Erhalten Sie Zugang zu diesem und mehr als 300000 Büchern ab EUR 5,99 monatlich.

- Herausgeber: Inkspot Publishing

- Kategorie: Gesellschafts- und Liebesromane

- Sprache: Englisch

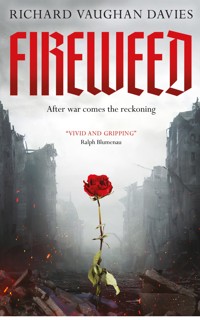

Hamburg, 1947. Adam is a young British lawyer is posted to the destroyed city to assist in the prosecution of Nazi war criminals, an exhausting, soul-destroying and demoralising task. He falls in love with a German prostitute during a time of strict anti-fraternisation rules. Rose is beautiful, educated, clever, witty … and Adam becomes increasingly obsessed with her. Then a Nazi prisoner, responsible for the cold-blooded killing of hundreds of innocents, escapes while in Adam's custody. There is only one place for the desperate man to hide: in Hamburg's forbidden Dead Zone. And Adam is even more desperate to find him, no matter what the cost. At once an adventure, an unconventional love story and an examination of individual culpability in the face of historical horrors. The novel poses uncomfortable questions about ordinary Germans and their possible collusion in the atrocities committed in the name of the Fatherland, and whether people from other nations, in the same circumstances, would have behaved differently. Those of us who look back in time can only hope we will never be similarly tested.

Sie lesen das E-Book in den Legimi-Apps auf:

Seitenzahl: 415

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2023

Das E-Book (TTS) können Sie hören im Abo „Legimi Premium” in Legimi-Apps auf:

Sammlungen

Ähnliche

Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Epigraph

Chipping-on-the-Fosse

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chipping-on-the-Fosse

Acknowledgements

First edition published in 2018 by Mitford Oak Press. Second edition published in 2023 by Inkspot Publishing

www.inkspotpublishing.com

All rights reserved

© Richard Vaughan Davies, 2023

The right of Richard Vaughan Davies to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. No part of this publication may be copied, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior permission of the author, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

ISBN (eBook): 978-1-7396305-6-0

ISBN (Paperback): 978-1-7396305-4-6

Cover Design: Mark Ecob

All the world’s a stage,

And all the men and women merely Players;

They have their exits and their entrances,

And one man in his time plays many parts,

His Acts being seven ages. At first, the infant,

Mewling and puking in the nurse’s arms.

Then the whining schoolboy, with his satchel

And shining morning face, creeping like snail

Unwillingly to school. And then the lover,

Sighing like furnace, with a woeful ballad

Made to his mistress’ eyebrow. Then a soldier,

Full of strange oaths and bearded like the pard,

Jealous in honour, sudden and quick in quarrel,

Seeking the bubble reputation

Even in the cannon’s mouth. And then the justice,

In fair round belly with good capon lined,

With eyes severe and beard of formal cut,

Full of wise saws and modern instances;

And so he plays his part. The sixth age shifts

Into the lean and slippered pantaloon,

With spectacles on nose and pouch on side;

His youthful hose, well saved, a world too wide

For his shrunk shank, and his big manly voice,

Turning again toward childish treble, pipes

And whistles in his sound. Last scene of all,

That ends this strange eventful history,

Is second childishness and mere oblivion,

Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.

William Shakespeare

Chipping-on-the-Fosse

The sun had already started to warm the flagged patio and the worn steps, burnishing the ancient Cotswold stone to an even deeper gold. The nearby picture postcard villages like Bourton-on-the-Water and Chipping Campden would be full of tourists by now, all glued to their mobile phones.

Apparently startled by the sight of a large jet airliner high above it, a tiny lizard disappeared into a crack in the stones in a flicker of green lightning. The plane left a long contrail behind it, like a child’s scrawl on a drawing pad. Two Red Admirals fluttered around the lavender, and the big white buddleia buzzed with flies and hornets. Pigeons cooed their little song to each other, and rooks were wheeling in the tall trees beyond the end of the garden, engaged in their endless quarrel. A perfect day in rural England.

Adam groaned. A summer morning and a cloudless blue sky gave him no pleasure.

A large bumblebee scrabbled angrily at one of the lead-lined window panes. The creature was maddened, trapped indoors by an invisible barrier. How could that round substantial body, so handsome in its black and gold livery, lift itself up with just the use of those fragile wings? It simply couldn’t be done, had been proven to be aerodynamically impossible, yet the bee was doing it.

Adam strained to turn the window latch to allow the bee its freedom, but his arthritic hand hadn’t the strength for the job. Like his legs. His right one was now completely useless. Several knee operations had made it progressively worse. It was a corpse of a leg, and he had to drag it everywhere, like a superfluous item of bony luggage.

In his late eighties, Adam was at a permanent ninety-degree angle to the floor, the original L-shaped man. The advance of his disease steadily forced his head ever further down, so that he now viewed everything from a new perspective. This had proved to have some unexpected advantages. He could reach useful dials and switches that had previously required him to get down painfully onto his knees, and he had rediscovered long-ignored books which had languished for years on the lower shelves. The old wartime diaries were among them, their associations reviving so many half-buried memories, though his eyesight was now too poor to allow a close study.

