10,00 €

Mehr erfahren.

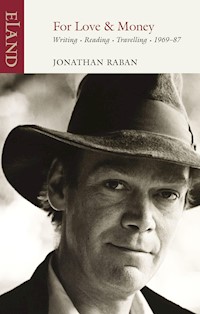

- Herausgeber: Eland Publishing

- Kategorie: Sachliteratur, Reportagen, Biografien

- Sprache: Englisch

This collection of writing, undertaken for love and for money, is largely about books, writers and travel. It is an engrossing and candid exploration of what it means to make a living from words.Jonathan Raban weighs up the advantages of maintaining an independent spirit against problems of insolvency and self-worth, confesses to travel as an escape from the blank page, ponders the true art of the book review, admires the role of the literary editor and remembers with affection and hilarity events from his eccentric life at the heart of literary London. Reading it is like eavesdropping on a humane, rigorous and witty conversation.

Das E-Book können Sie in Legimi-Apps oder einer beliebigen App lesen, die das folgende Format unterstützen:

Veröffentlichungsjahr: 2018

Ähnliche

For Love & Money is one of the most honest and revealing books about the practical realities of writing for a living ever committed to print and should be read by anyone tempted to labour in what George Gissing called the Valley of the Shadow of Books.

D. J. Taylor

His writing articulates a style of humane and witty conversation: he excels at the revealing anecdote, the smart phrase, the art of happy extravagance. And by being perhaps the only critic of calibre who is not an egomaniac, his judgements emerge as the elegant ponderosities of an intelligent reader – and not from a critic at all.

Roger Lewis, Punch

You see with pleasure how reading has shaped without subduing his style. Raban is never guilty of supposing that he can use lower writing powers because what he’s doing is only journalism. The splices are excellent. Raban is interesting everywhere.

Frank Kermode, London Review of Books

A marvellously absorbing anthology which leaves you eager for Raban’s next haul of sightings and soundings.

Times Literary Supplement

A marvellous writer. On books and travel he is spellbinding.

Sunday Times

The high standard of the writing apart, the book is distinguished from the typical grab-bag by the use of a running commentary on the life of a writer-on-the-make in London. It is so cleverly concocted, so replete with battered affection for the writer’s trade…

James Campbell, Guardian

For Love & Money

Writing • Reading • Travelling 1969–87

JONATHAN RABAN

To my parents, Peter and Monica Raban

Contents

I

THIS IS PARTLY A COLLECTION, partly a case-history. I’ve clocked up nearly twenty years as a professional writer, and in that time I’ve made the intimate acquaintance of all of Cyril Connolly’s enemies of promise, with the sole exception of the pram in the hall. I’ve written out of compulsion, for love, and I’ve needed the money. It is a curious occupation, this business of short-distance commuting between the bedroom and the study, and a subject in its own right. It puzzles people. Strangers at parties, striking up a ‘literary’ conversation, don’t (usually) want to haggle over the contents of your review of Martin Amis in last week’s Observer, let alone whether your most recent book got off to a bad start in the first chapter. They have quite probably read neither, but they’re still interested. They want to know whether you use a pen or a typewriter, what time you get up in the morning, whether you keep regular working hours, whether you can really make a living from it and – the big clincher – exactly what and how you get paid. Average-adjusters, lecturers in economics, shoe salesmen, property developers, don’t wince, shuffle and gaze distractedly at the ceiling when someone politely asks ‘And what do you do?’ For the professional writer that question (which is quickly followed by ‘Oh, should I know your name?’) is the prelude to a searching catechism of a kind more appropriate to a VAT inspector than to a fellow-guest in a drawing-room. The safest response to it, if you can summon the requisite bottle, is to say ‘I’m a steeplejack’ and beam ferociously.

Alternatively, you might answer the catechism by hauling your surprised questioner off for a weekend to give them the works – the hours, the commissions, the block, the aborted beginnings, the continuous themes that slip from fiction to non-fiction and back to fiction again, the double-spacing, the advances, expenses, public lending right, royalties, and the editorial advantages of using wide margins. Part of this book consists of blue-pencilled scenes from that weekend, because the questions are worth answering. Conditions on New Grub Street change with every generation. The world originally described by Gissing in the 1880s connects with, but is significantly different from, the world described by Cyril Connolly in the 1930s and ’40s. Mine, in turn, is different from Connolly’s; and someone now in their twenties, setting out as a professional writer in the late 1980s, would encounter a working world much changed since I first knew it in 1969. This is a particular story, of someone born in 1942 who wanted to be a writer and found himself working in a very specific set of industrial and economic circumstances. How did he come to get the job, and what sort of a job is it?

I was eight or nine when I knew that I was – in the merely occupational sense of the word – a writer. It was a knowledge founded on no evidence at all of any special verbal or imaginative talent. Yet it was a fact, just like the fact that I was asthmatic. I was a writer. More precisely, I was an author. For writers, or so I supposed, actually did quite a bit of writing, moving fast from one piece of paper to the next. Authors were as immobile as waxworks. They sat at desks in photographs. The paraphernalia of their trade – expensive fountain pens, gilt-edged blotting pads, silver inkwells, marbled notebooks – were arranged in tasteful still-lives in front of them. They had the glossy hair and jutting chins of matinée idols. They were – oh, A. E. Coppard, Edgar Wallace, Michael Gilbert, Nevil Shute, H. E. Bates – and I could feel the glow of their fame radiating out from their pictures to include me.

It was what I was going to be: a personage in a photograph by Karsh of Ottawa. It seemed a reasonable ambition, not because anyone had yet suspected that I could write, but because I enjoyed a secret intimacy with authors, all authors, that was conspicuously lacking from my relations with any other human beings. They might not know it yet, but I was one of them; and this perverse conviction was the tranquillising drug on which I dosed myself, several times a day, through ten years of childhood and adolescence.

Outside these daydreams of literary celebrity, I cut a fairly sorry figure. It was the old, too-often-written story of the ‘delicate child’, packed off at eleven to a school of daunting military and athletic traditions, where milksops were not suffered gladly. Fusewire-thin from several years of a wasting disease called coeliac, the boy wheezed when he moved, and sounded as if he’d trapped a flight of herring gulls inside his chest: he was no asset as anyone’s friend. So (and this is how the story always goes) the child made friends with books instead.

