would see needle marks. What is it, a ten per cent solution taken at regular intervals?”

“Seven,” Holmes answered quietly “And irregular.”

“Ah! So Dr Watson is weaning you off it, then?”

“He is.”

“Then you are blessed with a very good friend indeed.” Burton was still using Swinburne as a physical support. He looked down at the little poet and said, “As am I. Thank you, Algy. I can stand unassisted, I think.”

Dr Baker protested, “You shouldn’t be standing at all.”

“Indeed not!” Lady Burton added.

Burton turned to the hotel manager. “Mr McGarrigle, would you take my wife and Dr Baker downstairs and provide them with a pot of tea? Algy, go with them, please.”

Swinburne flapped his arms. “What? What? What?”

“I would like to speak in private with Mr Holmes. Dr Watson is his trusted confidant, so must stay. Inspector Lestrade represents Scotland Yard and will refuse to go. The rest of you, let us give Mr Holmes some space to do his work. No doubt he is dismayed to have so many people milling around the scene of a crime.” He clapped his hands together. “Out with you! Out! Out! We shall talk later!”

Burton walked unsteadily over to his wife, who had resumed her weeping, and tenderly brushed her cheek with his hand. He kissed her and said softly, “You are tired, darling. Go downstairs. Rest. Don’t worry. I shall be fine, and I won’t be long.”

She clung to him for a moment then reluctantly followed the others. As they were passing through the door, Holmes called, “One moment! Mr McGarrigle, can you tell me how often the exterior staircase is used?”

“It’s not used at all, Mr Holmes,” the hotel manager responded, “and hasn’t been for years. It is unsafe. As I’m sure you saw, the bolts that hold it against the wall are loose.”

When the group had departed, Sir Richard Francis Burton gazed sadly at Bendyshe’s body for a moment before then turning to face Lestrade. “My apologies, Inspector, I did not greet you. What is your opinion of this affair?”

Lestrade hooked his thumbs into his waistcoat. “As I told Holmes, Sir Richard, it is a simple matter. A burglar risked those outside stairs, climbed in through the open window, but was confronted by Mr Bendyshe before he could make off with anything.”

Burton glanced at Holmes, sharing, with that quick look, the secret of the stolen chapter.

“The intruder attacked Bendyshe,” Lestrade went on, “and struck him a fatal blow to the head before escaping back the way he had come.”

“I see. Do you agree with that assessment, Holmes?”

“No, I do not.”

“Good. Neither do I.”

Lestrade emitted a groan, screwed up his eyes, massaged his temples, and whispered, “Oh, spare me! Now there are two of them!”

Burton said, “And you, Dr Watson. Do you see where Lestrade’s theory stumbles and falls?”

I looked at Holmes. He was regarding me with arms folded and an amused twinkle in his eyes. He murmured, “You know my methods, Watson.”

I sighed and cast my eyes over the room.

“The head wound,” I said.

“Ah ha!” Burton responded.

“Bravo!” Holmes added.

“And the position of the body. If Bendyshe entered through the connecting door, why is he now closer to the suite’s entrance? One might suppose that he grappled with the burglar, was forced back across the room, and was murdered where we now see him lying. But there are no signs of a struggle and the wound is on the front of his skull. If he was struck there with enough force to kill him, why did he not fall backwards, as you’d expect? Why is he stretched out face down?”

“Exactly!” Burton exclaimed. “So, Holmes, reveal all! What really happened in this room?”

Sherlock Holmes unfolded his arms and shrugged. “I haven’t the faintest idea.”

Burton, Lestrade and I gaped at him and chorused, “What?”

“I don’t know. I’m baffled. The position of Bendyshe’s body is certainly inconsistent with the picture Lestrade has painted, but I can find no explanation for it. Perhaps, when he was struck, he was clinging to his attacker, who backed away, dragging him forward as he fell, but I’ve found no evidence to support that supposition. I’m sorry, Sir Richard, but, on this occasion, I must give Lestrade his due. What he thinks happened is probably what happened.”