He crept towards the bedroom on his Zimmer frame, conscious of his close resemblance to an old tortoise, his wrinkled neck sticking out ahead of his steeply bowed back. With so many aches and pains, everything was an effort. When he reached his sofa bed, he collapsed upon it while he struggled for breath.

What time did Erica usually get here? The effort of remembering exhausted him. He hoped she would come soon. His mind began to wander, making him dream of the past as he so often did.

He thought of Melancholy Jaques and his Seven Ages of Man … he had played all the parts, but now he had reached the last one. I was young too once, he thought, raising his chin defiantly. In a world so different from today, I was young.

Chapter One

Hamburg, February 1947

‘Right. That’s more than enough for one day. I’m off. See you tomorrow, Pinkie.’ I’m stiff and tired. There is just so much of man’s inhumanity to man that you can take.

The black moonscape of the ruined street is visible through the window. Dirty snowflakes fall in great swirling clusters, like dust motes under the broom of an unseen giant.

‘Righty-ho,’ he says absently. ‘Oh, better check the doors, will you, Adam? Caretaker’s not shown up again. Second time this week.’

‘It’s this ’flu that’s going round. Helga’s off as well.’

My highly efficient secretary, she of the elaborate hairdo and muscular legs, is prone to sudden inexplicable bouts of illness which necessitate her staying at home.

Pinkerton looks up at me and through me, running his ink-stained fingers distractedly through his thinning hair. He’s definitely going bald. He’s beginning to get round-shouldered too, and some days looks more like a man of sixty than thirty. He has rolled up his shirtsleeves, though the room is warmed only by a one-bar electric fire, and is peering through his wire-rimmed glasses at a closely typed document. A pot of ink and a half-drunk mug of coffee, if it deserves the name, stand at his elbow.

‘You look done in, Pinkie. Don’t you think it’s time to pack it in for the day?’

He puts his pen down and stares out at the wintry scene.

‘It feels wrong to go home when more and more of these camps are coming to light. Hundreds of them. It’s horrifying.’

I dread a long conversation. I’m so keen to get home. ‘I don’t know really, Pinkie. I’ve only been concerned with the one at Scheiden.’ I shudder suddenly, I suppose because of the hail rattling at the window. It’s getting dark now. The roofless warehouse opposite, with huge gaping holes in its walls, is turning into a grotesque face. It seems to grin at me as it merges into the shadows like a Cheshire cat.

‘New ones are coming to our attention every day. It’s quite unbelievable. Granted, I’m not talking solely about extermination camps. There were a certain number of those, I don’t know how many yet. I’m talking about KLs, detention camps, work camps. They had a staggeringly high death rate, and if the poor wretches interned in them weren’t killed or exterminated, they starved.’ He paused. ‘It seems likely to me that every town in the country of any size at all had one of these located nearby. I’m not exaggerating. Every one. And yet nobody saw a damned thing.’

‘Yes. Yes, I know.’

‘And yet we’re supposed to work with these people every day. And treat them like colleagues. I tell you, Adam, it makes me want to be sick.’

I swallow hard. There’s a point of view I want to put, and I don’t know if it has any truth in it, but I’ve learnt surprisingly quickly to regard many German people as friends rather than enemies, so I want to believe it.

‘Those numbers are staggering, I’ll admit, but be honest, Pinkie. Would the average Englishman be any different, really? We’re talking about human nature. We only see what we want to see. Don’t we?’

He cuts me off with a wave of his hand, not in the mood for my amateur philosophizing. I don’t want an argument, so I walk over and put my arm round his thin shoulders. I give him a brief hug, conscious that it’s a very un-English thing to do.

‘Good night, old man. Illegitimi non carborundum, or words to that effect.’ He manages a weak smile. ‘That’s the spirit. Good night, then. I’m off.’ He just grunts and sits down again to his files. ‘Oh, and Pinkie?’

‘What?’

‘That’s your coffee cup you’ve just put your pen in.’

Pinkie blinks at it myopically. ‘Oh, drat. I seem to do that sometimes.’ He reaches in his pocket and pulls out a cotton handkerchief to wipe the pen clean. ‘Stupid. Makes the very dickens of a mess.’

‘Pinkie, don’t you think it’s time you went home?’

‘Oh, yes, yes. I will in a while. Just got to finish this thing for Foxy.’

‘Look here, do you fancy a drink? Apparently, there’s a new bar of sorts opened near where the fish market was. Dancing and so on.’

He bends over his desk again and peers down at his document. ‘I’d love to, Adam. I would really, but not this evening. Another time perhaps.’

‘Another time, then.’

It’s hard to imagine Pinkie dancing the night away. I grin to myself and go out into the night.

The uneven pavements are slippery as I leave the relative warmth of the Kriegskriminalanlage office, hunching my shoulders against the chill. The cold wind they say comes from Russia stings my cheeks as I cut through the darkened side streets towards home, picking my way carefully through the ruins.

