2,99 €

Mehr erfahren.

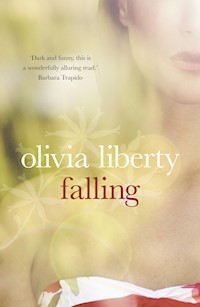

- Herausgeber: Atlantic Books

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Imogen Green is gone. Her favourite underwear is not in her drawer, her sexy summer dress no longer hangs in the wardrobe and her passport is not in the bureau. She has left her cat, her garden and her boyfriend, Toby Doubt. As Imogen's departure sinks in, Toby sets out to discover what could have driven his lover away. But her disappearance just doesn't add up. Surely, deep down, Toby knows where Imogen's gone and if she'll be back. This love story with a heart-breaking twist leaves Toby wondering whether there is anyone left to catch him as he falls.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2011

Ähnliche

falling

Olivia Liberty is a freelance journalist. This is her first novel.

‘This moving, funny first novel explores themes of change and loss, within the framework of an eccentric London comedy.’ Kate Saunders, The Times

‘Olivia Liberty’s tragicomic novel shows a good ear for dialogue and an unusual relish for sordid detail… the premise of the plot is an ingenious one and the ending has a haunting resonance.’ Anthony Gardner, Mail on Sunday

‘This story will leave you bruised and shell-shocked... How this novel manages to encompass the laugh-out-loud-funny life of an “everyday” London estate agent... while telling the tale of a man whose life is slowly unravelling is a mystery. But a mystery you will very much enjoy solving.’ Grove Magazine

‘An elegant debut... Great black comedy.’ Elle

‘Blackly funny… a weepie.’ First

‘A stunning debut in the style of Lesley Glaister and Julie Myerson – you will definitely be hearing more about Olivia Liberty.’ Robert Gwyn Palmer, Westside

‘Liberty has a writer’s knack for observing and recording the everyday marvels, oddities and epiphanies London offers up… Her first novel is a study of personal disintegration in which black comedy collides with surreal adventure and moments of genuine poignancy.’ Laura Tennant, First Post

falling

Olivia Liberty

First published in Great Britain in trade paperback in 2007 by Atlantic Books, an imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd.

This paperback edition published in 2007 by Atlantic Books. Copyright © Olivia Liberty 2007

The moral right of Olivia Liberty to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities, is entirely coincidental.

Every effort has been made to trace or contact all copyright-holders. The publishers will be pleased to make good any omissions or rectify any mistakes brought to their attention at the earliest opportunity.

‘Pearl’s A Singer’: words and music by Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Ralph Dino and Mike Sembello. Copyright 1974/1977, Jerry Leiber Music and Mike Stoller Music copyright renewed – all rights reserved – lyrics reproduced by kind permission of Carlin Music Corporation, London, NW1 8BD.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84354 608 5

eBook ISBN 978 0 85789 565 3

Printed in Great Britain

Atlantic Books An imprint of Grove Atlantic Ltd Ormond House 26–27 Boswell Street London WC1N 3JZ

Table of Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Acknowledgements

For my parents

one

The door slammed behind Toby Doubt. There was no sign of Howard so Toby stood for a moment on the step allowing his eyes to adjust to the day. He’d never noticed before that the step was worn, as though a great number of people had passed through here over the years. He’d certainly been through this door often enough – once, twice, sometimes three times – every day, for the three years they’d lived here. Sometimes with Imogen – ‘do you have your keys?’ – sometimes with Howard, once with a police officer. But mostly he’d done it alone, in the morning, late for work, long after Imogen had left for school.

However, this was the first time, as far as he could remember, that he’d done it traumatized. He examined the hedge: it glittered with debris. A McDonald’s milkshake thrust its straw into the sky, below it a green Carlsberg can glinted and a red and yellow Happy Meal. Further into the depths lodged the twist of a gold cigarette box, a brown glass bottle – cough mixture? – a yellow crisp bag, a bottle stained with the remains of something blue. Happy Meal, fags, cough mixture, anti-freeze. The key was to put these things in the right order. At the bottom of the hedge, beneath the blackened foliage of last year’s growth, stood a white polystyrene cup with a clean bite taken from the rim: a nice cappuccino to finish up. If the hedge hadn’t represented a certain sourness in his relationship – ‘Toby, I’ve been asking you for a week, please clear the front garden’ – he might have enjoyed the razzle dazzle of this morning’s display.

He picked up the briefcase which stood between his boots, the gate swung closed behind him and he crossed between cars to join the Monday morning work force blazing a trail along the pavement towards the station. The plants growing out of the wall quivered and the patina beneath the bench shone like Marmite. Below him a train clattered south. Money to be made. Money to be made. It thundered into the tunnel. There’s money to be made!