Lestrade clapped his hands together and said, “Finally!”

I saw Burton stagger slightly and, in three rapid strides, rushed to his side and caught him by the elbow. “Enough!” I snapped. “You are in no condition for this, sir. Back to bed, at once. Come!”

The explorer was a big man—in his younger days, he must have been as strong as an ox—but as I guided him slowly back into the bedchamber, with my left hand still gripping his elbow and my right arm about his waist, he seemed to deflate and wither.

I kicked the door shut behind us and whispered, “I don’t know what Holmes is playing at, but I don’t believe a word of it. He’s up to something, of that you can be sure!”

“Bismillah!” Burton croaked, as I helped him out of his gown. “Don’t let him give up on me, Watson. If he can’t recover the manuscript, I might as well die this very night. You have no idea what it means to me.”

I helped him to lie back on the bed, and felt his pulse. It was fluttering wildly. He was struggling for air.

“I’ll do what I can,” I said. “Don’t speak. Lie still and try to regulate your breathing. I’m going to give you a sedative.”

His fingers closed around my wrist. “No! No drugs. The only thing that’ll save me now is chapter twenty-one. My translation will be the crown of my life, Watson! The crown!”

I frowned. “But it’s—it’s pornography, Sir Richard!”

A hoarse chuckle escaped him. It turned into an outburst of coughing. I used my handkerchief to wipe the sweat from his brow and waited for the fit to pass.

“No one understands,” he wheezed. “What is illegal and shocking in 1888 was once the very basis of Plato’s philosophy. What we decry as unnatural and immoral today was considered the noblest form of affection yesterday. Time changes everything, Watson. Everything! And if we refuse to record that which we disapprove of now, then the future will be erected upon foundations so riddled with holes, omissions and misapprehensions that the entire edifice of civilisation might come tumbling down. Dispassionate knowledge! It is—it is—essential!”

A tremor shook him. He moaned and his eyes began to slip up into his head.

“Holmes!” I bellowed. “My bag! For the love of God, bring my bag!”

Seconds later, the door burst open and Sherlock Holmes raced in and handed me my medical kit. Working as rapidly as I could, I loaded a syringe with a solution of morphine and injected it into Burton’s arm. Almost immediately, I observed his muscles relaxing, his breathing became less laboured, and, when I placed my stethoscope to his chest, I found that his heart was beating regularly, though with the slight “echo” I’ve often heard moments after a patient has experienced a heart attack.

“Unconscious,” I said. “It was a close call but he’ll live. For how long I can’t say. What’s your game, Holmes?”

“Later!” the detective replied in a brusque tone. “When you shouted, I sent Lestrade to fetch back Lady Burton. They’ll be here momentarily. We must take this opportunity while we have it.” He crossed to a large Saratoga trunk in the corner of the room, bent over it, and applied his magnifying lens to its lock. “Scratches!” he muttered. “Ha! It gives every appearance of having been picked.” He lifted the lid to reveal books and papers within. “It was from here that chapter twenty-one was removed, but the marks around the lock are an attempted deception. It was opened in the normal manner, with a key.”

“Deception by whom?” I asked.

He straightened. “Have you not seen through the duplicity yet, Watson?”

“Duplicity? No, I can’t say I have. Why did you claim defeat?”

We heard the suite door open and feet crossing the carpet.

“Hush!” Holmes hissed.

Dr Baker, Algernon Swinburne and Lady Burton rushed in, the latter crying out “Dick!” and throwing herself down beside her husband.

“He suffered a mild heart attack,” I told her. “I treated him with morphine. It has stabilised him but he must sleep and avoid any further distress.”

Baker mumbled a thank you and set about examining his patient.

Sherlock Holmes moved over to stand beside Lady Burton and placed a hand gently upon her shoulder. “Madam,” he said. “I must ask something of you.”

She raised her face to him. Tears streamed down her plump cheeks. “What is it, Mr Holmes?”

