Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Publicacions de la Universitat de València

- Kategorie: Geisteswissenschaft

- Serie: Biblioteca Javier Coy d'Estudis Nord-Americans

- Sprache: Englisch

This collection of essays brings together an international group of scholars who discuss various facets of the American South in popular culture, literature, the arts, and throughout history. It includes reflections on place, on the importance of memory in shaping individual identity, and on race, class and gender. All the contributions confirm Howard's Zinn's idea that the South "is not damnable, but marvelously useful, as a mirror in which the nation can see its blemishes magnified, so that it will hurry to correct them." This volume sheds light on the "marvelous" sides of the South though it does not overlook its darker ones, thus making it possible to better understand this peculiar region.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2024

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Facets of the American South: Essays on a Peculiar Region

© Edited by Gérald Préher and Frédérique Spill

Reservados todos los derechos

Prohibida su reproducción total o parcial

ISBN: 978-84-1118-320-8 (papel)

ISBN: 978-84-1118-321-5 (ePub)

ISBN: 978-84-1118-322-2 (PDF)

Depósito legal: V-484-2024

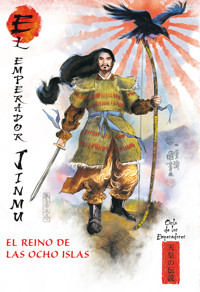

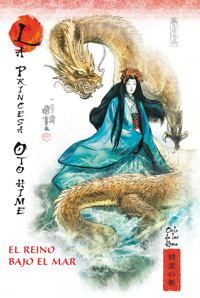

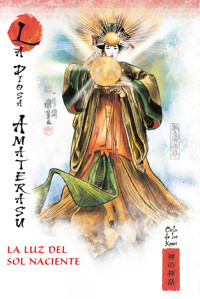

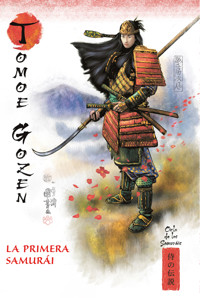

Imagen de la cubierta e ilustraciones: Sophia de Vera Höltz

Diseño de la cubierta: Celso Hernández de la Figuera

Publicacions de la Universitat de València

http://puv.uv.es

Impreso en España

In memoriam

M. Thomas Inge

John W. Lowe

Table of Contents

Facets of the American South

GÉRALD PRÉHER AND FRÉDÉRIQUE SPILL

PART IIMAGES OF THE SOUTH IN POPULAR CULTURE AND LITERATURE

Edgar Allan Poe, Richard Corben, and the Southern Gothic in the Graphic Narrative

M. THOMAS INGE

The Vicious Circle: “White Trash” Mythology in Dorothy Allison’s “River of Names”

HANA ULMANOVA AND ZUZANA JOSKOVÁ

Colson Whitehead’s Multifaceted Mode of Storytelling: Bridging Myths, the History of the South and Popular Culture of the Digital Age in John Henry Days

FRANÇOISE CLARY

Beasts of the Southern Wild in Shattered Mirrors: Writing after Katrina

JACQUES POTHIER

PART IITHE POWERS OF PLACE

Katherine Anne Porter and Mexico: From Displacement in Space to the Space of Displacement

ELISABETH LAMOTHE

“A Small, One Might Say Almost Claustrophobic World”: Kinship and the Urban South in Madeleine L’Engle’s Ilsa

SUZANNE BRAY

A Peculiar Sense of Place: The Fascinating Side of New Orleans in Elizabeth Spencer’s Fiction

STÉPHANIE MAERTEN

Facets of the South in Toni Morrison’s Home and Jazz and Eudora Welty’s “Flowers for Marjorie” and “Music from Spain”

PEARL AMELIA MCHANEY

Edward P. Jones’s D.C., Where a Southern Past Informs the Present

AMÉLIE MOISY

PART IIIMEMORY AND IDENTITY

Peter Taylor’s Art of Storytelling in “A Spinster’s Tale’ and ‘The Old Forest”

JADWIGA MASZEWSKA

Revisiting Slavery Through a Contemporary Lens: Phyllis Alesia Perry’s Stigmata

YOULI THEODOSIADOU

Negotiating Family Past in David Bradley’s The Chaneysville Incident and Octavia Butler’s Kindred

PATRYCJA KURJATTO RENARD

Short-Lived, yet Long Remembered: Exhilaration and Other Escape Strategies in Ron Rash’s The Risen

FRÉDÉRIQUE SPILL

PART IVRACIAL STRIFE

“The Celebration of a Gaudy Illusion”: Juneteenth and Black Texans after the Great War

ELIZABETH HAYES TURNER

The Mississippi Summer Project of 1964 through the Eyes of Freedom Summer’s Northern Clergymen

MARK NEWMAN

“It took an old woman and two children for that”: Minority in William Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust

STÉPHANIE EYROLLES SUCHET

Revisiting the Mammy Image in Kathryn Stockett’s The Help and Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman

SUSANA MARÍA JIMÉNEZ-PLACER

PART VVISIONS OF THE SOUTH

“The only earth we will ever have”: Early Twentieth Century Southern Women’s Clubs as Forerunners of Environmental Reforms in the Contemporary Globalized World

VALERIA GENNARO LERDA

The Absurd in the South: The Case of Flannery O’Connor

MARCEL ARBEIT

Reasonable Use of the Unreasonable: The Supernatural in Reynolds Price’s Love and Work

SIMONE VAUTHIER

Toni Morrison’s Paradise and the Ghosts of Reconstruction

SUSAN V. DONALDSON

Minimal Maneuvers between Dystopia and Utopia in Two Stories by Breece D’J Pancake

INEKE JOLINK

The American South in Denmark: The Visual Art of William H. Johnson

CLARA JUNCKER

CONTRIBUTORS

Facets of the American South

Gérald Préher

Artois University, France

Frédérique Spill

University of Picardie Jules Verne, France

[T]here is something about writers from the South. There is a certain flavor to Southern literature that distinguishes it from other regional writing, a ferocity about it…

Margaret Eby, South Toward Home: Travels in Southern Literature (2015).

[W]hat makes the oft-remarked Sense of Place in Southern fiction so important is the vividness, the ferocity even, with which it implies social and community attitudes. This is because the writer’s own experience of a place has involved those attitudes so pervasively that for the writer to evoke the place is to confront the community’s values.

Louis D. Rubin, The Mockingbird in the Gumtree (1991).

