7,19 €

Mehr erfahren.

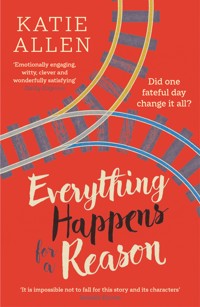

- Herausgeber: Orenda Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

When Rachel's baby is stillborn, she becomes obsessed with the idea that saving a stranger's life months earlier is to blame. An unforgettable, heart-wrenching, warm and funny debut… 'Emotionally engaging, witty, clever and wonderfully satisfying' Daily Express 'A stunning debut … a wise, moving, and thought-provoking novel' Susan Elliot Wright, author of The Flight of Cornelia Blackwood 'A heartbreaking, deeply moving and wonderfully witty tale, which celebrates all it means to be human' Isabelle Broom, author of The Getaway –––––––––––––– Mum-to-be Rachel did everything right, but it all went wrong. Her son, Luke, was stillborn and she finds herself on maternity leave without a baby, trying to make sense of her loss. When a misguided well-wisher tells her that "everything happens for a reason", she becomes obsessed with finding that reason, driven by grief and convinced that she is somehow to blame. She remembers that on the day she discovered her pregnancy, she'd stopped a man from jumping in front of a train, and she's now certain that saving his life cost her the life of her son. Desperate to find him, she enlists an unlikely ally in Lola, an Underground worker, and Lola's seven-year-old daughter, Josephine, and eventually tracks him down, with completely unexpected results... Both a heart-wrenchingly poignant portrait of grief and a gloriously uplifting and disarmingly funny story of a young woman's determination, Everything Happens for a Reason is a bittersweet, life- affirming read and, quite simply, unforgettable. –––––––––––––– 'A beautiful novel, bursting with raw emotional honesty and authenticity' Gill Paul, author of The Secret Wife 'So affecting. Profoundly sad. Funny. I just loved it' Louise Beech, author of This Is How We Are Human 'Darkly funny, yet poignant and moving ... Rachel's quest to find out if everything happens for a reason is both heartbreaking and heartwarming' Anna Bell, author of In Case You Missed It 'Some books teach you, others touch your soul, then there are books like this one that bury deep and create a home in your heart' Emma-Claire Wilson, Glass House Magazine 'A triumph … a book of hope and ambition and making sense of the world, a tale of acting spontaneously, living in the moment and throwing caution to the wind' Isabella May, author of Oh! What a Pavlova 'An incredibly important and beautifully written book. Bittersweet and brave, it will keep you both laughing and crying until the last page' Kate Ford, actress, Coronation Street 'The perfect mix of clever, funny and intensely moving' Cari Rosen, author of Secret Diary of a New Mum Aged 43 ¼ 'A heart-wrenching, soul-lifting read about loss and redemption in unlikely places' Eve Smith, author of The Waiting Rooms 'Read it and weep but also, incredibly, find moments to laugh and to know there is life after death' Julia Hobsbawm, author of The Simplicity Principle 'Simultaneously devastating and hilarious' Clare Allan, author of Poppy Shakespeare 'A memorable, poetic read ... The writing reminded me of Eleanor Oliphant' Becky Fleetwood, author of the Chroma series 'Quirky yet insightful, bright yet wistful, amusing yet emotional … full of contradictions that fuse into the most surprising, moving, and beautiful novel' LoveReading For fans of Jonas Jonasson, Matt Haig, Graeme Simsion and Rachel Joyce.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Seitenzahl: 470

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Ähnliche

Mum-to-be Rachel did everything right, but it all went wrong. Her son, Luke, was stillborn and she finds herself on maternity leave without a baby, trying to make sense of her loss.

When a misguided well-wisher tells her that ‘everything happens for a reason’, she becomes obsessed with finding that reason, driven by grief and convinced that she is somehow to blame. She remembers that on the day she discovered her pregnancy, she’d stopped a man from jumping in front of a train, and she’s now certain that saving his life cost her the life of her son.

Desperate to find him, she enlists an unlikely ally in Lola, an Underground worker, and Lola’s seven-year-old daughter, Josephine, and eventually tracks him down, with completely unexpected results…

Both a heart-wrenchingly poignant portrait of grief and a gloriously uplifting and disarmingly funny story of a young woman’s determination, Everything Happens for a Reason is a bittersweet, life-affirming read and, quite simply, unforgettable.

Everything Happens for a Reason

KATIE ALLEN

For Finn and all my family

Contents

Everything Happens for a Reason

I know what’s going to happen. You see it too. I’m colouring in too hard, over and over the same patch, and the paper’s falling apart.

I go round and round that day, the night, and the morning. I reach the end, go back to the start, do it four times, five, more. It takes hours, and sometimes minutes, depends what you include. I take different starting points – here, the taxi, the room – but I always go to the end. Sometimes a detail emerges, like that toddler pressing all the buttons in the lift and how we went down before we went up. It doesn’t help. I can’t make myself believe it, I don’t want to believe it. It doesn’t make sense.

They get that too. Everyone – well, not everyone. Most of them. They call (I don’t pick up), they text to say how bad they feel for me, how sorry, how awful it must be. You know, telling me what I should feel but at the same time careful to say they can’t imagine how I feel. All that energy poured into imagining something that they don’t want to be able to imagine or don’t want to tell me they can imagine or at least they imagine I don’t want them to imagine or to imagine them imagining. See? I’m going fucking mad here.

Sorry, inappropriate.

Hang on, the door’s about to go. Van’s stopping on the double yellows, it’ll be for me.

Sorry, gone longer than I meant.

If you’re reading these, you’ll be wondering what I’ve been up to. 2I have that effect on people. Will from Continuity called last week, asked, ‘What do you do all day?’ I told him laundry – which is true. No one tells you how helpful sadness is for staying on top of housework. I have a system: socks in one load, hang them in their pairs; T-shirts in another, iron while damp. It’s bad for the polar bears, but they’d understand. Two hours too late, I came up with a better line for Will. I’ll have it to hand next time: ‘All those little jobs I’ve been meaning to do for years.’ If pressed, I’ll say, ‘Gutters, the loft, sorting photos.’ They’ll know I’m busy and productive and everyone will be happy.

But because it’s you, I can tell you I haven’t started on the gutters (too wet). The loft is not something I can do on my own and the photos would set me back months – there are 10,543 and each photo costs me an average of four minutes’ preoccupation. (‘That row about that driver’; ‘Never again dungarees’; ‘Did we know that’s the happiest we’d ever be?’)

