Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Tacet Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Serie: Essential Novelists

- Sprache: Englisch

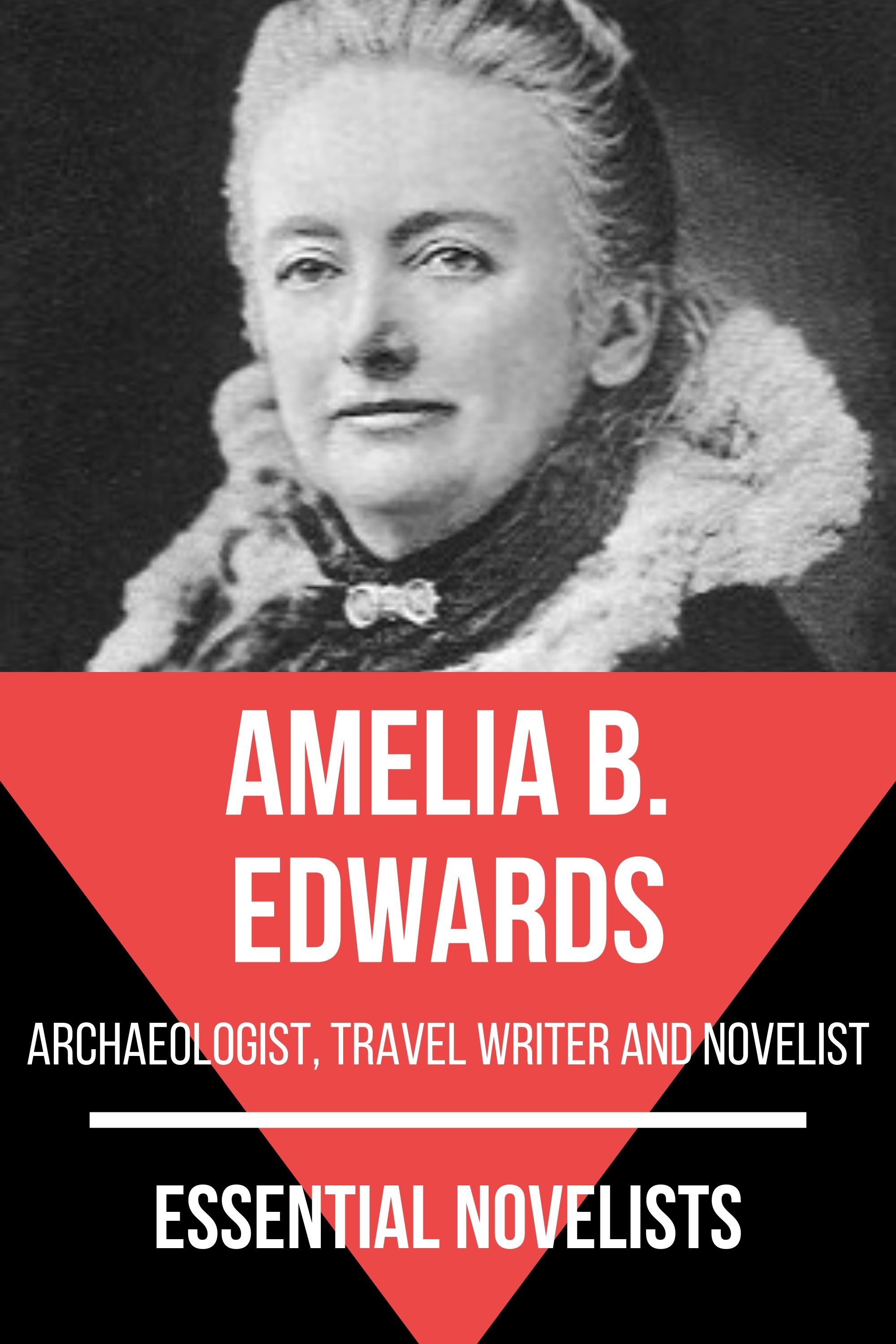

Welcome to the Essential Novelists book series, were we present to you the best works of remarkable authors. For this book, the literary critic August Nemo has chosen the two most important and meaningful novels of Amelia B. Edwardswhich areIn the Days of My Youth and Monsieur Maurice. Amelia B. Edwards was an English writer and Egyptologist that showed writing talent at a young age, publishing poetry at age 7 and her first story at age 12. Novels selected for this book: - In the Days of My Youth - Monsieur MauriceThis is one of many books in the series Essential Novelists. If you liked this book, look for the other titles in the series, we are sure you will like some of the authors.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 861

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Table of Contents

Title Page

Author

In the Days of My Youth

Monsieur Maurice

About the Publisher

Author

AMELIA ANN BLANFORD Edwards (7 June 1831 – 15 April 1892), also known as Amelia B. Edwards, was an English novelist, journalist, traveller and Egyptologist. Her most successful literary works included the ghost story "The Phantom Coach" (1864), the novels Barbara's History (1864) and Lord Brackenbury (1880), and the Egyptian travelogue A Thousand Miles up the Nile (1877). In 1882, she co-founded the Egypt Exploration Fund. She also edited a poetry anthology[2] published in 1878.

Born in London to an Irish mother and a father who had been a British Army officer before becoming a banker, Edwards was educated at home by her mother and showed early promise as a writer. She published her first poem at the age of seven and her first story at the age of twelve. Thereafter came a variety of poetry, stories, and articles in several periodicals, including Chambers's Journal, Household Words, and All the Year Round. She also wrote for the Saturday Review and the Morning Post.

In addition, Edwards became an artist and would illustrate some of her own writings. She would also paint scenes from other books she had read.[6] She was talented enough at the age of 12 to catch the eye of George Cruikshank, who went as far to offer to teach her, but this talent was not supported by Edwards's parents, who saw it as a lesser profession and the artist way of life as scandalous. This negative decision haunted Edwards through her early life. She would wonder frequently whether art would not have been her true calling.

Thirdly, Edwards took up composing and performing music for some years, until she suffered a bout of Typhus in 1849 that was followed by a frequently sore throat, which made it hard for her to sing, caused her to lose interest in music and even regret the time she had spent on opera. Other interests she pursued included pistol shooting, riding, and mathematics.

In the Days of My Youth

CHAPTER I.

MY BIRTHPLACE AND PARENTAGE.

––––––––

Dolce sentier,

Colle, che mi piacesti,

Ov'ancor per usanza amor mi mena!

PETRARCH.

––––––––

SWEET, SECLUDED, SHADY Saxonholme! I doubt if our whole England contains another hamlet so quaint, so picturesquely irregular, so thoroughly national in all its rustic characteristics. It lies in a warm hollow environed by hills. Woods, parks and young plantations clothe every height and slope for miles around, whilst here and there, peeping down through green vistas, or towering above undulating seas of summer foliage, stands many a fine old country mansion, turreted and gabled, and built of that warm red brick that seems to hold the light of the sunset long after it has faded from the rest of the landscape. A silver thread of streamlet, swift but shallow, runs noisily through the meadows beside the town and loses itself in the Chad, about a mile and a half farther eastward. Many a picturesque old wooden bridge, many a foaming weir and ruinous water-mill with weedy wheel, may be found scattered up and down the wooded banks of this little river Chad; while to the brook, which we call the Gipstream, attaches a vague tradition of trout.

