Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Books on Demand

- Kategorie: Fantasy und Science-Fiction

- Sprache: Englisch

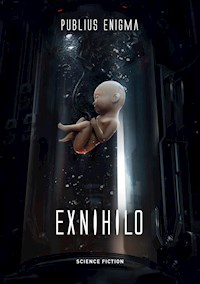

ELAI WALI HUMAN was never born. After the devastation of The Total War, there is no one left who can bear children. Humanity has destroyed itself and its home on Earth. Most of the world's population has been forced into exile in space, which has now become their home. The Interhumane Synedrion brought Elai to life in the year 2239. He was produced in a Moon-based fertility factory and, like all other artificially generated humans, he carries a terrible genetic flaw. A flaw which means average life expectancy is just 41 years. When a group of scientists pick up a mysterious signal from one of Jupiter's remotest moons, Elai is sent on a mission of discovery. Is the signal a sign of life? And how will the Interhumane Synedrion react to what Elai finds on Exnihilo?

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 663

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2022

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Contents

Love

Arrival

Briefing

Expedition

Transmission

Wreck

Doctor

Age

Resuscitation

Colonists

The Woman

The Synedrion

Oxygen

Deceased

Visio Studio

The Autopsy

The leak

Flight

Emergency exit

Trial

The Antenna

Way out

Loyalty

The Light

Death sentence

Water

Trust

Ocean City

The children

Voyaging out

Love

MARYON EMBRACED ISAAC. Her hand gripped the back of his neck and she kissed his silken soft lips passionately. She felt his hands on her body as they gently glided across her skin, over her back and down.

They were covered only by the thin sheet they had wrapped around them for warmth, but that was no longer a problem, and now the sheet began to flutter away from them. She caught it in the air and set off toward the window so that they twirled around and in rolling somersaults were wrapped up together again like a pupa. It felt right to be a little bit covered. Though no one could see them up here in their private quarters, it seemed as though the whole universe was watching from the other side of the window on Discover IV.

Naked bodies merging with each other in pure, weightless pleasure.

She saw Isaac’s face shining with its customary amiable expression and she responded with countless kisses and caresses. Though cryo-hibernation had temporarily robbed them of their hair, it hadn’t lessened the mutual attraction they felt for each other; in that moment their hearts were beating in perfect harmony. Like there was a higher meaning to this, a pact that would not only bind them for the rest of their lives but would also ensure their love would endure, even far into the future after they had long since passed away.

One hour later, Maryon floated into the common dining area where other crew members were variously suspended around the room. From the corner of her eye she caught sight of Isaac already eating.A deep joy still pulsed in her veins but she felt compelled to conceal it from the others. None of them knew about their relationship, in fact they weren’t supposed to have one. It was actually prohibited. One good thing, though, was that if they were discovered, no one could do anything about it. After hurtling through space for six years, they were already millions of kilometers away from Earth. Even though Maryon and Isaac were in breach of the contracts they had signed, which forbade any sort of partnership, there could no longer be any consequences. They couldn’t be sent back and their colleagues had no other options to punish them. Perhaps it was mostly for the sake of the others that they kept their relationship secret. Also, it had only been two days since they had woken from cryo-hibernation – there was something thrilling about having a secret.

“Have we heard anything from Earth?” she asked no one in particular.

Some of the crew shook their heads.

“We were just talking about it. Timmy thinks there might be something amiss with our receivers. Maybe a collision with something,” one of the astronauts said.

“Yeah, we should really have system alarms for that,” Timmy Milton, one of the ship’s engineers added, “but there could be a hundred reasons.”

The refrigerator in the canteen was filled with various kinds of longlife foodstuffs. Just as with the humans on board, ingredients and meals had been deep frozen and the system had thawed them out automatically. They were still edible even after so many years. Maryon took a dessert pouch and pierced it with a straw. It tasted sweet.

The crew were still talking:

“It’s just weird no alarms have been logged. There should be error reports if something happened but I’ve checked right back to 2163 and I can’t find a thing.”

“I’ve got the computers scanning for long-distance satellites. Maybe they can put us in touch with Earth somehow. On the other hand there may of course be obstacles in the way, meteor storms blocking the signals, solar winds, stuff like that – but it’s pretty unlikely. The most probable explanation is that something impacted the antennae.”

Dr. Sally Milton peered shrewdly and suggested:

“I can’t see any other option than someone going out there to investigate. What else can we do? Just hang around waiting until it resolves itself? It’s essential we contact Florida.”

Her remark was met with silence. It wasn’t exactly a job they were going to squabble over. Spacewalks were both difficult and risky.

“I’ll do it,” Maryon broke the silence and sucked up more of the thick sweet liquid dessert.

“Then there’s two of you,” the doctor smiled and glanced at Isaac, who Maryon suddenly realized was the other volunteer. If she had known she would never have proposed accompanying him.

The view reminded her of a giant darkroom curtain with tiny pinpricks through which light penetrated from the other side. This was her first spacewalk. The vast vault of the universe was beautiful and fascinating with its countless stars and galaxies, she had never experienced something so incredible. The silence and stillness of space dominated everything, interrupted only by the radio and small puffs of air expelled from their spacesuits. Maryon and Isaac floated slowly toward some large grey parabolic dishes perched on one of the long arms that protruded from the spacecraft.

Isaac coughed.

“Are you cold?”

“Maybe a little,” he answered and cleared his throat, “to tell the truth, I’ve been a bit off since we woke from cryo-hib.”

Were you also cold earlier in the room with me? Maryon wanted to ask but suppressed it. There were others listening on the radio.

“Isaac, you can regulate the temperature in your spacesuit,” a voice crackled inside their helmets. “Check beside the oxygen tank, there’s a button you can turn.”

“Thanks, I’ll try.”

“It’s quite usual to feel cold for a few days after hibernation,” the voice added but was interrupted by Isaac.

“We’re here. Let’s take a closer look at this.”

Maryon stopped abruptly and pulled a cord closer to her at the end of which was a toolbox.

They looked for the tell-tale evidence of damage from an asteroid fragment.

“No immediately observable scratches. Everything looks normal. Can you guys see what we’re looking at?” he asked the crew, who could view the proceedings via their helmet cameras.

