6,49 €

Mehr erfahren.

- Herausgeber: WriteLife Publishing

- Kategorie: Poesie und Drama

- Sprache: Englisch

Using God's gift to be accepted...

John Byner is a man of many voices and characters, from impersonating the slow, rolling gait and speech of John Wayne, to lending his voice to The Ant and the Aardvark cartoons. His dead-on impersonations, as well as his unique talents as a character actor, have put him on the small screen in peoples' homes, the big screen in theaters, and no screen on Broadway.

Growing up in a big family on Long Island, John discovered his uncanny ability to mimic voices as a child when he returned home from a Bing Crosby movie and repeated Bing's performance for his family in their living room. He discovered his talent made him the focus of everyone's attention, and allowed him to make friends wherever he went, from elementary school to the U.S. Navy.

John started his career in nightclubs in New York but soon found himself getting national acclaim on The Ed Sullivan Show. With that he was on his way.

This memoir is the best and funniest moments of his life, career, and relationships with some of the biggest names in entertainment, both on and off the screen.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2020

Ähnliche

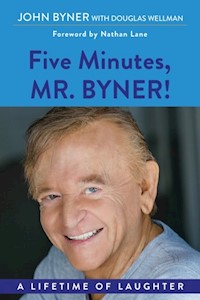

Five Minutes, Mr. Byner! A Lifetime of Laughter

© 2020 by John Byner with Douglas Wellman. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

This story is told from the author’s experience and perspective.

Published in the United States by WriteLife Publishing

(an imprint of Boutique of Quality Books Publishing Company, Inc.)

www.writelife.com

978-1-60808-234-6 (p)

978-1-60808-235-3 (e)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020937558

Book Design by Robin Krauss, www.bookformatters.com

Cover Design by Rebecca Lown, www.rebeccalowndesign.com

Douglass Wellman author photo by Alisha Shaw

First editor: Michelle Booth

Second editor: Olivia Swenson

DEDICATION

I’ve been fortunate to have a long career in a business I love. I’ve met wonderful people and developed enduring friendships, but when it comes to dedicating this book there is a special group I want to acknowledge: my family. I thank my talented wife, Annie Gaybis, for being at my side as a constant source of encouragement (and a lot of laughs). My children, Sandra, Donald, Rosine, and Patricia, are spread across the country, but always in my heart. I’m a lucky man.

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments

Foreword

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

About The Author

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Beatles once said, “I get by with a little help from my friends.” Well, that goes double for me. I want to thank the following people who helped with the preparation of this book by providing pictures, dates, and a little help when my memory stalled out.

Joanna Carson – for pictures and memories of my appearances on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

Andrew Solt – who holds The Ed Sullivan Show recordings, for the use of pictures and research assistance.

Vincent Calandra – talent coordinator on The Ed Sullivan Show, for helping me get in touch with some of the people from the show and reminding me of our good times back then.

Steven Alexander – friend and computer expert, both of which I appreciate.

I’m grateful for your assistance.

John and Nathan Lane from “The Frogs.”

FOREWORD

by Nathan Lane

The immortal Sid Caesar once said, “Comedy has to be based on truth. You take the truth, and you put a little curlicue at the end.”

And I suppose if you have enough curlicues, you’ve got an act.

There are so many comics these days, of all shapes and sizes and ethnic groups and sexualities and genders, in so many venues, from clubs to YouTube videos to podcasts to that perilous domain known as Twitter. So much so that it can be difficult to keep up with all the talented new original voices. It’s hard to remember back to when there were only three major networks, and one boffo appearance on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson could possibly change your life.

Let me come back to that.

It’s 2004 and the phenomenal director/choreographer Susan Stroman and I were taking on an ambitious project at Lincoln Center Theater. I had always been fascinated by the musical version of The Frogs, which in its original form was the big hit play of 405 BC by Aristophanes. The musical was written by the wonderful Burt Shevelove and the incomparable Stephen Sondheim. They had very successfully and famously collaborated on A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum. The Frogs, however, was a very different animal—or slippery amphibian, shall we say—and because of its mixture of highbrow and lowbrow comedy, satire and political commentary, it made it an extremely tough nut to crack. In fact, when it was originally done in 1974, in the Yale swimming pool no less, it was not well received.