The hamlet itself is clean and old-fashioned, consisting of one long, straggling street, and a few tributary lanes and passages. The houses some few years back were mostly long and low-fronted, with projecting upper stories, and diamond-paned bay-windows bowered in with myrtle and clematis; but modern improvements have done much of late to sweep away these antique tenements, and a fine new suburb of Italian and Gothic villas has sprung up, between the town and the railway station. Besides this, we have a new church in the mediæval style, rich in gilding and colors and thirteenth-century brass-work; and a new cemetery, laid out like a pleasure-garden; and a new school-house, where the children are taught upon a system with a foreign name; and a Mechanics' Institute, where London professors come down at long intervals to expound popular science, and where agriculturists meet to discuss popular grievances.

At the other extremity of the town, down by Girdlestone Grange, an old moated residence where the squire's family have resided these four centuries past, we are full fifty years behind our modern neighbors. Here stands our famous old "King's-head Inn," a well-known place of resort so early as the reign of Elizabeth. The great oak beside the porch is as old as the house itself; and on the windows of a little disused parlor overlooking the garden may still be seen the names of Sedley, Rochester and other wits of the Restoration. They scrawled those autographs after dinner, most likely, with their diamond rings, and went reeling afterwards, arm-in-arm, along the village street, singing and swearing, and eager for adventures—as gentlemen were wont to be in those famous old times when they drank the king's health more freely than was good for their own.

Not far from the "King's Head," and almost hidden by the trees which divide it from the road, stands an ancient charitable institution called the College—quadrangular, mullion-windowed, many-gabled, and colonized by some twenty aged people of both sexes. At the back of the college, adjoining a space of waste ground and some ruined cloisters, lies the churchyard, in the midst of which, surrounded by solemn yews and mouldering tombs, stands the Priory Church. It is a rare old church, founded, according to the county history, in the reign of Edward the Confessor, and entered with a full description in Domesday Book. Its sculptured monuments and precious brasses, its Norman crypt, carved stalls and tattered banners drooping over faded scutcheons, tell all of generations long gone by, of noble families extinct, of gallant deeds forgotten, of knights and ladies remembered only by the names above their graves. Amongst these, some two or three modest tablets record the passing away of several generations of my own predecessors—obscure professional men for the most part, of whom some few became soldiers and died abroad.

In close proximity to the church stands the vicarage, once the Priory; a quaint old rambling building, surrounded by magnificent old trees. Here for long centuries, a tribe of rooks have held undisputed possession, filling the boughs with their nests and the air with their voices, and, like genuine lords of the soil, descending at their own grave will and pleasure upon the adjacent lands.

Picturesque and mediæval as all these old buildings and old associations help to make us, we of Saxonholme pretend to something more. We claim to be, not only picturesque but historic. Nay, more than this—we are classical. WE WERE FOUNDED BY THE ROMANS. A great Roman road, well known to antiquaries, passed transversely through the old churchyard. Roman coins and relics, and fragments of tesselated pavement, have been found in and about the town. Roman camps may be traced on most of the heights around. Above all, we are said to be indebted to the Romans for that inestimable breed of poultry in right of which we have for years carried off the leading prizes at every poultry-show in the county, and have even been enabled to make head against the exaggerated pretensions of modern Cochin-China interlopers.

Such, briefly sketched, is my native Saxonholme. Born beneath the shade of its towering trees and overhanging eaves, brought up to reverence its antiquities, and educated in the love of its natural beauties, what wonder that I cling to it with every fibre of my heart, and even when affecting to smile at my own fond prejudice, continue to believe it the loveliest peacefulest nook in rural England?

My father's name was John Arbuthnot. Sprung from the Arbuthnots of Montrose, we claim to derive from a common ancestor with the celebrated author of "Martinus Scriblerus." Indeed, the first of our name who settled at Saxonholme was one James Arbuthnot, son to a certain nonjuring parson Arbuthnot, who lived and died abroad, and was own brother to that famous wit, physician and courtier whose genius, my father was wont to say, conferred a higher distinction upon our branch of the family than did those Royal Letters-Patent whereby the elder stock was ennobled by His most Gracious Majesty King George the Fourth, on the occasion of his visit to Edinburgh in 1823. From this James Arbuthnot (who, being born and bred at St. Omer, and married, moreover, to a French wife, was himself half a Frenchman) we Saxonholme Arbuthnots were the direct descendants.

Our French ancestress, according to the family tradition, was of no very exalted origin, being in fact the only daughter and heiress of one Monsieur Tartine, Perruquier in chief at the Court of Versailles. But what this lady wanted in birth, she made up in fortune, and the modest estate which her husband purchased with her dowry came down to us unimpaired through five generations. In the substantial and somewhat foreign-looking red-brick house which he built (also, doubtless, with Madame's Louis d'ors) we, his successors, had lived and died ever since. His portrait, together with the portraits of his wife, son, and grandson, hung on the dining-room walls; and of the quaint old spindle-legged chairs and tables that had adorned our best rooms from time immemorial, some were supposed to date as far back as the first founding and furnishing of the house.

It is almost needless to say that the son of the non-juror and his immediate posterity were staunch Jacobites, one and all. I am not aware that they ever risked or suffered anything for the cause; but they were not therefore the less vehement. Many were the signs and tokens of that dead-and-gone political faith which these loyal Arbuthnots left behind them. In the bed-rooms there hung prints of King James the Second at the Battle of the Boyne; of the Royal Martyr with his plumed hat, lace collar, and melancholy fatal face; of the Old and Young Pretenders; of the Princess Louisa Teresia, and of the Cardinal York. In the library were to be found all kinds of books relating to the career of that unhappy family: "Ye Tragicall History of ye Stuarts, 1697;" "Memoirs of King James II., writ by his own hand;" "La Stuartide," an unfinished epic in the French language by one Jean de Schelandre; "The Fate of Majesty exemplified in the barbarous and disloyal treatment (by traitorous and undutiful subjects) of the Kings and Queens of the Royal House of Stuart," genealogies of the Stuarts in English, French and Latin; a fine copy of "Eikon Basilike," bound in old red morocco, with the royal arms stamped upon the cover; and many other volumes on the same subject, the names of which (although as a boy I was wont to pore over their contents with profound awe and sympathy) I have now for the most part forgotten.