Books admitted me to their world open-handedly, as people, for the most part, did not. The life I lived in books was one of ease and freedom, worldly wisdom, glitter, dash and style. I loved its intimacy, too – the way in which I could expose to books all the private feelings that I had to shield from the frosty and contemptuous outside world. In books you could hope beyond hope, be heartbroken, love, pity, admire, even cry, all without shame.

No author ever despised me. They made me welcome in their books, never joked about my asthma and generally behaved as if I was the best company in the world. For this I worshipped them. I read and read and read – under the bedclothes with an illegal torch, surreptitiously in lessons with an open book on my knees, through long cathedral sermons, prep, and on the muddy touchlines (‘Kill him, Owen!’) of rugby pitches, to which I was drafted as a supporter. I did not then see any logical hiatus in the proposition that since I was happy only when I was with authors, I must therefore by definition be an author myself.

I had long ago discovered the trick of switching the world off like a light and entering fictions of my own. First, you had to let the room full of boys drift out of focus and wait for their voices to dissolve into a blur of white noise. Then – Jim turned on his heel. The smoke from the cigarette in his ivory holder rose in slow coils. ‘Let’s go,’ he said, picking his way, agile as a mountain buck, through the huge boulders of the tinder-dry watercourse … Jim was my heroic alter ego. His chronicles were never written, but they lay in my head as accessible and as palpable as memories. He began as the natural leader of a band of men called The Marines, whom he conducted round the world on adventures that were a distillation of all the best bits of Buchan, Edgar Wallace, W. W. Jacobs and Conan Doyle. Jim, who was sometimes called The Captain, smoked a lot, drank Green Chartreuse, solved crimes, found things for people, did a great deal of camping out, spent whole days fishing, and every so often led his men off to wars fought with épées and sabres.

The story was continuous and I could slip into it at will, anywhere. Jim lasted me for several years; he had as much stamina as a character in Anthony Powell’s Music of Time. Like Widmerpool, Jim altered with the years. When I was thirteen he hung up his sword, changed his tipple to malt whisky and fell head over heels for a girl called Clarissa, whom he rescued from burning houses, runaway stallions, a cad with a Bentley and a Chinaman in the white slave trade. Clarissa was a clinging, lissom, wispy girl who cried easily. She and Jim went in for bouts of tender kissing but never, as I remember, got beyond Number Three.

But I grew ashamed of him. It was painful to see so transparently through the artifice of one’s own fiction and recognise the facts it was meant to palliate and disguise; and I began to suffer from daydreamer’s block. I hit on a more naked and modern form of autobiographical fiction. The new trick was to turn whatever was happening in the present into the past tense and the third person. Walking from School House to the library building, I thought: He walked to the library. A cold smile played round his lips. The avenue of trees, heavy and dusty with summer, closed round his head. He was thinking of death. This sort of thing could go on for hours at a time, an epic plotless melodrama into which I absentmindedly withdrew and from which I sometimes needed to be roused by brute force.

I suppose it happens to almost everyone, or at least to almost every adolescent, this urge to constantly rewrite one’s experience in terms more glamorous and significant than those in which it’s actually happening. But when the urge is hopelessly muddled up with dreams of authorship, and one hears the words falling in one’s skull in complete, plagiarised sentences, the symptoms of scribendi cacoethes are probably incurable.

In any case, I was now on a serious training scheme for authorship. I sent away to all the postal schools whose ads claimed that your pen could pay for your holiday. From the Regent College of Successful Writing I got a free copy of a booklet called 101 Infallible Plot Situations. The situations weren’t much in themselves. They went something like:

17. X contrives system of perfect murder. Confides it to Y. Y puts it into practice, but knows that X alone will know he’s guilty.

18. Girl’s dog goes missing. Found by stranger. Subsequent relationship between girl and stranger.

19. Eccentric conditions of wills.

20. Tribulations of lovers from widely differing social backgrounds. Resolution of same by third party.

As the introduction explained, all hundred and one situations were everyday occurrences, not plots in themselves. Yet when you combined three (or, if you were suitably experienced, even more), you had a unique plot, never before used by any of the world’s top novelists and masters of the short story, involving dog, girl, stranger, perfect murder, eccentric will, class conflict and third party, with fire and theft to boot. With 101 Infallible Plot Situations, you could evolve narratives of such dazzling originality that in half an hour the merest tyro could out-Dickens Dickens.

I kept a notebook of plots. I also bought a little orange monthly magazine called The Writer, whose articles were calculated to flatter and feed the ambitions of fourteen-year-old authors. There were articles about how to write a successful Letter to the Editor, about how to choose your nom-de-plume (Nosmo King was thought a particularly apt and witty example), about margins, spacing, return postage and the absolute necessity of the twist-dénouement. The contributors all affected an airy sophistication about their trade that I found toxic (‘Writing the short short story, I prefer to take one bite at the cherry, at most two …’).

I was almost there. I had a stock of plots, I knew how to lay out the title page of a manuscript, I knew it was pure folly to try using foolscap paper (always stick to quarto), I knew about swift, vivid characterisation, how to cut down on description and when to introduce the Surprise Revelation. The profession of authorship lay wide open, and beyond the doors stood Karsh of Ottawa ready with his camera. I could see my stories already printed in Lilliput, Men Only, Wide World, Tit-Bits and all the other ‘outlets’, as I’d learned to call them, where the literature of the twentieth century was being forged.

It took a little while to discover that I’d fallen for a sad, shabby, subliterate version both of writing and of being a writer. It was shattered, and not before time, by the experience of reading. Drawn to the book by its title (I’d never heard of its author), I read Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. I hadn’t realised. I’d thought that novels were cleverly contrived escapes from the world, and that writing them must be something a bit like fretwork. Portrait of the Artist made the reader live in its language, and made him live more arduously, more unhappily, more intelligently in the book than he had ever lived in the world. It made some obscure but fundamental change to the essential grammar of things. I read it with excitement and shock, three times over in quick succession, dazed to find myself simultaneously so deep in a book and so deep in the world. Every work of literature turns the successful collaborative reader of it into its co-author. In an important sense, we write what we read. My Portrait of the Artist defined my brimstone relations with my father and my family, with my boarding school and with my shamed sense of sexuality. Reading it, I stole it from Joyce and wrote it for myself; and as I went on reading I saw that if this was writing, it disenfranchised every book I’d read up to this moment. It turned The Writer and 101 Infallible Plot Situations into facetious piffle.