He joined the queue which stood impatient on the pavement outside ‘Steve’s Nest’. Ahead of him and above the chug of traffic a man in a pale suit was speaking into his phone: ‘And that, Sue, is why…’ he turned to look at Toby, white – toothpaste? – crusting the corner of his mouth, ‘she’s packed her bags and gone over to the other side.’ Toby’s thoughts turned to Imogen and to her bag, packed and zipped on the red carpet in the hallway. From there they moved to his chest where something cold and sharp lodged in his windpipe. It felt like a large silver whistle stuck in sideways.

Beyond the smeared glass and trays bearing tuna with sweetcorn and neon chicken tikka, Steve, his narrow back looped, was buttering toast. There was no sign of the Bulgarian girl who made the cappuccinos, smiled and told the customers ‘nice day’. Beyond Steve, coffee dribbled into a paper cup which rolled on its side. The counter was scattered with lids, empty milk cartons and dirty cutlery. Something clattered to the floor. The Nest was in disarray. Steve twirled the corners of a paper bag, handed it to the wrong customer, he dropped coins, turned to the cappuccino machine, splashed milk, fitted a lid, sprayed his shirt and wiped his nose on his sleeve.

‘Large cappuccino, one sugar, two toast granary with Marmite.’ The man in the pale suit ordered his breakfast. Imogen hated Marmite.

‘Butter?’ enquired Steve, a perfect button of frothed milk between his red-rimmed eyes. Steve turned back from the toaster and brushed his hands together. Two of his fingers appeared to be stuck in the same digit of his blue rubber glove. ‘Next?’ Steve turned his attention to Toby. He looked like he might have been crying.

‘Large cappuccino, one sugar, two granary toast with Marmite please.’

‘Butter?’ Steve brandished a knife which dripped with yellow and sniffed sharply. He had almost certainly been crying: the underside of his nose glistened.

While the man buttered, Toby wondered whether perhaps there was something, after all, in what Imogen had said: ‘I’m telling you,’ round eyes ice blue, chin raised, muddy hands emphatic. ‘Steve asked the Bulgarian girl to marry him. She told him she needed two months to think about it.’ Perhaps the two months were up and the girl had declined his offer. That had been known to happen.

Toby stood on the platform at Kentish Town, his back pressed against the warm brick wall. The toast was in his pocket and the cappuccino in his hand. Two trains clattered one after the other through the station and into the tunnel. Both were packed with standing, moon-faced commuters shuttled in from Luton and St Albans. As each train passed Toby felt its gravitational pull and he pressed his back further into the wall until he could count the indents where the cement held the bricks together. He turned to look at the bridge and the houses above it.

Number 3 Frederick Street stood high above the platform against the clear blue sky. It needed painting. Number 5, belonging to the dentist’s wife, was whiter than sugar and Number 1, on the other side, was blue and clean as the sky itself. Number 3 let down the terrace. The wire from the television aerial hung loose across the front and each of its three windows stared out dully through a cataract of grime. Toby wondered if a word existed to describe its colour. Nicotine? Dust? It was a non-colour related somehow to grey. He scanned each window and wondered if Imogen could be in the garden. Perhaps he had merely missed her – an oversight – as she crouched fiddling amongst her burgeoning lettuces before going off to school.

The top of a bobbing head appeared above the wall. In front of the house it disappeared to cross the road and make its way through the gate and up the path to the front door. He would recognize the top of that head anywhere: it was Howard.

A train pulled into the station. It slowed and stopped. There was a collective surge and Toby, hot in his suit, joined the straggle-end of the commuters knotting at the train’s doorway. No one got off. He cast a glance over his shoulder. The house was looking beyond him towards the City above which the NatWest Tower fingered the sky. Imogen wasn’t in the garden. The house knew it and Toby knew it.

The doors swept closed and the train dragged out of the station. The carriage laboured under the silence of breath and the mass of clean, hot people with a week’s work ahead of them. NEWS BULLETIN declared a newspaper inches from Toby’s face: A woman, 30, was decapitated when she leant out of a train window as it entered a tunnel in Kent. What kind of bulletin was that? What kind of a woman got decapitated?

‘Well, put it this way, Mark,’ a moustached man shouted into his phone above the roar of the clattering silence. ‘It could not have happened to a nicer person!’ Toby rubbed the toe of his brown Blundstone boot against his calf and wondered again what had caused the heart-shaped mark the size of twopence. It was dark like oil, black like blood.

At Farringdon, Toby got off. The platform was infused with soft green light filtered through a roof of arched glass – a serene greenhouse subterranea humming with the meaty whirr of pigeon wings. He sat on a bench. Imogen, Imogen what have you done? You’ve ripped out my heart and you’ve gone on the run.