What do I do? The last few days have just gone. But I can’t say what with, apart from a socks and pants cycle.

I can tell you how it started though. With an invasion.

I was right, the florist van was for me. Jean and Tim, my mother’s friends. You don’t know them.

I was still behind the front door, picking out bits of rosemary added by some hipster florist, when the letterbox clattered open. He’s a light-footed creep, that postman.

To be fair, the post’s helpful. It gives the day shape. Washing machine on, coffee, post, empty machine, hang, iron. Routine’s important.

If you were into that kind of thing, you could use the post to measure how much time has passed. At the start, it was almost all cards. Now, nearly three weeks on – two weeks and five days – the cards are thinning out. We’re back to bills and bank statements. Except today, along with an insurance renewal for Lester and something from the taxman, sorry, tax person, there was a card. That’s what it looked like at least. I won’t bore you with what a Trojan horse 3is, but that’s what it was. Innocuous magnolia envelope, murderous contents.

I pieced together the Bristol postmark and the handwriting – biro, bulges on the a’s, b’s and d’s, like an elephant had sat on them. Liz.

Liz is on the you’ve-left-it-far-too-long list, along with cousin Jools, two women in Outreach and Vic from primary school.

I’m not unreasonable. I know some people were on holiday, or out of stamps. Some late arrivals managed to make it off the left-it-far-too-long list. But the deadline’s passed for the rest. Each day they stayed silent, they made you smaller.

I stare at Liz’s magnolia-clad appeal for clemency lying on the table. The kitchen table. I stopped to make coffee.

I should have known. Why expect maturity from someone who dots her i’s with a daisy.

You can tell I’m stalling. I might as well tell you. Explains the three-day silence. And like I said, no one likes a long silence.

I tear the envelope – easily, it’s cheap paper. Inside is a single postcard.

And this is the stupid bit, I pull it out without thinking. I drop it. It lands face up on the table, and it’s too late to look away. Its glassy little eyes stare up at me.

Who the fuck sends a picture of a newborn baby to a grieving mother?

Didn’t mean to leave you with that. He came in, with daffodils, and he doesn’t know about this. You know who. But I’m not going to give him that name. There’s no value in spelling this out – you of all people should see that. Let’s just call him E. 4

I’ve put him a chicken tikka in. I ate earlier. Routine.

People underestimate the power of structure. You watch them making up dinner on the fly or setting off without checking the trains, packing the day of a flight. Take Callum in Creativity, aka Mr Sorry-it’s-all-I’ve-got-in. Started with him serving up Bolognese with rice, then he’s eating cereal with apple juice and Sally walks out when he brings her a coffee with yoghurt stirred in. Next comes the mental breakdown and they think you need a Harley Street head doctor to work it out.

I’ve made a plan for us. It’s a simple one – two strands: I tell you what I’ve been up to, and I give you some pointers on what you should be up to. It’s amazing how many charts there are, targets, timelines, all sorts. Like now, for instance, you should be able to recognise me.

E’s gone to bed early. I’m waiting to take biscuits out of the oven, ginger and vanilla. No, not together. Two trays, one vanilla, one ginger, because I’m becoming someone who doesn’t know what they think or want.

The daffodils started it. ‘But they’re your favourites,’ says E.

‘Were.’

The ones outside our hospital window were early, mixed in with snowdrops. My mother says the same thing every year when they appear – ‘Start of new starts’ – and she brings out her three daffodil tea towels, puts away the primrose ones. Bluebells come next.

They’ll be gone by the time we go back for the post-mortem. 5

E called and said I have to remember to eat, so I went to the deli on the edge of the common, the one with rocky road.

It’s when I see the sign – the way they’ve made the U in Lou’s Beans look like a cup – that I feel it. Like being lighter, a sort of ease. If you want an image, there’s this advert for incontinence pads (nappies for grown-ups). A sixty-something woman running along a beach behind a Dalmatian like neither of them will ever tire.

For a minute, that’s what it was like. Because the last time I walked up that road, waited at that crossing and walked in to order a decaf skinny latte, you were with me. I knew where I was going and I would never tire.

I queued for a minute then left without ordering. The lightness had worn off. I can’t be there anymore, because nothing’s the same, is it? I could do that walk again and again, I could use that same non-biological washing powder and put on the same playlist – a mix of Mozart and Miles Davis compiled for your benefit – but any illusion of before will be just that. The walk’s all different anyway, the trees are full of white blossom. Can you see them?

Everything’s segmented by these moments that I’ll call before-and-after markers. The hospital is one. The markers fall, splay themselves out on your timeline like a body across a train track, and nothing is the same. There’s no crossing back over a marker. Or the only going back is the cruel kind, like this morning, a glimpse of before on a walk to a coffee shop.

And the markers bring on physical symptoms. Not just the avoidance tactics you’d expect: the deli, medical dramas, E. But symptoms inside me.

Take this one: I call it phrasal retentiveness. It’s like someone built a library in my head and I now store away every trite phrase, every 6text message, every ad slogan. (The incontinence one, by the way, is ‘laugh like everyone’s watching.’ Which comes from ‘dance like nobody’s watching’, which in my brain has turned into ‘load the dishwasher like nobody’s watching’, because there are upsides to being alone.)

It’s all exacerbated by the fact that in the after, everyone only ever speaks to me in old borrowed phrases, scared to improvise. It’s all ‘deepest sympathy’, ‘thoughts and prayers’ and ‘anything you need’.

I hear them once and they are there forever, stuck on repeat and word perfect. Sounds useful, doesn’t it? No doubt a career in the intelligence services beckons. But for now, the phrases are all I have for company and they’re crap at it.

You need examples, don’t you?

We’ll start with Bristol Liz. Yes, the glassy-eyed little creature on the card was hers. Did she even tell me she was pregnant?

Once I was breathing again, I turned his face away. On the other side, she and Tom were delighted to announce the arrival of their predictably named little boy, Max. Italics proclaimed ‘our little family has gotten [sic] eight pounds heavier’. She’d had them sent from home.

At the foot of the card, the elated new mother had managed to scrawl Hey, Hope you’re well, Liz xxx.

Hope you’re well. Really? How do you think I am? Never better, so well I’m running a marathon in memory of basic fucking manners.

