Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: No Exit Press

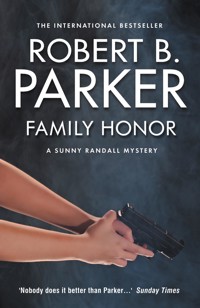

- Kategorie: Krimi

- Serie: A Sunny Randall Mystery

- Sprache: Englisch

Her name is Sunny Randall, a Boston P.I. and former cop, a college graduate, an aspiring painter, a divorcee, and the owner of a miniature bull terrier named Rosie. Hired by a wealthy family to locate their teenage daughter, Sunny is tested by the parents' preconceived notion of what a detective should be. With the help of underworld contacts she tracks down the runaway Millicent, who has turned to prostitution, rescues her from her pimp, and finds herself, at thirty-four, the unlikely custodian of a difficult teenager when the girl refuses to return to her family. But Millicent's problems are rooted in much larger crimes than running away, and Sunny, now playing the role of bodyguard, is caught in a shooting war with some very serious mobsters. She turns for help to her ex-husband, Richie, himself the son of a mob family, and to her dearest friend, Spike, a flamboyant and dangerous gay man. Heading this unlikely alliance, Sunny must solve at least one murder, resolve a criminal conspiracy that reaches to the top of state government, and bring Millicent back into functional young womanhood.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 327

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2014

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

A blazingly original novel from the undisputed dean of American crime fiction, introducing a sassy new female PI.

Her name is Sunny Randall, a Boston PI and former cop, a college graduate, an aspiring painter, a divorcee, and the owner of a miniature bull terrier named Rosie. Hired by a wealthy family to locate their teenage daughter, Sunny is tested by the parents' preconceived notion of what a detective should be. With the help of underworld contacts she tracks down the runaway Millicent, who has turned to prostitution, rescues her from her pimp, and finds herself, at thirty-four, the unlikely custodian of a difficult teenager when the girl refuses to return to her family.

But Millicent's problems are rooted in much larger crimes than running away, and Sunny, now playing the role of bodyguard, is caught in a shooting war with some very serious mobsters. She turns for help to her ex-husband, Richie, himself the son of a mob family, and to her dearest friend, Spike, a flamboyant and dangerous gay man. Heading this unlikely alliance, Sunny must solve at least one murder, resolve a criminal conspiracy that reaches to the top of state government, and bring Millicent back into functional young womanhood.

Robert B. Parker (1932-2010) has long been acknowledged as the dean of American crime fiction. His novels featuring the wise-cracking, street-smart Boston private-eye Spenser earned him a devoted following and reams of critical acclaim, typified by R.W.B. Lewis’ comment, ‘We are witnessing one of the great series in the history of the American detective story’(The New York Times Book Review).

Born and raised in Massachusetts, Parker attended Colby College in Maine, served with the Army in Korea, and then completed a Ph.D. in English at Boston University. He married his wife Joan in 1956; they raised two sons, David and Daniel. Together the Parkers founded Pearl Productions, a Boston-based independent film company named after their short-haired pointer, Pearl, who has also been featured in many of Parker’s novels.

Robert B. Parker died in 2010 at the age of 77.

CRITICAL ACCLAIM FOR ROBERT B. PARKER

‘Parker writes old-time, stripped-to-the-bone, hard-boiled school of Chandler… His novels are funny, smart and highly entertaining… There’s no writer I’d rather take on an aeroplane’

–Sunday Telegraph

‘Parker packs more meaning into a whispered “yeah” than most writers can pack into a page’

–Sunday Times

‘Why Robert Parker’s not better known in Britain is a mystery. His best series featuring Boston-based PI Spenser is a triumph of style and substance’

–Daily Mirror

‘Robert B. Parker is one of the greats of the American hard-boiled genre’

–Guardian

‘Nobody does it better than Parker…’

–Sunday Times

‘Parker’s sentences flow with as much wit, grace and assurance as ever, and Stone is a complex and consistently interesting new protagonist’

–Newsday

‘If Robert B. Parker doesn’t blow it, in the new series he set up in Night Passage and continues with Trouble in Paradise, he could go places and take the kind of risks that wouldn’t be seemly in his popular Spenser stories’