That sense of literature as an astounding private discovery is hard to bring back without sounding either superior or over-flushed with romance. The books themselves now have the ring of items on a syllabus: Joyce, Hemingway’s short stories, Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye, Iris Murdoch’s Under the Net … nothing much that is out of the way there, yet in 1958 each one happened for me like an accident on a wet road, sending the world into a spin.

I was academically backward, and a more sophisticated sixteen-year-old would probably have taken these novels more casually in his stride. But the boys I was at school with were not sophisticated either: they went in for Motor Sport, Leslie Charteris and Hank Janson, and thought that Hemingway’s In Our Time was lousy value as a swap. We did our Goon Show imitations, listened to Radio Luxembourg, the Station of the Stars, and tried to set light to each other’s farts. It was not like Cyril Connolly’s Eton at all.

I left the school with a handful of mediocre O-levels and was transferred to the sixth form of a very civilised co-educational grammar school, where the girls read D. H. Lawrence and the boys read John Betjeman and Evelyn Waugh. Hadn’t I read Scoop? Women in Love? Black Mischief? The Waste Land? Summoned by Bells? Actually, no. It took me at least a fortnight of whirlwinding round between the Lymington public library and the vicarage just outside the town to catch up with the literary circle in which I now moved. My target was to gut ten books a week – one a day from Mondays to Fridays, and five in the course of each weekend. I was paying little more attention to my formal lessons than I had done at boarding school, but I was reading Eliot, Beckett, Pound, Lawrence, Amis’s Lucky Jim, Wain’s Hurry on Down, Olivia Manning, Sartre’s La Nausée, Kerouac’s On the Road, Ginsberg’s Howl, all of Christopher Isherwood, Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, Anouilh, O’Neill, John Osborne, Wodehouse, Waugh. Racing through to catch the flavour, I worked like a reviewer with a deadline.

I’d found serious competition. Iris, who sat across the aisle from me in English classes, was also going to be a writer. In the second week of term she announced in a deep, actressy voice that she wanted nothing to do with babies and that it was woman’s higher calling to give birth to books. I was torn between craven infatuation and affronted pride. Like Hitler and Mussolini settling their differences over the Austrian border, Iris and I became allies, then friends.

Iris was a Lawrentian. She’d discovered Women in Love in the same spirit as I’d come across Portrait of the Artist. She organised Lawrentian walks through the New Forest, where she opened her arms to the sun and sighed as if she was coming to a slow climax. She challenged me to roll with her in wet grass, not for the usual reasons, but so that we could both experience a mystical communion with the earth. When I made the mistake of trying to put my arms round her, Iris reminded me, a shade coolly, that not only was she a Lawrentian, she was a Platonist as well. I thought this disingenuous: it was well known that Iris was up to something unplatonic with a bus conductor called Jim – my own lost doppelgänger. She sometimes told me about the muscles on Jim’s back and his strong thighs as if she was describing a landscape that she’d seen in Scotland or the Lake District. Jim was her Mellors – a legitimate object of physical passion because it said so in the book. I was afraid that Iris saw in me a convenient stand-in for Clifford Chatterley.

In 1959 the magazine John O’London’s Weekly announced a short story competition for young writers aged between sixteen and twenty-three. Iris and I both rather despised John O’London’s; it was middlebrow and suburban, new words of abuse for both of us. It went in for cosy chat about authors (how Caryl Brahms couldn’t bear to face the day without first brushing her teeth with a certain brand of toothpaste), neo-Georgian poems, well-turned Coppardian stories and kid-glove reviews. Yet even Iris admitted that publication in John O’London’s (with a suitably large photograph) would constitute a recognisable ‘start’.

‘If I win the first prize and you win the second …’ she said generously.

For a month Iris worked on her story in secret, occasionally giving out hints as to what it was about. It was ‘tonal’. It was to be dominated by images of darkness and blood. Blood and the moon, didn’t I see? I did, and guessed that Iris’s masterpiece was going to be way over the heads of the people at John O’London’s. Then I heard that she was having to cut it down, because it had turned into a novel.

My own effort was written between lunch and suppertime up in my room in the vicarage, and was posted off to John O’London’s the next morning, without revision. I didn’t admit to Iris that I’d written it. I knew that if I did, she’d plague me about the ‘images’ in it, and I’d have to invent all sorts of symbols and ironies in the piece that I knew were not there.

When, three months later, it was announced that my story had won joint first prize in the competition, I was first thrilled, then embarrassed. On publication (for which I got eleven guineas and a scholarship to the Writers Summer School at Swanwick), ‘Demobbed’ was posted up on the school noticeboard among the football and hockey results. The headmaster’s praise at school prayers was fine, but I was alarmed about Iris and the intelligentsia of the sixth form – for the story was culpably innocent of all my adventuring among the classics of modernism. It read like a story written by someone addicted to The Writer, 101 Infallible Plot Situations and John O’London’s Weekly.

I had wandered in the garden, among the marigolds and around the tall, sour-smelling hollyhocks. The flowering cherry flung gaunt arms towards me, while at the bottom of the fence the stone toad glared at my fingers as they explored the grain of the creosoted wood. The great grey bird bath erupted from a patch of grass and stood like the pillar of a desert temple. I could reach its gritty top and see my face in the hollow of green water …

‘Well,’ Iris said, ‘I suppose that’s what they would have wanted, isn’t it?’