I wish someone had mentioned that to me.

Steve also said that because of the difficult acoustics, “It was like trying to perform a musical in a men’s urinal.” And I was not only starring in it, but doing a new adaptation of the book as well. What on earth was I thinking? I guess I was thinking I love a good challenge. Not to mention we were in a very politically divisive time in our country. Sound familiar?

Anyway, I had created a dual role for an actor—Charon, the pot-smoking, unflappable boatman on the River Styx, and Aeakos, the ancient and hearing-impaired guard at the gates of Hades. My initial inspiration for the part was Tim Conway and his “the Oldest Man” character on The Carol Burnett Show, which had always killed me. We inquired, but Mr. Conway was on a comedy tour with his best audience and co-star Harvey Korman. I kept thinking the part needed not just a good actor, but a great performer with a history in comedy and improvisation.

And then someone suggested John Byner. Or maybe I suggested him, I can’t remember now. But the minute I heard his name, my eyes lit up. When I was a kid, my two older brothers, Dan and Bob, and I would always stay up late and tune in to The Tonight Show if John Byner was the guest. We loved John Byner like he was a sports hero, although I don’t really follow sports, but there was no doubt he was a heavy hitter. He always seemed so relaxed and hip and full of fun and mischief. And he could make Johnny laugh. That was a big deal. I mean, really laugh, like prolonged laughter, where he threw his head back and twirled a little in his desk chair in delight.

The only other guests at that time who could make Carson laugh that hard were the legendary Don Rickles and Jonathan Winters. So, John Byner was in very rare company indeed, and it seemed like every appearance he had on The Tonight Show was boffo, at least at our house.

Also, John was, and still is, a sensational impressionist. And whether he was reminiscing about a local parish priest serving mass in Latin, who looked and sounded uncannily like John Wayne—“Aw, Dominus vobiscum!”—or demonstrating the hilarious break in Johnny Mathis’s romantic singing voice, or becoming Ed Sullivan on his classic Sunday-night variety show running short on time and rushing everyone through their acts, like the Barzoni Brothers, Italian acrobats cut down to just one Barzoni apologizing in a thick accent—“It’s not the same without my brother!”—or topping that, Ed Sullivan getting angry on his last show and saying everything he ever wanted to say, especially to the little Italian mouse, Topo Gigio, or memorably voicing the animated show The Ant and The Aardvark, where the ant sounded disturbingly like Dean Martin and the aardvark turned out to be a very excitable Jackie Mason, John’s brilliance always shone through and knocked us out.

Perhaps his best and most popular impression back then was of veteran twentieth-century entertainer George Jessel. Often referred to as the Toastmaster General for his work as a master of ceremonies—“The Al Jolson funeral was widely attended by people just wanting to make sure”—he started in vaudeville and worked as a comedian and singer for many years. It’s difficult to explain someone like George Jessel today. It’s like going to the Museum of Natural History and pointing out the differences between the Cro-Magnons and the Neanderthals, but let’s just say he was in the Al Jolson and Eddie Cantor category, if that rings a bell, telling ethnic jokes and singing schmaltzy songs like “My Mother’s Eyes.” I realize I’ve been dropping a lot of forgotten show business names, but please remember Google is your friend.

To say George Jessel was eccentric is an understatement. He often wore a military uniform on talk shows, maybe because he was the unofficial Toastmaster General, maybe because he used to entertain the troops during the Vietnam War, maybe because his good suit was in the dry cleaners, who the hell knows, and he had enough vocal and facial tics to initiate a set of clinical trials. Not to mention an incontrovertible toupee that looked like a tree monkey had fallen on his head and died of shock. Vocally he sounded a little like the love child of Buddy Hackett and Adam Sandler. Yikes, that’s a troubling image I won’t be able to get out of my head.