Most persons, I suppose, have observed how the example of a successful ancestor is apt to determine the pursuits of his descendants down to the third and fourth generations, inclining the lads of this house to the sea, and of that to the bar, according as the great man of the family achieved his honors on shipboard, or climbed his way to the woolsack. The Arbuthnots offered no exception to this very natural law of selection. They could not help remembering how the famous doctor had excelled in literature as in medicine; how he had been not only Physician in Ordinary to Queen Anne and Prince George of Denmark, but a satirist and pamphleteer, a wit and the friend of wits—of such wits as Pope and Swift, Harley and Bolingbroke. Hence they took, as it were instinctively, to physic and the belles lettres, and were never without a doctor or an author in the family.

My father, however, like the great Martinus Scriblerus, was both doctor and author. And he was a John Arbuthnot. And to carry the resemblance still further, he was gifted with a vein of rough epigrammatic humor, in which it pleased his independence to indulge without much respect of persons, times, or places. His tongue, indeed, cost him some friends and gained him some enemies; but I am not sure that it diminished his popularity as a physician. People compared him to Abernethy, whereby he was secretly flattered. Some even went so far as to argue that only a very clever man could afford to be a bear; and I must say that he pushed this conclusion to its farthest limit, showing his temper alike to rich and poor upon no provocation whatever. He cared little, to be sure, for his connection. He loved the profession theoretically, and from a scientific point of view; but he disliked the drudgery of country practice, and stood in no need of its hardly-earned profits. Yet he was a man who so loved to indulge his humor, no matter at what cost, that I doubt whether he would have been more courteous had his bread depended on it. As it was, he practised and grumbled, snarled at his patients, quarrelled with the rich, bestowed his time and money liberally upon the poor, and amused his leisure by writing for a variety of scientific periodicals, both English and foreign.

Our home stood at the corner of a lane towards the eastern extremity of the town, commanding a view of the Squire's Park, and a glimpse of the mill-pool and meadows in the valley beyond. This lane led up to Barnard's Green, a breezy space of high, uneven ground dedicated to fairs, cricket matches, and travelling circuses, whence the noisy music of brass bands, and the echoes of alternate laughter and applause, were wafted past our windows in the summer evenings. We had a large garden at the back, and a stable up the lane; and though the house was but one story in height, it covered a considerable space of ground, and contained more rooms than we ever had occasion to use. Thus it happened that since my mother's death, which took place when I was a very little boy, many doors on the upper floor were kept locked, to the undue development of my natural inquisitiveness by day, and my mortal terror when sent to bed at night. In one of these her portrait still hung above the mantelpiece, and her harp stood in its accustomed corner. In another, which was once her bedroom, everything was left as in her lifetime, her clothes yet hanging in the wardrobe, her dressing-case standing upon the toilet, her favorite book upon the table beside the bed. These things, told to me by the servants with much mystery, took a powerful hold upon my childish imagination. I trembled as I passed the closed doors at dusk, and listened fearfully outside when daylight gave me courage to linger near them. Something of my mother's presence, I fancied, must yet dwell within—something in her shape still wander from room to room in the dim moonlight, and echo back the sighing of the night winds. Alas! I could not remember her. Now and then, as if recalled by a dream, some broken and shadowy images of a pale face and a slender hand floated vaguely through my mind; but faded even as I strove to realize them. Sometimes, too, when I was falling off to sleep in my little bed, or making out pictures in the fire on a winter evening, strange fragments of old rhymes seemed to come back upon me, mingled with the tones of a soft voice and the haunting of a long-forgotten melody. But these, after all, were yearnings more of the heart than the memory:—

"I felt a mother-want about the world.

And still went seeking."

To return to my description of my early home:—the two rooms on either side of the hall, facing the road, were appropriated by my father for his surgery and consulting-room; while the two corresponding rooms at the back were fitted up as our general reception-room, and my father's bed-room. In the former of these, and in the weedy old garden upon which it opened, were passed all the days of my boyhood.

It was my father's good-will and pleasure to undertake the sole charge of my education. Fain would I have gone like other lads of my age to public school and college; but on this point, as on most others, he was inflexible. Himself an obscure physician in a remote country town, he brought me up with no other view than to be his own successor. The profession was not to my liking. Somewhat contemplative and nervous by nature, there were few pursuits for which I was less fitted. I knew this, but dared not oppose him. Loving study for its own sake, and trusting to the future for some lucky turn of destiny, I yielded to that which seemed inevitable, and strove to make the best of it.

Thus it came to pass that I lived a quiet, hard-working home life, while other boys of my age were going through the joyous experience of school, and chose my companions from the dusty shelves of some three or four gigantic book-cases, instead of from the class and the playground. Not that I regret it. I believe, on the contrary, that a boy may have worse companions than books and busts, employments less healthy than the study of anatomy, and amusements more pernicious than Shakespeare and Horace. Thank Heaven! I escaped all such; and if, as I have been told, my boyhood was unboyish, and my youth prematurely cultivated, I am content to have been spared the dangers in exchange for the pleasures of a public school.

I do not, however, pretend to say that I did not sometimes pine for the recreations common to my age. Well do I remember the manifold attractions of Barnard's Green. What longing glances I used to steal towards the boisterous cricketers, when going gravely forth upon a botanical walk with my father! With what eager curiosity have I not lingered many a time before the entrance to a forbidden booth, and scanned the scenic advertisement of a travelling show! Alas! how the charms of study paled before those intervals of brief but bitter temptation! What, then, was pathology compared to the pig-faced lady, or the Materia Medica to Smith's Mexican Circus, patronized by all the sovereigns of Europe? But my father was inexorable. He held that such places were, to use his own words, "opened by swindlers for the ruin of fools," and from one never-to-be-forgotten hour, when he caught me in the very act of taking out my penny-worth at a portable peep-show, he bound me over by a solemn promise (sealed by a whipping) never to repeat the offence under any provocation or pretext whatsoever. I was a tiny fellow in pinafores when this happened, but having once pledged my word, I kept it faithfully through all the studious years that lay between six and sixteen.

At sixteen an immense crisis occurred in my life. I fell in love. I had been in love several times before—chiefly with the elder pupils at the Miss Andrews' establishment; and once (but that was when I was very young indeed) with the cook. This, however, was a much more romantic and desperate affair. The lady was a Columbine by profession, and as beautiful as an angel. She came down to our neighborhood with a strolling company, and performed every evening, in a temporary theatre on the green, for nearly three weeks. I used to steal out after dinner when my father was taking his nap, and run the whole way, that I might be in time to see the object of my adoration walking up and down the platform outside the booth before the performances commenced. This incomparable creature wore a blue petticoat spangled with tinfoil, and a wreath of faded poppies. Her age might have been about forty. I thought her the loveliest of created beings. I wrote sonnets to her—dozens of them—intending to leave them at the theatre door, but never finding the courage to do it. I made up bouquets for her, over and over again, chosen from the best flowers in our neglected garden; but invariably with the same result. I hated the harlequin who presumed to put his arm about her waist. I envied the clown, whom she condescended to address as Mr. Merriman. In short, I was so desperately in love that I even tried to lie awake at night and lose my appetite; but, I am ashamed to own, failed signally in both endeavors.