Can you try rotating the larger dish so we can see if there’s any damage behind, especially there at the mountings?”

“I’ll try.”

“Maryon, connect the portable, please. There should be an external input, but watch you don’t lose the cable.”

As Isaac rotated the large parabolic dish, she took a small computer from the toolbox. There was also a lead which she took from its holder. She plugged the lead into the computer and let it dangle. She clicked the other end into a small connector at the foot of the dish.

“Ready,” she said and switched on.

The display lit up and she followed the instructions from the technicians.

While they waited, Maryon watched Isaac elegantly maneuvering around the large dishes.

“Nothing noticeable anywhere,” he observed, “everything is perfectly intact.”

“Strange,” was the single word of judgement from the control room. “But the systems say exactly the same – everything in order. What about you, Maryon?”

The small computer concluded a series of tests and there was nothing apparently wrong. She showed the screen image to the camera.

“Anything else you want me to try?”

“Oh, no, it looks okay. Thanks.”

She heard them discussing various possible technical issues. She ignored the details. That was their job, she figured.

Isaac coughed again.

“You two can’t do any more out there. Better come back in.”

“Are you okay?” Maryon asked Isaac with concern.

“It’s nothing”

She packed the computer away and shut the toolbox.

They began the slow return journey.

The airlock neared in slow motion and for the last stretch they floated hand in hand steadily back to the spaceship.

“Thanks for the trip,” she said and squeezed his gloved hand.

“Likewise, Mary” he responded and led her around, as though they waltzed through the open space.

The equipment on the command bridge was a sea of lights, meters and machines decorated with joysticks and countless buttons. Accompanied by two officers, the ship’s captain, Albert Johnson, hovered in front of the panels. He had summoned the crew to a situation meeting.

While waiting for the last of the crew to float into the spacious chamber, everyone discussed the lack of communication with the Earth. It had lasted far too long.

Isaac was the last to arrive and he didn’t look to be improving. The pallor of his face resembled an overcast afternoon and he had black pouches beneath his eyes. It looked like he hadn’t slept in days – which might well have been the case, insomnia was also a side effect of the cryo chambers. The symptoms should not continue though, particularly because it was now nine days since they had woken from hibernation and the worst side effects should have been over. Maryon wanted to float over and take care of him, but that wasn’t allowed, and when she had a chance to speak to him privately about his condition, he had avoided the subject.

“As you all know, we still haven’t succeeded in contacting Earth,” the Captain declared, “we should have a long time ago but we’ve tried everything and there is no point in persevering.”

“It’s definitely not something with us,” one of the crew pointed out.

“That may be so,” Johnson confirmed. “Of course, something may have happened back at home. After all, we’ve been travelling on autopilot for six years. Many things may have changed. If I haven’t already mentioned it, I can inform you that the last automated update from IASA was received about four years ago. We also received a New Year’s greeting about a month before that. After that, nothing. Of course, a lot may have happened. Who knows what might have gone wrong? A natural disaster or a nuclear accident or something else entirely.”

“The government has probably just cut the budget and pulled the plug,” one astrophysicist laughed sardonically.

“It’s either sabotage or terrorism,” added another, “By the Northern Alliance.”

“Yes, yes,” Johnson said patiently, “Let’s not leap to hasty conclusions, we must wait and see what happens. Besides, the lack of contact doesn’t alter our mission. As such, we’re not in need of anything. We’ve plenty of supplies and we won’t be changing course. We’re still on route to establishing the furthest colony from the Earth ever attempted. That is why I’ve decided that the majority of the crew shall maintain their current assignments …”

Johnson paused suddenly. Something apparently unusual just behind Maryon had captured his attention.

She turned to see Isaac hanging lifeless in the air. His head hung downwards as though he was unconscious and from his face small red drops of blood flew into the air.

“Sally, assist Isaac, please!” the Captain ordered, making instant eye contact with the ship’s doctor, who was already on her way to Isaac. The Captain followed, while Maryon, filled with unease, pushed past her colleagues to get closer.

An astronaut grabbed Isaac and raised his head. Blood ran from his nose and eyes. When the crew observed this a simultaneous gasp was heard.

“We’ll continue the briefing later,” ordered the Captain, “return to your duties.”

But Maryon wasn’t going anywhere, she wanted to stay by Isaac’s side.

Three days later, Isaac lay clamped to a sort of bed in the sick bay. His illness had evolved into a fluctuating fever and extreme fatigue and he had several infections that left him pallid and weakened even further. All over his body tiny bruises appeared, as though he’d been struck by a shower of pebbles. The doctor still couldn’t say what was wrong but she was busy working on investigations in another room. It was difficult to perform medical tests in a weightless environment. Maybe it was the cryo chamber that had caused his illness, even though this type of serious side effects had never been observed before, as far as she could determine.

“How’s it going?” she asked as she floated in with a tray of food from the kitchen. The sight of his condition crushed her. The most frustrating thing was that there was nothing she could do to help.

He shook his head weakly.

“Drink a little,” she said and placed a straw to his lips.

While he tried drinking she laid a hand on his brow. Isaac only managed a few sips.

“Is it warm enough in here?”

“It’s fine,” he whispered, “but I’ve got a terrible headache.”

The colour of his skin was completely off, almost yellowish blue, he didn’t look like the old Isaac at all.

Just then, Sally floated in with the Captain following right after. They both wore a serious expression. They maneuvered over to the patient with the help of handgrips on the ceiling and walls. Sally checked the results from a number of machines that got their information from wires and meters attached to Isaac’s body.

“Are the straps too tight?” she asked.

“A little,” he said and swallowed. The effort seemed painful.

The doctor loosened the straps holding him to the bed. She did this as gently as she could.

“There. Does it help?”

He nodded softly.

“Listen, Isaac. Albert and I need to speak to you alone,” she said and looked at Maryon. Undoubtedly, it was a hint for her to leave.

She made no objection. There was no reason to create trouble. That was the last thing Isaac needed right now.

“It’s okay, she can stay,” he whispered, opening bloodshot and redrimmed eyes. Talking forced a little blood to run from his nose. The drops swept into space around them.

Sally quickly opened a locker and grabbed a bag of cotton wool and fished out a clump with which she carefully dabbed the bleeding to stanch it.