He leant back against the bench and loosened his tie. It constrained his neck and made him more aware of the angular obstruction in his chest. Where the tie had come from he’d no idea. As far as he knew, he’d never owned a tie. It had appeared this morning, milk pink like a dog’s tongue, on a coathanger in the wardrobe between the suit and Imogen’s mother’s fur coat. He’d worn the suit just once six months ago on 27 December. He’d bought it that same morning on Regent Street in the first day of the sale while Imogen waited on a double yellow line in her mother’s Peugeot. She’d been complaining all morning that the car was full of hair – dog hair and her mother’s hair – and that she couldn’t breathe for swirling skin particles and hair strands. They were on their way to Imogen’s mother’s funeral and they were late because of Imogen’s sudden urge for sex as he struggled with his memory to locate the socks he’d been wearing yesterday. ‘Forget the stupid socks, Toby,’ Imogen had said as she writhed on the bed and sank her teeth into the mattress. And when Toby came out of the crowded shop to cross the busy road to ask her if a grey suit would be alright, unusually for Imogen, she lost her temper: ‘For Christ’s sake, Toby, just buy the frigging suit.’

The toast in his pocket was uncomfortably warm. He brought it out and a pigeon landed at his feet. Another arrived. The margarine had made the paper transparent and it reminded him of the lavatory paper with which his mother equipped the bathroom when he was a child. He returned the package to his pocket. The pigeons strutted in circles of disappointment down the platform and away from the bench.

It was hot on the Circle Line and through his trousers Toby felt the seat’s upholstery prick the back of his thighs. It was hotter still at South Kensington and by the time he emerged into sunlight, his shirt was entirely stuck to his back. The pavement glittered malevolently. It was, considering the fact that it was before 9 a.m. on 7 June (a date barely beyond spring) unseasonably hot. He stopped in the shade of a building to lift a knee on which to rest the briefcase given to him by Aunt Mercy on the occasion of his leaving school. ‘Don’t know if you’ve any use for this,’ Aunt Mercy sniffing and lifting it up as though she had no idea what it was for. ‘It used to be my father’s.’ Today, thirteen years later, it was being used for the first time. Shiny catches sprang open to reveal a red satin interior, stained in one corner with a brown blot. Something to do with Aunt Mercy’s father. The flouncy pockets were empty. What kind of a businessman came armed without accoutrements?

The letter was in the breast pocket of his suit. White and folded into thirds, it was soft from handling. He unfolded it. MILSON, RANGE & RAFTER appeared in royal blue print across the top of the page above 33 HARRINGTON GARDENS, SW7 1HP. ‘Imo’ it read. Imo? Imogen, Imo? Toby didn’t think so. In slanting hand the letter continued:

Just ran into the Colonel outside William Hill in South Ken. Did’nt know he was a betting man? He gave me shocking news. Said U R getting married. U sure babe? He gave me your adress and told me to write. Don’t do it. Marry me. Or at least let’s do lunch. First Love is the only True Love. U know it makes sense. Gideon Chancelight (Ur 1st Love!)

Toby refolded the letter and, returning it to his pocket, marvelled not for the first time at the spelling. Gideon Chancelight, First Love, was entirely illiterate. He had discovered the letter, dated 28 April, yesterday in the rosewood roll-top desk amongst gas bills and council tax books and a postcard from Sara in St Moritz. Yes, it was virtually incoherent, however it had shed some light on a problem which had hitherto laboured entirely in darkness.

Toby passed odd numbers on Harrington Gardens – 13, 17, 19, a car shop featuring three shiny BMWs trapped behind glass, 27, 29 and then Milson, Range & Rafter. An art gallery, a second-hand book shop, a riding stable. He had even been willing to consider a bookmaker, but an estate agent? Never. Who ever ran off with an estate agent? The windows were tiled with particulars: Roof Garden; Staff Accommodation; Swimming Pool. Sold. He followed the glass front round a corner and on to a narrow street which doubled back on to Harrington Gardens. Decorated with bright awnings, shop signs swung amongst trees lush with growth; the street looked French. An old man in a suit fidgeted under a striped canopy outside a delicatessen. Drawing on a cigarette, he was preoccupied with neatening the kerb stones. He tapped at them gently with the side of his shoe. Tap, tap. Tap, tap.

Toby pushed open the glass door. A buzz announced his arrival and the door swung shut behind him. A girl, blonde and pink behind a bowl of white tulips, was on the phone. She acknowledged Toby by turning away. With her free hand she pulled closed the neck of her pink cardigan.

‘How bad is that? It was like four times, I swear to you. It was once in the middle of lunch, no it was like twice in the middle of lunch. We’d just sat down and I’m like, hello? That is so not normal. So it was like once before we went in…’

Toby coughed and felt the knot of his tie. The girl frowned and turned farther from him. ‘Oh yeah, that’s right because I remember I’d just gone “Mum, Dad…” and immediately he was like… right, yeah but… Yes. I know all that…’

The office was narrow, a glass corridor camping on the pavement. Four cramped desks were arranged bus-style, one behind the other, against the window. The fifth desk, where the girl sat, faced the door. The office had the veneer of plush respectability: fashionable natural flooring, classical desks, a bookcase, framed photographs of white stucco mansions, yet there was something here that suggested impermanence, a certain theatricality, as though the whole thing could disappear tomorrow. And it wasn’t, as Toby had first thought, deserted. In the recesses where the window stopped and darkness encroached sat a monolith of a man. Head in hands he appeared to be asleep at the desk he dwarfed. Gideon Chancelight worn out by Imogen’s nocturnal demands. Toby stared but the monster didn’t stir.