In his introduction to The Future of Southern Letters, written in the middle of the 1990s, John W. Lowe notes that “most of today’s southern narratives … aspire to mirror a culture in the throes of dynamic and dramatic change” (6), which he feels has always been at the core of southern storytelling and, it is tempting to add, at the center of southern life. This idea of a mirror is also present, but from a different perspective, in Howard Zinn’s The Southern Mystique where it is suggested that “[t]he South … far from being utterly different, is really the essence of the nation… . It contains, in concentrated and dangerous form, a set of characteristics which mark the country as a whole” (218). Zinn’s analysis presents the region as the embodiment of a specifically American way of life. He feels that “with this approach, the South becomes not damnable, but marvelously useful, as a mirror in which the nation can see its blemishes magnified, so that it will hurry to correct them” (263). Such an idea is reminiscent of the theories according to which the South is becoming more and more like the rest of the nation, that the South, as Josephine Humphreys puts it, is a “disappearing subject,” which implies that it has not completely vanished, although Byron E. Shafer and Richard Johnson, in their study of the economic and political situation of the region, have suggested that “the end of southern exceptionalism” has come and that after the Old South, the New South, there might just be “No South” now. Their focus is on convergence with national norms rather than divergence, though there is no doubt that southern culture remains distinctly regional in terms of race, class, religion and the communal spirit. The situation has obviously changed since W. J. Cash complained that “the majority of the contributors to I’ll Take My Stand were primarily occupied with the aristocratic notion in their examination of the Old South. And it is true, finally, that they took little account of the case of the underdog proper, the tenants and sharecroppers, industrial labor, and the Negroes [sic.] as a group” (382). The “backward glance” Allen Tate referred to in his 1945 essay “The New Provincialism” can certainly be applied to most, if not all historic, literary and artistic productions as the development of trauma studies shows, but this is not solely a southern concern. In fact, as Charles Reagan Wilson puts it, “[t]he South is still struggling with its heritage of tragedy and suffering and still invested with the hope that suffering can lead to salvation” (300); the recent removal of Confederate monuments and memorials certainly has led to suffering and incomprehension for some, but it also means that the South is moving on.

Changes have indeed occurred and are still occurring. Introducing South to the Future, Fred Hobson asserts that “[t]he reality—and, even more, the mythology—of the poor, failed, defeated, backward-looking South has long since been replaced by the mythology of what in the 1970s came to be called the Sun Belt—prosperous, optimistic, forward-looking, air-conditioned, self-congratulatory, and guilt-free” (4). Still, some contemporary writing does seem more inclined to look at the remains of the past in the present—Kaye Gibbons went back to the Civil War (On the Occasion of my Last Afternoon, 1998), Josephine Humphreys researched the Lumbees in South Carolina during that same period (Nowhere Else on Earth, 2000), Ron Rash and Terry Roberts explored the impact of World War I upon their respective Souths, Reynolds Price reflected on 9/11 through the prism of southern culture (The Good Priest’s Son, 2005). Southern literature offers innumerable examples of such returns to past events. African-American writers greatly contribute to the current face of southern literature and again they seem to be picturing the present with a backward glance that informs the present in rich and varied ways—they are, as Thadious M. Davis puts it, “reclaiming the South” by “both literally and imaginatively returning to the region and its past, assuming regional identification for self and group definition” (66). There are many more writers today voicing the South, as Michael P. Bibler shows in a 2016 section of PMLA 131.1 devoted to that specific region. Bibler’s affirmation that “exceptionalism would segregate the South from the nation, while pure anti-exceptionalism would make the South disappear completely” (154), raises numerous questions that strongly contrast with Zinn’s aforementioned take on the matter.

In order to understand the South, and tell about it, it is essential to look at it not as a separate entity but as part of a whole—Barbara Ladd has provided a survey of numerous views on the matter in a 2005 essay (evoking, among others, John Bell Henneman, Jay B. Hubbell and Louis D. Rubin). Keeping in mind the context in which any text or cultural object emerged from the South is indispensable for many obvious reasons. The two world wars and the many conflicts in which the United States were involved through the 20th century and the first decades of the 21st, the Great Depression and the Civil Right Movement certainly contributed, among other major events, to the appearance of new, sometimes contradictory voices, that kept multiplying and diversifying the facets of the South. According to Lewis P. Simpson, “the deepest truth about southern literary history may finally be discovered in the ‘intertextuality’ of white and black writing” (qtd. in Ladd 1629). The questions of race and gender are equally essential to grasp what the South is about but, as Ladd makes clear, re-evaluating works through the prism of earlier models and methods is not satisfying. There is always a risk of “echoing past concerns and past monologues—those defined by fear of change and difference” (Donaldson 665) that are exemplified in fiction by Faulkner’s Quentin Compson or Simms’ Captain Porgy. New tools have to be invented, together with new ways of looking at the South that will make it alive rather than stilted. Studies such as Patricia Yaeger’s Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women’s Writing, 1930-1990, is a particularly good example as it looks at marginal writings in relation to the canon but also elaborates on the concept of marginality and accounts for earlier limited (and limiting) readings.

New ways of looking at the South have appeared in recent years, gender and LGBT studies, food studies, ethnic approaches, urban/rural explorations, for example. Jay Watson suggests another path which could be extended to the field of nature writing: “if southern studies and environmental studies are to emerge from nostalgia and defeatism as reinvigorated and relevant disciplines, the two fields will need to learn from each other” (159). He also invites scholars to deepen “consideration of which pasts to claim and which forms of change to interrogate or contest in the field’s ongoing work of negotiating tradition” (159). Television and the movies present equally thought-provoking ideas on the South, making the region different from any other while questioning its forceful singularity. It could thus be argued, with Gina Caison and Amy Cluckey, that “the New South” is no longer a relevant label because “Future Souths” are emerging and shaping time as it unfolds. The purpose of Urszula Niewiadomska-Flis’ recent collection, Ex-Centric Souths: (Re)Imagining Southern Centers and Peripheries, is announced through a quotation from Barbara Ladd placed as an epigraph to the volume: “[Let’s] reimagine the or a South or multiple Souths to take full measure of the significance of alternative memories, histories, and modes of cultural expression.” In her introduction, “(Re)Imagined Souths,” Niewiadomska-Flis explains that the nature of her project is to “add a modest voice in ongoing attempts to chart new routes and to decenter the South in many ways in the hope of exploring Southern identity and multiple Souths” (13). She grounds her ideas in comments by various specialists including Larry Griffin, Robert Brinkmeyer, Michael Kreyling, Tara McPherson and Richard Gray while also considering the emergence of New Southern Studies that focuses more specifically on “minority literatures, search for transnational connectivity between the South and other global regions, and employ postcolonial conceptual models of theory” (16). Margins thus become central and help the contributors “interrogate the Southern imaginary and rescue it from fragmentation, reduction, misrepresentation, and distortion in the national imaginary” (21-22). It is our goal to pursue such a project and add another brick in the wall.