And yeah, I know, who’s Buddy Hackett? I don’t have time for all these questions, I’m writing a foreword for John Byner!

Anyway, John did this riotous and impeccable impression of Jessel, especially elderly Jessel, who, the older he got, became harder and harder to understand. Whatever noise was coming out of his mouth resembled someone trying to gargle in Yiddish while finishing an onion bagel. Okay, you had to be there. But John did this to perfection, and Carson would split a gut giggling, while the Lane brothers roared in Jersey City.

So I got Lincoln Center to offer him the part in The Frogs and got to work with one of my comedy heroes.

John went on to give an outstanding performance in the show and got singled out in all the reviews for his masterful deadpan comedy. He was a total pro and couldn’t have been sweeter or more gracious, even when things weren’t going so well.

During the run, before a matinee one afternoon, I said to John, “Just for fun today, why don’t you play Aeakos, the very old guard, as George Jessel? See if it works and we’ll have a few laughs.” John looked at me nervously and said, “Really?” And I said, “Yeah, what have we got to lose?” So John said, “Don’t you want to rehearse?” And I said, “No, surprise me.”

Cut to me knocking on these huge doors, they slowly open, and this little old man with long gray hair and an even longer beard steps out and starts talking like George Jessel. And it’s uproariously funny. Unfortunately, even the prehistoric Lincoln Center subscribers, people who probably went to high school with Aristophanes, don’t seem to remember George Jessel at all and remain silent. Perhaps even slightly puzzled that this guard from Hades sounds so, well, Jewish. Only one person is laughing and that’s the great Paul Gemignani, our conductor and musical director, and he’s beside himself. He was also a big John Byner fan and recognized immediately who he was doing. Then I started laughing, not just because of John’s terrific impression, not just because Paul was in hysterics, but because I realized for the next few scenes John would have to continue being George Jessel. That absurdity really got me. Dear departed Georgie would have been so proud to know he was being resurrected on the Great White Way.

Later one of the young members of the ensemble asked me why the old guy was talking so funny at the matinee. I told him he may have had a stroke. Kids!

Obviously, John has had a remarkable career spanning decades, from doing comedy in small clubs in Greenwich Village to The Ed Sullivan Show—John will explain, Ed loved him—to The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson, to Steve Allen, who basically invented the talk show, to The Carol Burnett Show, to just about every major variety show or situation comedy there was on the air, to hosting his own variety show and introducing Bob Einstein as Super Dave Osborne, and on and on. But I’ll let him tell you about all that.

And he’s still going strong, as funny and as kind as ever. That’s the truth without a curlicue.

Nathan Lane

Los Angeles, July 20, 2019

Chapter One

I (Do) Know Jack

Some people call it fate; others call it luck. Whatever you call it, you’ve probably been somewhere by chance at exactly the right moment and ended up getting a welcome surprise. I had one of those moments early in my career and it changed my life.

My ability to mimic voices opened up some special opportunities for me. Initially It was just a hobby. I entertained family members, school mates, buddies in the navy, and my coworkers in a myriad of blue-collar jobs, and one white-collar one. I had no idea my future would be in the spotlight in night clubs, television, cartoons, movies, variety shows, and a host of other exciting places. And maybe it wouldn’t have been except for fate, luck, or whatever you want to call it. My world opened up one night because I happened to be on a little stage in New York at just the right moment. It was an unplanned event. Had it not occurred, I don’t know where I’d be today.

When people think of the New York entertainment scene they usually think of Broadway. Broadway is more than just a street, it’s a name that has become synonymous with the entire Theater District, and theater in general. While Broadway is the home for performers who are at the top of their game, there’s a little area on the West Side of Lower Manhattan called Greenwich Village that has been the launching point for many a talented individual on their way up. It’s several square blocks that most non-New Yorkers couldn’t find on a map, but the name conjures up an aura of art, music, and counterculture to people all over the world. Greenwich Village “The Village” is a big deal.