“Thanks,” he said and continued: “Just tell it like it is.” He closed his eyes. “I can take it.”

Even Sally, who should have been the most experienced with this type of conversation, seemed distressed by the situation. It clearly wasn’t an easy message to deliver.

The doctor inhaled deeply.

“I’ve examined your blood samples, Isaac, and … how can I say this?”

Until then, Albert had been silent but spoke to come to her aid:

“This is outer space, Isaac, not everyone can take it. Radiation levels are ferociously high out here, a hundred times what they are on Earth. Even though we’ve been frozen like ice cubes in the cryo chambers and surrounded by a thick lead shield, the background radiation of the universe has struck you somehow or other. All we can say is that radiation penetrates us, it breaks us down without us even knowing. We’re bombarded with particles, our insides in particular take a beating.”

The doctor nodded. It was as though Albert’s bluff introduction primed her to say what she’d come to say:

“Yes, and that background radiation has unfortunately destroyed some of the tissue in your body, more precisely, the tissue where blood is produced in the bone marrow.”

“What does that mean?” Maryon asked, a little frustrated at the long explanation.

The Doctor paused, but then addressed Isaac:

“It means you have leukemia. An acute form of leukemia, that is unfortunately quite aggressive.”

The news felt like a knife in Maryon’s heart, and she had a sudden feeling of nausea. She began to tremble all over. And she couldn’t hold back the tears that streamed down her cheeks like small pearls.

Without thinking she grasped Isaac’s hand and caressed it softly.

“And what can you do about it?” Isaac asked courageously.

Sally was also moved and wiped a tear from the corner of her eye.

“There’s … unfortunately, there’s nothing I can do. If this had happened back home you’d have been given a standard treatment with viral immunotherapy. It’s certainly a grueling course, but you would have managed it. But out here. That’s just not possible. I have neither the medicine nor the equipment.”

“But there is one possible solution, Isaac,” said the Captain reassuringly. He was more composed.

Maryon looked hopefully at him and while he spoke Sally fetched more cotton for Isaac’s nose and eyes.

“And what’s that?” Isaac asked, coughing.

“We can return you to the cryo chamber,” Albert said, “… indefinitely. The mission will go on without you and we will care for you until the day comes when we can wake you again for treatment. There may also be a time in the future when someone comes to replace us and you can perhaps be flown home for treatment.”

Isaac smiled indulgently. He knew what it meant:

“That may be in 10, 20 or even 50 years, Albert. By then you’ll be an old man.”

Albert apologised:

“Yes, Isaac, you’re right. You could say you’re going to miss the party, but you’ll survive.”

The decision was taken quickly. Less than 24 hours later, Isaac lay once more in a cryo chamber where he would remain in hibernation for an indefinite period. A whitish mist seeped from the chamber due to the extreme cold. The mist circulated in the room like a dead soul absconding from a tomb. This created an eerie, almost uncanny atmosphere. The low lighting did nothing to dispel this illusion. The place reminded Maryon of a burial chamber with a row of open empty coffins, except the one Isaac lay inside. Even though he was not at all dead, it felt as though he was. It was as though the remaining chambers were just waiting for the next crew member to die.

Her eyes welling up, she floated out of the room.

On the way up to the living quarters she wondered when she would next meet Isaac? The thought that she might then be an old woman was depressing but it was even worse to think that it was equally likely that she would never see him again. That she would live the rest of her life without him.

That had not been their plan. There was so much to experience, so much to explore and discover together on the future colony, but now she couldn’t imagine what tomorrow would look like without him. All her excitement and curiosity about the mission had evaporated and the joy she once radiated had been replaced by grief and sorrow.

Many times, she sought comfort in sleep, but sleep rarely came and instead most of the time she stared out a window at the vast universe whose merciless hidden forces had killed the one person she loved most in life.

That was how her days passed. While the rest of the crew resumed their habitual routines, Discover IV approached its destination which, according to the schedule, they should arrive at a few weeks earlier.

Even though Maryon was now working in the Bio Chamber, something that had always fascinated her, plants and biology, she remained quiet. Grief subsumed everything – not even the sweet desserts from the kitchen tasted good anymore. Conversations with colleagues didn’t help either, though they all attempted to cheer her with a kind word or a lame joke.

Nothing could make her happy.

Each morning she passed the room where Isaac lay frozen in his cryochamber. Every time she thought about how long he would lie there all the while time passed by on the other side. It was utterly unbearable and therefore she had reached a decision. A decision that felt right and disconcerting in equal measure. But despite her ambivalent feelings it was a course she was determined to pursue. It was also the reason she was now making her way to the bridge.

When she floated into the large room she found the captain in consultation with some astrophysicists. It looked like they were checking distances on a digital map of the solar system.

“I’m sorry, may I interrupt?” she asked tentatively.

“Why, Maryon, of course, any time. What brings you up here?”

“Can we talk, Captain? That is, alone. Just a moment. It won’t take long.”

The Captain signaled to the others to kindly remove themselves. Of course, this was done politely and without protest or comment.

“Stay nearby,” he said to them and leaned back in the air, as though the conversation required him to appear more relaxed.

“So, Maryon?”

She took a deep breath and prepared herself to deliver the tumultuous news:

“I’m really sorry, Captain,” she apologised in all seriousness and paused as she screwed up her courage: “But I have decided to … uh …”

She had rehearsed this in her mind repeatedly but now it was going awry because of her nervousness, forcing her to speak in an unbroken stream:

“… to resign from the mission, yes, I know it’s utterly wrong, cowardly even, like a deserter, but …”

Albert began to chuckle:

“You? Desert? Out here in space? Mary, Mary, Mary …”

He almost couldn’t stop chuckling and it annoyed her a little – she expected to be taken seriously.

He finally stopped laughing:

“Listen now, Maryon, one can only desert from the military and this isn’t the military but a research vessel. You know that,” he clucked indulgently.

“Yes,” she responded, “but I still think that what I want to do is more or less the same.”

He crossed his arms:

“What is it you want to do?”

That he had laughed so much hadn’t helped things. Her hands trembled and she didn’t know which way to look:

“I wish,” she stammered and tried to pull herself together but then suddenly she couldn’t hold the tears back any longer, “I wish to be put back in the cryo chamber, Captain.”