– Marilyn Stasio, New York Times

THE SPENSER NOVELS

The Godwulf Manuscript

Chance

God Save the Child

Small Vices*

Mortal Stakes

Sudden Mischief*

Promised Land

Hush Money*

The Judas Goat

Hugger Mugger*

Looking for Rachel Wallace

Potshot*

Early Autumn

Widow’s Walk*

A Savage Place

Back Story*

Ceremony

Bad Business*

The Widening Gyre

Cold Service*

Valediction

School Days*

A Catskill Eagle

Dream Girl (aka Hundred-Dollar Baby)*

Taming a Sea-Horse

Pale Kings and Princes

Now & Then*

Crimson Joy

Rough Weather

Playmates

The Professional

Stardust

Painted Ladies

Pastime

Sixkill

Double Deuce

Lullaby (by Ace Atkins)

Paper Doll

Wonderland (by Ace Atkins)*

Walking Shadow

Silent Night (by Helen Brann)*

Thin Air

THE JESSE STONE MYSTERIES

Night Passage*

Night and Day

Trouble in Paradise*

Split Image

Death in Paradise*

Fool Me Twice (by Michael Brandman)

Stone Cold*

Killing the Blues (by Michael Brandman)

Sea Change*

High Profile*

Damned If You Do (by Michael Brandman)*

Stranger in Paradise

THE SUNNY RANDALL MYSTERIES

Family Honor*

Melancholy Baby*

Perish Twice*

Blue Screen*

Shrink Rap*

Spare Change*

ALSO BY ROBERT B PARKER

Training with Weights

A Year at the Races (with Joan Parker)

(with John R. Marsh)

All Our Yesterdays

Three Weeks in Spring

Gunman’s Rhapsody

(with Joan Parker)

Double Play*

Wilderness

Appaloosa

Love and Glory

Resolution

Poodle Springs

Brimstone

(and Raymond Chandler)

Blue Eyed Devil

Perchance to Dream

Ironhorse (by Robert Knott)

*Available from No Exit Press

For Joan:

I concentrate on you.

Their last months together had been gothic. Both of them hadavoided being home, and the house in Marblehead with the waterview had stood, more empty than occupied, both emblem and relic oftheir marriage. They had been much younger than their neighborswhen they’d moved in, freshly married, twenty-three years old, thehouse purchased for cash with money from her in-laws. They haddrunk wine in the living room and looked straight out over the Atlanticand held hands and made love in front of the fireplace, andthought about forever. Nine years is a little short of forever, shethought. She had refused alimony. Richie had refused the house.

Now she was carefully bubble-wrapping her paintings and leaningthem carefully against the wall where the movers could pick them upwhen they came. Each painting had a FRAGILE sticker on it. Her paintsand brushes were boxed and taped and stood beside the paintings.The house was silent. The sound of the ocean only made it seemmore silent. The sun was streaming in through the east windows.Tiny dust motes glinted in it. The sun off the water made a kind of backlighting, diffusing the sunlight, and filling in where there would have been shadows. Her dog sat on her tail watching the packing, looking a little nervous. Or was that projection?

When she had married Richie, her mother had said, ‘Marriage is a trap. It stifles the potential of womanhood. You know what they say, a woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.’ Sunny had said, ‘I don’t think they say that too much anymore, Mother.’ But her mother, the queen of doesn’t-get-it, paid no attention. ‘A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle,’ she had said.

When Sunny had announced nine years later that she and Richie were divorcing, her mother had said, ‘I’m very disappointed. Marriage is too hard to be left to men. It is your job to make it work.’ That was her mother. She could disapprove of the marriage and disapprove of the divorce that ended it. Her father had been simpler about both. ‘You should do what you want,’ he had said of her marriage and of her divorce and of everything else in her life. ‘You need help, I’ll help you.’

Her parents were so strangely unsuitable for each other. Her mother was a vocal feminist who had married a policeman at the end of her junior year in college. Her mother had never held a paying job, and had never, as far as her daughter could tell, ever written a check, or changed a tire. Her husband had taken care of her as he had taken care of his two daughters, completely and without comment, which probably gave her the time to be a feminist. He was straight ahead and calm. He said little. What he did say, he meant.