In the ’60s The Village was the place for me. Just below 11th Street on 7th Avenue South stands the Village Vanguard nightclub. Actually, it doesn’t really stand, it kind of sinks. It’s in a basement at the bottom of a dark, narrow staircase. My friend O. C. Smith once said, “You don’t walk into that club, you fall into it.” The space had been a Prohibition era speakeasy, but the end of Prohibition was bad news for the speakeasy business. This presented an opportunity for a man named Max Gordon. He leased the abandoned speak, got a legal liquor license, and went into the nightclub business in 1935. Keeping with the offbeat neighborhood culture, you could see almost anything on the Vanguard stage. Early on there were all styles of music and practically every other performing art, including poetry readings. Then came the bebop musicians and hipster artists of the ’40s and ’50s. Folk singers like Pete Seeger, Peter, Paul and Mary, and Burl Ives played the room. A young calypso performer by the name of Harry Belafonte got an early break there, as did jazz queen Eartha Kitt. I don’t know if a professional yodeler ever played the room, but it wouldn’t surprise me. Max liked comics, too, and Lenny Bruce, “Professor” Irwin Corey, and Wally Cox all played the Vanguard on their way to fame. The Vanguard is a big deal. It’s especially a big deal to me, because in February of 1964 I was performing on the famous Vanguard stage.

The Vanguard isn’t a big room. When you walk down the stairs you see a long, padded bench along the wall to your left, with a line of small cocktail tables. A few more tables are scattered in the middle of the room, with an open space for dancing. The bar is on the right. Dead ahead is a stage that seems ridiculously small for the size of talent that stands on it. They say good things come in small packages. That’s the Vanguard.

In the early ’60s the Vanguard was beginning a transition toward being primarily a jazz club. Like some of the other New York music rooms, the Vanguard would book comics to take the stage while the musicians were on a break. This worked out pretty well for me, since my manager, Harry Colomby, managed a couple of big jazz acts and had all the connections to the clubs. Max Gordon usually took a look at the performers before they got a shot at his stage, but in my case he took Harry’s word for it that I was good enough for the room. I was always well received by the customers at the Vanguard so Max was happy. I was certainly happy and Harry was at least 10 percent as happy as I was.

You could see just about anything on the streets of the Village back then, which meant just about anyone could wander through the front door. After my set one night, Harry and I hung around for a quick drink. Afterwards I said goodbye and went to pick up my raincoat on the coatrack near the front door. It was gone. We spent a couple of minutes looking for it, but it was pretty clear that it had been stolen. As I was getting ready for a chilly walk to my car, there was a phone call to the office and a guy said, “If you’re missing a raincoat, it’s rolled up and in the doorway of the closed gas station across the street. It didn’t fit.” My lucky day—a considerate thief who wasn’t my size.

I worked the Vanguard for the better part of a year, which was my longest ever club date. The audiences ranged from beatniks to businessmen, so I got to meet a lot of different people. One night I met a guy named Jack Babb. It was a brief conversation with lasting impact. Jack was the talent coordinator for The Ed Sullivan Show, and on 1960s TV Ed Sullivan was the biggest deal of them all.

In some ways The Ed Sullivan Show was like the early Vanguard. It was a variety show with no specific style of entertainment. If Ed thought someone was entertaining, no matter what they did, they had a shot at getting booked on the show. On any given Sunday night you could tune in and see a Broadway star and an opera singer, followed by a guy who spun plates on a stick. This strange format was genius back in the days when there were only three TV networks. If the viewer didn’t like the act that was on they didn’t turn the channel. They didn’t have to; something different would be on soon. This TV free-for-all appealed to a huge audience and could make, and in a couple of cases break, careers.

Jack Babb was a distinctive man and a class act. He was about sixty years old and dressed like the cover of GQ. He had one of those low, rumbling voices that made everything sound important, whether he was reciting script notes or a restaurant menu. He wanted Sullivan to see me, and the best way to do that was for me to go to the theater on show day and perform in the dress rehearsal. This audition would be as close to the real thing as you could get. Jack laid out the prospects fairly simply. “If the old man likes you, we’ll give you something in the future.” Fair enough. It was Thursday and the dress rehearsal would be the next Sunday afternoon. That gave me almost three days to organize my best material, rehearse, and not let my nerves get in the way.