At length I wrote to her. I can even now recall passages out of that passionate epistle. I well remember how it took me a whole morning to write it; how I crammed it with quotations from Horace; and how I fondly compared her to most of the mythological divinities. I then copied it out on pale pink paper, folded it in the form of a heart, and directed it to Miss Angelina Lascelles, and left it, about dusk, with the money-taker at the pit door. I signed myself, if I remember rightly, Pyramus. What would I not have given that evening to pay my sixpence like the rest of the audience, and feast my eyes upon her from some obscure corner! What would I not have given to add my quota to the applause!

I could hardly sleep that night; I could hardly read or write, or eat my breakfast the next morning, for thinking of my letter and its probable effect. It never once occurred to me that my Angelina might possibly find it difficult to construe Horace. Towards evening, I escaped again, and flew to Barnard's Green. It wanted nearly an hour to the time of performance; but the tuning of a violin was audible from within, and the money-taker was already there with his pipe in his mouth and his hands in his pockets. I had no courage to address that functionary; but I lingered in his sight and sighed audibly, and wandered round and round the canvas walls that hedged my divinity. Presently he took his pipe out of, his mouth and his hands out of his pockets; surveyed me deliberately from head to foot, and said:—

"Hollo there! aint you the party that brought a three-cornered letter here last evening!"

I owned it, falteringly.

He lifted a fold in the canvas, and gave me a gentle shove between the shoulders.

"Then you're to go in," said he, shortly. "She's there, somewhere. You're sure to find her."

The canvas dropped behind me, and I found myself inside. My heart beat so fast that I could scarcely breathe. The booth was almost dark; the curtain was down; and a gentleman with striped legs was lighting the footlamps. On the front pit bench next the orchestra, discussing a plate of bread and meat and the contents of a brown jug, sat a stout man in shirt-sleeves and a woman in a cotton gown. The woman rose as I made my appearance, and asked, civilly enough, whom I pleased to want.

I stammered the name of Miss Angelina Lascelles.

"Miss Lascelles!" she repeated. "I am Miss Lascelles," Then, looking at me more narrowly, "I suppose," she added, "you are the little boy that brought the letter?"

The little boy that brought the letter! Gracious heavens! And this middle-aged woman in a cotton gown—was she the Angelina of my dreams! The booth went round with me, and the lights danced before my eyes.

"If you have come for an answer," she continued, "you may just say to your Mr. Pyramid that I am a respectable married woman, and he ought to be ashamed of himself—and, as for his letter, I never read such a heap of nonsense in my life! There, you can go out by the way you came in, and if you take my advice, you won't come back again!"

How I looked, what I said, how I made my exit, whether the doorkeeper spoke to me as I passed, I have no idea to this day. I only know that I flung myself on the dewy grass under a great tree in the first field I came to, and shed tears of such shame, disappointment, and wounded pride, as my eyes had never known before. She had called me a little boy, and my letter a heap of nonsense! She was elderly—she was ignorant—she was married! I had been a fool; but that knowledge came too late, and was not consolatory.

By-and-by, while I was yet sobbing and disconsolate, I heard the drumming and fifing which heralded the appearance of the Corps Dramatique on the outer platform. I resolved to see her for the last time. I pulled my hat over my eyes, went back to the Green, and mingled with the crowd outside the booth. It was growing dusk. I made my way to the foot of the ladder, and observed her narrowly. I saw that her ankles were thick, and her elbows red. The illusion was all over. The spangles had lost their lustre, and the poppies their glow. I no longer hated the harlequin, or envied the clown, or felt anything but mortification at my own folly.

"Miss Angelina Lascelles, indeed!" I said to myself, as I sauntered moodily home. "Pshaw! I shouldn't wonder if her name was Snooks!"

CHAPTER II.

THE LITTLE CHEVALIER.

––––––––

A mere anatomy, a mountebank,

A threadbare juggler.

Comedy of Errors.

Nay, then, he is a conjuror.

Henry VI.

––––––––

MY ADVENTURE WITH MISS Lascelles did me good service, and cured me for some time, at least, of my leaning towards the tender passion. I consequently devoted myself more closely than ever to my studies—indulged in a passing mania for genealogy and heraldry—began a collection of local geological specimens, all of which I threw away at the end of the first fortnight—and took to rearing rabbits in an old tumble-down summer-house at the end of the garden. I believe that from somewhere about this time I may also date the commencement of a great epic poem in blank verse, and Heaven knows how many cantos, which was to be called the Columbiad. It began, I remember, with a description of the Court of Ferdinand and Isabella, and the departure of Columbus, and was intended to celebrate the discovery, colonization, and subsequent history of America. I never got beyond ten or a dozen pages of the first canto, however, and that Transatlantic epic remains unfinished to this day.

The great event which I have recorded in the preceding chapter took place in the early summer. It must, therefore, have been towards the close of autumn in the same year when my next important adventure befell. This time the temptation assumed a different shape.

Coming briskly homewards one fine frosty morning after having left a note at the Vicarage, I saw a bill-sticker at work upon a line of dead wall which at that time reached from the Red Lion Inn to the corner of Pitcairn's Lane. His posters were printed in enormous type, and decorated with a florid bordering in which the signs of the zodiac conspicuously figured Being somewhat idly disposed, I followed the example of other passers-by, and lingered to watch the process and read the advertisement. It ran as follows:——

MAGIC AND MYSTERY! MAGIC AND MYSTERY!

M. LE CHEVALIER ARMAND PROUDHINE, (of Paris) surnamed

THE WIZARD OF THE CAUCASUS,

Has the honor to announce to the Nobility and Gentry of Saxonholme and its vicinity, that he will, to-morrow evening (October—, 18—), hold his First

SOIREE FANTASTIQUE

IN

THE LARGE ROOM OF THE RED LION HOTEL.

ADMISSION 1s. RESERVED SEATS 2s. 6d.

To commence at Seven.

N.B.—The performance will include a variety of new and surprising feats of Legerdemain never before exhibited.

A soirée fantastique! what would I not give to be present at a soirée fantastique! I had read of the Rosicrucians, of Count Cagliostro, and of Doctor Dee. I had peeped into more than one curious treatise on Demonology, and I fancied there could be nothing in the world half so marvellous as that last surviving branch of the Black Art entitled the Science of Legerdemain.

What if, for this once, I were to ask leave to be present at the performance? Should I do so with even the remotest chance of success? It was easier to propound this momentous question than to answer it. My father, as I have already said, disapproved of public entertainments, and his prejudices were tolerably inveterate. But then, what could be more genteel than the programme, or more select than the prices? How different was an entertainment given in the large room of the Red Lion Hotel to a three-penny wax-work, or a strolling circus on Barnard's Green! I had made one of the audience in that very room over and over again when the Vicar read his celebrated "Discourses to Youth," or Dr. Dunks came down from Grinstead to deliver an explosive lecture on chemistry; and I had always seen the reserved seats filled by the best families in the neighborhood. Fully persuaded of the force of my own arguments, I made up my mind to prefer this tremendous request on the first favorable opportunity, and so hurried home, with my head full of quite other thoughts than usual.