He rarely talked about his job. But he would often come home and eat supper in his shirtsleeves with his gun still on his belt. Her mother would always remind him to take it off. The gun seemed to Sunny the visible symbol of him, of his power, as her therapist had pointed out during her attempt to save the marriage, of his potency. If that were true, Sunny had often wondered what it meant that her mother wouldn’t let him wear it to table. But it was never clear what her mother meant. It was clear what she wanted to mean. Her mother was verbal, combative, theoretical, filled with passion over every new idea, and, Sunny smiled to herself, sad to say, most ideas were pretty new to her mother. Her mother wanted to be a new woman, abreast of every trend, in touch with the range of experience from supermodels to theoretical physics. But she never penetrated any of the ideas she embraced very deeply. Probably, Sunny thought, because she was so desperately shouting, ‘See me, look at me.’ If her father noticed any of his wife’s contradictions, he didn’t comment. He appeared to love her thoroughly. And whether she loved him, or simply needed him completely, Sunny’s mother seemed as committed to him as he was to her. They had been married for thirty-seven years. It was probably what Sunny had had in mind when she and Richie had talked about ‘forever.’

Christ, didn’t we fight over Daddy, Sunny thought, all three of us.

She leaned the last painting against the living room wall. She leaned the folded easel against the wall beside them. The furniture was gone. The rugs were up. The red oak floor gleamed. Without anything in the empty rooms to buffer sound, the dog’s claws rattled loudly as she trotted behind Sunny.

Sunny’s sister was four years older than she was. God, she must have hated me when I was born, Sunny thought. It doubled the competition for Daddy. To win him, they had devised different methods as they had grown up. Her mother, impregnably married to him, persisted serenely in her noisy self-contradictions. Elizabeth, apparently convinced that nothing succeeded like success, tried to be like her. By default Sunny was left to emulate her father. Their mother dressed them both in pinafores and Mary Janes. Their father had built them a large dollhouse, and Elizabeth, with her long curls, had spent hours with it, manipulating her dollies. Sunny had worn her pinafores to the pistol range with Daddy, and while she was too female to be butch, she reveled in the androgyny of her nickname. And she learned to shoot. If one approach worked better than another, it was never evident. Her father persisted in loving his daughters as unyieldingly as he loved their mother. There was something frustrating in it. What you did didn’t matter, he loved you whatever you did.

In the echoing kitchen, there were only the plates and glasses to pack. Sunny took them down, one at a time, and wrapped them in newspaper and put them in the cartons. The movers would have done it, but she wanted to do it herself. Somehow it seemed the right transition from one life to another. She was hungry. In the refrigerator, there was a half-empty jug of white wine, some Syrian bread, and a jar of all-natural peanut butter. She had some bread and peanut butter, and poured herself a glass of jug wine. Beyond the window over the sink she could see the rust-colored rocks stoically accepting the waves that broke in upon them and foamed and slid away. The dog pushed at Sunny’s ankle with her nose. Sunny gave her some bread. Way out along the horizon a fishing boat moved silently. The dog ate her bread and went to her water dish and drank noisily for a long time. Sunny poured another glass of wine.

She had become a cop, the year before her marriage. Two years after her father was promoted to Area D commander. Her mother had asked if she were a lesbian. Sunny had said no. Her mother had seemed both relieved and disappointed. Disappointed, Sunny thought, that shecouldn’t martyr herself to her daughter’s preference for women. Relieved that she didn’t have to. Her mother had said, what about painting? Sunny had said she could do both. What about marriage and children? Sunny wasn’t ready. The clock is ticking. Mother, I’m twenty-two. She remembered wondering if women needed children like fish needed bicycles, but she kept it to herself. The fishing boat had moved maybe an inch across the horizon. She took her wine and went and sat on the floor beside the dog with her knees up and gazed out through the French doors while she drank.

Richie was like her father; she’d known that even before she went to the therapist. He didn’t say much. He was inward and calm and somehow a little frightening. And like her father, he was very much straight ahead, going about his business, doing what he did, without paying much attention to what other people thought or did about it. It was what he did that was one of the issues. He worked in the family business, and the family business was crime. He didn’t do crime. She believed that when he told her. He ran some saloons that the family owned. But… she poured some more wine from the jug into her glass. There was a sort of ravine behind the house that ran down to the ocean, and the waves as they rolled into it sent up a harsh spray. Sitting on the floor she could see only the spray, disembodied from the ocean, appearing rhythmically above the slipping lawn… It wasn’t really that he was from a crime family any more than it was that she was from a cop family. It had to do with much tougher stuff than that and she’d learned early in their separation not to pretend that it was just cops versus robbers. A gull with a white chest and gray wings settled down past her line of vision and disappeared into the ravine and came back up with something in its mouth and flew away. Richie loved her, she knew he did. The factthat her father had spent a lifetime trying to jail his father didn’t help, but that wasn’t what felt so sharp and sore in her soul. Richie was so closed, so interior, so certain of how things were supposed to go, so too much like her father that she felt as if she was dwindling every year they were together, smaller and smaller.