Most of the articles in this volume were first presented at the 2017 Southern Studies Forum which was held at Lille Catholic University in France. Many Southernists from the world over gathered on that occasion and we had the pleasure to welcome and listen to Elizabeth Cox and Ron Rash who kindly accepted to join us and present their work and relationship to the South. We want to thank Lille Catholic University for its generosity and Carme Manuel who showed early interest in publishing a collection of essays deriving from the conference papers. The initial contributions were expanded into fully-fledged articles, and expertised by specialists whom we also want to thank here.

The first part of this collection focuses on “Images of the South in Popular Culture and Literature”: it opens with late M. Thomas Inge’s presentation of Richard Corben’s graphic adaptation of Edgard Allan Poe’s specific brand of southern Gothic. While Hana Ulmanova and Suzane Joskova revisit the “white trash” mythology as exemplified by Dorothy’s Allison’s short story “River of Names,” Françoise Clary examines the intertwining of myth, Southern history and digital popular culture in Colson Whitehead’s 2001 novel John Henry Days. As for Jacques Pothier’s contribution, it focuses on some of the “beasts of the southern wild” that emerged in literature and movies after Hurricane Katrina.

The second part of the book is devoted to representations of “The Power of Place.” Elisabeth Lamothe explores Katherine Anne Porter’s Mexico through the notion of displacement. Suzanne Bray analyses Madeleine L’Engle’s vision of kinship in the urban South in her novel Ilsa (1946). Stéphanie Maerten examines Elizabeth Spencer’s depiction of New Orleans and its intense power of fascination, while Pearl Amelia McHaney offers an inspiring comparative study of the use of place in two novels by Toni Morrison, Home and Jazz, and two short stories by Eudora Welty, “Flowers for Marjorie” and “Music from Spain.” Amélie Moisy closes this section with a reflection on Edward P. Jones’s representations of D.C., in which the southern past keeps surfacing.

The collection’s third part revolves around “Memory and Identity.” Jadwiga Maszewska focuses on Peter Taylor’s art of storytelling as exhibited in two short stories, “A Spinster’s Tale” and “The Old Forest.” Whereas Youli Theodosiadou shows how Phyllis Alesia Perry’s 1998 novel Stigmata revisits slavery, Patrycja Kurjatto Renard compares how David Bradley’s The Chaneysville Incident (1981) and Octavia Butler’s Kindred (1979) both deal with the negotiation of family past(s). Frédérique Spill concludes this section with her reading of escape strategies in Ron Rash’s 2016 novel The Risen, a novel set in the course of the summer of love in Appalachia.

The fourth section centers on the question of “Racial Strife,” starting with Elizabeth Hayes Turner’s analysis of Juneteenth as “the celebration of a gaudy illusion.” Mark Newman examines the Mississippi Summer Project of 1964 through the eyes of a northern clergyman. Stéphanie Suchet devotes her attention to the representations of minorities in William Faulkner’s 1948 novel Intruder in the Dust. Finally, Susana Maria Jiménez Placer compares how the image of the mammy is revisited in Kathryn Stockett’s The Help (2009) and Harper Lee’s Go Set a Watchman (2015).

The fifth and last section presents various “Visions of the South.” Valeria Gennaro Lerda envisions early 20th century southern women’s clubs as forerunners of environmental reforms. While Marcel Arbeit proposes a study of the absurd in the South as exemplified by Flannery O’Connor’s writing, Susan V. Donaldson dwells on “the ghosts of Reconstruction” in Toni Morrison’s 1998, post Nobel Prize, novel Paradise. Ineke Jolink examines the “minimal maneuvers between dystopia and utopia” in two stories by Breece D’J Pancake, while Clara Juncker presents how painter William H. Johnson’s depiction of Denmark is colored by the American South.

This section also contains an unpublished article by late Simone Vauthier on the use of the supernatural in Reynolds Price’s Love and Work (1968) which was found in Price’s archives at Duke University. It is a great honor for us to have a chance to pay tribute to a great scholar who devoted much of her time, energy and passion to Southern culture.

We want to thank all contributors to this volume for their insightful contributions to the relentless vivacity of Southern Studies from different corners of the world. We dedicate this volume to M. Thomas Inge who passed away as we were putting this book together and to Richard Corben who had kindly agreed to let us use illustrations from his book before he, too, sadly passed away. May Tom’s work inspire many generations of Southernists to come, and his memory live on in the hearts of those who knew him and cherished his friendly presence.

Works Cited

Bibler, Michael P. “Introduction: Smash the Mason-Dixon! Or, Manifesting the Southern States.” PMLA 131.1 (January 2016): 153-56. Print.

Cash, W.J. The Mind of the South. 1941. Introduction by Bertram Wyatt-Brown. New York: Vintage, 1991. Print.

Caison, Gina and Amy Clukey. “Afterword: Future Souths—Emerging Voices in Southern Studies.” PMLA 131.1 (January 2016): 193-96. Print.

Davis, Thadious M. “Reclaiming the South.” Bridging Southern Cultures: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Ed. John Lowe. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 2005. 57-74. Print.

Donaldson, Susan V. “A Symposium: The Business of Inventing the South.” Mississippi Quarterly 52.4 (Fall 1999): 662-69. Print.

Eby, Margaret. South Toward Home: Travels in Southern Literature. New York: Norton, 2015. Print.

Hobson, Fred, ed. South to the Future: An American Region in the Twenty-First Century. Athens: The U of Georgia P, 2002. Print.

Humphreys, Josephine. “A Disappearing Subject Called the South.” Friendship and Sympathy: Communities of Southern Women Writers. Ed. Rosemary M. Magee. Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1992. 297-301. Print.

Ladd, Barbara. “Literary Studies: The Southern United States, 2005.” PMLA 120.5 (October 2005): 1628-39. Print.

Lowe, John Wharton. Introduction. The Future of Southern Letters. Eds. Jefferson Humphries and John Lowe. New York: Oxford UP, 1996. 3-19. Print.

Niewiadomska-Flis, Urszula, ed. Ex-Centric Souths: (Re)Imagining Southern Centers and Peripheries. València: Universitat de València Biblioteca Javier Coy d’estudis nord-americans, 2019. Print.

Rubin, Louis D. The Mockingbird in the Gumtree: A Literary Gallimaufry. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State UP, 1991. Print.

Shafer, Byron E. and Richard Johnson. The End of Southern Exceptionalism: Class, Race, and Partisan Change in the Postwar South. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2009. Print.

Tate, Allen. The Man of Letters in the Modern World: Selected Essays, 1928-1955. London: Meridian Books, 1957. Print.