“I wish you to call upon me at 221b Baker Street tomorrow at ten in the morning. It is of the utmost importance.”

“I can’t leave my husband.”

Holmes looked at me. I said, “The crisis has passed, Lady Burton. I wouldn’t allow you to leave Sir Richard’s side were I not positive that you could afford to do so. The drug will keep him asleep and out of danger while you visit Baker Street.”

Swinburne put in, “I shall remain with him while you are gone, Isabel.”

“But—”

Holmes cut her off. “I must insist upon it.”

She nodded. “Very well. Ten o’clock.”

“Good. Then Watson and I will bid you farewell. Get some sleep, dear lady. You must be exhausted. Mr Swinburne, may I speak with you in the other room for a moment?”

The little man nodded and followed us out. Inspector Lestrade was standing at the suite entrance talking quietly with the two constables. Holmes led Swinburne to the corner farthest from the policemen and the bedroom. He whispered, “Watson and I will take our leave now. This entire matter will be resolved tomorrow and chapter twenty-one will be returned.”

Swinburne gasped. “What? What? What? You’ve solved the case? Will Avery swing for it?”

“Can you call on me at three o’clock tomorrow afternoon?”

The poet nodded eagerly.

Holmes added, “Keep the appointment secret, please. Tell no one. Not even the Burtons.”

We left suite 106 just as a police coroner arrived to remove the body of Thomas Bendyshe.

“You can’t win ’em all, Holmes!” Lestrade called after us.

“Well done, Lestrade,” Holmes responded cheerily. “It’ll certainly raise your stock at the Yard if you find the murderer!” Under his breath, he added, “Not that you will, you insufferable dolt!”

“Explain!” I demanded. “I’m completely in the dark!”

“Tomorrow,” he replied, and I could get nothing more from him.

Mr McGarrigle had one of the hotel’s four-wheelers carry us home. By the time we arrived, it was half past three and I could barely keep my eyes open. I went straight to bed, fell asleep, and was shaken awake, it seemed, after just five minutes.

“Blast it, Holmes, can’t it wait until morning?” I mumbled.

“It is morning,” he said. “Lady Burton is due here in forty minutes.”

I opened an eye and looked him up and down. “Those are the same clothes you wore last night. Have you not been to bed?”

“I’ll sleep when the manuscript is back in Sir Richard’s hands. Rouse yourself! Out of your nest!”

I heaved a sigh, opened my other eye, and sat up. “All right! All right! I’ll be down presently.”

I washed, shaved and dressed, and entered the consulting room just as the doorbell jangled. Holmes was standing before the fireplace with his hands behind his back.

We heard Mrs Hudson ascending the stairs. She knocked and poked her head around the door. “There’s a Lady Isabel Burton to see you, Mr Holmes.”

“Good show! Send her up, Mrs Hudson!”

Moments later, our visitor stepped in. She appeared tired but much recovered after last night’s anxieties, and, in the light of day, I saw she’d once been a tall and handsome woman, though old age had now taken its toll.

Holmes greeted her and waved her to an armchair.

I asked, “How is your husband this morning, Lady Burton?”

“He has not awoken,” she answered, “but Dr Baker assures me his slumber is natural and is the best thing for him.”

“Quite so,” I agreed.

Holmes indicated that I should settle into the other armchair, and, after I had done so, he strode into the middle of the room and turned to face us.

“I wonder, Lady Burton, if there is anything you wish to tell me.”

“In regard to what, Mr Holmes?” she asked.

“Why, in regard to the events of yesterday evening, of course. What else?”

She started to pick nervously at the edge of her shawl. “I rather thought it would be you telling me something about it, sir.”

“If you wish it, I can do so.”

Puzzled, I began, “Holmes—”

He whipped up a hand with the palm facing me and snapped, “Not now, Watson!”

Lady Burton looked at him quizzically. “Well then?”