‘Dwindle,’ she said aloud.

The dog turned her head and cocked it slightly and pricked her big ears a little forward. Sunny drank some wine.

‘Dwindle, dwindle, dwindle.’

Her friend Julie had said once to her that she was too stubborn to dwindle. That her self was so unquenchable, her autonomy needs so sharp, that no one could finally break her to a marriage. Julie was a therapist herself, though not by any means Sunny’s, and maybe she knew something. Whatever had happened they had been forced to admit it didn’t work, after a nine-year struggle. Sitting across from one another in the restaurant of a suburban hotel, they had begun the dissolution.

‘What do you want?’ Richie had said.

‘Nothing.’

Richie had smiled a little bit.

‘Hell,’ he’d said. ‘I’ll give you twice that.’

She had smiled an even smaller smile than Richie’s.

‘I can’t strike out on my own at your expense,’ she had said.

‘What about the dog?’

She had been silent, trying to assess what she could stand.

‘I want the dog,’ she had said. ‘You can visit.’

He had smiled the small smile again.

‘Okay,’ he had said. ‘but she’s not used to squalor. You keep the house.’

‘I can’t live in the house.’

‘Sell it. Buy one you can live in.’

Sunny had been quiet for a long time, she remembered, wanting to put out her hand to Richie, wanting to say, ‘I don’t mean it, let’s go home’. Knowing she could not.

‘This is awful,’ she said finally.

‘Yes.’

And it was done.

Out through the French doors the fishing boat had finally inched out of sight and the horizon was empty. Sunny pulled the dog onto her lap. And sang to her.

‘Two drifters, off to see the world/There’s such a lot of world to see.’

She couldn’t remember the words right. Maybe it was two dreamers. Too much wine. The dog lapped the back of Sunny’s hand industriously, her tail thumping. Sunny sipped a little more of her wine. Got to go slow here. She sang again to the dog.

She wanted to be alone, now she was alone. And she didn’t want to be alone. Of course, she wasn’t really alone exactly. She had a husband – ex-husband – she could call on. She had friends. She had parents, even her revolting sister. But whatever this thing was, this as yet unarticulated need that clenched her soul like some sort of psychic cramp, required her to put aside the people who would compromise her aloneness. You lose, you lose; you win, you lose.

‘You and me,’ she said to the dog. ‘You and me against the world.’

She hugged the dog against her chest, the dog wriggling to lap at her ear. Sunny’s eyes blurred a little with tears. She rocked the dog gently, sitting on the floor with the jug of wine beside her and her feet outstretched.

‘Probably enough wine,’ she said out loud, and continued to rock.

1

One of the good things about being a woman in my profession is that there’s not many of us, so there’s a lot of work available. One of the bad things is figuring out where to carry the gun. When I started as a cop I simply carried the department-issue 9-mm on my gun belt like everyone else. But when I was promoted to detective second grade and was working plainclothes, my problems began. The guys wore their guns on their belts under a jacket, or they hung their shirt out over it. I didn’t own a belt that would support the weight of a handgun. Some of them wore a small piece in an ankle holster. But I am 5´6˝ and 115 pounds, and wearing anything bigger than an ankle bracelet makes me walk as though I were injured. I also like to wear skirts sometimes and skirt-with-ankle-holster is just not a good look, however carefully coordinated. A shoulder holster is uncomfortable, and looks terrible under clothes. Carrying the thing in my purse meant that it would take me fifteen minutes to find it, and unless I was facing a really slow assailant, I would need to get it out quicker than that. My sister Elizabeth suggested that I had plenty of room to carry the gun in my bra. I have never much liked Elizabeth.

At the gun store, the clerk wanted to show me a LadySmith. I declined on principle, and bought a Smith & Wesson .38 Special with a two-inch barrel. With a barrel that short you could probably miss a hippopotamus at thirty feet. But any serious shooting I knew anything about took place at a range of about three feet, and at that range the two-inch barrel was fine. I wore my .38 Special on a wider-than-usual leather belt in a speed holster at the small of my back under a jacket.