‘And I’m like “Yeah, well, whatever.” And my Dad is like…’ the girl opened her mouth to smooth something shiny on to her lips. Round and round went the pink finger. ‘“Er, Daisy, who is this person?” And I’m like “Well, er, look Dad…”’ Under the glass desk the girl’s thighs were ripe peach-gold. They were solid and smooth and the fine down that covered them glistened in the sunlight. They were netballer’s thighs. As though sensing Toby’s gaze, the girl pressed them tightly together. Goal shooter’s thighs. Where they met ripe flesh dimpled nicely. Panting, breathless, blonde pony tail swishing, a pleated white skirt flaps above thick gym knickers as the girl stands, legs together, to score.

Behind Toby the door buzzed and the girl jabbed a biro in his direction. If Imogen had run off with an estate agent, why shouldn’t he? His heart shrivelled under sharp white pain.

The old man who had been outside neatening the pavement wiped small and shiny shoes carefully on the doormat. He looked up and smiled. ‘Good morning, sir, and what can we do you for?’

The thin fabric of the man’s suit hung loosely from his frame. His soft face was cream-cheese-pale apart from his nose which was red with blood as though he’d been hung upside down. He looked in need of some ‘R & R’ as Imogen might say. He cocked his head and raised an eyebrow. ‘Lettings or sales?’

Toby pulled the letter from his breast pocket and considered the direct approach: ‘I am here to enquire after my girlfriend, Imogen Green. Someone at this address’ – a glance showed the villain still asleep – ‘one Gideon Chancelight has been writing her inappropriate letters and I’m here to find out more.’ It didn’t sound right. Alternatively there was the Squire’s approach: ‘Bring on the sodomized son of a bitch. I’ll slit his weaselled throat.’ That didn’t seem appropriate either, here in South Kensington. And anyway the old man looked too frail to withstand such an assault. And the monster? Too large an adversary. Toby cleared his throat.

The man’s frown dispersed. ‘Gotcha.’ A hooked finger clawed the air. He looked Toby down then up and a deep chuckle turned into a phlegmy cough. When he’d recovered: ‘It is 9 a.m. on Monday morning and in front of me stands a young man: suit, briefcase, his whole future ahead of him. They don’t call me Clouseau for nothing.’ He held out his hand. ‘In fact they don’t call me Clouseau at all. Nigel Harmsworth-Mallett, lettings.’

‘Toby Doubt,’ said Toby putting his hand in the man’s paper dry one.

‘We spoke on the phone,’ he continued. ‘James? John? Wagtail isn’t it?’ The old man let the names hang in the air, eyes yellowed and watery. He looked away for inspiration. None came and he turned back. ‘Nigel Harmsworth-Mallett, lettings. Welcome, well, well.’

‘Toby Doubt,’ Toby repeated.

‘Dote?’ The man frowned. ‘Well, well, for some reason I was under the impression that you would be descending on us on Tuesday. Ours is not to reason why, well… no matter, the powers that be and all that. Bit of a madhouse here what with all this rain.’ He indicated the world beyond the glass, as blue and unconfused as eternity. ‘Leaks, rats. An infestation of rats! Lettings, not a good time of year for it. You wouldn’t believe the time we’ve had of it, it has been just one thing after another. Sales is a whole different ball game of course. Well, you’re here now, on time, give or take a day or two. You’re here, you’re ready for action, and everything seems to be in order.’

The soft grey face, creased and misshapen, blinked and nodded while hesitant hands patted change in both pockets of his jacket. ‘Well, well.’ He shuffled across the brown carpet. ‘Well, well, let’s see if we can’t get Mr Dote up and running.’

Toby followed him past the desks along the length of the office. He stood while the old man sacked a bookcase. His jerking hands shunted aside phone directories, spilt magazines to the floor and flailed before a cascade of cream envelopes. He eventually straightened up holding two files. Squinting he examined their spines. ‘Up to a mil above a mil. Chuck?’ This was addressed to the estate agent who, slumped, slack-mouthed over his desk, was snoring in the sullen air.

There was no response.

‘Earth to Chuck.’ Harmsworth-Mallett, birdlike, smiled gently and tapped the side of his head. ‘Our friend is not all there.’

‘Huh?’ Frowning the man raised his fleshy face.

‘Chuck, are these files up to date? Are there any other properties Dote needs to familiarize himself with?’

‘Dote?’ The man frowned and tapped a white card impatiently on his desk. He looked irritably from the old man to Toby.