In parts of the city, the whole street system has disappeared. People who have lived here all their lives can no longer find their bearings. Huge piles of rubble, concrete and collapsed or derelict buildings are the new landmarks to be negotiated, where once stood houses and shops inhabited by industrious housewives and tired clerks, noisy children and grumbling grandparents. Winding cobbled lanes, with black and white half-timbered medieval houses which survived the Plague and the Black Death, have vanished forever. The delicately wrought stained glass windows, soaring roofs, and finely sculpted arches of ancient churches are now just piles of stones and blackened beams.

Broken buildings tower everywhere against the evening sky, mute in their misery. Across the whole city the many canals are still unusable, blocked with debris. Weeds grow rampant in the rubble. Their purple, yellow, blue and scarlet flowers usually provide a relief from the black, charred landscape of the burnt city, but the grip of winter has killed off their colour, and their stems, bending against the hail, are hard to discern in the gloom.

Street lighting doesn’t exist anymore, and the only illumination comes from the eerie glow of bonfires and braziers on the sites of bombed out buildings, where hundreds of the homeless shelter in the ruins. Dwellings for entire families, some surprisingly elaborate, are provided by the remains of the buildings and cellars of the houses and shops which line the once elegant streets.

In this part of the city, in some streets only fragments of buildings have survived the last days of the American and British saturation bombing, but even these provide some sort of shelter. I often pass grubby children playing merrily on the piles of rubble, sometimes acting out the actions of the planes and the noise of the bombing.

The aftermath of the holocaust is all around me. In the final days, the endless bombing created an enormous firestorm, which sucked out the air and raised the temperature to over a thousand degrees, suffocating hundreds who until then must have thought they had a chance of survival. I grit my teeth when I recall that, almost unbelievably, the Allied bombing resumed the following day, seeking to extinguish even such sparks of life that still remained. But the bombers turned away one by one. There was nothing left to destroy.

Yet a kind of miracle has occurred. Slowly, timidly, life has returned, inch by inch, breath by breath. And now, over a year since the war ended, defeat acknowledged, and an armistice signed by the broken survivors, an urban society is re-establishing itself. Food is still scarce, but mass starvation has been overcome, and fuel is becoming easier to get hold of. There is a living to be made by the able-bodied, salvaging timber from the thousands of bomb sites and selling it for firewood. The old open-cast coal workings near Thorsburg have been reopened too, and coal carts, some of them horse-drawn, have begun to appear.

A few trams are running again, and it will not be long before the former highly efficient system will be reinstated. An extraordinarily punctual bus service is already operating in the centre, though I generally prefer to walk.

Now I am passing the perimeter of the Dead City. This is the name given to the old centre, which has been almost totally obliterated. It is cordoned off and out of bounds. The destruction was so complete here that the authorities have not attempted any restitution apart from cremating some of the corpses to stop the spread of disease, concentrating their efforts on the less heavily bombed areas. Barricades of concrete blocks, decorated with crude skulls and crossbones, forbid entry under pain of death, and armed guards patrol the perimeter.

Tens of thousands of putrefying bodies still await burial within this area. The smell of death lingers. Its yellow, cloying, sickly odour is fainter now, but it never quite goes away. They say the decontamination teams which work in the Dead City have to use flamethrowers, not just on the decomposing corpses, but on the flies and the maggots which are so thick and bloated that boots slide and slip on them and impede access to the bodies. Huge green flies, as fat as a man’s thumb, are of a species never seen before. New bodies are turned up daily by the diggers, giving them plenty more to gorge on.

The hail has given way to a light stinging rain, and I wrap my army greatcoat more tightly around myself. I pull the collar up around my neck and quicken my pace as much as my stiff leg will allow, in anticipation of a hot meal and a comfortable bed. Plus there’s the cheering prospect of a drop of whisky tonight, I remember.

We are expected to wear uniform at all times, but like many of my colleagues in the services legal department, I disobey the rule as far as possible. I’ve taken to stuffing my officer’s peaked hat into my briefcase and pulling on a knitted cap when I walk through the city. Broken bricks and other debris are all too tempting for youths to toss at members of the occupying forces. French, American, Russian or English, we are all fair game to them. And I can’t blame them.

Voices are calling out to me now through the darkness from where a fire is glowing. I stop for a moment, intrigued.

‘Hey mister, got any spare change?’

‘Any smokes? Beer? Candies?’

‘Hello, handsome,’ says a younger, softer voice. ‘Give us a kiss. You want some loving? Quicktime? Just five fags? Mister?’

Then a cackle of laughter from an older woman, and a glimpse in the firelight of a girl’s face looking towards me, head tilted, a scarf or shawl tied round her long hair and shoulders. The other woman admonishes her.

‘No good, Liebchen. A young fellow like that don’t be needing the likes of you. Better stick to the married ones.’

The voices are threatening, a rumbling undercurrent of barely suppressed violence. It is a chorus from some macabre production of Macbeth, with the witches huddled round their bonfire like wild beasts growling in the background, calling curses on me, the Thane, huddled in my cape after the battle.

How now, you secret, black, and midnight hags! What is’t you do?

A deed without a name … e’en till destruction sicken.

I shiver and move out of hearing range of the jokes and jibes, keeping my head down and trying to ignore my wretched leg.