Had a course in English Literature at university not been a few months away, ‘Demobbed’ might, as Iris put it, have been a start. It wasn’t, though it did prove that the seventeen-year-old could now manage what he’d been dying to do three years before. So maybe in three years’ time …

Iris went to Oxford. I went to Hull (the only university in England which then accepted candidates for an honours degree in English without requiring a GCE pass in Latin), and found there a more elevated literary vocation than that of authorship. Authors were inspired innocents, barely conscious of their real intentions, half-witting creators of texts whose ultimate glory lay in their transfiguration by the critic. Just as my head had been turned at sixteen by Portrait of the Artist, at eighteen it was almost wrenched clean off my shoulders by William Empson’s Seven Types of Ambiguity. In my first term at Hull, I heard someone in his final year say that Seven Types was the most famously difficult book in the pantheon. I bought it that afternoon, and went through a course of instruction with Empson that closely resembled the process of conversion at the hands of Ronald Knox or Father D’Arcy. It was tough. I read, and thought I understood, then thought I didn’t. The revelation that Shakespeare’s ‘bare ruined choirs, where late the sweet birds sang’ was alluding importantly to the dissolution of the monasteries (and its brutal recency, at the time when Shakespeare was writing), to the homoerotic charm of choirboys, and to much, much else, made me realise, for a second time, that I’d never really read a book before.

Empson’s dizzying ambiguities were phrased in a language of exuberant common sense, of as-any-chump-can-see. He didn’t stand on ceremony, was interested in all kinds of distinctions of writing, from poems in Punch, newspaper headlines and 1930s proletarian novels to Chaucer and Spenser and Shakespeare. He was impertinently funny. After a chapter devoted to the deep reading of Shakespearian puns, Empson could remark:

It shows lack of decision and will-power, a feminine pleasure in yielding to the mesmerism of language, in getting one’s way, if at all, by deceit and flattery, for a poet to be so fearfully susceptible to puns. Many of us could wish the Bard had been more manly in his literary habits, and I am afraid the Sitwells are just as bad.

Empson’s taste in literature was wonderfully broad, and there wasn’t a milligram of cant in his writing.

The dominant tone of the English department at Hull was palely Leavisite, and the leader of the movement was always referred to in lectures as ‘Doctor Leavis’ as if he was the visiting consultant surgeon, a specialist in amputations, at the cottage hospital. ‘As Dr Leavis observes …’ was a favourite tag of C. B. Cox, Hull’s most notable critic in residence and co-editor of the Critical Quarterly. I took against Leavis. His voice came clearly through his books, The Great Tradition and Revaluations in English Poetry, and it was a narrow, rancorous voice – a voice that I recognised as belonging to the moralising evangelists from whom I was on the lam. Where Empson was a nobones atheist, Leavis’s books had the smell of the chapel on them. He was obsessed with false gods, like Swift, like Dickens (dismissed as a mere entertainer). His authorised canon of masterpieces were books that were good for you, or, in Leavis’s phrase, ‘culturally sanative’. I had enjoyed reading Conrad and Lawrence until I read Leavis extolling them for their powers of cultural sanativeness, when their work suddenly seemed to go stale under the weight of Leavis’s praise.

The more I read of Leavis, the more I hero-worshipped Empson for his playfulness, his generosity, his extraordinary cleverness, his literary hedonism. If I imagined Leavis taking a book down from a shelf, I saw a man either reverently handling a gospel or fastidiously rejecting a heretical tract. If I imagined Empson doing the same thing, I saw him carting it off to a comfortable chair for an hour or two of delight. Empson would laugh aloud. You couldn’t ever imagine Leavis laughing. Leavis would read what you had just read, and castigate you for your bad taste in liking it. Empson would read what you had just read, and read it twenty times better, finding jokes you’d never seen, sly allusions that you’d missed, richnesses and contradictions that made you want to kick yourself for having skimmed too fast over. He wasn’t ‘difficult’ at all, I discovered. He just took his reading more slowly, and relished it in more detail, than any other critic.

When I sat down to write my fortnightly essay, I asked myself, ‘What would Empson see in this?’, and turned in pages of earnest Empson-pastiche, complete with attempts at Empson’s inimitable style of slangy, low-falutin, this is the line to try on the dog talk. In photographs of that time, Empson always appeared in a straggling Fu Manchu moustache, with flying sidewhiskers; for three weeks I tried to cultivate something similar, but all I managed to grow was an unappealing crop of pubic down.

In the early and middling 1960s, there was a lot of higher education about. The new universities were being built at Sussex, Essex, Warwick, East Anglia, Lancaster and York. Kingsley Amis (then a lecturer at Cambridge) announced his political apostasy with the slogan More Means Worse. More certainly meant people like me. The drift from being a student to research to an appointment as a university lecturer was an easy one, even if one started from an unfashionable place like Hull. I joined the drift. In my last year as an undergraduate I’d been reading the novels of Henry Roth, Nathanael West, Malamud, Bellow and the young Philip Roth, and thought I’d found in them a suitably grave doctoral topic with a solemn-sounding title to match. Variations on the Theme of Immigration and Assimilation in the Jewish American Novel from 1870 to the Present Day. In fact this ugly threat of a title was only a cover, designed to throw the professors off my scent. I saw it as licensing a three-year wallow in the most exciting contemporary fiction that was being written in English. Saul Bellow had just published Herzog, a book so redolent of its period, so lavish in its style, so rich in metaphor (and irony, and ambiguity, and wit), that it seemed as if the English novel in the late twentieth century had at last found its masterpiece; a work to set beside Dickens’s Our Mutual Friend or James’s Portrait of a Lady without feeling that the art of fiction had seriously diminished since its great Victorian maturity. To spend whole weeks reading Bellow, and to try to read him with the alertness and the subtlety of Empson, seemed an improbably lucky fate, and I was paid four hundred and fifty pounds a year for keeping the best possible company in the living literary world.

By 1965, the drift had quickened to the speed of an avalanche. The advertisement pages at the back of the New Statesman were clogged with Academic Appointments, and almost anyone with a good honours degree and a reasonably plausible line in academic talk could land a salaried job as an assistant lecturer at one thousand and fifty pounds a year. The University College of Wales at Aberystwyth employed me to teach English and American Literature at their converted railway hotel, a magnificent piece of high gothic that fortuitously resembled an inferior Oxford college. Though the flood of job advertisements might have suggested that our services were urgently needed, and that we’d be worked flat out, the actual duties involved were still gentlemanly and donnish – seven or eight teaching hours a week, with an ocean of leftover time in which to read and write.