Which is the way I was wearing it on an early morning at the beginning of September as I drove through a light rain up a winding half-mile driveway in South Natick, dressed to the teeth in a blue pant suit, a white silk tee shirt, a simple gold chain, and a fabulous pair of matching heels. I was calling on a lot of money. The driveway seemed to be made of crushed seashells. There were bright green trees along each side, made even greener by the rain. Flowering shrubs bloomed in serendipitous places among the trees. The whole landscape, refracted slightly by the rain, made me think of Monet. At the last curve in the driveway the trees gave onto a rolling sweep of green lawn, upon which a white house sat like a great gem on a jeweler’s pad. The vast front was columned, and the Palladian windows seemed two stories high. The drive widened into a circle in front of the house, and then continued around back where, no doubt, unsightly necessities like the garage were hidden.

As soon as I parked the car a black man wearing a white coat came out of the house and opened the door for me. I handed him one of my business cards.

‘Ms. Randall,’ I said. ‘For Mr Patton.’

‘Yes, ma’am,’ the black man said. ‘Mr Patton is expecting you.’

He preceded me to the door and opened it for me. A good-looking black woman in a little French maid’s outfit waited in the absolutely massive front hallway.

‘Ms. Randall,’ the man said and handed the maid my card.

She took it without looking at it and said, ‘This way, please, Ms. Randall.’

The foyer was very air-conditioned, even though the rainy September day was not very hot. The maid walked briskly ahead of me, her heels ringing on the stone floor. If her shoes were as uncomfortable as mine, she was as stoic about it as I was. My heels rang on the stone floor, too. The foyer was decorated with some expensively framed landscape paintings, which were hideous, but probably made up for it by costing a lot. Through the French doors at the far end of the foyer I could see a croquet lawn and, beyond that, a more conventional lawn that sloped down to the river at the far bottom.

The maid opened a door near the end of the foyer and stood aside. I stepped in. The air-conditioning was even more forceful than it had been in the foyer. The room was a man’s study, and it absolutely howled of decorator. Bookshelves were filled with leather-bound books artfully arranged. The walls were done in a dark burgundy. The drapes matched the walls but with a golden triangular pattern in them. There was a fireplace that I could have stood upright in on the wall opposite. There was a fire in it. The ceiling was far above my head. There was a massive reddish wooden desk along the left wall of the room with Palladian windows opening behind it. The deep colorful rugs had been woven somewhere in the far east. A huge globe of the world was on its own dark wooden stand near the fireplace. It was lit from within. Above the fireplace was a formal portrait of a good-looking woman with smooth blond hair and the contemptuous smile of a well-fed house cat.

The maid marched across the rug and put my card on the desk and announced, ‘Ms. Randall.’

The man behind the desk said, ‘Thank you, Billie,’ and the maid turned and marched out past me and closed the door. The man looked at my card for a little while without picking it up, and then he looked up at me and smiled. It was an effective smile and I could tell that he knew it. The little crinkles at his eyes made him look kind though wise, and the parentheses around his mouth gave him a look of firm resolve.

‘Sunny Randall,’ he said, almost as if he were speaking to himself. Then he rose and came around the desk. He was athletic-looking, taller than my ex-husband, with blue eyes and a healthy outdoor look about him. He put his hand out as he walked across the carpet.

‘Brock Patton,’ he said.

‘How very nice to meet you,’ I said.

He stood quite close to me as we shook hands, which allowed him to tower over me. I didn’t step back.

‘Where did you get a name like Sunny Randall?’ he said.

‘From my father,’ I said. ‘He was a great football fan and I guess there was some football person with that name.’

‘You guess? You don’t know?’

‘I hate football.’

He laughed as if I had said something precocious for a little girl. ‘Well, by God, Sunny Randall, you may just do.’

‘That’s often the case, Mr Patton.’

‘I’ll bet it is.’

Patton went around his desk and sat. I took a seat in front of the desk and crossed my legs and admired my shoes for a moment. Of course they were uncomfortable; they looked great. Patton appeared to admire them, too.

‘Well,’ he said after a time.

I smiled.

‘Well,’ he said again. ‘I guess there’s nothing to do but plunge right in.’

I nodded.

‘My daughter has run off,’ he said.

I nodded again.

‘She’s fifteen,’ he said.

Nod.

‘My wife and I thought somehow a woman might be the best choice to look for her.’

‘You’re sure she’s run away?’ I said.

‘Yes.’

‘She ever do this before?’

‘Yes.’

‘Where did she run to before?’