“Well then,” Holmes said. “Since only chapter twenty-one of the Arabian manuscript was stolen, it’s safe to proceed on the premise that it was removed by someone who knew exactly what they wanted and exactly where it could be found. To reach it, that person had only to do as Inspector Lestrade suggested: ascend the exterior staircase, climb in through the window, cross to the door on their left, enter the bedchamber, and open the trunk.”

“Edward Avery,” Lady Burton muttered. “We did not inform Inspector Lestrade of our suspicions, Mr Holmes, as we thought it better that you approach the bookseller.”

Ignoring her statement, Holmes went on. “The assumption is that, just as the thief entered, Thomas Bendyshe came into the room through the connecting door, which would be to the intruder’s right, immediately spotted him, attempted to apprehend him, and was struck a killing blow to the forehead. But why, then, Lady Burton, did Bendyshe not fall backwards? And why was he at the other end of the room?”

“I don’t know, Mr Holmes.”

“It is because there was no intruder, Edward Avery or otherwise.”

“If there was no burglar,” I protested, “how can the manuscript have gone missing, and who killed Bendyshe?”

“I shall answer the last question first, Watson. No one killed Thomas Bendyshe. He died of natural causes, almost certainly a heart attack. When he fell, he struck his head on the corner of the hearth. You yourself noted the lack of blood. He didn’t bleed because his heart had stopped before he even hit the floor.”

“But his body wasn’t by the fireplace!”

“There were carpet fibres caught up in his watch chain. The only way they could have got there is if his body was dragged across the room. Also, the corner of the hearth was conspicuously cleaner than the rest. It had been wiped down.”

“By whom?” I asked.

“That, Watson, is the question. The metal staircase provides the answer. Observe.”

Holmes turned to his left and held his arms out, angled downward, with his fingers and thumbs curled as if gripping a rail. He marched up and down on the spot, and, while giving this peculiar performance, said, “When one descends a staircase of that sort, one’s hands do not grip the rails to either side tightly, but simply slide along them, to aid balance.” He turned to face the right, raised his arms higher, and mimicked the movements of a person ascending. “But when going up, the hands grip tightly, and one pulls hard in order to relieve some of the effort required by the legs.”

He stopped his mimicry and looked at us. Lady Burton and I returned his gaze blankly. He sighed. “The bolts, Watson! As Mr McGarrigle noted, they were loose in the brickwork. If someone had climbed those metal stairs, the action of their hands would have put great pressure on the bolts and brick dust would have been dislodged around them, from the top section of the staircase in particular, due to the effect of leverage. If, on the other hand, a person had only descended, there would be a lesser amount of dust and it would be more evenly distributed from the topmost to the bottommost bolts. As, indeed, it was.”

Holmes fixed his penetrating eyes upon Lady Burton. “Furthermore, there was a thin film of soot on the stairs, deposited there, no doubt, by our London peasoupers. What say you, madam?”

She said nothing, but her face went white to the lips.

“It had been disturbed,” Holmes went on. “And I noticed that the hem of the dress you were wearing last night was stained with the stuff. Had you gone up the staircase, the stain would have been at the front. It was at the back. Hence, you only went down.”

Lady Burton burst into tears.

Holmes waited patiently. I looked from him to our guest and back again. Slowly, a fog of confusion cleared from my mind, and I realised what had happened.

“You were trying to protect your husband’s reputation!” I exclaimed.

She nodded, and sobbed, “I was the first to return to the hotel that night. Mr McGarrigle was engaged with his staff and did not notice me enter.” She pulled her handkerchief from her sleeve and wiped the tears from her face. “I’d been back less than ten minutes before there came a knock at the door. It was poor Thomas. He was suffering from chest pains and had come looking for Dr Baker.”

I interjected, “But why did he go to the door of your suite rather than entering through the connecting door?”

“He’s known Dick and me for many years,” she replied, “but is not well acquainted with our physician. He wasn’t aware that I was back, and did not want to burst in upon a man who was a virtual stranger to him.”

“And he collapsed in front of you,” Holmes said.