My father was sitting at the table with a mountain of books and papers before him. He looked up sharply as I entered, jerked his chair round so as to get the light at his back, put on his spectacles, and ejaculated:—

"Well, sir!"

This was a bad sign, and one with which I was only too familiar. Nature had intended my father for a barrister. He was an adept in all the arts of intimidation, and would have conducted a cross-examination to perfection. As it was, he indulged in a good deal of amateur practice, and from the moment when he turned his back to the light and donned the inexorable spectacles, there was not a soul in the house, from myself down to the errand-boy, who was not perfectly aware of something unpleasant to follow.

"Well, sir!" he repeated, rapping impatiently upon the table with his knuckles.

Having nothing to reply to this greeting, I looked out of the window and remained silent; whereby, unfortunately. I irritated him still more.

"Confound you, sir!" he exclaimed, "have you nothing to say?"

"Nothing," I replied, doggedly.

"Stand there!" he said, pointing to a particular square in the pattern of the carpet. "Stand there!"

I obeyed.

"And now, perhaps, you will have the goodness to explain what you have been about this morning; and why it should have taken you just thirty-seven minutes by the clock to accomplish a journey which a tortoise—yes, sir, a tortoise,—might have done in less than ten?"

I gravely compared my watch with the clock before replying.

"Upon my word, sir," I said, "your tortoise would have the advantage of me."

"The advantage of you! What do you mean by the advantage of you, you affected puppy?"

"I had no idea," said I, provokingly, "that you were in unusual haste this morning."

"Haste!" shouted my father. "I never said I was in haste. I never choose to be in haste. I hate haste!"

"Then why..."

"Because you have been wasting your time and mine, sir," interrupted he. "Because I will not permit you to go idling and vagabondizing about the village."

My sang froid was gone directly.

"Idling and vagabondizing!" I repeated angrily. "I have done nothing of the kind. I defy you to prove it. When have you known me forget that I am a gentleman?"

"Humph!" growled my father, mollified but sarcastic; "a pretty gentleman—a gentleman of sixteen!"

"It is true,"' I continued, without heeding the interruption, "that I lingered for a moment to read a placard by the way; but if you will take the trouble, sir, to inquire at the Rectory, you will find that I waited a quarter of an hour before I could send up your letter."

My father grinned and rubbed his hands. If there was one thing in the world that aggravated him more than another, it was to find his fire opposed to ice. Let him, however, succeed in igniting his adversary, and he was in a good humor directly.

"Come, come, Basil," said he, taking off his spectacles, "I never said you were not a good lad. Go to your books, boy—go to your books; and this evening I will examine you in vegetable physiology."

Silently, but not sullenly, I drew a chair to the table, and resumed my work. We were both satisfied, because each in his heart considered himself the victor. My father was amused at having irritated me, whereas I was content because he had, in some sort, withdrawn the expressions that annoyed me. Hence we both became good-tempered, and, according to our own tacit fashion, continued during the rest of that morning to be rather more than usually sociable.

Hours passed thus—hours of quiet study, during which the quick travelling of a pen or the occasional turning of a page alone disturbed the silence. The warm sunlight which shone in so greenly through the vine leaves, stole, inch by inch, round the broken vases in the garden beyond, and touched their brown mosses with a golden bloom. The patient shadow on the antique sundial wound its way imperceptibly from left to right, and long slanting threads of light and shadow pierced in time between the branches of the poplars. Our mornings were long, for we rose early and dined late; and while my father paid professional visits, I devoted my hours to study. It rarely happened that he could thus spend a whole day among his books. Just as the clock struck four, however, there came a ring at the bell.

My father settled himself obstinately in his chair.

"If that's a gratis patient," said he, between his teeth, "I'll not stir. From eight to ten are their hours, confound them!"

"If you please, sir," said Mary, peeping in, "if you please, sir, it's a gentleman."

"A stranger?" asked my father.

Mary nodded, put her hand to her mouth, and burst into an irrepressible giggle.

"If you please, sir," she began—but could get no farther.

My father was in a towering passion directly.

"Is the girl mad?" he shouted. "What is the meaning of this buffoonery?"

"Oh, sir—if you please, sir," ejaculated Mary, struggling with terror and laughter together, "it's the gentleman, sir. He—he says, if you please, sir, that his name is Almond Pudding!"

"Your pardon, Mademoiselle," said a plaintive voice. "Armand Proudhine—le Chevalier Armand Proudhine, at your service."

Mary disappeared with her apron to her mouth, and subsided into distant peals of laughter, leaving the Chevalier standing in the doorway.

He was a very little man, with a pinched and melancholy countenance, and an eye as wistful as a dog's. His threadbare clothes, made in the fashion of a dozen years before, had been decently mended in many places. A paste pin in a faded cravat, and a jaunty cane with a pinchbeck top, betrayed that he was still somewhat of a beau. His scant gray hair was tied behind with a piece of black ribbon, and he carried his hat under his arm, after the fashion of Elliston and the Prince Regent, as one sees them in the colored prints of fifty years ago.

He advanced a step, bowed, and laid his card upon the table.

"I believe," he said in his plaintive voice, and imperfect English, "that I have the honor to introduce myself to Monsieur Arbuthnot."

"If you want me, sir," said my father, gruffly, "I am Doctor Arbuthnot."

"And I, Monsieur," said the little Frenchman, laying his hand upon his heart, and bowing again—"I am the Wizard of the Caucasus."

"The what?" exclaimed my father.

"The Wizard of the Caucasus," replied our visitor, impressively.

There was an awkward pause, during which my father looked at me and touched his forehead significantly with his forefinger; while the Chevalier, embarrassed between his natural timidity and his desire to appear of importance, glanced from one face to the other, and waited for a reply. I hastened to disentangle the situation.

"I think I can explain this gentleman's meaning," I said. "Monsieur le Chevalier will perform to-morrow evening in the large room of the Red Lion Hotel. He is a professor of legerdemain."

"Of the marvellous art of legerdemain, Monsieur Arbuthnot," interrupted the Chevalier eagerly. "Prestidigitateur to the Court of Sachsenhausen, and successor to Al Hakim, the wise. It is I, Monsieur, that have invent the famous tour du pistolet; it is I, that have originate the great and surprising deception of the bottle; it is I whom the world does surname the Wizard of the Caucasus. Me voici!"

Carried away by the force of his own eloquence, the Chevalier fell into an attitude at the conclusion of his little speech; but remembering where he was, blushed, and bowed again.

"Pshaw," said my father impatiently, "the man's a conjuror."

The little Frenchman did not hear him. He was at that moment untying a packet which he carried in his hat, the contents whereof appeared to consist of a number of very small pink and yellow cards. Selecting a couple of each color, he deposited his hat carefully upon the floor and came a few steps nearer to the table.