Albert shook his head as though he didn’t quite understand:

“What are you saying?”

“I want to wait till Isaac is well again. It means everything to me. That’s why I want to be refrozen.”

“Slow down, this is absurd.”

This utterance caused to Maryon to sob. She could hear how crazy it sounded, but she really meant it. She was genuinely so distraught at having lost Isaac that she was ready to follow him in anything, no matter how insane it sounded.

Albert approached and hugged her.

“Well, to be honest, I am not completely surprised,” he said and patted her back, adding that he and the crew had noted the attraction between them. “We’re not totally blind, you know,” he said and released her:

“Have you talked to Sally?”

She shook her head:

“No, I wanted to ask you first. I haven’t spoken to anyone about this.” He hummed and hawed a little over the comment:

“You’re aware of course, that I cannot condone such a drastic measure. Putting Isaac back into hibernation was … well, an emergency, a last resort. A perfectly unique set of circumstances. It isn’t something we just do. We need you. You’re part of the crew and …”

“But I love him, I really do! I know it sounds ridiculous and naive and … But I truly, truly wish to grow old with Isaac. Without him, I can’t bear the thought that my life should continue while his is suspended temporary.”

She wiped her cheeks with a forearm.

Albert bowed his head as though he had suddenly been struck by the same grief. Perhaps it was relief to him when they were interrupted by a bridge officer who floated in and discovered his weeping colleague.

“Captain, Maryon,” he greeted them stiffly, “Sorry if I am interrupting?”

Albert waved him away and returned his gaze to Maryon.

“Mary, I cannot accede to your request right now. You’ll have to talk to Sally about it over the next few days. She has to approve it, yes, she has to certify that you’re acting rationally and thinking clearly. Because I’m not persuaded that you are. In any case, I’m not qualified to judge and afterwards,” he raised a forefinger, “only afterwards I may reconsider the matter.”

“Thank you!” she blurted and gave him a hasty embrace and set off for the exit.

The ship’s officer looked wonderingly at her as she floated past a moment later but she was indifferent. She had to find Sally.

Over the next four days, she met with the doctor to explain and discuss her wish. Everything was laid on the table and Sally was friendly and receptive. It was comforting to finally open up about it. The conversations greatly resembled the consultations they had with psychologists back on Earth before being accepted onto the mission.

Every aspect of Maryon’s life was scrutinized. Her childhood and family, her upbringing and professional life and of course everything about her and Isaac. Sally learned everything. How they had met during preparations for the mission almost 10 years before. About their first kiss on the roof of the International Aeronautics Space Administration concert hall in Florida, AngloAsia. And what they had spoken of in secret, at night, alone in their rooms, without anyone else knowing about it. She also recounted how Isaac had followed her to the cryo chamber and held her hand as the doctors prepared her for freezing. Finally, Maryon told Sally about their shared dreams and plans and everything they intended to experience on the new colony.

After more days Sally assessed that Maryon – notwithstanding the obvious grief and trauma – was in fact competent enough to take such a drastic decision, which, from Maryon’s perspective, was actually quite rational.

After that, Albert was included in the discussions. Despite being astonished that she and Isaac had enjoyed a prolonged and secret dalliance on Earth, he tried to stay objective about the whole affair and concluded that love was clearly something ungovernable.

The toughest part was that Maryon was forced to tell her colleagues the news. That included the soon to be sole remaining biologist who would be responsible for cultivation on the colony in the very imminent future. Fortunately, her colleagues received the news with equanimity and understanding.

Nor was it easy when she had to tell the remainder of the crew at morning assembly. She shook within and her voice cracked a little but even though a few people considered her to be out of her mind, most were pretty understanding or at least indifferent.

It was her choice, they shrugged.

Some days later, everything was in place.

“I don’t understand why you would subject yourself to this again,” the doctor said as she braced Maryon’s legs and arms in the crate that would soon be her hibernation residence for an uncertain period.

They were still alone in the room, primarily because Maryon was naked. Clothes were not permitted in the cryo chamber. Her head had been shaved once again; all hair fell out after freezing anyway. Binding her limbs was necessitated by the zero gravity.

Maryon looked down at her flanks. The braces resembled handcuffs and they clicked each time Sally locked them. When it was done, she couldn’t move her arms or legs. In every sense, lying in the cryo chamber was a horrible experience. It was like being trapped in a coffin while still alive. There was some sort of cushioning beneath her, but it was hard, unyielding and cold. The material was synthetic. Various pipes carrying plastic tubes protruded from the inner surfaces. Even now, she was nauseous at the thought of what they were to be used for. She clearly remembered how unpleasant it had been the first time on Earth.

“Shall we begin?” Sally asked and lubricated the end of a plastic tube with some cream.

Maryon nodded and opened her jaws wide. Sally lodged two mouth guards in her mouth to hold it open. Then she guided the tube through the gap between the guards and rested it on Maryon’s tongue. There was a slight suction at the tip and the lubricant tasted minty.

“Are you ready?”

Maryon nodded.

Then Sally began to push the tube down her throat. It was hardest to get the tube past the uvula. Maryon immediately felt the first gag reflex. Sally hit a snag and Maryon began to cough mucus and saliva.

As a reflex reaction, she struggled to slip free of the braces, but Sally just pressed her head down while she pushed the tube further down.

It felt as though a long slender creature was creeping down her throat. She hacked and coughed. Sally encouraged her to relax and take it easy, it would ease the discomfort, but it was completely impossible to ignore the sensation of something being forced down her gullet.

“Now, I’m going to remove the shields, but you mustn’t bite the tube. If it gets punctured, we’ll just have to start over,” she said.

Maryon gasped for breath.

“You’re doing great,” Sally added, “that’s it. We’ll progress quickly down into the lungs now.”

Maryon nodded nervously as Sally carefully fed another soft tube into her – this time through her left nostril. The tube cut into the soft tissue lining her nasal cavity and Maryon was sure she would soon start bleeding, but Sally just continued snaking the tube down past her throat and on through her airway.

“Almost there,” she tried to encourage her but Maryon struggled to remain calm. It felt dreadful.

“That’s it,” Sally concluded, “finished! Now we can initiate the freezing process.”

