Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Renard Press

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

Fantomina, or, Love in a Maze is a novella by Eliza Haywood which charts an unnamed female protagonist's pursuit of the charming, shallow Beauplaisir. Dealing with major themes such as identity, class and sexual desire, and first published in 1725, 'Fantomina' subverts the popular 'persecuted maiden' narrative, and reaches a climax which would have shocked its contemporary readership. Moving to London, a young woman – let's call her Fantomina – meets a dashing man at the theatre. After a short, but intense, fling, Beauplaisir grows bored of Fantomina, and leaves her. Outraged that she should be so treated, Fantomina discards her disguise in favour of another, and sets off in hot pursuit of her victim, and a game of cat and mouse begins. This edition features an introduction by Dr Sarah R. Creel, Bethany E. Qualls and Dr Anna K. Sagal of the International Eliza Haywood Society.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 76

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2021

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Ähnliche

Fantomina or, Love in a Maze

eliza haywood

with an introduction by

Sarah R. Creel, Bethany E. Qualls and Anna K. Sagal

renard press

Renard Press Ltd

124 City Road

London EC1V 2NX

United Kingdom

020 8050 2928

www.renardpress.com

Fantomina, or, Love in a Maze first published in 1725

This edition first published by Renard Press Ltd in 2021

Edited text © Renard Press Ltd, 2021

Introduction © Sarah R. Creel, Bethany E. Qualls and Anna K. Sagal, 2021

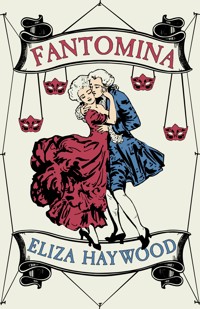

Cover design by Will Dady

Renard Press is proud to be a climate positive publisher, removing more carbon from the air than we emit and planting a small forest. For more information see renardpress.com/eco.

All rights reserved. This publication may not be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means – electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise – without the prior permission of the publisher.

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe

Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia

contents

Introduction

Fantomina

Notes

introduction

by Sarah R. Creel, Bethany E. Qualls and Anna K. Sagal

There is more to say about Eliza Haywood (née Fowler) than could possibly fit into an introduction, but suffice it to say that she is an eighteenth-century author whose body of work is incredibly expansive, yet only recently has scholarly attention been turned her way. In fact, Eliza Haywood is having a bit of a moment. Fantomina, in particular, has become a familiar text within the university classroom for its enduring tropes and fascinating titular character. This edition aims Fantomina (first published in 1725) at an even broader audience – bringing Haywood’s imaginative and complex story squarely into the twenty-first century at a moment when she’s sorely needed, both for her witty narrative capacity and for her shrewd exposé of women’s lives and how they struggle(d) against a patriarchal system that held few, if any, opportunities for them.

So who was this woman whose oeuvre so delights and fascinates us today, but who only recently became part of a wider literary conversation? It is largely assumed that Eliza Haywood was born around 1693, but we do not know for certain. We do know that she died on the 25th of February 1756, aged somewhere around 60–63. She was buried in St Margaret’s churchyard, Westminster, with no known grave marker, while many of her male predecessors, contemporaries and successors are enshrined in the illustrious Poet’s Corner inWestminster Abbey.

Of unknown parentage, Haywood entered the historical record in 1714 in the cast lists of Smock Alley Theatre in Dublin. At this point, she was using the surname ‘Haywood’, but a husband of the same name has not been found in any historical register. Two letters from the late 1720s indicate that she had two children, but about as much is known of them as Mr Haywood. As this brief biography suggests, details about Haywood’s personal life are frustratingly scant, and literary scholars and historians alike have combed the inner recesses of libraries and private collections, trying to find out more about her – anything to help us better understand one of the most prolific writers of the eighteenth century. But Haywood herself requested that her letters be destroyed at the end of her life – a move that makes it difficult to discover more personal facts about her.

While we may not be able to piece together many details of Haywood’s life, her body of work speaks for itself. Shortly after her time in Dublin as an actress, Haywood began writing works of fiction in an ‘amatory’ style (described in more detail below), as was popular at the time. Writing for money, however, was not a respectable career for a woman in the eighteenth century, and, well, one might see how writing tales of seduction would not necessarily add credence to her reputation. But Eliza Haywood shirked the typical her entire life. She tended to follow trends rather than bow to societal pressure, a characteristic that scholars and fans of her work find both charming and frustrating, as later in her life she switched to writing in a more religious ‘conduct book’ style, often correcting and admonishing her earlier amatory characters in her later work.