"Monsieur will give me the hope to see him, with Monsieur son fils, at my Soirée Fantastique, n'est-ce pas?" he asked, timidly.

"Sir," said my father shortly, "I never encourage peripatetic mendicity."

The little Frenchman looked puzzled.

"Comment?" said he, and glanced to me for an explanation.

"I am very sorry, Monsieur," I interposed hastily; "but my father objects to public entertainments."

"Ah, mon Dieu! but not to this," cried the Chevalier, raising his hands and eyes in deprecating astonishment. "Not to my Soirée Fantastique! The art of legerdemain, Monsieur, is not immoral. He is graceful—he is surprising—he is innocent; and, Monsieur, he is patronized by the Church; he is patronized by your amiable Curé, Monsieur le Docteur Brand."

"Oh, father," I exclaimed, "Dr. Brand has taken tickets!"

"And pray, sir, what's that to me?" growled my father, without looking up from the book which he had ungraciously resumed. "Let Dr. Brand make a fool of himself, if he pleases. I'm not bound to do the same."

The Chevalier blushed crimson—not with humility this time, but with pride. He gathered the cards into his pocket, took up his hat, and saying stiffly—"Monsieur, je vous demande pardon."—moved towards the door.

On the threshold he paused, and turning towards me with an air of faded dignity:—"Young gentleman," he said, "you I thank for your politeness."

He seemed as if he would have said more—hesitated—became suddenly livid—put his hand to his head, and leaned for support against the wall.

My father was up and beside him in an instant. We carried rather than led him to the sofa, untied his cravat, and administered the necessary restoratives. He was all but insensible for some moments. Then the color came back to his lips, and he sighed heavily.

"An attack of the nerves," he said, shaking his head feebly. "An attack of the nerves, Messieurs."

My father looked doubtful.

"Are you often taken in this way?" he asked, with unusual gentleness.

"Mais oui, Monsieur," admitted the Frenchman, reluctantly. "He does often arrive to me. Not—not that he is dangerous. Ah, bah! Pas du tout!"

"Humph!" ejaculated my father, more doubtfully than before. "Let me feel your pulse."

The Chevalier bowed and submitted, watching the countenance of the operator all the time with an anxiety that was not lost upon me.

"Do you sleep well?" asked my father, holding the fragile little wrist between his finger and thumb.

"Passably, Monsieur."

"Dream much?"

"Ye—es, I dream."

"Are you subject to giddiness?"

The Chevalier shrugged his shoulders and looked uneasy.

"C'est vrai" he acknowledged, more unwillingly than ever, "J'ai des vertiges."

My father relinquished his hold and scribbled a rapid prescription.

"There, sir," said he, "get that preparation made up, and when you next feel as you felt just now, drink a wine-glassful. I should recommend you to keep some always at hand, in case of emergency. You will find further directions on the other side."

The little Frenchman attempted to get up with his usual vivacity; but was obliged to balance himself against the back of a chair.

"Monsieur," said he, with another of his profound bows, "I thank you infinitely. You make me too much attention; but I am grateful. And, Monsieur, my little girl—my child that is far away across the sea—she thanks you also. Elle m'aime, Monsieur—elle m'aime, cette pauvre petite! What shall she do if I die?"

Again he raised his hand to his brow. He was unconscious of anything theatrical in the gesture. He was in sad earnest, and his eyes were wet with tears, which he made no effort to conceal.

My father shuffled restlessly in his chair.

"No obligation—no obligation at all," he muttered, with a touch of impatience in his voice. "And now, what about those tickets? I suppose, Basil, you're dying to see all this tomfoolery?"

"That I am, sir," said I, joyfully. "I should like it above all things!"

The Chevalier glided forward, and laid a couple of little pink cards upon my father's desk.

"If," said he, timidly, "if Monsieur will make me the honor to accept...."

"Not for the world, sir—not for the world!" interposed my father. "The boy shan't go, unless I pay for the tickets."

"But, Monsieur...."

"Nothing of the kind, sir. I cannot hear of it. What are the prices of the seats?"

Our little visitor looked down and was silent; but I replied for him.

"The reserved seats," I whispered, "are half-a-crown each."

"Then I will take eight reserved," said my father, opening a drawer in his desk and bringing out a bright, new sovereign.

The little Frenchman started. He could hardly believe in such munificence.

"When? How much?" stammered he, with a pleasant confusion of adverbs.

"Eight," growled my father, scarcely able to repress a smile.

"Eight? mon Dieu, Monsieur, how you are generous! I shall keep for you all the first row."

"Oblige me by doing nothing of the kind," said my father, very decisively. "It would displease me extremely."

The Chevalier counted out the eight little pink cards, and ranged them in a row beside my father's desk.

"Count them, Monsieur, if you please," said he, his eyes wandering involuntarily towards the sovereign.

My father did so with much gravity, and handed over the money.

The Chevalier consigned it, with trembling fingers, to a small canvas bag, which looked very empty, and which came from the deepest recesses of his pocket.

"Monsieur," said he, "my thanks are in my heart. I will not fatigue you with them. Good-morning."

He bowed again, for perhaps the twentieth time; lingered a moment at the threshold; and then retired, closing the door softly after him.

My father rubbbed his head all over, and gave a great yawn of satisfaction.

"I am so much obliged to you, sir," I said, eagerly.

"What for?"

"For having bought those tickets. It was very kind of you."

"Hold your tongue. I hate to be thanked," snarled he, and plunged back again into his books and papers.

Once more the studious silence in the room—once more the rustling leaf and scratching pen, which only made the stillness seem more still, within and without.

"I beg your pardons," murmured the voice of the little Chevalier.

I turned, and saw him peeping through the half-open door. He looked more wistful than ever, and twisted the handle nervously between his fingers.

My father frowned, and muttered something between his teeth. I fear it was not very complimentary to the Chevalier.

"One word, Monsieur," pleaded the little man, edging himself round the door, "one small word!"

"Say it, sir, and have done with it," said my father, savagely.

The Chevalier hesitated.

"I—I—Monsieur le Docteur—that is, I wish...."

"Confound it, sir, what do you wish?"

The Chevalier brushed away a tear.

"Dites-moi," he said with suppressed agitation. "One word—yes or no—is he dangerous?"

My father's countenance softened.

"My good friend," he said, gently, "we are none of us safe for even a day, or an hour; but after all, that which we call danger is merely a relative position. I have known men in a state more precarious than yours who lived to a long old age, and I see no reason to doubt that with good living, good spirits, and precaution, you stand as fair a chance as another."

The little Frenchman pressed his hands together in token of gratitude, whispered a broken word or two of thanks, and bowed himself out of the room.

When he was fairly gone, my father flung a book at my head, and said, with more brevity than politeness:—

"Boy, bolt the door."

CHAPTER III.

THE EVENTS OF AN EVENING.

––––––––

"BASIL, MY BOY, IF YOU are going to that place, you must take Collins with you."

"Won't you go yourself, father?"