I’m glad to be home. By some fluke, the house stands proudly unscathed by the firebombing. It is a handsome house which retains a surprising degree of its former dignity. I suppose it was built by a wealthy merchant, perhaps in the late 1800s, with no expense spared. Its finely proportioned doorway and mullioned windows are miraculously intact. A smaller window is set into the mansard roof, from which can be seen a dim glow.

I walk up the worn steps to the front door, conscious of the pain in my leg. Frau Teck comes out from the kitchen as I stand in the dark hallway rubbing my hands together for warmth. She fusses nervously over me like a mother hen, helping me hang up my coat and hat and tut-tutting at how cold my hands are.

‘I was worried about you, Herr Kapitän,’ she complains. ‘You are late, and there are so many bad people about these days. They are like animals in this city. Ach, it was never like this once. It was such a peaceful place once, a place to bring up children.’

As far as I know Frau Teck has never had any children, but I let it go. Against her will it seems, her eyes are drawn to my briefcase, and then away again.

‘I know I’m late, but we are busier than ever in the office these days,’ I say soothingly, brushing the wetness off my coat.

‘I’m sure you must be.’

‘Every day more and more evil is coming out of the woodwork. Terrible crimes were committed by just a few people.’

I trot out the official line with little conviction in my voice.

‘Ja!’ she cries. ‘These criminals must be found, tried, and given the same medicine that they doled out. They are fiends. Fiends! Nothing is too bad for them!’ She starts to choke. ‘We did not know, Herr Kapitän. We had no idea. We knew there were camps, but we thought …’ She grabs my sleeve.

Here we go again. I have to put up with a lot of this from local people, and I’m finding it increasingly hard to take. Scheiden is one of Pinkie’s full-blown death camps which had ‘processed’ well over 200,000 victims during the Nazi era, and it is only a few minutes’ journey from this house. It must have been possible to smell the smoke from the crematoria here some days. There was talk by the Americans of marching citizens into some of these camps to see the evidence of what went on there with their own eyes, but it has already begun to seem pointless.

‘Promise me you will punish them!’

I take her hand gently off my coat, swallow hard, and nod mutely. This is something else I am accustomed to. But the truth – part of the truth at any rate – is becoming clear to me. We are hellbent on prosecuting the guilty, certainly, but mainly the middle functionaries of the Nazi party system, the typists, clerks, managers, and low-ranking officials, even foreign soldiers conscripted into the German ranks. Meanwhile the real villains are rapidly slipping out of our reach. Argentina is said to be awash with high-ranking ex-Nazis, with more arriving by every ship and aeroplane. But a pretence of justice has to be maintained, even amongst ourselves. The work of prosecution has to be done and be seen to be done.

‘Never mind that now,’ I say soothingly. ‘I have a little something for you, Frau Teck. Nothing much, but something.’

Her lined blue eyes look anxiously into my face, and her bony hands grip mine.

‘Some food?’

‘Just some beans, a loaf of black bread, a tin of your favourite coffee and a cabbage. A little ham. Oh, and a bottle of something that calls itself whisky.’

Her worn face lights up.

‘Oh, Herr Kapitän, that is marvellous. And the whisky you must share with the Herr Doktor. It will do him so much good. I am so much worried about him.’

‘I’ll go up to see him now,’ I say, smiling down at her. ‘I’ll eat something later. Do you think you could find a couple of your nice glasses for me to take upstairs?’

‘Of course,’ she cries. ‘I’ll bring them for you now.’

And she bustles off into her part of the house like a mouse scuttling down its hole with a stolen titbit, tail twitching with anticipation.

There is a good fire burning in the grate in the attic room where Doctor Ernst Mann lives and which he rarely leaves. A dull but adequate light from a table lamp shines onto his books on the old table where he sits working at a medical history, puffing at his pipe. On the walls are fine engravings and prints, many of his native Austria in earlier days, and some good pieces of bone china. Other books, many on philosophy, line the shelves. The heavy curtains and the sofa smell comfortingly of tobacco smoke, and Schumann’s first and only piano concerto is playing on the ancient gramophone.

The doctor quickly clears a space on the table when he sees what I am carrying, wincing slightly as he does so. He is white-haired, stiff in his movements, a little bent. For all his seventy-odd years he is active enough, though some days he looks a lot older. He seems to have aged again lately. He peers over his glasses at what I am holding, and his face now looks young again.

‘Adam! Mein Gott, that looks good. Come and make yourself comfortable.’

I have grown fond of him, perhaps needing a father figure since my own father died in the blood-soaked sands south of El Alamein commanding his regiment. Dr Mann, though, reminds me more of my late grandfather and has something of the same bookishness about him.

In many ways I prefer the company of older people. The energy of my younger colleagues is liable to get on my nerves. Their indifference, their self-obsession, the certainty of their opinions and judgements, even their optimism can be depressing rather than uplifting.

‘It’s not real Scotch,’ I say apologetically. ‘I mean, it wasn’t brewed in Scotland.’ No, you didn’t brew whisky, did you? That was beer. But we are speaking German, and the distinction is too fine for me to translate. My German is gratifyingly fluent now, although far from perfect. ‘I think it comes from Poland.’ I hold the glass up to the light. ‘It’s rather a strange colour, I’m afraid, Herr Doktor.’