Watson, Jay. “The Other Matter of the South.” PMLA 131.1 (January 2016): 157-61. Print.

Yaeger, Patricia. Dirt and Desire: Reconstructing Southern Women’s Writing, 1930-1990. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2000. Print.

Zinn, Howard. The Southern Mystique. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1970. Print.

Edgar Allan Poe, Richard Corben,and the Southern Gothic in the Graphic Narrative

M. Thomas Inge

Randolph-Macon College, Ashland, Virginia, United States

Raised and educated in Virginia, Edgar Allan Poe (1809-1849) considered himself a Southerner, even though he seldom wrote about the Southern experience in his stories and poems. Richard Corben (1940-2020), born and raised in the border-Southern state of Missouri, emerged as one of the most talented interpreters of Poe in the comic book or graphic narrative in late twentieth-century America.

Without Edgar Allan Poe and some of his fellow popular writers, there might not have been a comic book or a graphic novel. That is to say, in the early days of the comic book industry, desperate to meet the insistent and inevitable monthly publication deadlines, writers and artists turned for inspiration, or outright piracy, to the popular short fiction of such authors as O. Henry, Stephen Crane, Ambrose Bierce, or Guy de Maupassant. Before them, the nature and structure of the short story had been fully defined by Poe in his reviews and critical essays in the nineteenth century. Poe did not invent the short story, but he so successfully outlined what an effective piece of short fiction should be that everyone used his standards by which to measure their own work. Reading Poe was like taking a master class in writing fiction.

Little wonder then that the early pioneers of a new art form more frequently turned to Poe than any other author for source material and inspiration. It has been estimated that over 300 adaptations of Poe’s stories and poems have appeared in comic books and graphic novels from 1943 to the present. While nearly every major and most of the minor comic book authors and artists have turned to Poe at one time or another in their careers, only one has dedicated a major part of his life’s work to adapting his poems and tales—Richard Corben. Emerging from the underground comix movement in the 1960s, he quickly became a major force on the larger comic book scene with his work for Heavy Metal magazine and the Warren publications. Those who picked up copies of his early work like Den, Rowlf, or Fantagor, were immediately absorbed by the maturity and beauty of his style. Readers knew that they were in the presence of an extraordinary talent. Corben’s imagination pushed the boundaries of the visual possibilities of aesthetics in comic art in amazing new directions.

Beginning with his adaptations of Poe for Creepy, Eerie, and other Warren titles, especially the brilliantly rendered version of “The Raven” in Creepy No. 67 (December 1974), Corben has proven to be the most acute and creative interpreter of Poe in comics history. All of his comic book work, in fact, has been imbued with the same gothic sensibility and keen eye for the grotesque that possessed Poe himself. Thus, his alliance with Poe has been a fortuitous and productive one. Time and again Corben has turned, or returned, to his favorite poems and stories, each demonstrating an original vision, a new way to interpret or understand Poe’s themes. Corben’s latest Poe anthology, Spirits of the Dead, is a peak in their collaboration, a brilliant summing up of their relationship. It includes adaptations of five poems and nine tales, all written and drawn in splendid Corben-color, with expert lettering by Nate Piekos.

Adapting Poe’s poems provides a richer source of possibilities than one finds in adapting his stories. The poems typically describe an emotion, a feeling, an idea, or a state of mind. While a backstory or prior narrative is often implied, beyond that the artist is free to invent whatever seems suitable to the main theme, be it loneliness, desperation, grief, love, or the loss of a loved one. It was Poe who claimed that the most moving theme for a poem was the death of a beautiful woman. Very often, the poem interrogates the reader about the theme, a pattern followed by Corben in his version of “Alone,” which opens this collection. Corben sets the reader off balance by melding dream, nightmare, and reality into one, such that neither the narrator nor reader can tell the difference. It asks the question, do dreams really mean nothing or are they glimpses of a world beyond mortality and mutability?

Richard Corben, “Alone,” 14.

Generally, Corben does not address politics and themes of social justice in his adaptations, but they enter in two of the poems included here. “The City in the Sea” uses only the opening and closing lines of the poem to enclose a tale of a captain who has lost his entire cargo at sea. He washes up on a mysterious island populated by specters who put him on trial. When charged with crimes against humanity, he defends himself by claiming that nothing of value was lost on the ship, and its value was covered by insurance anyway. Then we learn that the cargo consisted mainly of thirty tons of African slaves, and the insensitive, bigoted captain is sent to Hell.

Richard Corben, “The City in the Sea,” 25.

In “The Sleeper,” Corben provides a concrete dramatic situation for a general poem about death. Justice comes to a man who has caused the murder of his wife and his mistress. Since the story seems to be set in New Orleans, and the characters appear to be free blacks of African descent, this adds a racial dimension to the story.

Richard Corben, “The Sleeper,” 29.

Perhaps his most imaginative recasting of a poem in Spirits of the Dead is Corben’s version of “The Conqueror Worm,” which appears to be set in the American West. Colonel Mann has murdered his wife and her lover in a cold-blooded execution in the desert. Two strange performers appear and offer to amuse him with a stage play the next evening. With grotesque puppets they perform a truncated version of Shakespeare’s Hamlet, which also parallels the double murders the Colonel committed the day before. The skulls of the victims infested with worms appear as a part of the performance, and the worms eventually consume everyone—audience, actors, and Colonel Mann. As the poem tells us, “The story is the tragedy ‘Man,’ and its hero the Conquerer Worm.” With its elaborate structure of a play within the narrative, Corben’s story is like a Shakespearian tour de force.

In both the poems and the stories, Corben borrows a narrative device from the classic EC horror comic book titles of the 1950s which had either the Old Witch, the Vault Keeper, or the Crypt Keeper introduce each story. Corben’s device is a character called Mag the Hag, who opens each story, concludes it, and sometimes takes part in the plot. She is an unsightly creature, sexually ambiguous, and given to rude interruptions. But her presence adds a layer of meaning to the proceedings through her ironic attitudes and sarcastic platitudes.

“Berenice,” Poe’s story of a lover’s obsession with his late beloved’s teeth, a tale not to be read before a visit with the dentist, becomes in Corben’s retelling a strange experiment in gender-bending narrative. Berenice, to all appearances, seems to be a man rather than a woman. This does not disturb the narrative mood, however, since the central character has lost all sense of time and reality anyway. As usual in Poe and Corben’s versions, dream, delusion, and reality are often indistinguishable. Although he is a very good writer, Corben cannot resist an all-too-easy quip at the end, “I guess it was a case of ‘a tooth for a tooth.’”

Richard Corben, “Berenice,” 50.