To be fair, Liz almost certainly does hope I’m well. Everyone does. Not because they particularly care, they just want life to resume, or never to be disrupted in the first place. In the world of baby showers and families putting on eight pounds, there’s no place for our story.

Stupid phrasal retentiveness. ‘Hey, hope you’re well’ is unstoppable. Sometimes I hear it in her transatlantic squawk, sometimes in my voice and sometimes in the Bristol accent of a gentrified cider farmer drawing out the you’rrre.

This is how it will be now. Haunted by other people’s clumsy 7words. Liz’s ‘hey, hope you’re well’ and the likes of ‘when will you try again?’ and ‘at least he didn’t suffer.’ Sorry, you didn’t need to hear that one.

E’s going to be late, ‘lots to catch up on’. Catch up from what? He never stopped working. Bad timing, big campaign, he said. Shouty Americans keep calling in the middle of our night. He puts them on speakerphone to make me laugh. It’s all ‘sunset the old branding’, ‘hit kids hard with this’, ‘those drones won’t launch themselves’.

He’ll stay late, go on for a quick drink, then another. ‘Come and join us,’ he said on the phone.

‘They don’t want me in the way,’ I said.

‘They’d love to see you.’

‘Another time,’ I said. ‘Don’t rush back. It’ll do you good.’

Don’t blame yourself, he was like this before, says it’s part of the job, ‘the industry’. You’re the excuse to take it to extremes. The excuse he can’t talk about. And if he were here, what would I say to him? After what I did to us.

I was left with the consolation of ironed pyjamas and toast without crusts in front of the TV (sound mostly off for fear of the phrases). That was the plan. But because she always senses these moments, my mother calls.

I ignore her first two attempts and give in on the third.

‘Napping? It’s Tuesday. Come to prayer night,’ she says.

She deploys her usual lines: ‘It’s just what you need, Pebble’, ‘a place to reflect’, ‘friendly faces’.

I picture the friendly faces as medical students gathering round a bed to gawp at me, their worst car-crash victim yet. Their heads tip 8to one side, they try to smile but can’t mask their inner ‘Oh, shit! You’re a mess.’

But it’s intriguing – more so than The One Show, which let itself down last night by dedicating a full ten minutes to the prospect of snow disrupting Pancake Day. Plus, it’s a chance to meet Emma and Graham – the prayer-group leaders described as ‘like family’ by my mother – and all the other names that have come to dominate her Sunday lunchtime ramblings. The hotchpotch of lonely Londoners who took her in after my father’s latest affair.

I have the urge to refer to her as Grandma. Hope that’s OK.

Well, your grandma can’t believe it when I say, ‘You’re right. I’ll come.’

She’s overflowing with travel information and directions, as if her prayer group is an Al Qaeda cell that meets in a disused sewer works. As it turns out, they use a primary school in Elephant and Castle. It’s reachable by no fewer than seven different bus routes, an Overground station and the Northern Line, raves Grandma. ‘Emma and Graham are all about equal accession,’ she says. I let it go. Maybe it was intentional.

What do people wear to prayer nights?

Should never have left the house. Never have taken the Tube. New phrase: ‘Everything happens for a reason.’ 9

Why say that? E’s still out. I’m taking something. Will explain in morning, if I can.

Wed 22/2, 10:46

SUBJECT: Prayer night, or Some People Are Always Waiting to Pounce

I suppose Elephant and Castle sounds magical to you. It’s not. No elephants, no castles. But Grandma was right about the transport links.

She’d wanted to meet outside for a ‘quick pre-chat’ and go in together. I declined by reminding her of the local crime rate – helpful thing about Grandma is she scares easily.

Instead, I arrive late and find them singing in a circle, about fifteen of them. The man with the guitar has to be Graham but he looks nothing like his name. You’re picturing a silver-haired school bus driver, bit of a belly, aren’t you? Not this Graham. He’s in his thirties, slim, neat beard and a voice wasted on hallelujahs. Next to him is a tall Asian woman, singing louder than the rest, hands raised to the low classroom ceiling. Emma, no doubt. She’s wearing a green wrap-over cardigan, obscuring a baby bump. Thanks for the heads-up, Grandma.

The door’s closing behind me and I reach back for the handle but it bangs shut. Sodding fire doors. Graham’s blue eyes look over and your darling Grandma gives Emma a broad smile, like a fox cub presenting its first kill. Sorry, unintended ginger joke.

Emma makes a big show of welcoming me and tells the group that 10‘Moira’s daughter’ is going through ‘dark times’. I’m glad I dressed in black. I’m commended for ‘reaching out’, like we’re in sodding Motown. She’d get on well with Liz.

At least Emma speaks with big arm gestures, allowing me to establish that the cardigan is simply an unflattering cut. Bought online, probably.

In keeping with our classroom surroundings – papier mâché volcanoes, a solar system arranged with no regard for scale – Emma divides us into three smaller groups. Our task: to discuss ‘healing love’. I am with Graham, a skinny woman with a gold necklace that says Deb, and an older man.

Grandma’s group join hands in a corner and mumble a prayer that no one seems to know with any confidence. As they stand, I notice she’s wearing trousers. They’re old-people trousers (loose, cream, folds down the front) but young for her – young to fit in with her new friends.

Our group keep their hands to themselves but sit far too close together on low desks. Because there was a Tesco Express on the way and they were on offer, I have a pack of ginger biscuits in my bag. As I pull them out, a woman in the next group looks over. Graham makes things worse. ‘How sweet. Are they vegan?’ he asks.

‘Of course,’ I reply, hoping they’re made with kitten milk and the eggs of trafficked chickens.

But he’s moved on and is telling us to go round the group and talk about how ‘God’s love’ has guided us out of some valley or other. As you’d expect, we say nothing and stare at the unopened biscuits on my lap. Their eyes wander to my clammy hands, then my you-know-what.

‘I can start us off,’ says Graham. ‘Some of you know about my old life.’

Don’t get your hopes up. He goes on to describe what any normal person would call casual drinking but, in Graham’s mind – with Emma’s help – has morphed into full-blown alcoholism. To Graham, 11God appeared not in a crack house, nor in a jail cell, but at the champagne bar of a Michelin-starred restaurant, in the form of Emma, a City lawyer. Or something like that. I spent half his account wondering when and how to open the biscuits.