Sunday finally rolled around, so I put on my one and only suit, and drove from my home in Baldwin, Long Island, to pick up Harry in Forest Hills. It was a big day for both of us, since having one of his acts on the Sullivan show would boost his image as a manager. A rising tide lifts all boats, as they say. As we drove into Manhattan we talked about which bits I should use in my set and generally had a few laughs and a pretty good time. The car radio was playing softly in the background and Harry suddenly shouted, “They’re ruining good music!” I said something like, “Huh?” and Harry twisted the volume control up until I heard the very distinctive voice of Joe Cocker singing “Cry Me A River.” The song had been a huge hit when sung by the sultry Julie London, and jazz purist Harry was having nothing of Joe’s guttural growl. He acted like he’d been poked with a cattle prod and I had to laugh at his reaction. Joe Cocker later became a good friend of mine. I don’t know if Harry ever became a fan.

It took about twenty-five minutes to make the drive to the corner of 53rd and Broadway, a place that was then called Studio 50, but is now named the Ed Sullivan Theater in Ed’s honor. It was around one o’clock when we parked around the corner and went into the theater looking for Jack. With 720 seats, the place was a pretty good size for comedy. Stand-up is intimate, so it’s nice to have the audience close enough to see the expression on your face. The television cameras, microphone booms, and small army of staff and technicians milling around the scene were pretty impressive, but all the commotion was a bit unnerving. To ratchet up the tension level even more, the show wasn’t recorded for later playback, it was broadcast live to TV stations around the country where millions of people watched as it happened.

Jack spotted us, greeted us, and gave us a brief outline of what was going to happen. Since I used music in my act, the first thing I needed to do was have a conference with Ray Block, who did the musical arrangements for the show and conducted the orchestra. Once we got the musical keys worked out, Jack took us upstairs to my dressing room where we got away from the pre-rehearsal commotion and I had a chance to focus on what I was going to do. We didn’t sit too long. By two or three o’clock it was rehearsal time and I was on.

I went downstairs, got a few basic instructions from the stage manager, and waited for my cue. Honestly, after all these years I can’t remember exactly what impressions I did. I had my music, so I did Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin. I probably did John Wayne—always a big hit in the clubs—and I certainly did my Ed Sullivan. Other than that I don’t really recall. I guess I remember the overall experience of the lights, cameras, and big TV studio setting as a whole more than individual bits. I finished my set to applause and headed back upstairs to my dressing room feeling relieved and pretty good about the whole thing. In a few minutes there was a knock at the door and Jack walked in with a smile.

“Hey,” he said. “The old man likes you. You go on tonight.”

Tonight?!

Fate, luck . . . whatever you want to call it, I’ve had my share. There’s a lot of great talent working the hotel lounges of the country only because they didn’t get the break required to move up the line. Jack Babb’s decision to stop by the Vanguard that night was the bit of luck I needed to give my career a boost. If that hadn’t happened, maybe I would have gotten another break, or maybe I wouldn’t have. Who knows?

Here’s a big surprise for you: life can be difficult. Oh . . . I guess you knew that. Everyone has their ups and downs and I’ve had mine, too, but you’re not going to read about them here. You have your own problems; you don’t need to hear me complaining about mine. Besides, that’s what the National Enquirer is for. No, I’d rather talk about the good things in life, the fun things, the uplifting things. I’ve had an exciting life among fascinating and talented people, and I’m still out there having a ball. I’ve had a lot of laughs. That’s what I want to share with you. In the world of entertainment, some of the funniest and most fascinating things happen in places the audience never sees. I’m going to take you there.