He takes a deep sniff, his old face with its rheumy eyes breaking into a rare smile. There is a melancholy about the old man that rarely leaves him for long. I know little about his past, except that he left his native Austria as a young man and has served in some capacity in both wars.

He raises his tumbler to me against the firelight, though I have learnt that the Germans do not tend to toast each other. The glasses are pre-war relics from Frau Teck’s precious collection, and it is clear that we have been honoured.

‘Doesn’t smell too bad, though.’

He sips it. ‘No, not bad at all. Gesundheit! Thank you so much. You’re very good to an old man, you know.’ We grin at each other and sit in comfortable silence for a moment, feeling the liquid work its magic. The fire crackles reassuringly as a shower of sleet rattles against the window. ‘How is the world of prosecution?’

I grimace, mumbling some response and avoiding the question, and we speak for a while about the commercial life of the city. Corruption is everywhere, I tell him. The black market is thriving. The authorities have all but given up on it, but there is also some good news. A few food shops have opened up, as well as some clothing and ironmongery stores.

‘The shops are reappearing gradually. It’s a slow process, though.’

‘What are they like? I wish I could get out to see them, but my hips and this …’ He grimaces.

‘They’re not especially nice,’ I say, smiling. ‘Not a patch on what they used to be. Not like the old days. The shopkeepers don’t seem to have their heart in it somehow.’

‘You know why?’ says the doctor suddenly. ‘No Jews! We Germans don’t know how to sell, to market, to make a show. We’re going to miss our Jews.’

For a moment I am struck dumb. This extraordinary remark seems so insensitive coming from such a kindly man, seeming to imply somehow that genocide has been, well, a sort of unfortunate misjudgement. Abruptly the feeling of mild contentment induced by the alcohol is dissipated by a welter of unwelcome memories. The images related by the officer who led the first detachment to enter and occupy Märchenholz in Austria are hard to erase from the mind. They crowd in against my will. The fairy grottoes they used as torture chambers, the instruments … the doctor’s hand is on my arm.

‘I know, Kapitän,’ he whispers. ‘I know, I know. Oh God, how I know. We all have much to learn to forget. You don’t need to tell me what you are thinking. Millions dead. Millions and millions. Jews, yes, but gypsies, soldiers, the old, the crippled, children too. An entire culture annihilated. Our once proud and civilised nation defeated and the old Europe as we knew it, gone for ever. And all the handiwork of a single madman.’

The sleet has turned to rain again now. It is hammering steadily against the windows, a dull background noise in the little room. The old man stares unseeingly into the fire. When he speaks again his voice is so low, I can hardly make out what he is saying.

‘I knew him, you know.’

‘Really? You knew Hitler?’ I am incredulous.

He coughs and holds his bony hand up to his mouth.

‘I was young then. I took a job in his hometown.’

He doesn’t elaborate. After a moment I reach out and refresh his glass. The stuff doesn’t taste much like whisky, to be truthful, but any port in a storm.

‘Do you want to tell me about it, Herr Doktor?’ I ask gently.

‘I don’t know.’ He takes a sip, then puts the drink down and looks at it with longing for a moment, pulling at his long earlobe. He gives a deep sigh. ‘It was my second job after leaving university,’ he says. ‘I was still full of youthful aspirations. Young, but not too young.’ He gives a hollow chuckle. ‘I was going to do such great things. The world – what does your Shakespeare say? – was my oyster. But oysters are damned hard to open for one thing, and if you get a bad one … Ha! But I digress.’ The rain rattles suddenly against the mansards. He clears his throat and shifts in his chair. ‘Are you sure you want to listen to all this? Old men can get very tedious, you know.’ He is smiling but looking straight at me with those faded blue eyes in mute appeal. He seems to have a desperate need to talk, and for my part, I want to listen. But something is holding him back. ‘If I don’t tell somebody, I …’ He shakes his head. ‘When I left medical school I took a position with a practice in Leonding, in Austria in 1903. That is where I met Hitler.’

‘Did you know him well?’

‘Not well. He was a patient of mine. He was only a boy then, of course, fourteen or fifteen years old. But there was something about him, even then. My friend, Fritz, was his schoolmaster and knew him far better than I. Poor Fritz is dead now, but the things he told me about that boy … he became quite a talking point between us. I remember the circumstances in which I met him as if it were yesterday, and what I discovered –’

‘You discovered something about him?’

‘Oh yes. Something that only Fritz and I knew.’ He shivers a little and takes a sip of his drink. ‘It’s something that has haunted me, one way or another, for the rest of my life. I remember it was an unusually hot and wet summer, the perfect breeding ground for infection. Diphtheria, cholera … some horrific lung diseases. We were plagued by flies in the practice, an irritant in themselves, but also a source of infection. It was impossible to keep them off the patients. We had many sick that summer, especially the old and the young. The babies wouldn’t seem to stop crying. It was a busy time for me, as very heavy rains had seeped into the mine workings at the big coal pit at Bressingheim, which was a death trap at the best of times. Every day we had a quota of accidents, most minor, but some were horrific. My senior was a Doctor Bloch, and the two of us were mentally and physically exhausted. It was at the end of a long day that Adolph showed up. He had come with a letter from his father demanding cough mixture. The man complained of not being able to sleep at night. Although I was new in town, I knew his father. Alois Heidler was the senior customs official in town, a notorious drinker, a puffed-up bully. He had a nasty temper. I’d seen him a few times in the local Gasthaus and did my best to avoid him. Anyway, you can imagine how I felt, rushed off my feet looking after seriously ill and injured people, to be bothered by a demand for cough mixture, especially from someone who could solve his health problems at a stroke by giving up drink and tobacco.’