She sniffed and more tears fell. “He suddenly clutched his chest and dropped like a stone. As you say, his head impacted against the hearth, but I’m convinced he died instantly, even before his knees gave way. I rushed to him, found him to be dead, and was about to ring for the hotel manager when—when—”

Another fit of weeping interrupted her discourse. When I moved to comfort her, Holmes made a terse gesture to stop me. We waited, and after a couple of minutes, she started to speak again, though her voice rasped with emotion.

“You must understand,” she said, “there has been a stain on my husband’s character since he was a very young man. He spent his childhood on the continent, and has, in consequence, been regarded by many as somehow un-English. This prejudice increased when he worked for Sir Charles Napier in India and was sent to investigate certain establishments of bad repute. His report was rather too detailed, and when it fell into the wrong hands, it was employed by those jealous of his accomplishments to cast a shadow over him. He has been forced to work long and hard to prove the suspicions unfounded, and has taken risks and endured hardships that would have killed lesser men. And now, just as he’s achieved widespread acclaim for his translation of A Thousand Nights and a Night, this — this — this awful chapter twenty-one! I cannot allow him to be remembered for such a monstrosity. It would eclipse everything good he has ever done!”

Holmes said, “So you saw your chance, dragged Bendyshe away from the fireplace — which you then wiped — took the manuscript, climbed out of the window, descended the metal stairs, and reentered the hotel through the main doors, making sure to be seen by Mr McGarrigle.”

“Yes. I am an old woman, but love for my husband gave me strength enough for all of that.”

“Did it not occur to you that by staging the burglary you could have sent an innocent man to the scaffold?”

“Edward Avery? He is not an innocent man, Mr Holmes. He is pocketing money that should go to Richard. Besides, I knew there’d be nothing but circumstantial evidence to implicate him. His name might have been ruined—which he deserves—but it would have gone no further.”

Sherlock Holmes paced over to the window and looked down at Baker Street. He took his pipe from his pocket and tapped its stem against his chin. “I understand your motives, Lady Burton, but I cannot agree with them. Sir Richard’s achievements will be remembered not because he followed the mob, or did as he was told, or allowed others to make decisions for him, but because he acted independently and used his own judgement. If he believes that chapter twenty-one of The Perfumed Garden will contribute to mankind’s knowledge and understanding, then I cannot doubt him, and neither should you.”

“He regards it as his final project,” I added. “He told me it is his most important work. Do you really intend to deprive him of it?”

She buried her face in her hands. “He will be vilified.”

“Perhaps so,” Holmes murmured. “But he knows the risk and he chooses it. Obviously, he’s prepared to sacrifice his reputation in the short term in order to contribute certain insights to future generations, who might find them less shocking than we do.”

The detective turned away from the window and faced Lady Burton. “I’m afraid I cannot permit your interference. You will tell me where chapter twenty-one is hidden and I will see to it that the material is returned to Sir Richard. Your part in its disappearance will not be mentioned. Not, that is, unless you refuse me.”

Isabel Burton looked at me, as if expecting my support. There was such anguish in her expression, and she possessed such obvious devotion to her spouse, that, for a moment, I was tempted to throw my lot in with her, but then I remembered what Burton had said: If he can’t recover the manuscript, I might as well die this very night!

“You acted with noble intentions,” I said. “But I must agree with my friend. Sir Richard is infirm, but his mind is as sound as a bell, and if he—who has achieved so much—believes the chapter should be translated and published, then it probably should.”

Holmes said, “Where is the manuscript, Lady Burton?”

She slumped in her seat. Her mouth worked silently for a moment. She whispered, “I wrapped it in a pillowcase and threw it into a coalbunker by the mews behind the hotel.”

“Watson!” Holmes barked. “Leave immediately. Find it!”

I stood, put my hand on Lady Burton’s arm, murmured, “He was, is, and shall always be regarded as a great man,” and departed.