‘She didn’t get far. Police picked her up hitchhiking with three other kids… boys. We were able to keep it out of the papers.’

‘Why does she run away?’ I said.

Patton shook his head slowly, and bit his lower lip for a moment. Both movements seemed practiced.

‘Teenaged girls,’ he said.

‘I was a teenaged girl,’ I said.

‘And I’ll bet a cute one, Sunny.’

‘Indescribably,’ I said, ‘but I didn’t run away.’

‘Well, of course, not all teenagers…’

‘Things all right here?’ I said.

‘Here?’

‘Yes. This is what she ran away from.’

‘Oh, well, I suppose… everything is fine here.’

I nodded. To my right the fireplace crackled and danced. No heat radiated from it. The air-conditioned room remained cold. The windows fogged with condensation in which the rain streaked little patterns.

‘So why did she run away?’

‘Really, Sunny,’ Patton said. ‘I am trying to decide whether to hire you to find her.’

‘And I’m trying to decide, Brock, if you do offer me the job, whether I wish to take it.’

‘Awfully feisty,’ Patton said, ‘for someone so attractive.’

I decided not to blush prettily. He stood suddenly.

‘Do you have a gun, Sunny?’

‘Yes.’

‘With you?’

‘Yes.’

‘Can you shoot it?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’m something of a shooter myself,’ Patton said. ‘I’d like to see you shoot. Do you mind walking outside in the rain with me?’

Other than the fact that my hair would get wet and turn into limp corn silk? But there was something interesting happening here. I wasn’t sure what it was, but I didn’t want to miss it.

‘I don’t mind,’ I said.

He took an umbrella from a stand beside the French doors behind his desk. He opened the doors and we went out into the rain. He held the umbrella so that I had to put my arm through his to stay under cover. We walked across the soft wet grass, my heels sinking in uncomfortably. Maybe there should be a new rule about wearing heels when I was working. Maybe the new rule would be, never. On the far side of the croquet lawn, and shielded from it by a grove of trees, was an open shed with a sort of counter across one side and a wood-shingled roof. We went to the shed and under the roof. Patton closed the umbrella. He took a key from his pocket and opened a cabinet under the counter and took out something that looked like a small clay frisbee.

‘What have you for a weapon?’ Patton said.

I took out my .38 Special.

‘Well, very quick,’ he said. ‘Think you could hit anything with that?’

There was a test going on, and I didn’t know quite what was being tested.

‘Probably,’ I said.

He smiled down at me.

‘I doubt that you can hit much with that thing,’ he said.

‘What is your plan?’ I said.

‘I’ll toss this in the air, and you put a bullet through it.’

If I did that using a handgun with a two-inch barrel it would be by accident. He knew it.

‘I’ll toss it up here,’ he said, ‘it’s safe to fire toward the river.’

He looked at me and raised his eyebrows. I nodded. He smiled as if to himself and stepped out of the shed and tossed the disk maybe thirty feet straight up into the air. I didn’t move. The disk hit its zenith and came down and landed softly on the wet grass about eight feet beyond the shed. And lay on its side. I walked out of the shed, and over to the disk, and standing directly above it, I put a bullet through the middle of it from a distance of about eighteen inches. The disk shattered. Patton stared at me.

‘I don’t need to be able to shoot something falling through the air thirty feet away,’ I said. ‘This gun is quite effective at this range, Brock, which is about the only range I’ll ever need it for.’

I put the gun away. Patton nodded and stared at the disk fragments for a moment or two; then he picked up the umbrella and opened it and handed it to me.

‘Come back in,’ he said. ‘I’d like you to meet my wife.’

Then he walked away bareheaded in the nice rain. I followed him, alone under the umbrella.

2

Betty Patton was far too perfect. She annoyed me on sight in the same way Martha Stewart does. Her hair was too smooth. Her makeup was too subtle. Her legs were too shapely. Her pale yellow linen dress fit her much too well. She sat with one perfect leg crossed over the other in a low armchair in the study sipping coffee. The cup and saucer were bone-colored. There was a slim gold band around the rim of the cup. When Brock introduced us, she smiled without rising and offered her hand gracefully. Her handshake was firm but feminine. She said she was pleased to meet me. She called me Ms. Randall. I don’t know how she did it, but any neutral observer would have known at once that Betty was the employer, and I was the employee.

‘You’ve been shooting,’ Betty said.

‘Yes.’

‘Can she shoot, Brock?’