Poe’s best known and perhaps most popular story, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” has attracted nearly every major comic book artist for adaptation. Corben leads the reader into his version by several pages of mood setting imagery that place us in the presence of darkness and death. The narrator, here called Allan, after Poe’s middle name, finds that Usher is painting grotesque images of morbidity but working mainly on portraits of his sister, Madeline, with whom he is passionately in love. Borrowing elements from another Poe story, “The Oval Portrait,” just when Usher reaches the perfection he has been seeking in a portrait, Madeline drops dead, her soul apparently having passed into the painting. After days of mad delusion, Allan finds, of course, that Madeline has been buried alive, while he fights with Usher over possession of the portrait. The whole perverse and incestuous triangle tumbles into the tarn with the collapsing House of Usher. Like Ishmael, Allan alone survives to tell the story. While all of the elements of the original story are retained, Corben adds complexity and psychological power to the narrative by making explicit some things only hinted at in the story. As a tale well told with outstanding art that threatens to pull the reader into its bizarre world, this must be considered one of the finest adaptations of the story that we have. At 47 pages, it may well be the longest as well, but we value every single page as Corben unfolds the narrative slowly and wordlessly with primary emphasis on the visual rather than the verbal. Anyone reading the original after this adaptation is likely to find it informed by Corben’s vision in a kind of reverse influence.

Richard Corben, “The Fall of the House of Usher,” 71.

Corben’s version of another very popular story, “The Murders in the Rue Morgue,” is strongly grounded in the physical reality, the architecture, and the dress of 1840s Paris. He maintains the rudiments of the original story and succeeds, as did Poe, in keeping the reader in suspense about the identity of the murderer (most comics adapters have found this difficult). Both Auguste Dupin, and his friend Beluc, fall into patterns of behavior and modes of detection characteristic of their literary progeny, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, a tribute to their symbolic importance. Corben, however, has crafted a more original ending than Poe’s, by allowing for a turn of poetic justice in the conclusion, an improvement on the master tale teller himself.

“The Masque of the Red Death” is another frequently adapted story, yet Corben brings fresh ideas and eyes to the familiar plot about aristocrats attempting to escape the plague through isolation and revelry. Mag the Hag leads the reader into a site of devastation, while a spectral figure recites the first five stanzas of a poem from another story, “The Haunted Palace” from “The Fall of the House of Usher.” Although written for another context, the poem perfectly fits the events laid out by Corben in vivid color and compelling imagery. A socially relevant twist is added to the story by having the king spend the royal treasury on wanton pleasure rather than clean up the unhealthy conditions that caused the plague in the first place. Grotesque characters and beautifully designed panels and pages provide the disturbing experience that only a master comic artist can create.

Richard Corben, “The Masque of the Red Death,” 145.

Corben always uses the full page as an artistic unit and moves from an expanded beginning or splash page (in the mode of Will Eisner) to carefully constructed panels that relate to or express the psychological state of a character or the emotions intended for the reader. Everything in a Corben page is functional, and there are no empty artistic gestures to fill space. Every image, shadow, facial expression, piece of clothing, color, or sound contribute to an aesthetic experience that is profound and disturbing. Quite likely Poe would have loved these graphic versions of his work and recognized in Richard Corben a soulmate.

Richard Corben, drawing used for the cover of the hardcover edition,signed to M. Tom Inge.

Works Cited

Corben, Richard. Edgar Allan Poe’s Spirits of the Dead. 2014. Milwaukie: Dark Horse Books, 2019. Print.

______. “The Raven.” Creepy, No. 67, Warren Publications, 1974, unpaged. Print.

NOTE: An earlier version of this essay appeared as the introduction to Richard Corben’s Edgar Allan Poe’s Spirits of the Dead.

The illustrations appear courtesy of Richard Corben, InkWell Management, and Richard Corben’s estate.

The Vicious Circle: “White Trash” Mythologyin Dorothy Allison’s “River of Names”

Hana Ulmanová and Zuzana Josková

Charles University, Prague

The members of the Department of English and American Studies at Charles University in Prague first encountered Dorothy Allison’s short story “River of Names” in 1994, in The Vintage Book of Contemporary Short Stories (edited by Tobias Wolff and published by Random House). Nothing of the author or the story’s genesis (in 1974, it started as an outraged poem full of grief) was known, but it immediately struck us as a masterpiece; beginning with the perfect Gothic image, written in a rather minimalist language (both as to vocabulary and syntax) and yet full of postmodern questions concerning fiction and its status. It had a confessional quality, and yet it never crossed the divisions between the narrator and her lover, who happened to be physically in bed, intimately touching each other.

Within a year, it was taught in our Southern literature class, and in 1996, the first thesis devoted to Dorothy Allison’s life and works was finished. Diana Krausová, its author, was—like the other students—astonished that the characters never manage to escape poverty and are trapped in a vicious circle of violence. Why this is the case has often been discussed since. A conclusion was reached that in order to explain that phenomenon, a focus on Judith Butler’s argument that “sex and gender are tools in the perpetuation of acceptable practices” (23) would have to be established.

In the meantime, Zuzana Josková who wrote her thesis on Dorothy Allison’s works, relying on the theory of myth as presented by Roland Barthes, translated into Czech not only “River of Names,” but also Bastard out of Carolina. Since the term “white trash” that appears in the original is impossible to accurately capture in our native tongue, three different Czech words were used in the end; namely “póvl” (an archaic yet informal and pejorative word for the rough and uneducated), “špína” (literally “dirt,” denoting both the supposed physical and mental state of the underprivileged), and “spodina” (meaning those at the very bottom of the social ladder). Only then did the tricky position and multiple identities of the “white trash” fully reveal themselves.

I

“White trash” is “the most visible and marked form of whiteness” (Wray and Newitz 2). It oscillates between being a slur1 to a proud denomination of one’s origins (Hartigan 44). On the one hand, it is the subject of a growing body of academic work; on the other, a great number of people use it as a derogatory term—as the term “trash” means “social waste,” it suggests both degradation and shame (Wray and Newitz 4). Moreover, in the age of political correctness and official respect for ethnic diversity, it seems to be the only remaining fair game for put-down humor (Kirby 89). It is used here as an umbrella term which includes all other similar denominations such as poor whites, landless whites, rednecks, hillbillies, crackers, etc., understanding the fact that each of these labels has a slightly different referent with a specific history; this might potentially be dangerous to the argument since one of the most critical moments in the creation of a stereotype is the unification of diversity.2

“White trash” as a cultural concept unites numerous identity categories, and it is, therefore, imperative to subject it to a multilayered analysis; one which questions and attacks especially those aspects ascribed to “white trash” which have been quietly considered natural. In America’s cultural milieu shaped by the widespread belief in classlessness (Beaver 17), and the possibility of the acquisition of the American dream, “white trash” sounds like a pure literary oxymoron. It is a pregnant label referring predominantly to the never-ending cycle of poverty among white people living in the rural South,3 which is seen as un-American and alien. Nevertheless, it also carries inherent moral, biological, behavioral, and intellectual connotations. “White trash” people—read predominantly men, since in the “white trash“ discourse women have always been defined, and defined themselves, in terms of their relationship to men (Tracy 185)—are and have been stereotyped as lazy, shiftless, slothful, indolent, immoral, racist, overly sexually active and violent alcoholics. These connotations have remained virtually intact for about 200 years,4 allowing “white trash” to become a myth.