A fast hansom delivered me to the St James Hotel, and, within minutes, while the carriage waited, I’d located the coalbunker and discovered the package inside it. I returned to Baker Street. Holmes was alone, sitting in a haze of tobacco smoke.

“A truly remarkable woman, Watson!” he declared. “Such loyalty is commendable, don’t you think?”

I left chapter twenty-one on the table, crossed to the sideboard, and drank the brandy I’d poured the night before. “Even if it leads to misjudged actions, Holmes?”

“Ha! She allowed her faith in her husband’s intellect to be adversely influenced by emotion.”

“Her love for him?”

“No. Her fear that she’d outlive him and have to endure alone the ruination of his good name.”

I shook my head. “Poor woman. It must be exceedingly difficult to live in the shadow of such a giant.”

My friend gave me a peculiar look. “Those who do, and who provide support and stability, are the very best of us all.”

For the next few hours, I read and dozed while Holmes stared into space and filled the room with noxious tobacco fumes. Neither of us touched chapter twenty-one.

At three o’clock, Algernon Swinburne arrived and Holmes handed the manuscript to him.

The little poet leaped into the air and emitted a triumphant squeal. “How, Holmes? Who? Why? Avery?”

“No, Mr Swinburne, the bookseller was not involved. I can say nothing more. Take the chapter and return it to Sir Richard. Inform him that it was my pleasure to assist him, and there is no fee.”

“Thank you, Holmes! Thank you!”

With that, Swinburne left us and, I would like to say, the affair of the missing chapter came to a satisfying conclusion. Except, it didn’t.

One evening, nearly three years later, in July of 1891, I was dining alone in the Athenaeum. Sherlock Holmes was dead—or so I believed— having plunged with Professor Moriarty into the Reichenbach Falls, and I was still in the throes of a deep depression.

I had just finished my meal when a man, uninvited, pulled out a chair and sat at my table.

“My condolences, Dr Watson,” he said.

“Mr Swinburne! It is good to see you!” I gripped the little poet’s hand, and, remembering that Sir Richard Francis Burton had passed away in Trieste nine months previously, added, “We have both suffered a terrible loss.”

He nodded, swallowed, then bunched his fingers into a fist and slammed it down on the table, causing the cutlery and crockery to rattle. “Did you hear what she did?”

“Yes.”

It had been in all the newspapers. Burton had completed his translation, which he’d retitled The Scented Garden, but a heart attack had taken him before it could be published, and, in the wake of his death, Lady Burton had gathered together all his papers, correspondence, and journals, and made a bonfire of them. Into this, she threw her husband’s magnum opus.

“It was his masterpiece,” Swinburne said. “And she destroyed it. I will never forgive her. I will never speak to her again.”

We ordered coffee, and for many minutes sat in silence, contemplating, remembering, and mourning.

Swinburne suddenly stated, “He was not an easy man to be with.”

“Nor Sherlock Holmes,” said I.

“He was bullish and provocative, argumentative and occasionally brutal in his choice of words. But here is the strange thing, Dr Watson: whenever I was in his company, no matter how awkward and frustrating a companion he may have been, I never felt so thoroughly engaged with the business of living.”

I nodded. “Yes, Mr Swinburne. I know exactly what you mean.”

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Mark Hodder is the author of the Philip K. Dick Award-winning series of Burton and Swinburne adventures, beginning with The Strange Affair of Spring Heeled Jack, in which the famous explorer and poet play Holmes and Watson-like roles in slightly twisted versions of true history. Hodder has also written A Red Sun Also Rises, an homage to the nineteenth-century novel and the planetary romances of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Born in Southampton, Hodder worked for many years in London, including a five-year stint at the BBC, but now lives in Valencia, Spain, where he writes on a full-time basis. He collects and preserves Sexton Blake stories, and is a fan of the old ITC TV shows, such as The Persuaders, The Champions, Department S, and The Prisoner.

SHERLOCK HOLMES AND THE INDELICATE WIDOW

BY MAGS L HALLIDAY

I