‘Well, sort of,’ Brock said.

‘Did you ask Brock to shoot, Ms. Randall?’

‘No,’ I said. ‘I didn’t.’

‘Oh, well, you’ve disappointed him badly then. That was the real point of the exercise.’

I had nothing to say about that, and I said it. The decorative fire was still burning vigorously. A servant must have fed it while we were out. The air-conditioning was still fogging the glass in the French doors.

‘I think Ms. Randall is who we need,’ Brock said.

Betty smiled and sipped her coffee. She didn’t spill a drop on her dress. She wouldn’t.

‘I rather expected you to think so,’ Betty said when the elegant cup was perfectly centered back in the elegant saucer. ‘She’s quite pretty.’

‘She has a good background,’ Brock said. ‘She is straightforward. And I have the sense that she is discreet.’

Discreet about what?

‘Do you think you can find our Millicent?’ Betty said, leaning forward slightly as if to make her question more compelling. Like her husband, she seemed incapable of an unrehearsed gesture.

‘Probably,’ I said.

‘Because?’

‘Because I’m really quite good at this.’

Betty smiled interiorly.

‘Odd profession for a woman,’ she said.

‘Everyone says that.’

‘Really?’

I knew it would annoy her to be clumped in with everyone.

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘Usually they say it just as you did.’

‘Are you married?’

‘No, I’m not.’

‘Ever been married?’

‘Yes.’

‘So you’re not a lesbian.’

‘Having been married doesn’t prove it.’

‘Well, are you?’

‘I guess that’s not germane.’

Betty stared at me for a moment. A perfect little frown line appeared between her flawless eyebrows.

‘That’s rather uppity, Miss Randall,’ she said.

‘Oh, I can be much more uppity than this, Mrs Patton.’

She was motionless for a moment and then turned to her husband.

‘I’m afraid she won’t do, Brock.’

‘Oh for God’s sake, Betty. Maybe you could stop being a bitch for a minute.’

Again Betty was motionless. Then she put her cup and saucer on the coffee table, and rose effortlessly, the way a dancer might, and walked from the room without another word. I watched her husband watch her go. There was nothing in his look that told me what he felt about her. Maybe that was what he felt about her.

‘Don’t mind Betty,’ he said finally. ‘She can be difficult.’

‘I would imagine,’ I said.

He smiled. ‘She’d have preferred someone less attractive.’

‘I’m trying,’ I said.

He smiled widely. ‘And failing, may I say?’

I nodded. ‘Your daughter’s name is Millicent?’

‘Yes – Millie.’

‘When did she disappear?’

‘She hasn’t disappeared,’ Patton said. ‘She’s run off.’

‘When did she run off?’

‘Ah, today is Wednesday,’ he leaned forward and looked at the calendar on his desk. ‘She went not this past Monday, but, ah, a week ago Monday.’

‘Ten days?’ I said.

‘Yes. I know it seems long, but, well, we weren’t too worried at first.’

‘She’s done this before?’ I said.

‘Well, in a sense, that is, she’s gone off to stay with a friend for a couple of days.’

‘Without telling you?’

‘You know how rebellious teenagers are,’ he said.

‘I’m not judging your daughter or you, Mr Patton. I’m trying to find a place to start.’

‘I have a picture,’ he said.

He took a manila envelope out of his desk drawer, and handed it across to me. I took the picture out and looked at it. It was a good picture, not one of those bright-colored school photos in the cardboard folders that I used to bring home every year. It showed a pretty girl, perhaps fifteen, with straight blond hair and her mother’s even features. There was no sign of life in the picture. Her eyes were blank. She seemed to be wearing her face like a mask.

‘Pretty, isn’t she?’ he said.

‘Yes. This a good likeness?’

‘Of course, why do you ask?’

‘Well, just that sometimes people look a little more, ah, relaxed in real life, than they do in studio photographs.’

‘That’s a good likeness of Millie,’ he said.

‘May I keep this?’

‘Of course.’

‘You know what she was wearing when she left?’

‘No, I’m sorry, she had so many clothes.’

‘Take anything with her?’

He shook his head, with that false helplessness men like to adopt when talking about women.

‘And have you any suggestion where I should start?’

‘You might ask at the school?’

‘Which is?’

‘Pinkett School,’ he said. ‘In Belmont. The headmistress is Pauline Plum.’

Pauline Plum. From Pinkett. How darling.

3

‘What was he like?’ Julie said.