‘Yes, I can well imagine.’

‘But there was something about the boy. Something … imperious, that seemed to impel me to obey, rather than dismiss him out of hand.’

‘Even then?’

‘Yes, even then, although he was small for his age, ridiculously skinny, wearing a grubby shirt and the usual Lederhosen shorts showing a pair of pathetic toothpick legs. But for all that, he had some kind of charisma, an inner fire. You would think I’m imagining things after the fact, knowing what I know now, but it’s all written in my diary.’

‘You kept diaries?’

‘Oh yes. I started when I was about twelve and have kept up the practice all my life. It is a most useful thing for a doctor, as I not only recorded the notable incidents of my life, but I would write up medical notes too, which often were invaluable to me as a source of reference, and also a proof of action.’

‘I can see that. Do you refer to them often?’

‘Not since I retired really, but recently, well … I am an old man, and I have been going through them again. A kind of stock-take of my life,’ he sighs.

‘Did you give the boy the cough mixture?’ I ask, interested in spite of myself.

‘Yes, I gave him a bottle to loosen the cough, and also some strict instructions for his father to cut down on his pipe smoking. I charged him a few pfennigs, and as he handed over the money, I saw beneath his shirt sleeve that he had some nasty welts on his arm. I asked him what they were.

‘“Nothing!” he said, and turned red, but I insisted he took his shirt off so I could have a look. His upper back and arms were alive with vicious welts, some old and long healed, and others still a livid red. One showed sign of infection, not a surprise given the humidity.’

‘I asked him who had inflicted the wounds, but of course, I knew the answer. Terrible things go on behind closed doors, I don’t need to tell you. I put some antiseptic cream on to the infected sore, and on the others for good measure. “This is your father’s idea of discipline, I take it?” I said, but I was unsure what to do. These family matters are difficult, and it’s all too easy for well-meaning outsiders to make matters much worse.’

‘Yes, I can see that,’ I say, wondering if this is what had been haunting Ernst since meeting the boy Adolph.

‘I told him I’d like to call on him in a few days to drop off another bottle of linctus for his father.

‘“Don’t, Herr Doktor,” he said. “My family are quiet. We do not like visitors.”

‘“I think I’ve seen your sister,” I said. “I’m sure she’d welcome a caller sometimes. She’s very pretty, isn’t she?”

‘He looked at me, his eyes wild. “You stay away from her!” he shouted. “She’s – she doesn’t always know what she’s doing. You leave her alone!”

‘In spite of myself, I was afraid. There was something deranged about him. “All right, all right,” I said, raising my hands in a calming gesture. “No need to get so worked up, I’m only joking.”

‘He left, slamming the door behind him. I slowly let out a breath. I had gone quite cold, and my hands felt clammy. I was afraid, Adam. Afraid of a skinny runt of a boy. Sometimes I –’

There is a knock on the door.

‘Is that you, Frau Teck? Come in.’

The door opens, and Frau Teck makes a timorous entrance, carrying a tray.

‘Oh, Herr Doktor,’ she gasps. ‘I am so sorry to disturb you. I have your dinner here. Herr Kapitän, I took the liberty of bringing yours too. I thought you would be happy eating together.’

She brings in two plates on a tray, each holding small pieces of ham, potatoes, and some cabbage in a thin gravy. A not unappetising smell fills the little room.

The doctor and I grin sheepishly at each other, shifting in our chairs with relief now that the mood is broken. We reach for the plates and thank Frau Teck with sincerity, brushing away her repeated apologies for disturbing us.

‘It is we, Herr Doktor, who must thank Herr Kapitän for bringing us these provisions this evening,’ says Frau Teck, and she chatters away while we tuck in, praising my miraculous abilities of procurement before gently nagging the doctor that he should get out the next day for some fresh air. All the while she fusses unnecessarily about the very tidy room, folding an item of clothing draped over an armchair and picking up a stray glass and a coffee cup, then pauses briefly as she looks from one of us to the other. Then she informs us grandly that she would be taking these items to her kitchen. I feel a little guilty for not inviting her to join us, as I know she is lonely. I sense that Mann feels the same. She is a kind woman, but even in very small doses, she is an irritant. Before she leaves, she offers to bring us coffee. We both decline.

We are almost finished eating before she finally leaves the room.

‘Did you see the family Heidler again?’ I ask him.

‘Oh yes,’ he says, after nibbling a bit of cabbage. ‘I spoke to Bloch about the incident. He knew the family. Described the wife as a nice little thing, very much under her husband’s thumb. He had seen her several times over the years. She was prone to miscarriage and had lost more than one baby to diphtheria and another to measles. I remember he described them as a very unhappy family, one way or another. He had delivered the girl, Paula. It had been a difficult birth, and she had been affected mentally all her life as a result. There was another boy, too, but he had left home as soon as he was able. Not surprising really, as presumably he was subject to the same treatment as his brother.’