The most important aspect of a myth is that its content (in this case “white trash” people/bodies) always lies within a considerable distance from the recipient/creator of the myth. This distance is both literal and metaphorical. The myth is naturalized, grounded so deeply in people’s minds, that even upon coming face to face with its real content and history, the recipient rather turns to the mythical explanation. This naturalization is only possible because the content of the myth is always being deferred.

The analysis of the “white trash” myth following Roland Barthes’ concept of myth proves that “white trash” people/bodies are the empty signifiers of a specific myth, devoid of their history in order to preserve its mythic dimension and retain its function. In Mythologies, Barthes defines myth as something vague, “a mode of signification, a form” (109), a second-level sign made from a material which “has already been worked on” (110), in other words, simplified, subjected to stereotypical representations. What formed the “white trash” myth was primarily literature with its stereotypical depictions of rural Southern whites. All these representations have been emptied of their first level meaning before entering the myth as signifiers. Their signified is the concept of the myth which, according to Barthes “is confused, made of yielding, shapeless associations” (119) and holds together only due to its function. The most essential function of the “white trash” myth, according to Will D. Campbell lies in the fact that it provides a perfect scapegoat for America’s gravest sins (qtd. in Carr 9). This ultimate American “other” (Harkins 5) takes the blame for white racism, the very existence of poverty, and the inability to materialize the powerful myth of the American dream. It serves as a naming practice within a discourse of difference by which racial and class identities in the United States are maintained, and it is a concept used predominantly by the middle class in order to assure themselves of their superior status (Beaver 13). White trash thus serves as an example of “failed whiteness” (Beaver 15). It follows that “white trash” people pose a threat to the rest of the society—a threat that the “white trash” concept might disintegrate, and the sense of responsibility will shift to those who keep denying it.5 In other words, the “white trash” people act as a scapegoat in taking the blame for many of the failures and paradoxes that are inherent to American society and its dream.

“Myth transforms history into nature” (129), claims Barthes. It substitutes the linear relationship between the signifier and signified into a causal one (a natural cause replaces an individual impulse), and robs the signifier of its history. In order to denaturalize or deconstruct the myth, it is necessary to reveal the history of the signifier. In the “white trash” discourse, the signifier, or the infinite number of signifiers, are people, bodies. The naturalization of “white trash” signifiers meant not only that poor white Southerners were robbed of their history but also of their voice. “White trash” people have always been objectified and silenced precisely because of the danger they might want to narrate their side of the story, and thus undermine Southern master narratives. In this respect, “trashy” whites share the fate of all other groups (not only) in the United States. They were/are disenfranchised and oppressed based on various aspects of their identity—their race, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, class, opinion, religious beliefs, or anything else. The “white trash” myth thus mirrors the function of the master narrative of the colonizer. It renders the disenfranchised subjects as “other” and sustains in them the notion of natural inferiority.

Dorothy Allison is the embodiment of the myth’s empty signifier. Her work is one of the very few “white trash” signifiers which has managed to acquire a voice and be heard, and she is one of the even fewer writers who dared to make their “white trash” story the main focus of their narration; she writes from within the myth and intentionally seeks to shatter it. Allison primarily disrupts the myth by placing women’s stories and issues into the center of her writing. Her authorial identity is comprised of numerous aspects ranging from that of a “white trash” girl to that of a writer, a lesbian, a fighter for the freedom of one’s sexual appetite, a rape victim, a mother, a political activist, and many more. This multilayered perspective is always connected to the questions of gender and sexuality (and, to a lesser degree, class). A close reading of Allison’s short story “River of Names” and an additional recourse to her memoir Two or Three Things I Know for Sure will show how the numerous issues in her work intermingle and conflate, thereby producing a distinct identity, a distinct body, a unique text carrying numerous functions. Focusing on the “white trash” myth, it is the “white trash” aspect of Allison’s writings which will be given the most significant attention.

Allison attempts to denaturalize the “white trash” myth and therefore sets her text in opposition to the mythical text by the acts of writing and narrating personal stories from a “white trash” subject position. However, her attempt to shatter the myth might have, paradoxically (but within the logic of the myth), only reinforced it. This paradox can be clearly seen if we consider what Barthes has to say about the difficulty of deconstructing a myth from the inside: “[I]t is extremely difficult to vanquish myth from the inside: for the very effort one makes in order to escape its strangle hold becomes in its turn the prey of myth” (135).

According to Barthes, when entering the myth, the signifier has to be simplified, emptied of its true meaning, robbed of its history. Only under these circumstances is the signifier sufficiently pliant, and capable of expressing the meanings demanded by the myth. Within the “white trash” myth, this simplification has been achieved through the formation of “white trash” stereotypes predominantly in literature and the press. They were either despicable or pitiable, either threatening or comic, either dull or cunning. This rigid dichotomy in the literary portrayal of “white trash” reflected their boundary existence. It advocated the impenetrable social division putting forth the less-human character of poor whites since no real human beings behave in accordance with the schematic and stereotypic portrayal.

The most frequent “white trash” literary stereotypes have been, as alluded to earlier, the following: immorality, drunkenness, laziness, beggary, vagrancy, poverty, aggression, dullness, animosity, emotional simplicity bordering on idiocy, mental and physical retardation, unconditional hatred, filthiness, malnutrition, etc. Some of these stereotypes relate equally to men and women, although it is the men who are associated with them in the first place since masculinity is seen as a master narrative.