Behind Julie, the light was slanting into my loft from the South Boston waterfront. It came in through the big window at the east end, and splashed over my easel, making an elongated Ichabod Crane shadow on the floor. Just out of the shadow, in the warmest part of the sunlight, my bull terrier, Rosie, was lying on her back with her feet in the air and her head lolled over so she could keep an almond-shaped eye on our breakfast.

‘Tall, cute little crow’s-feet around the eyes,’ I said. ‘Great hair.’

‘Nice?’

‘A little impressed with himself.’

‘But you liked him?’

‘Not much,’ I said.

Julie took a bite of her sesame seed bagel and a sip of her coffee.

‘Money?’

‘It would seem so. Huge house, servants, a croquet lawn, trap shooting, river view.’

‘In South Natick?’

‘There’s still land left there,’ I said. ‘This is a very big property.’

Rosie got up and came over and sat the way bull terriers do, with her tail balancing the back of her and her butt several inches from the ground. She looked steadily at me now, her narrow black eyes implacable in their desire for a bite. I broke off a piece of bagel and handed it to her.

‘How about the wife?’

I had a mouthful of coffee and couldn’t answer so I just shook my head.

‘We don’t like the wife,’ Julie said.

I swallowed the coffee.

‘No, we don’t,’ I said. ‘Arrogant, impeccable, condescending.’

‘God, I hate impeccable,’ Julie said. ‘They get along?’

‘Maybe not. I almost had the sense she was jealous of me.’

‘Oh ho,’ Julie said. ‘He seem interested in you?’

‘He might have been.’

‘Well, that’s not so bad. Tall, crinkly, rich, and interested.’

‘And married.’

‘That doesn’t have to be an obstacle,’ Julie said.

‘It is to you.’

‘Well yes, but Michael and I get along,’ Julie said. ‘And even if I wanted to cheat I’d have to get a baby-sitter.’

Julie was always eager for me to have an affair, I think, so she could hear about it afterward.

‘How is life among the rug rats?’ I said.

‘Mikey has discovered that if he doesn’t eat I go crazy.’

‘It’s good to have a resourceful kid.’

‘The little bastard won’t eat anything but macaroni with butter on it.’

‘So?’

‘So it’s not balanced.’

‘Oh hell,’ I said. ‘People live quite well on a lot worse.’

‘He needs protein and vegetables.’

‘Maybe he sneaks some when you’re not looking. You’re the psychiatric social worker,’ I said. ‘What would you say to someone about that?’

‘That it’s one of the few areas where he can exercise control,’ Julie said. ‘I can’t force him to eat.’

I nodded encouragingly.

‘Like toilet training,’ Julie said.

‘Didn’t you have trouble toilet-training him?’ I said.

‘So what do I tell the pediatrician when she tells me he’s malnourished?’

‘Tell her he’ll get over it,’ I said.

‘Oh sure. It’s easy… you haven’t got any children.’

‘All I did was ask a couple of questions. Besides, I have Rosie.’

‘Whom you spoil horrendously.’

‘So?’ I said. ‘Your point?’

Julie finished her sandwich. ‘I can’t wait,’ she started.

And I finished for her, ‘Until you have kids!’

We both laughed.

‘The mother’s curse,’ Julie said. ‘How old is this girl you’re looking for?’

‘Fifteen,’ I said.

We were through breakfast and putting the dishes into the dishwasher.

‘Pretty?’

‘Come on down to the office,’ I said, ‘I’ll show you her picture.’

The kitchen was in the middle of the loft. Behind it was my bedroom. The east end was where I painted. The west end was my office. Julie and I stood near my desk looking down at the picture of Millicent Patton. Rosie followed us and flopped down behind me. I knew she was annoyed. She never understood why I couldn’t just stay still near where she was sleeping.

‘Well, at least she doesn’t have purple hair and a ring in her nose,’ Julie said.

‘At least not in the picture,’ I said.

‘If things are good at home,’ Julie said, ‘kids don’t run away.’

‘True,’ I said. ‘But what defines bad at home will vary a lot from kid to kid.’

‘So where will you start looking for this little girl?’ Julie said.

‘Do the easy things first,’ I said. ‘Call the local police to see if they’ve picked up a juvenile that might be Millicent or found any unidentified bodies that might be Millicent.’

Julie shook her head as if to make the thought go away.

‘Have you done that?’

‘Yes. No one fits.’

‘Good. Now what?’