I scrapped my thesis and wrote a textbook called The Technique of Modern Fiction, which was based on the ‘practical criticism’ classes that I was taking with first-year students. It should probably have been called something like The Technique of Chatting about Fiction in First-Year Seminars, but it was accepted, with a fifty-pound advance, by Edward Arnold, the educational publishers, who went on to commission a twenty-two-thousand-word essay on Huckleberry Finn (one hundred pounds more) for their ‘Studies in English Literature’ series. Between books, I wrote a handful of articles with footnotes for journals that paid with parcels of offprints.

For someone in love with the idea of writing, the joy of writing something hasty, derivative and bad goes as deep as the joy of writing something genuinely original. The play of the words on the page, the illusion of forming a fresh pattern, crisply phrased, the heady sense of having nailed a fragment of the world with a telling metaphor, come more easily, if anything, to the bad writer than to the good one. Sitting at the kitchen table in the first-floor rented flat in Moreb (Welsh for Sea-View, though the sea was obscured by a bingo hall) on Bath Street in Aberystwyth, I was intently happy as I tapped away at very threadbare sentences. It was what I had daydreamed of doing for as long as I could remember. When the first galley proofs arrived, they gave off a faint whiff of old clothes, as if the rags from which their paper had been manufactured had been stripped from the backs of tramps. It was the authentic smell of writing as a trade, a trade secret. So was the page of proofreaders’ marks that I sellotaped to the wall – columns of arcane squiggles and cross-hatchings and underlinings and code letters. I enjoyed the daily wrangles in the classroom with my students, who were so nearly my own age that it was like arguing about books with a ready-made party of friends, but they couldn’t compare with the glamorous musk of the writing stuff on the kitchen table and its promise of another, riskier career.

After five terms of teaching at Aberystwyth I applied for a lectureship at the University of East Anglia. The novelist Malcolm Bradbury held a senior lectureship in American literature there, and I was appointed as his junior. Angus Wilson also had a part-time chair at Norwich, teaching in the summer term and starring at parties during the rest of the year. Wilson gave the university a generously disproportionate amount of his time. He was its Public Orator, he entertained students and staff at elaborate, lantern-lit evenings in the garden of his Suffolk cottage, he was a continuous waterfall of talk – about literature, writers and the business of writing. Between them, Wilson and Bradbury kept the students, at least, reminded that there was a fundamental marital relationship, however tricky, however punctuated by resentful arguments and riddled with mutual incomprehension, between the activity of writing and academic reading and criticism. Wanting to write – and wanting to write something looser than the strangulated exercises in lit. crit. that I’d managed so far – was made into a perfectly ordinary and reasonable ambition by their presence. During the time that I was at East Anglia, Bradbury and Wilson’s students included Rose Tremain, Clive Sinclair, Ian McEwan and the playwright Snoo Wilson; the university was, unusually among universities, a place that had a place for writers, whether they were teachers or students.

I saw the university as a springboard from which to dive into Grub Street. London was one hundred minutes away by train, an inky city of editors, publishers, agents and producers. It was where writers lived – the city where you would write, if only you could live there.

Working in vacations in an attic room in Norwich, I wrote fast and sloppily, trying to gain a ticket of entrance to the city at the far end of the line. A long play for television, set on the campus of a university somewhere in the north of England where the smell of the fishdocks got into the lecture theatres. An interval talk for Radio 3 about Browning and Pound (accepted and broadcast, thirty pounds). Another, about Jewish American novels (ditto). An unkind piece of reportage about the filming of a political TV programme at the University of East Anglia which had ended prematurely in a small riot (New Society, fifteen pounds, and an angry wigging from the Professor of Fine Arts). Another New Society piece about fruit machines in pubs. A book review (about nineteenth-century poetry) for the New Statesman. A piece, which wasn’t exactly a short story, or a slice of autobiography, or a satire, about the sort of people I’d been meeting on the New Left. A short story, in thrall to the early stories of Angus Wilson, about a modish lecturer at a new university, rather too full of the brand names of the moment.

Malcolm Bradbury and I had talked of the difficulty of freelancing for a living, and he’d used the word ‘diversification’. It was like working in any other industry, he said; you had to learn to diversify, cutting and running from fiction to journalism, broadcasting to print. I took him more literally than I think he had intended, and tried to set myself up on so many fronts that I deserved to fail on every one of them.

I sent the television play to Curtis Brown, the agency which handled Bradbury’s work. The TV man there, Stephen Durbridge, read it, asked me to lunch (the lunch alone would actually have been enough to sustain my fantasy life for several months), and sent the script to a producer who said it was unproducible but liked it enough to commission another play from me, for five hundred pounds, nearly a third of my annual salary as a lecturer.

A radio producer, Russell Harty, who’d listened to the talks on Radio 3, invited me to join the weekly programme ‘The World of Books’ as a regular contributor. One programme a month, eighteen pounds a programme.

Anthony Thwaite, the literary editor of the New Statesman, wrote to say that there was a space on the ‘fiction roster’ – another monthly job (twenty-five pounds a throw), which involved sifting through all the novels published in a particular week and choosing three or four of them for review. The books (and there were often more than twenty of them) would remain the property of the reviewer, and he could sell them at half price to the library supplier, or knacker’s yard, off Chancery Lane. This turned the original twenty-five pounds into something nearer fifty pounds.

I sent the stories – or, rather, the story that wasn’t and the story that was – to Alan Ross, the editor of the London Magazine, enclosing a quarto stamped addressed envelope. Ten days later, I spotted the magazine’s printed letterhead on a much smaller envelope and knew, with a whoop of relief, that Ross hadn’t sent me a rejection slip.

A SENIOR LECTURESHIP

Anthony Freeman’s first marriage had ended somewhere around the back of Baker Street, in the consulting room of a psychoanalyst who had something to do with the Tavistock Clinic. On the third joint visit he’d come back alone to the Volkswagen, just in time to watch the Excess Charge plate click into place on the parking meter. Two months later he took up a temporary lectureship at the University of St Andrews, where he ‘recovered’. He dined out a good deal (‘We must have Anthony round; introduce him to Agnes/Fiona/poor Mrs Taggart’), took to birdwatching with a huge, military-looking pair of Zeiss binoculars, and wrote four drafts of an article on Chartism for the English Historical Association Bulletin. He wore his divorce like a campaign ribbon. The psychoanalyst became a major character in his rather good after-dinner stories: ‘Curious chap, actually. Jewish, of course. Had a chest-expander on his desk …’ He swapped the Volkswagen for an MG and took a quite pretty PhD student on a walking tour of the Highlands.