"I! Is the boy mad!"

"I hope not, sir; only as you took eight reserved seats, I thought...."

"You've no business to think, sir! Seven of those tickets are in the fire."

"For fear, then, you should fancy to burn the eighth, I'll wish you good-evening!"

So away I darted, called to Collins to follow me, and set off at a brisk pace towards the Red Lion Hotel. Collins was our indoor servant; a sharp, merry fellow, some ten years older than myself, who desired no better employment than to escort me upon such an occasion as the present. The audience had begun to assemble when we arrived. Collins went into the shilling places, while I ensconced myself in the second row of reserved seats. I had an excellent view of the stage. There, in the middle of the platform, stood the conjuror's table—a quaint, cabalistic-looking piece of furniture with carved black legs and a deep bordering of green cloth all round the top. A gay pagoda-shaped canopy of many hues was erected overhead. A long white wand leaned up against the wall. To the right stood a bench laden with mysterious jars, glittering bowls, gilded cones, mystical globes, colored glass boxes, and other properties. To the left stood a large arm-chair covered with crimson cloth. All this was very exciting, and I waited breathlessly till the Wizard should appear.

He came at last; but not, surely, our dapper little visitor of yesterday! A majestic beard of ashen gray fell in patriarchal locks almost to his knees. Upon his head he wore a high cap of some dark fur; upon his feet embroidered slippers; and round his waist a glittering belt patterned with hieroglyphics. A long woollen robe of chocolate and orange fell about him in heavy folds, and swept behind him, like a train. I could scarcely believe, at first, that it was the same person; but, when he spoke, despite the pomp and obscurity of his language. I recognised the plaintive voice of the little Chevalier.

"Messieurs et Mesdames," he began, and took up the wand to emphasize his discourse; "to read in the stars the events of the future—to transform into gold the metals inferior—to discover the composition of that Elixir who, by himself, would perpetuate life, was in past ages the aim and aspiration of the natural philosopher. But they are gone, those days—they are displaced, those sciences. The Alchemist and the Rosicrucian are no more, and of all their race, the professor of Legerdemain alone survives. Ladies and gentlemen, my magic he is simple. I retain not familiars. I employ not crucible, nor furnace, nor retort. I but amuse you with my agility of hand, and for commencement I tell you that you shall be deceived as well as the Wizard of the Caucasus can deceive you."

His voice trembled, and the slender wand shivered in his hand. Was this nervousness? Or was he, in accordance with the quaintness of his costume and the amplitude of his beard, enacting the feebleness of age?

He advanced to the front of the platform. "Three things I require," he said. "A watch, a pocket-handkerchief and a hat. Is there here among my visitors any person so gracious as to lend me these trifles? I will not injure them, ladies and gentlemen. I will only pound the watch in my mortar—burn the mouchoir in my lamp, and make a pudding in the chapeau. And, with all this, I engage to return them to their proprietors, better as new."

There was a pause, and a laugh. Presently a gentleman volunteered his hat, and a lady her embroidered handkerchief; but no person seemed willing to submit his watch to the pounding process.

"Shall nobody lend me the watch?" asked the Chevalier; but in a voice so hoarse that I scarcely recognised it.

A sudden thought struck me, and I rose in my place.

"I shall be happy to do so," I said aloud, and made my way round to the front of the platform.

At the moment when he took it from me, I spoke to him.

"Monsieur Proudhine," I whispered, "you are ill! What can I do for you?"

"Nothing, mon enfant," he answered, in the same low tone. "I suffer; mais il faut se résigner."

"Break off the performance—retire for half an hour."

"Impossible. See, they already observe us!"

And he drew back abruptly. There was a seat vacant in the front row. I took it, resolved at all events to watch him narrowly.

Not to detail too minutely the events of a performance which since that time has become sufficiently familiar, I may say that he carried out his programme with dreadful exactness, and, after appearing to burn the handkerchief to ashes and mix up a quantity of eggs and flour in the hat, proceeded very coolly to smash the works of my watch beneath his ponderous pestle. Notwithstanding my faith, I began to feel seriously uncomfortable. It was a neat little silver watch of foreign workmanship—not very valuable, to be sure, but precious to me as the most precious of repeaters.

"He is very tough, your watch, Monsieur," said the Wizard, pounding away vigorously. "He—he takes a long time ... Ah! mon Dieu!"

He raised his hand to his head, uttered a faint cry, and snatched at the back of the chair for support.

My first thought was that he had destroyed my watch by mistake—my second, that he was very ill indeed. Scarcely knowing what I did, and quite forgetting the audience, I jumped on the platform to his aid.

He shook his head, waved me away with one trembling hand, made a last effort to articulate, and fell heavily to the ground.

All was confusion in an instant. Everybody crowded to the stage; whilst I, with a presence of mind which afterwards surprised myself, made my way out by a side-door and ran to fetch my father. He was fortunately at home, and in less than ten minutes the Chevalier was under his care. We found him laid upon a sofa in one of the sitting-rooms of the inn, pale, rigid, insensible, and surrounded by an idle crowd of lookers-on. They had taken off his cap and beard, and the landlady was endeavoring to pour some brandy down his throat; but his teeth were fast set, and his lips were blue and cold.

"Oh, Doctor Arbuthnot! Doctor Arbuthnot!" cried a dozen voices at once, "the Conjuror is dying!"

"For which reason, I suppose, you are all trying to smother him!" said my father angrily. "Mistress Cobbe, I beg you will not trouble yourself to pour that brandy down the man's throat. He has no more power to swallow it than my stick. Basil, open the window, and help me to loosen these things about his throat. Good people, all, I must request you to leave the room. This man's life is in peril, and I can do nothing while you remain. Go home—go home. You will see no more conjuring to-night."

My father was peremptory, and the crowd unwillingly dispersed. One by one they left the room and gathered discontentedly in the passage. When it came to the last two or three, he took them by the shoulders, closed the door upon them, and turned the key.

Only the landlady, and elderly woman-servant, and myself remained.

The first thing my father did was to examine the pupil of the patient's eye, and lay his hand upon his heart. It still fluttered feebly, but the action of the lungs was suspended, and his hands and feet were cold as death.

My father shook his head.

"This man must be bled," said he, "but I have little hope of saving him."

He was bled, and, though still unconscious, became less rigid They then poured a little wine down his throat, and he fell into a passive but painless condition, more inanimate than sleep, but less positive than a state of trance.

A fire was then lighted, a mattress brought down, and the patient laid upon it, wrapped in many blankets. My father announced his intention of sitting up with him all night. In vain I begged for leave to share his vigil. He would hear of no such thing, but turned me out as he had turned out the others, bade me a brief "Good-night," and desired me to run home as quickly as I could.

At that stage of my history, to hear was to obey; so I took my way quietly through the bar of the hotel, and had just reached the door when a touch on my sleeve arrested me. It was Mr. Cobbe, the landlord—a portly, red-whiskered Boniface of the old English type.