The older man, Ian, has a more interesting problem: gambling. Slots mainly. Sometimes horses. And yes, God’s set him straight. Or so he claims.

When it’s Deb’s turn, we wait as she reuses the same tissue over and over, stopping and starting her story. ‘What I want to say, is that God was there, never left me,’ she blubs. I don’t know if this is the best or worst moment to open the biscuits.

‘I mean, after I lost Rupert,’ Deb carries on.

I reach for her hand. It has to be her child. Deb’s too young to lose a husband. Rupert was Deb’s baby. That’s why Grandma brought me here.

‘His face was the first thing I saw in the morning, the last at night,’ Deb goes on. No night-time visits? Not a newborn. I take back my hand. ‘At the end I moved him into my room, put him right by my bed, where I could reach through the wires, stroke his ears. He liked that.’ A rabbit. A fucking rabbit.

Don’t worry. When it came to my turn, I knew exactly what to say.

‘My baby died. My human baby. Three weeks ago. Luke.’

Deb and Ian try to smile, it’s all they can think to do. Graham’s face doesn’t move, he’s been pre-briefed by Grandma. ‘He’s safe now,’ Graham says. ‘God has a special place for him.’

‘Like Rupert,’ says Deb.

Graham squeezes Deb’s arm. ‘Like Rupert.’

‘Actually, the Bible’s not clear on that,’ says Ian. ‘It says nothing about heaven for animals.’

I offer Deb a clean tissue.

‘Like you say, Ian, it’s not clear,’ says Graham. ‘But it doesn’t say there isn’t a heaven for animals.’12

Ian leafs through the Bible on his lap, stops to read something out. ‘And children—’

Graham cuts him off. ‘He’s safe now. They both are.’

Before I can ask if you hadn’t been safe before, the big, happy circle reforms. More songs, hands in the air and closed eyes. You see what I’m surrounded with here? I tell them and they’re singing. Singing and dancing like children. Your own grandmother.

They’re all doing the same smile. It’s like a yoga class. All so sure of themselves and the way they’ve decided to live their lives.

I bet you’re smiling too, at all this chaos over here. You should be trying to by now, anyway.

Emma’s still getting her breath back when she closes the evening with a prayer. She’s asking God to help us accept ‘His plan’. She’s piling phrase upon phrase, and I don’t need to tell you what that means for me. The words seep into the cracks in my brain like when I spilled honey on the wicker lounger. And her prayer has chapters, patience for politicians, comfort for refugees, thanks for the spring. My chair scrapes the floor, Grandma grabs my wrist like I’m a toddler. I shake it free and whisper loud enough for all of them, ‘This was a stupid idea.’ Only Graham opens his eyes.

On the Tube home, ‘he’s safe now’ and ‘all in God’s plan’ play on a loop in my head. Trust the sodding God phrases to be all-powerful.

‘I’m sorry?’ says the man next to me. Older, tweed hat.

‘Ignore me,’ I say, and he does. There’s nothing unusual about chanting ‘all in God’s plan’ on the Northern Line.

The train stops and I realise my second mistake of the night. Going via Oval.

Of course our driver chooses to linger there. And while he’s going nowhere, I’m dragged nine months backwards, to the day I saved him. The same day it all started – depending on your view of things. I was on my way to lunch with E. I know it’s not the most hygienic of things to admit to, but I had the test with me, in my handbag. Every time I looked in, the two little stripes were a deeper pink. Like 13GCSE, A-level and uni results rolled into one. We’d aced it. You’d have my blonde hair, his blue eyes, but you wouldn’t need glasses. His height, my patience, his confidence. I knew you were a boy.

I have a cycle like a panda. We’d done the April test too early, tried another one in May. This time we’d promised each other we’d wait, but I knew that was the day to do it. I could always buy another if it was too soon. I had this plan to hide it under his napkin at the restaurant, surprise him.

I wasn’t supposed to be there. I’d taken the Bank train by mistake, realised in time, got off at Oval to wait for the next Charing Cross one. He was at the end of the platform, pacing in squeaky trainers. You’ve heard the story a hundred times since, it’s one of my best. People asked me to tell it at dinner parties and in the office (they won’t do that with our story). But what I really remember is a jumble, pieces missing.

It lasted two minutes, three at most.

He steps on the yellow line, back, over the line, back, to the edge, back. His coat flaps, the kind that catches in doors. Wrong for the weather.

He’s touching his face, mumbling. No one else has seen him, or at least that’s what they pretend. Train lights on the walls, the sound, the shaking, he’s about to go, I throw my arms around him, fall back. I cushion our landing, but his elbow smacks into the ground and he shouts something like ‘no’ or ‘ow’. It’s his only sound. He’s shivering, so am I, my arms around him. He smells of sweat, and something wet, mud. I loosen my arms as he sits up. His one hand clasps the bad elbow, the other hand covers his face, and whatever it looked like a minute ago, it’s gone from my mind. A man asks, ‘You alright, love?’ The doors close and the train leaves, without me and with him still here.

And there I am, at Oval again, and ‘God’s plan’ is chanting itself hoarse in my head.

When I surface at Clapham Common, I have a voicemail from 14Grandma, for whom God’s plan has yet to include learning to text. It begins with the usual admonishments. ‘Storming out! Those are my friends,’ she says.

‘He was my baby,’ I say over her message.

Her voice slows, I’m Pebble again, and she asks if I’ll give the group another try. Francis is howling in the background, a cry of solidarity for his human sibling. She shushes him and rambles on at me, ‘And think about what Emma said – God’s plan for you.’

I didn’t listen to the rest. I called back. ‘All planned? This? Taken away from me?’

That got her. ‘All I’m saying, Pebble…’ She pauses. ‘All Emma and Graham are saying, is everything happens for a reason.’

My mother keeps calling. I’ve switched off my phone, disconnected the landline. Turned the lights off for when she drives over.

Where to begin?

You could go big and ask about tsunamis, earthquakes, hurricanes. Or go medical: cancer, kids’ cancer, eczema. Or political: wars, child soldiers, Brexit.

I should set Graham and Emma an essay:

The Indian Ocean tsunami killed a quarter of a million people; more than one child an hour has died since the war in Syria began; my baby was taken before he could live. Using examples, explain how and why Everything Happens for a Reason.

And yet.

And yet.