Two universities later he was splendidly remarried. At Leeds he slept with a beautiful third-year girl in his Foreign Policy course. She had a chiselled face and body that looked as if they’d been assembled by a master craftsman from the best available materials. She had all the Rolling Stones records and occasionally smoked pot for social reasons, but she was perfectly adapted to Vice-Chancellorial dinners and everyone thought Julia was marvellously right for Anthony. In the past, lecturer–student affairs had been subjects of scandal and concern, but this one was in a class apart. Julia would have been incapable of anything vulgar. Anthony was such a young thirty-eight, and Julia would be so good for him. She became a favourite of professors’ wives, the expert on hemlines and pop and interior decoration. She bought David Levine ceramics and the latest Liberty prints; she made the Pink Floyd sound wholesome and taught the wife of the Professor of Constitutional History to say things were ‘draggy’ or ‘super’. Anthony changed the MG for a Rover 2000 and was offered a senior lectureship at the University of Warwick. In the summer vacation after Julia’s graduation (she got an average upper second; Anthony had a ‘good’ one), they were married.

For their first year at Warwick, things were perfect. Their life looked like the product of some extremely sophisticated piece of electrical circuitry. The Great Programmer had done a fine job with Julia’s beauty and Anthony’s after-dinner stories. ‘There’s rather a good one going round about LBJ,’ Anthony would say, and Julia’s exquisite face would signal, this is a super story, you must listen to this, like a puppet on Thunderbirds. Each of them expressed their opinions with the marital ‘we’. ‘We don’t really care for Godard, he is rather overrated’; ‘We rather liked that book by Marcuse, what’s its name?’; ‘We thought the David Mercer play was absolutely super …’ When someone brought up a new film, one would ask the other, ‘Did we see that, darling?’ Then they would glaze simultaneously and the nervous junior lecturer (curiously he always was junior to Anthony) would be left awkwardly sketching the plot. Somebody once suggested that they both must have had an identical, vital part of their brains removed by surgery in their infancies. But that was not in the professorial circle, where they were oddly popular.

When they entertained Anthony’s junior colleagues, the evenings tended to dissolve into unrecognised disaster. With Assistant Lecturers, they developed a technique for encouraging intimacy by sitting intertwined on their sofa. Julia would nuzzle Anthony and stroke the neat fur on the back of his neck, while Anthony, with his arm around her, was saying things like, ‘I think that’s only one side of the story. You see, the Vietnamese …’ or ‘We thought it was rather a good novel. The plot and the dialogue —’. The Assistant Lecturers would meet in one another’s offices and rehearse favourite well-worn scenes from the private life of the Freemans over coffee or beer. The couple were made to lie in bed tenderly grappling with one another like delicate, copulative robots, and discuss the merits of Ayn Rand, Leon Uris, the Wolverhampton Problem and Marshall McLuhan, arriving at their perfectly timed climax with an ecstatic ‘We think – we think – we think!’

But the jokes wore thin and gave way to new fictions. It was decided – quite why nobody knew – that Julia was more ‘intelligent’ than Anthony, that she was bored with robot sex and robot intellectuality in their pastel coloured period house. If she was bored, perhaps she was seducible. She could turn on, have an affair, storm into Anthony’s office, crash the Rover, take an overdose, cover the floor and walls of the drawing-room with scraps of paper, notes, newspaper cuttings. She could be found alone in pubs in the early evening, develop a bronchitic cough, take courses in sociology, disappear for days to London. But nothing. She failed to transmit signals of any kind. At half-past five every evening she collected Anthony from the university. She moved into the passenger seat; they kissed through the window; Anthony moved round the front of the car, sat in the driving seat. Pause. Kiss. Anthony drove off. Every bloody evening.

Then she got pregnant. Or rather, ‘Julia is – ah – having a baby.’ In Anthony’s terms, only neurotic, undisciplined, unmarried students got pregnant. Anthony bought Doctor Spock in the university bookshop and the professorial wives closed round Julia in a tight knot of coffee mornings and communal trips to the baby boutique. Julia made a tiny dent in the offside wing of the Rover after taking a corner on the campus (limit twenty m.p.h.) at thirty-five. The Assistant Lecturers put this down, in their ignorance, to her pregnancy. The following week, Anthony drove himself in and out of the university, and Julia stayed deep in among the pastel colours, listening to the gurgle of the central heating, or playing the Fugs records that a friend had brought back that summer from the States. From the outside you might have forgotten she existed, if it hadn’t been for the sudden and incongruous blooming of Anthony.

It started with a leather jacket. He’d always gone around in lightweight summer suits before, and the glistening new leather made him look like some sort of hatching chrysalis. Almost immediately he started the beard. It grew in scattered patches of fuzz, as if unwilling to take root on the unlikely surface of that smooth face. An Assistant Lecturer found some excuse to visit the pastel Freeman house one evening. ‘Don’t you think Anthony will look super in a beard?’ Julia had said over the top of a Fugs record. ‘We decided he ought to grow one.’

‘Very nice,’ said the Assistant Lecturer, marvelling at the extraordinary effect of Julia’s very unpregnant two-months-gone body in a maternity smock.

‘It’ll have to grow before the VC’s Thanksgiving Day party,’ said Anthony, ‘otherwise it’ll have to come off.’

Julia picked up Doctor Spock and held Anthony’s hand as she read.

The beard grew, first lame and untidy, then darkening into a magnificent fierce wedge. Anthony arrived one morning to take a tutorial in a fez. ‘Going abroad?’ someone inquired at the door of his office. Anthony shrugged uncomprehendingly and walked on. His ties widened to kipper width; the collars of his shirts began to grow down his chest. His trousers, like creatures participating in an evolutionary cycle, first narrowed, then swelled and flared around and over his new yellow moccasins. His vocabulary took a sudden uncertain lurch towards the West Coast; at a department meeting Anthony remarked that the preliminary examination results were ‘a pretty rough sort of scene’. Someone sniggered and asked, sotto voce, for a translation.