‘Dote. Sales negotiator, Milson, Range & Rafter, commenced at 9 a.m. on Monday 7 June in the year of our Good Lord 2004.’

‘Huh?’ With some effort the man wheeled back his chair and stood up. He was vast.

‘Dote, this is The Chuckler, our representative from across the pond.’

‘Chuck Lincoln,’ the man held out a meaty hand and regarded Toby steadily. There was a sheen of sweat on his forehead and the hand which engulfed Toby’s was fleshy and wet, but Toby took it with relief. Had this man been Gideon Chancelight, Toby would not have fancied his chances.

The old man chuckled. ‘The competition.’

Chuck frowned and flopped back in his chair and bent once again over his desk.

‘Swings and roundabouts, Chucky, swings and roundabouts.’ He patted the American’s shoulder and laughed softly as he led Toby to the very back of the office and the last desk. It stood poised in darkness at the mouth of a spiral staircase which sank below the road.

‘Your desk, sir.’ He wheeled out the chair with a grand flourish of his free hand, waiter-style, files against his chest. Toby sat and put his briefcase upright on the floor beside his chair.

‘Have a look at what’s cooking,’ Harmsworth-Mallett said as he placed blue folders neatly on the desk, ‘and we’ll get on to more important things, like breakfast.’

Toby opened a file. ‘Milson, Range & Rafter,’ it read. ‘Sales £1,000,000 +.’

‘Some of these are on with other agents. We’ve got agreements with Clark, Kemp… and Sage is it, Chuck? All of them around here except of course John Watford, the King,’ he rolled his eyes, ‘of South Kensington. Well, we’ve all been King at one time or another and isn’t that the truth, Chuck?’

With thick fingers the American massaged the roll of flesh which bulged above his collar. Harmsworth-Mallett straightened the beige telephone on Toby’s desk. Of all the outcomes that Toby had considered, it had never crossed his mind that he might be mistaken for an estate agent and given a job. He cleared his throat. ‘Gideon Chancelight?’ It did not come out as he’d intended.

The girl on the phone at the front of the office stopped talking and turned towards Toby. Harmsworth-Mallett was so close Toby could identify the alcohol on his breath, was it Drambuie?

Chuck turned sideways to offer Toby his profile.

‘Gideon Golden Boy,’ the American muttered after some time, his eye cold and pale-lashed as a pig’s, ‘is on vacation.’ The girl resumed talking and Harmsworth-Mallett exhaled.

‘Skiing is Mr Chancelight, I believe,’ said the old man, patting the back of Toby’s chair. ‘Right, sir, when you’ve had a little look at what’s on where, so to speak, ha ha,’ he tapped the blue folders, ‘we’ll have a recapitulation of what you’ll be requiring. Keys, car – perhaps you have your own? No? No matter, we can offer a lovely little Golf: automatic, air-con, sun roof, etcetera – appointment book, business cards, new shoes…’ he made an exaggerated show of looking under Toby’s desk. ‘And so on and so forth.’ He nodded then straightened. ‘Breakfast,’ he said. ‘There’s nothing like breakfast to set you up for the day.’ Blink, blink. Smile. ‘Cappuccino? Danish?’ The old man held out both hands as though Toby had offered money. ‘It’s on me.’

‘I’m good,’ the American muttered as the old man passed.

‘We know you are, Chuck, we know you are.’ Toby watched him shuffle towards the sunlight and the door. It sounded as though he was wearing slippers.

Gideon Chancelight. Skiing.

It was Monday, it was 9.10 and Imogen, along with her class, should be filing into assembly. Probably he should have visited St Hellier’s first. He should have disobeyed the Code of the Road and ignored the fact that the first visit is to the gentleman. He should have dealt with Imogen before Gideon. But there was something worrying Toby: it fled from him down the passageways of his mind. He pursued it through a spiral of memory away from horror and down train tracks in and out of darkness through high escarpments dizzy with wild flowers to Victoria Station and the vile bulge of Imogen’s red and blue carpet bag packed and ready to go in the hall of the house on Frederick Street. For a moment he had the thing cornered. It shrank black and poisonous against the back wall of his skull. He sprang and for a moment it seemed it was his. Then it swelled and flattened before disintegrating into a bewildering scatter of laughter.

Toby ran a hand across the cool leather top of the desk. He hadn’t had a desk since school and then it had been nothing like this. This was a Chesterfield in miniature. It was something for the smaller headmaster. He opened a drawer. Its varnished front moved independently of its base, scattering the contents – coffee cups, the wrapping from a sandwich, a sachet of tomato ketchup clotting translucent at one corner and a mostly empty can of Coke – on to his knee. The Coke can rolled, releasing liquid on to his trousers and clattered lightly to the floor. It disappeared under the desk. Gideon Chancelight, skiing. Toby felt his next move to be not immediately apparent. In front of him the American’s jacket stretched a yard across his back.

‘Chuck?’ He would have been more comfortable with Charles or even Charlie. There was something grotesque about ‘Chuck’.