An important moment in the creation of the “white trash” myth is its widespread representation in photography. The importance of photography in national journals and magazines from that period was considerable. In order to collect material for their social policies between 1935 and 1943,6 the government sent twenty-four predominantly Northern photographers to document Southern poverty (Kidd 110) and supply, in the editors’ words, “archetypal representations” of the American poor (116). The textual stereotypes suddenly met with the photographs of their protagonists—the word was united with the image, multiplying the power of the myth. To contextualize this development, we can compare it with Barthes’ perception that the complete sign, the complete “myth” is the “associative total of a concept and an image” (114) since “[p]ictures, to be sure, are more imperative than writing, they impose meaning at one stroke, without analyzing or diluting it” (110).7

The majority of the actual journalistic descriptions was less bound to provoke laughter than the literary ones, provided by writers like Erskine Caldwell.8 Here, the most representative publication is Walker Evans’ and James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise the Famous Men from 1939; originally meant to appear in a newspaper, this project ended up being a book. Furthermore, while adopting quite a few stereotypical approaches toward the poor whites, the authors also attempted to re-shape the “white trash” myth. They offered a romanticized version of poor whites, as they focused on stressing the concept of “human divinity” (Agee and Evans xiv) and the spiritual richness of poverty. Thus, they bordered on celebrating poverty, and created the “worthy poor,” while invoking further contempt for the despicable “white trash” and their presupposed immorality. At this point, the myth of the “good poor” was born.

II

Allison leads a continuous dialogue with the myth, inside and outside of textual grounds; she does not restrict her performance solely to writing as she fears the postmodern reduction of her work to pure textuality (Griffin 145). She enhances her writing by publicly speaking about her life experience and in this way, creates an additional context for her work. Within her myth-defying project, she embodies both the real poor white Southern girl and the archetypal image of what Barthes could have called “white trashiness.” Such a complex situation echoes Barthes’ claim about the relationship of the myth’s concept (“white trash” signifier) towards its former meaning (“white trash” body): “[t]he form does not suppress the meaning, it only impoverishes it, it puts it at a distance, it holds it at one’s disposal… . [T]he meaning loses its value, but keeps its life, from which the form of the myth will draw its nourishment” (118). In other words, the myth is nourished continuously and re-formed by reality, constantly evolving but never really changing.

Allison’s characters represent the simplified concept of the myth as well as its erased meaning. They are the products of the myth as well as the instruments of its deconstruction. They are created by a self-proclaimed “white trash” author, who thus acknowledges the existence of the “white trash” myth, yet fights against its negative impact on “white trash” bodies. In her dialogue with the “white trash” myth, Allison simultaneously de- and re-constructs the myth, allowing the disassembled parts to transgress its boundaries and take on a life of their own. Allison intends to show the linear development in the history of her characters which the myth has naturalized as simple and knowledgeable facts. Her fighting strategy is to shake the foundations of these facts and show the audience her truth—real people with all their flaws. In Skin: Talking about Sex, Class and Literature, Allison writes: “My people were not remarkable. We were ordinary, but even so we were mythical. We were the they everyone talks about—the ungrateful poor… . I understood that we were the bad poor …” (13, 18). Within the structure of the narrative, she is the author, the subject, and the audience, writing for and about herself. Allison stands in the center, unifying all participants of the text, thus defying one of the major prerequisites of the myth, which is unconditional objectification, and prescribing definite meanings to signs regardless of their context.

Her work being largely autobiographical, Allison writes mainly about herself. This self-referentiality gives her texts the most persuasive argument through which the author can shatter the myth. Through her use of individual speech, Allison refuses to serve as an icon, as a body which lets itself be written over, filled by outside interpretations. By performing her unique subjectivity, she drags the empty signifier down to the first level of Barthes’ myth-diagram (115)—to the level of language and meaning.9

Allison makes use of a vast number of Southern issues. The focus on the South as a unique region, the nature and importance of female story-telling, the Southern grotesque, and Puritan work ethics are all issues that she deals with in her work. In recent academic assessments,10 she is seen as much of a writer as a political public persona, a transgressive sadomasochist lesbian, a trauma patient, or an incest survivor, and her work is thus judged accordingly—as a literary text, a manifesto, or a rape victim’s confession. Therefore, it is possible to analyze her work from a literary perspective, while not excluding the possibility of her texts to function otherwise and see her texts as an integral part of social power structures.

In all her works, Allison maps the porous borders between myth and reality, fact and fiction, truth and lie, and investigates the complicated nature of such emotions as love and hate, or pride and shame. Her texts prove that these categories do not form binary oppositions and that such strict divisions only encourage the simplification which leads to the formation of any myth. Allison’s short story “River of Names,” opening her collection Trash, reveals what the myth never considers the invisible responses of the “white trash” bodies, such as inner shame. The narrator refuses her “white trash” identity, and she consequently cuts herself off from the positive elements which have shaped her life—her family, her history—and loses herself in self-denial. She struggles to create a new self, but cannot rely upon any stable and positive elements.

The narrator of “River of Names” hides her “white trash” background from her middle-class lover whose grandmother “always smelled of dill bread and vanilla” (Trash 13). Entering the dangerous field of the narrator’s childhood memories, the narrator’s lover sincerely inquires:

“What did your grandmother smell like?”

I lie to her the way I always do, a lie stolen from a book. “Like lavender,” stomach churning over the memory of sour sweat and snuff. (Trash 13)

The narrator lies not only about her grandmother but from a general point of view also about her childhood, and thus about herself. The memory of “sour sweat and snuff” represents her personal history as well as the “white trash” myth. The narrator’s grandmother did not fit the only acceptable signifier of a grandmother, the standardized middle-class image of a spick-and-span house with a gentle laborious lady in it. On the contrary, “sour sweat and snuff” implies roughness, manliness, boldness, and self-indulgence—characteristics which are more often associated with grown men. It is crucial to note the alliteration that Allison uses as it describes the drab and repetitive nature of the real-life that many of the “white trash” people have to endure. Moreover, “stomach churning” signals a physical resistance to the memory, a denial which is rooted deep inside the narrator’s body. What comes into the foreground is the tension between the safe and socially acceptable image of a grandmother, and the potentially dangerous but more authentic image that the narrator recollects. However, even this authentically experienced portrayal of the grandmother corresponds with the “white trash” myth through allusions to dinginess, laziness, and overall unacceptability of her image.