Through tears, Maryon vaguely glimpsed Sally’s silhouette.

“Now, I have to ask you one last time. Are you sure about this, Maryon? Utterly certain?”

She nodded. She was completely sure.

Sally shook her head:

“Then I’ll seal the chamber now,” she said. “I hope we meet again in the future. Godspeed, courageous woman.”

“Likewise,” Maryon murmured. It was hard for her to say anything with the tube in her mouth.

“Sleep well,” the doctor smiled and activated the ponderous chamber lid, which slowly began to descend upon Maryon.

When it had descended fully, the only light that was visible came from a small visor in front of Maryon’s face. From the other side of the chamber’s thick walls she could hear people moving about; must be technicians starting the freeze, she thought. That wasn’t part of Sally’s job.

A man tapped on the pane and waved to her.

It was claustrophobic and only became worse when she shortly afterwards felt the ice-cold, liquid refrigerant strike her skin. Tiny flying beads settled on her body and as more refrigerant flowed in, the beads became floating and swaying figures that grew in size. The liquid penetrated her nose and ears. It lay on her stomach, along her thighs and calves and around her arms and breasts. After 10 or 20 seconds she exhaled the last air in her lungs and resisted inhaling as long as she could, but in the end, it was, inevitably, impossible to hold her breath.

She had to breathe.

When she did freezing liquid flooded into her mouth and lungs. She felt as though she was drowning and choking at once. It was like she had swallowed gallons of liquid and she tried to retch it out while her arms and legs sprawled. Her knees struck painfully against the immovable chamber lid. To her surprise, the liquid didn’t kill her; the small tubes were steadily conveying oxygen into her lungs.

She drowned but was kept alive at the same time.

A hum began to vibrate around her. The cryo chamber was accelerating the process. Then the cold arrived and it came with a vengeance. At high speed, it shot through her skin and bones and she felt her hands, feet, legs and arms growing numb at lightning speed. Her insides hurt. Her organs were shutting down. She wanted to scream but even her jaw was stuck and couldn’t open. It too was frozen.

An ache enveloped her head. The pain was indescribable and she thought she would die.

That was the last thing she remembered.

Then all turned black.

Arrival

ELAI CLOSED HIS EYES. Tried to stay calm. It wasn’t his first time flying through a moon’s atmosphere, but no one had ever landed on this moon before. He tried to ready himself mentally for what was about to happen. Not allowing any room for fear.

Focus on breathing, he commanded himself. Relax your muscles.

But his thoughts would not switch off and he knew what would happen during the landing. His body would be pummeled like never before, his weight would feel several times heavier than it actually was and he would feel sharp pain as he was crushed down into his seat.

Everything was dizzying and he feared he was going to pass out. Feared that the enormous spacecraft would blister and buckle and be incinerated like a hurtling meteorite. That the cabin would feel like a prison and the claustrophobia would be suffocating. The only light in the room came from tiny flashing diodes that trickled across the pilots’ panels and from the stressful warning lights in the ceiling that were almost designed to induce panic. All the while an automated female voice would come through the cabin speakers, speaking slowly and emotionlessly, announcing that the ship was about to enter the outer exosphere of an unknown moon. That the retro-thrusters would ignite and create tremors as big as an earthquake.

“Yee-haw,” Sickarius roared from the front of the cabin as they began their descent.

No one shared his enthusiasm.

A jarring jolt to the hull dislodged a droplet of sweat from Elai’s forehead. He wiped it from his eye with the back of his arm but hurried to grip the safety straps once again. Every muscle in his body tensed. Rapid heart rate and desperate breathing. He noted a throbbing vein in his temple pumping blood to his brain. Pain shot through his body and he felt like screaming, but he locked the pain inside behind gritted teeth.

It would soon be over.

Soon they would be on Exnihilo.

*

The anxiety welled up from below. It felt like an incipient tremor around his feet that made his legs vibrate and crumple beneath him like towers collapsing. His muscles quivered but he tried to ignore the trembling and straightened his head and gazed out at the audience.

An auditorium of eyes peered at him.

He gripped the podium firmly for support. His fingers clutched its timber edges tightly. He swallowed. His glance flitted back down to the script that glowed on the display. He hadn’t imagined he would be so nervous, but the huge number of attendees took him by surprise. The hall was packed to bursting point and among the audience were some of the most influential people in the world. There were even rumors that the research and science minister for The Interhumane Synedrion was present.

The seminar was being held at The Institute of Human Biology and Science in Main, a global conurbation in the Free Worlds’ SafeZone on Earth. It was Elai’s third trip to Earth – to that tiny sliver of the planet that remained habitable for humans. Once again, it was a fascinating experience. To be transported over the scores of prominent buildings erected on top of the city, perched on massive iron pilings towering over 100 metres above ground. Up here, the wealthy few could enjoy the vista of a sky blue heaven that could only be experienced in all its majesty above the city smog.For Elai, it was an experience in itself to not be caged inside a glass case as people were on the moon in the multiple domed colonies where the only view was of a barren grey landscape and an atmosphere so thin the light from heaven was never refracted into enchanted blue nuances as on Earth. Not to mention the solidity of motion on Earth. To stand with your feet solidly planted on ground and have proper gravity anchoring you. An authentic weightiness. If only the ground beneath his feet had not been so contaminated, humanity might still have had a permanent place on the planet.

Everyone should experience Earth, Elai thought – even in its worst state, as now.

However, the simple truth was that Earth was destroyed. There were only a few places where it was safe to spend any length of time. Most major rural areas were uninhabitable due to pollution, radioactivity and toxic residue from the war. Almost all of the formerly major cities were deserted and there was no desire to rebuild them. Even Main, which in its lower quarters was characterized by densely populated high-rises, bleak industrial landscapes and polluted aeropods stacked seven high in the heaviest traffic areas was, in the minds of many, an extremely hazardous place to be. There was a reason the city’s more salubrious neighborhoods were built on pillars. From a distance, the horizon of the city resembled a forest of toadstools. Radiation was most intense on the ground surface, up higher it was somewhat less but you still had to eat anti-radiation pills and all the buildings were equipped with air scrubbers.