The American turned his head ninety degrees; it seemed as much as he could do. In profile the neck bulged over his too-tight collar and his lower lip hung wet and red. He tapped his foot impatiently and waited for Toby to speak.

‘Gideon Chancelight, when is he back?’

The giant’s lips twitched. ‘Tomorrow? End of the week? Armageddon? Who gives a shit?’ The vast head bobbed a few times, thick cropped hair growing straight up at the forehead and trimmed neatly around the ear.

Phones at desks screeched.

‘A-Milson-Range-&-Rafter-good-morning. Who? No, sir. Is there anything I can help you with? Right. Uh-huh. Yuh huh. You got it.’ Replacing the receiver he sighed, raised his head and circled it on his neck. First one direction and then the other. Toby watched the flesh bulge and disappear and then reappear on the other side.

‘Oh brother,’ the American said softly. A bone cracked in his neck. ‘Monday, Monday, Monday.’

Toby turned the title page of the blue folder.

Prince’s Court, Knightsbridge,

it read.

A rare opportunity to purchase this stunning penthouse in the award-winning Prince’s Court. Less than a stone’s throw from the world’s most famous department store, this majestic apartment offers panoramic views across the capital.

He turned the pages. Prince’s Court, Queen’s Gate, Duke Street, Castle Court, Palace Drive. Residences fit for royalty.

Chuck prodded his phone. ‘Hello Mrs York-Jones, Chuck Lincoln, Milson, Range & Rafter – just a quick call re Temple Place as I would reiterate I do not anticipate its being available much longer. Give me a call when you get this and let’s hear your thoughts. 7718 7878. That’s 7718 7878.’ He replaced the receiver and tapped a pencil on his desk top.

It was 9.25 and had Imogen not absconded with an estate agent she would be filing back into her classroom from assembly in time for her first lesson at 9.30. At least that was when Toby presumed lessons started at St Hellier’s. He was ashamed to admit that the timetable he was working from was based on what he remembered of his own school days rather than any knowledge of his girlfriend’s. Alternatively, Imogen was waking in a chalet somewhere mountainous and snowy.

When was the last time Imogen had gone skiing? In the three-and-a-half years they’d been together, including the three they’d lived together at Frederick Street, she’d not once gone skiing, or even suggested it as something she’d like to do. Water-skiing, yes, once. One largely unsuccessful occasion somewhere grey in Suffolk when there had been only one wet suit and he’d gone first and peed in it. Why? He couldn’t remember but smiled anyway at the memory of Imogen getting into it and stretching it up over pale freckled shoulders: ‘Toby, it’s all wet in here.’ No shit, Imogen, that’s why it’s called a wet suit.

The door buzzed. Harmsworth-Mallett, hands full, shouldered the glass. It opened and he ground his cigarette into the pavement behind him, flicking it with an elegant back-kick out into the road. Three polystyrene cups balanced in one hand, the other held a plate of croissants on top of the turret. The girl was still on the phone, the old man stood in front of her desk. She didn’t appear to have seen him and he leant towards her, hesitant and smiling, his forehead wrinkling apologetically.

‘Chloe will you hold on for like one second. Yes?’ She looked up.

‘Skimmed milk latte? Chocolate on top?’ A stage-whisper through a hesitant smile.

She took it and sighed. ‘Sorry Chlo – you there?’

And on he came, smiling and blinking. ‘One cappuccino, one apricot Danish.’ He placed breakfast carefully on Toby’s desk. Chuck held a Post-It up above his head.

‘What have we here?’ With trembling hands Harmsworth-Mallett took it. It stuck to his thumb.

The phones rang. ‘Uh, Milson, Range & Rafter?’

Harmsworth-Mallett winked at Toby. ‘You have to rise early to answer the phones around here. The fastest draw in the West has our Chuck.’ Frowning, he moved the paper towards and then away from his eyes. He shrugged and squinted at the open file on Toby’s desk. ‘Penthouse at Prince’s. A lovely little property and a lovely little deal. One of Mr Chancelight’s, one point two. Wham Bam, thank you very much, very nice too. Ten grand in the bank, should take care of the old overdraft.’ Air whistled through his teeth. ‘Ice to Eskimos. So, rumour has it you come to us from Shayle Nugent… No?’ Harmsworth-Mallett, settling himself on to the corner of Toby’s desk, seemed only mildly surprised. ‘I was sure the boss said Shayles, oh well, where did Mike find you then? McDonald’s?’ Smile smile. Blink blink. ‘What, don’t get it?’ He reached out to touch Toby’s curly hair. ‘Ronald McDonald!’ He bent over to laugh. ‘Well, no matter. Cheap gag. You know how we work here at least.’ He wiped a tear from the corner of one watery eye.

Toby had not been likened to Ronald McDonald since school and he was surprised to find that it caused him to feel something like affection for the old man.