In the fourth month of Julia’s pregnancy Anthony exchanged the Rover for a Renault 4L. They gave a party, sending out invitations under plain Anthony and Julia, and leaving out the Freeman. These invitations came, not on deckle-edge cards as before, but on slips of duplicating paper, processed by the department secretaries in the lunch hour. For the first time the pastel house was opened to students, a promiscuous research assistant, and a huge fat man who was believed to write for International Times. All these besides the cadaverous professors and their wives, the business neighbours, and the junior faculty arriving in their beat-up Minis. ‘Hi,’ said Anthony to each new guest, while Julia stood placidly behind him, all inwardness and maternity wear.

‘I think Julia’s already had her baby,’ said an Assistant Lecturer, looking at the unused spaces of Julia’s smock as she stood beside the resplendent Anthony. In fact all the clichés about fulfilled motherhood seemed true of Julia then; it was hard to imagine how a real child could possibly compete with the brand new Anthony in his flared trousers and lace fronted shirt.

‘Let’s get high,’ Anthony said at large. He was carrying a gallon jar of cheap burgundy.

‘Got any beer?’ said the professor of Medieval History who was president of the Wine Committee.

‘Is that the Beatles, dear?’ his wife asked Julia, by the stereo equipment.

‘No, the Fugs.’

‘Oh, how nice,’ said the professor’s wife doubtfully.

Someone from the group of students asked Anthony if he wanted to smoke, and Anthony said to wait till later, but was evidently flattered to be asked. The man who wrote for International Times was talking about R. D. Laing who he called Ronnie, and a girl was sick in the downstairs lavatory. The professorial circle established itself in the dining-room, all apart from a sociologist who’d once been on Late Night Line-Up and was under the impression that it was a student party anyway. Anthony got a research student to help him roll up the carpet.

‘I’ve never actually seen a carpet rolled up before,’ said the student. ‘I thought it was just an expression.’

Anthony shrugged, and tucked an exposed tail of his lace fronted shirt into the waistband of his hipsters.

The professors took their wives away early. Anthony and Julia stood at the front door while the wives gazed at Julia and glanced puzzledly at Anthony.

‘Thank you so much, dear,’ they said to her. ‘You must come round for coffee again this week.’

In the cars with their husbands, the wives said, ‘I do want to see Julia by herself. I’m quite worried about her. Anthony is so strange nowadays … those dreadful clothes —’

‘I expect it’s just a phase,’ said the professors, changing gear. Pregnancy was such an odd affair anyway; some men sat it out in the Senior Common Room bar, or took to visiting the flats of their girl students. Leather jackets and flared trousers seemed, by comparison, quite a harmless survival strategy. And that shirt rather suited him, really.

The students sat around like rabbits on the bare floor of the Freemans’ drawing-room drinking beer out of cans. Four of them passed a cigarette from hand to hand and stared, preoccupied, at the dusty floorboards. Julia reigned above them, curled into a corner of the sofa, as an earnest fragile boy talked to her about babies. Anthony’s shirt rippled uneasily above his waistband. ‘Ah … yes … ah … rather … yes … ah,’ he said teetering from one foot to the other. ‘Like the … ah … whole political history scene is … ah … kind of shaking up —’

In the pale mauve hall the fat man who wrote for IT had found a tiny student in a white dress and was feeding her with whisky from a flask. ‘Man,’ he said, ‘what a bloody zombie. Did you see those books in there? It’s the first time I ever met someone who had the complete works of Herman Wouk.’

‘I did a history seminar with him once,’ said the student. There was a long pause. The man tugged at the tufts of the thick pile carpet. ‘It was rather boring,’ she said.

In the week after the party Anthony cancelled his survey lectures because, as he explained, lectures were non-participatory. Instead, he parcelled out ‘projects’ – the theme of Betrayal in psychology and history, the theory of Apocalypse, the Charismatic Leader. He shelved his old PhD thesis which he’d been turning into a book for the last eight years because, he said, like it wasn’t the sort of history that mattered; like, it wasn’t Relevant. The students though, unsurprisable, put up with his Projects as they’d put up with his lectures. They took incomprehensible notes; their pens ran out of ink; they stared out of the window of his room at the neat university lake with its expensive collection of eider ducks. Anthony would lean forward and raise his hand like a priest. ‘Like, ah … John Cage …’ he would say, blinking at the girl who fingered her indian beads.

In the sixth month of Julia’s pregnancy he slept with a third-year student. This was, in fact, rumoured long before it happened. Anne was taking his modern politics course in the irregular intervals between experimenting with hand-held shots of the campus with a baby Bolex. ‘Like, all this academic work is, like, categories,’ she said. ‘Like it’s all mixed media kind of things now.’ She recognised Anthony’s new life as a miraculous conversion, and began to gaze at him during seminars with pot distended pupils. For her class essay she handed in a poem (a Black Mountain collage of places, dates, fragments of news and vague intimacies). Anthony gave it a β–. Anne whipped out her Bolex and snapped him in his office. ‘Picture of a fink,’ she said. Anthony slept with her that afternoon in the double bed in her untidy flatlet with damp patches on the ceiling. Julia waited for him for fifteen minutes in the Renault; went to his room, found it was locked, drove home, and started a ragout from Elizabeth David.

No one was certain if Julia knew. Perhaps she’d planned it this way. Perhaps Anthony described every detail to her, starting with the scene in the pub when Anne kicked off her shoes and wiggled her toes in front of Anthony’s astonished face. He’d coughed, grinned, and gone on drinking beer. At any rate Julia grew, if anything, even more placid. She sat (reported the Assistant Lecturers) at the plain deal kitchen table surrounded by books on baby care. Chills … Colds … Colic … Colitis … Croup … Cuddling. Methodically, like a student revising for finals, she plodded alphabetically through every infant ailment known to Spock. She practised folding nappies and stood in front of the bedroom mirror with her arms cupped around an imaginary child. For an hour each day she stretched and swung and bent her body until it was supply ready to spring forth her baby like an oiled trap.

Anthony, though, woke with beery headaches and pains in his abdomen. He muttered in his sleep (Julia would slowly run her forefinger down his spine and he would quieten), and started ordering newspapers which he spread round the drawing-room floor, reading into the small hours. ‘Do you think it’s good for your eyes, darling?’ Julia asked. ‘I just read a poem,’ said Anthony. ‘There was this line in it, “We are all in the da-nang.” It sort of means – you know?’