The Institute, where he had a room, was housed in an architectural masterpiece more than 180 years old that had somehow survived The Total War virtually unscathed. Unsurprisingly, it had become a recognized landmark in Main. An edifice with beetling, elliptical towers and numerous glass-enclosed walkways where people swarmed back and forth like ants. Here, in the midst of this fascinating architecture, Elai found himself surrounded by hundreds of respected and influential scientists. They had been invited to a seminar on the future of humanity. Not only had Elai been invited, he had also been granted the privilege of delivering the opening talk. A talk that would touch on ethics, science, philosophy and biology. Preferably with some reflections from his doctoral thesis:

What is life?Biological Definitions and the Consequences for Our Society

It had taken him four years to complete his research project. He had written it while he was staying at the Luxur space station orbiting Mars. He had examined microscopic metabolic samples from the subsoil on an asteroid and, despite the extreme conditions, he discovered that primitive strains of bacteria could be found deep in the asteroid. With this he confirmed the widely held opinion that life on Earth had originated in space and ipso facto could also live in space – a topic that was very relevant because of the perennial quest to find suitable locations in space to construct new colonies.

“What is life, in fact?” he asked the auditorium and allowed the question to hang in the air.

Several earnestly listening participants crossed their arms and looked at him with a degree of skepticism. It was clear they weren’t going to be bowled over by a novice researcher.

He hurriedly continued, asking whether life can be defined as the immortal DNA we all contain and which was originally copied from generation to generation via gametes and which determined the enzymes and proteins that formed and controlled our cell metabolism? Of course, the question was rhetorical because if it was correct then none of the attendees in the conference auditorium were technically alive. The natural reproductive power of humanity had been obliterated more than 100 years before during The Total War. Today, children were produced in enormous fertility factories and were brought up in so-called family homes.

He then went on to dissect the concept of life. He spent some minutes discussing whether life could be defined as an entity which absorbs solar radiation. This could not be the case either as there were bacteria-like organisms deep in the substrate of the asteroid he had spent four years studying. The bacteria had been found in a suspended state and survived perfectly well for millions of years in the absence of light. Life could in fact continue indefinitely while set on pause.

What about water? Does life depend on water? Or is life simply a synonym for an entity that can die? Something that ceases to exist? Or is life a self-generating chemical system capable of evolving?

Elai spoke for almost an hour on the criteria that might define life. He exhaustively examined the subject by discussing such topics as independent motion, feeding and digestion, respiration, growth, propagation and reproduction, reactivity to stimuli and homeostasis. But it was only when drawing his conclusions that he began to speak about the issues the seminar was dedicated to.

“Countless studies have told us that life expectancy is decreasing year on year. Latest figures say that our average life expectancy is now just 41 years. And we are far from resolving the mystery of the Merciless Death and finding an answer to why humans die so suddenly and so early. Some say that humanity as a species is dying out – just as many species that lived before us are now extinct. But this is an excessively pessimistic viewpoint which also suffers from the fatal flaw of being false. Even though we no longer produce children as our ancestors did, our wealth of fertility factories ensure enough people are produced to expand our civilisation and that the human species will survive. What we need to ask ourselves is …”

An alarm sounded through the auditorium’s speakers:

“This is an emergency announcement. Please remain calm and evacuate the building via the nearest exit. This is an emergency announcement …”

The audience rose to their feet as one. Elai looked uncertainly about but also promptly left the podium.

When he arrived backstage, one of the organisers approached him:

“Sorry, we’ve had a bomb threat.”

The host took Elai by the arm and led him to an emergency exit.

“No doubt it’s Ultima Spe up to their old tricks again,” he commented angrily. “That dissident group is driving us to distraction. Every time we have someone from the Synedrion visiting, we get threats and vandalism. We have to increase manpower and security. Come, this way …”

Later that night, Elai was alone in his room. He stood and watched the city with its many buildings and pulsing traffic. Like splinters of light, scores of aeropods in countless sizes and colours sailed past the Institute. They created branches of light that wove between the buildings like shimmering threads.

The bomb threat had passed without incident but it had ruined his talk.

The conference itself had gotten off to a bad start because of the rebellion, whose only purpose was to discomfit the members of The Interhumane Synedrion.

Elai was well aware that many people quietly blamed the Synedrion for the poor state of society. The dissident movement, however, went further in their criticism, resulting in uprisings, conflict and demonstrations. Time after time, the Synedrion was forced to deploy police to defuse conflicts. Some viewed this as a heavy handed response to society’s critics and this meant faith in the leaders of Synedrion was further weakened. That there hadn’t been a revolution yet was probably only because the 12-man council of the Synedrion was regularly replaced, simply because they too died of the Merciless Death.

But, as Elai frequently reminded people, their form of government had also benefited humanity greatly. Among other things, it was thanks to the Synedrion that humans still existed. At the end of World War III, radioactive, biological and chemical pollution had meant the few million people left after the war had serious problems having children. Following the second census, population growth was already showing minus figures. Fertility doctors tried everything from micro-insemination to follicle stimulation to in vitro fertilisation. But none of the traditional methods worked. Very few pregnancies resulted. The majority miscarried after a short time.

It was said that this was nature’s way of punishing humanity.

That is why the first Synedrion members allowed all types of radical experiments to secure a future for human life. Experiments were carried out on brain transplantation in humanoids, reproductive cloning of humans and human in vivo fertilization in animals, but none of these controversial methods yielded significant results. Cybernetic body replacement research also intensified. From a neurophysiological point of view, brain researchers and system architects earnestly attempted to copy and reconstruct the human brain’s unique self-consciousness in computers and adapt the spiritual life that only man is known to possess.

This too failed.

After years of grinding failure, however, a breakthrough was made in the artificial reproduction of humans. Scientists succeeded in creating the first human from scratch in a lab without any physical connection to other people – a fetus that could grow and become viable without ever having been inside a living organism or surrogate mother. That breakthrough was a turning point and was now regarded as the start of a new era, a positive bright spot after a dark episode in human history.

The Interhuman Synedrion immediately initiated construction of the first fertility clinics. These grew into sprawling facilities where children were manufactured in their thousands, creating new generations of workers to rebuild civilisation. Without these initiatives, people would most likely not have existed today.