‘What did Bloch advise?’

‘He told me I should leave well alone, that Heidler was quite an important man in the town, and not someone I wanted to cross swords with.’

‘Well then,’ I say. ‘At least you tried. Did your duty, you know.’

He sighs and levels his eyes at me. ‘Isn’t that what you are told all the time? By people who are making excuses for themselves? I was only doing my duty.’

I put my hand on his shoulder. ‘It’s not the same thing at all,’ I say. ‘As you say, interfering with family matters can make things much worse. There is never a right or a wrong solution.’

A look of actual pain crosses his face, and he drops his brimming eyes. ‘I wish –’ he says wistfully. ‘I so earnestly desire –’

‘Yes, Ernst?’ I say, catching the note of urgency in his voice.

‘It’s not important. You do me a great service simply by listening,’ he says stiffly, suddenly clamming up, when he was so willing to talk before. ‘You must be very tired, Adam, after such a difficult day. Perhaps you would be good enough on your way down to ask Frau Teck to clear the plates away?’

I take the hint. ‘I will save her the trouble,’ I say, stacking the plates and the glasses on the tray. ‘I can drop them off to her in the kitchen on my way down.’

He presses my hand. ‘Good night, my friend. Schlafen Sie gut.’

But it is a long time before I get off to sleep, and when I do, I sleep fitfully, troubled by vivid dreams.

Knives, bloodstains, burning buildings, skeletal faces, a young strained face with burning eyes … my mother in a fur coat, calm and smiling, a dog jumping up at me demanding a walk, a dark house with empty windows … throughout it all a thread is running, in which I have to find someone urgently. It is desperately important, but buildings are crashing and disappearing into dust-filled rubble, and my legs won’t move and I can’t run … there is a girl with soft arms around me, but she slides silently away, leaving me cold and naked and alone again.

Then I am back on the beach with the sound of shellfire, missiles exploding overhead, the smell of the sea in my nostrils and the taste of vomit and fear in my mouth …

Chapter Two

Normandy, June 1944

It was the morning of my twenty-fourth birthday. If the world were running to order, I should have been celebrating my graduation from Oxford.

I had very much wanted to read English Literature and German, but my father had insisted on my following in his footsteps as a lawyer. Perhaps just a gentleman’s degree, announcing to the world you had proved to be neither a perfectly beastly swot, nor yet a drunken wastrel, but a law degree nonetheless and something to celebrate.

A formal party would have been held at my family’s seventeenth-century home in Chipping-on-the-Fosse, all mellow golden stone and shaven lawns. The gently weeping willows at the bottom of the long garden would be maintaining their proprietorial watch over the little river Windrush as it burbled merrily along, bustling with brown trout and the occasional snapping pike, midges dancing in the sunlight. I would have been joined by my contemporaries, sons and daughters of solicitors, doctors, land agents and perhaps even the lesser landed gentry of our social circle. The company would have been rowdy and confident, the girls, oh so fetching in their sleeveless dresses showing off sun-kissed skin, laughing together as they brushed their hair off their faces. My mother would have looked worried but still beautiful in her weary way, determined to make the party swing, knowing all too well what Fate might await the young men. She would be fighting back tears as she thought of how proud my father would have been.

But that was all make believe.

Instead, I had still not finished my degree, and on my birthday, I was otherwise engaged. To be precise, I was leaning over the deck rail of a very small, battered ship, retching over the side and wishing myself dead. I had felt horribly sick within minutes of embarking from Portsmouth and had to organise my men during the five-hour voyage across the Channel while fighting off nausea.

When we got to France, we had to transfer from the ship onto a flatbed landing craft, a dangerous operation, and unbelievably, the swaying motion of the clumsy craft was even worse for my seasickness than the ship. The thing lurched clumsily towards the beach like a drunken sailor staggering out of a dockside pub on payday. I prayed for a friendly bullet just so the nausea would stop. I staggered towards the rope ladder on the side of the flatbed, pack and rifle impeding my movements. I snarled orders at my men who were clumsily following me. One of them swore at me and I pretended not to hear. My guts were churned by fear as well as seasickness, and in that desperate reality, my lofty rank of lieutenant was forgotten.

The flatbed staggered into a setting straight from the imagination of Hieronymus Bosch. There were literally thousands of men on the wide sandy beach, all surging forward under a blistering hail of machine gun and shellfire from the gun emplacements ahead. Dozens of German planes were sweeping overhead and strafing the beach and as I watched, two nearly collided with each other. As they hit the various munitions stores on the beach, spurts of sand in enormous explosions shot high into the air.

I looked over the bows of the unwieldy, swaying craft. Three hundred yards away a body of men was clustered round a large Bofors gun which had been dragged ashore. Maybe we should join them, perhaps to help move the gun further inland.