Let’s say for a minute they were right. When it comes to you, to us. It would be worse if there were no reason.15

Slept an hour, up again. You get these guests – like E’s mother – who bring too much luggage, unpack into every available space and tell you what to buy in for their breakfasts (plural). That’s Everything Happens for a Reason. It’s on an open-ended stay and things will only resolve when one of us kills the other.

And the man from Oval’s here too. He’d been gone for months, there was no room for him. When I half close my eyes, he’s rolled up in a ball at the end of our bed, giant hands covering his face.

Everything Happens for a Reason and I stayed up into the small hours, like the first evening that any houseguest arrives, when the enthusiasm is still genuine and there are easy things to say.

We thrashed things out over the ginger biscuits, washed down with raspberry leaf tea left over from your last week here – an effective show of courage from my side.

EHFAR, as it shall be known from now on, turns out to be a foreign visitor. If pushed, I would say Germano-French: brutally direct, yet exasperatingly philosophical. No time for ‘the flight was fine, thank you’, instead it’s straight in with, ‘why do you act like I don’t exist?’, ‘you can’t resist me’, ‘you know what you did.’

It’s a sign of a weak mind, writing down your problems to ‘work them through’ – kind of thing Tina in Coaching recommends. But making a list was the only way to keep EHFAR from delivering all its blows at once. You don’t need to see it all but it was something like this: 16

The reason?

Glass of wine at lunchBlue cheese in salad dressingEDangerous motherImpending nuclear holocaustDisabledAnd yes, when we get the post-mortem we can definitively cross off the first, maybe the second and probably the last one. (For the record, I’d have kept you.) But even the edited menu is like that choice between a sheep’s foot and a kangaroo’s doo-dah. (Seriously, who books a honeymoon in the Australian Outback?)

I tried Googling Bible verses, philosophers, the words ‘any such thing as unexplained death’. Even worse, I put it to E as he was getting up.

‘Bollocks,’ he said, doing that thing where he reaches up to touch the ceiling. ‘Don’t listen to her. It’s just shit, that’s what it is.’ He offered to work from home.

‘I’m fine,’ I said. ‘I’ll get some sleep.’

They dropped EHFAR on me, they will have to disarm it.

I called my mother (sorry, the whole Grandma thing isn’t working for me) and got Graham’s number. I woke her, but she likes to feel needed.

When Graham texts straight back, I picture him as a religious meerkat, always on alert, miniature guitar on his back. He’d love to come over for coffee, he says. Is eight too early? (Happy people. Bet he jogs, too.) 17

Graham’s visit is messy.

The newsagent only stocks biscuits containing eggs and/or other animal parts. So I peel and chop some carrots, arranging them as a crucifix, then a sun. In the end, I manage to create a random pattern. Thank God we said eleven.

I move the more sweary of E’s ‘artworks’ and rearrange the contents of the recycling bin so the beer bottles are obscured by a copy of the Guardian – Graham seems like someone who helps clear the table.

What people wear shouldn’t matter, but it does. I lift down the box from the top of the wardrobe and find the pre-you jeans. The widest ones do up easily and the first top I try – dark green, high neck – works well with them. I brush my hair and I’m back to how I was, in the before. The last traces of your short life are leaving my body. The bleeding has slowed to a trickle.

It’s wrong. We can’t do this yet, or ever. I climb into bed and wrap myself around that long pillow we bought for you. I feel for your kicks.

But he’ll be here any minute. I pick myself up, wash my face and put the jeans back in their box. I stick with the maternity cords. At least that’s the plan. It’s only when I’m in the doorway, staring at Graham’s dog collar, and his eyes wander down to my bare thighs that I realise I missed a step.

‘Sorry, mishap,’ I say. ‘In the kitchen.’

I run upstairs while he parks his bike on the hall carpet.

When I return, he’s let himself into the lounge, Bible on his lap.

He gestures to the carrot sticks. ‘I didn’t realise you had an older one.’

‘I don’t.’ 18

We pray for you while the kettle boils. He says that you’re in God’s care now. He’s part vicar, part child-protection services. You’re safe, nothing can harm you.

‘I saved someone’s life,’ I interrupt.

He mumbles, ‘Amen.’

‘Last summer. Oval Tube. He was jumping, I grabbed him.’

His palm is sticky, I slide my hand free.

‘What happened to him?’ he says.

‘The Tube staff took over.’

‘What about you? Was there someone for you to talk to?’

‘They pushed me out the way. I couldn’t see him, his face. But it’s nothing really. You would have done the same.’ I retreat to the kitchen, asking, ‘Do you think everything happens for a reason? Someone said that to me.’ I linger by the sink, giving him time to get his answer right. When I return with the coffee, he has his Bible open.

‘Not what it says in there. I want to know what you think,’ I say.

He closes it before I can see the page. He pulls off his dog collar – it’s plastic and springy. ‘You can touch it if you want,’ he says.

I flex it, turn it over in my hands. I want to hold it up to my neck and look in the mirror.

‘Yes,’ he says. ‘Yes, I do think so. Everything happens for a reason.’

‘Then it’s a shitty system.’ I hand the dog collar back. ‘How do you explain that to Syrians? Or the tsunami people, abused children? What reason do you give them?’

He’s ready with an answer. ‘There are connections you cannot see. You’re being too earthly.’

In other words, it’s still my fault.19

I attached some photos for you, but removed them again.

Helen, the midwife, brought them round. They were on a memory stick, ‘so you only look at them when you’re ready,’ she said.

I tried changing them to black and white, to help with your fingernails and your lips, hide it a bit, you know, the blood. (One day, I’ll Google how that happened.) But black and white makes your lips black and that’s worse. It says on your charts that you should be looking at pictures now, three weeks. Black-and-white ones with lots of clear shapes work best. I bought you that Art for Baby book from the Louvre, on the babymoon – that’s what they call your last holiday without a baby, where you talk about how you won’t change and how things will be hard, but that because you know they will be hard it won’t matter, and that really, everything will be perfect.

The ones of your feet came out well. I’ve printed one, put it in my wallet. I keep looking at it, like that’s all I’ve lost, your feet. I saw someone posted that you can commission an artist to do a painting or a sketch, without the bruises and marks. Is that offensive? I’ll print another copy of your feet in black and white, and stick it in the back of the art book for you.

I’ve run away. I’m on a damp bench. I can’t go home – for the next three hours, at least.