Everyone ought to be grateful, Elai thought.

Just then a computerised voice interrupted his thoughts. The voice said there was someone outside his door attempting to contact him.

Elai walked to the little intercom by the door. On the screen he saw the image of two security goons: Burly, black-suited and baleful suspicious. He passed his hand across the sensor and the door slid open at high speed. Chill air struck his face. The two men said nothing, just looked suspiciously at Elai and around the room.

“Can I help you with something, gentlemen?” he asked but they didn’t reply. They just stepped to one side.

A few meters behind them a small man emerged from their shadows. Small, with a friendly expression and a well-groomed, polite side parting. Elai knew him well but had never met him face to face: Martin Chen.

“Good evening, Elai. Hope I’m not disturbing you.”

Elai shook his head. Of course not.

The Minister of Science and Research regarded him affably:

“Excellent opening today. A shame you were interrupted.”

They shook hands.

“Thanks. Many thanks. Yes, it was distracting. Seems Ultima Spe’s methods are getting rougher.”

“Yes, it is of some concern. Perhaps someone should listen to them.”

Elai didn’t understand what he was getting at but the minister quickly changed tack:

“Elai, there’s something I want to talk to you about. Or rather, ask you. May I come in?”

“You’re welcome to,” he said and stepped back with an outstretched arm to invite him in. Instead, one of the goons marched into the bedroom.

“He just needs to check everything before I enter. Routine procedure,” Martin Chen said. “There’s so much trouble nowadays.”

Elia nodded and remembered the room was not as presentable as it might have been.

“It’s a bit messy,” he apologized.

“I’ll live,” the minister said as he was given the green light by the security officer who had returned from his inspection. The minister entered and the muscle departed to wait outside. Elai interpreted this as meaning he could close the door.

“Can I get you a drink?”

He took a small bottle filled with green liquid from the refrigerator.

“No, thanks. I shouldn’t so late in the day. But please have something yourself.”

The minister stood in front of the window in exactly the same place Elai had been standing a moment before:

“Let me get straight to the point, my time is limited.”

“Of course, please speak freely.”

Elai drank from the bottle.

“One of our researchers has picked up a signal, a radio signal in fact.” A radio signal? That sounded dusty.

“The scientists think it’s a message from outer space, but I’m not so sure.”

More interesting, but quite unlikely:

“I agree,” Elai said, “but you’re here talking to me so there must be something you find plausible in the claim.”

There was no reason to undermine the minister’s scientists, even though they were certainly mistaken.

“Exactly,” he said and looked at Elai. “Let me explain. A scientist named Jean Miller discovered the signal quite unexpectedly in connection with another project. The signal is perpetual and originates on Jupiter’s moon number 64 that was discovered about 130 years ago. Scientists now refer to it as Exnihilo because the signal seems to appear from nowhere. The signal is unidentifiable and has travelled millions of miles across space. It is tenuously weak but exhibits all the properties one would expect from a signal from an intelligent civilisation. However, it is limited to a very narrow frequency band at 2.169 MHs so it is quite far from the hydrogen line. Jean Miller and his team of researchers insist, though, that it can only evidence extraterrestrial intelligence.”

“Interesting,” Elai remarked.

The Minister continued:

“Yes, of course, we already have people working on the case and they’ve confirmed the authenticity of the signal. It looks like the real McCoy. Jean Miller continued analysing the signal and succeeded in decoding the data. There’s a discernible pattern.”

“There are lots of patterns in nature,” Elai said, “The whole universe is a system. A single vast clockwork. The intelligent watchmaker – or makers – haven’t been keen to reveal themselves, though,” he observed.

“You are correct, but think if we could get there or at the very least learn a little more about it. In any case, the structure of the signal indicates there is an intelligence behind it. You see, the signal is actually a celebrated mathematical function that is emitted at a fixed interval. Precisely like a primitive watch counting down. The signal is running down, so to speak.”

But that wasn’t proof of intelligent life, thought Elai. Many living organisms also possessed an internal clock counting down, that wasn’t new. The cardiac muscle of every creature had an expiry date, but this didn’t endow them with intelligence. This was also true of other entities in the universe. Suns burn out and extinguish themselves. Even the universe itself must have an end date, just as it has a start date. But yes, it was nevertheless remarkable to receive a radio signal that seemed to be counting down. If it was genuine and not some elaborate hoax, who then had started the clock? What was the clock counting down to … and was it good or bad? Was it a warning?

“Your thinking is almost audible, Elai,” the Minister said with an arched eyebrow. “We’re asking a lot of questions, too, but what we really need are answers.”

It was clear that so many scientists working together would be far ahead of Elai. He drained the bottle and flipped it absentmindedly toward the trash can. The automated trash can opened and glowed faintly as it swallowed the bottle whole, making a crushing sound as of paper being crumpled.

“Then what can I help with? Surely, there’s nothing I can do?”

“Don’t be so modest, Elai. Your performance today – until the unfortunate interruption – certainly shows you have much to contribute. I actually hoped you might help us find some answers to our questions by going on an expedition to Exnihilo.”

Elai didn’t know what to say. He already had a hundred plans for the immediate future. Career. Projects. Research. Students who needed feedback on their assignments. But this …

“It certainly sounds exciting.”

“I had hoped you’d say that. Unfortunately, I have to put some pressure on you. I need a quick decision from you. Our scientists have calculated that if we dispatch a crew before the end of the month it will reach the moon a few days before the countdown ends. Time flies, frankly, and not in our favour.”

“Provisionally, I am interested, Minister …”

Of course Elai wanted to go.

Martin turned and seemed satisfied. He walked over and placed a hand on Elai’s shoulder.

“I’m glad to hear it.”

His guest motioned as though leaving the room – prematurely.

“Who else will be on this expedition, if I may ask?”

The Minister stopped and turned to face Elai:

“You will be given more information but as far as I remember, the General Secretary thinks a crew of six should be designated for the assignment. Two pilots, an astrophysicist, a surgeon, a mathematician and an astrobiologist, namely you, all going to plan. As you’ve probably surmised, I don’t have sole decision-making power on this one. You’ll have to undergo a range of tests. Training and so forth. But let’s put it this way, my word has some weight. The journey will take around ten months there and back so you’ll be in cryohib most of the time but you already have experience, don’t you?”