‘Would you like some cocoa before we go to bed?’ said Julia.

Anthony crawled over the newspapers on the floor on hands and knees towards a day-old copy of the Morning Star. ‘No thanks,’ he said, hunting for the Foreign News page.

His seminars began to hum with words like ‘class’ and ‘justice’ and ‘control’. He prescribed Eldridge Cleaver as a set book and talked slowly, in a low sad voice, of revolution. In bed with Anne, he confessed. Holding his head in his hands he said, ‘Like, she’s so bloody … middle class.’ Anne narrowed her eyes, composing Anthony into a shot in an underground movie.

‘Leave her,’ she said.

‘I couldn’t … hurt her that much,’ said Anthony.

‘Well, that’s that then, isn’t it!’

Anthony looked round at her. ‘She’s so dependent on me … she’s almost like a child —’

Anne shrugged.

‘Anne, Anne …? Do you want me to stay with you?’

‘Okay – like, I don’t want to make you go one way or the other —’

‘You need someone to look after you. I’ll take care of you, Anne —’ Anthony said, sorrowfully.

He drove the Renault back to the pastel house, only just missing a milkvan in a sidestreet. Julia was doing her exercises. ‘Julia,’ said Anthony, ‘I’ve got to be honest – with you – and with myself.’ Julia straightened up slowly, rising on the balls of her feet. ‘I’ve just got one more exercise to do,’ she said. ‘For the tummy muscles.’

‘You’re so bloody middle class,’ Anthony said, tremulously.

‘There, that’s it,’ said Julia.

‘We’re not being honest with each other,’ said Anthony.

Like ballet dancers in rehearsal, they began to row.

At the beginning of the eighth month of Julia’s pregnancy she parked the Renault off Baker Street and spent two and a half hours with Anthony’s ex-psychoanalyst. When she returned to the car the Excess Charge sector showed on the meter. She fed another sixpence into the slot and sat tranquilly in the driving seat, touching the stretched skin of her stomach with wonder.

At the same time, Anthony lay stretched naked on the crumpled sheet of Anne’s enormous double bed. His beard flared around his mouth. He leaned over, touched the damp line of Anne’s stomach. Between them lay a copy of R. D. Laing, The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise. Anthony reached for his glasses from his trousers pocket, hung untidily over the back of a chair. He put on his spectacles and began to read.

1969

Ross added in his letter, ‘Are you interested in criticism? Do you want to review books for us?’ I gave in my notice to the dean of the School of English and American Studies, who told me I was probably doing the silliest thing in my life. He was twenty-five years older than I was and could remember a world where jobs were not so easily got nor so lightly thrown away. But in 1969 I’d had a six-month run of lucky flukes, and times were flush. The idea of living in London and writing for a living – writing anything for a living – possessed me completely. Every morning was distinctly brighter because of the idea. I had Larkin’s lines running in my head:

Ah, were I courageous enough to shout Stuff your pension!

But I know, all too well, that’s the stuff that dreams are made on …

But it’s not, and it wasn’t.

II

INFLATION AND DECIMALISATION have made 1969 prices look antique and the time more remote than it really is. A lecturer’s salary, with a handful of increments, was one thousand seven hundred and fifty pounds. A hardback novel cost from twenty-one to twenty-five shillings. To turn those figures into today’s values, one would have to multiply by a factor of between eight and ten.

In 1969 it was still – just – possible for a newcomer to scrape by on literary journalism, writing book reviews for the weeklies and for magazines like Encounter and the London Magazine at anything from fifteen to thirty pounds a piece. In 1987 terms, say one hundred and twenty-five to two hundred and fifty pounds. Taking part in arts and books programmes on the radio (another standby of the freelance) brought in very similar fees. Here are some actual comparisons from 1986/7 (three of them are mine, two are someone else’s):

Book review (1,000 words) for the Listener, £90; for The Times Literary Supplement, £75; for the Spectator, £70. For reviewing a book on the radio programme Kaleidoscope, £78.75. For appearing on a half-hour TV programme (Cover to Cover) and discussing four books, £125.

The rates haven’t kept up. Although some national newspapers like the Observer and the Sunday Times do pay their reviewers a good deal more than this (on a base-rate of about two hundred pounds a go), book reviewing has effectively ceased to be a means of serious subsistence. It may pay for itself, by a knifeblade margin, but it won’t buy time for other, more speculative literary work. You’d be so busy writing reviews that you wouldn’t have a spare minute in which to get on with a book.

It had not quite reached that stage in 1969. For seven pounds a week (or about three hundred words), I rented a large and comfortable room in a flat in Highgate and set up in business as a professional writer. The floor was littered with the jiffybags in which review copies arrived and with the wreckage of the commissioned play for television, which had stalled on me.

To write was still an intransitive verb. There was no story which insisted on being told – no object, except the act of writing itself. All the pleasure and interest lay in simply playing with words. Write! – but write what? If nothing else came to mind, you could write about not writing in a room in Highgate.

LIVING IN LONDON

The best place to commit suicide in north London is from the top of the Archway Bridge, a magnificently vulgar piece of Victorian ironwork that carries Hornsey Lane high over the top of Archway Road. Your death leap will cast you from the precarious gentility of N6 into the characterless squalor of N19. All Highgate trembles on the edge of that abyss, perched, like a gentlewoman of rapidly reducing means, above the ‘vapid plains’ of that ‘hot and sickly odour of the human race which makes up London’. Highgate was firmly behind the nineteenth-century rector of Hornsey, Canon Harvey, who declared (in a letter to The Times): ‘I have tried to keep Hornsey a village but circumstances have beaten me.’ It was always a place for prospects and dreams of the city lying below it: Dick Whittington turned again on Highgate Hill; Guy Fawkes’s cronies gathered in Parliament Hill Fields to watch the Houses of Parliament blaze. Then it became an escape hatch, as the middle classes built their purple brick villas like castles on the northern heights, in defence against the cholera and typhoid germs of William Booth’s Darkest London. N6 is an embattled vantage point; it overlooks the city with a chronic mixture of anticipation and fear.