Anca is there. It’s her day. Monday used to suit us. We’d tidy and clean on Sunday before we paid her to tidy and clean the next morning. 20

Last week and the one before, I convinced E to tell her not to come, and to tell her why, and to pay her anyway. She dropped a card through the door. Then I gave in and told him she could come back today.

I should have planned to go somewhere, get out before she came. But the truth is I haven’t left the house since prayer night. Who would? Well, I’m out now.

And she was early. She rang the bell and let herself in before I could answer. I was halfway down the stairs when I heard her key, bashed my shin fleeing back to the bedroom. She started on the kitchen, making herself a coffee, phone on loudspeaker to a friend or sister, the cutlery drawer opening and closing, barstools scraping on the tiles.

Of course it occurred to me that I should let her know I was in the house. It was either that or climb out a window – that also occurred to me. But the longer I sat on the edge of the bed, the harder I was stuck there. You can’t get away with ‘I didn’t hear you come in’ when the other person’s been hoovering your lounge. Instead, I opened a magazine, ready to look up and say, ‘oh hi, Anca’, and I listened. And do you know what I heard? Your wardrobe door, in YOUR room, with YOUR things. That unstuck me.

She looks round, your little blue hairbrush in one hand, bag of cotton wool in the other.

‘You don’t need to clean in here,’ I say.

Behind her, the other things from your changing table are on the wardrobe shelf. She’s putting you away.

I try again: ‘You don’t need to do this room.’

‘You’re not at work?’ she says.

‘Please, just leave this room.’

‘It’s OK. I’ll tidy it for you.’ She takes your grey cardigan off its hook on the wall, hangs it inside the wardrobe.

‘Please, it’s fine like this. I’ll do it, later. I’ve got nothing else to do,’ I say. 21

‘What about work?’

‘I’m off work.’ I need to explain. ‘I can stay off. I get the same leave, the same as if it hadn’t, you know.’

‘Work might be good. Get you out.’ She waves towards the window.

‘I go out,’ I say. It’s the longest conversation we’ve ever had. ‘I am out all the time, lots to sort out. And I might change job anyway, find something better for me.’

She closes the wardrobe door, picks up your art book, the black-and-white one, with your feet tucked inside the cover. ‘Shall I leave this?’

I grab the book. ‘Just leave everything. Don’t touch it. I want it like this.’

‘Okaaaayy.’ She puts her hands up. ‘I’ll do your room. Don’t walk in the kitchen, the floor’s wet.’

‘I’m going out anyway.’ I motion for her to leave your room first and close the door after us.

I can’t be in the house with her. I hate this, all these people telling me I’m messed up, too sad, lazy. Her meddling hands. Meddling hands, held up like a hostage, like I’m the dangerous one. Because that’s what they really think, all of them. That it’s my fault. It’s all my fault and I might as well get on and live with it.

I left a note and twenty pounds on top of her handbag in the kitchen. We don’t need you to come any more. Here’s some extra. Thanks.

Don’t worry, I’ll put your things back tonight. I’ve got the book safe. I should have told her to leave the key. I should text her. I need to walk. Walk and think only about walking.22

Back on my bench. Did I know this all along and hide it from myself, from you?

It was your book, black-and-white concertina people, all holding hands and touching toes, disappearing off the edges of the page. The last picture, called ‘All One’. I bet you worked it out ages ago – that’s how you see the world at this stage, all of us connected to one another, you and me, everyone. You’d love chains of paper people, I’ll make you some. And Graham saw it too – he wanted me to piece it together myself, the whole ‘connections you cannot see’ thing.

It goes back to then, last June. Your cells were going about their business, happily dividing, he was pacing on Oval platform, seconds from death, and I was the one who stopped him. He got to live and you…

He’s the reason, isn’t he? The only possible reason. The obvious reason. The EHFAR REASON.

It’s freezing. I should go home. But Anca’s still there. I can’t go home. No, not home. I know where I need to go.

I’m back. Anca left the key.

I need you to trust me when I promise you I’ll find him, make it all make sense. Are you in him? Is that too obvious? I’ve started, in the obvious place. Sorry, keep saying ‘obvious’, but that’s because it is. I’m so slow. This is what they call baby brain. Not blaming you. It is what it is. It all is. And most of it is obvious. 23

You wouldn’t believe how hard it is to find a human working at a Tube station. When the machines rise up, the London Underground will be their headquarters.

I looked around for a few minutes, waved at the CCTV, knocked on the ticket window. I hurt my hand banging on a thick metal door. The man who finally emerged from behind it was resigned to the imminent robot revolution.

‘What’s this say?’ he asks. His tea splashes as he gestures to the sign.

‘Staff only,’ I reply. ‘But I’m looking for someone.’

‘I’m busy,’ he says.

‘Doing what?’ I ask it out of genuine curiosity.

‘What’s it look like?’ He steps back. I’m about to lose him behind the sacred door.

‘I saved someone’s life,’ I say. ‘Here. Last year.’

That’s got him. I tell him I need to find someone who was working that day, 21st June.

‘Do I look like a walking logbook?’ He likes rhetorical questions.

I look at my shoes, chastised.

‘What day of the week was it?’ he says.

‘A Tuesday. Tuesday morning.’

‘Lola usually does Tuesdays,’ he says.

‘Do you think she’ll help me?’

‘Doesn’t mean she was on Tuesdays last year, does it?’ he says. It’s impossible to tell if he’s playing with me, or thick. ‘Try her. Southbound platform.’

He won’t let me through the barrier so I have to tap my card and pay again.

She’s not what you’d expect, nothing ever is. She’s older, short and what my grandma used to call ‘plump’. I watch her from a bench for three or four trains. Was she there that day?

The machine instructs people to ‘mind the gap’ and to ‘let customers off the train first’, but she adds a human touch, informing 24them it won’t be stopping at Tooting Bec or there’ll be another one in four minutes. Her accent is African, I’d say West African if pushed, probably Ghanaian. When there’s a lull, I approach. Her badge says ‘Omolola’.

‘I need to talk to you,’ I say. She looks around, like she’s checking who else can hear us.

‘Next train in six minutes. Driver shortage,’ she says.

‘It’s about something that happened last year, twenty-first of June, a Tuesday, you work Tuesdays.’

‘Sometimes.’

‘I need your help. Just two minutes.’

‘You should ask my manager,’ she says.

‘It has to be you.’

‘There’s a train coming, you have to wait.’ She waves towards the silent tunnel.