Of course, he nodded. He had been gas hibernated in a chamber when he was transported from the Moon to a space station orbiting Mars. Not unpleasant at all.

The minister waited at the door. Elai opened it for him.

“Someone will be in touch. We’ll meet again before launch day. Thank you once again for your input today. Abbreviated as it was.”

Elai shook the minister’s hand.

“I should thank you. For the opportunity.”

The words sounded stilted. He hated when that happened and a conversation stumbled awkwardly.

The minister departed with the two goons trailing him.

Elai stood in the doorway a moment. Listened to the traffic, which from a distance sounded like an irregular engine, spluttering in the wind.

He slouched over to the bed and threw himself down. Landed on the deep quilt that wrapped itself cocooned around his body. Just now, he felt very, very fortunate. It was as though a tiny seed planted in his heart had begun to sprout. A feeling he had not had for many years. For a moment he asked himself what it actually was he was positive about? Had he forgotten to be realistic? The mission would be prolonged, dangerous and in the worst case, it had the potential to be deeply disappointing.

But after mulling it over awhile, he raised himself up on his elbows. He suddenly understood what it was that made him so happy.

It was hope. A hope that the journey would not only change his life, but also his understanding of life. What if life from outer space could once again bring life to humanity?

*

There wasn’t much life in Andy Stevens. He sat in the chair opposite and looked as if he had passed out; drool and flecks of vomit dribbled from the corner of his mouth. It pooled in his lap and on the floor in front of him. The gastric juices were cloudy and lumpy and spattered everywhere. The stench was tart and acidic. His head dangled from side to side each time the ship rocked and twisted its way through the foreign atmosphere.

Elai turned his gaze away from the sight and wondered if he was about to throw up also. In fact, it was quite normal when subject to such powerful G forces.

Through the speakers an automated female voice informed the crew that penetration of the exosphere was almost complete and that the 60,000 tonne space vessel had entered the final stage of the descent. The only thing now awaiting them was the imminent landing on the strange moon.

Captain Miriam Smith’s duty now was to manoeuvre the ship to a safe landing site. She had to avoid landing on a slope or in a crater. In general, she was compelled to avoid any unstable substrates, which was particularly challenging as they knew practically nothing about the moon’s surface. Simultaneously, she had to localise a relatively extensive area. It had to be large enough to contain the 700 meter wide and 500 meter tall spacecraft, cream colored with soft lines and spacious forms. Though its bulk mainly concealed the enormous engines, massive fuel tanks and efficient fusion turbines that were required to fly the passengers and their heavy payload millions of kilometres through space.

Miriam Smith sat in the forward place in the cockpit. She was strapped into a special chair surrounded by instruments and switches. In the chair she could manoeuvre the ship using a U steering wheel, various joysticks, panels, grips and pedals. She was a skilled pilot with many years’ experience of flying freight to awkward destinations. Landing a spaceship on unknown terrain in chaotic weather conditions was nothing new for her. That’s what Elai had overheard several times when she recounted – or rather boasted – about the countless missions she had completed.

He now hoped she had been telling the truth.

Alongside her sat Sickarius Spence, the co-pilot. An ambitious colleague who had worked his way up through the Synedrion’s pilot program through elective training courses he himself had paid for. His success was down solely to his unyielding self-discipline and strict self-denial of many of life’s pleasures. He had sacrificed everything – friends, girlfriends, leisure pursuits. He was fiercely dedicated to his profession and the missions he was assigned as part of The Interhumane Synedrion.

In the seats behind Elai sat Perch and Gillian. Perch was an astronomer and astrophysicist. He had launched communication satellites along the outward journey. The satellites permitted them to establish a superluminal communication channel with The Interhumane Synedrion so they could maintain real-time dialogue. The superluminal communication was based on a quantum mechanical system that made it possible to transmit information faster than the speed of light across inconceivably long distances via communication satellites. Perch had launched satellites at approximately 20 day intervals. This meant he had been frequently woken from cryohib. All the other crew members had lain in uninterrupted hibernation for the nine month long journey, so while the others slept and Scout Voyager flew through space on autopilot, Perch worked alone on the upper deck.

Gillian was the ship’s doctor. Their lifesaver should anything go wrong. At the start of the expedition she had been occupied with immersing herself in electronic paperwork; investigations or research material maybe – she never revealed it to anyone. After hibernation, she had commenced work in the clinic and operating theatres on the first deck. Here her time was taken up in opening creates from the hold, installing and configuring medical equipment in spite of the challenge posed by the weightless environment. Impressive.

What on earth would she do when there were no more crates to prise open? Elai wondered. And what in the world was she preparing for?

As their approach entered its final stage, Miriam ordered the crew to hold on tight. Prepare for a bumpy touchdown, as she phrased it. The landing culminated in a climax of crashing and battering hair-raising tremors in the spaceship’s massive titanium exoskeleton. Tightly shut hatches and lids shot open. Objects were strewn all over the floors. Metal instruments and other items rattled around the rooms as though a tempest swept through the interior of the ship. No one, not even the highly experienced pilots, had imagined such a raw and stormy atmosphere.

When the landing gear of the ship collided with the implacable rocky surface of Exnihilo, the powerful shock was like being struck by a massive explosion. The soundwaves penetrated the hull and triggered a loud, massive crash and trembling that clearly indicated the spacecraft had reached its long awaited destination – a harsh, tough and icy moon – in the uninhabitable zone of the solar system.

The fusion turbines soon began to wane in strength. The almost intolerably loud noises slowly abated and Elai felt the engines decelerating and the energy level of the machinery surrounding him began to decline.

For a brief moment he caught a glimpse of a scenario he had never imagined: that they would never again escape that inhospitable place. That all the energy would vanish completely, the oxygen would be consumed and the spaceship would become their coffin.

Just then Sickarius loudly announced that the landing had been successful. No problems. Like a game, he confidently joked. He seemed almost euphoric. Elai unhitched the harness and looked at his hands. His palms bore red weals from the harness straps.

Gillian ran past him. She crouched in front of Andy, whose head still drooped.

“Andy, how do you feel? Here, drink some of this.”

Andy opened his eyes and took the water flask she offered him.