‘Good Lord. They sent us a rookie. Well I never, well I never did. Presumably you are aware of the fact that you will not be receiving a salary? No weekly, monthly, yearly pay cheque. Just commission on each and every sale. You sell, we shell, as it were. Can be very nice… oh yes indeed. Wolves from doors, early retirement, place in Spain, etcetera.’

Toby followed the old man’s gaze beyond the door and across the road to a patch of brightness where the sun glanced off a faded awning.

‘Ah, those were the days.’ He turned back to Toby. ‘And it can be, well, not so nice.’ He indicated the American’s broad back and lowered his voice. ‘Bailiffs, suicide and so on and so forth. Goodbye Jason Townley.’ He tapped Toby’s desk. ‘Goodbye Michelle Lyons. Poor lady didn’t last a week. Hello Mr Dote! Wheat from chaff and all that good stuff. Actually, to tell the truth…’ he lowered his voice still further and nodded, ‘it’s been a bit quiet here for two, three months now. Hence your arrival. Shake things up a little.’

‘And an address,’ Chuck was saying. ‘Very good, sir, I will do my best, traffic-permitting. Ciao.’ He replaced the receiver and with an air of purpose wheeled back his chair and stood up.

‘Chuck?’ Harmsworth-Mallett held out the Post-It still stuck to his thumb.

‘Mr Baker of Fulham Cross said you would know what it’s concerning,’ Chuck secured a pen in his breast pocket.

‘Indeed I do. Our friend Mr Baker,’ Harmsworth-Mallett rolled his eyes, ‘has rats. Rats and more rats. Anywhere nice, Chuck?’

‘Valuation for a Mr Abdul Senior of Flat 7, Albert Mews, a three-bed basement situated on the Albert Hall side.’ The American pushed his chair neatly under his desk and, frowning, straightened it.

‘Take Mr Dote. Permit him to see el maestro in action.’ The old man winked at Toby.

Chuck brushed down each of his shoulders in turn. ‘This party is leaving now,’ he said unwinding the headpiece from his mobile phone and pushing it into his ear as he headed towards the door.

‘Bad news,’ Harmsworth-Mallett said, thoughtful. ‘Mr Abdul Senior sounds like an Indian gentleman which will translate into all manner of horrors. Do not be disheartened, Mr Dote, if you find yourself confronting green carpets, wallpaper and other unmentionables rendering it impossible to shift. Take your breakfast.’ He gestured towards the Danish pastry and the cappuccino.

As Toby stood up an empty sandwich wrapper slid off his knee. The ketchup sachet clung resolutely to his flies. He peeled it off, dropped it under the desk and followed Chuck’s bulk out into sunlight.

‘Skiing apparently,’ Daisy was saying, ‘like Wednesday? Apparently with some new bird. Whatever. Skiing? Nice one Gids, whoever goes skiing in June?’

Whoever goes skiing in June? Whoever indeed. Toby wondered how Imogen might like being ‘some new bird’. Impatient on the pavement, Chuck was squinting in the sunlight and jangling his car keys. The ear-piece of his phone quivered beside his face as he looked Toby up and down, frowning at his boots for a moment before allowing his gaze to return to Toby’s crotch where it remained. Toby looked down: the grey fabric was splashed with something.

‘Car this way,’ said Chuck as he set off down Harrington Gardens, the heels of his shiny shoes moving smartly on the pavement.

As Toby followed he wondered whether perhaps he should have polished his boots and ironed his shirt. He never ironed his shirt. Highwaymen didn’t, archivists didn’t and nor did Toby Doubt. Actually, it was likely that highwaymen did iron their shirts or at least got someone to do it for them. Perhaps if he’d ironed his shirt, he wouldn’t be here now. He’d have finished the book, he’d be a success and the chances were he wouldn’t be facing the fact that his girlfriend had left him for an estate agent. Hal Blake aka the Squire: the tragic tale of history’s least successful highwayman as told by history’s least successful biographer. In fact, that last statement was debatable; in Toby’s view there was another candidate for that position. And that was John Lambert III, author of the entirely impenetrable Friends of Beowolf, published 1975 by Bay Tree Press. On the other hand there was no getting away from the fact that John Lambert III – an American one night stand of his mother’s and also, as it had turned out, Toby’s father – had completed a book and got it published. The thought descended, uninvited, on Toby.

Chuck was bent into an azure Golf to arrange his pinstriped jacket on a coathanger above the back seat. Thick red braces crossed over to frame a sweat-damp blue patch as large as a dinner plate in the centre of his back. Despite this, the straight creases in his sleeves suggested that Chuck was indeed a man who ironed his shirt. He emerged briefly to issue instruction: ‘No food inside’, before pulling his shirt up at the waist and lowering himself heavily into the car.

Toby filled his mouth with sweet pastry and milky coffee before reluctantly discarding his breakfast on a low wall.