The narrator substitutes her history with a “lie stolen from a book” which indicates the direction in which she is heading to construct her new identity—she attempts to create herself out of fiction. To smell like “lavender” is a common simile devoid of any type of originality—the narrator wants to construct an image which will be easily believable and readily accepted by her lover, an image already existing in her mind. The narrator continues: “I realize I do not really know what lavender smells like, and I am for a moment afraid she will ask something else, some question that will betray me” (Trash 13). The text thus brings forward the notion that one can never wholly re-create oneself based on partial self-denial. The “white trash” subject is pressured to deny her whole history because its every aspect is infected by the mythical interpretation. In other words, the narrator of “River of Names” is unable to construct her identity freely regardless of any mythical paradigms. Constrained by her resistance to the “white trash” myth, she displays a tendency to always perceive the world through a filter of some myth, be it the fairytale myth of the middle-class or the acceptable myth of the “good poor.” This compromise comes closest to social acceptability while still retaining a fraction of authenticity. However, even this myth brings her no comfort and is unable to accommodate her body.11

Consequently, the only possibility to resist self-hatred and lifelong hopelessness is to resist all mythical simplifications and accept every/one’s flawed humanity. The text thus suggests that seeing a particular body behind the mythical signifiers weakens the effect of the myth. Mirroring the process of self-denial, the author has to leave the mythical battleground and re-enter her own body as a unique individual. In order to accept one’s feelings, it is necessary to separate them from those internalized by myth, to uncover the love concealed by hate, to repair the emotional damage caused to the “white trash” bodies by the myth: “Some of that stuff is true. But … I had to find a way to … show you those people as larger than the contemptible myth. And show you why those men drink, why those women hate themselves … Show you human beings instead of fold-ups, mean, cardboard caricatures” (Hollinbaugh 16).

The narrator of “River of Names” occasionally takes a stubbornly direct look at the way her family shaped her life. Although hate, anger or grief are not thematized, they protrude through the barrenness of the story. A poignant example of this is the narrator’s relative, Jack: “Caught at eighteen and sent to prison, Jack came back seven years later blank-faced, understanding nothing. He married a quiet girl from out of town, had three babies in four years. Then Jack came home one night from the textile mill, carrying one of those big handles off the high-speed spindle machine. He used it to beat them all to death and went back to work in the morning” (Trash 19). Jack’s life-story is told in a detached voice, refraining from judgement, and as part of a list, which has to do with numbers, or, as the author herself says in an interview with Robert Birnbaum, “logarithms” (“Author Interview”). The lack of articulate sound in Jack’s whole life (except for different screams or strange laughter) suggests hopelessness; stifling silence (even more dangerous and burdening) covers up eight years of Jack’s life in jail, and yet is bursting with meanings.

It is precisely the breaking of the destructive silence, which represents the last step of the “white trash” subject in his/her conscious resistance to internalize the myth. This process is the main issue in “River of Names” where the narrator recollects the frightful memories of her “white trash” childhood in an inner voice switching into the outer one only when she talks to her lover and tells “funny stories” or “lies,” as her inability to talk to her lover honestly is presented on nearly every page. Simultaneously, she fights the physical impulse to tell her the true story:

I open my mouth, close it, can’t speak….

I would like to turn around, talk to her, tell her… “I’ve got a dust river in my head, a river of names endlessly repeating. That dirty water rises in me, all those children screaming out their lives in my memory, and I become someone else, someone I have tried so hard not to be.”

But I don’t say anything, and I know, … that by not speaking I am condemning us … (Trash 20-21)

The strongest motivation in articulating her “white trash” history is the need to make peace with herself, to let the river of names flow out of her body. The act of revealing the truth about her family is not an act of denunciation or accusation; on the contrary, it is an act of purification saving the narrator from becoming someone she has tried so much not to be—another victim of the suffocating and harmful silence.

To reiterate and further explicate a point we have thus tried to arrive at, it becomes clear that in order to resist the “white trash” myth, one must step out of the mythical battleground, which might also mean to leave the community. The narrator is the first one in the family who has succeeded in that (and as an escapee is most probably seen as voicing something that should remain untold), while the failures of those who tried to escape are passed down in the family along with their shame only to prove that any attempt to resist the “white trash” myth will prove futile; this further isolates the family and reinforces the mythical spell. Furthermore, the failures provide an alibi for “white trash” people’s apathy and passivity. Such complex discouragement illustrates the internalization of the myth.

To metaphorically illustrate the dangers of a direct fight against the “white trash” myth (albeit an inherently gendered one), the narrator in “River of Names” mentions an episode when one of her boy-cousins tried to teach her and her girl-cousin to wrestle:

[H]is hand flashed at my face. I threw myself back into the dirt, lay still… . She wrapped her hands around her head, curled over so her knees were up against her throat… . Her teeth were chattering but she held herself still …

He walked away. Very slowly we stood up, embarrassed, looked at each other. We knew.

If you fight back, they kill you. (Trash 17)

This passage shows the difficulty of any physical resistance as the two girls are too petrified by their lack of self-respect, which is grounded in the unbreakable cycle of destruction and self-destruction they witnessed throughout their lives, to even consider the possibility that they can break free from it.

While posing the question of whether it is more effective to fight the myth on fictional or factual grounds, it becomes evident that the answer will not be simple. One of the reasons this might be a difficult task is the unclear boundary between the narrator’s voice in “River of Names” and Dorothy Allison. The true backdrop behind the stories unquestionably strengthens their impact on the audience, and the coherency between Allison’s autobiographical text and her short story is undoubtedly another factor to take into account. However, as the above-quoted excerpts show, the author makes ample use of pure literary techniques (such as juxtaposition, alliteration or repetition), augmenting the content of the story by subtle allusions and metaphors. The central one is that of a river: possibly the river of consciousness, or, as stated earlier, a purifying element flowing freely, constantly changing and moving, and carrying—instead of a mass of assaulted bodies—all the names to be either forgotten or rather remembered. Furthermore, we should question the reliability of the narrator of “River of Names” precisely because of the fragile boundary between the mythical and the authentic. Concerning the myth, the short story could be seen as reinforcing it since, in fiction, all protagonists function as signifiers separated from the reader by a wall of make-believe.

Thus, in answer to the question whether it is possible to shatter the myth from within, Allison’s text suggests no more that it is impossible to do so from the outside. Contrary to a “white trash” body the outside recipient of the myth can never distinguish between the purely mythical, and the personal. Simultaneously, deconstructing the myth within one’s own body does not necessarily lead to deconstructing any myth as such, since myths are not limited to individuals but exist in communities.

III

The “white trash” myth is a narrative pertinent solely to the United States. As has been said in the first section, this narrative marks various persons/bodies as “others”—it imposes upon them the notion of a shared and uniform identity, it deprives them of subject positions and silences them with a language that ignores their life (and) experiences. Consequently, the humanity of these “other” bodies is, as Sidonie Smith pointed out, “opaque” (435), and if those bodies wish to narrate their stories, they have to rely on the power of ex-centric narration.12 That is to say a narration with autobiographical elements which attacks any general master narrative, a personal narrative shaped in relation to or in a dialogue with (or even explicitly in opposition to) the prevailing narrative. In this respect, Allison is addressing these issues with an understandably higher degree of explicitness in her memoir Two or Three Things I Know for Sure.

Here, the decisive shift in her narratives is that she assumes the position of the subject (author): “I am a storyteller” (Two or Three Things