But even as I was looking in their direction, with my eyes narrowed against the spray, they were hit, and mangled bodies flew through the air in an acrobatic display amid flame and fire and flying debris. When the sand settled, all that remained were body parts, some still writhing. The men had been obliterated before my eyes and there was little left to be seen of them. They might never have been. The big gun lay uselessly on its side. My own troops muttered together at the sight, then fell silent. In every man’s mind the same thought was predominant. It could be me next.

The craft lurched crazily again, still not beached. I shook my head, blinked and wiped the salt spray away. Oh God, this is the end of me, let it be the end, goodbye, goodbye, let me die now.

I retched emptily for the umpteenth time, at the very moment when the flatbed hit the shore with a bang. It shuddered, then settled jerkily onto the sand. All around us, the sea was churned up by dozens of vessels, considerable stretches of the water more scarlet than blue. Bodies, some still showing signs of life, bobbed everywhere in the water.

Angrily I wiped the traces of sick from my mouth with the back of my hand and stepped unsteadily off the ladder onto dry land. I was screaming something unintelligible above the noise of the bombardment, blindly waving my men forward.

I stopped for a moment to grin at a white-faced boy beside me, clapping an encouraging hand to his shoulder. The young soldier stared back at me, his eyes wild and rolling in his head. He was holding his hands to his chest. He opened his mouth to speak, and then slowly sank to the sand.

I couldn’t stop to help him as we surged forward. I looked around for Peter Pullan, my company commander, for orders. Where the hell was he? He was meant to be in charge of this bloody landing. We had had a muttered conversation ten minutes earlier, Peter shaking his head and saying something quite out of character in his quiet voice about the whole thing being a cock-up. But now there was no sign of him.

There was no time to consider anything. The noise on the shore was indescribable, and bullets were hissing into the sand round me. Now that my nausea had at last abated, I ordered the men as far up the beach as we could go.

I turned to a squat ugly little miner from the Valleys who grinned back at me. Rogers, that was his name. He had a wonderful tenor voice. What was it he sang at the regimental concerts? ‘Hand me down, my silver trom-pet …’ Glorious.

‘Rogers! Come on!’ I yelled. But as I looked, Rogers’ arms and head went one way and his lower half another. Blood, brains, and guts sprayed the air. Rogers and his sublime voice were gone forever.

I ducked away, wiping unspeakable grey and red matter from my face. Crouched low against the suddenly renewed hail of machine gun fire, I ran, my pack banging against my back. I pounded on and on, in a desperate primeval need to survive, just to get through this hail of death to some kind of safety. I kept ducking stupidly, as if I could avoid the bullets by going under them.

There was a brief, unpredictable lull in the firing, and I felt myself able to think again as the noise abated. I steadied myself, somehow gaining ground uphill. I was panting hard enough to burst my lungs, but I dared not stop, pressing on, flooded with the desperate need for self-preservation.

After a moment I looked round. Some of my men were following just behind me. I ordered them on with a wave of my hand. We reached some sand dunes on upward-sloping ground, an area covered with spiny grass, painful to the touch and covered in sea urchins and seaweed, no doubt covered at high tide. By chance, we had found a kind of haven, a dip in the ground where in happier times a family may have taken a picnic, or children kicked a ball around on a sunny day at the seaside.

Behind me up the slope came my contingent, or what was left of them. I motioned them to get down, and they needed no encouragement. I realised with a horrible sense of shame that they had been following me, blindly trusting me as their leader, while in truth I had been fleeing for shelter to save my own skin. I gulped and tried to speak, raising my voice against the barrage on the beach further below them.

‘Well done, men,’ I croaked, struggling to find some words of encouragement, too breathless to say any more. ‘We’ve got through the worst. Who’s the senior NCO here?’

Most of the men were lying flat on their faces gasping for breath, but now they looked around at each other to see who had survived. Out of nowhere a shell landed with a tremendous bang twenty feet away, and we all ducked again.

‘Sergeant Lang here, sir,’ said a voice from the ground. ‘But I don’t know if I’m the senior. And Lieutenant Milne was leading a party just behind us. He should be coming up any minute if they’ve got through.’

‘All right, sergeant,’ I said. ‘What do you reckon, then?’

‘Think we’d better push on up and over this hill, sir,’ said the sergeant, beginning to crawl over the spiky grass towards me. He was revealed as a long, thin individual, with a permanent expression of wry amusement. Absurdly, I remembered him now from a camp concert in Portsmouth at the barracks, where he’d played a pantomime Dame to great applause.

‘We’ve been lucky, sir. Just come through a gap. I suggest we get the hell out of it, sir. We can get behind the Jerries and shove on into town while their attention’s on the beach.’

We both looked down on the devastation beneath us. We had a bird’s eye view of a good part of the invasion. A hundred and fifty thousand men had landed on the beaches that day, I was to learn much later, the biggest invasion in the history of the world. Nearly seven thousand ships took part. Ten thousand men were to die where families played and children swam in peacetime, where the sea was now churning so full of bodies that it had turned scarlet.

And at that particular moment, as the fate of Europe and the course of the greatest war mankind had ever experienced was about to be determined, the ridiculous realisation dawned on me that I hadn’t been shot. I didn’t feel sick anymore. I was young and alive and abroad and it was my birthday, and the Allied invasion of Europe had finally begun.