"Good-evening, Mr. Basil," said he. "Going home, sir?"

"Yes, Mr. Cobbe," I replied. "I can be of no further use here."

"Well, sir, you've been of more use this evening than anybody—let alone the Doctor—that I must say for you," observed Mr. Cobbe, approvingly. "I never see such presence o' mind in so young a gen'leman before. Never, sir. Have a glass of grog and a cigar, sir, before you turn out."

Much as I felt flattered by the supposition that I smoked (which was more than I could have done to save my life), I declined Mr. Cobbe's obliging offer and wished him good-night. But the landlord of the Red Lion was in a gossiping humor, and would not let me go.

"If you won't take spirits, Mr. Basil," said he, "you must have a glass of negus. I couldn't let you go out without something warm—particular after the excitement you've gone through. Why, bless you, sir, when they ran out and told me, I shook like a leaf—and I don't look like a very nervous subject, do I? And so sudden as it was, too, poor little gentleman!"

"Very sudden, indeed," I replied, mechanically.

"Does Doctor Arbuthnot think he'll get the better of it, Mr. Basil?"

"I fear he has little hope."

Mr. Cobbe sighed, and shook his head, and smoked in silence.

"To be struck down just when he was playing such tricks as them conjuring dodges, do seem uncommon awful," said he, after a time. "What was he after at the minute?—making a pudding, wasn't he, in some gentleman's hat?"

I uttered a sudden ejaculation, and set down my glass of negus untasted. Till that moment I had not once thought of my watch.

"Oh, Mr. Cobbe!" I cried, "he was pounding my watch in the mortar!"

"Your watch, Mr. Basil?"

"Yes, mine—and I have not seen it since. What can have become of it? What shall I do?"

"Do!" echoed the landlord, seizing a candle; "why, go and look for it, to be sure, Mr. Basil. That's safe enough, you may be sure!"

I followed him to the room where the performance had taken place. It showed darkly and drearily by the light of one feeble candle. The benches and chairs were all in disorder. The wand lay where it had fallen from the hand of the Wizard. The mortar still stood on the table, with the pestle beside it. It contained only some fragments of broken glass.

Mr. Cobbe laughed triumphantly.

"Come, sir," said he, "the watch is safe enough, anyhow. Mounseer only made believe to pound it up, and now all that concerns us is to find it."

That was indeed all—not only all, but too much. We searched everything. We looked in all the jars and under all the moveables. We took the cover off the chair; we cleared the table; but without success. My watch had totally disappeared, and we at length decided that it must be concealed about the conjuror's person. Mr. Cobbe was my consoling angel.

"Bless you, sir," said he, "don't never be cast down. My wife shall look for the watch to-morrow morning, and I'll promise you we'll find out every pocket he has about him."

"And my father—you won't tell my father?" I said, dolefully.

Mr. Cobbe replied by a mute but expressive piece of pantomime and took me back to the bar, where the good landlady ratified all that her husband had promised in her name.

The stars shone brightly as I went home, and there was no moon. The town was intensely silent, and the road intensely solitary. I met no one on my way; let myself quietly in, and stole up to my bed-room in the dark.

It was already late; but I was restless and weary—too restless to sleep, and too weary to read. I could not detach myself from the impressions of the day; and I longed for the morning, that I might learn the fate of my watch, and the condition of the Chevalier.

At length, after some hours of wakefulness, I dropped into a profound and dreamless sleep.

CHAPTER IV.

THE CHEVALIER MAKES HIS LAST EXIT.

––––––––

All the world's a stage,

And all the men and women merely players:

They have their exits and their entrances.

As You Like It.

––––––––

I WAS WAKED BY MY FATHER's voice calling to me from the garden, and so started up with that strange and sudden sense of trouble which most of us have experienced at some time or other in our lives.

"Nine o'clock, Basil," cried my father. "Nine o'clock—come down directly, sir!"

I sprang out of bed, and for some seconds could remember nothing of what had happened; but when I looked out of the window and saw my father in his dressing-gown and slippers walking up and down the sunny path with his hands behind his back and his eyes fixed on the ground, it all flashed suddenly upon me. To plunge into my bath, dress, run down, and join him in the garden, was the work of but a few minutes.

"Good-morning, sir," I said, breathlessly.

He stopped short in his walk, and looked at me from head to foot.

"Humph!" said he, "you have dressed quickly...."

"Yes, sir; I was startled to find myself so late."

"So quickly," he continued, "that you have forgotten your watch."

I felt my face burn. I had not a word to answer.

"I suppose," said he, "you thought I should not find it out?"

"I had hoped to recover it first," I replied, falteringly; "but...."

"But you may make up your mind to the loss of it, sir; and serve you rightly, too," interposed my father. "I can tell you, for your satisfaction, that the man's clothes have been thoroughly examined, and that your watch has not been found. No doubt it lay somewhere on the table, and was stolen in the confusion."

I hung my head. I could have wept for vexation.

My father laughed sardonically.

"Well, Master Basil," he said, "the loss is yours, and yours only. You won't get another watch from me, I promise you."

I retorted angrily, whereat he only laughed the more; and then we went in to breakfast.

Our morning meal was more unsociable than usual. I was too much annoyed to speak, and my father too preoccupied. I longed to inquire after the Chevalier, but not choosing to break the silence, hurried through my breakfast that I might run round to the Red Lion immediately after. Before we had left the table, a messenger came to say that "the conjuror was taken worse," and so my father and I hastened away together.

He had passed from his trance-like sleep into a state of delirium, and when we entered the room was sitting up, pale and ghost-like, muttering to himself, and gesticulating as if in the presence of an audience.

"Pas du tout," said he fantastically, "pas du tout, Messieurs—here is no deception. You shall see him pass from my hand to the coffre, and yet you shall not find how he does travel."

My father smiled bitterly.

"Conjurer to the last!" said he. "In the face of death, what a mockery is his trade!"

Wandering as were his wits, he caught the last word and turned fiercely round; but there was no recognition in his eye.

"Trade, Monsieur!" he echoed. "Trade!—you shall not call him trade! Do you know who I am, that you dare call him trade? Dieu des Dieux! N'est-ce pas que je suis noble, moi? Trade!—when did one of my race embrace a trade? Canaille! I do condescend for my reasons to take your money, but you shall not call him a trade!"

Exhausted by this sudden burst of passion, he fell back upon his pillow, muttering and flushed. I bent over him, and caught a scattered phrase from time to time. He was dreaming of wealth, fancying himself rich and powerful, poor wretch! and all unconscious of his condition.

"You shall see my Chateaux," he said, "my horses—my carriages. Listen—it is the ringing of the bells. Aha! le jour viendra—le jour viendra! Conjuror! who speaks of a conjuror? I never was a conjuror! I deny it: and he lies who says it! Attendons! Is the curtain up? Ah! my table—where is my table? I cannot play till I have my table. Scélérats! je suis volé! je l'ai perdu! je l'ai perdu