‘You said it was six minutes.’

‘If you are going to get abusive, I will report you.’ She puts her hand up to her radio.

‘I should be the one reporting you. You’re supposed to be here to help.’ It comes out cold; it’s the voice E has after a New York trip. He’s made me like this. You, it, meddling-hands-Anca. Everything has made me like this.

Omolola looks terrified. ‘Come back at twelve. My break.’ She walks away to a machine in the wall.

Only twenty minutes to kill. I go to the northbound platform and sit on the same bench as that day. There’s a woman in his spot. Is she going to try too? Is this where they all go? That happens with suicide, favourite places. She’s blocking my view of the edge. I move over to her and stand too close. She walks along the platform and I go back to my bench.

There was a murder case I read about once where they took the witness and the whole jury on a field trip to an industrial estate. They asked the witness, a woman who’d been jogging, to stand in the very 25same spot where she’d watched the murderer and the victim fighting, an alleyway between two factories, one made tyres, the other made ice-cream.

‘I need you to picture the scene,’ the prosecutor says to the witness. She closes her eyes and sucks in air thick with the scent of rubber. After three breaths, she opens her eyes and tells them how he ran towards a hedgerow, tripped on a kerb and went back on himself to drop the knife down a drain. They search the sewers and pull out the knife, still covered in DNA and fingerprints. He got twenty years, she got a new identity.

The smells on Oval northbound platform are nothing distinctive. That same canned Underground smell of metal grinding on metal, fried chicken and sweat. Still, I gulp it in, try to picture him. I focus on that spot, where we trembled together. I imagine peeling his hands away from his face, feeling the shape of his cheeks with my fingers.

Back on the southbound platform, Omolola is being very punctual about her break time and I have to run to catch her on the escalator. She stands on the left, but it’s quiet.

‘Last summer, in June, do you remember the man who tried to jump?’ I ask.

‘We get them a lot,’ she says.

‘But I saved this one. Grabbed him, pulled him back.’ We’re at the top of the escalator, she accelerates towards the staff-only door. ‘I need to find him,’ I say.

She shakes her arm free and taps her card to open the barriers. ‘I can’t help you,’ she says.

‘But everything happens for a reason.’

‘Not today,’ she replies.

I’ll try her again tomorrow.

One of those artists emailed back, they charge £650 and up. E’s good at drawing. 26

Didn’t work out. E’s fault.

It may surprise you to learn that he of all people is taking packed lunches to work. Don’t worry, not an economy drive. He’s on a Neanderthal diet. Nothing packaged, nothing processed. He says we need to look after ourselves. He wants to run home from work three times a week and he’s ordered a new bike for weekends. There’s a note stuck to the fridge asking me, COULD A CAVEMAN EAT IT?

It’s in a book he bought from a life coach at the office. ‘It’s something we can do together,’ he says, pointing at ‘recipes’ for raw broccoli with raisins. How am I supposed to have room for anything new?

‘And tell Anca we need to switch to bleach-free cleaning products,’ he says. ‘I’ll send you the link to order these organic ones. Tanya uses them.’

‘Who’s Tanya?’

‘You know her, Belgian, she was at the dinner at the Korean place. One of the grads. She’s on Sam’s team.’

‘Who’s Sam?’

He’s left the conversation, back to his phone, emailing Tanya about bamboo toilet brushes and edamame beans. My mother was right, handsome men make exhausting husbands. When I was little I thought she meant because of all the weightlifting and jousting they would have to do. Her choice of storybooks, and words, are responsible for all sorts of mess.

I haven’t told him about Anca. That I let her go.

E left me a lunchbox. Grilled chicken, boiled egg, lettuce leaves and seven walnuts. Either he wants to starve me back to a size ten or he thought supplying a meal would secure my help – he also left a shopping list. Presumably the cavemen were able to fly in their strawberries and avocados out of season, and their womenfolk spent their days making almond butter. 27

It was late morning by the time I’d tracked down all his items, filled the fridge and added my own note to the door in reply (YOU TELL ME). I left my lunchbox for him to eat at dinnertime. Repetition was doubtless the main characteristic of the cave people’s diets.

When I get to Oval, it’s Omolola’s break time so I have to bang on the steel door. The same man appears, a sandwich in one hand, free newspaper in the other. Name badge says ‘Vernon’.

‘You still can’t read?’ says Vernon.

‘I need to see Omolola.’

His mouth hangs open, there’s unchewed bread in his back teeth.

I try again: ‘Lola. Can you get her?’

‘Left early, hasn’t she?’

‘Of course,’ I say. ‘You should try the caveman diet.’

Tanya with the permanent tan was supposed to have moved to New York. But her Facebook says she came back to London at Christmas. Farcical caption under a selfie on that famous ice rink: ‘Back soon for another bite of the Big Red Apple.’ Red? It was never red. Now it’s circling in my head. Big Red Apple. She’s wearing a red beret. Her page is all selfies, taken from above to hide her double chin and eye bags. E will see that. She won’t age well.

March now. Our last month together is gone. 28

Didn’t I tell you to trust me? Lola – that’s what she prefers to be called – is brilliant. Got her on a bad day before. Here’s a piece of pound-shop wisdom for you: no one ever knows what’s truly going on in someone else’s life.

I have to go out again in a minute, but this is where we are.

I braved the end of the morning rush and caught her before any break times. It was that point in the morning when the suits were gone and it was all hairy men in suede trainers and thick-rimmed glasses, and women in long skirts with fluorescent ankle socks. I struggled through their rucksacks to Lola’s platform. She recognised me but seemed to think we were meeting by chance.

‘You still looking for the man?’ she asks.

‘I feel awful about before,’ I say. ‘I shouldn’t have asked you.’

‘Why you need to find him?’ Her voice is efficient, strong.

A train pulls in, and she speaks into her radio and waves a plastic paddle about. She’s not wearing a wedding ring – guessing it’s a health-and-safety thing. But then why would she be allowed hoop earrings? Why is anyone?

The train leaves, the platform clears.

‘It’s silly. You won’t get it,’ I say. ‘I’ll let you carry on.’

‘I remember him … and you,’ she says.

‘You all took over. I had him, on the ground, you pulled me off, pushed me away.’

‘You did a good thing,’ she says.

‘I need to find him.’

She strokes out the creases in her jumper. She needs the next size up.