Not much about Eliza Haywood’s life, or even her work, is easy to understand. Yet her work challenges, captivates and shows us that she was an author who expanded herself alongside the literary marketplace, leaving us with works like Fantomina that continue to delight and mystify.

While Fantomina is unarguably a compelling text for modern readers, some contextualisation of significant socio-cultural differences between the twenty-first and eighteenth centuries are useful for a contemporary audience.

The novella’s depiction of human sexuality – male and female – draws upon several widely circulating stereotypes of masculinity and femininity. We begin by meeting the unnamed narrator, a wealthy ingénue who has been raised in the country but is now spending her time mostly unsupervised in London. For eighteenth-century readers, this would have immediately raised some red flags. She is understandably intrigued by the sophisticated, fashionable world of London, but as ‘a Stranger to the World’, she is unable to appropriately respond to the social dynamics of the theatre crowd and its sexual undercurrents. Deciding to dress ‘in the Fashion of those Women who make sale of their Favours’ (i.e. prostitutes) is framed as ‘the Gratification of an Innocent Curiosity’. However, as any regular reader of fiction in the period would have known, this small misstep will inevitably lead to greater sins. Haywood differs from many of her fellow authors by assigning blame for this error in judgement not only to the pseudonymous female protagonist, but also to her conveniently absent London aunt, who is supposed to chaperone the young country lady, and to her recurrent seducer Beauplaisir.

Beauplaisir represents a popular model of risqué masculinity in eighteenth-century literature: the rake. The figure of the rake or libertine evoked for readers a charming, sexually assertive man whose desires were not shaped by marriage, respect for women or social propriety. Beauplaisir (whose Francophone name signals ‘good pleasure’ – a helpful clue that his most meaningful character trait is his interest in amorous affairs) isn’t among the worst of the eighteenth-century libertines in fiction, but he does pursue multiple sexual relationships with the protagonist, believing her to embody various sexual archetypes: the courtesan, the housemaid, the widow and a glamorously elusive wealthy woman. The pursuit of extramarital or recreational sex does not automatically confer the status of libertine on a man; in fact, male infidelity in aristocratic marriages was not uncommon, and, unlike their wives, husbands had relative legal and social laxity when it came to extracurricular activities. Where Beauplaisir is most at fault, according to Fantomina and to Haywood, is in the ease with which he discards sexual partners in favour of someone new and more sexually exciting (the irony being that none of these ‘new’ sexual partners actually is).

In adopting each of these characters to sexually attract Beauplaisir, Fantomina demonstrates a greater awareness of sexual modes of performance than her initial inability to recognise the women in the theatre box as prostitutes would suggest. Haywood, at least, knows that her readers would be able to interpret the character’srotating disguises as a series of recognisable models of appealing femininity. While prevailing social codes regarding female sexuality and feminine expression of desire absolutely condemned Fantomina’s pursuit of physical pleasure, there is also a clear indication that Haywood wants us to admire Fantomina’s cleverness and to recognise the very real frustration she feels as a (repeatedly) betrayed woman.

In fact, one of Haywood’s recurring concerns in fiction is the vulnerable social position of women in eighteenth-century society and the dangers of their precarious economic and legal status. Many of her novels recount stories of female characters abused, betrayed, abandoned and victimised by a variety of horrible men. Unfortunately, there were very few legitimate ways for women to respond to male betrayal. A few, like the Baroness de Tortillée in The Injur’d Husband (1722), take vengeance into their own hands, but in doing so become infamous villains. Simultaneously, however, Haywood was aware of the role that women could play in their own safety; it is no coincidence that many of her less fortunate female characters who meet bad ends are occasionally complicit in their own demise. More broadly, Haywood’s other writing, like Epistles for the Ladies (1749) and The Female Spectator (1744–46), use a shorter essay form to address various social, political and sexual politics, emphasising the importance of women looking after other women – ultimately, men cannot be trusted to do so.