Inside the car a sweat patch showed under Chuck’s arm. He rocked in the seat, his hair touching the pale quilted ceiling. Breathing heavily he slotted the key into the ignition and turned it. Toby, lacking air, pushed a button to open the window.

‘AC,’ said Chuck pushing another to close it. Breathing through his nose he adjusted the mirror, pushed the earpiece of his mobile further into his ear and dropped the hand brake. Heavy on the pedals he reversed out of the space.

Toby sat tall in his seat hoping to find more air near the ceiling and wondered when his relationship had gone wrong. To him it seemed that things had not gone wrong. Perhaps that was the trouble: Toby had been content to continue with life as it was for tomorrow, for the next day and for the rest of it. Clearly, Imogen had not.

Three and a half years ago when he spent the night with Imogen for the first time he’d been as sure of her as he was on the Saturday just past, the last time he saw her. Sure as sure is. Sure as sure can be. As sure as when last summer a much-handled, water-damaged scrap of paper dated 1724 had fallen into his hands. It was a warrant for Harold Blake’s death. Hal Blake, aka the Squire, was the most chivalrous, the most romantic and the singularly most dismal highwayman to have ever worked the Great North Road. His failures were legendary until at the age of thirty, betrayed by Jack Scarlett, betrayed by Lady Rose, the Squire was hanged at the Tyburn Gibbet. The scrap of paper was what Toby had been waiting for and he was certain that this was his book to write. Sweating with excitement he’d called Imogen at school. He instructed the secretary to pull her out of class.

‘What’s happened?’ He’d laughed at her voice and told her about the paper. She’d been angry because her mother was ill and she was expecting bad news. This in turn had made Toby angry – that she couldn’t be happy for him – which had resulted in him spending that night downstairs on the sofa.

‘The trouble is,’ his friend Howard had said, offering advice as usual, ‘you’re writing a book about a loser: the world’s worst highwayman. What people want is the best. Why don’t you give the people what they want and write a book about the world’s best highwayman?’

‘So. What brings you to Range Rafter?’ The American pressed his head back against the headrest and watched the mirror.

What indeed? ‘New job,’ said Toby, wondering how that sounded.

‘No shit.’ Chuck flicked his indicator.

‘Money,’ tried Toby.

‘What money?’ Chuck started to pull out. He stopped suddenly. ‘Cheers mate!’ he said in a mock English accent, ‘And fuck you too.’ After another false start he pulled out behind a white van and accelerated to sit on its tail. ‘There ain’t no money to be had round here. Who’s making any? It sure as shit ain’t me.’

‘Gideon?’

‘Not Gideon. He hasn’t sold shit for months. How do you know Gideon?’

‘I don’t. I’ve just heard about him.’

‘I’ve just heard about him,’ he repeated, mimicking Toby. ‘Jesus Christ. Who the fuck is this guy? Superman. Golden Boy Gideon. Gideon this, Gideon that. The guy is a prick.’ Chuck slammed on the brakes. The white van was indicating to turn right and as Chuck swerved to avoid it he turned to look hard at the driver.

‘A word of advice, friend, never let Golden Boy Gideon anywhere near one of your deals.’

Chuck braked sharply at a zebra crossing. A shrivelled woman with a dog so small it looked as though it was on wheels pattered on tiny feet to pass in front of them. ‘Or it ain’t gonna be one of your deals. The guy’s a snake. In your own time, lady…’ The mobile buzzed on the plastic shelf. Chuck snatched it.

‘Chuck Lincoln.’ He held the mouthpiece against his lips. ‘Yeah… seven. I said seven. It will be seven. Yeah… seven.’ He dropped the mouthpiece and wiped his forehead. ‘Seven-o-fuckin’-clock.’ They were running alongside the park’s edge now. Railings flitted across scantily clad people. A red setter trotted waving its tail stupidly, a six-foot branch in its mouth.

‘The wife,’ said Chuck, ‘pregnant.’

‘Oh.’

‘Oh. Yes. Married?’

‘No.’ A man in orange shorts jumped four feet in the air to claim a frisbee from the sky.

‘Hey. Well, that killed that one. “Married?” “No.” Just a little more effort required. “No Chuck, I’m not married. I’m divorced, single, engaged to be married.” Hell, even gay would suffice. “Married?” “No.” Jeeze.’ Chuck’s tongue darted out to moisten his lips. ‘Well I’m married, the wife’s pregnant with our first child. Due August. Boy or girl? No idea. Yes I am excited. Excited as hell. We live in Greenwich. It’s a nice part of London. We’ve lived there for two years next month. We’ve got a nice place. Can see the river from the bathroom window. If you’ve got a two-foot neck. Holy shit. Big fuckin’ deal. I hate this fuckin’ country.’ He swerved to avoid a car which was reversing into a parking space. He turned on the radio and pushed a CD into the machine. It was the Beatles and Chuck turned up the volume. A bead of sweat cut a haphazard path down the flesh of his cheek.