‘But I know you’re not allowed to help me,’ I carry on. ‘It was silly, I shouldn’t have asked.’ The next train rumbles closer and I turn to leave. 29

‘You been looking for him this whole time?’ she asks.

‘I just started. I need to find him.’

‘Why?’

I wait while she does whatever it is she does. As the train leaves, I follow her eyes up to a CCTV camera.

‘I wasn’t supposed to be there,’ I say, and because her eyes are telling me she wants more, I tell her about you. How I was on my way to surprise E with the news. Her face shows she understands. But it’s not like with other mothers; I don’t resent her for it. Anyway, hers must be grown up. I’d guess she’s at least forty-five, had them young.

‘What did you have?’ she asks.

‘A boy. Luke.’

‘He’s at nursery?’ She’s looking at my empty arms.

I listen for a train, anything. You’d love nursery. You’re on a waiting list for one where they speak Mandarin.

There’s a bench along the platform. Lola sits next to me, asks, ‘What happened?’

‘He just stopped kicking.’

She squeezes my hand, leans closer. Her shoulder’s pillowy.

Your chart says your hearing is fully developed now. I wish you could hear Lola’s voice. It’s in my head. ‘You did a good thing. You did a good thing…’ It’s a cross between an airline pilot and a nurse, authority and comfort. She gets it. All those singing Christians, Bristol Liz and the time-will-healers have been belittling you, and don’t even start me on the ‘I had a miscarriage too’ walrus at the hairdressers. But Lola’s different.

I left her to her paddle waving and radioing, and waited by the barriers for her next break. After one of her colleagues asked if I was lost, I moved to the bus stop outside, glad of my new habit of wearing two jumpers under my coat (padding). I went back inside a few minutes before twelve. 30

Lola smiled, she looked relieved that I hadn’t fled.

‘I thought I could buy you lunch,’ I said.

She had thirty minutes but knew somewhere quick, she said. It was a kebab shop where she gets a discount. She ordered wraps with chips for both of us and I paid.

She’s different above ground. Her voice is louder and she laughs her words rather than speaking them. Her tight black curls bounce around when she talks.

It turns out she also has phrasal retentiveness.

‘You said everything happens for a reason,’ she says, as we find a table at the back.

‘I thought you weren’t listening,’ I say.

She gives me a teacher look.

‘He took Luke’s place. I need to know why,’ I say.

‘What would it change?’

‘I thought you got it. He’s out there living. What’s he doing with it?’

She checks her watch, tries to catch the kebab man’s eye. ‘What would make you feel better?’ she asks me.

It’s a stupid question, hurtful. My answer’s out before I can stop it. ‘I want my baby back.’

A plate clunks down in front of me, chips fall onto the tabletop. He’s slow to retreat.

‘I mean, say you find him, what would make you feel better?’ asks Lola. She pulls her phone from her pocket, checks the time on that and calls across to the waiter, ‘Put it in a takeaway box.’

‘I haven’t had a chance to think it through,’ I say. ‘But say it’s something like this.’ I find a pen and an old envelope in my bag. ‘Say he was a brain surgeon and since last June, he’s saved two people a week. That’s, roughly, seventy-eight lives. And what if half of those people he saved were social workers, police officers or fire fighters, and each of them has so far saved three more people. Now we’re up to one hundred and ninety-five lives. Or if you go back to the start, 31count him as well, you’re looking at one hundred and ninety-six lives saved. All because I was on that platform. All because of Luke and because everything happens for a reason.’

Her face concentrates hard as she adds it up with me. I finish out of breath, like the underdog in a courtroom drama. It’s unclear whether it’s my delivery or the sheer numbers, but she says she’ll help, she’ll get me the records for that day. She’s going to log in when the office is empty. We’re meeting at six. I said I’d buy her dinner.

How could I have been so stupid? And I pulled you along with me. I waited outside the station, where Lola said, for twenty minutes, and now I’ve retreated into the relative warmth of Sainsbury’s to watch for her through the window. (Writing this on my phone.)

It’s all stupid. Me, Lola, my plan, meeting here. Why would she help me? She just wanted me to go away. Should have worked it out from the meeting place – no one would ever ask anyone to try to find them outside Brixton Tube. The body smells are medieval. And there’s so much anger. I’m watching them now, two tides colliding. The commuters trudge out with headphones and hungry faces, and in barge the socialisers on their way into town – porn-star make-up, two drinks away from a fight. In the midst of it all, there’s a man gesticulating and shouting into a microphone about an indiscernible god. He’s so angry, it’s making a shield around him.

The security guard in here keeps looking at me – like I’m the type who’d nick their three-day-old carnations. At least I’m fitting in. Hang on, he’s saying something.32

We have a name. A first name AND a surname. Can you believe it? Ben Palmer. Ben Palmer of Kennington. Early Googling shows nothing obvious, but it’s so much to work with.

It’s all down to Lola, who continues to be full of surprises. She did make me panic for a bit there but turned up in the end, right after I was thrown out of Sainsbury’s. (Quite proud about that. I was ‘loitering’, apparently. And he called me ‘miss’, not ‘madam’.)

Thirty-five minutes past six and you know what she says? ‘Sorry I’m a bit late.’

I throw my arms around her – put it down to relief and cold combined, and she seems like a hugger.

‘You find him?’ I ask her, shaking the blood back into my fingers.

‘We need to go somewhere first.’ She’s walking.

I jog to catch up as she heads down the street. The pavement is one long bus stop, and she weaves between walking sticks and pushchairs. Where was her sense of urgency half an hour ago?

We turn into a quieter road. She’s faster than you’d expect. She stops at a metal gate and presses the buzzer on an intercom. There’s a click, and I follow her through the gate and then a door, propped ajar with a Dr Pepper can. We climb to the third floor, where a woman the same build as Lola is waiting in a doorway. Instead of curls she has long braids, but her face is just like Lola’s.

Lola doesn’t introduce me. The woman shouts back over her shoulder, ‘Josephine. Josephine!’

She and Lola speak in another language. It’s fast and loud. It seems the woman is also upset by Lola’s timekeeping. Behind her, a little girl appears. She’s in a maroon school sweatshirt. There are beads in her hair, and yellow paint. She sits on the floor and pulls her boots 33on. When she’s finished, she looks up with a proud smile, she has a dimple on one side, her eyes are deep brown and bright. She’s beautiful.

Lola says something to her.