This will also be a bit of an entertainment history book. Although I was still pretty young, I got to work with some of the pioneers in television, like Ed Sullivan and Steve Allen. Variety shows were popular for a long time and I shared stages with Bob Hope, Bing Crosby, Glen Campbell, Andy Williams, Sammy Davis, Diana Ross, and on and on. I even had a variety show of my own. I was a cast member on the offbeat sitcom Soap, and made thirty-seven appearances on The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson, when Johnny was the undisputed king of late-night television. There was no such thing as a bad Tonight Show. Las Vegas was still in its relative infancy, but its showrooms drew the best of the best. When you drove down the Strip you saw real entertainers, celebrities who were so big they only needed one name: Frank, Dean, and of course, Elvis. I was there and I got to be a part of all of it, and for that I’m grateful.

So, I’m going to share some stuff from my life and the great people I’ve been blessed to have in it. But just the good stuff. In the end, that’s the only stuff that really counts.

Chapter Two

Kid Stuff

I came from a normal family. I hope that doesn’t disappoint you. A lot of celebrities go on talk shows to discuss their books and whine about their abusive father, alcoholic mother, or uncle who lived in the attic and practiced the bugle. I don’t have any of that. If there was any disadvantage in my life, it was being the fifth of six children who were all competing for the affection of our parents. I really can’t complain about that either, since that was part of the motivation for developing my voice talents.

My father’s name was Michael Biener, but the family name was originally Buehner. Somewhat prophetically, the name means “stage.” In the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, the United States was the place to go. It seemed like the whole world had tilted and everyone who wasn’t attached to a good life in their own country slid toward America. They landed in a pile on Ellis Island in New York Harbor where all immigrants from Europe were processed. So it was with my grandfather, John Buehner. He earned his passage to the United States by working as a ship’s cook. He was born in Biene, Germany, in 1887, so he apparently either decided to honor his hometown by changing his name from Buehner to Biener, or someone in immigration decided to do it for him. With his new country and new name he set out on a successful career as a carpenter. He was also pretty successful as a family man, fathering six children. He died in 1937, the year I was born, so I never got to know him.

My father was a great guy and something of a mechanical genius. I think he probably could have taken a handful of paperclips and turned them into an engine. That was his real talent; he was a wizard with engines. When I was young we lived in the Laurelton neighborhood of the borough of Queens, where he made his living as a truck mechanic for Queens County. He left that job when we moved to Merrick, Long Island, for about a year, the first of several moves. Dad’s golden touch with engines drew the attention of the car racing community, who used his talents to tune their cars. They’d haul them out to him on flatbed trucks, and he’d tweak the engines until they reached maximum power. He was lucky to have a career and a side business doing what he truly enjoyed.

My parents kept a secret from us kids to save us from worry. Dad was ill, but we didn’t realize it until he became unable to work. Even then I don’t think we realized the seriousness of the situation. My three oldest siblings had started lives of their own and were no longer living at the house, so our parents decided to move us out farther on the Island to Bohemia. There they purchased five acres of land with two houses on it for $5,000. Try making that deal today. We lived in the front house and rented out the other, but finally sold the front house and moved into the back one. This turned out not to be such a great idea. The back house was really just an uninsulated summer house and not adequate for the cold Long Island winter. We ended up huddling around an old oil stove in the living room, which was inconvenient, but oddly enough, it’s one of my favorite childhood memories. Dad was a great guitar player and he had taught Mom to play the mandolin. That winter became a family song fest with all of us gathered around the stove, singing and generally having a ball. That happy time really brought us together as a family. When Dad died shortly thereafter at the age of forty-six we were all devastated.

Dad’s death triggered another move. Mom still had three kids at home to feed and raise, so she couldn’t just sit around and mourn. She solved the immediate problem by accepting an invitation from our Aunt Annie and her husband Joe to stay with them in Elmhurst, Queens. There my brother Tom and I went to PS 89, and our sister Christine went to Newtown High School. Mom’s first job in Queens was working nights at Bellevue Hospital. Soon she was able to put some money together and we were able to move into a one-bedroom apartment in a new building. It was only six blocks from PS 89 on McNish Street and a block from the 8th Avenue subway line. Mom and Christine took the bedroom and Tom and I shared a couch that pulled out into a bed. That was just fine with us.